Microbial Biotransformation of Agro-Industrial Fibre-Rich By-Products into Functional Beverages

Abstract

1. Introduction

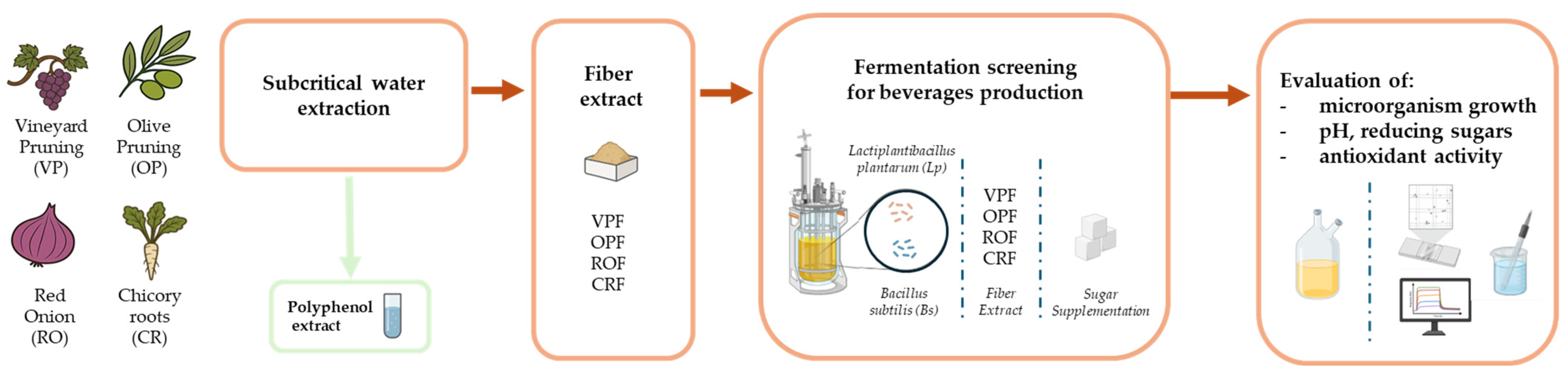

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Recovery of the Remaining Fibre Fraction After Extraction of Polyphenols by Subcritical Water Extraction

2.3. Material Characterisation

2.3.1. Moisture Content

2.3.2. Water-Holding Capacity (WHC)

2.4. Production of Fermented Beverages

2.4.1. Propagation of the Inoculum

2.4.2. Procedure of Screening Experiments

2.4.3. Procedure of Scaled Experiments

2.5. Fermented Beverage Monitoring

2.5.1. pH

2.5.2. Count of Viable Microorganisms

2.5.3. Reducing Sugar Content

2.5.4. Total Polyphenol Content

2.5.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.5.6. Sensory Evaluation—Preliminary Screening

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterisation of Fibre Extract By-Products

