3.1. Phenolic Profile as a Function of Cultivar, Environmental Conditions, and Harvest Period

Phenolic alcohols and secoiridoids are considered to be the main phenolic group of compounds, while phenolic acids, flavonoids, and lignans have also been identified in VOOs playing various significant and synergistic roles [

7,

41,

42].

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the phenolic composition of the studied monocultivar VOOs, which differed significantly among the examined cultivars (except for tyrosol, vanillic acid, dialdehyde form of decarboxymethyl ligstroside aglycone, apigenin). The dialdehyde form of decarboxymethyloleuropein aglycone (DMOdA) (Oblica 78.8–277.2 mg kg

−1; Leccino 60.6–347.9 mg kg

−1) and the dialdehyde form of decarboxymethyl ligstroside aglycone (DMLdA) (Oblica 85.1–166.5 mg kg

−1; Leccino 32.9–142.7 mg kg

−1) were the most abundant phenolic compounds in both monocultivar oils (

Table 1 and

Table 2), consistent with previously published studies for other VOOs [

20,

43]. The average content of hydroxytyrosol in Oblica oils was 6.2 mg kg

−1 being significantly higher than in Leccino VOOs (average 4.0 mg kg

−1). For lignans, a significant higher pinoresinol concentration was found in Oblica compared to Leccino VOOs, which could be a cultivar characteristic according to Brenes et al. [

44].

The evaluation of the phenolic composition of VOO from two growing seasons and different geographical sites (Kaštela and Šestonovac) revealed significant differences (

p ≤ 0.05) between seasons and sites. Differences in phenolic compound concentrations between VOO from two growing seasons were less pronounced in Oblica (

Table 1) than in Leccino VOOs (concentrations were up to two times higher) (

Table 2). Some researchers point out that growing season is a factor that leads to a difference in phenolic content in other monocultivar VOOs [

45,

46]. This is most likely due to the different climatic conditions that prevail in a given year. Accordingly, using correlations useful for indicating a predictive relationship that can be applied in practice, a significant relationship between precipitation and mean daily temperature (

Table S1) was found with the concentration of phenolic compounds (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

During the period of intensive olive fruit growth precipitation correlated positively with the concentration of phenolic alcohols, flavonoids (luteolin) and secoiridoids (OAgl-A, OA-dA), while it correlated negatively with phenolic acids (

Table 3). The negative correlation of precipitation with seven phenolic compounds was observed in the period of fruit ripening with the strongest correlation with total secoiridoids content (TSC). In 2011, the July–August period was wetter than the same period in 2012 (166.2 and 216.6 mm, 44.6 and 61.1 mm; 2011 and 2012 for Kaštela and Šestanovac, respectively;

Table S1), while olive received more water in the ripening period in 2012 (256.0 and 207.3 mm, 317.6 and 220.7 mm; 2011 and 2012 for Kaštela and Šestanovac, respectively;

Table S1). The literature suggests that water availability affects the groups of phenolic compounds to varying degrees, with the greatest changes observed in the proportions of compounds from the secoiridoids group [

47]. In the present study (

Table 3), phenolic acids were found to be most affected by precipitation during the observation period (the correlation was significant in 10 cases out of 20 pairs studied). However, since we know the importance of secoiridoids and this group is the most abundant; it is noteworthy to timepiece their behavior. For Oblica VOOs, TSC differed only about 2% between growing seasons and was higher in 2011 (

Table 1). Larger differences (about 20%) and higher TOS values in 2012 were observed in Leccino VOOs (

Table 2). Within the individual fractions of secoiridoids, the highest difference between two growing seasons studied was 9% in Oblica VOOs, while in Leccino VOOs the concentrations of DMOdA and OAgl-A differed by 50% between seasons (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Water availability is considered as an essential parameter for phenol synthesis [

19,

48,

49,

50] by affecting (under the stress conditions) the activity of L-phenylalanine ammonium lyase [

51], which most likely represents the agronomic traits of a cultivar [

52,

53]. Thus, the different responses of two cultivars studied may be explained by the fact that Oblica is the autochthonous cultivar better adapted to stress than Leccino, a cultivar from Tuscany destined for intensive cultivation and requiring either deep soils or irrigation in the summer months for regular fruit development and oil synthesis. Pinoresinol was the only compound for which changes in rainfall and temperature did not lead to the change in concentration during the observed period (

Table 3).

