Autofluorescence Profiling of Virgin Olive Oil: Impact of Rosemary and Basil Flavoring During Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Flavoring Procedure

2.2. Storage Conditions

2.3. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.4. Quality Parameters and Sensory Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Virgin Olive Oil Samples

3.2. Wavelength Selection for Autofluorescence Measurements

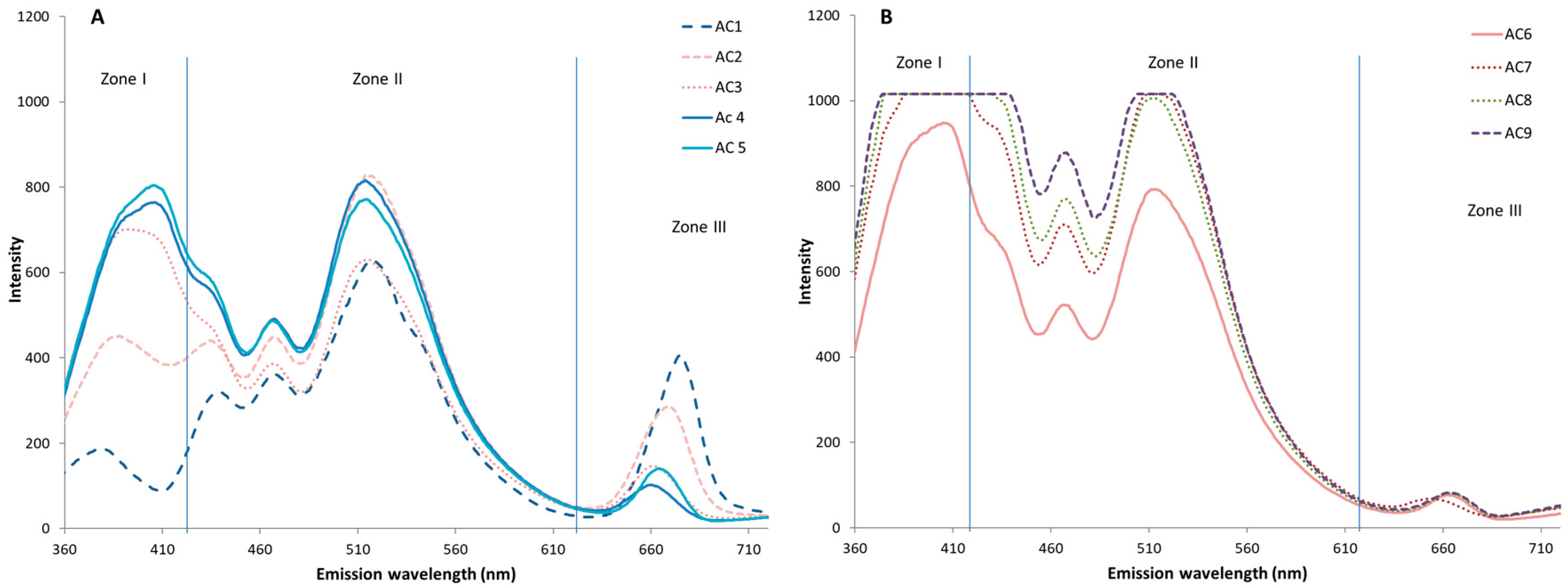

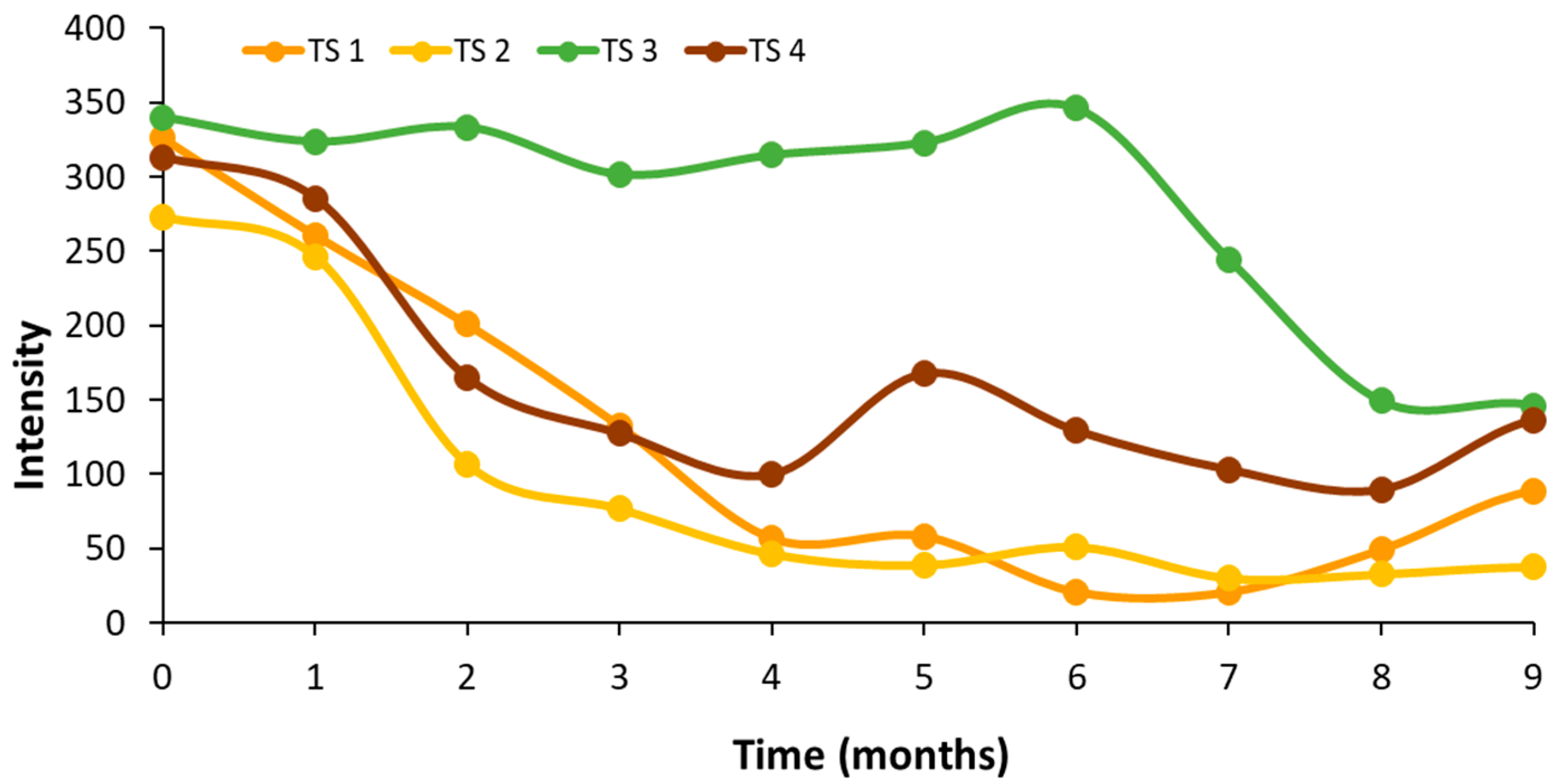

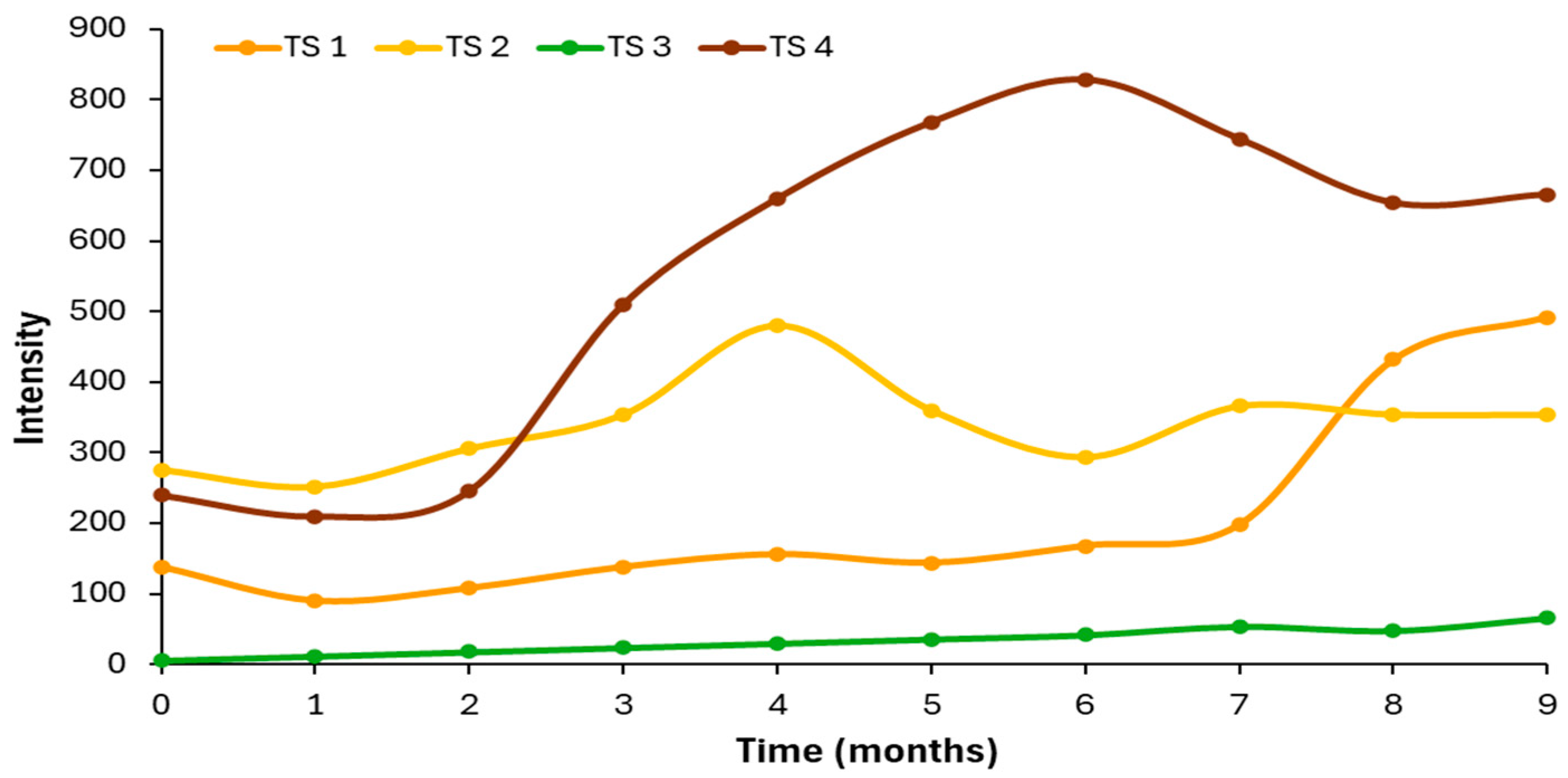

3.3. Autofluorescence Spectral Analysis of the Control Virgin Oil (AC) During Storage

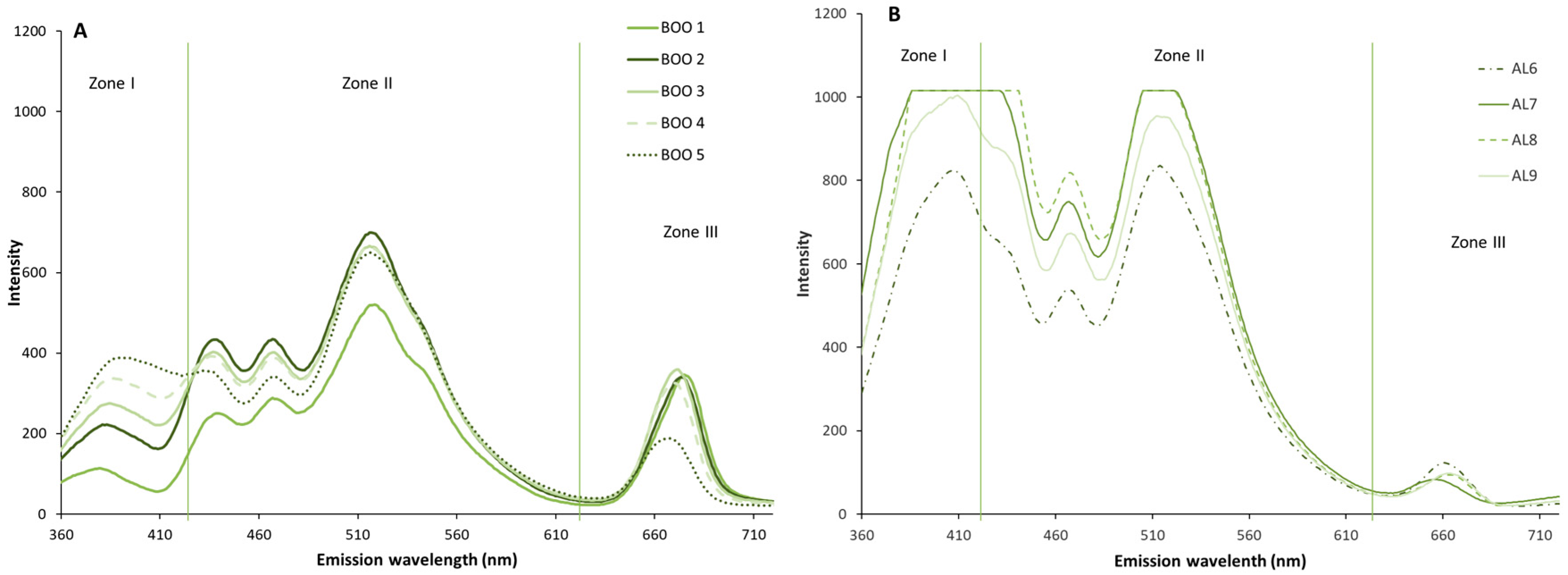

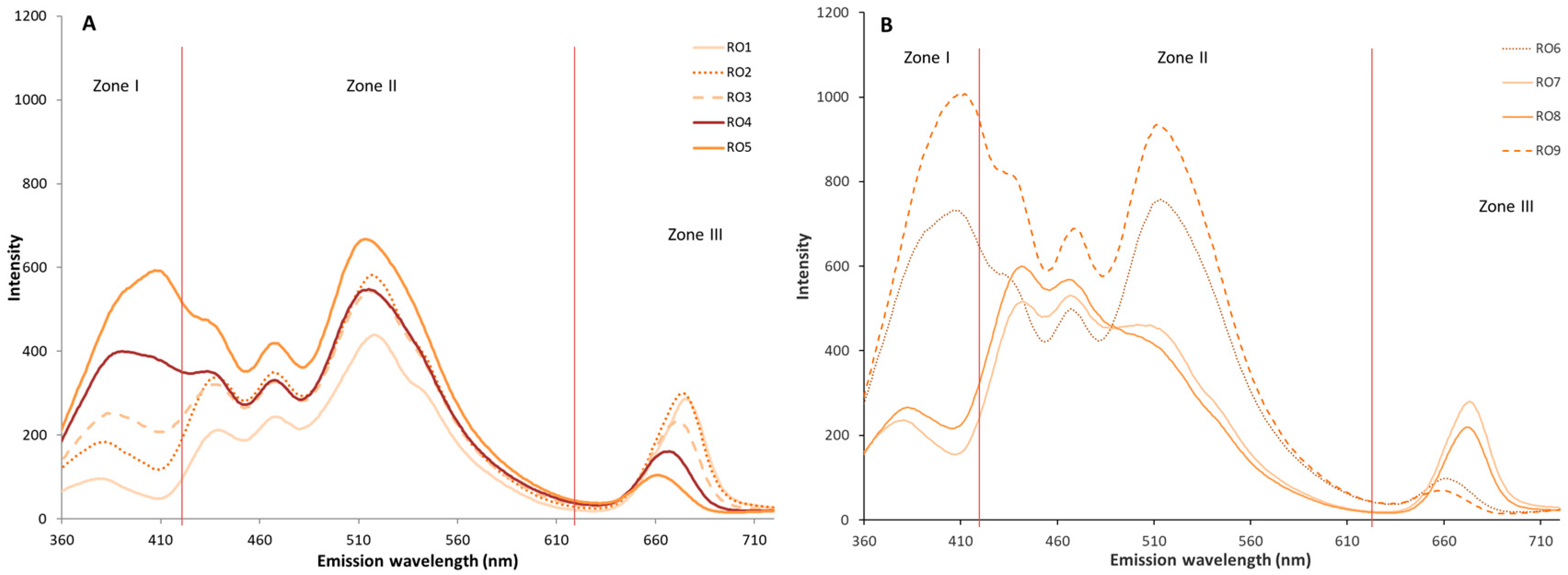

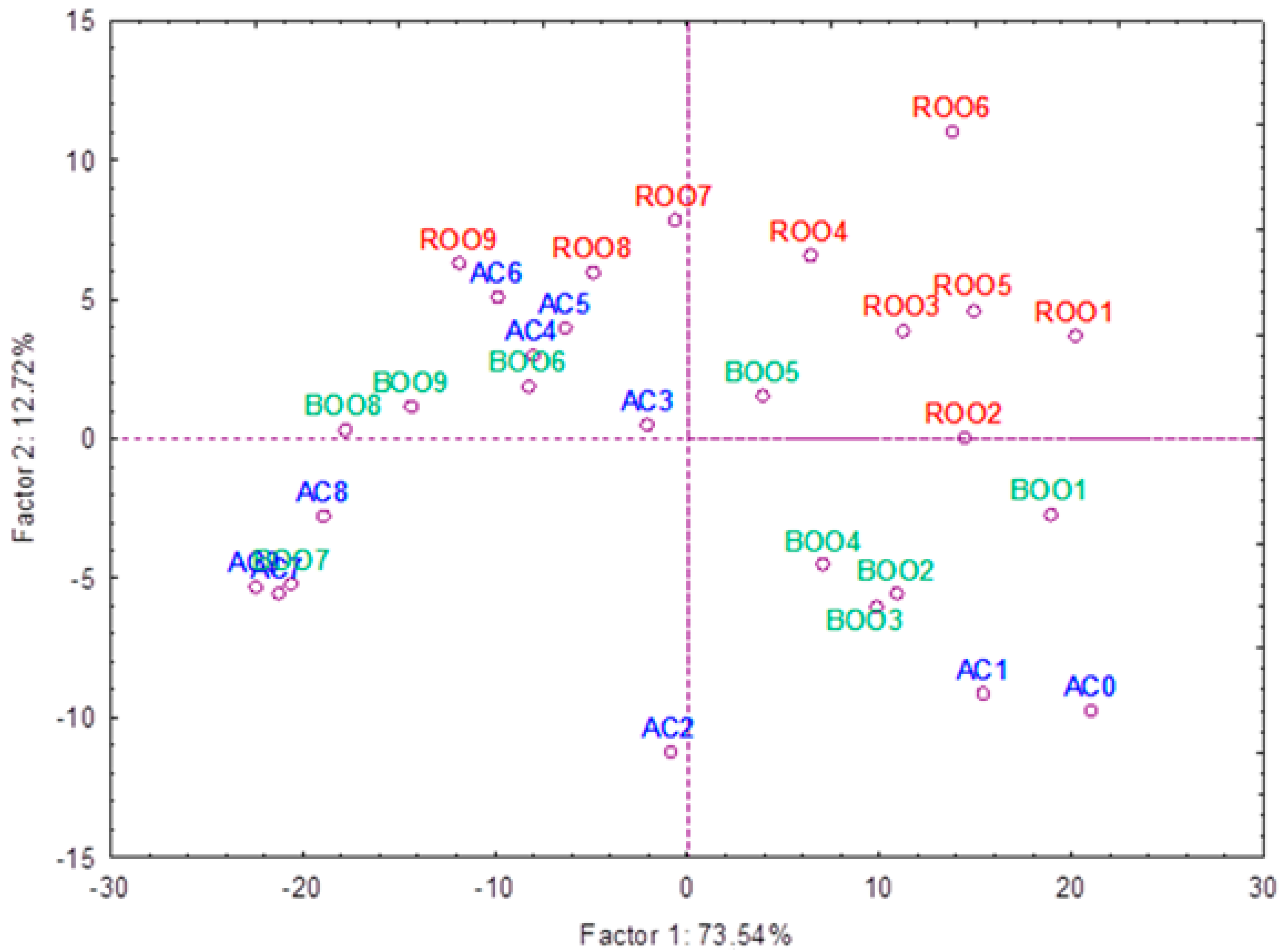

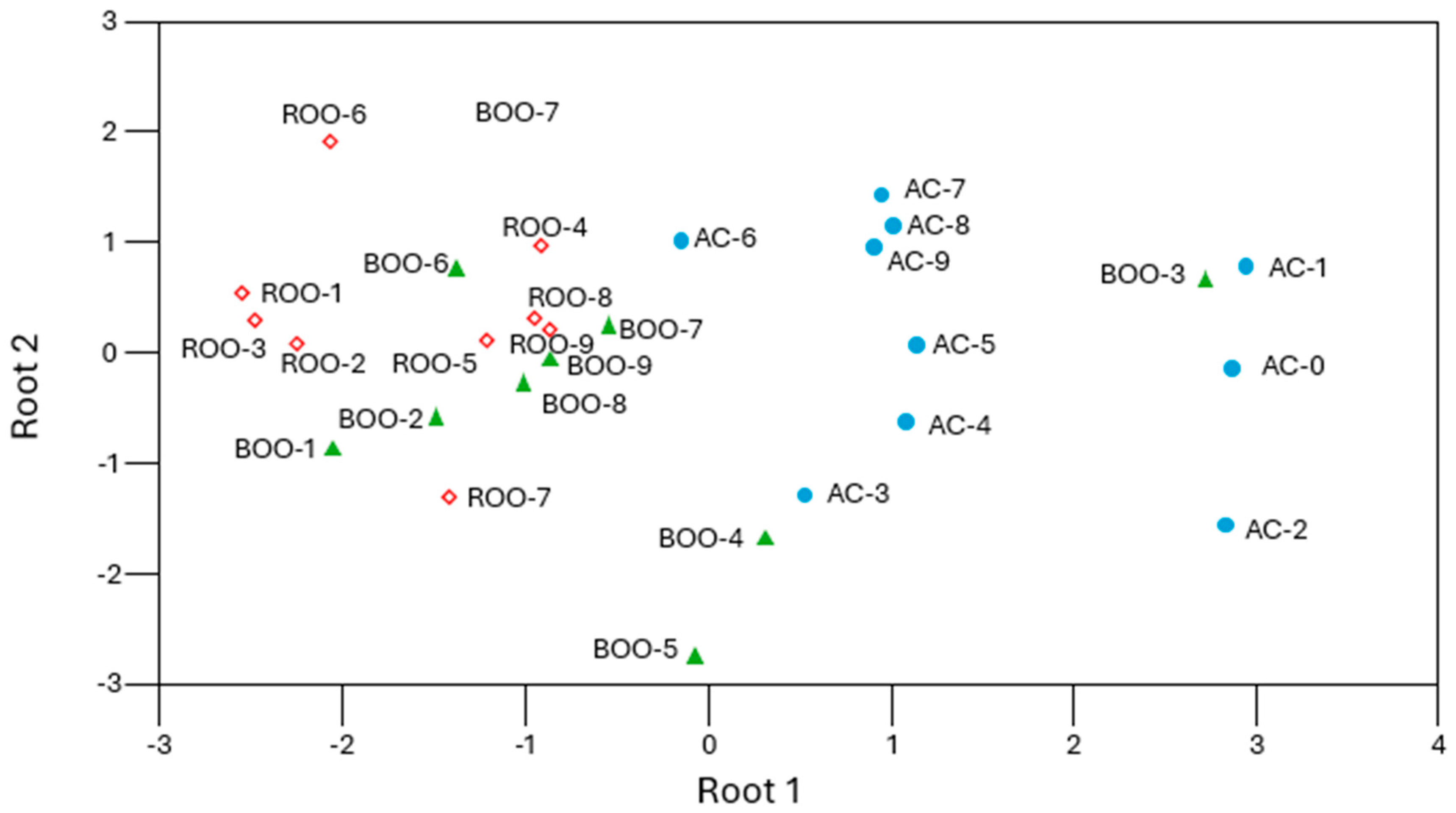

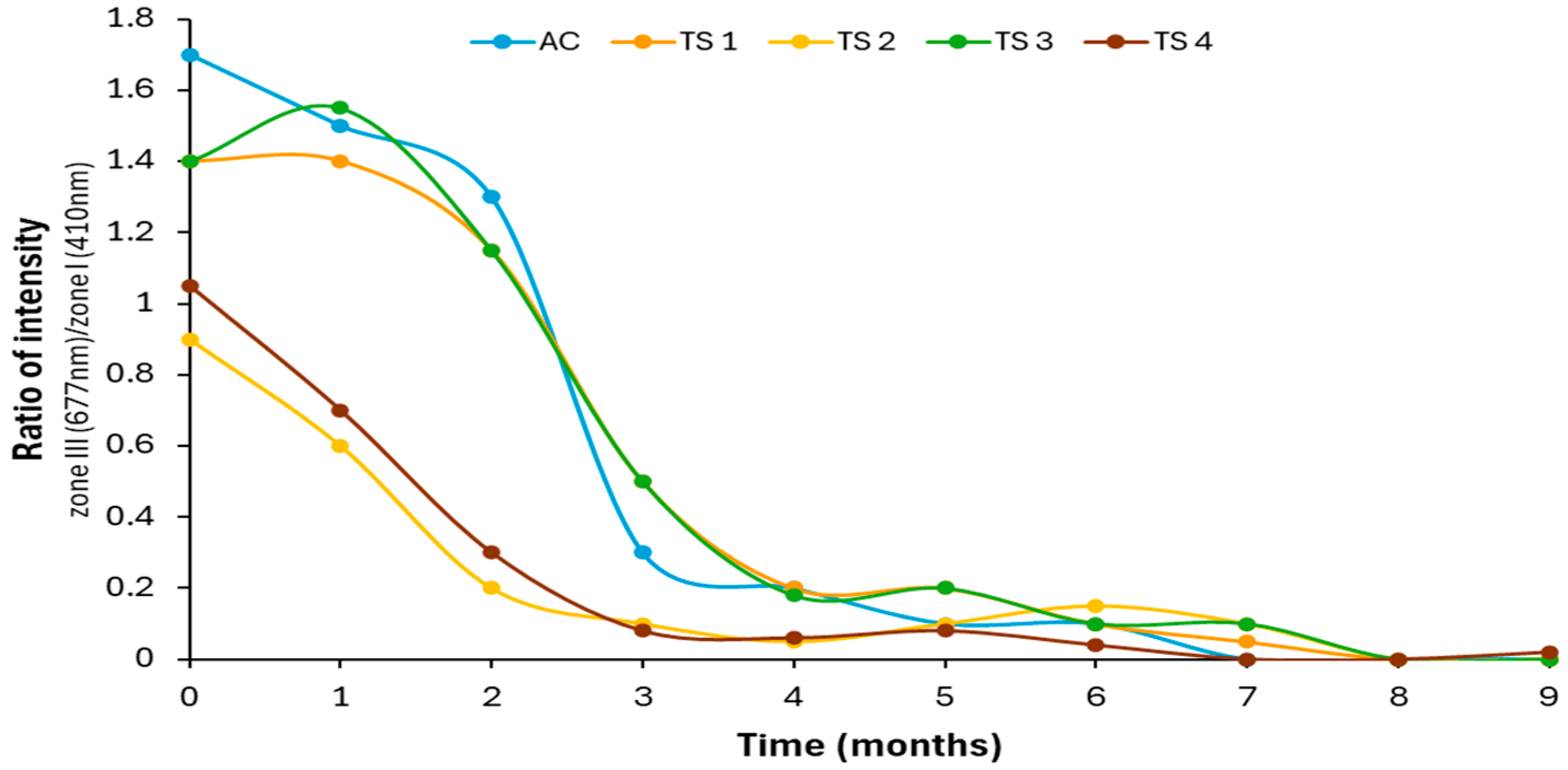

3.4. Comparative Study of Autofluorescence Spectra in Flavored and Unflavored Virgin Olive Oils

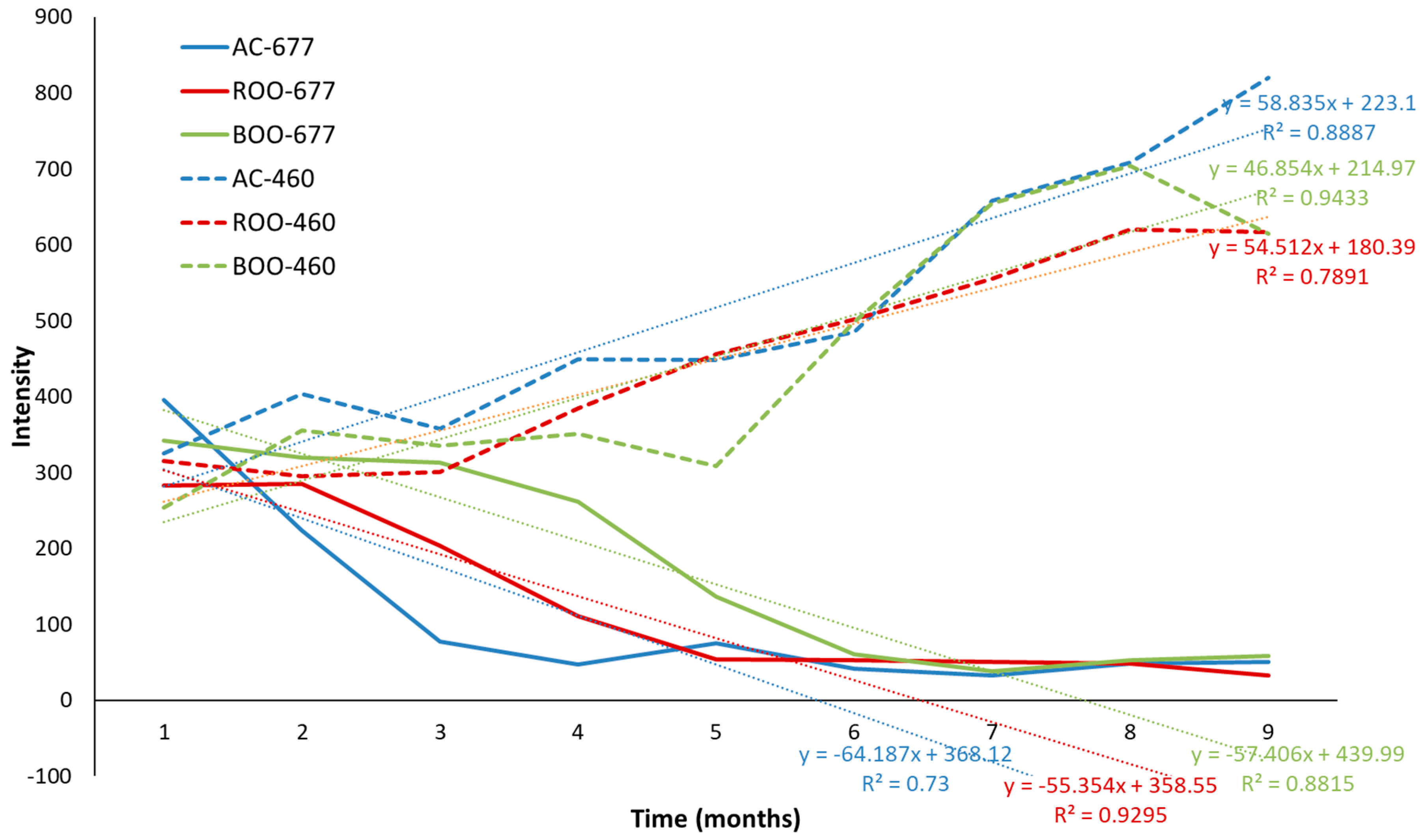

3.5. Development and Validation of Predictive Models for Olive Oil Degradation Based on Autofluorescence Spectra

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Z.; Jia, X.; Zheng, Z.; Lu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, B.; Xiao, J. Chemical composition and nutritional function of olive (Olea europaea L.): A review. Phytochem Rev. 2018, 17, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.; Ait Edjoudi, D.; Cordero-Barreal, A.; Farrag, M.; Varela-García, M.; Torrijos-Pulpón, C.; Ruiz-Fernández, C.; Capuozzo, M.; Ottaiano, A.; Lago, F.; et al. Oleocanthal, an Antioxidant Phenolic Compound in Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO): A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Its Potential in Inflammation and Cancer. