Valorization of Onion-Processing Waste: Digestive Fate, Bioavailability, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of Red and Yellow Peels Polyphenols

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Feedstock

2.2. Polyphenol Extraction and Characterization

2.3. Evaluation of Onion Polyphenols’ Digestive Stability and Bioavailability

2.3.1. In Vitro Digestion

2.3.2. Cell Line

2.3.3. Bioavailability and Uptake of Polyphenols by Caco-2 Cells

- dC/dt (polyphenol concentration variations at different times, μg mL−1 s−1) is the appearance rate of polyphenols in the receiver compartment at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min;

- V is the volume of the receiver compartment (3 cm3);

- C0 (μg mL−1) is the initial concentration in the donor compartment;

- A is the exposed area of the tissue (4.2 cm2).

2.4. Antioxidant Activity of Onion Polyphenols

2.4.1. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity

- Asample is the absorbance at 515 nm of 20 μL of extract or standard with 180 μL DPPH solution after 40 min;

- Ablank is the absorbance at 515 nm of 20 μL of acidified EtOH 60% with 180 μL MeOH 80% after 40 min;

- Acontrol is the absorbance at 515 nm of 20 μL of acidified EtOH 60% with 180 μL DPPH solution after 40 min.

2.4.2. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

2.4.3. MTT Assay

2.4.4. Cellular Antioxidant Activity (CAA)

2.4.5. GSH Determination

2.4.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

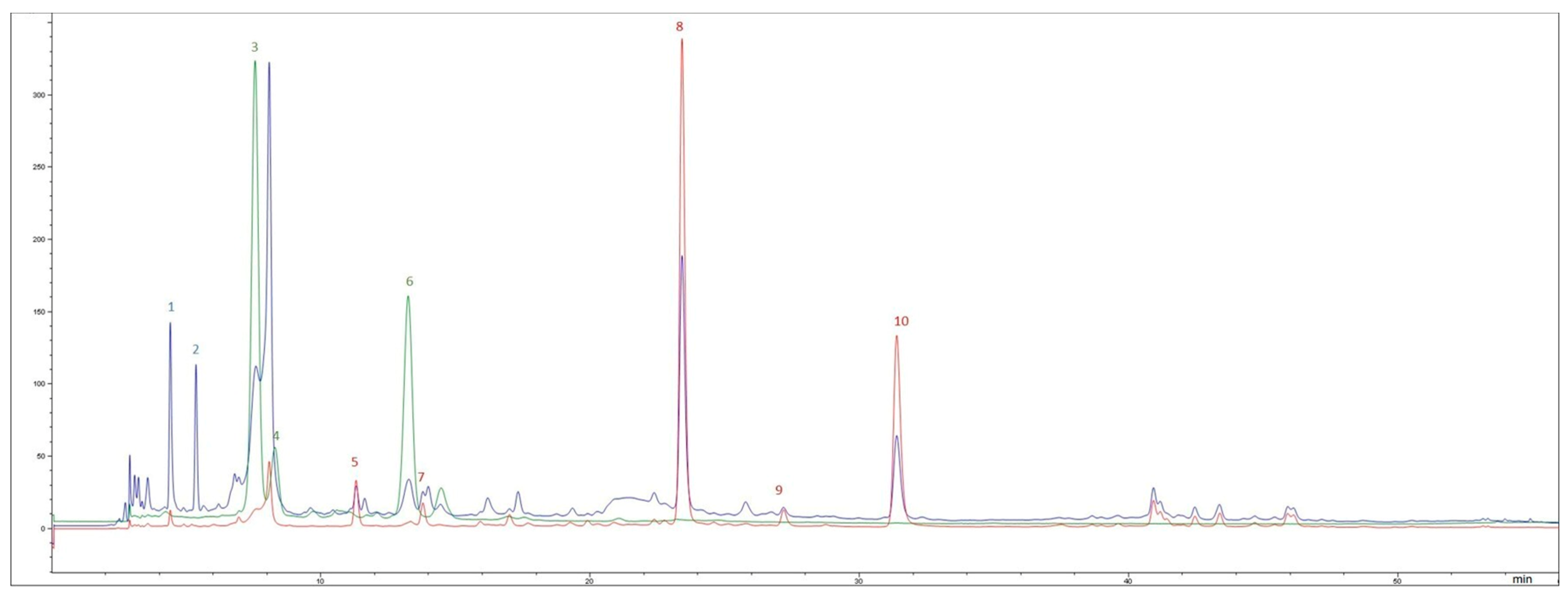

3.1. Polyphenol Characterization of Red and Yellow Onion Peels

3.2. Digestive Stability of Onion Polyphenols

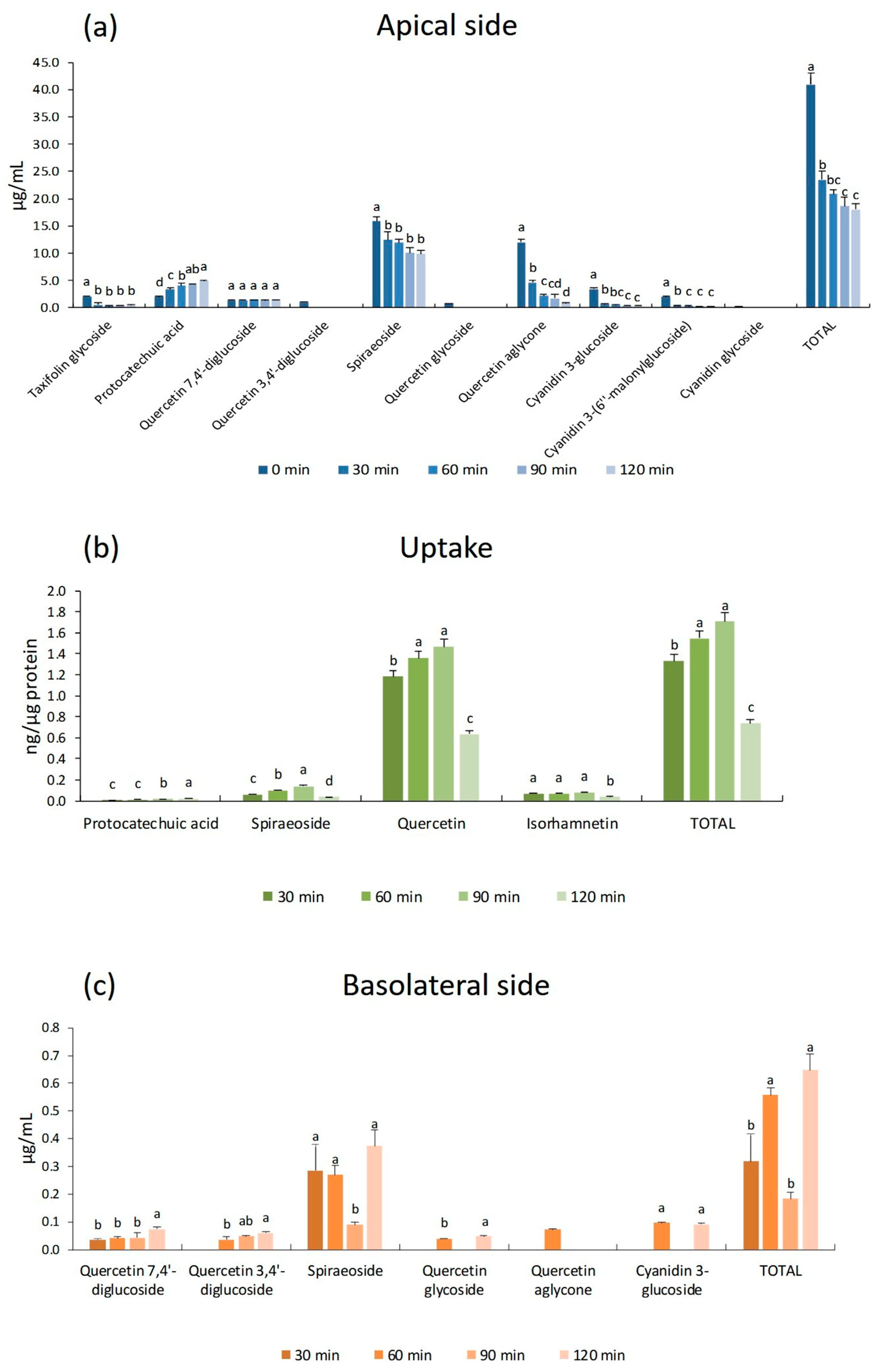

3.3. Intestinal Accumulation and Bioavailability of Red and Yellow Onion Peels’ Polyphenols

3.4. Antioxidant Activity of Red and Yellow Onion Polyphenols

3.4.1. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity and FRAP

3.4.2. Toxicity Assessment

3.4.3. Cellular Antioxidant Activity Assay

3.4.4. GSH Determination

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DPPH | 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric ion-reducing antioxidant power |

