Effect of Dietary PUFAs and Antioxidants on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of HDL in a Cohort of Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Biochemical Analysis

2.2.1. Metabolic Markers

2.2.2. PON1-Arylesterase Activity

2.2.3. PON1-Lactonase Activity

2.2.4. Lp-PLA2 Activity

2.2.5. GPX3 Activity

2.2.6. MPO Activity

2.2.7. Total MPO Protein Concentration

2.2.8. Oxidized HDL

2.3. HDL-Antioxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Score (HDL-AAS)

2.4. Nutritional Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Main Characteristics of the Study Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pappa, E.; Elisaf, M.S.; Kostara, C.; Bairaktari, E.; Tsimihodimos, V.K. Cardioprotective Properties of HDL: Structural and Functional Considerations. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 2964–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieko Mineo, P.; Philip, W.; Shaul, M.D. Novel Biological Functions of HDL Cholesterol. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R.; Dousset, N.; Curatola, G. Structural Modifications of HDL and Functional Consequences. Atherosclerosis 2006, 184, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, W.S.; Shah, A.S.; Sexmith, H.; Gordon, S.M. The HDL Proteome Watch: Compilation of Studies Leads to New Insights on HDL Function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimetti, F.; De Vuono, S.; Gomaraschi, M.; Adorni, M.P.; Favari, E.; Ronda, N.; Ricci, M.A.; Veglia, F.; Calabresi, L.; Lupattelli, G. Plasma Cholesterol Homeostasis, HDL Remodeling and Function during the Acute Phase Reaction. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimetti, F.; Adorni, M.P.; Marsillach, J.; Marchi, C.; Trentini, A.; Valacchi, G.; Cervellati, C. Connection between the Altered HDL Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties and the Risk to Develop Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6695796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A.; Vigna, G.B.; Romani, A.; Sanz, J.M.; Cavicchio, C.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Valacchi, G.; Cervellati, C. Distribution of Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) and Lipoprotein Phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) across Lipoprotein Subclasses in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1752940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervellati, C.; Vigna, G.B.; Trentini, A.; Sanz, J.M.; Zimetti, F.; Dalla Nora, E.; Morieri, M.L.; Zuliani, G.; Passaro, A. Paraoxonase-1 Activities in Individuals with Different HDL Circulating Levels: Implication in Reverse Cholesterol Transport and Early Vascular Damage. Atherosclerosis 2019, 285, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria-Florido, M.T.; Schröder, H.; Grau, M.; Fitó, M.; Lassale, C. High Density Lipoprotein Functionality and Cardiovascular Events and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Atherosclerosis 2020, 302, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Aicha, S.; Badimon, L.; Vilahur, G. Advances in HDL: Much More than Lipid Transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren-Gluzer, M.; Aviram, M.; Meilin, E.; Hayek, T. The Antioxidant HDL-Associated Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) Attenuates Diabetes Development and Stimulates β-Cell Insulin Release. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Variji, A.; Shokri, Y.; Fallahpour, S.; Zargari, M.; Bagheri, B.; Abediankenari, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Mahrooz, A. The Combined Utility of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) as Two Important HDL-Associated Enzymes in Coronary Artery Disease: Which Has a Stronger Predictive Role? Atherosclerosis 2019, 280, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsillach, J.; Adorni, M.P.; Zimetti, F.; Papotti, B.; Zuliani, G.; Cervellati, C. HDL Proteome and Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence of a Link. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentini, A.; Rosta, V.; Spadaro, S.; Bellini, T.; Rizzo, P.; Vieceli Dalla Sega, F.; Passaro, A.; Zuliani, G.; Gentili, V.; Campo, G.; et al. Development, Optimization and Validation of an Absolute Specific Assay for Active Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and Its Application in a Clinical Context: Role of MPO Specific Activity in Coronary Artery Disease. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2020, 58, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J.; Cervellati, C.; Crivellari, I.; Pecorelli, A.; Valacchi, G. Lactonase Activity and Lipoprotein-Phospholipase A2as Possible Novel Serum Biomarkers for the Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders and Rett Syndrome: Results from a Pilot Study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 5694058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shi, T.; Lu, K.; Qian, D.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, J.; et al. Influence of Lecithin Cholesterol Acyltransferase Alteration during Different Pathophysiologic Conditions: A 45 Years Bibliometrics Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1062249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Chen, X.; Nasr, A.; Billheimer, J.; Brooks, M.M.; McConnell, D.; Orchard, T.J.; Crawford, S.L.; Matthews, K.A.; Rader, D.J. HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) Subclasses, Lipid Content, and Function Trajectories Across the Menopause Transition. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Wang, L.; Brooks, M.M.; Thurston, R.C.; Derby, C.A.; Matthews, K.A. Increase HDL-C Level over the Menopausal Transition Is Associated with Greater Atherosclerotic Progression. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2016, 10, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce-Ruiz, N.; Murillo-González, F.E.; Rojas-García, A.E.; Bernal Hernández, Y.Y.; Mackness, M.; Ponce-Gallegos, J.; Barrón-Vivanco, B.S.; Hernández-Ochoa, I.; González-Arias, C.A.; Ortega Cervantes, L.; et al. Phenotypes and Concentration of PON1 in Cardiovascular Disease: The Role of Nutrient Intake. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauerer, R.; Ebert, S.; Langmann, T. High Glucose, Unsaturated and Saturated Fatty Acids Differentially Regulate Expression of ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in Human Macrophages. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009, 41, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Etherton, T.D.; Martin, K.R.; Vanden Heuvel, J.P.; Gillies, P.J.; West, S.G.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in THP-1 Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 336, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of Docosahexaenoic Supplementation and In Vitro Vitamin C on the Oxidative and Inflammatory Neutrophil Response to Activation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 187849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.X.; Weylandt, K.H. Modulation of Inflammatory Cytokines by Omega-3 Fatty Acids. In Lipids in Health and Disease; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hernáez, Á.; Castañer, O.; Elosua, R.; Pintó, X.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Serra-Majem, L.; Fiol, M.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Improves High-Density Lipoprotein Function in High-Cardiovascular-Risk Individuals. Circulation 2017, 135, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Agostoni, C.; Visioli, F. Dietary Fatty Acids and Inflammation: Focus on the n-6 Series. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, M.; Clifton, P.; Kestin, M.; Belling, B.; Nestel, P. Effect of Fish Oil on Lipoproteins, Lecithin:Cholesterol Acyltransferase, and Lipid Transfer Protein Activity in Humans. Arterioscler. Off. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Inc. 1990, 10, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.-L.; Eric Paulson, K.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Lamon-Fava, S. Regulation of the Expression of Key Genes Involved in HDL Metabolism by Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, C.J.; Mayr, H.L.; Lohning, A.E.; Reidlinger, D.P. The Association between Dietary Patterns and the Novel Inflammatory Markers Platelet-Activating Factor and Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1371–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumalla-Cano, S.; Eguren-García, I.; Lasarte-García, Á.; Prola, T.; Martínez-Díaz, R.; Elío, I. Carotenoids Intake and Cardiovascular Prevention: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, A.M.; Anderson, J.D.; Meyer, C.H.; Epstein, F.H.; Wang, H.; Hagspiel, K.D.; Berr, S.S.; Harthun, N.L.; DiMaria, J.M.; Hunter, J.R.; et al. The Effect of Ezetimibe on Peripheral Arterial Atherosclerosis Depends upon Statin Use at Baseline. Atherosclerosis 2011, 218, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarandol, E.; Dirican, M.; Ocak, N.; Serdar, Z.; Sonmezisik, F.; Dilek, K. The Effects of Vitamin E-Coated Dialysis Membranes on Serum Paraoxonase Activity in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Nephrol. 2010, 23, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, S.D.; Gass, M.; Hall, J.E.; Lobo, R.; Maki, P.; Rebar, R.W.; Sherman, S.; Sluss, P.M.; de Villiers, T.J. Executive Summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10. Menopause 2012, 19, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, A.A.; Matin, A.A.; Hadwan, M.H.; Hadwan, A.M.; Mohammed, R.M. Rapid and Effective Protocol to Measure Glutathione Peroxidase Activity. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Roy, S.; Nguyen, H.C.X.; Angelovich, T.A.; Hearps, A.C.; Huynh, D.; Jaworowski, A.; Kelesidis, T. Cell-Free Biochemical Fluorometric Enzymatic Assay for High-Throughput Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation in High Density Lipoprotein. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 128, e56325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, C.L.; Chirita-Emandi, A.; Perva, I.T.; Sima, A.; Andreescu, N.; Putnoky, S.; Niculescu, M.D.; Puiu, M. Intake Differences between Subsequent 24-h Dietary Recalls Create Significant Reporting Bias in Adults with Obesity. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.G.; Vitalone, A.; Cole, T.B.; Furlong, C.E. Modulation of Paraoxonase (PON1) Activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 69, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, O.; Rosenblat, M.; Coleman, R.; Shih, D.M.; Aviram, M. Paraoxonase (PON1) Deficiency Is Associated with Increased Macrophage Oxidative Stress: Studies in PON1-Knockout Mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, M.; Gaidukov, L.; Khersonsky, O.; Vaya, J.; Oren, R.; Tawfik, D.S.; Aviram, M. The Catalytic Histidine Dyad of High Density Lipoprotein-Associated Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) Is Essential for PON1-Mediated Inhibition of Low Density Lipoprotein Oxidation and Stimulation of Macrophage Cholesterol Efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 7657–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vorst, E.P.C. High-Density Lipoproteins and Apolipoprotein A1; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 94, ISBN 9783030417697. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellati, C.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Trentini, A.; Valacchi, G.; Sanz, J.M.; Squerzanti, M.; Spagnolo, M.; Massari, L.; Crivellari, I.; Greco, P.; et al. Paraoxonase, Arylesterase and Lactonase Activities of Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) in Obese and Severely Obese Women. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2018, 78, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Trentini, A.; Marsillach, J.; D’Amuri, A.; Bosi, C.; Roncon, L.; Passaro, A.; Zuliani, G.; Mackness, M.; Cervellati, C. Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) Arylesterase Activity Levels in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 4264314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, T.; Fuhrman, B.; Vaya, J.; Rosenblat, M.; Belinky, P.; Coleman, R.; Elis, A.; Aviram, M. Reduced Progression of Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice Following Consumption of Red Wine, or Its Polyphenols Quercetin or Catechin, Is Associated with Reduced Susceptibility of LDL to Oxidation and Aggregation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 2744–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, D.M.; Gu, L.; Hama, S.; Xia, Y.R.; Navab, M.; Fogelman, A.M.; Lusis, A.J. Genetic-Dietary Regulation of Serum Paraoxonase Expression and Its Role in Atherogenesis in a Mouse Model. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sutherland, W.H.F.; Walker, R.J.; de Jong, S.A.; van Rij, A.M.; Phillips, V.; Walker, H.L. Reduced Postprandial Serum Paraoxonase Activity After a Meal Rich in Used Cooking Fat. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, J.; Marsillach, J.; Joven, J. The Paraoxonases: Role in Human Diseases and Methodological Difficulties in Measurement. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009, 46, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, J.J.; Tecles, F.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. Serum Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Measurement: An Update. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teiber, J.F.; Draganov, D.I.; La Du, B.N. Lactonase and Lactonizing Activities of Human Serum Paraoxonase (PON1) and Rabbit Serum PON3. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, C.; Cubedo, J.; Padró, T.; Sánchez-Hernández, J.; Antonijoan, R.; Perez, A.; Badimon, L. Phytosterols and Omega 3 Supplementation Exert Novel Regulatory Effects on Metabolic and Inflammatory Pathways: A Proteomic Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppedisano, F.; Macrì, R.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Bosco, F.; Nucera, S.; Caterina Zito, M.; Guarnieri, L.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariamenatu, A.H.; Abdu, E.M. Overconsumption of Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) versus Deficiency of Omega-3 PUFAs in Modern-Day Diets: The Disturbing Factor for Their “Balanced Antagonistic Metabolic Functions” in the Human Body. J. Lipids 2021, 2021, 8848161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, M.; Rosenblat, M.; Billecke, S.; Erogul, J.; Sorenson, R.; Bisgaier, C.L.; Newton, R.S.; La Du, B. Human Serum Paraoxonase (PON 1) Is Inactivated by Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein and Preserved by Antioxidants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.D.; Hung, N.D.; Cheon-Ho, P.; Ree, K.M.; Dai-Eun, S. Oxidative Inactivation of Lactonase Activity of Purified Human Paraoxonase 1 (PON1). Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossoli, A.; Pavanello, C.; Calabresi, L. High-Density Lipoprotein, Lecithin: Cholesterol Acyltransferase, and Atherosclerosis. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 31, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norum, K.R.; Remaley, A.; Miettinen, H.E.; Strøm, E.H.; Balbo, B.E.P.; Sampaio, C.A.T.L.; Wiig, I.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; Calabresi, L.; Tesmer, J.J.; et al. Lecithin:Cholesterol Acyltransferase: Symposium on 50 Years of Biomedical Research from Its Discovery to Latest Findings. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Worley, B.L.; Phaëton, R.; Hempel, N. Extracellular Glutathione Peroxidase GPx3 and Its Role in Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.S.; Kim, M.; Youn, B.-S.; Lee, N.S.; Park, J.W.; Lee, I.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.B.; Cho, Y.M.; Lee, H.K.; et al. Glutathione Peroxidase 3 Mediates the Antioxidant Effect of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.T.; Lakshmi, S.P.; Banno, A.; Reddy, R.C. Role of GPx3 in PPARγ-Induced Protection against COPD-Associated Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 126, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman, M.P. Selenium and Human Health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Zweier, J.L.; Li, Y. Role of Nrf2 Signaling in Regulation of Antioxidants and Phase 2 Enzymes in Cardiac Fibroblasts: Protection against Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species-Induced Cell Injury. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 3029–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, S.; Arora, R. Utility of Lp-PLA2 in Lipid-Lowering Therapy. Am. J. Ther. 2012, 19, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, M.; Nilsson, J.-Å.; Nelson, J.J.; Hedblad, B.; Berglund, G. The Epidemiology of Lp-PLA2: Distribution and Correlation with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Population-Based Cohort. Atherosclerosis 2007, 190, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, D.; Herrmann, J.; Versari, D.; Gössl, M.; Meyer, F.B.; McConnell, J.P.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Enhanced Expression of Lp-PLA2 and Lysophosphatidylcholine in Symptomatic Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaques. Stroke 2008, 39, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podrez, E.A.; Schmitt, D.; Hoff, H.F.; Hazen, S.L. Myeloperoxidase-Generated Reactive Nitrogen Species Convert LDL into an Atherogenic Form In Vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, D.L.; Mone, J.; Lefkowitz, S.S. Myeloperoxidase: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 6, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.-C.; Hou, Y.-C.; Yeh, C.-L.; Hu, Y.-M.; Yeh, S.-L. Effect of Dietary Fish Oil Supplementation on Cellular Adhesion Molecule Expression and Tissue Myeloperoxidase Activity in Diabetic Mice with Sepsis. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althurwi, H.N.; Abdel-Rahman, R.F.; Soliman, G.A.; Ogaly, H.A.; Alkholifi, F.K.; Abd-Elsalam, R.M.; Alqasoumi, S.I.; Abdel-Kader, M.S. Protective Effect of Beta-Carotene against Myeloperoxidase- Mediated Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Rat Ischemic Brain Injury. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Quintanar, L.; Funes, L.; Herranz-López, M.; Martínez-Peinado, P.; Pascual-García, S.; Sempere, J.M.; Boix-Castejón, M.; Córdova, A.; Pons, A.; Micol, V.; et al. Antioxidant Supplementation Modulates Neutrophil Inflammatory Response to Exercise-Induced Stress. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Tamimi, R.M.; Hankinson, S.E.; Hunter, D.J.; Han, J. A Prospective Study of Genetic Polymorphism in MPO, Antioxidant Status, and Breast Cancer Risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 113, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, F.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Incerpi, S.; Belli, S.; Sakib, R.; Rossi, M. Interaction between Vitamins C and E When Scavenging the Superoxide Radical Shown by Hydrodynamic Voltammetry and DFT. Biophysica 2024, 4, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, I.; Decker, E.A. Underlying Mechanisms of Synergistic Antioxidant Interactions during Lipid Oxidation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.; de Serna, D.G.; Gutierrez, A.; Schade, D.S. Vitamin E in Humans: An Explanation of Clinical Trial Failure. Endocr. Pract. 2006, 12, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; Thomassen, A.S.; Mashaw, S.A.; MacDonald, E.M.; Waguespack, A.; Hickey, L.; Singh, A.; Gungor, D.; Kallurkar, A.; Kaye, A.M.; et al. Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol): Emerging Clinical Role and Adverse Risks of Supplementation in Adults. Cureus 2025, 17, e78679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, P.; Wan, S.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, S.; Xu, T.; He, J.; Mechanick, J.I.; Wu, W.-C.; et al. Micronutrient Supplementation to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2269–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Deng, H.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Lin, J.; Zheng, P.; Ji, G. Vitamin E for People with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 16, CD015033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.A.; Evans, C.V.; Ivlev, I.; Rushkin, M.C.; Thomas, R.G.; Martin, A.; Lin, J.S. Vitamin and Mineral Supplements for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. JAMA 2022, 327, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Na, X.; Zhao, A. β-Carotene Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, R.P.; Zock, P.L.; Kester, A.D.; Katan, M.B. Effects of Dietary Fatty Acids and Carbohydrates on the Ratio of Serum Total to HDL Cholesterol and on Serum Lipids and Apolipoproteins: A Meta-Analysis of 60 Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreuder, Y.J.; Hutten, B.A.; van Eijsden, M.; Jansen, E.H.; Vissers, M.N.; Twickler, M.T.; Vrijkotte, T.G.M. Ethnic Differences in Maternal Total Cholesterol and Triglyceride Levels during Pregnancy: The Contribution of Demographics, Behavioural Factors and Clinical Characteristics. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwich, J.; Leszczynska-Golabek, I.; Kiec-Wilk, B.; Siedlecka, D.; Pérez-Martinez, P.; Marin, C.; López-Miranda, J.; Tierney, A.; Monagle, J.M.; Roche, H.M.; et al. Lipoprotein Profile, Plasma Ischemia Modified Albumin and LDL Density Change in the Course of Postprandial Lipemia. Insights from the LIPGENE Study. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2010, 70, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.; Wall, R.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Health Implications of High Dietary Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 539426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli, A.; Cervellati, C.; Cordone, V.; Amicarelli, F.; Hayek, J.; Valacchi, G. 13-HODE, 9-HODE and ALOX15 as Potential Players in Rett Syndrome OxInflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 134, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämmerer, I.; Ringseis, R.; Biemann, R.; Wen, G.; Eder, K. 13-Hydroxy Linoleic Acid Increases Expression of the Cholesterol Transporters ABCA1, ABCG1 and SR-BI and Stimulates ApoA-I-Dependent Cholesterol Efflux in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisar, T.; Wang, S.; Omer, M.; Irwin, A.D.; Storey, C.; Tang, C.; den Hartigh, L.J. 10,12-Conjugated Linoleic Acid Supplementation Improves HDL Composition and Function in Mice. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marklund, M.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Imamura, F.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Fretts, A.; de Goede, J.; Shi, P.; Tintle, N.; Wennberg, M.; Aslibekyan, S.; et al. Biomarkers of Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Circulation 2019, 139, 2422–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, R.; Norouzzadeh, M.; HasanRashedi, M.; Jamshidi, S.; Ahmadirad, H.; Alemrajabi, M.; Vafa, M.; Teymoori, F. Dietary and Circulating Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer Risk, and Mortality: A Global Meta-Analysis of 150 Cohorts and Meta-Regression. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblat, M.; Karry, R.; Aviram, M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Is a More Potent Antioxidant and Stimulant of Macrophage Cholesterol Efflux, When Present in HDL than in Lipoprotein-Deficient Serum: Relevance to Diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2006, 187, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.Y.; Tang, C.; Guevara, M.E.; Wei, H.; Wietecha, T.; Shao, B.; Subramanian, S.; Omer, M.; Wang, S.; O’Brien, K.D.; et al. Serum Amyloid A Impairs the Antiinflammatory Properties of HDL. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Number | 145 |