3.1.1. Production of Fermented Beverages

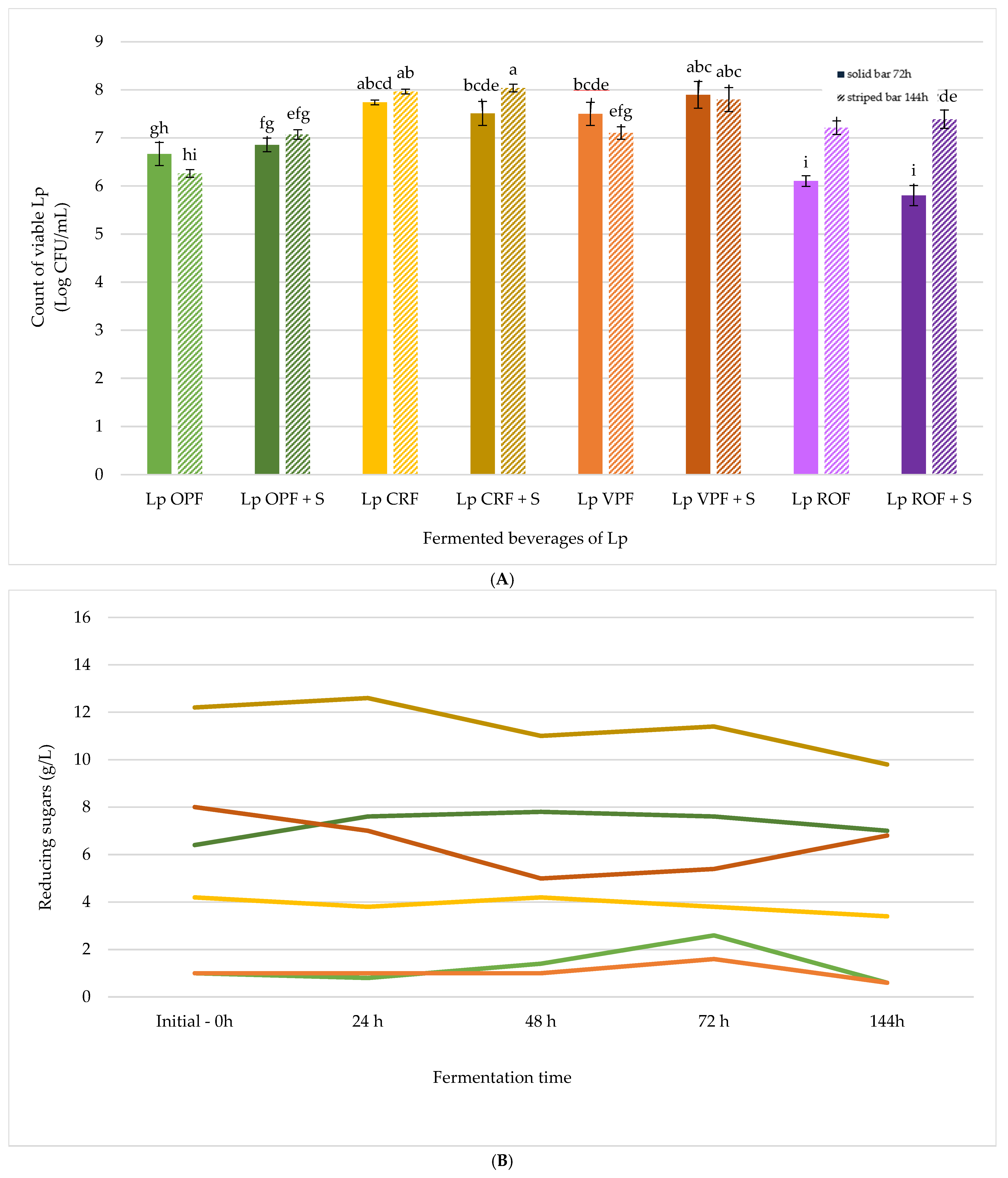

3.1.2. Screening of Fermented Beverages with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Bacillus subtilis of Vegetable By-Products

