Microbial Metabolism of Levodopa as an Adjunct Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

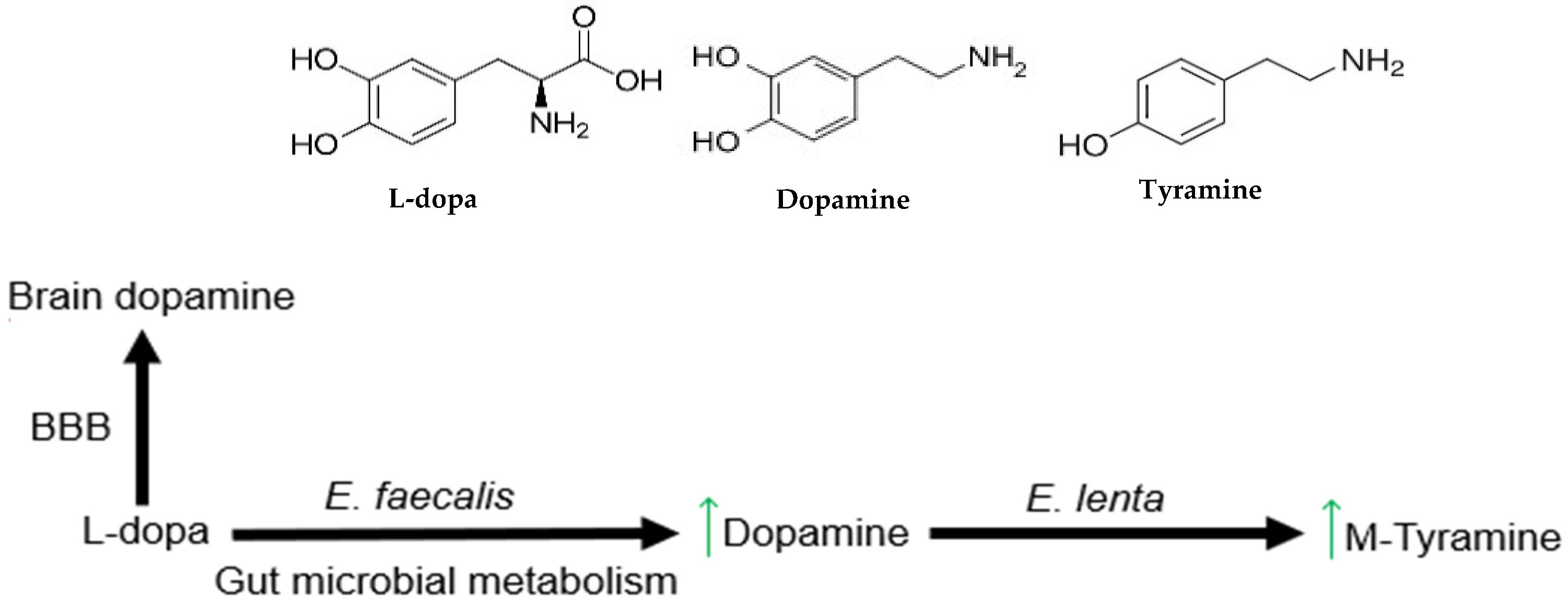

2. Gut Microbial Metabolism of L-Dopa

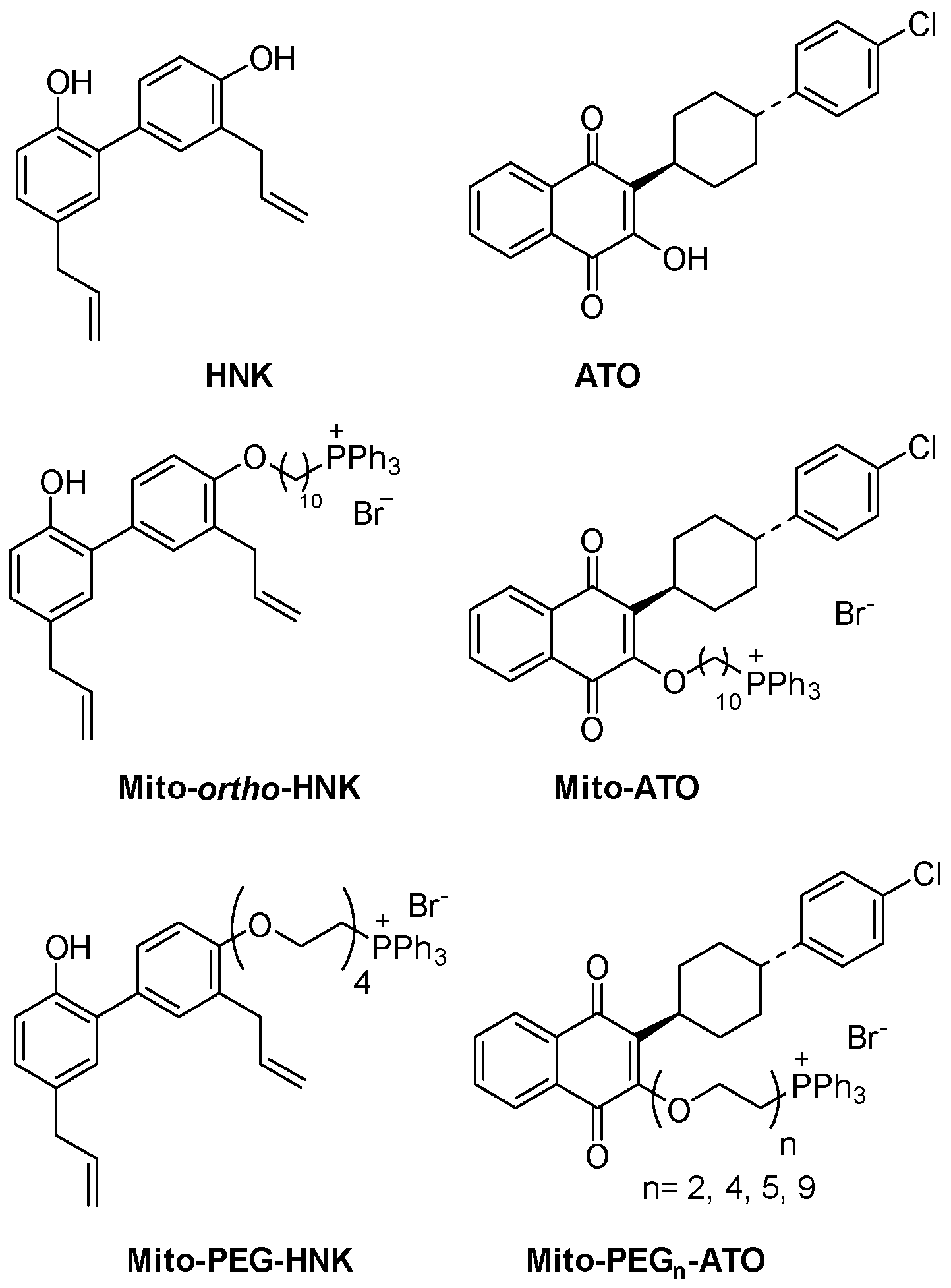

3. MTDs—Antioxidant Effects and Inhibition of Microbial Metabolism

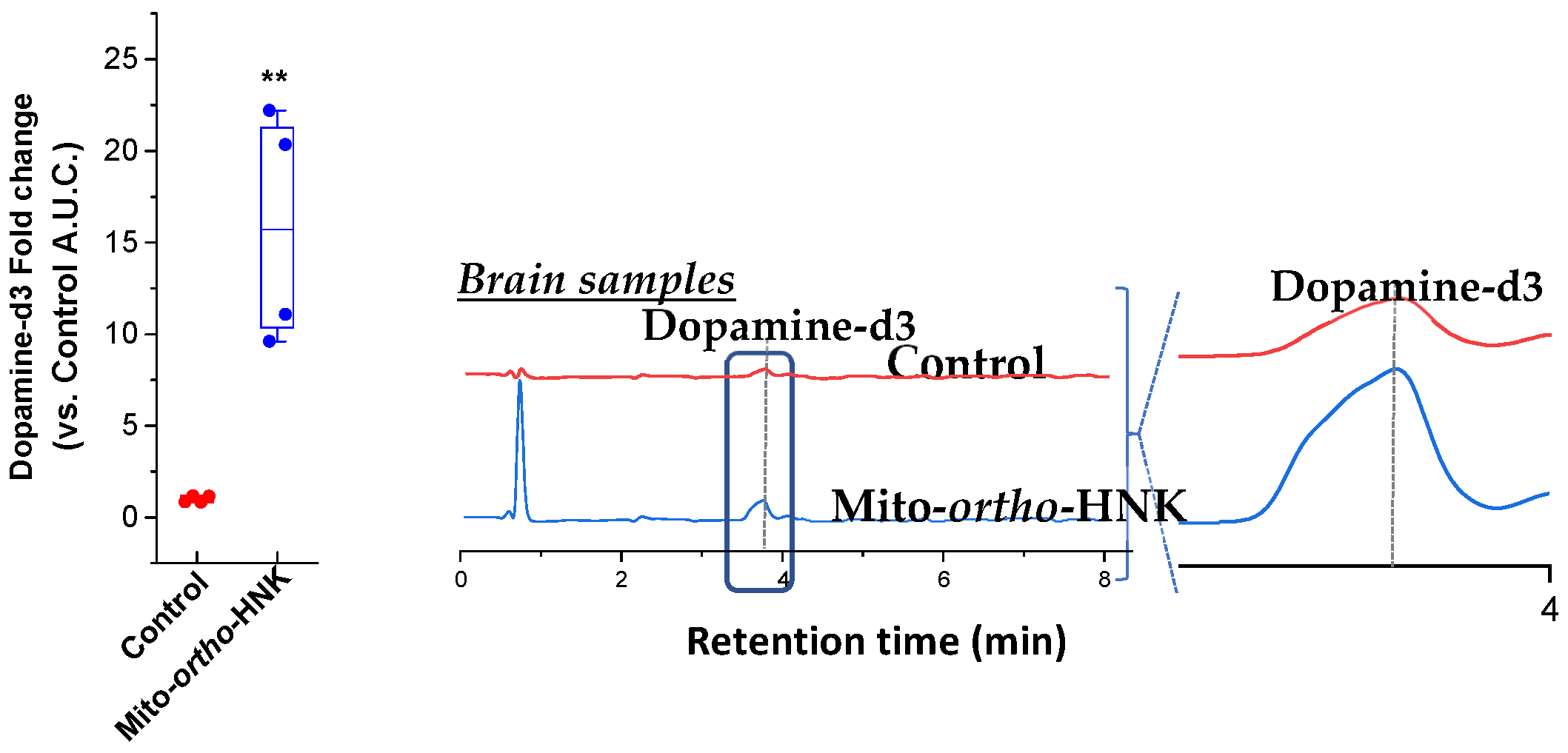

4. In Vivo Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearnley, J.M.; Lees, A.J. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: Substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 1991, 114, 2283–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Hamilton, J.L.; Kopil, C.; Beck, J.C.; Tanner, C.M.; Albin, R.L.; Ray Dorsey, E.; Dahodwala, N.; Cintina, I.; Hogan, P.; et al. Current and projected future economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the U.S. npj Park. Dis. 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Bloem, B.R. The Parkinson Pandemic-A Call to Action. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Evolving Landscape of Parkinson’s Disease Research: Challenges and Perspectives. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 1864–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandemakers, W.; Morais, V.A.; De Strooper, B. A cell biological perspective on mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, W.D., Jr.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesa, J.; Trigo-Damas, I.; Quiroga-Varela, A.; Jackson-Lewis, V.R. Oxidative stress and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neuroanat. 2015, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H.; Chen, C.M. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.M.; De Miranda, B.; Sanders, L.H. Alpha-synuclein: Pathology, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 109, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, M.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Hou, K.; Sun, L.; Wei, J. beta-Synuclein Intermediates alpha-Synuclein Neurotoxicity in Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kanthasamy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Anantharam, V.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Preclinical and clinical outcomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, M.I.; Terzioglu, M.; Galter, D.; Zhu, S.; Hofstetter, C.; Lindqvist, E.; Thams, S.; Bergstrand, A.; Hansson, F.S.; Trifunovic, A.; et al. Progressive parkinsonism in mice with respiratory-chain-deficient dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotzias, G.C.; Van Woert, M.H.; Schiffer, L.M. Aromatic amino acids and modification of parkinsonism. N. Engl. J. Med. 1967, 276, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, S.D.; Iversen, L.L. Dopamine: 50 years in perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S.; Poewe, W. Levodopa: 50 years of a revolutionary drug for Parkinson disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield, A.C.; Moore, B.T.; Daniels, R.N. Classics in chemical neuroscience: Levodopa. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrini, G.; Brotchie, J.M.; Grandas, F.; Nomoto, M.; Goetz, C.G. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Lloret, S.; Negre-Pages, L.; Damier, P.; Delval, A.; Derkinderen, P.; Destee, A.; Meissner, W.G.; Tison, F.; Rascol, O.; On behalf of the COPARK Study Group. L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias, motor fluctuations and health-related quality of life: The COPARK survey. Eur. J. Neurol. 2017, 24, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espay, A.J.; Morgante, F.; Merola, A.; Fasano, A.; Marsili, L.; Fox, S.H.; Bezard, E.; Picconi, B.; Calabresi, P.; Lang, A.E. Levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: Current and evolving concepts. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 84, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, M.; Crescibene, L.; Arabia, G.; Nicoletti, G.; Bagala, A.; Bastone, L.; Caracciolo, M.; Bonavita, S.; Di Costanzo, A.; Scornaienchi, M.; et al. Body weight influences pharmacokinetics of levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2002, 25, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, V.; Izzo, V.; Russillo, M.C.; Picillo, M.; Amboni, M.; Scaglione, C.L.M.; Nicoletti, A.; Cani, I.; Cicero, C.E.; De Bellis, E.; et al. Gender Differences in Levodopa Pharmacokinetics in Levodopa-Naive Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 909936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contin, M.; Lopane, G.; Belotti, L.M.B.; Galletti, M.; Cortelli, P.; Calandra-Buonaura, G. Sex Is the Main Determinant of Levodopa Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Evidence from a Large Series of Levodopa Therapeutic Monitoring. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 2519–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enright, E.F.; Gahan, C.G.; Joyce, S.A.; Griffin, B.T. The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Drug Metabolism and Clinical Outcome. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2016, 89, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Weersma, R.K.