| Age, years | 52 ± 7 |

| Postmenopausal status, n (%) | 74 (50) |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 25 (23–28) |

| |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 22, (15) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 20, (14) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 9 (6) |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 35 (24) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 10 (7) |

| |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 66 ± 14 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 148 ± 33 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 76 (60–103) |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 231 ± 37 |

| ApoA1, mg/dL | 176 ± 33 |

| ApoB, mg/dL | 92 ± 18 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 94 (90–100) |

| Insulin, mg/dL | 5 (3–8) |

| HOMA-IR index | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| |

| PON1-arylesterase, U/L | 92 ± 20 |

| PON1-Lactonase activity, U/L | 85 ± 19 |

| Gpx3, U/L | 183 ± 28 |

| Lp-PLA2, U/L | 12.8 ± 2.9 |

| L-CAT, arbitrary units | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) |

| Ox-HDL, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| MPO-concentration, mg/dL | 0.77 (0.59–1.29) |

| MPO-activity, U/L | 0.01 (0.01–0.03) |

| MPO-specific activity, U/µg | 0.15 (0.10–0.25) |

| Nutrients | |

|---|---|

| Calories, Kcal/day | 1993 ± 391 |

| Proteins, g/day | 86 ± 17 |

| Lipids, g/day | 89 ± 19 |

| Fiber, g/day | 19 ± 5 |

| |

| Saturated FA, g/day | 22 (17–27) |

| Unsaturated FA, g/day | 6.5 (3.4–8.5) |

| Saturated FA/unsaturated FA | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) |