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskou, D.; Clodoveo, M.L. Olive Oil Processing, Characterization, and Health Benefits. Foods 2020, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, R.M.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Farag, M.; Alagawany, M.; Hassan, F.; Elnesr, S.S.; Elwan, H.A.M.; Qiu, H.; et al. Olive Oil: Nutritional Applications, Beneficial Health Aspects and its Prospective Application in Poultry Production. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 723040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Parisi, A.; Normanno, G. Polyphenols as Emerging Antimicrobial Agents. In Emerging Modalities in Mitigation of Antimicrobial Resistance, 1st ed.; Akhtar, N., Singh, K.S., Prerna, Goyal, D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 219–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.T.; Przybylski, R. Olive Oil Oxidation. In Handbook of Olive Oil, 1st ed.; Aparicio, R., Harwood, J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 479–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi-Nodeh, F.; Farhoosh, R.; Sharif, A. Frying stability time of olive oils estimated from the oxidative stability index. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, M.; García, A.; García, P.; Garrido, A.; Romero, C. Antioxidant activity of olive phenols in oil and in water emulsion. Food Chem. 2007, 108, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedec, D.; Hanganu, D.; Tiperciuc, B.; Olah, N.K.; Oniga, I.; Gheldiu, A.M. Functional properties and antioxidant activity of selected herbal extracts and essential oils. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montaña, E.J.; Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; Morales, M.T. Effect of Flavorization on Virgin Olive Oil Oxidation and Volatile Profile. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, N.; Sari, F.; Velioglu, Y.S. Effect of extraction method on quality and stability of olive oil. Food Chem. 2010, 98, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Enhanced antioxidant activity of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) extracts in virgin olive oil by encapsulation in cyclodextrins. Food Chem. 2017, 238, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriuso, B.; Astiasarán, I.; Ansorena, D. A review of analytical methods measuring lipid oxidation status in foods: A challenging task. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 236, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, N.; Aparicio, R.; García-González, D.L. Chemical changes of thermoxidized virgin olive oil determined by excitation-emission fluorescence spectroscopy (EEFS). J. Am. Oil Chem Soc. 2012, 89, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, J.A.; Yousfi, K.; Martínez, M.C.; García, J.M. Rapid determination of olive oil chlorophylls and carotenoids by using visible spectroscopy. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolayemi, O.S.; Tokatli, F.; Ozen, B. UV–Vis spectroscopy for the estimation of variety and chemical parameters of olive oils. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4138–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lešnik, S.; Furlan, V.; Bren, U. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): Extraction techniques, analytical methods and health-promoting biological effects. Phytochem Rev. 2021, 20, 1273–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Silva, W.M.; de Oliveira, M.S.; de Oliveira, R.N.; de Oliveira, W.P. Basil essential oil: Methods of extraction, chemical composition, biological activities, and food applications. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Li, R.; Jiang, Z.T.; Shi, M.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Jia, B.; Lu, T.X.; Wang, H. Detection of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration with Edible Oils Using Front-Face Fluorescence and Visible Spectroscopies. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2018, 95, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Tornero, E.; Fernández, A.; Durán-Merás, I.; Martín-Vertedor, D. Fluorescence monitoring oxidation of extra virgin olive oil packed in different containers. Molecules 2022, 27, 7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabood, F.; Boqué, R.; Folcarelli, R.; Busto, O.; Jabeen, F.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Hussain, J. The effect of thermal treatment on the enhancement of detection of adulteration in extra virgin olive oils by synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy and chemometric analysis. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 161, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimoglu, Z.; Tontul, I.; Soylu, A.; Gulen, K.; Topuz, A. The oxidative stability of flavoured virgin olive oil: The effect of the water activity of rosemary. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 2080–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Trade Standard Applying to Olive Oils and Olive-Pomace Oils; COI/T.15/Doc. No 3/Rev.20; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Method for the Determination of Peroxide Value in Olive Oil; COI/T.20/Doc. No 17/Rev.4; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Method for the Determination of Free Fatty Acids in Olive Oil; COI/T.20/Doc. No 34/Rev.4; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Spectrophotometric Investigation in the Ultraviolet; COI/T.20/Doc. No 19/Rev.5; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Method for the Determination of Fatty Acid Composition; COI/T.20/Doc. No 24/Rev.4; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Council (IOC). Method for the Organoleptic Assessment of Virgin Olive Oil; COI/T.20/Doc. No 15/Rev.11; International Olive Council: Madrid, Spain, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Siano, F.; Vasca, E.; Picariello, G. Accurate determination of total biophenols in unfractionated extra-virgin olive oil with the fast blue BB assay. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 130990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Oil Chemists’ Society (AOCS). Official Method Cd 12b-92 (Reapproved 2017): Oil Stability Index (OSI); AOCS: Urbana, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska, E.; Górecki, T.; Khmelinskii, I.V.; Sokorski, M.; Koziol, J. Clasification of edible oils using synchronous scanning fluorescence spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2005, 89, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano Díaz, T.; Durán Merás, I.; Correa, C.A.; Roldán, B.; Rodríguez Cáceres, M.I. Simultaneous fluorometric determination of chlorophylls a and b and pheophytins a and b in olive oil by partial least squares calibration. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6934–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimet, F.; Ferre, J.; Boqué, R.; Rius, F.X. Application of unfold principal component analysis and parallel factor analysis to the exploratory analysis of olive oils by means of excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. Acta 2004, 515, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, A.; García-González, D.L.; Morales, M.T.; Aparicio, R. Detection of the presence of refined hazelnut oil in refined olive oil by fluorescence sprectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2068–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Merás, I.; Domínguez Manzano, J.; Airado Rodríguez, D.; Muñoz de la Peña, A. Detection and quantification of extra virgin olive oil adulteration by means of autofluorescence excitation-emission profiles combined with multi-way classification. Talanta 2018, 178, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastra-Mejias, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Torreblanca-Zanca, A.; Aroca-Santos, R.; Cancilla, J.C.; Sepulveda-Diaz, J.E.; Torrecilla, J.S. Cognitive fluorescence sensing to monitor the storage conditions and locate adulterations of extra virgin olive oil. Food Control. 2019, 103, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y.; Xiaoxiao, S.; Xianon, S.; Baoukun, Q.; Zhongjian, W.; Yang, L.; Lianzhou, J. Rosemary extract can be used as a synthetic antioxidant to improve vegetable oil oxidative stability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 80, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, F.; Bilancia, M.T.; Pasqualone, A.; Sikorska, E.; Gomes, T. Influence of the exposure to light on extra virgin olive oil quality during storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 221, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo-Prieto, A.; Tena, N.; Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; García-González, D.L.; Sikorska, E. Monitoring virgin olive oil shelf-life by fluorescence spectroscopy and sensory characteristics: A multidimensional study carried out under simulated market conditions. Foods 2020, 9, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Quality Parameter | AC | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organoleptic characteristics | Median of defect | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Median of fruity | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Physicochemical parameters | K232 () | 1.49 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.08 | 1.93 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.4 | 1.84 ± 0.7 |

