Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Reduce Tumor Growth and Promote an Anti-Tumor Immune Response Independent of Cancer KEAP1 Mutational Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Tissue Culture

2.2. Isolation of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages

2.3. Conditioned Media Treatment of Macrophages

2.4. RNA Processing and mRNA Sequencing Analysis

2.5. RT-qPCR

2.6. Mice and Flank Tumor Model

2.7. Immunophenotyping

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. KEAP1 KO Lung Cancer Cells Direct Pro-Tumor Polarization of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages In Vitro

3.2. CDDO-Me Promotes an Anti-Tumor Macrophage Phenotype Regardless of Cancer Cell KEAP1 Status

3.3. CDDO-Me Slows Tumor Growth in Both WT and KEAP1 KO Flank Tumor Models

3.4. The Highly Immunosuppressive KEAP1 KO Microenvironment Reverts with CDDO-Me Treatment

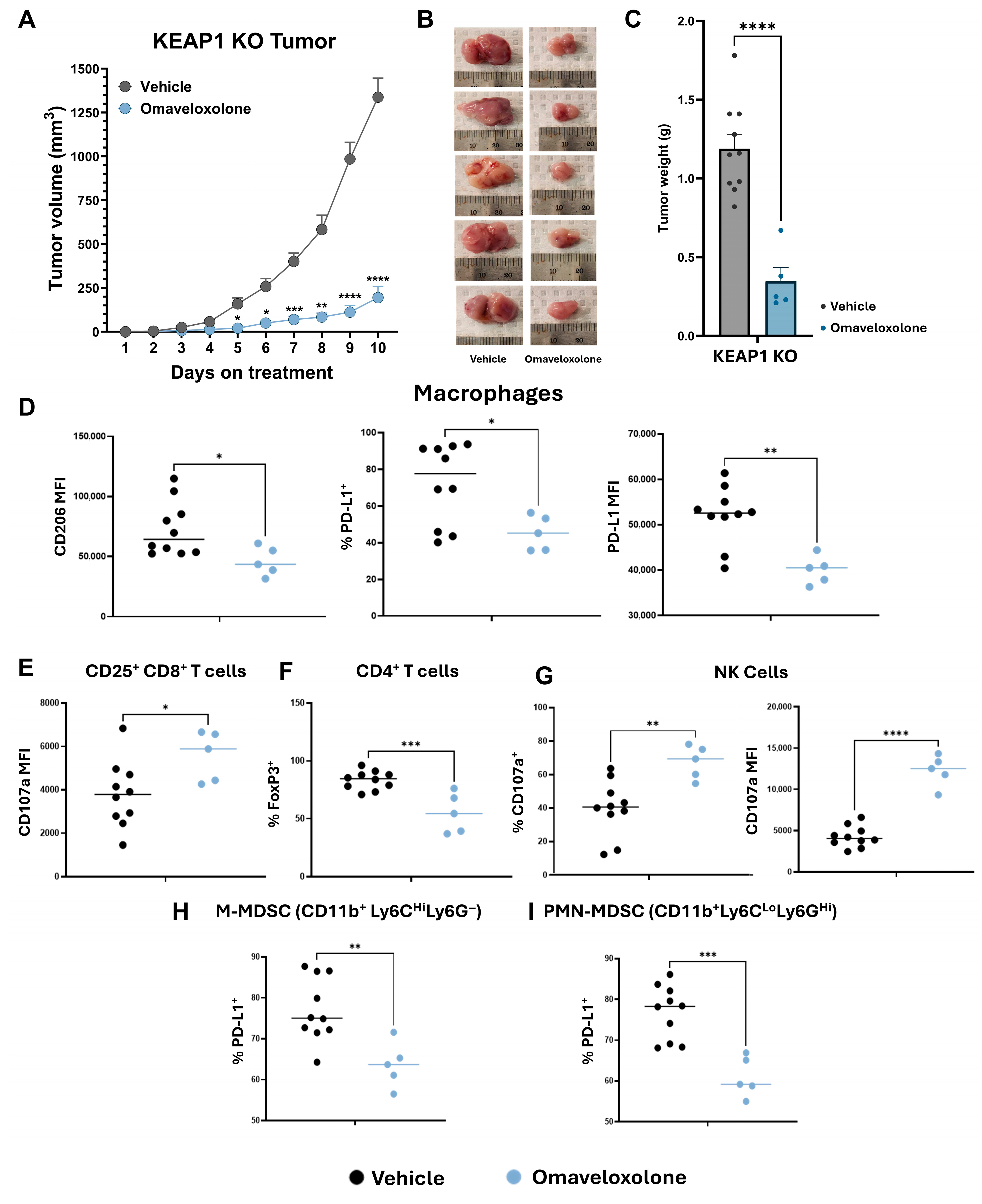

3.5. Omaveloxolone Promotes an Anti-Tumor Microenvironment in KEAP1 KO Flank Tumors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TIME | Tumor immune microenvironment |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| LL2 | Lewis lung carcinoma |

| WT | Wild type |

| KO | Knockout |

| BMDM | Bone marrow-derived macrophage |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| SREBP | Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein |

| CM | Cancer conditioned media |

| PMN-MDSC | Polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| M-MDSC | Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| VEH | Vehicle treatment group |

