1. Introduction

Early weaning of lambs in intensive production systems can increase ewe reproductive efficiency and productivity while reducing feeding costs [

1]. However, in practical flock management, diarrhea remains a major and persistent challenge that severely compromises production efficiency and economic returns [

2]. This is particularly evident during the first two weeks after birth and after weaning, when the risk of diarrhea-associated mortality in lambs is markedly increased [

3]. In early life, the immaturity of the immune system and the incomplete establishment of a stable intestinal microbiota render the lamb gut more susceptible to pathogenic invasion, thereby predisposing to diarrhea. Weaning is also accompanied by pronounced physiological and environmental stress; during this period, lambs experience multiple challenges, including changes in social grouping and alterations in diet composition and physical form [

4], which increase intestinal exposure to pathogens and raise the risk of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated damage to intestinal tissues [

5,

6]. Excessive ROS can induce DNA damage, protein aggregation, and dysfunction of cell membranes, ultimately leading to injury and apoptosis of gastrointestinal epithelial cells [

7]. When the accumulation of ROS in the intestine exceeds the antioxidant defense capacity of the host, the resulting imbalance triggers oxidative stress [

8]. Intestinal oxidative stress further promotes inflammation, impairs barrier function, and alters intestinal architecture [

9,

10], ultimately leading to a higher incidence of diarrhea and impaired growth and development. Therefore, alleviating intestinal oxidative stress during the weaning period and preserving the structural and functional integrity of the gut are critical for mitigating weaning stress and reducing the risk of diarrhea in lambs.

The intestine is not only the primary site for digestion and nutrient absorption but also the largest immune organ of the body [

11]. Tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells form the first mechanical barrier, limiting the entry of pathogens and toxins into the circulation. Studies have shown that early weaning markedly reduces the expression of tight junction proteins such as zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-1, thereby compromising intestinal barrier function [

12]. Furthermore, Li et al. (2018) reported that alterations in the expression of genes related to intestinal barrier function in lambs can persist for up to 84 days during the weaning period [

13], indicating that weaning stress exerts long-lasting effects on the intestinal barrier. Mucins secreted by goblet cells together with antimicrobial proteins produced by epithelial cells form the intestinal mucus layer [

14]. This mucus layer prevents pathogens from colonizing the intestinal surface [

15]. Weaning stress induces crypt hyperplasia and goblet cell loss in the colon, thereby disrupting the integrity of the mucus barrier [

16]. Intestinal epithelial cells can also directly recognize both pathogenic and beneficial microorganisms and orchestrate immune responses, primarily through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [

17]. Evidence from early-weaned goats demonstrates that signaling pathways involved in chemokine signaling, IL-17 signaling, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) activation are upregulated in the colonic mucosa, reflecting alterations in mucosal immune status [

12]. In addition, the intestinal epithelium transports immunoglobulin A (IgA) into the lumen via the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) and responds to biological stress by secreting antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, and chemokines [

18]. After weaning, mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α increases in the jejunum and colon, whereas IL-10 expression decreases [

19], suggesting an enhanced pro-inflammatory response and attenuated anti-inflammatory regulation. Cui et al. (2018) observed that, even on day 15 after weaning, the expression of proteins involved in immune processes remained significantly downregulated in the jejunal epithelium of lambs [

20], further indicating that weaning stress has medium- to long-term effects on intestinal immune function.

As an important alternative to antibiotic therapy for intestinal inflammation, microecological preparations act by activating the intestinal immune system, promoting intestinal development, and alleviating oxidative stress, thereby reducing the incidence of diarrhea and supporting host growth and development. Probiotics have been shown to exert beneficial effects on intestinal health during the weaning period. Studies indicate that probiotics can improve intestinal barrier function and enhance antioxidant capacity through multiple mechanisms, thereby effectively reducing the occurrence of diarrhea [

21,

22]. On the one hand, probiotics modulate gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) to initiate and regulate the host innate and adaptive immune responses. For example, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species can induce dendritic cells to produce the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and suppress the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ, thereby attenuating intestinal inflammatory responses [

23,

24]. On the other hand, probiotics can also modulate the immune function of intestinal B cells, promoting the secretion of IgA and other antibodies and thereby strengthening the defensive capacity of the intestinal mucosal barrier [

25,

26]. In addition, the antioxidant properties of probiotics represent another important mechanism by which they alleviate intestinal stress. Relevant studies have shown that probiotics can modulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes, thereby reducing oxidative stress–induced damage to intestinal tissues and consequently decreasing oxidative injury and apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells [

5,

27].