The studied monocultivar VOOs differed significantly regarding two different growing sites (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Among the factors under observation (growing season, growing site and time of harvest) for most of the identified phenolic compounds, the highest variability (F-statistic values) was observed by the growing site. Its strongest influence was recorded on the secoiridoid group (TOS) and their fraction. Both cultivars showed higher average content in Šestanovac, a colder and higher altitude growing site (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Although the content of phenolic compounds is related to the content of phenolic glucosides originally present in olive fruit and is determined geographically, it is usually strongly influenced by environmental factors [

20]. We found a negative correlation of the mentioned concentration of certain phenolic compounds with temperature (

Table 3), which acts as a regulatory factor for different enzymes on the pathway of phenolic synthesis, leading to the changes in final concentrations. Arslan at al. [

23] reported the highest concentration of DMOdA and DMLdA for Sariulak VOO at the higher and colder growing site. However, for total phenolic compounds, it was also observed that cultivars behaved differently depending on the growing site [

54,

55] and opposite results were also published, where a higher content was found at a lower altitude location [

56,

57]. In contrast to the behavior of the compounds belonging to the secoiridoids group, in the present study, the concentration of vanillic acid and pinoresinol was higher in both cultivars at the warmer, drier, and lower altitude growing site (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Tura et al. [

56] attributed the higher vanillic acid concentration to a higher elevation site with lower average temperatures, while Arslan et al. [

23] referred to a lower elevation site with higher average daily temperatures. This suggests that the variations in phenolic compounds caused by growing area are due to the several combined factors such as altitude, soil texture, temperature, the availability of water described earlier, but also to the different soil properties of studied olive orchards (loamy clay compared to moderately carbonate soil obtained by crushing the surface layer).

The chemical and enzymatic reactions that occur during ripening are reflected in the altered phenolic profile of the VOOs. In addition to total phenols [

31], the degree of ripening also affects the concentrations of individual phenolic compounds [

7]. Accordingly, in this study, significant differences in the content of individual phenolic compounds were found in the monocultivar Oblica and Leccino VOOs obtained from fruits with different maturity levels that ranged from 0.0 to 3.94 for Oblica fruits and from 1.05 to 4.10 for Leccino (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table S2).

Jiménez et al. [

58] reported the highest content of tyrosol and hydrotyrosol in VOOs of early harvested Picudo cultivar, and stood out that at the end of the ripening the content of hydroxytyrosol decreased by 50%. In general, our study found the same pattern of changes in simple phenols with MI incensement for both cultivars (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Exceptions, such as an increase in the middle stages of ripening (Hyt: Oblica, Šestanovac 2012; Tyr: Oblica Kaštela 2012; Leccino, Šestanovac 2011 and Kaštela 2012) and no influence of ripening (Tyr: Oblica, Kaštela 2012) were also observed. Same changes were reported by Gallina-Toschi et al. [

59] for VOOs of the Nostrana di Brisighella cultivar.

Oleuropein and ligstroside derivatives were the main phenolic fractions in all analyzed samples (

Table 1 and

Table 2), as previously described in VOO of Arbequina, Cornicabra, Picual, Chetoui, Chemalali and Buža [

60,

61,

62]. Among the different varietal VOOs studied, the group of secoiridoids does not behave the same during ripening, and the results of our research confirm that. Among the Leccino VOOs, the secoiridoids were found to peak in the mid-harvest oils (

Table 1 and

Table 2), which is consistent with the expected accumulation line of these compounds, as reported by Baccouri et al. [

61] for the monocultivar Chetoui and Chemlali VOOs. Among the identified fractions in the group of secoiridoids, a deviation from this behavior was observed only for OA-dA, VOOs from Kaštela. For Oblica VOOs, a constant decrease in secoiridoids fractions with maturation was observed (

Table 1 and

Table 2). A similar decrease in secoiridoids during maturation was observed in Arbequina, Cornicabra, and Picolimon [

60].