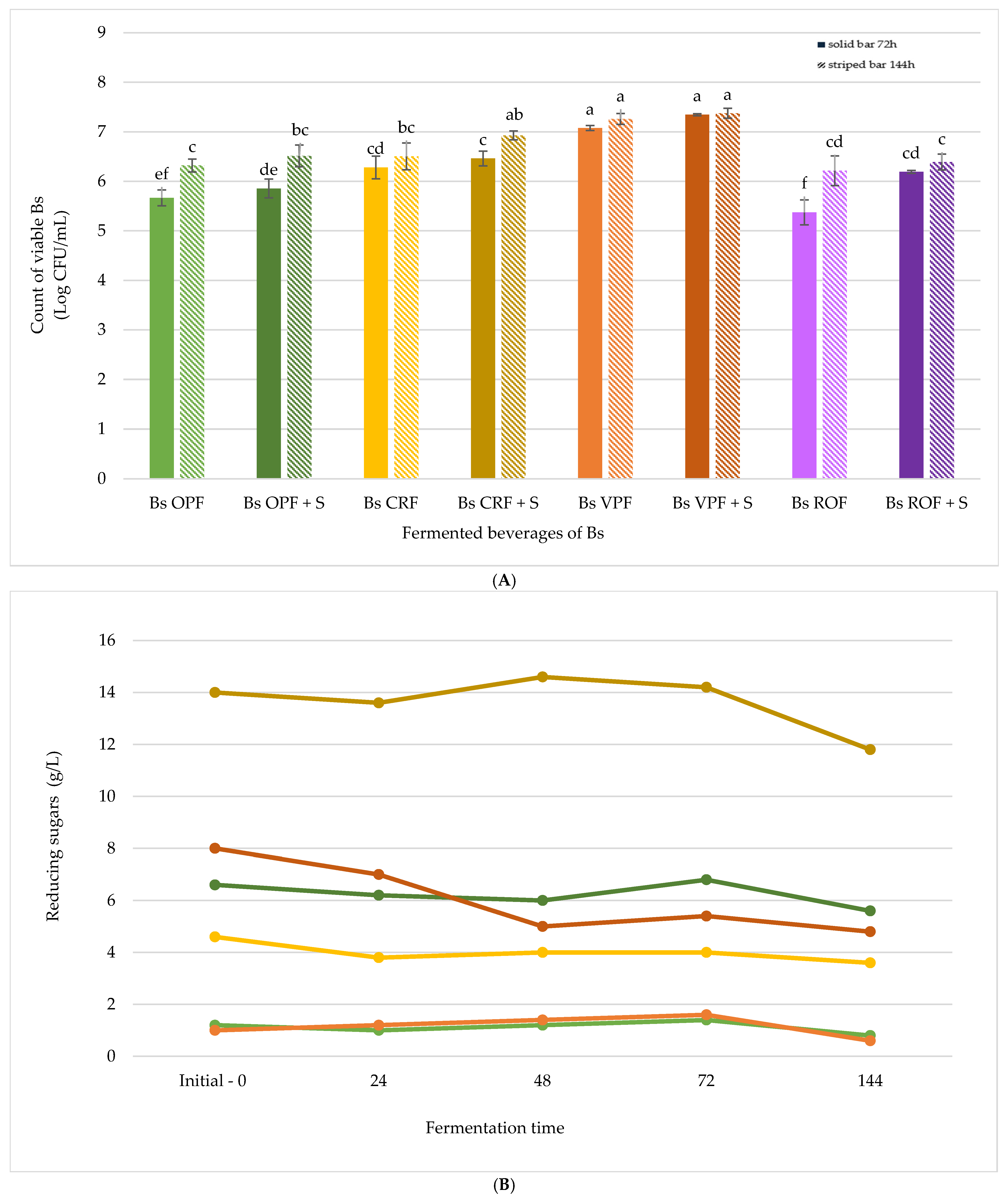

3.1.3. Screening of Fermented Beverages with Bacillus subtilis

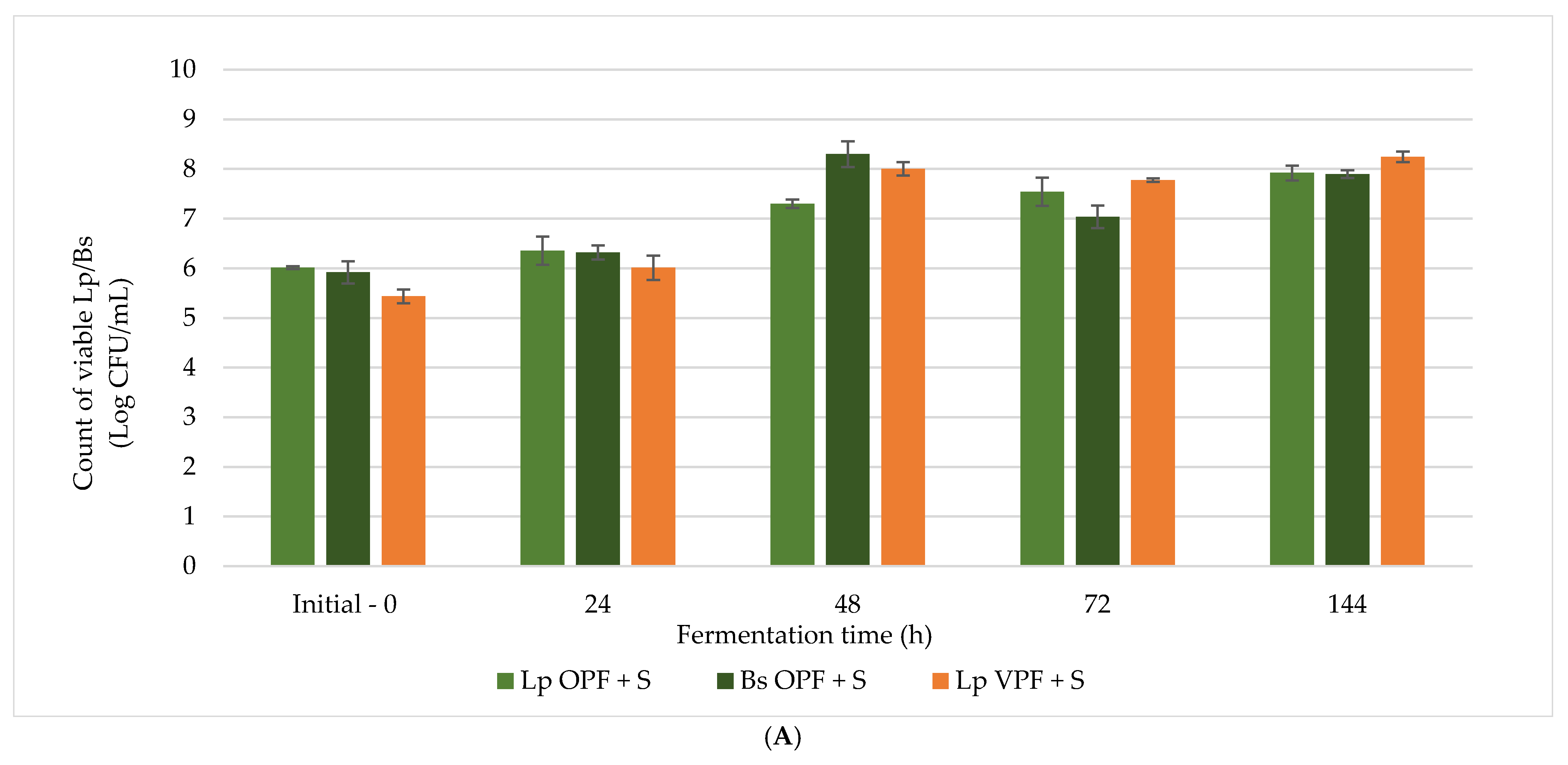

3.1.4. Comparative Evaluation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Bacillus subtilis

3.2. Scale-Up of Fermented Beverages

3.3. Antioxidant Potential of Scale-Up Fermented Beverages

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laaninen, T.; Calasso, M.P. Reducing Food Waste in the European Union. December 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/659376/EPRS_BRI(2020)659376_EN.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Maqsood, S.; Khalid, W.; Kumar, P.; Benmebarek, I.E.; Rasool, I.F.U.; Trif, M.; Moreno, A.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Valorization of plant-based agro-industrial waste and by-products for the production of polysaccharides: Towards a more circular economy. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, A. Bioconversion of food industry waste to value added products: Current technological trends and prospects. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, W.J.; Agro, N.C.; Eliasson, Å.M.; Mialki, K.L.; Olivera, J.D.; Rusch, C.T.; Young, C.N. Health Benefits of Fiber Fermentation. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, M.; Hati, S. Fermented beverages and their health benefits. In Fermented Beverages: Volume 5. The Science of Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, H.; Li, H.; Xie, Y.; Ding, K.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Yi, C.; Ding, S. Co-fermentation of Lactiplantibacillus and Streptococcusccus enriches the key-contribution volatile and non-volatile components of jujube juice. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Hu, M.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, S. Efficient conversion of insoluble dietary fiber to soluble dietary fiber by Bacillus subtilis BSNK-5 fermentation of okara and improvement of their structural and functional properties. Food Chem. 2025, 474, 143188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Guo, Q.; Shi, L.; Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Xiao, C. Effects of fermentation with lactic bacteria on the structural characteristics and physicochemical and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber from prosomillet bran. LWT 2022, 154, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ni, Y.; Yu, Q.; Fan, L. Evaluation of co-fermentation of L. plantarum and P. kluyveri of a plant-based fermented beverage: Physicochemical, functional, and sensory properties. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buatong, A.; Meidong, R.; Trongpanich, Y.; Tongpim, S. Production of plant-based fermented beverages possessing functional ingredients antioxidant, γ-aminobutyric acid and antimicrobials using a probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain L42g as an efficient starter culture. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022, 134, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zokaityte, E.; Lele, V.; Starkute, V.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Cernauskas, D.; Klupsaite, D.; Ruzauskas, M.; Alisauskaite, J.; Baltrusaitytė, A.; Dapsas, M.; et al. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Sensory Properties, and Emotions Induced for the Consumers of Nutraceutical Beverages Developed from Technological Functionalised Food Industry By-Products. Foods 2020, 9, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.; Akbar, A.; Gul, Z.; Sadiq, M.B.; Achakzai, J.K.; Khan, N.A. Fermentation impact: A comparative study on the functional and biological properties of Banana peel waste. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Bansal, S.; Mangal, M.; Dixit, A.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Mangal, A.K. Utilization of food processing by-products as dietary, functional, and novel fiber: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filannino, P.; Bai, Y.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Gänzle, M.G. Metabolism of phenolic compounds by Lactobacillus spp. during fermentation of cherry juice and broccoli puree. Food Microbiol. 2015, 46, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, T.; Mao, J.; Sha, R. Effects of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Physicochemical Properties, Functional Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Edible Grass. Fermentation 2022, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Hu, X. Solvent retention capacity of oat flour: Relationship with oat β-glucan content and molecular weight. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, L.C.; Bettge, A.D.; Slade, L. Soft wheat and flour products methods review: Solvent retention capacity equation correction. Cereal Foods World 2009, 54, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Aguiar, N.F.B.; Voss, G.B.; Pintado, M.E. Properties of Fermented Beverages from Food Wastes/By-Products. Beverages 2023, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Prior, R.L. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4619–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Cecchi, T.; Lombardelli, C.; Maresca, D.; Mauriello, G.; Esti, M. Novel microencapsulated yeast for the primary fermentation of green beer: Kinetic behavior, volatiles and sensory profile. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Tindjau, R.; Liu, S.Q. Enzymatic hydrolysis and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v fermentation enabled bioconversion of leftover rice into a potential plant-based probiotic beverage. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, P.; Song, K.P.; Choo, W.S. Viability, storage stabilityand in vitro gastrointestinal tolerance of lactiplantibacillus plantarum grown in model sugar systems with inulin and fructooligosaccharide supplementation. Fermentation 2021, 7, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Gao, Y.; Meng, W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.; Li, S. Controlled release mechanism of off-flavor compounds in Bacillus subtilis BSNK-5 fermented soymilk and flavor improvement by phenolic compounds. Food Res. Int. 2025, 207, 116028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Bi, X.; Liu, X. Characteristics of microbial communities in fermentation of pickled ginger and their correlation with its volatile flavors. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, W.; Ma, W.; Qian, J.Y.; et al. Antioxidant capacity, flavor and physicochemical properties of FH06 functional beverage fermented by lactic acid bacteria: A promising method to improve antioxidant activity and flavor of plant functional beverage. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Ni, D.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Wang, L. Effects of Fermentation on Bioactivity and the Composition of Polyphenols Contained in Polyphenol-Rich Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, L. Fermentation of Lactobacillus fermentum NB02 with feruloyl esterase production increases the phenolic compounds content and antioxidant properties of oat bran. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C.; Coppola, F.; Iorizzo, M. β-Glucosidase Activity of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: A Key Player in Food Fermentation and Human Health. Foods 2025, 14, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Dey, P. Bacterial exopolysaccharides as emerging bioactive macromolecules: From fundamentals to applications. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IDissanayake, H.; Tabassum, W.; Alsherbiny, M.; Chang, D.; Li, C.G.; Bhuyan, D.J. Lactic acid bacterial fermentation as a biotransformation strategy to enhance the bioavailability of phenolic antioxidants in fruits and vegetables: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waszkowiak, K.; Makowska, A.; Mikołajczak, B.; Myszka, K.; Barthet, V.J.; Zielińska-Dawidziak, M.; Kmiecik, D.; Truszkowska, M. Fermenting of flaxseed cake with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K06 to increase its application as food ingredient—The effect on changes in protein and phenolic profiles, cyanogenic glycoside degradation, and functional properties. LWT 2025, 217, 117419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lp OPF,