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020, 69, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.S.; Mayers, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Bhosle, A.; Glasser, N.R.; Nguyen, L.H.; Ma, W.; Bae, S.; Branck, T.; Song, K.; et al. Gut microbial metabolism of 5-ASA diminishes its clinical efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minato, T.; Maeda, T.; Fujisawa, Y.; Tsuji, H.; Nomoto, K.; Ohno, K.; Hirayama, M. Progression of Parkinson’s disease is associated with gut dysbiosis: Two-year follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.A.; Saltykova, I.V.; Zhukova, I.A.; Alifirova, V.M.; Zhukova, N.G.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.V.; Kovarsky, B.A.; Alekseev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 162, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.A.B.; Aho, V.T.E.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Oral and nasal microbiota in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 38, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003, 2, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.Y.; Park, J.W.; Kim, J.S. The frequency and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. J. Mov. Disord. 2014, 7, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.E. A critical appraisal of the premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Potential usefulness in early diagnosis and design of neuroprotective trials. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundert-Remy, U.; Hildebrandt, R.; Stiehl, A.; Weber, E.; Zurcher, G.; Da Prada, M. Intestinal absorption of levodopa in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1983, 25, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaue, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Liu, S.; Ito, Y.; Yamanishi, Y.; Ando, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Mogi, M.; Nagai, M. Association of Enterococcus faecalis and tyrosine decarboxylase gene levels with levodopa pharmacokinetics in Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielli, M.; Bonazzi, P.; Scarpellini, E.; Bendia, E.; Lauritano, E.C.; Fasano, A.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Capecci, M.; Rita Bentivoglio, A.; Provinciali, L.; et al. Prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Petracca, M.; Zocco, M.A.; Ragazzoni, E.; Barbaro, F.; Piano, C.; Fortuna, S.; Tortora, A.; et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Mahadeva, S.; Thalha, A.M.; Gibson, P.R.; Kiew, C.K.; Yeat, C.M.; Ng, S.W.; Ang, S.P.; Chow, S.K.; Tan, C.T.; et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2014, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Goodwin, B.L.; Ruthven, C.R. Therapeutic implications in Parkinsonism of m-tyramine formation from L-dopa in man. Nature 1971, 229, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldin, B.R.; Peppercorn, M.A.; Goldman, P. Contributions of host and intestinal microflora in the metabolism of L-dopa by the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1973, 186, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kessel, S.P.; Frye, A.K.; El-Gendy, A.O.; Castejon, M.; Keshavarzian, A.; van Dijk, G.; El Aidy, S. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases restrict levels of levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maini Rekdal, V.; Bess, E.N.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Balskus, E.P. Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science 2019, 364, eaau6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M.M. Medical management of Parkinson’s disease. Pharm. Ther. 2008, 33, 590–606. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Hardy, M.; Hillard, C.J.; Feix, J.B.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitigating gut microbial degradation of levodopa and enhancing brain dopamine: Implications in Parkinson’s disease. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Calles-Enriquez, M.; Nes, I.; Martin, M.C.; Fernandez, M.; Ladero, V.; Alvarez, M.A. Tyramine biosynthesis is transcriptionally induced at low pH and improves the fitness of Enterococcus faecalis in acidic environments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3547–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Johnson, R.D.; Ruthven, C.R.; Reid, J.L.; Calne, D.B. Transamination is a major pathway of L-dopa metabolism following peripheral decarboxylase inhibition. Nature 1974, 247, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Lee, Y.; Cheng, G.; Zielonka, J.; Zhang, Q.; Bajzikova, M.; Xiong, D.; Tsaih, S.W.; Hardy, M.; Flister, M.; et al. Mitochondria-Targeted Honokiol Confers a Striking Inhibitory Effect on Lung Cancer via Inhibiting Complex I Activity. iScience 2018, 3, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Hardy, M.; You, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Combining PEGylated mito-atovaquone with MCT and Krebs cycle redox inhibitors as a potential strategy to abrogate tumor cell proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.; Lee, Y.; Ouari, O.; Hardy, M.; Zielonka, M.; Myers, C.R.; Zielonka, J.; Weh, K.; et al. Targeting lonidamine to mitochondria mitigates lung tumorigenesis and brain metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Cheng, G.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitochondria-Targeted Triphenylphosphonium-Based Compounds: Syntheses, Mechanisms of Action, and Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Langley, M.R.; Harischandra, D.S.; Neal, M.L.