Despite the widely recognized beneficial effects of probiotics, the synergistic actions among different strains and their combinations, as well as the precise mechanisms by which they act in sheep, remain to be fully elucidated. Therefore, to determine whether the sheep-derived probiotic strains previously isolated in our laboratory can alleviate diarrhea by improving intestinal health, we conducted a study in early-weaned lambs. Specifically, we systematically evaluated the regulatory effects of a sheep-derived probiotic mixture on intestinal immune function, barrier integrity, and antioxidant capacity, and further assessed its efficacy in reducing the incidence of diarrhea and promoting growth and development in lambs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethical Statement

This experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shihezi University (approval date: 5 June 2024; approval code: A2024-428). The experiment was conducted at Shangpin Meiyang Co., Ltd., Changji, China.

2.2. Animals and Diets

In this experiment, 60 healthy newborn Hu sheep lambs (1 d of age) were enrolled. All lambs were dam-suckled and had ad libitum access to pelleted feed and water. Lambs were randomly allocated to three groups. Lambs in the control group (CON) were continuously suckled until 35 d of age. The remaining two groups were weaned at 30 d of age and reared until 35 d of age, when lambs were humanely euthanized for sample collection. Among the weaned lambs, those that did not receive any supplements were assigned to the early-weaning group (EW). Lambs in the early-weaning plus probiotic group (EWP) received daily oral supplementation with

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M1 and

Limosilactobacillus reuteri K4, both isolated from sheep in our laboratory, at a concentration of 1 × 10

9 CFU/g and an administration amount of 2 g/day (i.e., 2 × 10

9 CFU per lamb per day) from 1 day of age until weaning. Multistrain probiotics are increasingly adopted in commercial livestock production systems owing to their enhanced functional stability and synergistic benefits compared with single-strain formulations, we evaluated a sheep-derived mixed formulation (

L. plantarum M1 +

L. reuteri K4) as a practical intervention against early-weaning stress. All lambs had ad libitum access to creep feed from 7 d of age. The ingredient composition and nutrient levels of the diet are shown in

Table S1.

During the experimental period, diarrhea was monitored daily, and diarrhea scores and incidence were calculated (

Table S2) [

28]. A daily score of ≥3 was classified as diarrhea according to a standardized protocol. Feed intake was recorded daily, and lambs were weighed once every two weeks before the morning feeding to calculate growth performance. The incidence of diarrhea in lambs was calculated as follows: incidence of diarrhea (%) = (number of diarrheic lambs in each group × days with diarrhea)/(total number of lambs in each group × experimental days) × 100.

2.3. Sample Collection

On day 35 of the experiment, jugular blood was collected from six lambs in each group before the morning feeding using a disposable blood collection needle and two 10 mL heparinized gel vacuum tubes. After resting for 20 min, the blood samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000× g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was aliquoted into 2 mL centrifuge tubes and stored in liquid nitrogen for subsequent determination of biochemical, antioxidant, and immunological parameters.

On the last day of the experiment, six lambs from each group were randomly selected and transferred to a slaughterhouse for euthanasia. Immediately after slaughter, the intestinal tract and visceral organs were removed. Subsequently, segments of the jejunum, ileum, and colon were rapidly placed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and fixed. Another portion of colonic tissue was placed in 2 mL cryovials and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen for transcriptomic analysis.

