Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Their Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology with a Focus on Prostate Cancer—A Review—Part I: Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoid Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

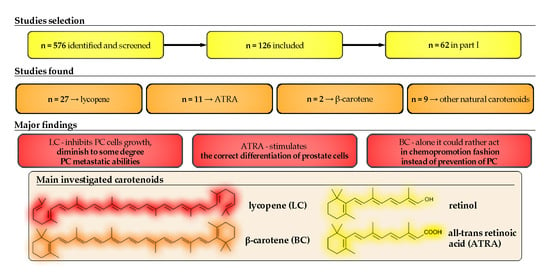

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Data Extraction

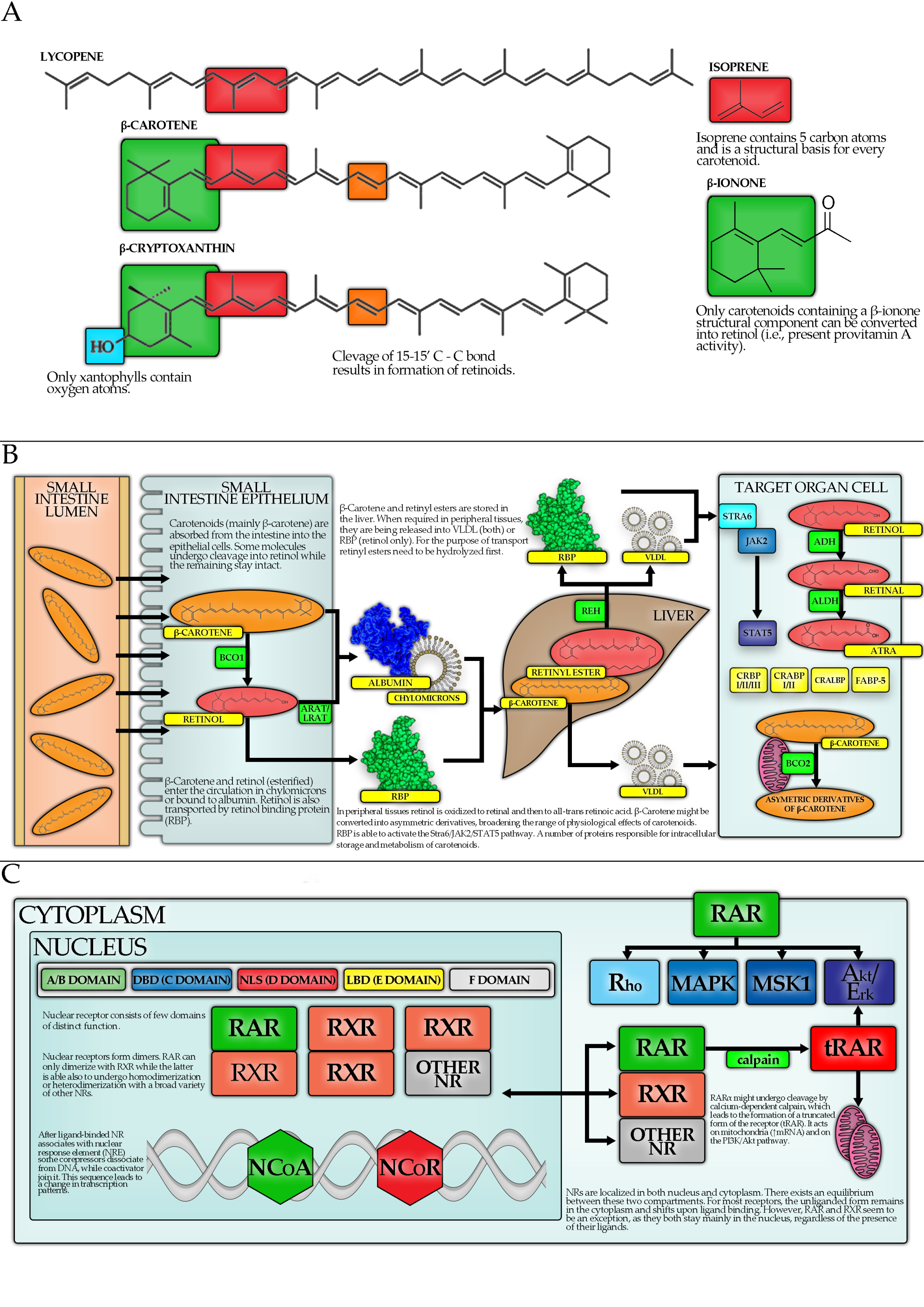

3. Carotenoids—Basic Information

- antioxidant function, e.g., quenching (deactivating) singlet oxygen [11];

- activation of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent pathway and thus upregulation of the expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes [12];

- inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), in order to prevent its migration into the nucleus, causing a decrease in the production of inflammatory cytokines [12];

- absorption of blue light by lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin in the retina of the eye.