The dialdehyde form of the decarboxymethyloleuropein aglycone, as well as other fractions of the secoiridoids group, are derived from the secoiridoid glucosides present in olive fruit by enzymatic action during the processing of the fruit into oil [

7]. Moreover, it is known that oleuropein is the main phenolic compound of olive fruit [

63], for which Ryan et al. [

64] found a constant decrease with fruits ripening of the Cucco cultivar. However, in the same study, an increase in concentration was observed in the VOOs of Manzanillo cultivar, followed by a degradation and a decrease in oleuropein concentration. The changes in the phenolic compound content of the oils due to maturation followed the changes observed in the oleuropein concentrations. Thus, the aforementioned study suggests that the study period started late to observe the growth phase when oleuropein reaches its highest concentration (Ryan et al., 1999), which is also evident in the present study for Oblica VOOs (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

The results of flavonoid content of Oblica and Leccino VOOs are in agreement with the results of Atrajo et al. [

65], who reported that the concentrations of flavonoids in VOOs increased with olive fruit ripening. The concentration of luteolin in Oblica VOOs increased with fruit ripening, with the exception in 2012 (Kaštela), where no differences were observed during ripening (

Table 1). In the case of Leccino VOOs, a decrease in concentration was observed in VOOs obtained from overripe fruits (last harvest period) (

Table 2), which was also observed by Jiménez et al. [

58] in Picudo VOOs. Apigenin concentration increased with olive fruit ripening in both cultivars (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

