The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) Gene Family in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): Identification, Classification, and Expression Responses in Leaves Under Abiotic Stresses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. Identification and Bioinformatic Analysis of the LcSOD Gene Family

2.3. Expression Patterns of the LcSOD Gene Family in Response to Abiotic Stresses

2.4. Physiological Parameters of Litchi Leaves in Response to Abiotic Stresses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of the LcSOD Genes

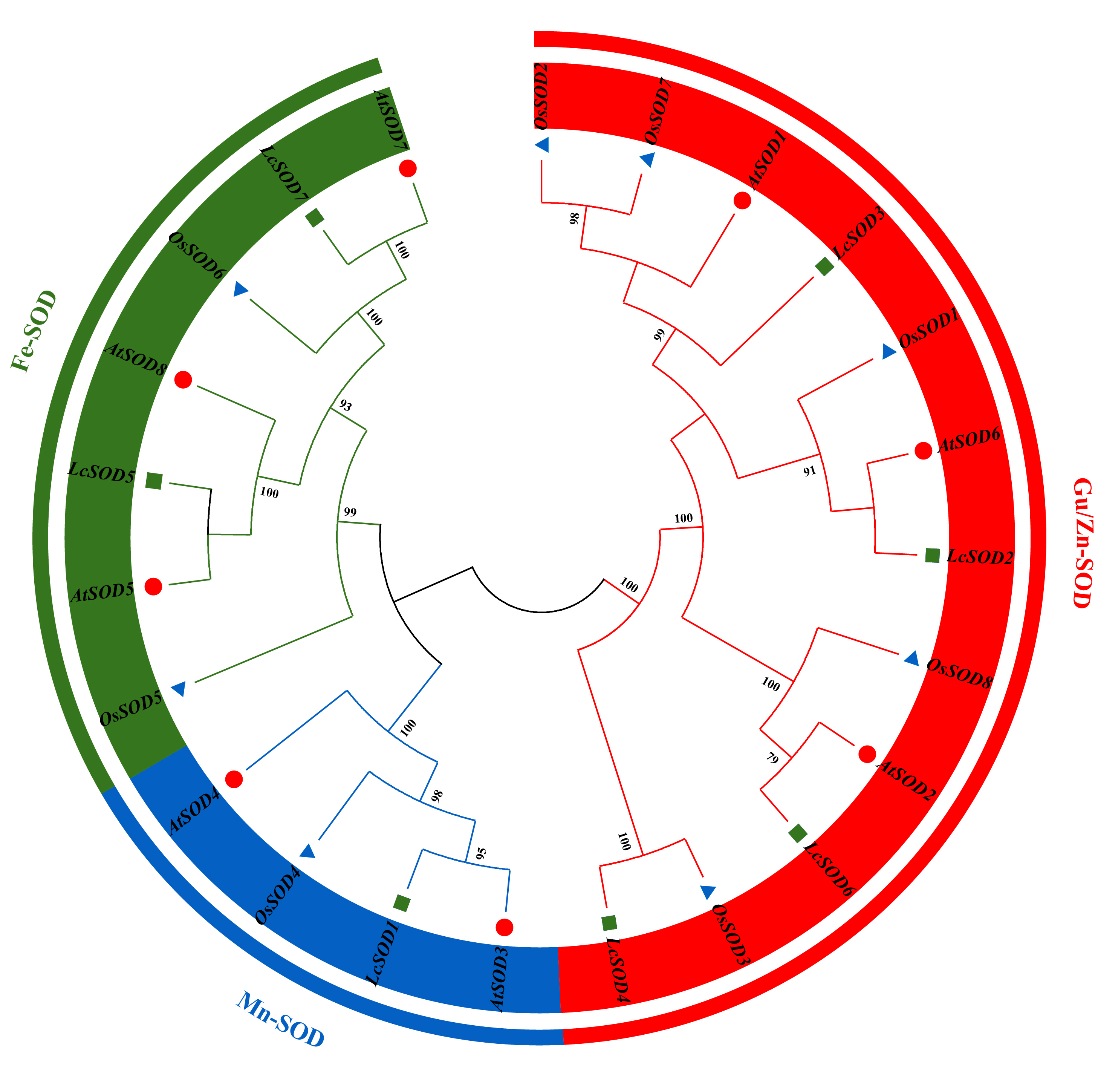

3.2. Evolution and Classification of the LcSOD Genes

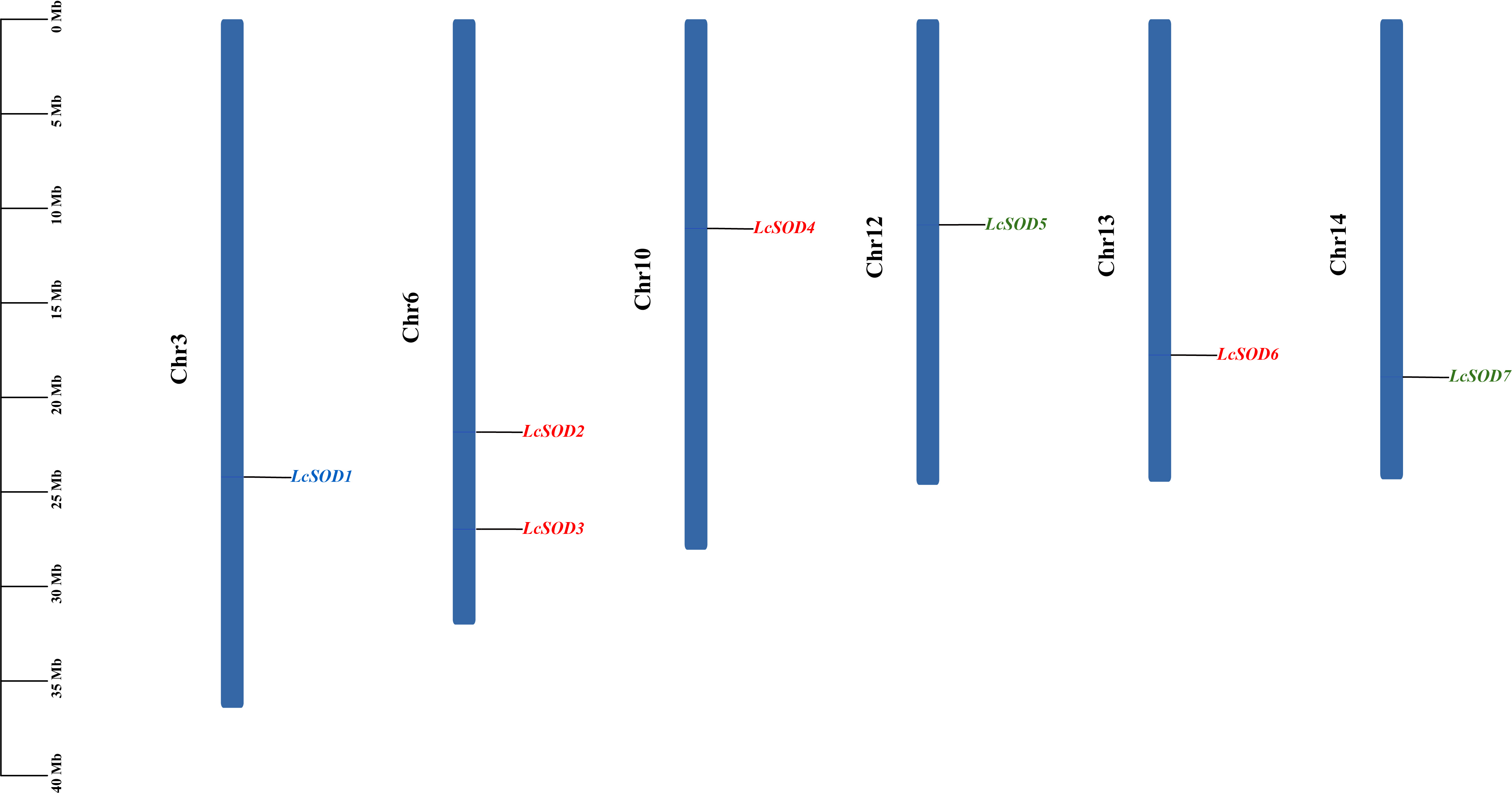

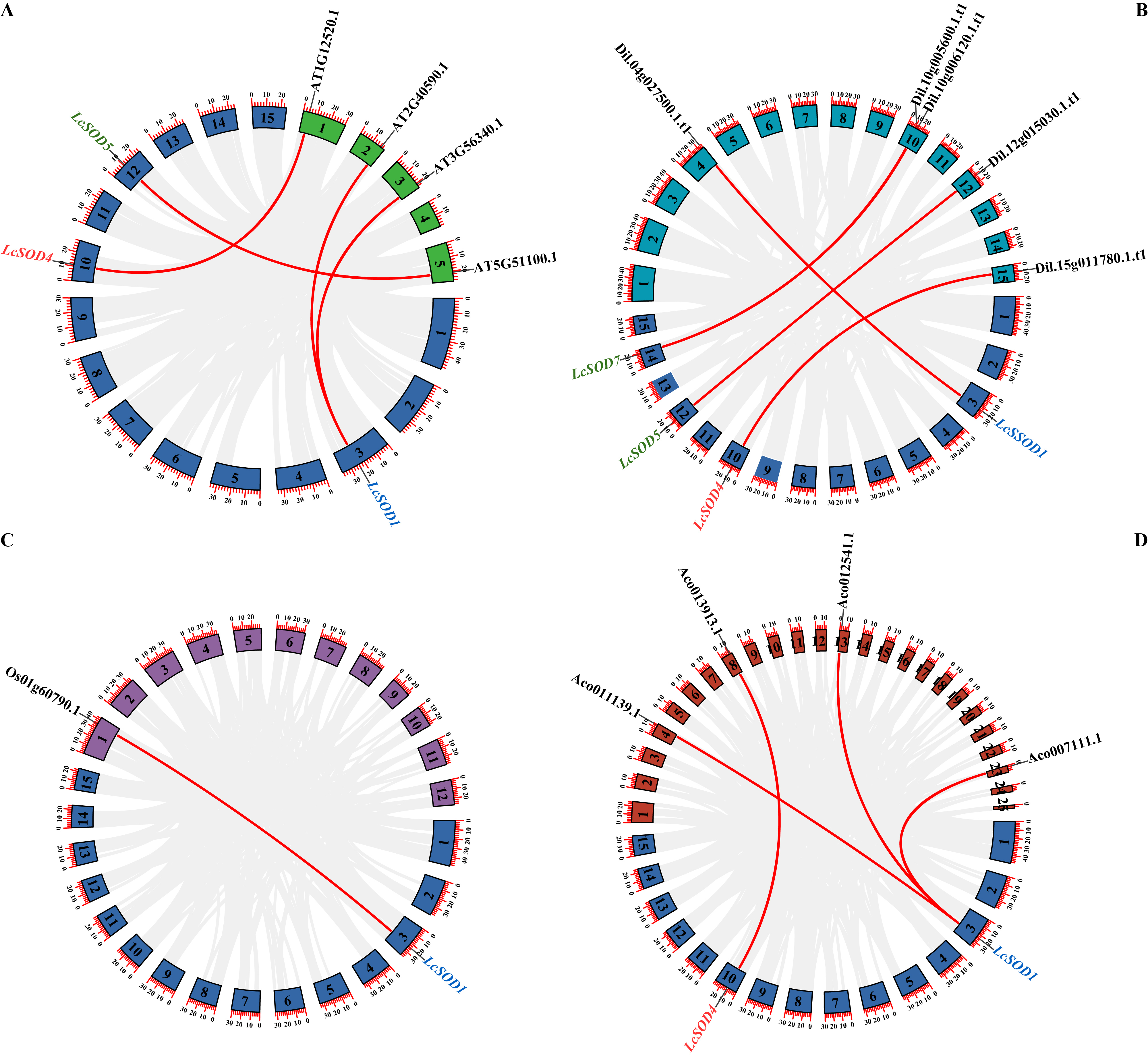

3.3. Chromosomal Distributions and Collinear Relationships of the LcSOD Genes

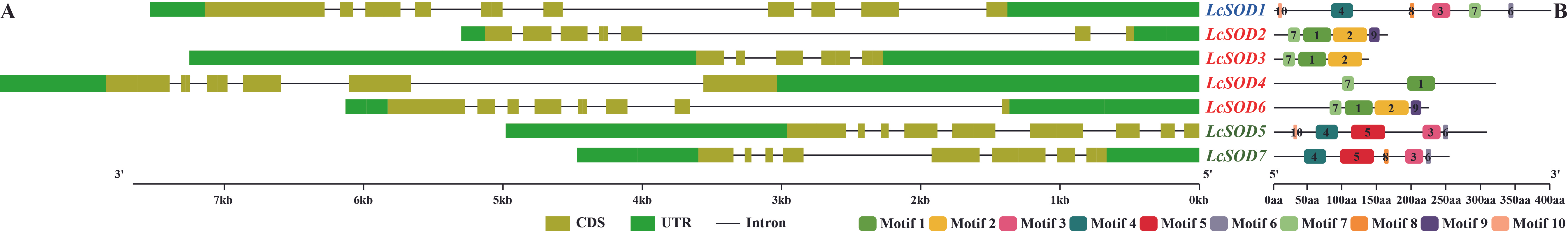

3.4. Phylogeny, Structures, and Motifs of the LcSOD Genes

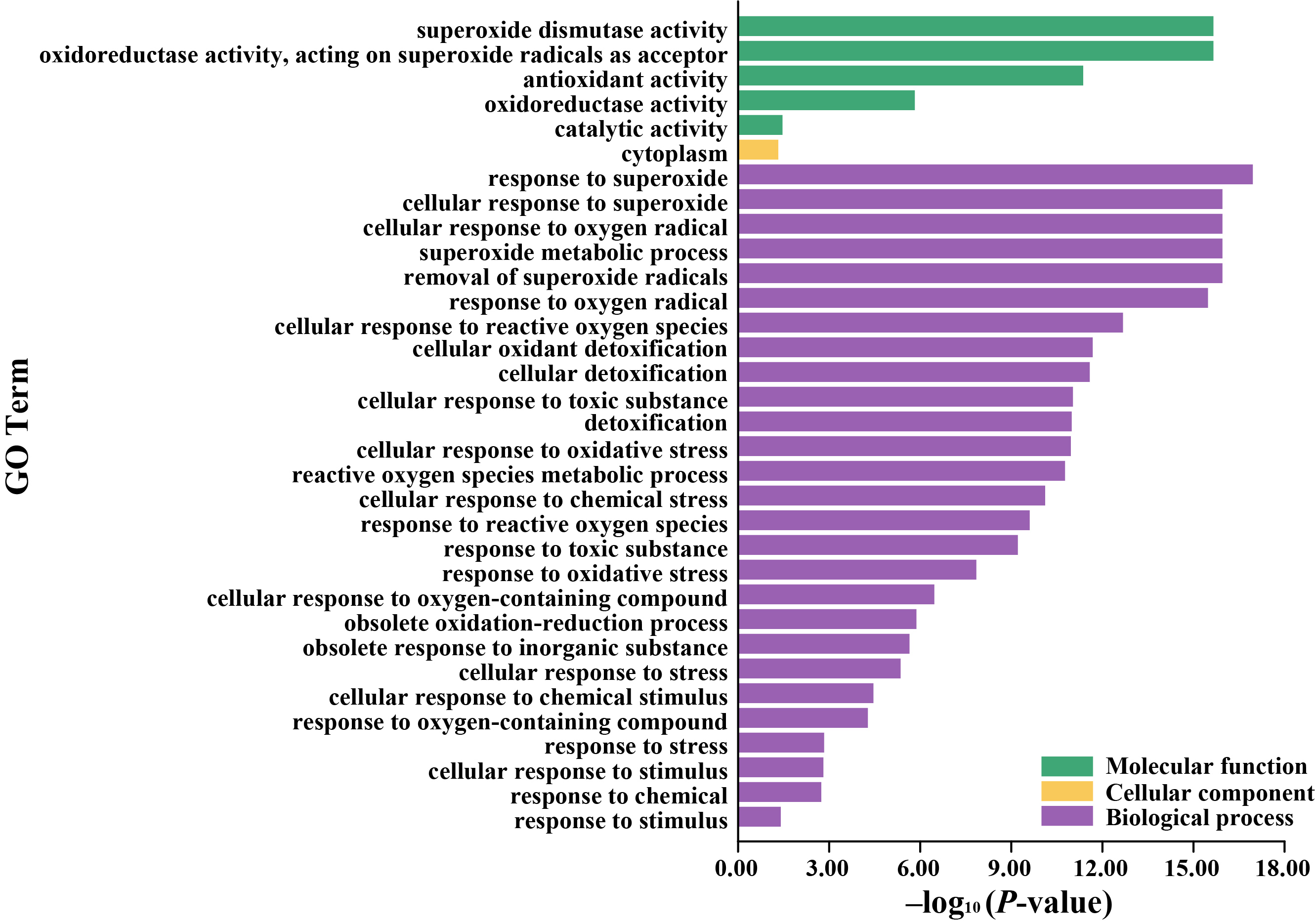

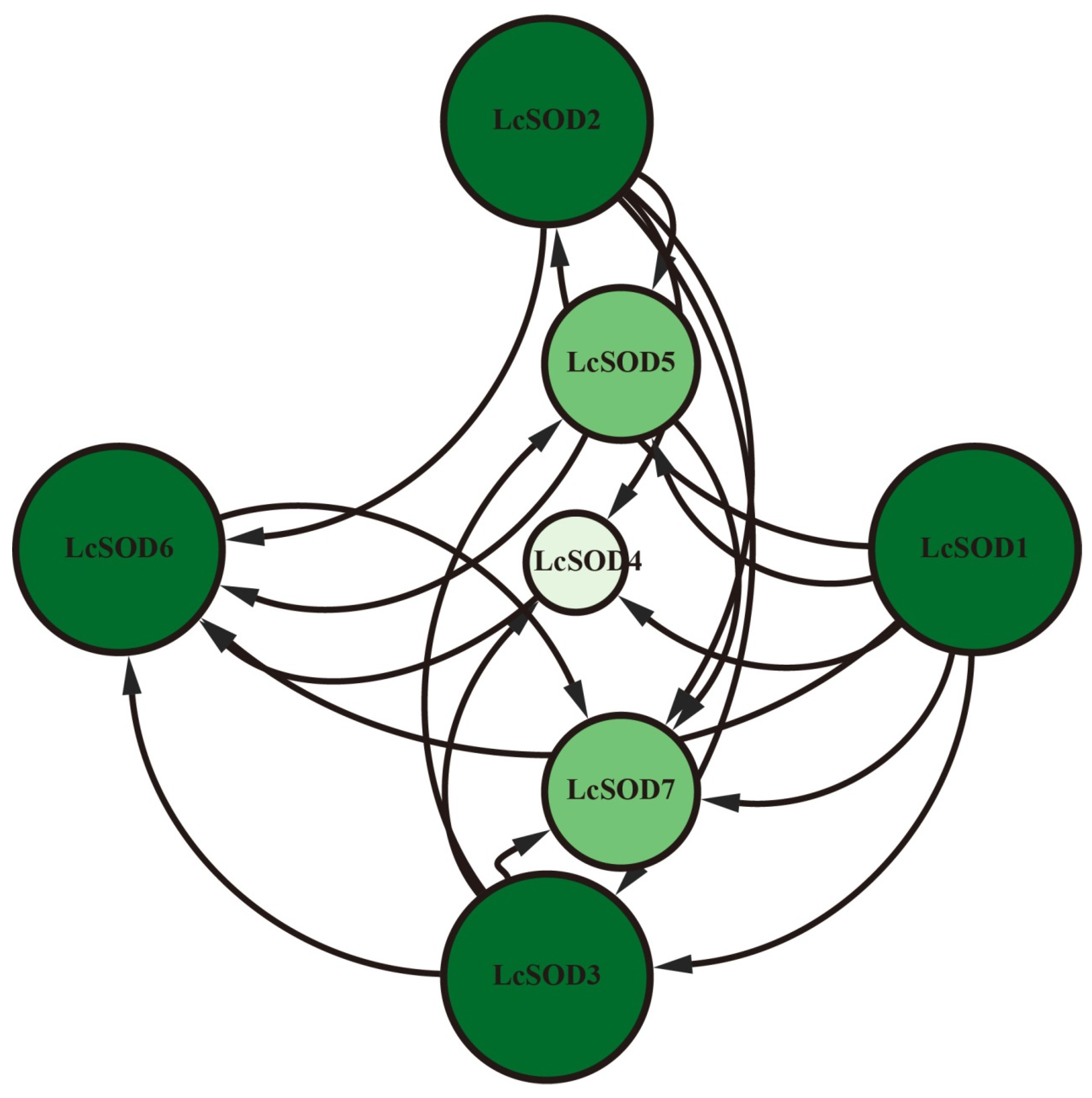

3.5. GO Enrichment and Protein-Protein Interaction Network of the LcSOD Genes

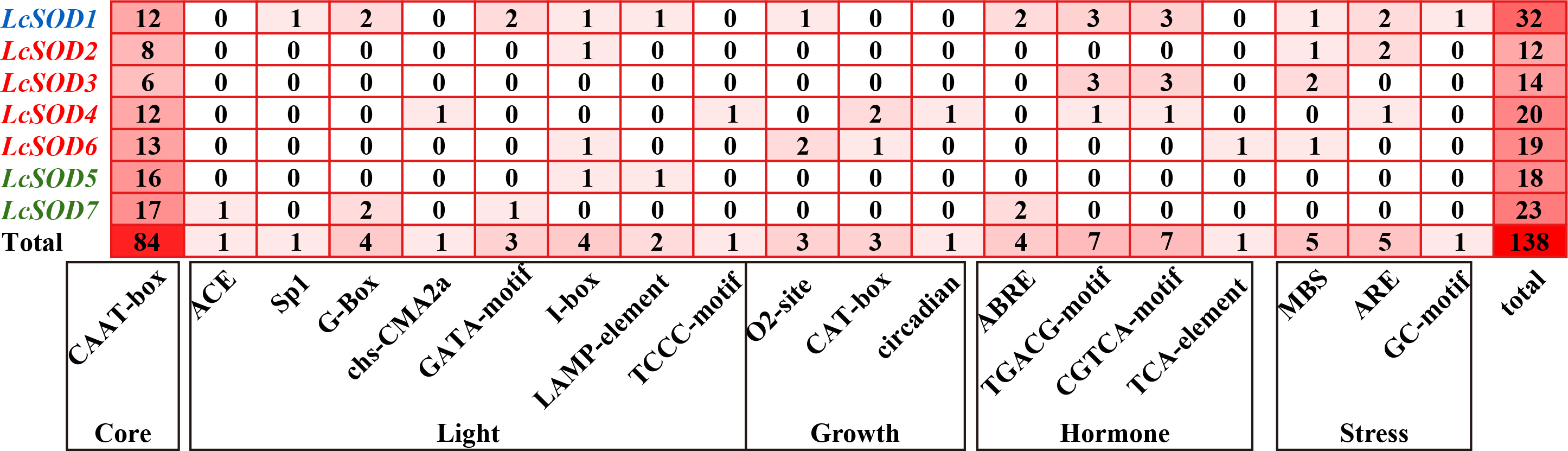

3.6. Cis-Acting Elements of the LcSOD Genes

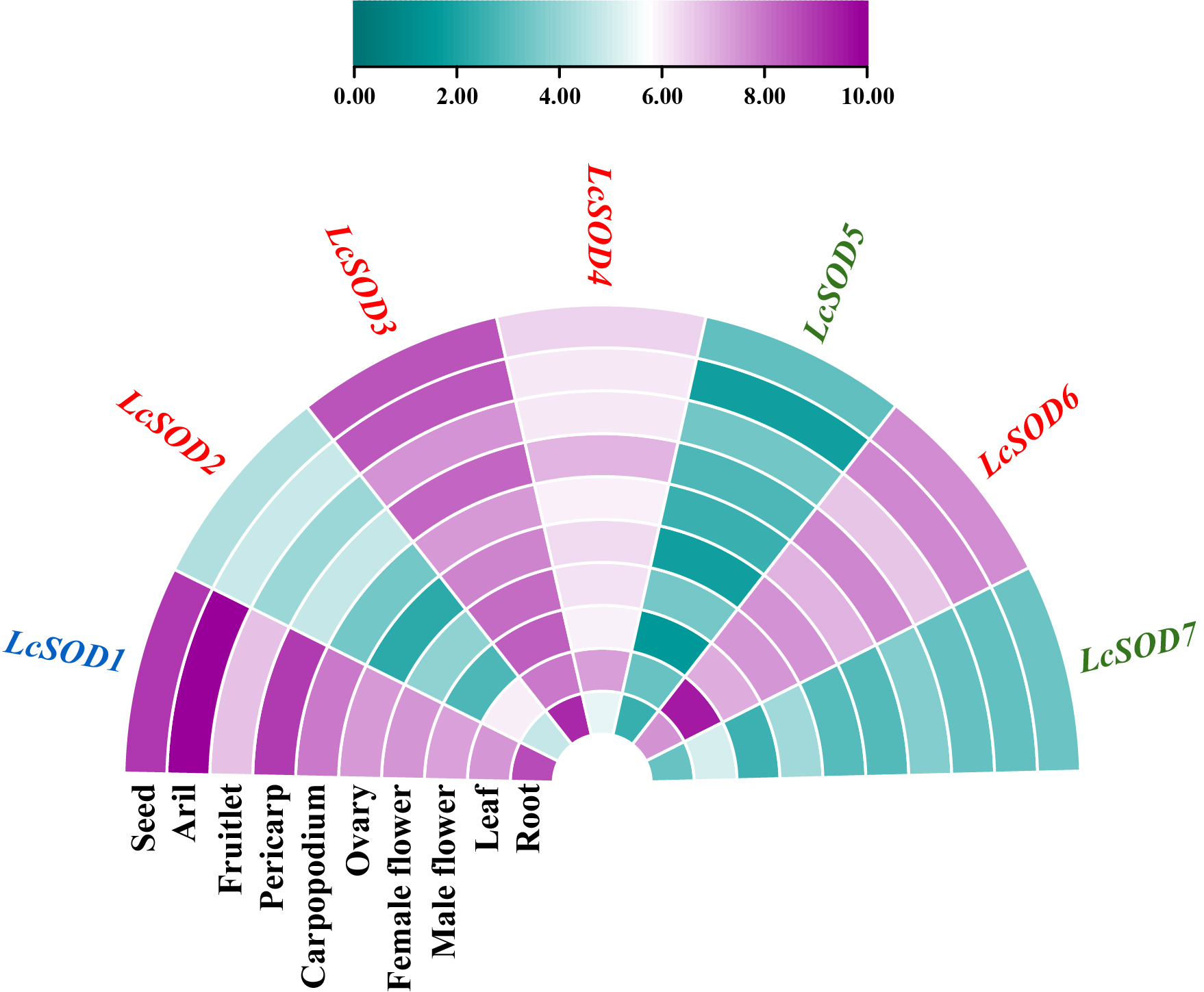

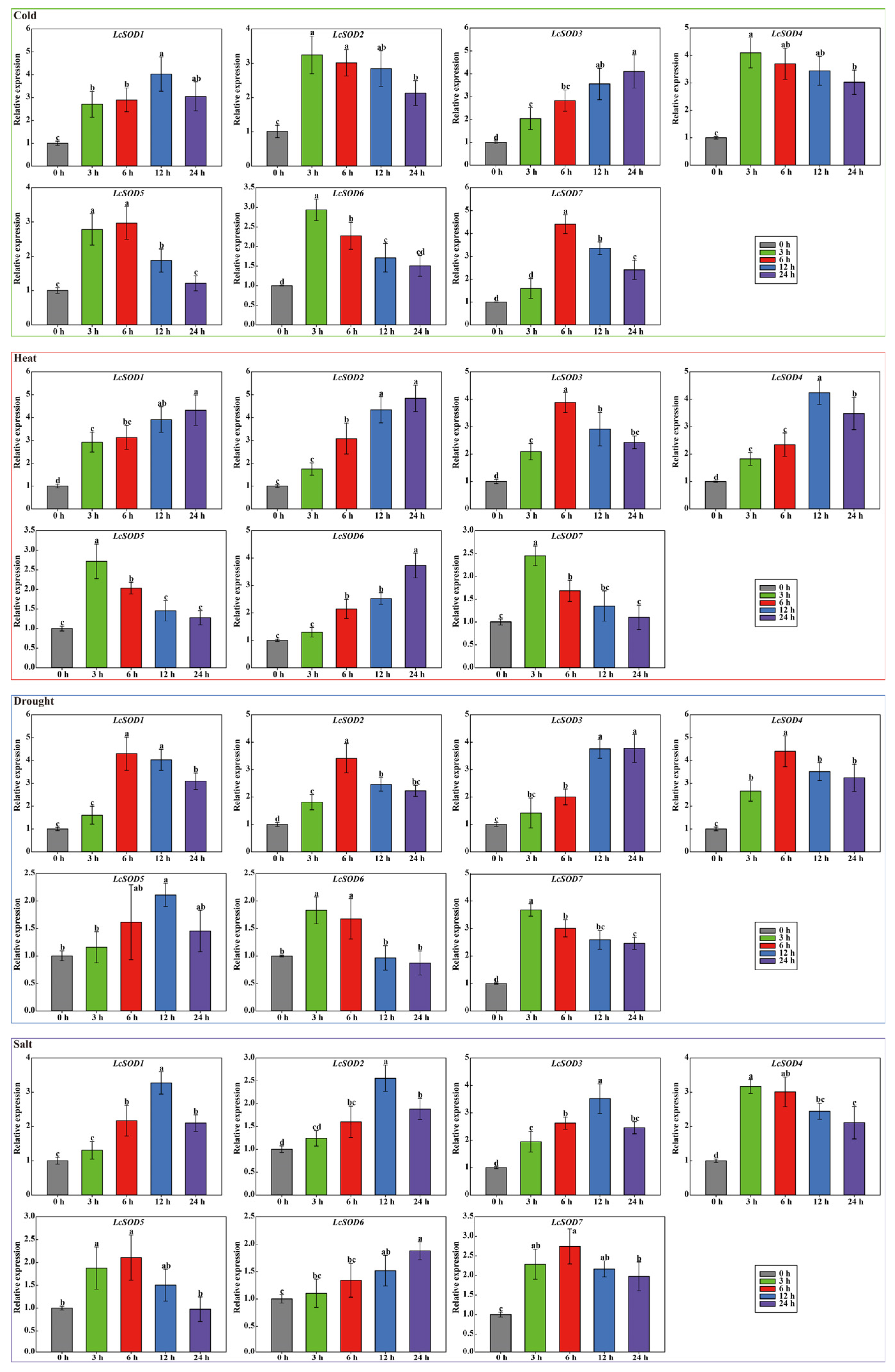

3.7. Expression Profiles of the LcSOD Genes in Various Tissues and Their Responses to Abiotic Stresses

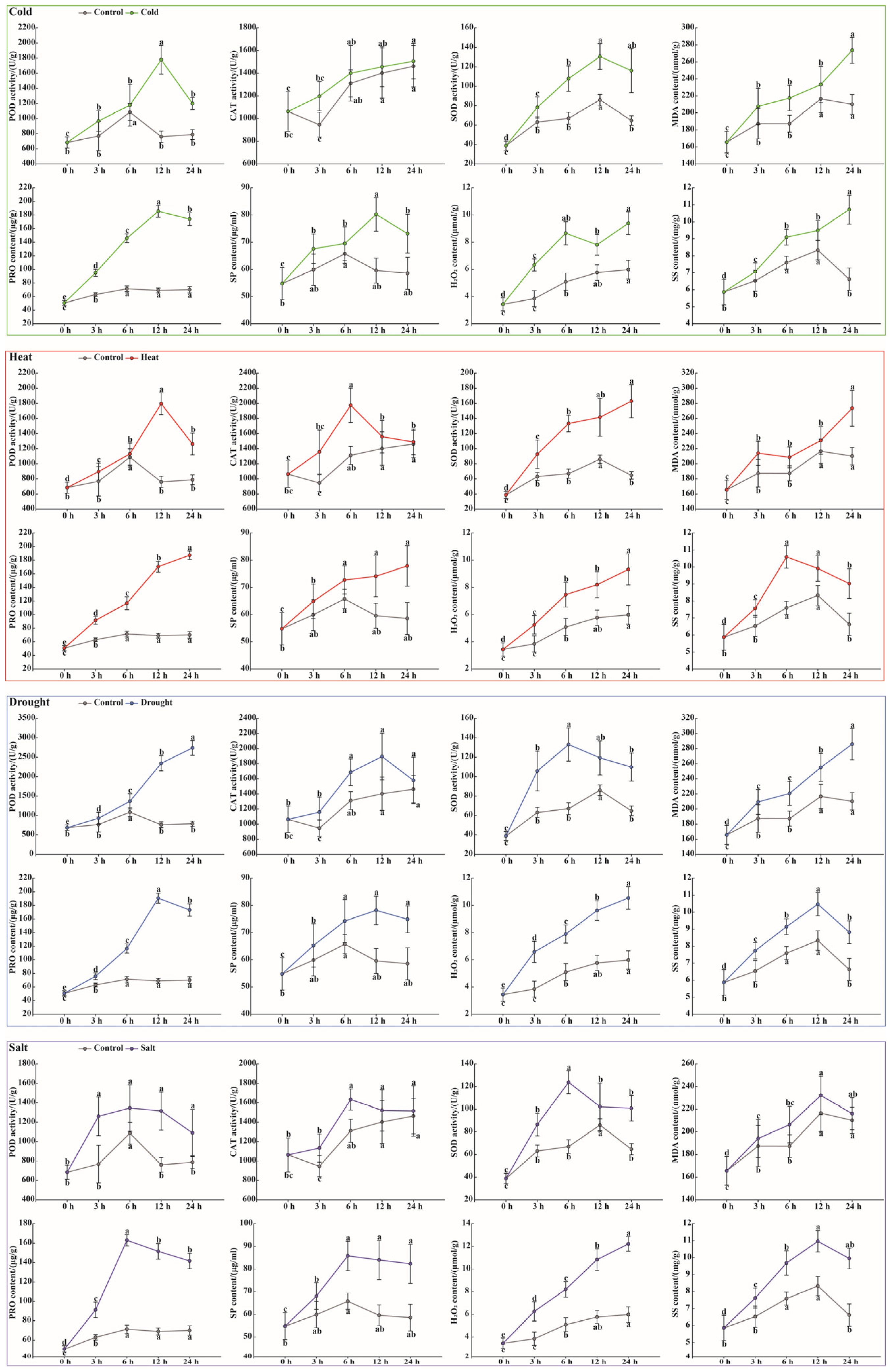

3.8. Physiological Responses of Litchi Leaves to Abiotic Stresses

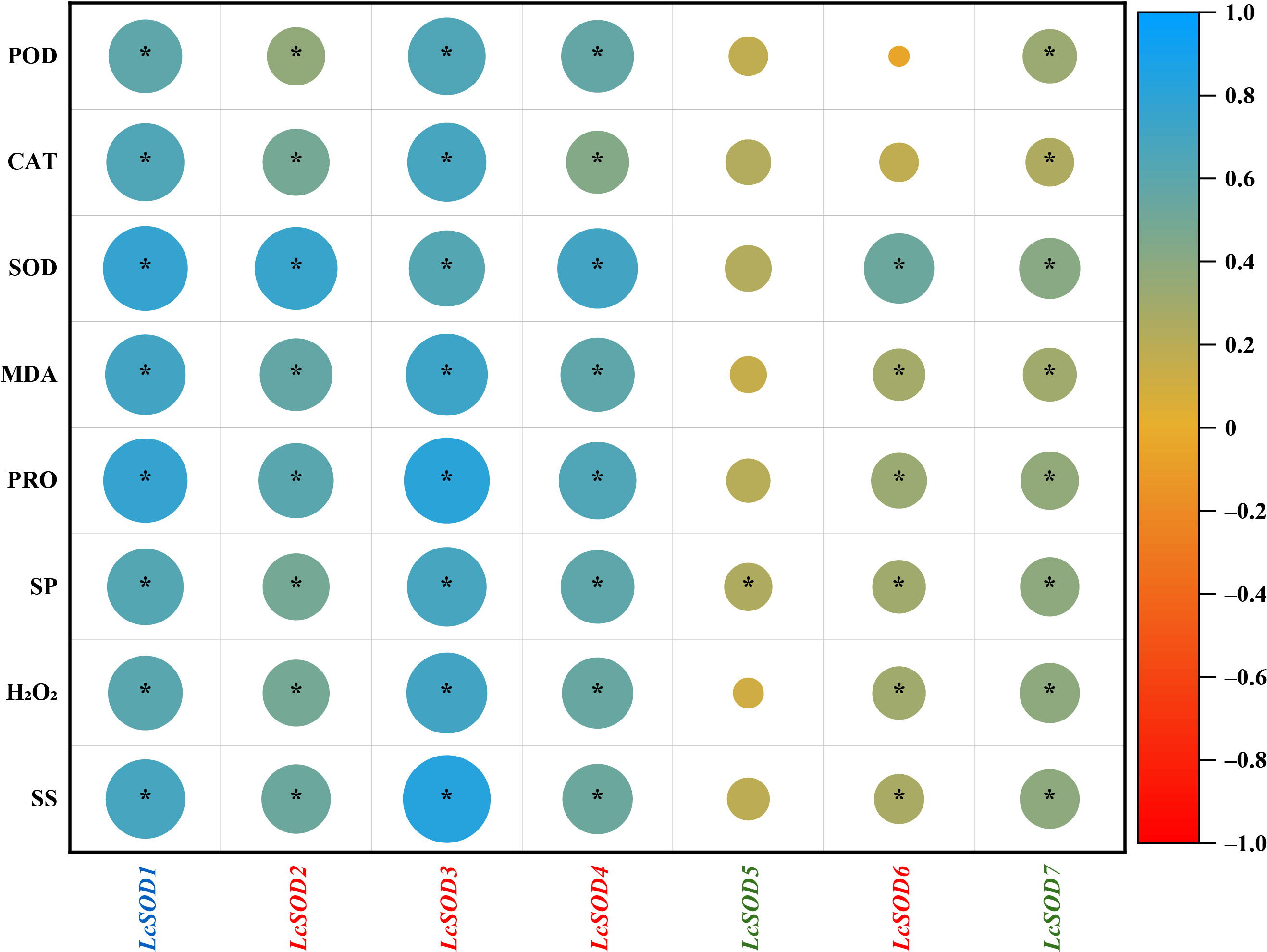