4. Carotenoids and Hormones

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Carotenoid Metabolism

4.3. Carotenoids, Nuclear Receptors and Transcription Factors

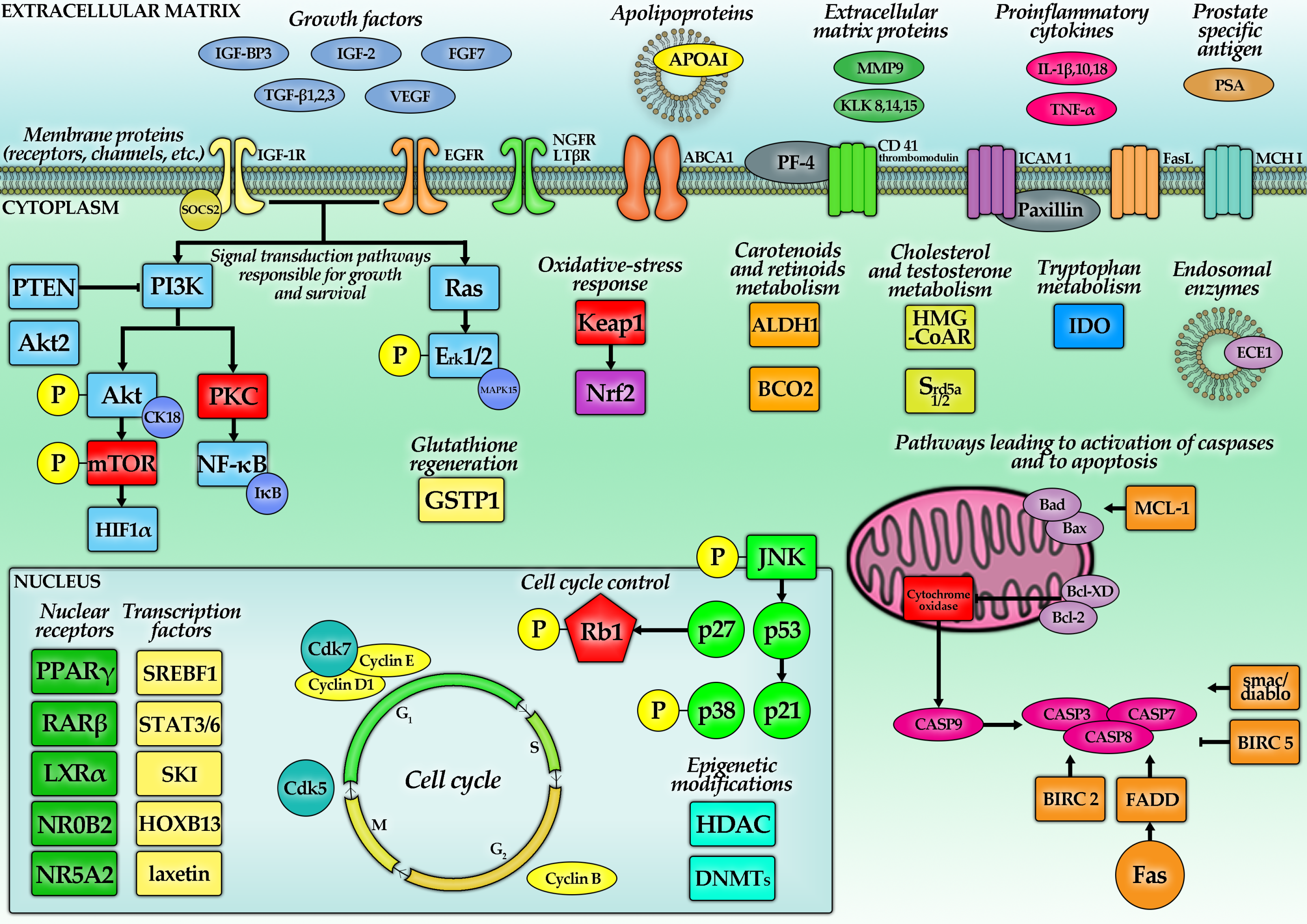

5. Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoids—Action Related to PC

| Carotenoid | Investigated Feature | Concentration Range or Dose Used/Type of Food Extract Used | Investigated Entity | Results | Commentary | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene | Growth inhibitory effect 1 | 1 µM (1–100 µM) ±1 nM docetaxel (d) or ±10–25 µM temozolomide (t) for 72 h (12–96 h) | LNCaP LAPC-4 DU145 PC-3 22Rv1 | 5%↓ (+d: 21%↓), IC50 = 2 µM 19%↓ (+d: N/C) 24%↓ (+d: 78%↓), IC50 = 3 µM N/C (+d: 21%↓, +t: 70%↓) or 25%↑ (48 h), IC50 = 4 µM 10%↓ (+d: 20%↓) | For 10 µM, the peak inhibitory effect was shown in LNCaP, Du145 and PC-3. One study found an increase of PC-3 proliferation after 1 µM or 5 µM LC. Algal LC 20–50 µM caused ~50–60%, while tomato LC caused ~40–50% growth reduction in PC-3. LC extracted from natural sourced induced a ~40–50% reduction in PC growth. | [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| Apoptosis | 10 µM for 48–96 h for 96 h | DU145 PC-3 primary PC cells | ↑ (5 x, 96 h) ↑ (2.2 x, 48 h) ↑ (1.35 x, 48 h) ↑ (2.25 x, 96 h) | Tomato paste, extract and sauce induced an average 51-fold increase in the apoptotic rate in PC cells, yielding a more pronounced result than addition of pure LC. | [68] | |

| 500–5000 µg/mL in form of tomato paste, extract, etc. | BPH cells | N/C | [70] | |||

| TNF-α + tomato extract 2 g/mL (doses 0.5–15 mg/ml) for 6 h | LNCaP DU145 | ↑ apoptosis | [73] | |||

| [LC concentration in the extract 0.9–8.6 µM] | PC-3 | Fas↑, CASP9↑, HIF1α↑ | [74] | |||

| Colony formation | 20 µM and 50 µM for 12 h | PC-3 DU145 | 110 colonies (20 µM), 59 colonies (50 µM) and 180 colonies (untreated) 76 colonies (20 µM), 35 colonies (50 µM) and 115 colonies (untreated) | LC reduced colony formation in PC-3 and DU145. | [69] | |

| Cellular accumulation | 1 μM and 3 μM for 24 h | PrEC LNCaP C4-2 DU145 PC-3 | 150 and 250 pmol/106 cells 75 and 200 pmol/106 cells 10 and 50 pmol/106 cells 20 and 80 pmol/106 cells 60 and 100 pmol/106 cells | PC cells tended to accumulate less LC than healthy prostatic tissue. | [62] | |

| Cellular adhesion and metastatic potential | 1.15 and 2.3 µM for 24 h 2 g/mL tomato extract (doses 0.5–15 mg/mL) for 6 h | PC-3 DU145 PNT2 | ↓ adhesion | Inhibition of adhesion was most pronounced for DU145 cells. | [75] | |

| [LC concentration in the extract 0.9–8.6 µM] | PC-3 | ICAM1↓, MMP9↓ | [74] | |||