| MUFA, g/day | 0.02 ± 0.004 |

| PUFA, g/day | 8.5 (7–11) |

| Omega-3, g/day | 1.0 (0.7–1.7) |

| Omega-6, g/day | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) |

| Omega-6/omega-3 | 4.6 (3.8–6.8) |

| |

| Vitamin A, µg/day | 1181 (867–1444) |

| Vitamin E, mg/day | 15 (12–17) |

| Vitamin C, µg/day | 183 (128–227) |

| B-carotenoid, mg/day | 134 (49–520) |

| Selenium, µg/day | 31 (22–51) |

| Zinc, µg/day | 11 (8–13) |

| Polyphenols, mg/day | 428 ± 189 |

| H-ORAC, µmoles/day | 3204 (1162–6250) |

| L-ORAC, µmoles/day | 68 (15–154) |

| Total ORAC, µmoles/day | 3235 (1183–6238) |

| Lp-PLA2 Activity | PON1 Arylesterase Activity | PON1 Lactonase Activity | MPO Activity | MPO Concentration | MPO-Specific Activity | GPx3 Activity | LCAT Activity | oxHDL | APOA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated FA | 0.035 | −0.075 | −0.117 | −0.076 | * 0.156 | −0.112 | −0.031 | −0.028 | 0.1 | 0.055 |

| PUFA | 0.056 | 0.035 | −0.1 | −0.184 * | −0.123 | −0.288 | 0.073 | −0.06 | 0.034 | 0.123 |

| MUFA | 0.069 | −0.079 | −0.177 | 0.046 | −0.121 | −0.118 | 0.111 | −0.22 | 0.004 | 0.075 |

| Unsaturated FA tot | −0.021 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.01 | −0.058 | −0.089 | 0.165 | −0.015 | 0.113 | −0.035 |

| Saturated/unsaturated | 0.035 | −0.041 | −0.056 | −0.04 | 0.023 | 0.05 | −0.166 | 0.005 | −0.08 | 0.055 |

| Omega−3 | −0.03 | −0.111 | −0.128 | −0.158 * | −0.105 | −0.265 ** | 0.219 * | −0.036 | 0.063 | 0.088 |

| Omega−6 | 0.046 | 0.108 | −0.171 * | −0.212 * | −0.129 | −0.224 * | −0.042 | −0.003 | −0.088 | 0.247 * |

| Omega−6/omega−3 | 0.059 | 0.189 | 0.154 | −0.018 | −0.08 | 0.096 | −0.145 | −0.002 | −0.122 | 0.05 |

| Alpha-Tocopherol | −0.034 | 0.025 | −0.031 | 0.028 | −0.121 | −0.190 * | 0.196 | 0.181 | 0.049 | −0.06 |

| Vitamin A | −0.057 | −0.195 * | −0.12 | 0.091 | −0.122 | −0.186 * | 0.082 | −0.12 | 0.16 | −0.034 |

| Vitamin C | 0.05 | −0.096 | −0.099 | 0.058 | −0.109 | −0.175 * | 0.119 | −0.063 | 0.144 | 0.091 |

| Beta-cartotene | −0.081 | −0.067 | −0.025 | −0.077 | −0.123 | −0.094 | 0.123 | 0.186 * | 0.162 | −0.099 |

| Polyphenols | −0.141 | 0.101 | 0.149 | −0.218 ** | −0.192 * | −0.170 * | 0.081 | 0.068 | 0.02 | 0.114 |

| Selenium | −0.033 | −0.092 | −0.06 | 0.129 | −0.123 | −0.101 | 0.175 | −0.037 | 0.086 | −0.025 |

| H-ORAC | −0.253 * | 0.086 | 0.151 | −0.233 * | −0.187 * | −0.173 | 0.203 * | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.116 |

| L-ORAC | −0.064 | 0.038 | −0.045 | −0.218 * | −0.150 | −0.187 | 0.238 * | −0.027 | 0.092 | 0.046 |

| Total-ORAC | −0.249 * | 0.084 | 0.151 | −0.235 * | −0.188 * | −0.175 | 0.206 * | 0.004 | 0.028 | 0.115 |