| TEER | Trans Epithelial Electrical Resistance |

| Papp | Permeability coefficient |

| TE | Trolox equivalent |

| DW | Dry weight |

| CAA | Cellular Antioxidant Activity |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Bains, A.; Sridhar, K.; Singh, B.N.; Kuhad, R.C.; Chawla, P.; Sharma, M. Valorization of onion peel waste: From trash to treasure. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Dhumal, S.; Singh, S.; Pandiselvam, R.; Rais, N.; Natta, S.; Senapathy, M.; Sinha, N.; et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: A review on the extraction of bioactive compounds, its antioxidant potential, and its application as a functional food ingredient. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4289–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Punia, S.; Dhumal, S.; Radha; Rais, N.; Chandran, D.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peels: A review on bioactive compounds and biomedical activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounir, R.; Alshareef, W.A.; El Gebaly, E.A.; El-Haddad, A.E.; Ahmed, A.M.S.; Mohamed, O.G.; Enan, E.T.; Mosallam, S.; Tripathi, A.; Selim, H.M.R.M.; et al. Unlocking the power of onion peel extracts: Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects improve wound healing through repressing Notch-1/NLRP3/Caspase-1 Signaling. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, F.A.; Bavaro, A.R.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; D’Amico, L.; Baruzzi, F.; Pinto, L.; Tarantini, A.; Garbetta, A.; Cardinali, A.; et al. Liquid submerged fermentation by selected microbial strains for onion skins valorization and its effects on polyphenols. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gregorio, R.M.; García-Falcón, M.S.; Símal-Gándara, J.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Almeida-Domingos, P.F. Identification and quantification of flavonoids in traditional cultivars of red and white onions at harvest. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.H.; Seo, J.M.; Kim, N.H.; Arasu, M.V.; Kim, S.; Yoon, M.K.; Kim, S.J. Variation of quercetin glycoside derivatives in three onion (Allium cepa L.) varieties. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marefati, N.; Ghorani, V.; Shakeri, F.; Boskabady, M.; Kianian, F.; Rezaee, R.; Boskabady, M.H. A review of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects of Allium cepa and its main constituents. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, E.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Oliveira, A.P.; Videira, R.A.; Andrade, P.B.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Onion (Allium cepa L.) skin waste valorization: Unveiling the phenolic profile and biological potential for the creation of bioactive agents through subcritical water extraction. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, D.; Lee, W.D.; Kim, S.K. Allium flavonols: Health benefits, molecular targets, and bioavailability. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Dixit, M. Role of polyphenols and other phytochemicals on molecular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 504253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbetta, A.; Capotorto, I.; Cardinali, A.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; Pizzi, F.; Minervini, F. Antioxidant activity induced by main polyphenols present in edible artichoke heads: Influence of in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbetta, A.; Nicassio, L.; D’Antuono, I.; Cardinali, A.; Linsalata, V.; Attolico, G.; Minervini, F. Influence of in vitro digestion process on polyphenolic profile of skin grape (cv. Italia) and on antioxidant activity in basal or stressed conditions of human intestinal cell line (HT-29). Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M.C.; Rahu, N. Oxidative stress and inflammation: What polyphenols can do for us? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 7432797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, A.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Mishra, V.; Aluko, R.E. Health benefits of polyphenols: A concise review. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, I.; Garbetta, A.; Linsalata, V.; Minervini, F.; Cardinali, A. Polyphenols from artichoke heads (Cynara cardunculus (L.) subsp. scolymus Hayek): In vitro bio-accessibility, intestinal uptake and bioavailability. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Dietary polyphenols impact on gut health and microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, X.; Wang, S. Health benefits of dietary polyphenols: Insight into interindividual variability in absorption and metabolism. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, A.; Linsalata, V.; Lattanzio, V.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Verbascosides from olive mill wastewater: Assessment of their bioaccessibility and intestinal uptake using an in vitro digestion/Caco-2 model system. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, H48–H54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 67, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo-García, G.; Davidov-Pardo, G.; Arroqui, C.; Vírseda, P.; Marín-Arroyo, M.R.; Navarro, M. Intra-laboratory validation of microplate methods for total phenolic content and antioxidant activity on polyphenolic extracts, and comparison with conventional spectrophotometric methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, T.; Lu, B.; Liu, R. Guidelines for antioxidant assays for food components. Food Front. 