| Cholesterol metabolism pathways | 2.5–10 µM for 12–48 h | LNCaP DU145 PC-3 | ↓cell cholesterol HMG-CoAR↓ ApoAI↑ PPARγ↑, LXRα↑, ABCA1↑ | Inhibition of cholesterol synthesis affected small G proteins like Ras, which require farnesylation. Cells with mutated, less stable Ras proteins were 2–3 times more prone to the LC treatment. Addition of siRNA targeted to LXRα decreased the effects of LC (caused an increase in cells’ proliferation). LC augments anti-proliferative effect of PPARγ agonists in PC | [64,65,76,77] | |

| 25 μM + 25 μM ciglitazone for 48 h | PC-3 | ↓ 82% cell proliferation | [67] | |||

| 10 µM for 24 h | PC-3 | ↓HMG-CoA | [77] | |||

| ROS, NF-κB effectors, Akt | 0.5–20 μM for 96 h | LNCaP | ↓ROS, NF-κB↓ | [68] | ||

| 2.5–10 µM for 24 h | LNCaP | ↓cyclin D1, ↓Bcl-2, ↓Bcl-XD, ↓p-Akt p53↑, p27↑, p21↑, Bax↑ | [77] | |||

| Tomato paste (30.9 mg LC/kg feed) for 10 days | male NMRI nude mice | ↓ NF-κB activity STAT3↑, STAT6↑ | PC3-κB-luc cells were injected into tomato-fed and control mice; no difference in tumor growth, reduced NF-κB in tomato-fed mice. | [74] | ||

| 10, 25 and 50 µM for 48 h | PC-3 | ↓Akt2 ↑miR-let-7f | miR-let-7f targeted Akt2 mRNA | [78] | ||

| Cell cycle, pro- and antiapoptotic proteins | 9 and 18 mg LC/kg of feed for 7 weeks | BALB/c nude mice | ↓tumor volume | The tumors in mice were induced by PC-3 cell injection. | [79] | |

| 1 µM, 2 µM and 4 µM for 24–72 h | PC cells from Gleason score 6 tumor | Bcl2↓ Bax↑ IGF-1↑ | No change was observed in the group treated with the 1 µM solution. | [80] | ||

| 0.5–5 μM for 72 h | PC-3 | ↓TNF-α | [72] | |||

| Gene methylation, GSTP1, IGF-1 | 1 μM, 2 μM, and 4 μM for 7 days | LNCaP | N/C GSTP1 N/C GSTP1 promoter methylation | LC did not have an influence on the demethylation of the GSTP1 gene promoter. | [81] | |

| 1 μM and 10 μM for 72 h | LNCaP LNCaP/IGF-IR | IC50 for LNCaP—36 µM IC50 for LNCaP/IGF-IR—0.08 µM | LNCaP/IGF-IR were 400-fold more susceptible to LC treatment. LC hypothetically interfered with the activation of IGF-IR. | [63] | ||

| BCO1 and BCO2 | 5-aza-2dC (methyltransferase inhibitor) + (in the next step) 1 μM LC for 24 h | LNCaP DU145 | BCO2↑ in LNCaP BCO2 N/C in DU145 | BCO2 levels supposedly decreased during the PC progression. Overexpression of BCO2 potentialized the antiproliferative effects of LC. | [62] | |

| Mice model studies on IGF-I pathway and use of lycopene along with cytotoxic agents | 28 mg LC/kg of feed a day in tomato powder (TP) or lycopene beadlets (LB) for 20 weeks | TRAMP mouse model | ↓ incidence of PC: 60% (LB) vs. 95% (control), p = 0.0197; N/C in IGF-I and IGF-BP3 in all groups | 30% of the LB-fed mice developed BPH, unobserved in other groups. | [82] | |

| placebo beadlets, tomato powder (providing 384 mg LC/kg diet) and LC beadlets (providing 462 mg LC/kg diet)for 4 weeks | TRAMP mouse model | 5α-reductase isoforms↓ (Srd5a1, Srd5a2) androgen receptor co-regulators↓ (Pxn and Srebf1) and changes in 30 other genes’ expression | LC interfered directly with androgen signaling. | [18] | ||

| 50 mg LC for 42 weeks +800 IU vit. E and 200 μg seleno-DL methionine for 42 weeks [control group with no supplementation] | Lady transgenic mouse (12T-10) | PC development frequency: 90% (control) 15% (suppl.) PF4↑ and CD41↑ (suppl.) | The authors suggested that PF-4 blocked angiogenesis at early stage of tumorigenesis. | [83] | ||

| Several groups: LC (15 mg/kg daily) low dose docetaxel (5 mg/kg per week) ± LC high dose docetaxel (10 mg/kg per week) ± LC for 15–74 days | NCR-nu/nu (nude) mice | ↓ tumor growth dynamics ↑38% in docetaxel’s inhibitory effect on tumor growth | DU145 cells were used to induce tumors in mice. The LC supplement in combination with the lower dose of docetaxel had the same efficacy in prolonging the life of mice as the higher dose of docetaxel. The mice were observed until the tumor reached V = 1500 mm3 or when a mouse died spontaneously. | [63] | ||

| ATRA | Growth inhibitory effect | 10–160 nM for 72 h | PC-3 DU145 | 8–62%↓ 11–65%↓ | [84] | |

| 80 nM ± 40 µM zolendronic acid (z) for 72 h 40 nM ± 20 µM zolendronic acid (z) for 72 h | PC-3 DU145 | 39%↓ (+z: 75%↓) 23%↓ (+z: 60%↓) | ||||

| 10 µM ±leucine ± β-alanine ±RARα antagonist (Ro415253) for 48 h | LNCaP | 32%↓ | Different types of ATRA conjugated with leucine or β-alanine caused similar reduction in cell number, however Ro415253 enhanced effectiveness of conjugates (but not ATRA). | [85] | ||

| 10 µM ± spermine (s) conjugated (RASP) for 24 h | LNCaP PC-3 | 10%↓ (+s: 50%↓) 10%↓ (+s: 70%↓) | [86] | |||

| 10 nM for 5 days | PC-3, LNCaP, DU145 | the minimal concentration capable of (at any degree) reducing PC cell growth in vitro | ATRA main mechanism of action was apoptosis induction, while RASP caused necrosis. | [87] | ||