3.2. Oxidative Stability as a Function of Cultivar, Environmental Conditions and Harvest Period

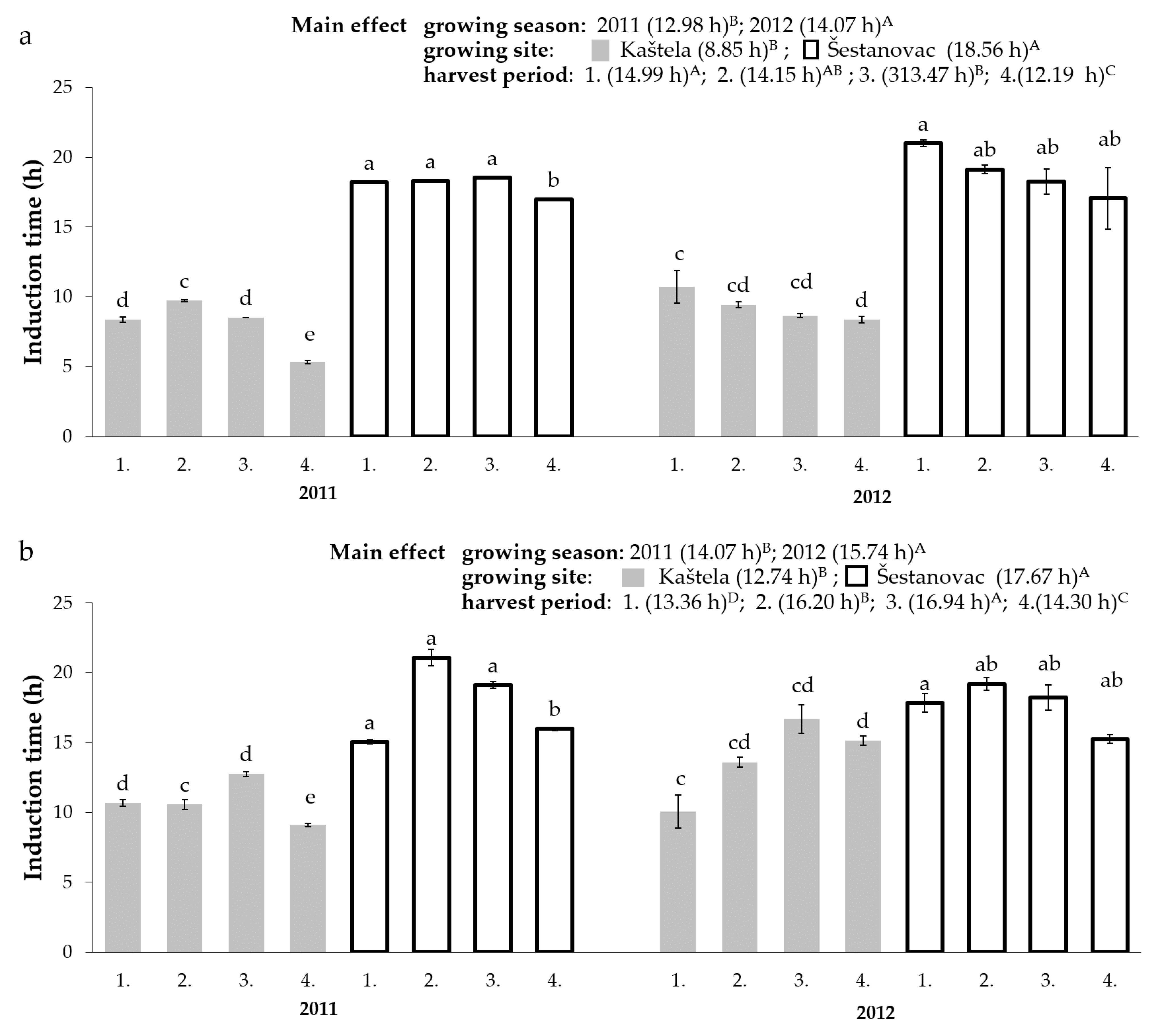

The determination of the VOO oxidative stability is its viability prediction in terms of fatty acid composition and bioactive compound content. The results shown in

Figure 1 indicate significant differences in the oxidative stability of Oblica and Leccino VOOs (F = 88.41,

p < 0.001). The oxidative stability of Oblica VOOs ranged from 5.32 to 20.99 h with the average of 13.71 h for all tested samples (

Figure 1). Leccino VOOs showed significantly higher oxidative stability values with an average value of 15.16 h (15.97–19.18 h) (

Figure 1).

The influence of climatic conditions on VOOs oxidative stability, which differed significantly between the two observed growing seasons and growing sites, was also evaluated (

Table 4). The results show that mean daily temperature during intensive olive fruits growth and ripening and rainfall in September were negatively correlated with OS. A higher average value of OS was measured in the Oblica and Leccino VOOs in 2012 (Oblica; 2011—12.99 h, 2012—14.07 h; Leccino; 2011—14.07 h, 2012—15.74 h). The reason for the lower OS values in 2011 can also be found in the loss of naturally present antioxidants (tocopherols) in specified season [

36]. Deiana et al. [

66] state that tocopherols act as synergists with phenolic compounds and thus have a significant antioxidant effect. Several studies have reported the tocopherol influence on the OS, highlighting the high tocopherol content of Leccino VOOs [

61,

67]. Moreover, a lower ratio of oleic and linoleic acids was found in the VOOs of both cultivars in 2011 [

31], which is strongly correlated with oxidative stability (r = 0.71) according to Aparicio et al. [

68].

Oxidative stability changes due to the harvest period are shown in

Figure 1. The lowest OS was found for both cultivars in VOOs from overripe olives (4th HP). The same was reported for Cornicabra VOOs [

69]. The average value of OS for Oblica VOOs (from both growing sites) (OS, Kaštela: first harvest 9.9 h, fourth harvest 7.5 h, Šestanovac: first harvest 20.0 h, fourth harvest 17.2 h) (

Figure 1) decreases with MI increasing. Most probably as the result of decreasing content of phenols (

Table 1), tocopherols, as well as changing fatty acid profile found for these VOOs [

31,

36]. For Leccino VOOs, a higher average OS value was found in the oils obtained from the second and third harvest (

Figure 1), which follows the phenols changes in these monocultivar VOOs with maturation (

Table 2).