2.4. Biochemical Assays

Colonic tissues were homogenized in pre-cooled saline to obtain 10% (w/v) tissue homogenates, which were then centrifuged, and the supernatants were collected. Plasma levels of glucose (GLU), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), globulin (GLB), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), indirect bilirubin (IBIL), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) were measured using a fully automated biochemical analyzer. Colonic and plasma activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), as well as malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations, were determined using commercial biochemical reagent kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China). Colonic and plasma concentrations of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin G (IgG), and immunoglobulin M (IgM), as well as colonic secretory IgA (sIgA), were quantified using ELISA kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China). Colonic levels of mucin 2 (MUC2), occludin, claudin-1, zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and diamine oxidase (DAO) were also quantified using ELISA kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

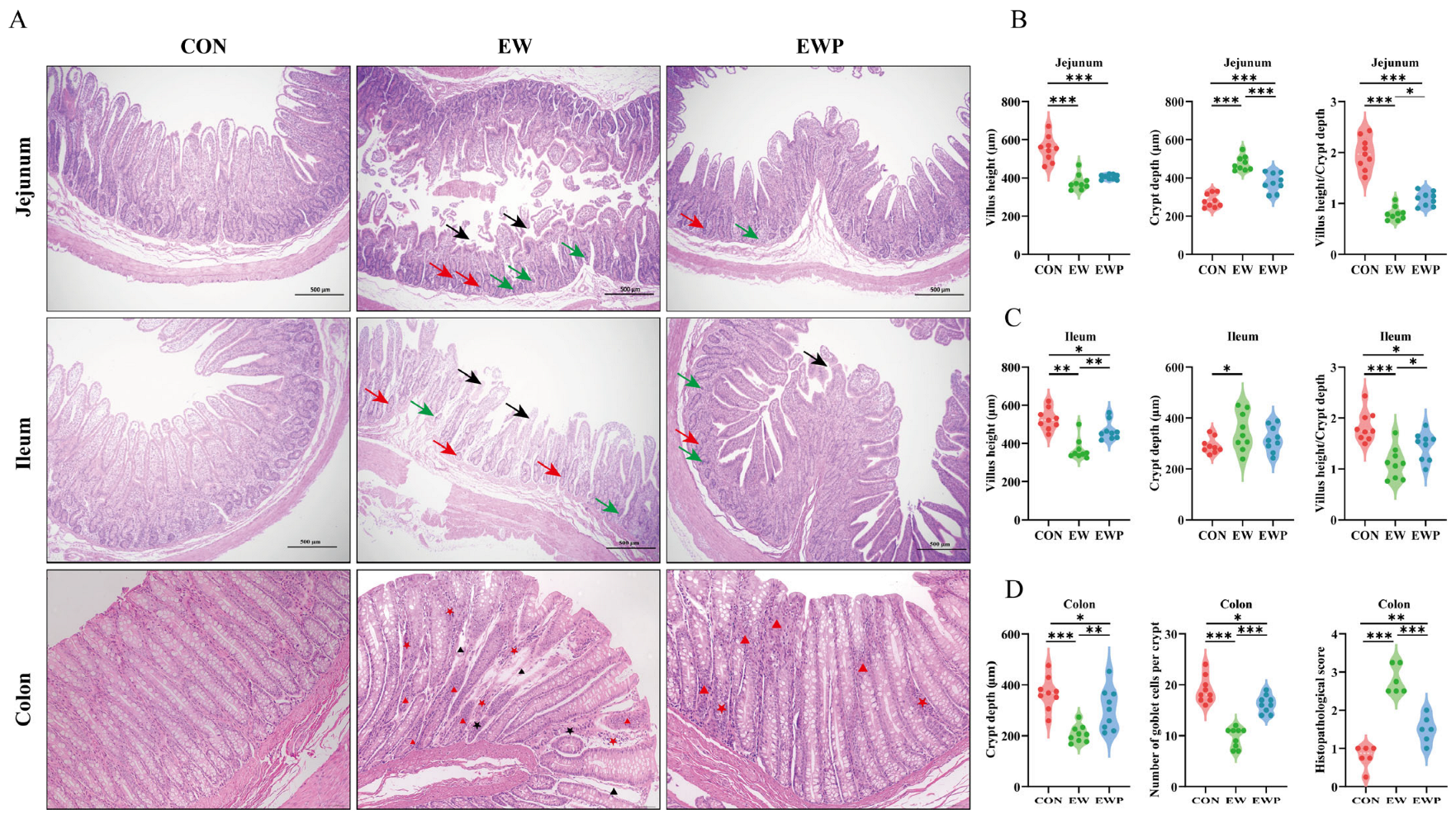

2.5. Histological Analysis

The tissues were stored in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, followed by dehydration through graded ethanol. Tissue sections (5 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). At the same time, the depth of crypts in colon tissue and the average number of goblet cells per colon crypt, as well as the villus height and crypt depth in the duodenum and jejunum, were measured using ImageJ v1.8.0 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Transcriptomic Analysis of Colon

Total RNA was extracted from colonic tissue using TRIzol reagent (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan). RNA integrity was assessed using a 5300 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and RNA concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). High-quality RNA was used to construct sequencing libraries, which were sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (PE150) at Shanghai Majorbio Biopharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DESeq2. Genes with |fold change| > 2 and Benjamini–Hochberg FDR-adjusted

p-values (padj) < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using topGO (Gene Ontology Consortium,

http://geneontology.org/). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was used to analyze DEGs involved in major biochemical metabolic and signaling pathways (

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/, accessed on 10 December 2025). Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to characterize gene association patterns across samples and to identify co-expressed gene modules, as well as to explore associations between gene modules and phenotypes of interest, and hub genes within each module (

https://horvath.genetics.ucla.edu/html/CoexpressionNetwork/Rpackages/WGCNA/faq.html, accessed on 10 December 2025). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of hub genes (grouped according to median expression level) was performed using the clusterProfiler package (v4.18.4). Hub genes were further prioritized using the MCC algorithm implemented in the CytoHubba plugin (v0.1).

2.7. Validation of RNA-Seq