| ME | CDDO-Me treatment group |

References

- Siegel Mph, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H. and Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jiménez, F.; Muiños, F.; Sentís, I.; Deu-Pons, J.; Reyes-Salazar, I.; Arnedo-Pac, C.; Mularoni, L.; Pich, O.; Bonet, J.; Kranas, H.; et al. A Compendium of Mutational Cancer Driver Genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkala, M. Mutational Landscape of Cancer-Driver Genes across Human Cancers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghban, R.; Roshangar, L.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Ebrahimi-Kalan, A.; Jaymand, M.; Kolahian, S.; Javaheri, T.; Zare, P. Tumor Microenvironment Complexity and Therapeutic Implications at a Glance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Hong, Z.; Bai, X.; Liang, T. Advantages of Targeting the Tumor Immune Microenvironment over Blocking Immune Checkpoint in Cancer Immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta-Pardo, E.; Godzik, A. Mutation Drivers of Immunological Responses to Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Remon, J.; Hellmann, M.D. First-Line Immunotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collisson, E.A.; Campbell, J.D.; Brooks, A.N.; Berger, A.H.; Lee, W.; Chmielecki, J.; Beer, D.G.; Cope, L.; Creighton, C.J.; Danilova, L.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Profiling of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 511, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, C.; Ren, S.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, T. Pan-Cancer Analysis of KEAP1 Mutations as Biomarkers for Immunotherapy Outcomes. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro de Lima, V.C.; Corassa, M.; Saldanha, E.; Freitas, H.; Arrieta, O.; Raez, L.; Samtani, S.; Ramos, M.; Rojas, C.; Burotto, M.; et al. STK11 and KEAP1 Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Descriptive Analysis and Prognostic Value among Hispanics (STRIKE Registry-CLICaP). Lung Cancer 2022, 170, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Hellyer, J.A.; Stehr, H.; Hoang, N.T.; Niu, X.; Das, M.; Padda, S.K.; Ramchandran, K.; Neal, J.W.; Wakelee, H.; et al. Role of KEAP1/NFE2L2 Mutations in the Chemotherapeutic Response of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 26, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanen, E.; Kuosmanen, S.M.; Leinonen, H.; Levonenn, A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway: Mechanisms of Activation and Dysregulation in Cancer. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalera, S.; Mazzotta, M.; Cortile, C.; Krasniqi, E.; De Maria, R.; Cappuzzo, F.; Ciliberto, G.; Maugeri-Saccà, M. KEAP1-Mutant NSCLC: The Catastrophic Failure of a Cell-Protecting Hub. J. Thoracic Oncol. 2022, 17, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, D.; Mazzotta, M.; Scalera, S.; Terrenato, I.; Sperati, F.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Pallocca, M.; Corleone, G.; Krasniqi, E.; Pizzuti, L.; et al. KEAP1-Driven Co-Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma Unresponsive to Immunotherapy despite High Tumor Mutational Burden. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H.; Fang, S. Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients with KEAP1 Mutation Harboring Low Immune Cell Infiltration and Low Activity of Immune Environment. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, V.; Cordani, N.; Villa, A.M.; Malighetti, F.; Villa, M.; Sala, L.; Aroldi, A.; Piazza, R.; Cortinovis, D.; Mologni, L.; et al. Integrative Analysis of KEAP1/NFE2L2 Alterations across 3600+ Tumors Reveals an NRF2 Expression Signature as a Prognostic Biomarker in Cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.S.; Qassem, K.; Islam, S.; Parag, R.R.; Rahman, M.Z.; Farhat, W.A.; Yeger, H.; Aboussekhra, A.; Karakas, B.; Noman, A.S.M. Genetic Alterations of Keap1 Confers Chemotherapeutic Resistance through Functional Activation of Nrf2 and Notch Pathway in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1–NRF2 System as a Molecular Target of Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2020, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Daemen, A.; Nickles, D.; Jeon, S.M.; Foreman, O.; Sudini, K.; Gnad, F.; Lajoie, S.; Gour, N.; Mitzner, W.; et al. NRF2 Activation Promotes Aggressive Lung Cancer and Associates with Poor Clinical Outcomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi, S.; Patinen, T.; Jawahar Deen, A.; Pitkänen, S.; Härkönen, J.; Kansanen, E.; Küblbeck, J.; Levonen, A.L. The KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway: Targets for Therapy and Role in Cancer. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouremamali, F.; Pouremamali, A.; Dadashpour, M.; Soozangar, N.; Jeddi, F. An Update of Nrf2 Activators and Inhibitors in Cancer Prevention/Promotion. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borella, R.; Forti, L.; Gibellini, L.; De Gaetano, A.; De Biasi, S.; Nasi, M.; Cossarizza, A.; Pinti, M. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of CDDO and CDDO-Me, Two Derivatives of Natural Triterpenoids. Molecules 2019, 24, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Sarwar, M.S.; Chou, P.; Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Kong, A.N.T. PTEN-Knockout Regulates Metabolic Rewiring and Epigenetic Reprogramming in Prostate Cancer and Chemoprevention by Triterpenoid Ursolic Acid. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, D.; Gao, X.; Jiang, H.; Dulchavsky, S.A.; Gautam, S.C. Oleanane Triterpenoid CDDO-Me Inhibits Growth and Induces Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer Cells by Independently Targeting pro-Survival Akt and MTOR. Prostate 2009, 69, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashmawy, M.; Delgado, O.; Cardentey, A.; Wright, W.E.; Shay, J.W. CDDO-Me Protects Normal Lung and Breast Epithelial Cells but Not Cancer Cells from Radiation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e0115600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeb, D.; Gao, X.; Jiang, H.; Janic, B.; Arbab, A.S.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Dulchavsky, S.A.; Gautam, S.C. Oleanane Triterpenoid CDDO-Me Inhibits Growth and Induces Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer Cells through a ROS-Dependent Mechanism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerland, J.A.; Leal, A.S.; Lockwood, B.; Demireva, E.Y.; Xie, H.; Krieger-Burke, T.; Liby, K.T. The Triterpenoid CDDO-Methyl Ester Redirects Macrophage Polarization and Reduces Lung Tumor Burden in a Nrf2-Dependent Manner. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavoni, V.; Di Crescenzo, T.; Membrino, V.; Alia, S.; Fantone, S.; Salvolini, E.; Vignini, A. Bardoxolone Methyl: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role as a Nrf2 Activator in Anticancer Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Zhe, H.; He, Z.X.; Zhou, S.F. Bardoxolone Methyl (CDDO-Me) as a Therapeutic Agent: An Update on Its Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Omaveloxolone: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.S.; Bhandari, R.; Torres, G.M.; Martyanov, V.; ElTanbouly, M.A.; Archambault, K.; Whitfield, M.L.; Liby, K.T.; Pioli, P.A. CDDO-Me Alters the Tumor Microenvironment in Estrogen Receptor Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huo, M.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L. Nanoparticle Delivery of CDDO-Me Remodels the Tumor Microenvironment and Enhances Vaccine Therapy for Melanoma. Biomaterials 2015, 68, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerland, J.A.; Liby, K.T. The Triterpenoid CDDO-Methyl Ester Reduces Tumor Burden, Reprograms the Immune Microenvironment, and Protects from Chemotherapy-Induced Toxicity in a Preclinical Mouse Model of Established Lung Cancer. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C.; Enríquez, C.; González, C.; Aguirre-Martínez, G.; Buc Calderon, P. The Multifaceted Roles of NRF2 in Cancer: Friend or Foe? Antioxidants 2024, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.; Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, C. Loss-of-Function Mutations in KEAP1 Drive Lung Cancer Progression via KEAP1/NRF2 Pathway Activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavitsanou, A.-M.; Pillai, R.; Hao, Y.; Wu, W.L.; Bartnicki, E.; Karakousi, T.; Rajalingam, S.; Herrera, A.; Karatza, A.; Rashidfarrokhi, A.; et al. KEAP1 Mutation in Lung Adenocarcinoma Promotes Immune Evasion and Immunotherapy Resistance. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.D. Thirty Years of NRF2: Advances and Therapeutic Challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Kuga, A.; Suzuki, M.; Panda, H.; Kitamura, H.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Microenvironmental Activation of Nrf2 Restricts the Progression of Nrf2-Activated Malignant Tumors. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 3331–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhiuto, C.J.; Liby, K.T. KEAP1-Mutant Lung Cancers Weaken Anti-Tumor Immunity and Promote an M2-like Macrophage Phenotype. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-Optimal Probabilistic RNA-Seq Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melsted, P.; Booeshaghi, A.S.; Liu, L.; Gao, F.; Lu, L.; Min, K.H.; da Veiga Beltrame, E.; Hjörleifsson, K.E.; Gehring, J.; Pachter, L. Modular, Efficient and Constant-Memory Single-Cell RNA-Seq Preprocessing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Voom: Precision Weights Unlock Linear Model Analysis Tools for RNA-Seq Read Counts. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. Thirteen Years of ClusterProfiler. Innovation 2024, 5, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. ClusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.R.A.; O’Koren, E.G.; Hotten, D.F.; Kan, M.J.; Kopin, D.; Nelson, E.R.; Que, L.; Gunn, M.D. A Protocol for the Comprehensive Flow Cytometric Analysis of Immune Cells in Normal and Inflamed Murine Non-Lymphoid Tissues. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.posit.co/.