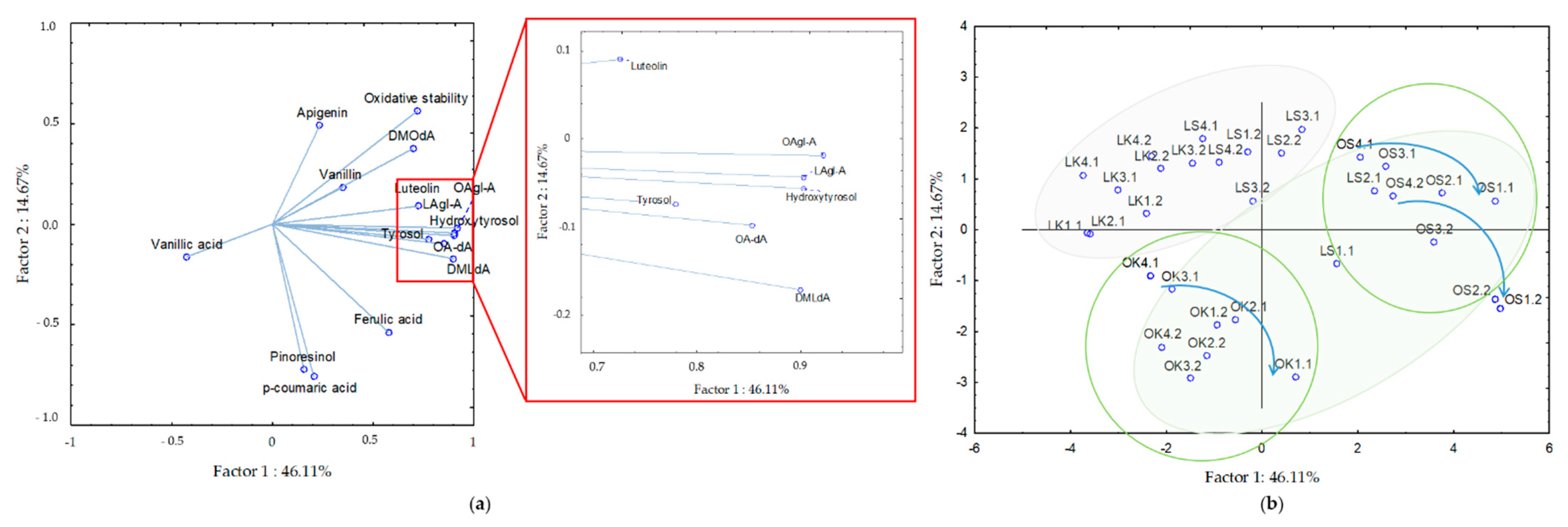

3.4. Multivariate Statistics to Identify the Hierarchy of Variance of the Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Profile and Oxidative Stability

Determining the main cause of variability in the composition of phenolic compounds and OS may be of great interest to olive oil producers in order to carry out targeted and timely harvesting and processing of the oil while maintaining the desired oil quality. In our previous report [

31], we showed that among other studied VOO characteristics, the content of total phenolics significantly depends on the cultivar. Therefore, the focus of the present study was on the specifics of phenolic composition and determination of the hierarchy of factors affecting its concentration using multivariate statistics. We subjected the entire data set (two genotypes, two growing seasons, two growing sites, and four harvest periods) to principal component analysis. The results showed that the first five principal components had eigenvalues greater than 1 and together explained 87.21% of the variance. The first principal component explained 46.11% of the total variance. A strong positive correlation with factor 1 was found for tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, and the group of secoiridoids, luteolin, and OS, whereas the correlation for vanillic acid was negative (

Figure 2a). The second principal component explained 14.67% of the total variance and was negatively correlated with pinoresinol and

p-coumaric acid (

Figure 2a). The projection also shows the strongest positive correlation of OS with the content of DMOdA (

Figure 2a), which is consistent with the research of Žanetić et al. [

71], according to which secoiridoid derivatives are responsible for antioxidant activity in native Dalmatian VOOs.

The cultivar was the first grouping variable (

Figure 2b). Samples from Leccino VOO were in the fourth quadrant (negatively correlated with factor 1 and positively correlated with factor 2). Virgin olive oils obtained from Leccino cultivar grown in Kaštela site were strongly negatively correlated with factor 1, where vanillic acid was isolated, while VOOs from the Šestanovac site were positively correlated with factor 2 and had low pinoresinol content. The first two principal components related to growing site separated samples of Oblica VOOs more strongly compared to Leccino VOOs. Oblica VOOs from Šestanovac were located in the first quadrant (positively correlated with factor 1 and factor 2) and were characterized by the higher content of simple phenols and secoiridoids (

Figure 2a,b). On the diagonally opposite side were the Oblica VOOs from Kaštela (negatively correlated with factor 1 and factor 2). A recent study using multivariate analysis showed that olive grove altitude plays an important role in differentiating olive oil samples from a single cultivar [

72].

In the present study, VOOs from the colder and wetter site of higher altitude had higher concentrations of secoiridoids and OS. In addition, the example of Oblica shows more clearly the influence of the harvest period, represented by blue curved lines (

Figure 2b). The fourth factor observed was the growing season, where a slight tendency to group the samples could be seen. However, samples from two growing seasons studied exceptionally overlapped and could not be distinguished from each other, as shown in the biplot provided (

Figure 2b). This suggests that the influence of the growing season was negligible. Nevertheless, this should be interpreted with caution, as it is possible that the weather conditions measured in the two seasons were not different enough to affect the VOOs phenolic compounds and OS and thus can be distinguished by PCA.