Total RNA from colonic tissue was extracted using a TRIzol reagent kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), quantified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Waltham, MA, USA), and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The resulting cDNA was stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was then performed on a Roche LightCycler 96 system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using 1 µL of a 1:20 diluted cDNA sample as the template for each reaction. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method, with β-actin serving as the internal reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in

Supplementary Table S3.

2.8. Statistics and Analysis

All experimental data were first entered into Microsoft Excel 2024 for organization and then imported into SPSS 27.0 Statistics (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. Data on lamb body weight, feed intake, fecal score, and incidence of diarrhea were analyzed using a general linear model, with the effect of Hu sheep specified as a random effect and diet and time specified as fixed effects. The diet × time interaction was also included in the model. For parameters related to intestinal tissue samples, mRNA expression, plasma biochemical indices, and antioxidant capacity, the individual sheep was considered the experimental unit. These variables were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and differences among means were assessed using the least significant difference (LSD) test in SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 19.0; IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). All data are expressed as means ± SEMs. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In early life, lambs rely on passive immunity acquired from colostrum. When this passive transfer is inadequate, their resistance to environmental pathogens is reduced, predisposing them to diarrhea. In addition, changes in diet composition and separation from the dam after weaning further increase diarrhea risk in lambs [

29,

30]. Diarrhea impairs the digestion and absorption of nutrients, leading to growth retardation and thereby compromising subsequent growth and reproductive performance [

31,

32]. Although antibiotic therapy is currently one of the most effective strategies for controlling diarrhea, antibiotic residues and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance pose serious threats to animal and public health. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop safe, “green” microbial alternatives to antibiotics that can reduce the incidence of diarrhea and promote intestinal health, which has become a major goal of modern animal husbandry [

33]. Beyond probiotics, other nutritional strategies, such as liquid whey supplements, have been reported to modulate intestinal histology and immune-inflammatory responses during weaning stress in pigs [

34,

35], suggesting that targeted nutrition can enhance gut mucosal defense during the early life transition. We acknowledge that the absence of single-strain groups limits strain-specific attribution; future studies will compare single strains and their combination to quantify additive versus synergistic effects. In this context, we investigated the preventive effect of dietary supplementation with a mixture of the probiotic strains

L. plantarum M1 and

L. reuteri K4 on weaning-induced diarrhea in lambs. Furthermore, by combining analyses of intestinal morphology with transcriptomic profiling, we explored the mechanisms underlying the interaction between intestinal health and systemic immunity.

