Dietary Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation Alleviates Heat Stress-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage by Activating Nrf2 Signaling in Rabbits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Animal Management

2.3. Isolation and Culture of Rabbit IECs

2.4. Biochemical Analysis

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.6. Flow Cytometric Assays

2.7. Immunofluorescence Assays

2.8. Intracellular ROS Assays

2.9. Western Blotting Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Impacts of CGA on the Serum Redox Status of HS-Expressed Rabbits (In Vivo)

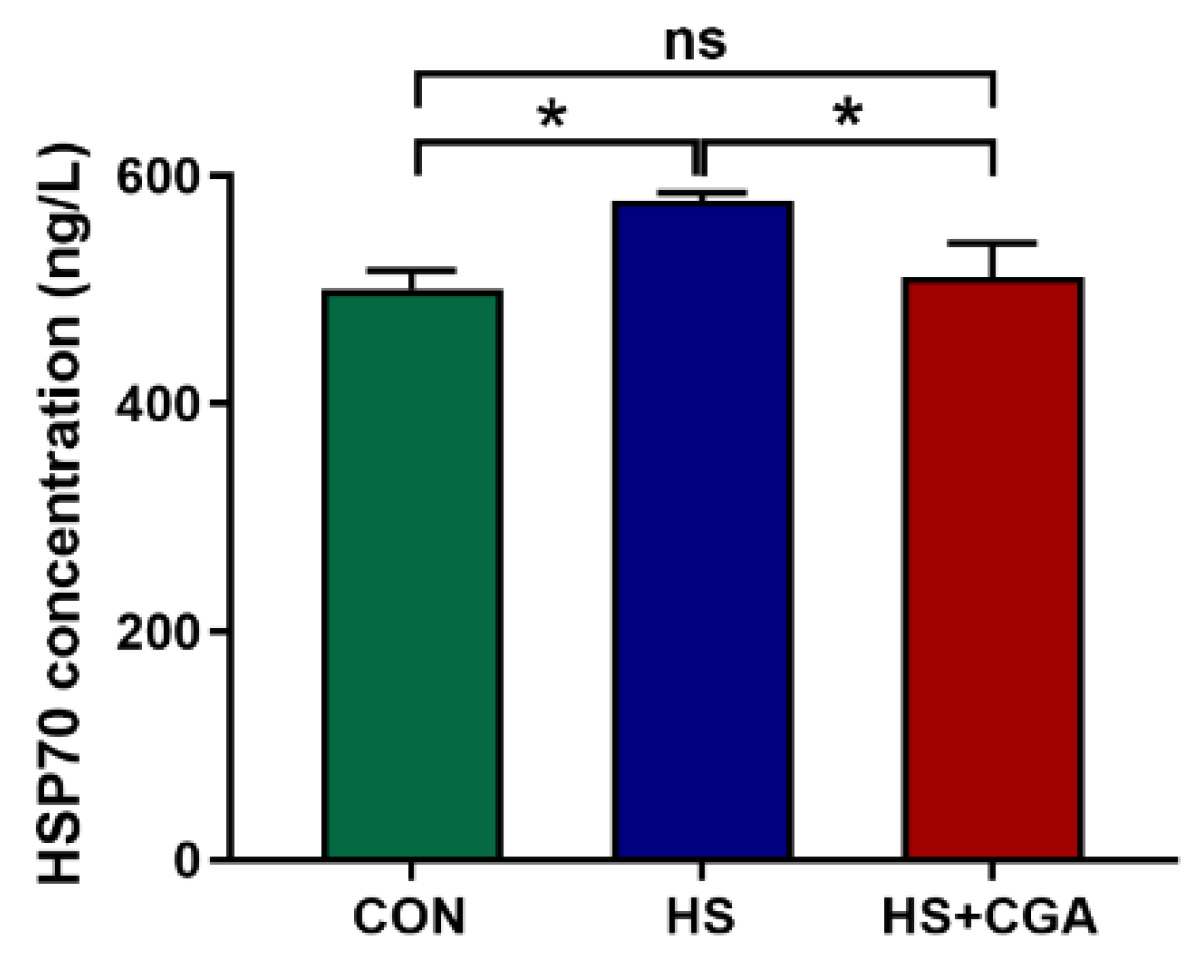

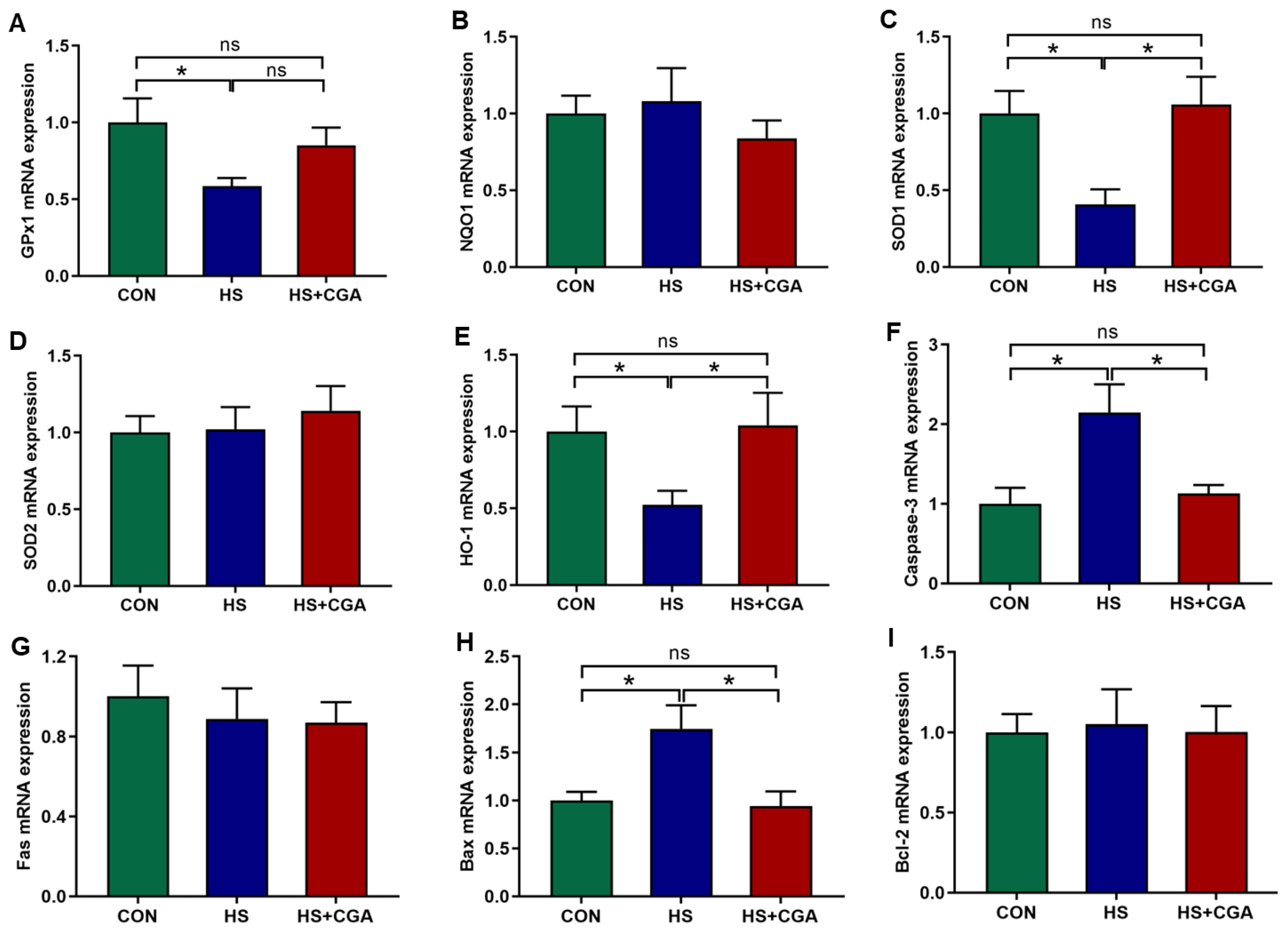

3.2. Impacts of CGA on HSP70 Level, and Antioxidant-Related and Apoptosis-Related Genes Expressions in the Jejunum of HS-Challenged Rabbits (In Vivo)