- He, Q.; Sun, C.; Pan, Y. Whole-exome Sequencing Reveals Lewis Lung Carcinoma Is a Hypermutated Kras/Nras–Mutant Cancer with Extensive Regional Mutation Clusters in Its Genome. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marelli, G.; Morina, N.; Portale, F.; Pandini, M.; Iovino, M.; Di Conza, G.; Ho, P.C.; Di Mitri, D. Lipid-Loaded Macrophages as New Therapeutic Target in Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlauckas, S.P.; Garren, S.B.; Garris, C.S.; Kohler, R.H.; Oh, J.; Pittet, M.J.; Weissleder, R. Arg1 Expression Defines Immunosuppressive Subsets of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Theranostics 2018, 8, 5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menjivar, R.E.; Nwosu, Z.C.; Du, W.; Donahue, K.L.; Hong, H.S.; Espinoza, C.; Brown, K.; Velez-Delgado, A.; Yan, W.; Lima, F.; et al. Arginase 1 Is a Key Driver of Immune Suppression in Pancreatic Cancer. eLife 2023, 12, e80721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, T.; Kang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J. Crosstalk between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Tumor Cells Promotes Chemoresistance via CXCL5/PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radharani, N.N.V.; Yadav, A.S.; Nimma, R.; Kumar, T.V.S.; Bulbule, A.; Chanukuppa, V.; Kumar, D.; Patnaik, S.; Rapole, S.; Kundu, G.C. Tumor-Associated Macrophage Derived IL-6 Enriches Cancer Stem Cell Population and Promotes Breast Tumor Progression via Stat-3 Pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Dang, P.; Hu, S.; Yuan, W.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. Roles of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Immunotherapy for Solid Cancers. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasser, S.A.; Ozbay Kurt, F.G.; Arkhypov, I.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer and Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy, R.; Pollard, J.W. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Immunity 2014, 41, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Chikina, M.; Deshpande, R.; Menk, A.V.; Wang, T.; Tabib, T.; Brunazzi, E.A.; Vignali, K.M.; Sun, M.; Stolz, D.B.; et al. Treg Cells Promote the SREBP1-Dependent Metabolic Fitness of Tumor-Promoting Macrophages via Repression of CD8+ T Cell-Derived Interferon-γ. Immunity 2019, 51, 381–397.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidault, G.; Virtue, S.; Petkevicius, K.; Jolin, H.E.; Dugourd, A.; Guénantin, A.C.; Leggat, J.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; Lam, B.Y.H.; Ma, M.K.; et al. SREBP1-Induced Fatty Acid Synthesis Depletes Macrophages Antioxidant Defences to Promote Their Alternative Activation. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; He, H.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; et al. Tumour-Associated Macrophages-Derived CXCL8 Determines Immune Evasion through Autonomous PD-L1 Expression in Gastric Cancer. Gut 2019, 68, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinchi, Y.; Ishizuka, S.; Komohara, Y.; Matsubara, E.; Mito, R.; Pan, C.; Yoshii, D.; Yonemitsu, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; Ikeda, K.; et al. The Expression of PD-1 Ligand 1 on Macrophages and Its Clinical Impacts and Mechanisms in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebeler, R.; de Winther, M.P.J.; Hoeksema, M.A. The Regulatory Landscape of Macrophage Interferon Signaling in Inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in Tumor Progression and Regression: A Review. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, L.; Che, G.; Yu, N.; Dai, F.; You, Z. The M1 Form of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Is Positively Associated with Survival Time. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafrilla, P.; Marhuenda, J.; Cerdá, B.; Pérez, S.; Rius-Pérez, S. Macrophage Polarization and Reprogramming in Acute Inflammation: A Redox Perspective. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.P.; Bauer, R.; Brüne, B.; Schmid, T. The Role of Type I Interferon Signaling in Myeloid Anti-Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1547466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.M.; Yang, H.; Park, C.; Spezza, P.A.; Khatwani, N.; Bhandari, R.; Liby, K.T.; Pioli, P.A. T Cells and CDDO-Me Attenuate Immunosuppressive Activation of Human Melanoma-Conditioned Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares, L.; Moreno, R.; Ali, K.X.; Higgins, M.; Dayalan Naidu, S.; Neill, G.; Cassin, L.; Kiib, A.E.; Svenningsen, E.B.; Minassi, A.; et al. The Synthetic Triterpenoids CDDO-TFEA and CDDO-Me, but Not CDDO, Promote Nuclear Exclusion of BACH1 Impairing Its Activity: CDDO-Derivatives Inhibit BACH1. Redox Biol. 2022, 51, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.S.; Kurzrock, R.; Supko, J.G.; He, X.; Naing, A.; Wheler, J.; Lawrence, D.; Eder, J.P.; Meyer, C.J.; Ferguson, D.A.; et al. A Phase I First-in-Human Trial of Bardoxolone Methyl in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors and Lymphomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3396–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj, S.; Youn, J.I.; Weber, H.; Iclozan, C.; Lu, L.; Cotter, M.J.; Meyer, C.; Becerra, C.R.; Fishman, M.; Antonia, S.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Triterpenoid Blocks Immune Suppressive Function of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Improves Immune Response in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.R.; Chin, M.P.; Delatycki, M.B.; Subramony, S.H.; Corti, M.; Hoyle, J.C.; Boesch, S.; Nachbauer, W.; Mariotti, C.; Mathews, K.D.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Omaveloxolone in Friedreich Ataxia (MOXIe Study). Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Occhiuto, C.J.; Moerland, J.A.; Liby, K.T.; Leal, A.S. Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Reduce Tumor Growth and Promote an Anti-Tumor Immune Response Independent of Cancer KEAP1 Mutational Status. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121406

Occhiuto CJ, Moerland JA, Liby KT, Leal AS. Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Reduce Tumor Growth and Promote an Anti-Tumor Immune Response Independent of Cancer KEAP1 Mutational Status. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(12):1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121406

Chicago/Turabian StyleOcchiuto, Christopher J., Jessica A. Moerland, Karen T. Liby, and Ana S. Leal. 2025. "Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Reduce Tumor Growth and Promote an Anti-Tumor Immune Response Independent of Cancer KEAP1 Mutational Status" Antioxidants 14, no. 12: 1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121406

APA StyleOcchiuto, C. J., Moerland, J. A., Liby, K. T., & Leal, A. S. (2025). Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Reduce Tumor Growth and Promote an Anti-Tumor Immune Response Independent of Cancer KEAP1 Mutational Status. Antioxidants, 14(12), 1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14121406