3.9. Correlations Between the LcSOD Gene Expression Levels and Physiological Parameters of Litchi Leaves to Abiotic Stresses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, P.; Zhu, J.K. Plant water stress sensing: Osmosensors start to make sense. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 1896–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, R.; Kumari, P.; Chatrath, A.; Prasad, R. Characterisation of recombinant thermostable manganese-superoxide dismutase (NeMnSOD) from Nerium oleander. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 3251–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Wani, O.A.; Lone, J.K.; Manhas, S.; Kour, N.; Alam, P.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, P. Reactive oxygen species in plants: From source to sink. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, C.; Carvalho, M.E.A.; Azevedo, R.A.; Fidalgo, F. Plants facing oxidative challenges—A little help from the antioxidant networks. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 161, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, R.; Fatima, K.; Azeem, F.; ALgwaiz, H.I.M.; Sadaqat, M.; Rasheed, A.; Batool, R.; Shah, A.N.; Zaynab, M.; Shah, A.A.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes in Daucus carota: Novel insights into structure, expression, and binding interaction with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) under abiotic stress condition. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 870241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Yang, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Ma, D.; Yin, J. Genome-wide identification and transcriptional expression analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD) family in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Peer J. 2019, 7, e8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Lai, Z.-X. Superoxide dismutase multigene family in longan somatic embryos: A comparison of CuZn-SOD, Fe-SOD, and Mn-SOD gene structure, splicing, phylogeny, and expression. Mol. Breed. 2013, 32, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Abreu, I.A.; Cabelli, D.E.; Maroney, M.J.; Miller, A.-F.; Teixeira, M.; Valentine, J.S. Superoxide dismutases and superoxide reductases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3854–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Deng, F.; Yuan, R.; Shen, F. Genome-wide characterization and expression analyses of superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, D.; Lakhanpal, N.; Singh, K. Genome-wide identification and characterization of abiotic-stress responsive SOD (superoxide dismutase) gene family in Brassica juncea and B. rapa. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliebenstein, D.J.; Monde, R.A.; Last, R.L. Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis: An eclectic enzyme family with disparate regulation and protein localization. Plant Physiol. 1998, 118, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraya, T.; Mori, T.; Maruyama, T.; Sasaki, M.; Takamatsu, T.; Oikawa, K.; Itoh, K.; Kaneko, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Mitsui, T. Golgi/plastid-type manganese superoxide dismutase involved in heat-stress tolerance during grain filling of rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lai, Z.; Lin, Y.; Lai, G.; Lian, C. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the superoxide dismutase gene family in Musa acuminate cv. Tianbaojiao (AAA group). BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaouthar, F.; Ameny, F.K.; Yosra, K.; Walid, S.; Ali, G.; Faiçal, B. Responses of transgenic Arabidopsis plants