2020, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firuzi, O.; Lacanna, A.; Petrucci, R.; Marrosu, G.; Saso, L. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of flavonoids by “ferric reducing antioxidant power” assay and cyclic voltammetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1721, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, F.; Giannoccaro, A.; Cavallini, A.; Visconti, A. Investigations on cellular proliferation induced by zearalenone and its derivatives in relation to the estrogenic parameters. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 159, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Liu, R.H. Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) assay for assessing antioxidants, foods, and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8896–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celano, R.; Docimo, T.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Gazzerro, P.; Tucci, M.; Di Sanzo, R.; Carabetta, S.; Campone, L.; Russo, M.; Rastrelli, L. Onion peel: Turning a food waste into a resource. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metrani, R.; Singh, J.; Acharya, P.; K. Jayaprakasha, G.; Patil, B.S. Comparative metabolomics profiling of polyphenols, nutrients and antioxidant activities of two red onion (Allium cepa L.) cultivars. Plants 2020, 9, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paesa, M.; Nogueira, D.P.; Velderrain-Rodríguez, G.; Esparza, I.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Mendoza, G.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Valorization of onion waste by obtaining extracts rich in phenolic compounds and feasibility of its therapeutic use on colon cancer. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Pérez-Gregorio, M.R.; García-Falcón, M.S.; Simal-Gándara, J. Effect of curing and cooking on flavonols and anthocyanins in traditional varieties of onion bulbs. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, A.; Conte, A.; Martini, S.; Tagliazucchi, D. Influence of cooking methods on onion phenolic compounds bioaccessibility. Foods 2021, 10, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.; Chen, X.; Jin, Q.; Wang, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y. Comparison of phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of red and yellow onions. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, A.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Conte, A.; Martini, S.; Tagliazucchi, D. Red-skinned onion phenolic compounds stability and bioaccessibility: A comparative study between deep-frying and air-frying. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 115, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, D.; Desseva, I.; Stoyanova, M.; Petkova, N.; Terzyiska, M.; Lante, A. Impact of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on the bioaccessibility of phytochemical compounds from eight fruit juices. Molecules 2021, 26, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, J.; Xu, Z.; Wicker, L. Blueberry pectin and increased anthocyanins stability under in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2020, 302, 125343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattivelli, A.; Nissen, L.; Casciano, F.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Gianotti, A. Impact of cooking methods of red-skinned onion on metabolic transformation of phenolic compounds and gut microbiota changes. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3509–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, A.R.; Tarantini, A.; Bruno, A.; Logrieco, A.F.; Gallo, A.; Mita, G.; Valerio, F.; Bleve, G.; Cardinali, A. Functional foods in mediterranean diet: Exploring the functional features of vegetable case-studies obtained also by biotechnological approaches. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, S.M.; Bennett, R.N.; Needs, P.W.; Mellon, F.A.; Kroon, P.A.; Garcia-Conesa, M.T. Characterization of metabolites of hydroxycinnamates in the in vitro model of human small intestinal epithelium caco-2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7884–7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, M.F.; Kroon, P.A.; Williamson, G.; Garcia-Conesa, M.T. Esterase activity able to hydrolyze dietary antioxidant hydroxycinnamates is distributed along the intestine of mammals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5679–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, J.; Brown, D.; Liu, R.H. Uptake of quercetin and quercetin 3-glucoside from whole onion and apple peel extracts by Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7172–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antuono, I.; Bruno, A.; Linsalata, V.; Minervini, F.; Garbetta, A.; Tufariello, M.; Cardinali, A. Fermented Apulian table olives: Effect of selected microbial starters on polyphenols composition, antioxidant activities and bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2018, 248, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Gee, J.; Dupont, M.; Johnson, I.; Williamson, G. Absorption of quercetin-3-glucoside and quercetin-4-glucoside in the rat small intestine: The role of lactase phlorizin hydrolase and the sodium dependent glucose transporter. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 65, 119–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murota, K.; Shimizu, S.; Chujo, H.; Moon, J.H.; Terao, J. Efficiency of absorption and metabolic conversion of quercetin and its glucosides in human intestinal cell line Caco-2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 384, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Croft, K.; Ashida, H. Quercetin and its metabolite isorhamnetin promote glucose uptake through different signalling pathways in myotubes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morand, C.; Manach, C.; Crespy, V.; Remesy, C. Respective bioavailability of quercetin aglycone and its glycosides in a rat model. Biofactors 2000, 12, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Baidya, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Samanta, A.K.; Roy, S. Pharmacological basis and new insights of taxifolin: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Hassan, Y.I.; Liu, R.; Mats, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.; Tsao, R. Molecular mechanisms underlying the absorption of aglycone and glycosidic flavonoids in a Caco-2 BBe1 cell model. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10782–10793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, A.; Nile, S.H.; Cespedes-Acuña, C.L.; Oh, J.W. Spiraeoside extracted from red onion skin ameliorates apoptosis and exerts potent antitumor, antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozehnal, V.; Nakai, D.; Hoepner, U.; Fischer, T.; Kamiyama, E.; Takahashi, M.; Yasud, S.; Mueller, J. Human small intestinal and colonic tissue mounted in the Ussing chamber as a tool for characterizing the intestinal absorption of drugs. European J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 46, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, A.; Rotondo, F.; Minervini, F.; Linsalata, V.; D’Antuono, I.; Debellis, L.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Assessment of verbascoside absorption in human colonic tissues using the Ussing chamber model. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, I.; Garbetta, A.; Ciasca, B.; Linsalata, V.; Minervini, F.; Lattanzio, V.M.; Logrieco, A.F.; Cardinali, A. Biophenols from table olive cv Bella di Cerignola: Chemical characterization, bioaccessibility, and intestinal absorption. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5671–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artursson, P.; Palm, K.; Luthman, K. Caco-2 monolayers in experimental and theoretical predictions of drug transport. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 280−289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.W.; Cong, R.; Park, J.S.; Nguyen, C.H.B.; Park, K.; Kang, K.; Shim, S.M. Exploring absorption indices for a variety of polyphenols through Caco-2 cell model: Insights from permeability studies and principal component analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 6243–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bertin, R.; Froldi, G. EC50 estimation of antioxidant activity in DPPH assay using several statistical programs. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 414–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorinstein, S.; Park, Y.S.; Heo, B.G.; Namiesnik, J.; Leontowicz, H.; Leontowicz, M.; Ham, K.S.; Cho, J.Y.; Kang, S.G. A comparative study of phenolic compounds and antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in frequently consumed raw vegetables. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 228, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi, A.; El Ouardi, M.; Kaouachi, A.; Boudboud, A.; Hajji, L.; Hajjaj, H.; Mazouz, H. Characterization of the biochemical potential of Moroccan onions (Allium cepa L.). Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2021, 2103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernukha, I.; Kupaeva, N.; Kotenkova, E.; Khvostov, D. Differences in antioxidant potential of Allium cepa husk of red, yellow, and white varieties. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slimestad, R.; Fossen, T.; Vågen, I.M. Onions: A source of unique dietary flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10067–10080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzotti, V. The analysis of onion and garlic. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, G.; O’Brien, P.J. Potential toxicity of flavonoids and other dietary phenolics: Significance for their chemopreventive and anticancer properties. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.B. Natural polyphenols for prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walgren, R.A.; Walle, U.K.; Walle, T. Transport of quercetin and its glucosides across human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000, 59, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Rinna, A. Glutathione: Overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2009, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Ciriolo, M.R. Glutathione: New roles in redox signaling for an old antioxidant. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 108999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Polyphenols | Digestive Stability (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/g DW) | Gastric % | Intestinal % | |