| Protein level | 80 nM ± 40 µM zolendronic acid (z) for 72 h | PC-3 DU145 | CASP3, 7↑, TNRSF↑, BIRC2↓, BIRC5↓, MCL-1↓, LTβR↓, Bad↑, Bax↑, Fas↑, FADD↑, smac/diablo↑, Bcl-2↓, p53↓ | [84] | ||

| 20–120 µM for 24–72 h | DU145 | HOXB13↑ (achieved for 20–50 µM) | Methylases DNMTb3 and EZH2 were downregulated by ATRA, which resulted in activation of HOXB13 promoter. | [88] | ||

| 2 µM ± caffeic acid phenethyl ester for 24 h | PC-3, LNCaP, DU145, PrEC | thrombomodulin ↑ (except for DU145) | [89] | |||

| 1 µM ± spermine (s) conjugated (RASP) for 24 h | PC-3 | RARβ↑ | siRNA targeting RARα eliminated RARβ expression in PC-3 cells and impeded ATRA (or RASP) based effects. | [86] | ||

| 1 µM for 24 h | TAMs incubated in serum derived from PC-3 culture | IL-1β↓, IL-10↓, IDO↓, VEGF↓, MHC I↑, FasL↑, NF-κB↓ | Though ATRA reduced TAMs proliferation, their viability and functioning were not impaired significantly. | [90] | ||

| 0.1 µM or 1 µM ± 1 µM rosocovitine (r) for 24 h | DU145 | Cdk5↑, p27 N/C (+r: ↑) | [91] | |||

| 1 µM for 72 h | LNCaP | Laxetin↑ | The results strongly suggested that ATRA induced cell cycle arrest in G1 phase. | [92] | ||

| Retinol | Cellular adhesion, metastatic potential | 10 µM for 72 h | PC-3 | 13%↓ adhesion | Retinol possessed stronger anti-adhesive activity and antiproliferative than ATRA, reducing adhesion by 23% and growth by 79% in 10 µM concentration. | [93] |

| Vitamin A (ATRA + retinene + retinal + retinol) | Growth inhibitory effect Gene expression | 5–15 µM for 24–96 h 5–15 µM ± 10 µM vitamin D for 24–72 h | PC-3 | 5–25%↓ Bax↑, cyclin D1↓ | The study found that VA + VD combined reduce mitochondrial transmembrane potential. Synergistic effects were suggested. | [94] |

| β-Carotene | Growth inhibitory effect | 0–6 µM for 72 h | LNCaP, DU145 PC-3 | N/C IC50 = 13.0 ± 2.6 μM | IC50 could not have been estimated. Incubation with 6.5 μM BC decreased the activity of an AR-luciferase construct in LNCaP cells by about 40%, however it did not influence PSA secretion. CI for combination with LC was 0.65. | [71] |

| 1–5 µM for 12 h 20 µM for 12 h | PC-3 | 5%↑ 20↓ | [95] | |||

| Protein level | 1–5 µM for 12 h | PC-3 | VEGF↑ (3 ×) | For a range of 5–10 μM, the effect was weaker and regardless of the initial concentration diminished after 6 h. | [95] |

5.1. Lycopene—Studies with Cellular Models

5.1.1. Growth-Inhibitory Effects

5.1.2. Lycopene—Apoptosis, Colony Formation, Cellular Accumulation, Adhesion, and Migration

5.1.3. Lycopene—Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase (HMG-CoAR), PPARγ, LXRα and Adenosine Triphosphate-Binding Cassette Transporter Subfamily A Member 1 (ABCA1) Pathway

5.1.4. Lycopene—ROS, NF-κB and Akt

5.1.5. Lycopene—Proapoptotic and Antiapoptotic Proteins and Cell Cycle

5.1.6. Lycopene—Gene Methylation, Glutathione S-Transferase P1 (GSTP1), IGF-1

5.1.7. Lycopene—BCO1 and BCO2

5.2. Lycopene—Mice Models

5.3. Lycopene—Mechanistic Studies in Humans

5.4. Lycopene—Other Investigations

5.5. All-Trans-Retinoic Acid, Retinol and Vitamin A

5.6. β-Carotene

5.7. Other Carotenoids

6. Carotenoids and Prostatic Physiology and Pathology Other Than PC

6.1. Lycopene

6.1.1. Prostatic Hyperplasia (PH)/Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

6.1.2. Lycopene Metabolism, Impact on Prostate Physiology and Relation with Serum Testosterone

6.1.3. Anti-Inflammatory Properties and Signal Transduction

6.1.4. Cytoprotection, Redox Homeostasis, Apoptosis

6.2. Other Carotenoids

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, Y.; Cui, R.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, J.; Xu, Q. Effect of Carotene and Lycopene on the Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137427. [Google Scholar]