Lp OPF,  Lp OPF + S,

Lp OPF + S,  Lp CRF,

Lp CRF,  Lp CRF + S,

Lp CRF + S,  Lp VPF,

Lp VPF,  Lp VPF + S,

Lp VPF + S,  Lp ROF, and

Lp ROF, and  Lp ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Lp ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Lp OPF,

Lp OPF,  Lp OPF + S,

Lp OPF + S,  Lp CRF,

Lp CRF,  Lp CRF + S,

Lp CRF + S,  Lp VPF,

Lp VPF,  Lp VPF + S,

Lp VPF + S,  Lp ROF, and

Lp ROF, and  Lp ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Lp ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Bs OPF,

Bs OPF,  Bs OPF + S,

Bs OPF + S,  Bs CRF,

Bs CRF,  Bs CRF + S,

Bs CRF + S,  Bs VPF,

Bs VPF,  Bs VPF + S,

Bs VPF + S,  Bs ROF, and

Bs ROF, and  Bs ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Bs ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Bs OPF,

Bs OPF,  Bs OPF + S,

Bs OPF + S,  Bs CRF,

Bs CRF,  Bs CRF + S,

Bs CRF + S,  Bs VPF,

Bs VPF,  Bs VPF + S,

Bs VPF + S,  Bs ROF, and

Bs ROF, and  Bs ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

Bs ROF + S. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between fermented beverages at p < 0.05.