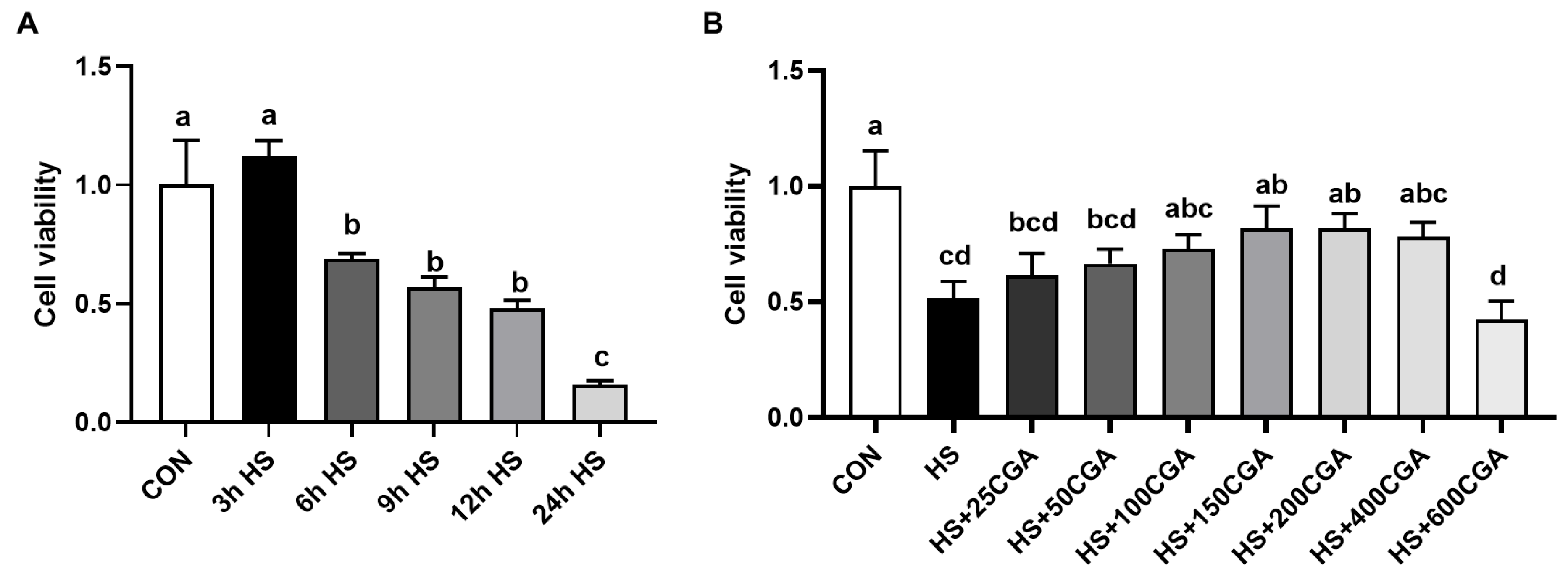

3.3. Cell Viability (In Vitro)

3.4. CGA Alleviates HS-Induced Cell Apoptosis in Rabbit IECs (In Vitro)

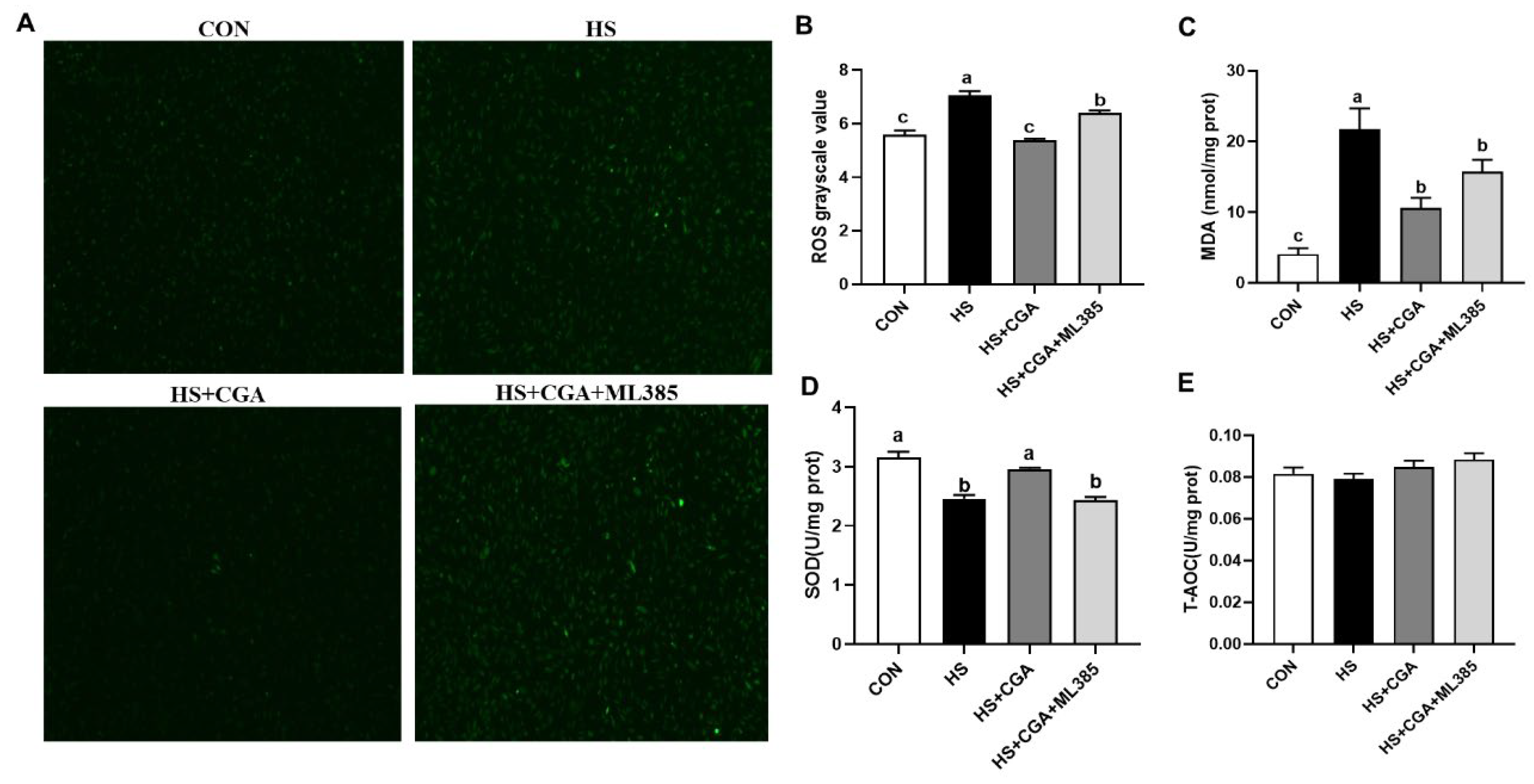

3.5. CGA Enhances the Antioxidant Capacity in HS-Challenged Rabbit IECs (In Vitro)

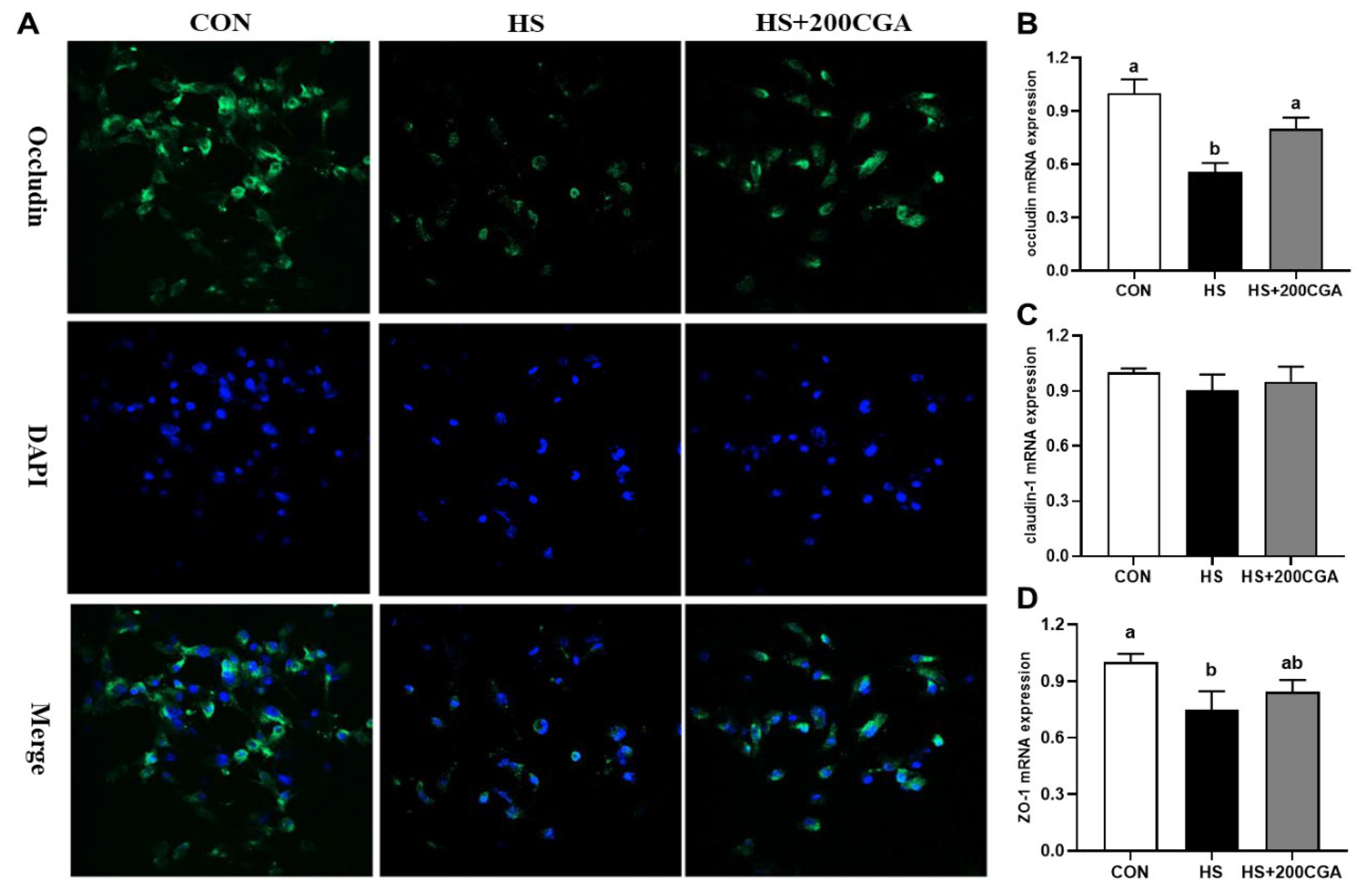

3.6. CGA Promotes the Expression of Tight Junction-Related Protein in HS-Challenged Rabbit IECs (In Vitro)

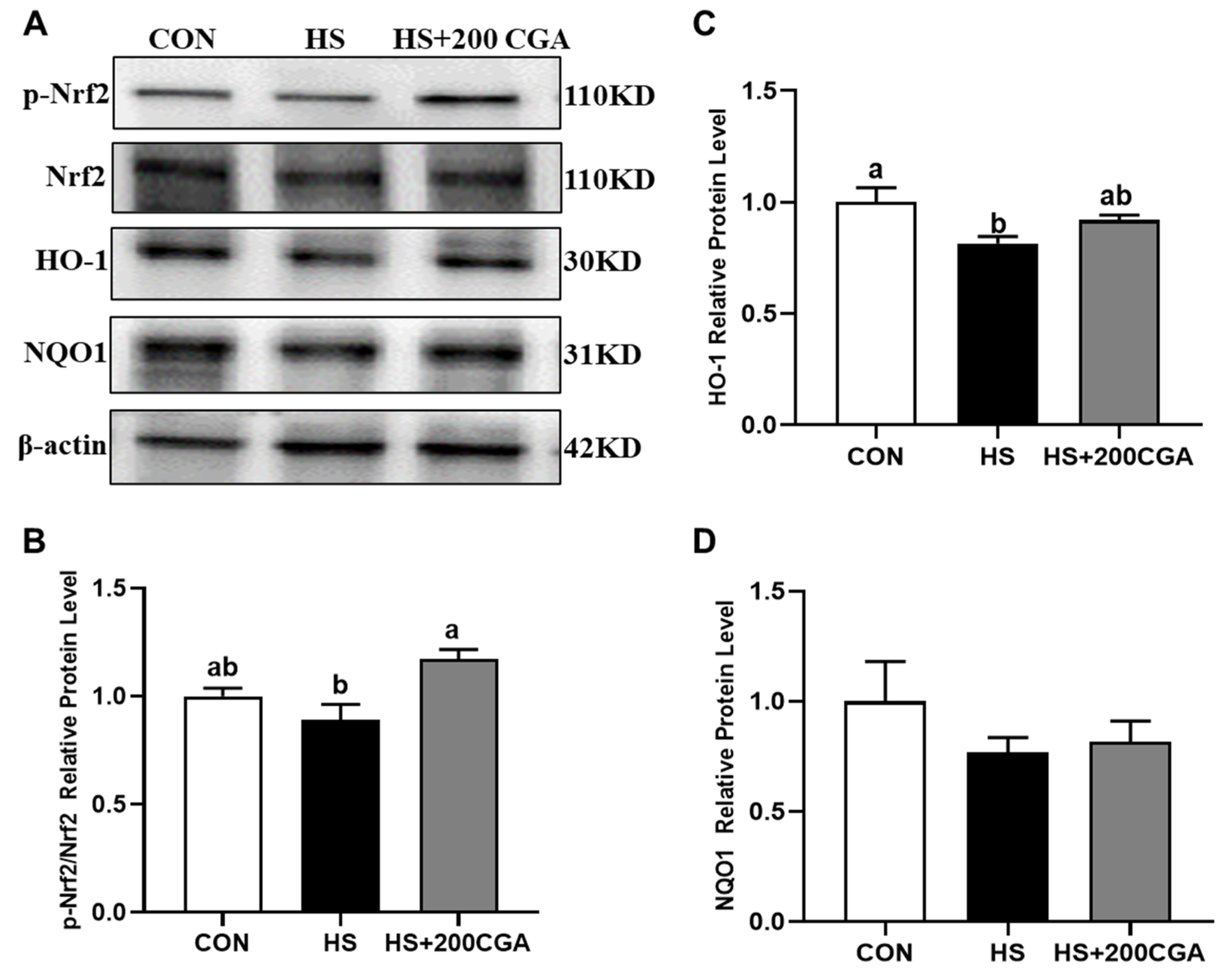

3.7. CGA Promotes the Activation of Nrf2 Signaling in HS-Challenged Rabbit IECs (In Vitro)

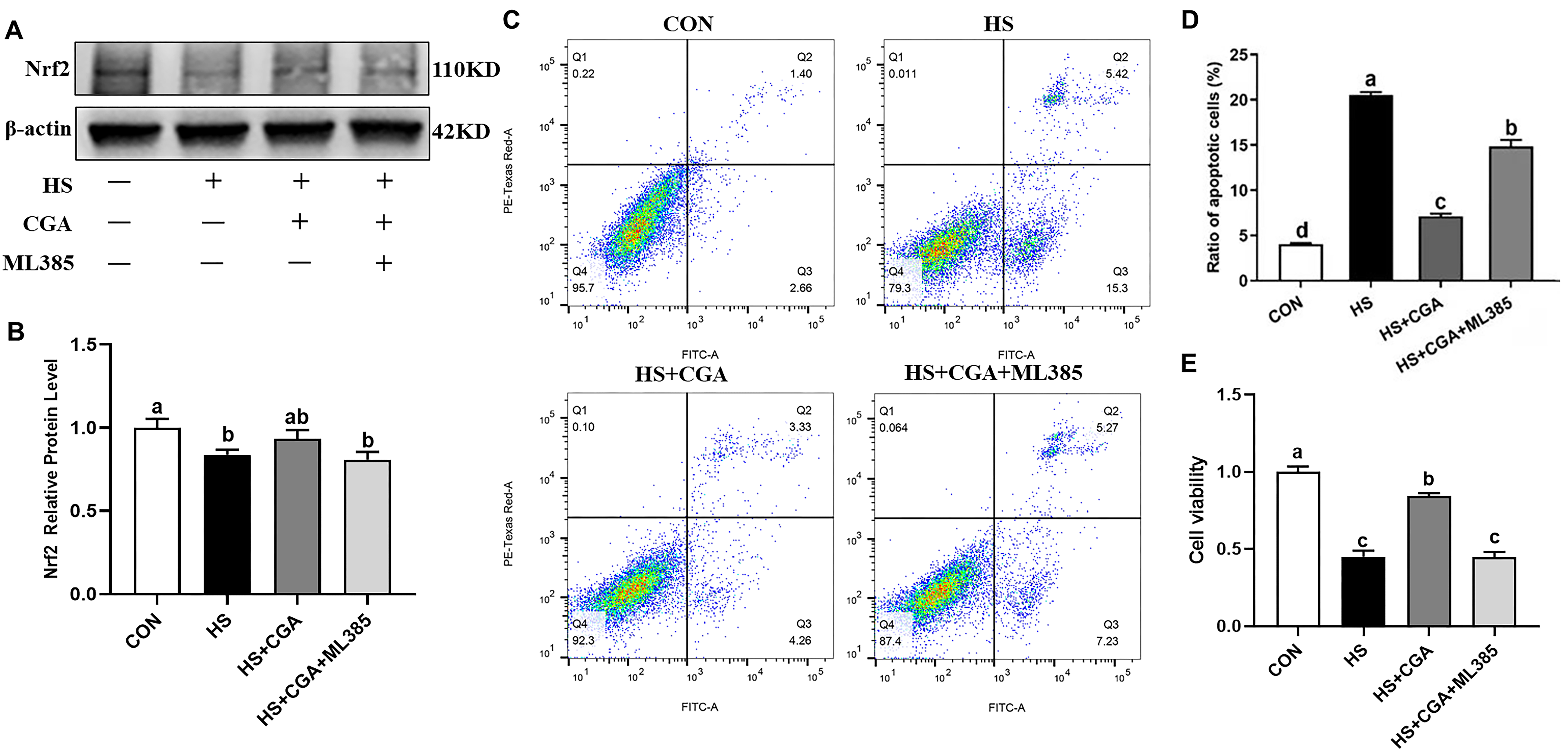

3.8. CGA Attenuates HS-Induced Oxidative Damage in Rabbit IECs via Nrf2 Signaling (In Vitro)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Escarcha, J.F.; Lassa, J.A.; Zander, K.K. Livestock under climate change: A systematic review of impacts and adaptation. Climate 2018, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matics, Z.; Gerencsér, Z.; Kasza, R.; Terhes, K.; Nagy, I.; Radnai, I.; Zotte, A.; Cullere, M.; Szendrő, Z. Effect of ambient temperature on the productive and carcass traits of growing rabbits divergently selected for body fat content. Animal 2021, 15, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marai, I.F.M.; Ayyat, M.S.; Abd El-Monem, U.M. Growth performance and reproductive traits at first parity of new zealand white female rabbits as affected by heat stress and its alleviation under egyptian conditions. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2001, 33, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, A.M.; Johnson, T.G.; Metwally, K.; Farghly, M.; Mahrose, K.M. Environmental heat stress in rabbits: Implications and ameliorations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, F.; Park, S.; Balasubramanian, B.; Liu, W. Impacts of heat stress on rabbit immune function, endocrine, blood biochemical changes, antioxidant capacity and production performance, and the potential mitigation strategies of nutritional intervention. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 906084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeid, T.A.; Aljabeili, H.S.; Al-Homidan, I.H.; Volek, Z.; Barakat, H. Ramifications of heat stress on rabbit production and role of nutraceuticals in alleviating its negative impacts: An updated review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ji, Y. Heat stress-induced intestinal barrier impairment: Current insights into the aspects of oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 5438–5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The Impact of Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology: Focus on Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouayed, J.; Rammal, H.; Dicko, A.; Younos, C.; Soulimani, R. Chlorogenic Acid, a Polyphenol from Prunus Domestica (Mirabelle), with Coupled Anxiolytic and Antioxidant Effects. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 262, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajik, N.; Tajik, M.; Mack, I.; Enck, P. The Potential Effects of Chlorogenic Acid, the Main Phenolic Components In Coffee, On Health: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2215–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J. Chlorogenic acid attenuates oxidative stress-induced intestinal epithelium injury by co-regulating the PI3K/Akt and IκBα/NF-κB signaling. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic acid: A systematic review on the biological functions, mechanistic actions, and therapeutic potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, N.; Yang, X.; Du, E.; Huang, S.; Guo, W.; Zhang, W.; Wei, J. Effect of chlorogenic acid on intestinal inflammation, antioxidant status, and microbial community of young hens challenged with acute heat stress. Anim. Sci. J. 2021, 92, e13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Hanif, S.; Shukat, R.; Aleem, M.T.; Shaukat, I.; Almutairi, M.H.; Almutairi, B.O.; Hassan, M.; Rajput, S.A.; Huang, S.; et al. Immunological role of chlorogenic acid in broiler intestinal health under chronic heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Song, Z.; Ji, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, L.; Li, F. Chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned rabbits via modulating the intestinal epithelium functions and intestinal microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1027101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Li, F. Protective effect of chlorogenic acid on liver injury in heat-stressed meat rabbits. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 108, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yu, B.; Tian, G.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H. Culture and identification of jejunal epithelial cells isolated from neonatal rabbits in vitro. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 26, 1570–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Asaka, M.; Hirase, T.; Hashimoto-Komatsu, A.; Node, K. Rab5a-mediated localization of claudin-1 is regulated by proteasomes in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C87–C96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Shi, Y.; Tang, L.; Chen, L.; Fan, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, X.; Chen, S.; Lai, S. Heat stress affects faecal microbial and metabolic alterations of rabbits. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 817615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, O.A.; Ayedun, E.S.; Oyelade, W.A.; Oloruntola, O.D.; Daramola, O.T.; Ayodele, S.O.; Omoniyi, I.S. Protective effect of soursop (Annona muricata linn.) juice on oxidative stress in heat stressed rabbits. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2018, 60, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varasteh, S.; Braber, S.; Akbari, P.; Garssen, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J. Differences in susceptibility to heat stress along the chicken intestine and the protective effects of galacto-oligosaccharides. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Kitts, D.D. Role of chlorogenic acids in controlling oxidative and inflammatory stress conditions. Nutrients 2016, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.A.; Rollo, I.; Baker, L.B. Nutritional considerations to counteract gastrointestinal permeability during exertional heat stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 1754–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endale, H.T.; Tesfaye, W.; Mengstie, T.A. ROS induced lipid peroxidation and their role in ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1226044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhadj Slimen, I.; Najar, T.; Ghram, A.; Dabbebi, H.; Ben Mrad, M.; Abdrabbah, M. Reactive oxygen species, heat stress and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. A review. Int. J. Hyperth. 2014, 30, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, S.S.; Gupta, M.; Maurya, D.; Yadav, V.P.; Panda, R.P.; Singh, G.; Mohan, N.H.; Bhure, S.K.; Das, B.C.; Bag, S.; et al. Expression profile of HSP genes during different seasons in goats (Capra hircus). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kpodo, K.R.; Duttlinger, A.W.; Radcliffe, J.S.; Johnson, J.S. Time course determination of the effects of rapid and gradual cooling after acute hyperthermia on body temperature and intestinal integrity in pigs. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 87, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.; Gershon, D.; Fargnoli, J.; Holbrook, N. Discordant expression of heat shock protein mRNAs in tissues of heat-stressed rats. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 15275–15279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Jiménez, F.; García-Diego, F.; Vicente, J. Effect of gestational and lactational exposure to heat stress on performance in rabbits. World Rabbit Sci. 2017, 25, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, F.; Yin, P.; Zhao, H.; Luan, W.; Hou, X.; Zhong, Y.; Jia, D.; Zan, J.; Ma, W.; et al. Involvement of oxidative stress and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in heat stress-induced injury in the rat small intestine. Stress 2013, 16, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, P.; Braber, S.; Garssen, J.; Wichers, H.J.; Folkerts, G.; Fink-Gremmels, J.; Varasteh, S. Beyond heat stress: Intestinal integrity disruption and mechanism-based intervention strategies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Feng, L.; Su, Y.; Xu, D. Mycophenolic acid induces the intestinal epithelial barrier damage through mitochondrial ROS. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4195699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Tang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Heat stress induced IPEC-J2 cells barrier dysfunction through endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated apoptosis by p-eif2α/CHOP pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, B.; Chen, D.; Mao, X.; Zheng, P.; Luo, J.; He, J. Dietary chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned pigs through maintaining antioxidant capacity and intestinal digestion and absorption function. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Pi, D.; Leng, W.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Kang, P. Fish oil enhances intestinal barrier function and inhibits corticotropin-releasing hormone/corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 signalling pathway in weaned pigs after lipopolysaccharide challenge. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgorzynska, E.; Dziedzic, B.; Walczewska, A. An overview of the Nrf2/ARE pathway and its role in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, M.J.; Ferrándiz, M.L. Relevance of Nrf2 and heme oxygenase-1 in articular diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 157, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Naidu, S.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Regulating Nrf2 activity: Ubiquitin ligases and signaling molecules in redox homeostasis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2025, 50, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, C.; Mori, N. ML385, a selective inhibitor of Nrf2, demonstrates efficacy in the treatment of adult T-cell leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2025, 66, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, N.; Dupuis, J.H.; Yada, R.Y.; Kitts, D.D. Chlorogenic acid isomers directly interact with Keap 1-Nrf2 signaling in Caco-2 cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 457, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wu, F. Chlorogenic acid alleviates high glucose-induced HK-2 cell oxidative damage through activation of KEAP1/NRF2/ARE signaling pathway. Discov. Med. 2024, 36, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items 1 | CON | HS | HS+CGA | SEM | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 1.64 b | 2.53 a | 1.80 b | 0.087 | <0.001 |

| CAT (U/mL) | 3.46 a | 1.98 b | 3.12 a | 0.197 | 0.036 |

| GSH-Px (U/mL) | 201.64 | 211.29 | 210.86 | 2.992 | 0.126 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 74.21 a | 59.37 b | 79.03 a | 2.363 | <0.001 |

| T-AOC (U/mL) | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.021 | 0.371 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Ji, R.; Li, F.; Liu, L. Dietary Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation Alleviates Heat Stress-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage by Activating Nrf2 Signaling in Rabbits. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010002

Chen J, Ji R, Li F, Liu L. Dietary Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation Alleviates Heat Stress-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage by Activating Nrf2 Signaling in Rabbits. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiali, Rongmei Ji, Fuchang Li, and Lei Liu. 2026. "Dietary Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation Alleviates Heat Stress-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage by Activating Nrf2 Signaling in Rabbits" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010002

APA StyleChen, J., Ji, R., Li, F., & Liu, L. (2026). Dietary Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation Alleviates Heat Stress-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Damage by Activating Nrf2 Signaling in Rabbits. Antioxidants, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010002