- Abar, L.; Vieira, A.R.; Aune, D.; Stevens, C.; Vingeliene, S.; Navarro Rosenblatt, D.A.; Chan, D.; Greenwood, D.C.; Norat, T. Blood concentrations of carotenoids and retinol. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Chen, X.; Jha, K.; Beydoun, H.; Zonderman, A.; Canas, J. Carotenoids, vitamin A, and their association with the metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 77, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, K.; Mucci, L.; Rosner, B.A.; Clinton, S.K.; Loda, M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Giovannucci, E. Dietary lycopene, angiogenesis, and prostate cancer: A prospective study in the prostate-specific antigen era. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Caballero, B.H.; Cousins, R.J.; Tucker, K.L.; Ziegler, T.R. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health Adis (ESP): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, G.A.; Hearst, J.E. Carotenoids 2: Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiokias, S.; Proestos, C.; Varzakas, T.H. A Review of the Structure, Biosynthesis, Absorption of Carotenoids-Analysis and Properties of their Common Natural Extracts. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 4, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedor, J.; Burda, K. Potential Role of Carotenoids as Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2014, 6, 466–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetkovic, D.; Nikolic, G. Carotenoids, 1st ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids; The National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Young, A.J.; Lowe, G. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Properties of Carotenoids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 385, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaulmann, A.; Bohn, T. Carotenoids, inflammation, and oxidative stress—implications of cellular signaling pathways and relation to chronic disease prevention. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas, J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, L.; Bortolotti, G.R.; Viñuela, J.; Marchant, T.A. Testosterone increases bioavailability of carotenoids: Insights into the honesty of sexual signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18633–18637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munetsuna, E.; Hojo, Y.; Hattori, M.; Ishii, H.; Kawato, S.; Ishida, A.; Kominami, S.A.J.; Yamazaki, T. Retinoic Acid Stimulates 17β-Estradiol and Testosterone Synthesis in Rat Hippocampal Slice Cultures. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4260–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.G. Cell Biology of Leydig Cells in the Testis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2004, 233, 181–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaál, A.; Csaba, G. Testosterone and progesterone level alterations in the adult rat after retinoid (retinol or retinoic acid) treatment (imprinting) in neonatal or adolescent age. Horm. Metab. Res. 1998, 30, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.K.; Stroud, C.K.; Nakamura, M.T.; Lila, M.A.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Serum Testosterone Is Reduced Following Short-Term Phytofluene, Lycopene, or Tomato Powder Consumption in F344 Rats. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Tan, H.-L.; Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Pearl, D.K.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Moran, N.E.; Clinton, S.K. Dietary Tomato and Lycopene Impact Androgen Signaling- and Carcinogenesis-Related Gene Expression during Early TRAMP Prostate Carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2014, 7, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioni, A.R.; Lania, A.; Cattaneo, A.; Beck-Peccoz, P.; Spada, A. Effects of chronic retinoid administration on pituitary function. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2005, 28, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, G.S., Jr.; Ringer, T.V.; Francom, S.F.; Means, L.K.; DeLoof, M.J. Lack of effects of beta-carotene on lipids and sex steroid hormones in hyperlipidemics. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1994, 145, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, A.; Murakami, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Fujisawa, S. Anti-inflammatory Activity of β-Carotene, Lycopene and Tri-n-butylborane, a Scavenger of Reactive Oxygen Species. In Vivo 2018, 32, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.W.; Ford, N.A.; Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Moran, N.E.; Bolton, E.C.; Wallig, M.A.; Clinton, S.K.; Erdman Jr, J.W. Mice lacking β-carotene-15,15’-dioxygenase exhibit reduced serum testosterone, prostatic androgen receptor signaling, and prostatic cellular proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 311, R1135–R1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Delves, G.H.; Chopra, M.; Lwaleed, B.A.; Cooper, A.J. Can lycopene be delivered into semen via prostasomes? In vitro incorporation and retention studies. Int. J. Androl. 2006, 29, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondin, S.A.; Yeung, E.H.; Mumford, S.L.; Zhang, C.; Browne, R.W.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Schisterman, E.F. Serum Retinol and Carotenoids in Association with Biomarkers of Insulin Resistance among Premenopausal Women. ISRN Nutr. 2013, 2013, 619516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Nakamura, M.; Ogawa, K.; Ikoma, Y.; Yano, M. High-serum carotenoids associated with lower risk for developing type 2 diabetes among Japanese subjects: Mikkabi cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015, 3, e000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, K.; Fakler, P. Protective effect of lycopene on serum cholesterol and blood pressure: Meta-analyses of intervention trials. Maturitas 2011, 68, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G.; Diamond, S.R.; Lane, J.C.; Brody, R.I.; Kayden, H.J. beta-Carotene transport in human lipoproteins. Comparisons with a-tocopherol. Lipids 1994, 29, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, E.H. Mechanisms of Transport and Delivery of Vitamin A and Carotenoids to the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1801046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy, N. Retinoid-binding proteins: Mediators of retinoid action. Biochem. J. 2000, 3, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.H.; dela Sena, C.; Eroglu, A.; Fleshman, M.K. The formation, occurrence, and function of β-apocarotenoids: β-carotene metabolites that may modulate nuclear receptor signaling. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 5, 1189S–1192S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Helden, Y.G.J.; Godschalk, R.W.L.; Swarts, H.J.M.; Hollman, P.C.H.; van Schooten, F.J.; Keijer, J. Beta-carotene affects gene expression in lungs of male and female Bcmo1 −/− mice in opposite directions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ford, N.A.; Moran, N.E.; Smith, J.W.; Clinton, S.K.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. An interaction between carotene-15,15′-monooxygenase expression and consumption of a tomato or lycopene-containing diet impacts serum and testicular testosterone. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, E133–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaduiza, E.C.; Fleet, J.C.; Russell, R.M.; Krinsky, N.I. Excentric Cleavage Products of β-Carotene Inhibit Estrogen Receptor Positive and Negative Breast Tumor Cell Growth In Vitro and Inhibit Activator Protein-1-Mediated Transcriptional Activation. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, pharmacology and treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, G.M.; Booth, L.A.; Young, A.J.; Bilton, R.F. Lycopene and beta-carotene protect against oxidative damage in HT29 cells at low concentrations but rapidly lose this capacity at higher doses. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 30, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siems, W.; Sommerburg, O.; Schild, L.; Augustin, W.; Langhans, C.-D.; Wiswedel, I. Beta-carotene cleavage products induce oxidative stress in vitro by impairing mitochondrial respiration. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siems, W.; Wiswedel, I.; Salerno, C.; Crifò, C.; Augustin, W.; Schild, L.; Langhans, C.-D.; Sommerburg, O. Beta-carotene breakdown products may impair mitochondrial functions--potential side effects of high-dose beta-carotene supplementation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005, 16, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.J.; Lowe, G.L. Carotenoids-Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Free-radicals and advanced chemistries involved in cell membrane organization influence oxygen diffusion and pathology treatment. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 240–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Kantoff, P.W.; Giovannucci, E.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Gaziano, J.M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Ma, J. Manganese superoxide dismutase polymorphism, prediagnostic antioxidant status, and risk of clinical significant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Rechavi, M.; Garcia, H.E.; Laudet, V. The nuclear receptor superfamily. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.S. Gene Regulation, Epigenetics and Hormone Signaling, 1st ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, M.I.; Xia, Z. The Retinoid X Receptors and Their Ligands. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, K.-H.; Lee, Y.-F.; Lin, W.-J.; Chu, C.-Y.; Altuwaijri, S.; Wan, Y.-J.Y.; Chang, C. 9-cis-Retinoic Acid Inhibits Androgen Receptor Activity through Activation of Retinoid X Receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, M.-T.; Richter, F.; Chang, C.; Irwin, R.J.; Huang, H. Androgen and retinoic acid interaction in LNCaP cells, effects on cell proliferation and expression of retinoic acid receptors and epidermal growth factor receptor. BMC Cancer 2002, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, F.; Huang, H.F.S.; Li, M.-T.; Danielpour, D.; Wang, S.-L.; Irwin, R.J., Jr. Retinoid and androgen regulation of cell growth, epidermal growth factor and retinoic acid receptors in normal and carcinoma rat prostate cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1999, 153, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Marcelli, M.; Weigel, N.L. Stable expression of full length human androgen receptor in PC-3 prostate cancer cells enhances sensitivity to retinoic acid but not to 1?,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Prostate 2003, 56, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vomund, S.; Schäfer, A.; Parnham, M.J.; Brüne, B.; von Knethen, A. Nrf2, the Master Regulator of Anti-Oxidative Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.-J.; Yoo, H.-S.; Shin, S.; Park, Y.-J.; Jeon, S.-M. Dysregulation of NRF2 in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilaria, B.; Scarpelli, P.; Pizzo, S.V.; Grottelli, S. ROS-independent Nrf2 activation in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 67506–67518. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, A.; Steiner, M.; Gheber, L.; Danilenko, M.; Dubi, N.; Linnewiel, K.; Zick, A.; Sharoni, Y.; Levy, J. Carotenoids activate the antioxidant response element transcription system. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacarías, L. Dietary Carotenoid Roles in Redox Homeostasis and Human Health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5733–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, S.; McClements, J.; Weiss, J.; Decker, E. Factors influencing the chemical stability of carotenoids in foods. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, V.; Lietz, G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Phelan, D.; Reboul, E.; Bánati, D.; Borel, P.; Corte-Real, J.; de Lera, A.R.; Desmarchelier, C.; et al. From carotenoid intake to carotenoid blood and tissue concentrations-implications for dietary intake recommendations. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, J.; Fleming, T.; Kliemank, E.; Brune, M.; Nawroth, P.; Fischer, A. Quantification of All-Trans Retinoic Acid by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Association with Lipid Profile in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolites 2021, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Hałubiec, P.; Łazarczyk, A.; Szafrański, O.; Sharoni, Y.; McCubrey, J.A.; Gąsiorkiewicz, B.; Bohn, T. Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology—A Review—Part II: Carotenoids in the Human Studies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gontero, P.; Marra, G.; Soria, F.; Oderda, M.; Zitella, A.; Baratta, F.; Chiorino, G.; Gregnanin, I.; Daniele, L.; Cattel, L.; et al. A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Phase I–II Study on Clinical and Molecular Effects of Dietary Supplements in Men With Precancerous Prostatic Lesions. Chemoprevention or “Chemopromotion”? Prostate 2015, 75, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, O.P.; Huttunen, J.K.; Albanes, D.; Haapakoski, J.; Palmgren, J.; Pietinen, P.; Pikkarainen, J.; Rautalahti, M.; Virtamo, J.; Edwards, B.K.; et al. The Effect of Vitamin E and Beta Carotene on the Incidence of Lung Cancer and Other Cancers in Male Smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, T.; Desmarchelier, C.; Dragsted, L.O.; Nielsen, C.S.; Stahl, W.; Rühl, R.; Keijer, J.; Borel, P. Host-related factors explaining interindividual variability of carotenoid bioavailability and tissue concentrations in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarchelier, C.; Borel, P. Overview of carotenoid bioavailability determinants: From dietary factors to host genetic variations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Marisiddaiah, R.; Zaripheh, S.; Wiener, D.; Rubin, L.P. Mitochondrial β-Carotene 9′,10′ Oxygenase Modulates Prostate Cancer Growth via NF-κB Inhibition: A Lycopene-Independent Function. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Parmakhtiar, B.; Simoneau, A.R.; Xie, J.; Fruehauf, J.; Lilly, M.; Zi, X. Lycopene enhances docetaxel’s effect in castration-resistant prostate cancer associated with insulin-like growth factor I receptor levels. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-M.; Lu, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hu, M.-L. Lycopene and the LXRα agonist T0901317 synergistically inhibit the proliferation of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells via the PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-M.; Lu, I.-H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hu, M.-L. Lycopene inhibits the proliferation of androgen-dependent human prostate tumor cells through activation of PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Patent Office. Method of Preparing Lycopene-Enriched Formulations That Are Free of Organic Solvents, Formulations Thus Obtained, Compositions Comprising Said Formulations and Use of Same. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/EP1886719A1 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Rafi, M.M.; Kanakasabai, S.; Reyes, M.D.; Bright, J.J. Lycopene modulates growth and survival associated genes in prostate cancer. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Pereira Soares, N.; Teodoro, A.J.; Oliveira, F.L.; do Nascimento Santos, C.A.; Takiya, C.M.; Saback Junior, C.M.O.; Bianco, M.; Palumbo Junior, A.; Nasciutti, L.E.; Ferreira, L.B.; et al. Influence of lycopene on cell viability, cell cycle, and apoptosis of human prostate cancer and benign hyperplastic cells. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renju, G.L.; Kurup, G.M.; Bandugula, V.R. Effect of lycopene isolated from Chlorella marina on proliferation and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell line PC-3. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 10747–10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Pereira Soares, N.; Machado, C.L.; Trindade, B.B.; do Canto Lima, I.C.; Gimba, E.R.P.; Teodoro, A.J.; Takiya, C.; Borojevic, R. Lycopene Extracts from Different Tomato-Based Food Products Induce Apoptosis in Cultured Human Primary Prostate Cancer Cells and Regulate TP53, Bax and Bcl-2 Transcript Expression. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Khanin, M.; Danilenko, M.; Zango, G.; Amosi, Y.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. The anti-cancer effects of carotenoids and other phytonutrients resides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 572, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assar, E.A.; Vidalle, M.C.; Chopra, M.; Hafizi, S. Lycopene acts through inhibition of IκB kinase to suppress NF-κB signaling in human prostate and breast cancer cells. Tumor biol. 2016, 37, 9375–9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Pereira Soares, N.; de Barros Elias, M.; Machado, C.L.; Trindade, B.B.; Borojevic, R.; Teodoro, A.J. Comparative Analysis of Lycopene Content from Different Tomato-Based Food Products on the Cellular Activity of Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Foods 2019, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, M.; Pedersen, S.; Bastani, N.E.; Carlsen, H.; Blomhoff, R.; Paur, I. Tomato paste alters NF-κB and cancer-related mRNA expression in prostate cancer cells, xenografts, and xenograft microenvironment. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgass, S.; Cooper, A.; Chopra, M. Lycopene treatment of prostate cancer cell lines inhibits adhesion and migration properties of the cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Motro, Y.; Miller, Y.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Carotenoid derivatives inhibit nuclear factor kappa B activity in bone and cancer cells by targeting key thiol groups. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 75, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palozza, P.; Colangelo, M.; Simone, R.; Catalano, A.; Boninsegna, A.; Lanza, P.; Monego, G.; Ranelletti, F.O. Lycopene induces cell growth inhibition by altering mevalonate pathway and Ras. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, L.; Zhao, W.; Hao, J.; An, R. MicroRNA-let-7f-1 is induced by lycopene and inhibits cell proliferation and triggers apoptosis in prostate cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 2708–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Han, M.; Zhang, W.; Qian, H. The suppression of torulene and torularhodin treatment on the growth of PC-3 xenograft prostate tumors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 496, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjahjodjati; Sugandi, S.; Umbas, R.; Satari, M. The Protective Effect of Lycopene on Prostate Growth Inhibitory Efficacy by Decreasing Insulin Growth Factor-1 in Indonesian Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Res. Rep. Urol. 2020, 2020, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.G.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Lycopene and apo-10′-lycopenal do not alter DNA methylation of GSTP1 in LNCaP cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 412, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijeti, R.; Henning, S.; Moro, A.; Sheikh, A.; Elashoff, D.; Shapiro, A.; Ku, M.; Said, J.W.; Heber, D.; Cohen, P.; et al. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer with lycopene in the TRAMP model. Prostate 2010, 70, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervi, D.; Pak, B.; Venier, N.; Sugar, L.; Nam, R.K.; Fleshner, N.E.; Klotz, L.; Venkateswaran, V. Micronutrients attenuate progression of prostate cancer by elevating the endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, platelet factor-4. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, B.; Karaca, B.; Atmaca, H.; Kisim, A.; Uzunoglu, S.; Sezgin, C.; Uslu, R. Regulation of apoptosis-related molecules by synergistic combination of all-trans retinoic acid and zoledronic acid in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cell lines. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010, 38, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikoglou, E.; Magoulas, G.; Theodoropoulou, C.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Giannopoulou, E.; Theodorakopoulou, O.; Drainas, D.; Papaioannou, D.; Papadimitriou, E. Effect of conjugates of all-trans-retinoic acid and shorter polyene chain analogues with amino acids on prostatecancer cell growth. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3175–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourtsis, D.; Lamprou, M.; Sadikoglou, E.; Giannou, A.; Theodorakopoulou, O.; Sarrou, E.; Magoulas, G.E.; Bariamis, S.E.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Drainas, D.; et al. Effect of an all-trans-retinoic acid conjugate with spermine on viability of human prostate cancer and endothelial cells in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 21, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.; Urban-Wójciuk, Z.; Sbirkov, Y.; Graham, A.; Hamann, A.; Brown, G. Retinoic acid receptor γ is a therapeutically targetable driver of growth and survival in prostate cancer. Cancer Rep. 2020, 3, e1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Ren, G.; Shangguan, C.; Guo, L.; Dong, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Hou, P.; Zhang, Y.; et al. ATRA Inhibits the Proliferation of DU145 Prostate Cancer Cells through Reducing the Methylation Level of HOXB13 Gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menschikowski, M.; Hagelgans, A.; Tiebel, O.; Vogel, M.; Eisenhofer, G.; Siegert, G. Regulation of thrombomodulin expression in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012, 322, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsagozis, P.; Augsten, M.; Pisa, P. All trans-retinoic acid abrogates the pro-tumorigenic phenotype of prostate cancer tumor-associated macrophages. Int. Immunophamracol. 2014, 23, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, E.; Chen, M.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hsu, S.-L.; Huang, W.J.; Lin, M.-S.; Wu, J.C.-H.; Lin, H. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Induces DU145 Cell Cycle Arrest through Cdk5 Activation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 33, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, R.I.; Taurozzi, A.J.; Wilcock, D.J.; Nappo, G.; Erb, H.H.; Read, M.L.; Gurney, M.; Archer, L.K.; Ito, S.; Rumsby, M.G.; et al. The putative tumour suppressor protein Latexin is secreted by prostate luminal cells and is downregulated in malignancy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Hsu, S.-L.; Lin, H.; Yang, T.