and recombinant yeast cells expressing a novel durum wheat manganese superoxide dismutase TdMnSOD to various abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 198, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Hao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lu, L.; Shi, J.; Chen, J. The identification and expression analysis of the Liriodendron chinense (Hemsl.) Sarg. SOD gene family. Forests 2023, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Shao, L.; Luo, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J. Identification and analysis of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family and potential roles in high-temperature stress response of herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Liu, W.; Fan, C. Genome-wide identification, phylogenetic investigation and abiotic stress responses analysis of the PP2C gene family in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1547526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, W.; Fan, C. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the class III peroxidase gene family under abiotic stresses in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5804, Erratum in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, F.; Feng, J.; Liu, B.; Mai, Y.; Chu, X.; Wei, W.; Li, X.; et al. SapBase: A central portal for functional and comparative genomics of Sapindaceae species. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Z.; Hu, F.C.; Hu, G.B.; Li, X.J.; Huang, X.M.; Wang, H.C. Differential expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in relation to anthocyanin accumulation in the pericarp of Litchi Chinensis Sonn. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, M.; Aleem, S.; Sharif, I.; Wu, Z.; Aleem, M.; Tahir, A.; Atif, R.M.; Cheema, H.M.N.; Shakeel, A.; Lei, S.; et al. Characterization of SOD and GPX gene families in the soybeans in response to drought and salinity stresses. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 460, Erratum in Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, D.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Ling, H.; Huang, N.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; et al. A comprehensive identification and expression analysis of VQ motif-containing proteins in sugarcane (Saccharum spontaneum L.) under phytohormone treatment and cold stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, J. Genome-Wide Identification and analysis of the VQ motif-containing protein family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 28683–28704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xue, D. Genome-wide identification of the SOD gene family and expression analysis under drought and salt stress in barley. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 94, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Lin, S.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, S.; Liu, N. Genome-wide identification of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in Cymbidium species and functional analysis of CsSODs under salt stress in Cymbidium sinense. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, R.; Shang, S.; Tang, X. Genome-wide analysis of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in Zostera marina and expression profile analysis under temperature stress. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; He, L.; Yu, T.; Ji, X.; Li, R.