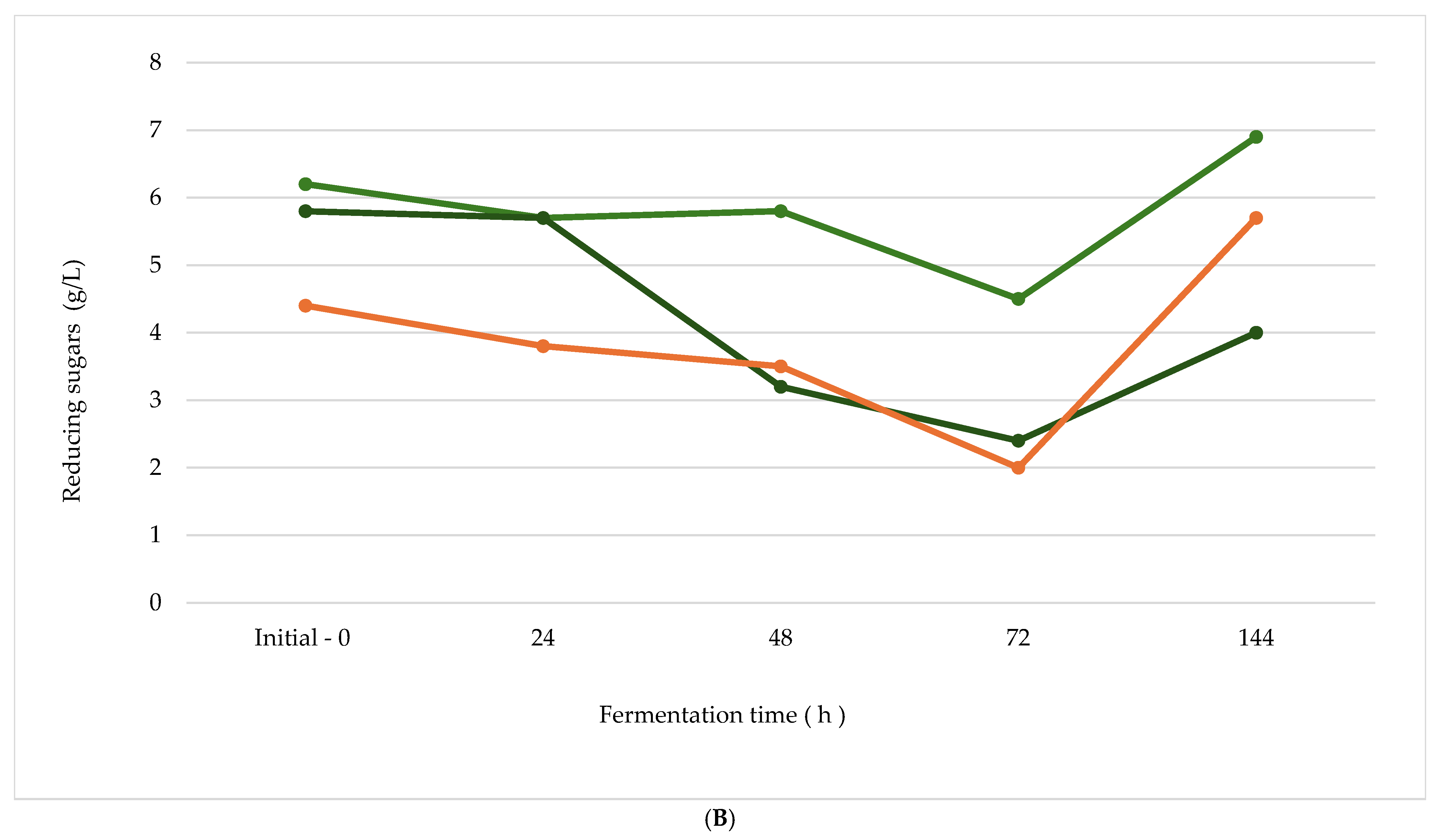

Lp OPF + S,

Lp OPF + S,  Bs OPF + S, and

Bs OPF + S, and  Lp VPF + S.

Lp VPF + S.

Lp OPF + S,

Lp OPF + S,  Bs OPF + S, and

Bs OPF + S, and  Lp VPF + S.

Lp VPF + S.

| Microorganism Inoculated | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (Lp) | Bacillus subtilis (Bs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Addition | Sugar (S): 10 g/L | No Addition | Sugar (S): 10 g/L | |

| OPF | Lp OPF | Lp OPF + S | Bs OPF | Bs OPF + S |

| VPF | Lp VPF | Lp VPF + S | Bs VPF | Bs VPF + S |

| CRF | Lp CRF | Lp CRF + S | Bs CRF | Bs CRF + S |

| ROF | Lp ROF | Lp ROF + S | Bs ROF | Bs ROF + S |

| Source | Moisture (g/100 g) | Water-Holding Capacity (%) | Soluble Fibre (%) | Insoluble Fibre (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPF | 7.75 ± 0.23 a | 285.43 ± 2.38 d | 2.70 ± 0.50 a | 83.20 ± 1.70 a |

| VPF | 5.19 ± 0.16 b | 388.06 ± 8.11 b | 0.50 ± 0.10 b | 90.50 ± 0.90 b |

| CRF | 4.35 ± 0.20 b | 357.37 ± 3.09 c | 0.50 ± 0.10 b | 55.90 ± 0.50 c |

| ROF | 8.06 ± 0.22 a | 456.65 ± 2.52 a | 1.50 ± 0.30 c | 73.30 ± 0.90 d |

| pH | Initial (0 h) | Fermentation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 144 h | ||