| Phenolic acid | |||

| Protocatechuic acid | 0.52 ± 0.03 | >100.00 | >100.00 |

| Flavonoid glycosides and aglycone | |||

| Taxifolin glycoside | 0.34 ± 0.02 | >100.00 | >100.00 |

| Quercetin 7,4′-diglucoside | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 84.61 ± 0.82 a | 82.20 ± 10.42 a |

| Quercetin 3,4′-diglucoside | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 97.96 ± 0.29 a | 84.37 ± 7.76 b |

| Spiraeoside | 8.08 ± 0.40 | 99.51 ± 3.50 a | 39.97 ± 6.96 b |

| Quercetin glycoside | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 78.82 ± 3.61 a | 45.63 ± 8.60 b |

| Quercetin | 14.07 ± 0.70 | 32.34 ± 3.97 a | 15.37 ± 2.55 b |

| Anthocyanins | |||

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 1.96 ± 0.10 | 80.08 ± 4.58 a | 30.39 ± 3.91 b |

| Cyanidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | 1.65 ± 0.08 | 62.25 ± 4.45 a | 32.61 ± 1.99 b |

| Cyanidin glycoside | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 57.94 ± 2.28 a | 30.98 ± 1.86 b |

| Total identified polyphenols | 28.44 ± 1.42 | 63.39 ± 3.69 a | 49.09 ± 4.29 b |

| Polyphenols | Digestive Stability (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/g DW) | Gastric % | Intestinal % | |

| Phenolic acid | |||

| Protocatechuic acid | 2.13 ± 0.11 | 90.32 ± 4.41 b | >100.00 a |

| Flavonoid glycosides and aglycone | |||

| Taxifolin glycoside | 0.49 ± 0.02 | >100.00 | >100.00 |

| Quercetin 7,4′-diglucoside | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 90.74 ± 0.97 a | 80.06 ± 2.63 b |

| Quercetin 3,4′-diglucoside | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 97.40 ± 0.25 a | 84.42 ± 2.94 b |

| Spiraeoside | 8.35 ± 0.42 | 81.11 ± 6.54 a | 36.76 ± 3.49 b |

| Quercetin glycoside | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 69.36 ± 4.67 a | 52.52 ± 3.82 b |

| Quercetin | 2.85 ± 0.14 | 3.44 ± 0.56 b | 15.64 ± 0.96 a |

| Total identified polyphenols | 15.61 ± 0.78 | 70.92 ± 4.21 a | 72.73 ± 2.49 a |

| Red Onion Peels | Yellow Onion Peels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Polyphenols (µg/mL) | CAA Units | Total Polyphenols (µg/mL) | CAA Units |

| 30 | 84 ± 1.1 | 15 | 75 ± 1.0 |

| 12 | 76 ± 2.4 | 6 | 68 ± 3.0 |

| 6 | 68 ± 3.2 | 3 | 64 ± 3.5 |

| 3 | 58 ± 4.2 | 2 | 58 ± 2.7 |

| 2 | 50 ± 4.2 | 1.5 | 54 ± 2.5 |

| 1.5 | 48 ± 3.7 | 1.2 | 53 ± 0.2 |

| 1.2 | 43 ± 3.4 | 1.0 | 50 ± 0.8 |

| 1 | 42 ± 1.3 | 0.8 | 44 ± 3.9 |

| 0.9 | 40 ± 4.5 | 0.6 | 42 ± 3.4 |

| MED 1.69 ± 0.42 µg/mL | MED 1.03 ± 0.23 µg/mL | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bavaro, A.R.; D’Antuono, I.; Bruno, A.; Ramires, F.A.; Linsalata, V.; Bleve, G.; Cardinali, A.; Garbetta, A. Valorization of Onion-Processing Waste: Digestive Fate, Bioavailability, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of Red and Yellow Peels Polyphenols. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010007

Bavaro AR, D’Antuono I, Bruno A, Ramires FA, Linsalata V, Bleve G, Cardinali A, Garbetta A. Valorization of Onion-Processing Waste: Digestive Fate, Bioavailability, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of Red and Yellow Peels Polyphenols. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleBavaro, Anna Rita, Isabella D’Antuono, Angelica Bruno, Francesca Anna Ramires, Vito Linsalata, Gianluca Bleve, Angela Cardinali, and Antonella Garbetta. 2026. "Valorization of Onion-Processing Waste: Digestive Fate, Bioavailability, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of Red and Yellow Peels Polyphenols" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010007

APA StyleBavaro, A. R., D’Antuono, I., Bruno, A., Ramires, F. A., Linsalata, V., Bleve, G., Cardinali, A., & Garbetta, A. (2026). Valorization of Onion-Processing Waste: Digestive Fate, Bioavailability, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of Red and Yellow Peels Polyphenols. Antioxidants, 15(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010007