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; Joseph, J.; Brenza, T.; Narasimhan, B.; Kanthasamy, A.; et al. Mitoapocynin Treatment Protects Against Neuroinflammation and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in a Preclinical Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2016, 11, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, M.; Ghosh, A.; Charli, A.; Sarkar, S.; Ay, M.; Luo, J.; Zielonka, J.; Brenza, T.; Bennett, B.; Jin, H.; et al. Mito-Apocynin Prevents Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Microglial Activation, Oxidative Damage, and Progressive Neurodegeneration in MitoPark Transgenic Mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 1048–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Chandran, K.; Kalivendi, S.V.; Joseph, J.; Antholine, W.E.; Hillard, C.J.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kalyanaraman, B. Neuroprotection by a mitochondria-targeted drug in a Parkinson’s disease model. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, B.J.; Rolfe, F.L.; Lockhart, M.M.; Frampton, C.M.; O’Sullivan, J.D.; Fung, V.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Taylor, K.M.; Protect Study, G. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ as a disease-modifying therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.; Whatley, F.R. Paracoccus denitrificans and the evolutionary origin of the mitochondrion. Nature 1975, 254, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; Smith, R.A. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, P.A.; Osterman, I.A.; Tokarchuk, A.V.; Karakozova, M.V.; Korshunova, G.A.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Skulachev, M.V.; Kotova, E.A.; Skulachev, V.P.; Antonenko, Y.N. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants as highly effective antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Jayakumar, S.; Gupta, G.D.; Bihani, S.C.; Sharma, D.; Kutala, V.K.; Sandur, S.K.; Kumar, V. Antibacterial activity of new structural class of semisynthetic molecule, triphenyl-phosphonium conjugated diarylheptanoid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H.; Chang, P.C.; Wey, S.P.; Chen, P.M.; Chen, C.; Chan, M.H. Therapeutic effects of honokiol on motor impairment in hemiparkinsonian mice are associated with reversing neurodegeneration and targeting PPARgamma regulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.H.; Chang, P.C.; Chen, C.; Chan, M.H. Protective and therapeutic activity of honokiol in reversing motor deficits and neuronal degeneration in the mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 70, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birth, D.; Kao, W.C.; Hunte, C. Structural analysis of atovaquone-inhibited cytochrome bc1 complex reveals the molecular basis of antimalarial drug action. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lin, S.; Dodel, R.C.; Gao, F.; Bales, K.R.; Triarhou, L.C.; Chernet, E.; Perry, K.W.; Nelson, D.L.; et al. Minocycline prevents nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14669–14674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarini, M.; Martin, S.; Mitkovski, M.; Vozari, R.R.; Stuhmer, W.; Bel, E.D. Doxycycline restrains glia and confers neuroprotection in a 6-OHDA Parkinson model. Glia 2013, 61, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, S.R.S.; Mahmud, B.; Dantas, G. Antibiotic perturbations to the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, C.; Taur, Y.; Jenq, R.R.; Equinda, M.J.; Son, T.; Samstein, M.; Viale, A.; Socci, N.D.; van den Brink, M.R.; Kamboj, M.; et al. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus domination of intestinal microbiota is enabled by antibiotic treatment in mice and precedes bloodstream invasion in humans. J. Clin. Invest 2010, 120, 4332–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. faecium | E. faecalis | E. coli BL21 | P. aerug PA01 | |

| HNK | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | NA | NA |

| Mito-ortho-HNK | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | NA | NA |

| Decyl-HNK | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 32 |

| Mito10-ATO | 16 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 64 | 64 |

| Mito-PEG2-ATO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Mito-PEG4-ATO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Mito-PEG5-ATO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 16 |

| Mito-PEG9-ATO | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feix, J.B.; Cheng, G.; Hardy, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Microbial Metabolism of Levodopa as an Adjunct Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010120

Feix JB, Cheng G, Hardy M, Kalyanaraman B. Microbial Metabolism of Levodopa as an Adjunct Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeix, Jimmy B., Gang Cheng, Micael Hardy, and Balaraman Kalyanaraman. 2026. "Microbial Metabolism of Levodopa as an Adjunct Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010120

APA StyleFeix, J. B., Cheng, G., Hardy, M., & Kalyanaraman, B. (2026). Microbial Metabolism of Levodopa as an Adjunct Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants, 15(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010120