Building on this background, previous studies have shown that weaning stress reduces feed intake and increases the incidence of diarrhea in lambs [

36], thereby restricting their growth and development [

37,

38]. Consistent with these reports, our results showed that weaning significantly reduced feed efficiency and increased diarrhea incidence, leading to decreases in both body weight and average daily gain in weaned lambs [

39]. Probiotic supplementation reduced the incidence of diarrhea to a level comparable to that observed in continuously suckled control lambs. Weaning also induced pronounced metabolic and immune alterations. Early weaning significantly decreased serum TP and GLB concentrations, indicating impaired protein synthesis and/or increased protein catabolism [

40,

41]. In addition, lipid metabolism markers, TG, TC, and HDL, were simultaneously reduced, consistent with the concept that weaning stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and promotes protein and fat mobilization to meet increased energy demands [

42,

43].

In line with these systemic changes, cytokines with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties are key components of cell-mediated immunity [

44]. In the present study, plasma IL-1β and TNF-α levels were elevated, whereas IL-10 and TGF-β levels were reduced, indicating that early weaning induced a systemic pro-inflammatory state. The increased concentrations of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgM, IgG) in early-weaned lambs likely reflect compensatory immune activation in response to enhanced antigen exposure caused by impaired intestinal barrier function [

40,

45]. Supplementation with the mixed probiotics partially reversed the elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines and immunoglobulins. Weaning stress is also known to generate excessive free radicals and trigger oxidative stress [

30]. In this study, we showed that dietary supplementation with the mixed probiotics conferred marked antioxidant benefits, as evidenced by a significant reduction in plasma MDA, a lipid peroxidation product, and increased activities of the antioxidant enzymes CAT and GSH-Px. Collectively, these findings suggest that the probiotics may alleviate weaning-induced growth retardation and increased diarrhea by modulating intestinal inflammatory signaling, enhancing intestinal barrier integrity, and attenuating systemic oxidative stress.

At the intestinal structural level, damage to intestinal morphology severely impairs the digestion and absorption of nutrients [

46]. The intestinal barrier maintains gut health by preventing pathogens, toxins, and antigens from crossing the intestinal mucosa into the bloodstream [

47]. Intestinal histomorphology has been widely used to assess the development and renewal of intestinal epithelial cells [

48]. In general, increased villus height enlarges the absorptive surface area of the small intestine, whereas reduced crypt depth and a higher villus height-to-crypt depth ratio (VH/CD) indicate slower epithelial turnover and more mature enterocytes, which are associated with improved nutrient absorption and growth performance [

49,

50]. Our results showed pronounced villus atrophy and a reduced villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in the jejunum and ileum of weaned lambs, corroborating the decreases in feed efficiency and body weight after weaning. Previous studies have demonstrated that supplementation with

L. reuteri L81 and

L. johnsonii M5 significantly increases villus height, decreases crypt depth, and consequently increases the villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in calves and lambs [

27,

51], which is consistent with our findings. Tight junctions, which are composed of transmembrane proteins such as claudins and occludins together with scaffold proteins (e.g., ZO family proteins), are responsible for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier and regulating intestinal permeability [

52]. In addition, MUC2 secreted by goblet cells is the major structural component of the colonic mucus layer and is crucial for maintaining epithelial barrier integrity, blocking bacteria and toxins, and preventing colitis [

53]. Supplementation with mixed probiotics attenuated the weaning-induced reduction in colonic goblet cell numbers and the increase in histopathological scores, and significantly upregulated the levels of tight junction proteins and MUC2. Consistent with previous findings, supplementation with sheep-derived

C. beijerinckii R8 and bovine-derived

L. reuteri L81 markedly increased both the protein abundance and gene expression of tight junction components in the colon and jejunum [

2,

51].