| Lp OPF | 4.96 | 4.85 | 4.77 | 4.60 | 4.43 |

| Lp OPF + S | 4.95 | 4.83 | 4.72 | 4.55 | 4.27 |

| Lp VPF | 4.72 | 4.71 | 4.64 | 4.42 | 4.37 |

| Lp VPF + S | 4.71 | 4.66 | 4.52 | 4.34 | 4.22 |

| Lp CRF | 5.54 | 5.43 | 5.35 | 5.27 | 5.01 |

| Lp CRF + S | 5.55 | 5.33 | 5.05 | 5.03 | 4.90 |

| Lp ROF | 4.49 | 4.50 | 4.43 | 4.46 | 4.14 |

| Lp ROF + S | 4.50 | 4.35 | 4.33 | 4.33 | 4.07 |

| pH | Initial (0 h) | Fermentation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 144 h | ||

| Bs OPF | 4.98 | 5.02 | 4.96 | 5.05 | 4.99 |

| Bs OPF + S | 4.97 | 5.01 | 4.93 | 5.04 | 4.91 |

| Bs VPF | 4.70 | 4.70 | 4.70 | 4.72 | 4.62 |

| Bs VPF + S | 4.68 | 4.66 | 4.65 | 4.60 | 4.51 |

| Bs CRF | 5.51 | 5.66 | 5.69 | 5.45 | 5.32 |

| Bs CRF + S | 5.48 | 5.65 | 5.65 | 5.46 | 5.29 |

| Bs ROF | 4.50 | 4.51 | 4.54 | 4.50 | 4.35 |

| Bs ROF + S | 4.52 | 4.48 | 4.46 | 4.46 | 4.31 |

| pH | Initial (0 h) | Fermentation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 144 h | ||

| Lp OPF + S | 5.05 | 4.97 | 4.91 | 4.87 | 4.23 |

| Bs OPF + S | 5.04 | 4.98 | 4.89 | 4.76 | 4.35 |

| Lp VPF + S | 4.77 | 4.68 | 4.32 | 3.98 | 3.91 |

| Scale-Up Fermented Beverage | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/L) | ORAC (µmol Trolox/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 72 h | 144 h | Control | 72 h | 144 h | |

| Bs OPF + S | 169.80 ± 1.98 b | 201.98 ± 3.42 a | 139.68 ± 3.85 c | 607.54 ± 7.07 a | 268.05 ± 4.91 c | 309.45 ± 6.79 b |

| Lp OPF + S | 169.80 ± 1.98 a | 5.70 ± 0.99 c | 17.88 ± 0.74 b | 607.54 ± 7.07 b | 709.25 ± 5.08 a | 750.08 ± 22.37 a |

| Lp VPF + S | 2.03 ± 0.52 a | 3.40 ± 1.41 a | 3.33 ± 2.36 a | 119.54 ± 12.73 b | 250.75 ± 5.46 a | 267.08 ± 7.78 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sentís-Moré, P.; Robles-Rodríguez, I.; Leonard, K.; Tchoumtchoua, J.; Escoté-Miró, X.; del Bas-Prior, J.M.; Ortega-Olivé, N. Microbial Biotransformation of Agro-Industrial Fibre-Rich By-Products into Functional Beverages. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111332

Sentís-Moré P, Robles-Rodríguez I, Leonard K, Tchoumtchoua J, Escoté-Miró X, del Bas-Prior JM, Ortega-Olivé N. Microbial Biotransformation of Agro-Industrial Fibre-Rich By-Products into Functional Beverages. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(11):1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111332

Chicago/Turabian StyleSentís-Moré, Pau, Ivan Robles-Rodríguez, Kevin Leonard, Job Tchoumtchoua, Xavier Escoté-Miró, Josep M. del Bas-Prior, and Nàdia Ortega-Olivé. 2025. "Microbial Biotransformation of Agro-Industrial Fibre-Rich By-Products into Functional Beverages" Antioxidants 14, no. 11: 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111332

APA StyleSentís-Moré, P., Robles-Rodríguez, I., Leonard, K., Tchoumtchoua, J., Escoté-Miró, X., del Bas-Prior, J. M., & Ortega-Olivé, N. (2025). Microbial Biotransformation of Agro-Industrial Fibre-Rich By-Products into Functional Beverages. Antioxidants, 14(11), 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14111332