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H.; Liu, W. The superoxide dismutase gene family in Nicotiana tabacum: Genome-wide identification, characterization, expression profiling and functional analysis in response to heavy metal stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 904105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Raza, A.; Gao, A.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hussain, M.A.; Mehmood, S.S.; Cheng, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zou, X. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) under different hormones and abiotic stress conditions. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Song, H.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Guo, R.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.). 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.M.; Hua, W.P.; Cao, X.Y.; Yan, J.A.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Gene 2020, 742, 144603, Erratum in Gene 2020, 742, 144639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zeng, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. In silico identification and expression analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in Medicago truncatula. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Hu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, W.; Wu, T.; Du, X. Rice OsWRKY50 mediates ABA-dependent seed germination and seedling growth, and ABA-independent salt stress tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Fan, R.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wai, M.H.; Yang, Q.; Su, H.; Liu, K.; Ma, S.; Chen, Z.; et al. GmbZIP152, a soybean bZIP transcription factor, confers multiple biotic and abiotic stress responses in plant. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, S.; Lee, G.; Kang, M.; Park, K.; Park, E.; Lee, S.; Song, J.; Goldberg, J.K.; Baldwin, I.T.; Joo, Y.; et al. MYC2 and MYC3 orchestrate pith lignification to defend Nicotiana attenuata stems against a stem-boring weevil. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 2425–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Kong, G.; Chao, J.; Yin, T.; Tian, H.; Ya, H.; He, L.; Zhang, H. Genome-wide identification of the rubber tree superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family and analysis of its expression under abiotic stress. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Hamidou, A.A.; Zhao, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Lin, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, K.; Chen, Y. Superoxide dismutase gene family in cassava revealed their involvement in environmental stress via genome-wide analysis. iScience 2023, 26, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of MIKC-type MADS-box gene family in Punica granatum L. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zi, Y.; Rong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Nie, L.; Wang, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Expression analysis of the ABF gene family in Actinidia chinensis under drought stress and the response mechanism to abscisic acid. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.N.; Pauwels, L.; Goossens, A. The ubiquitin system and jasmonate signaling. Plant 2016, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, C.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Lin, Y.; Lai, Z.; Guo, Y. Genome-wide investigation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family and their regulatory miRNAs reveal the involvement in abiotic stress and hormone response in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.H.; Zhu, L.C.; Xu, Y.; Lü, L.; Li, X.G.; Li, W.H.; Liu, W.D.; Ma, F.W.; Li, M.J.; Han, D.G. Genome-wide identification and function analysis of the sucrose phosphate synthase MdSPS gene family in apple. J. Integr. Agr. 2023, 22, 2080–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Liu, W. The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) Gene Family in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): Identification, Classification, and Expression Responses in Leaves Under Abiotic Stresses. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010014

Fan C, Yang J, Chen R, Liu W. The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) Gene Family in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): Identification, Classification, and Expression Responses in Leaves Under Abiotic Stresses. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Chao, Jie Yang, Rong Chen, and Wei Liu. 2026. "The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) Gene Family in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): Identification, Classification, and Expression Responses in Leaves Under Abiotic Stresses" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010014

APA StyleFan, C., Yang, J., Chen, R., & Liu, W. (2026). The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) Gene Family in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): Identification, Classification, and Expression Responses in Leaves Under Abiotic Stresses. Antioxidants, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010014