Diarrhea is commonly accompanied by intestinal inflammation and redox imbalance within the gut [

54,

55]. There is evidence that the hindgut microbiota of early-weaned goats promotes the expression of inflammatory cytokines [

12], and that disturbed intestinal redox homeostasis further stimulates immune responses [

54]. Probiotics can modulate cytokine expression and reduce inflammation, thereby activating and shaping host immune responses [

56]. In accordance with previous studies, supplementation with mixed probiotics reduced the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, while increasing the levels of the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10 and TGF-β [

27,

57]. In weaned lambs, elevated intestinal LPS concentrations together with reduced DAO levels indicate impaired intestinal barrier integrity [

30,

58]. Damage to both the epithelial and mucus barriers increases the luminal antigen load and facilitates the translocation of bacteria and LPS into the mucus layer, which excessively stimulates B-cell activation and antibody production [

59,

60], leading to increased concentrations of sIgA, IgA, IgM, and IgG in plasma and mucosa. Probiotic supplementation improved intestinal morphology and tight junction protein expression, attenuated local and systemic inflammation, and consequently reduced antigenic pressure, thereby restoring mucosal immunoglobulin levels toward homeostatic values [

61]. Weaning-induced oxidative stress may arise from excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by inflammatory cells [

62], mitochondrial dysfunction [

63], and insufficient dietary antioxidants [

64]. In our experiment, probiotic supplementation effectively enhanced intestinal antioxidant enzyme activities and reduced lipid peroxidation, indicating that mixed probiotics stimulate endogenous antioxidant defenses or directly scavenge ROS through bacterial antioxidant enzymes [

65].

Transcriptomic analysis provides molecular-level insights into weaning-induced intestinal dysfunction and the mechanisms underlying probiotic-mediated protection. The study by Zhang et al. demonstrated that early weaning modulates host intestinal immune responses by altering the colonic epithelial transcriptional profile in lambs [

12]. Consistent with these findings, our data showed that early weaning upregulated genes associated with immune system processes and inflammatory responses, while downregulating genes involved in cellular metabolism and developmental processes. KEGG pathway analysis further revealed significant enrichment of cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, NF-κB signaling, TNF signaling, IL-17 signaling, Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation, and inflammatory bowel disease pathways. These findings indicate that early weaning activates both innate and adaptive immune pathways in the colonic mucosa, which is consistent with our phenotypic observations of elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and immunoglobulins in the intestines of weaned lambs. Similar activation of NF-κB, TNF, and IL-17 related pathways has also been reported in the intestines of other weaning stress models and is considered a key driver of mucosal inflammation and barrier disruption [

66,

67]. Probiotic supplementation suppressed these excessively activated pathways. Previous studies have shown that lactic acid bacteria can downregulate NF-κB dependent inflammatory gene expression, reduce Th1/Th17 polarization, and promote a more balanced mucosal immune response in the immature intestine [

68,

69]. In addition to suppressing classical inflammatory pathways, probiotic supplementation markedly upregulated the PPAR signaling pathway. Activation of PPARα/γ not only coordinates lipid and energy metabolism but also exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB and AP-1 driven transcription of inflammatory genes [

70,

71]. PPAR signaling was identified primarily at the transcript level. While these findings are consistent with PPAR-mediated anti-inflammatory regulation, we did not quantify PPAR proteins or phosphorylation states in the current cohort. Future work will include protein-level validation.