| K270 () | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | |

| Peroxide value (meq O2/kg) | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| Free acidity (% p/p oleic acid) | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | |

| Other characteristics | Rancimat oxidative stability index (100 °C) | 41.00 ± 0.9 | 38.71 ± 0.8 | 22.95 ± 0.7 | 82.80 ± 0.9 | 53.70 ± 0.8 |

| Total phenols (mg gallic acid equivalents/kg) | 323 ± 9 | 270 ± 5 | 340 ± 6 | 590 ± 8 | 420 ± 6 | |

| Category | AOVE | AOVE | AOVE | AOVE | AOV | |

| Excitation Wavelength (λex nm) | 330 | 350 | 370 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrum Zone (λem nm) | SDr | CVr | SDR | CVR | SDr | CVr | SDR | CVR | SDr | CVr | SDR | CVR |

| Zone I (360–420 nm) | 17.71 | 5.53 | 34.11 | 8.92 | 19.47 | 5.70 | 37.64 | 11.07 | 24.13 | 6.72 | 39.32 | 11.56 |

| Zone II (420–620 nm) | 25.41 | 6.81 | 34.75 | 9.87 | 32.69 | 8.22 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Zone III (620–720 nm) | 1.64 | 2.85 | 5.45 | 9.27 | 2.35 | 3.61 | 6.02 | 9.31 | 4.01 | 5.72 | 7.12 | 10.17 |

| Emission Wavelength (nm) | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| 361 | 4.703999 | 0.012655 |

| 362 | 4.573701 | 0.014166 |

| 363 | 4.469833 | 0.015505 |

| 364 | 4.295164 | 0.018057 |

| 365 | 4.127271 | 0.020921 |

| 366 | 4.055566 | 0.022284 |

| 367 | 3.992487 | 0.023559 |

| 368 | 3.840128 | 0.026957 |

| 369 | 3.681781 | 0.031030 |

| 370 | 3.356536 | 0.041515 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Díaz-Montaña, E.J.; Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; Tena, N.; Lobo-Prieto, A.; García-González, D.L.; Morales, M.T. Autofluorescence Profiling of Virgin Olive Oil: Impact of Rosemary and Basil Flavoring During Storage. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010062

Díaz-Montaña EJ, Aparicio-Ruiz R, Tena N, Lobo-Prieto A, García-González DL, Morales MT. Autofluorescence Profiling of Virgin Olive Oil: Impact of Rosemary and Basil Flavoring During Storage. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Montaña, Enrique J., Ramón Aparicio-Ruiz, Noelia Tena, Ana Lobo-Prieto, Diego L. García-González, and María Teresa Morales. 2026. "Autofluorescence Profiling of Virgin Olive Oil: Impact of Rosemary and Basil Flavoring During Storage" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010062

APA StyleDíaz-Montaña, E. J., Aparicio-Ruiz, R., Tena, N., Lobo-Prieto, A., García-González, D. L., & Morales, M. T. (2026). Autofluorescence Profiling of Virgin Olive Oil: Impact of Rosemary and Basil Flavoring During Storage. Antioxidants, 15(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010062