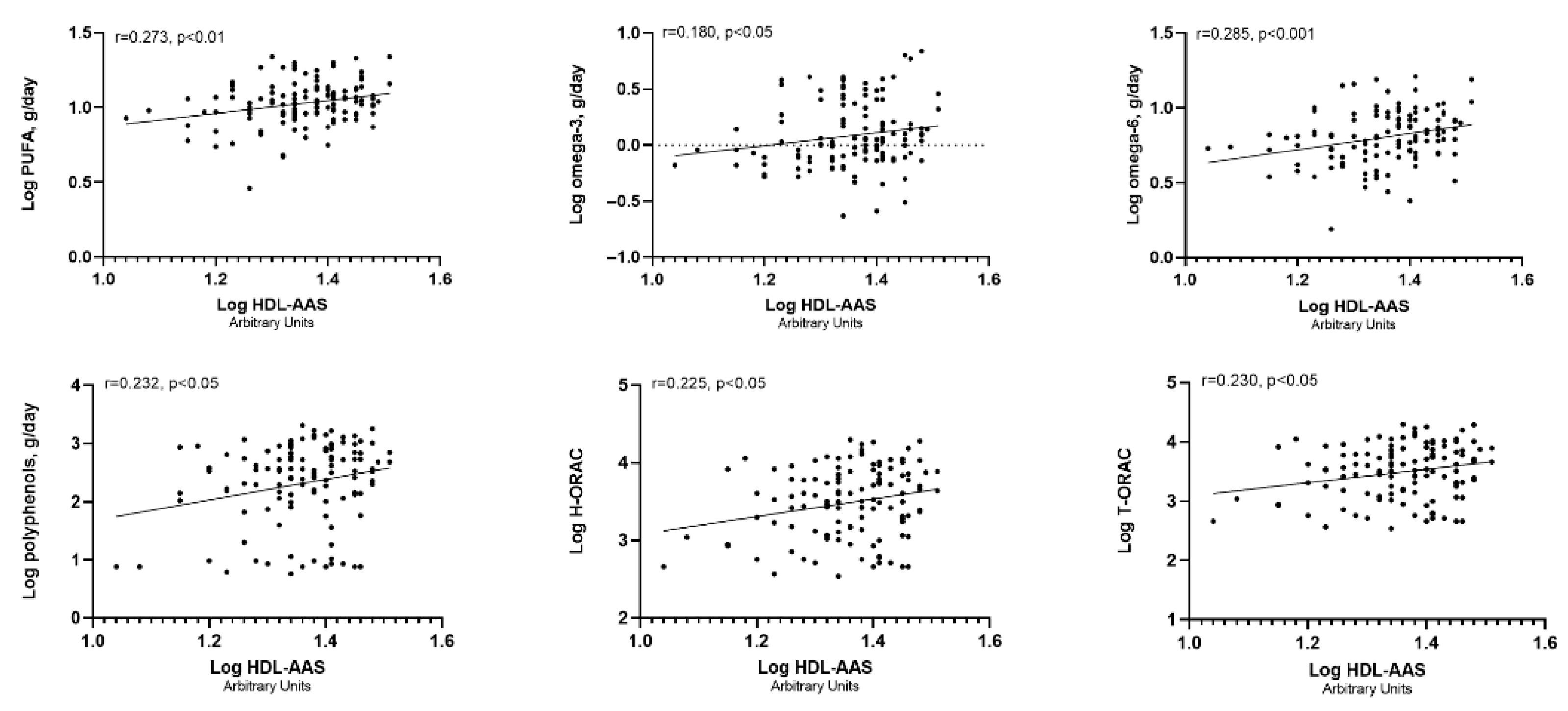

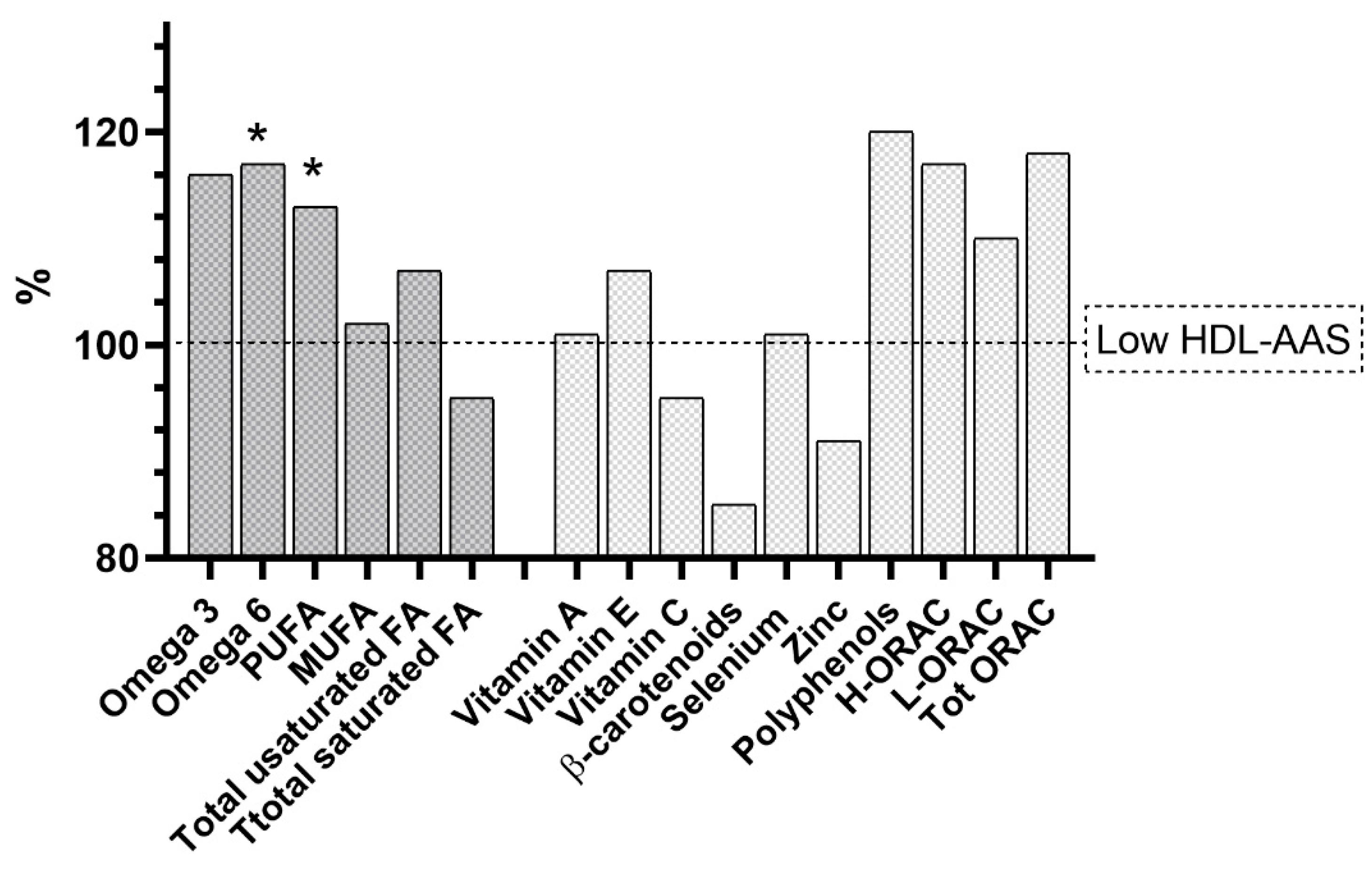

| Explanatory Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standard Error | Standardized Coefficients (β) | Adjusted R2 # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUFA | 8.94 | 2.48 | 0.289 *** | 0.204 *** |

| Omega-3 | 3.136 | 1.284 | 0.201 ** | 0.160 * |

| Omega-6 | 6.895 | 2.097 | 0.267 *** | 0.191 ** |

| Polyphenols | 1.352 | 0.532 | 0.212 * | 0.179 ** |

| H-ORAC | 2.121 | 0.825 | 0.215 * | 0.160 * |

| T-ORAC | 2.164 | 0.828 | 0.220 * | 0.161 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mola, G.; Riccetti, R.; Sergi, D.; Trentini, A.; Rosta, V.; Passaro, A.; Sanz, J.M.; Cervellati, C. Effect of Dietary PUFAs and Antioxidants on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of HDL in a Cohort of Women. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14101221

Mola G, Riccetti R, Sergi D, Trentini A, Rosta V, Passaro A, Sanz JM, Cervellati C. Effect of Dietary PUFAs and Antioxidants on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of HDL in a Cohort of Women. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(10):1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14101221

Chicago/Turabian StyleMola, Gianmarco, Raffaella Riccetti, Domenico Sergi, Alessandro Trentini, Valentina Rosta, Angelina Passaro, Juana M. Sanz, and Carlo Cervellati. 2025. "Effect of Dietary PUFAs and Antioxidants on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of HDL in a Cohort of Women" Antioxidants 14, no. 10: 1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14101221

APA StyleMola, G., Riccetti, R., Sergi, D., Trentini, A., Rosta, V., Passaro, A., Sanz, J. M., & Cervellati, C. (2025). Effect of Dietary PUFAs and Antioxidants on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of HDL in a Cohort of Women. Antioxidants, 14(10), 1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14101221