WGCNA identified several gene modules that were positively correlated with early weaning and negatively correlated with probiotic supplementation. The pathways enriched in these modules respond to increased antigenic and bacterial translocation, thereby enhancing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and driving a shift of the colon toward a Th1/Th17-type immune response. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by excessive and uncontrolled immune responses mediated by Th1, Th2, or Th17 cells and their associated cytokines [

72]. Hub genes within these modules, such as

IFNG, are linked to Th1 cells in colitis, and Th1 cells promote cell-mediated inflammatory responses by inducing the activation of macrophages, NK cells, B cells, and CD8

+ T cells [

73]. Increased LPS levels in intestinal tissues engage membrane receptors, thereby enhancing NF-κB signaling and the secretion of the inflammatory mediator TNF-α, which in turn promotes the accumulation of immune cells in the tissue and causes tissue damage [

74]. Consistent with previous clinical observations, patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis exhibit marked accumulation of IL-17-producing Th17 cells and increased IL-23 expression in the intestinal mucosa [

75]. Previous studies have also highlighted IFN-γ, IL-17A/F, and IL-22 as key effector cytokines that drive epithelial damage and increased permeability in IBD and infection models [

76]. Probiotics have been shown to downregulate these cytokines and preserve epithelial integrity [

77,

78,

79], which is consistent with our observations on intestinal barrier function. Our data support the notion that activation of the IL-23/Th17 axis is a central feature of intestinal inflammation. The downregulation of Th17-related genes by probiotic supplementation suggests that beneficial bacteria may modulate adaptive immune responses to prevent excessive inflammation.

Network-level analyses further support the concept that probiotics target key regulatory nodes controlling immune responses in the colon. PPI network analysis showed that hub genes such as

IFNG,

IL17A,

IL1B,

IL22, and

TBX21 occupy highly connected central positions, indicating that they play pivotal roles in coordinating inflammatory responses and represent potential therapeutic targets for alleviating weaning-induced intestinal inflammation. Previous studies have demonstrated that blocking receptors for Th17-associated pro-inflammatory cytokines can be used to treat IBD [

80]. Consistent with our findings,

L. reuteri ZY15 alleviates colitis by downregulating IL-17 and TNF-α [

69]. In addition, oral administration of an engineered

Lactobacillus strain that simultaneously targets IL-17A, IL-23, and TNF-α exerts synergistic effects in the treatment of IBD [

81]. The marked upregulation of PPAR pathway components such as

FABP1,

RXRG,

CRABP1,

CRABP2, and

HMGCS2 suggests that probiotic intervention not only attenuates inflammatory responses but also remodels lipid and vitamin A metabolic programs in colonic epithelial cells. Vitamin A plays a key regulatory role in mucosal immunity by promoting the generation of Foxp3

+ regulatory T cells and IgA production through retinoic acid signaling, while modulating dendritic cell function and guiding the differentiation and mucosal homing of effector T cells, thereby strengthening the mucosal barrier and immune protection [

82]. Supplementation with vitamin-producing probiotic strains can also ameliorate IBD [

83], further supporting the notion that probiotics promote restoration of mucosal homeostasis by improving the metabolic status of the epithelium.

In this addition, we elucidate the potential complementary mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of

L. plantarum M1 and

L. reuteri K4.

L. plantarum M1 contributes to antioxidant defense and barrier reinforcement likely through exopolysaccharide production and organic acid secretion, while

L. reuteri K4 enhances immune modulation and pathogen inhibition via reuterin production and biofilm formation. Multistrain formulations may by reinforcement of mucus/barrier integrity through microbial–epithelial interactions, and balanced immunomodulation that may reduce excessive Th1/Th17-skewed inflammation while supporting mucosal homeostasis. This was confirmed in our transcriptome data, and their combined effects may enhance the suppression of Th17-driven inflammation and activate the PPAR pathway. We compare these synergistic outcomes to single-strain studies, noting that while individual strains improve antioxidant status and reduce diarrhea [

84,

85], the combination in our study achieved broader benefits, such as more significant reductions in IL-1β, TNF-α, and MDA levels, restoration of SOD/GSH-Px activities and tight junction proteins. Our study demonstrates that mixed probiotic supplementation is a feasible nutritional strategy to mitigate weaning-associated intestinal dysfunction in lambs (

Figure 6). Future work should employ in vitro cell-based models to elucidate the mechanisms by which probiotics regulate host gene expression and immune responses, include protein-level validation to confirm pathway activation and to link transcriptional changes to functional signaling outcomes.