-Y. Inhibitory Effects of Retinol Are Greater than Retinoic Acid on the Growth and Adhesion of Human Refractory Cancer Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 39, 636–640. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, J.; Pan, J.; Ping, P.; Xuan, H.; Li, D.; Bo, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y. Synergistic effect and mechanism of vitamin A and vitamin D on inducing apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 2763–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Huang, S.-M.; Yang, C.-M.; Hu, M.-L. Diverse Effects of β-Carotene on Secretion and Expression of VEGF in Human Hepatocarcinoma and Prostate Tumor Cells. Molecules 2012, 17, 3981–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi, M.M.; Kanakasabai, S.; Gokarn, S.V.; Krueger, E.G.; Bright, J.J. Dietary Lutein Modulates Growth and Survival Genes in Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Med. Food 2014, 18, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fuentes, F.; Shu, L.; Wang, C.; Pung, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Kong, A.-N. Epigenetic CpG Methylation of the Promoter and Reactivation of the Expression of GSTP1 by Astaxanthin in Human Prostate LNCaP Cells. AAPS J. 2016, 19, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festuccia, C.; Mancini, A.; Gravina, G.L.; Scarsella, L.; Llorens, S.; Alonso, G.L.; Tatone, C.; Di Cesare, E.; Jannini, E.A.; Lenzi, A. Antitumor Effects of Saffron-Derived Carotenoids in Prostate Cancer Cell Models. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaighn, M.; Narayan, K.; Ohnuki, Y.; Lechner, J.; Jones, L.W. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Investig. Urol. 1979, 17, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- van Bokhoven, A.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Korch, C.; Johannes, W.; Smith, E.; Miller, H.; Nordeen, S.; Miller, G.; Lucia, M. Molecular characterization of human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Prostate 2003, 57, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horoszewicz, J.; Leong, S.; Kawinski, E.; Karr, J.; Rosenthal, H.; Chu, T. LNCaP Model of Human Prostatic Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alimirah, F.; Chen, J.; Basrawala, Z.; Xin, H.; Choubey, D. DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cell lines express androgen receptor: Implications for the androgen receptor functions and regulation. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2294–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, S.; Sun, Y.; Squires, J.; Zhang, H.; Oh, W.; Liang, C.-Z.; Huang, J. PC3 is a cell line characteristic of prostatic small cell carcinoma. Prostate 2011, 71, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Vadlapatla, R.K.; Shah, S.; Mitra, A.K. Molecular expression and functional activity of sodium dependent multivitamin transporter in human prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 436, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.M.; Weinberg, V.; Magbanua, M.J.; Sosa, E.; Simko, J.; Shinohara, K.; Federman, S.; Mattie, M.; Hughes-Fulford, M.; Haqq, C.; et al. Nutritional supplements, COX-2 and IGF-1 expression in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magbanua, M.J.M.; Roy, R.; Sosa, E.V.; Weinberg, V.; Federman, S.; Mattie, M.D.; Hughes-Fulford, M.; Simko, J.; Shinohara, K.; Haqq, C.M.; et al. Gene expression and biological pathways in tissue of men with prostate cancer in a randomized clinical trial of lycopene and fish oil supplementation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchnov, E.A.; Amelina, E.V.; Bryzgunova, O.E.; Zaporozhchenko, I.A.; Konoshenko, M.Y.; Yarmoschuk, S.V.; Murashov, I.S.; Pashkovskaya, O.A.; Gorizkii, A.M.; Zheravin, A.A.; et al. Searching for the Novel Specific Predictors of Prostate Cancer in Urine: The Analysis of 84 miRNA Expression. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 19, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.E.; Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Fleming, J.L.; McElroy, J.P.; Mehl, R.; Grainger, E.M.; Riedl, K.M.; Toland, A.E.; Schwartz, S.J.; Clinton, S.K. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in β-Carotene Oxygenase 1 are Associated with Plasma Lycopene Responses to a Tomato-Soy Juice Intervention in Men with Prostate Cancer. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beynon, R.; Richmond, R.; Santos Ferreira, D.; Ness, A.; May, M.; Smith, G.; Vincent, E.; Adams, C.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Würtz, P. Investigating the effects of lycopene and green tea on the metabolome of men at risk of prostate cancer: The ProDiet randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 15, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvas, J.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Guy, L.; Rambeau, M.; Lyan, B.; Minet-Quinard, R.; Lobaccaro, J.-M.A.; Vasson, M.-P.; Georgé, S.; Mazur, A. Differential effects of lycopene consumed in tomato paste and lycopene in the form of a purified extract on target genes of cancer prostatic cells. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhouser, M.L.; Barnett, M.J.; Kristal, A.R.; Ambrosone, C.; King, I.B.; Thornquist, M.; Goodman, G.G. Dietary supplement use and prostate cancer risk in the Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2202–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.M.; Riboli, E.; Chatterjee, N.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Ahn, J.; Albanes, D.; Reding, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Friesen, M.D.; Hayes, R.B.; et al. Serum retinol and prostate cancer risk: A nested case-control study in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karppi, J.; Kurl, S.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Kauhanen, J. Serum β-Carotene in Relation to Risk of Prostate Cancer: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtamo, J.; Taylor, P.R.; Kontto, J.; Männistö, S.; Utriainen, M.; Weinstein, S.J.; Huttunen, J.; Albanes, D. Effects of α-tocopherol and β-carotene supplementation on cancer incidence and mortality: 18-year postintervention follow-up of the Alpha-tocopherol, Beta-carotene Cancer Prevention Study. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 1, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, T.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Ngo, V.; Roy, R.; Weinberg, V.; Song, X.; Simko, J.; Carroll, P.R.; Chan, J.M.; Paris, P.L. Associations between circulating carotenoids, genomic instability and the risk of high-grade prostate cancer. Prostate 2016, 76, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.D.; Youn, Y.K.; Shin, W.G. Positive Effects of Astaxanthin on Lipid Profiles and Oxidative Stress in Overweight Subjects. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2011, 66, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Li, S.-Y.; Qiang, J.-W.; Ji, Y.-Z. Anti-Tumor Effects of Astaxanthin by Inhibition of the Expression of STAT3 in Prostate Cancer. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Shen, S. Astaxanthin Inhibits PC-3 Xenograft Prostate Tumor Growth in Nude Mice. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formosa, A.; Markert, E.K.; Lena, A.M.; Italiano, D.; Finazzi-Agro, E.; Levine, A.J.; Bernardini, S.; Garabadgiu, A.V.; Melino, G.; Candi, E. MicroRNAs, miR-154, miR-299-5p, miR-376a, miR-376c, miR-377, miR-381, miR-487b, miR-485-3p, miR-495 and miR-654-3p, mapped to the 14q32.31 locus, regulate proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion in metastatic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2013, 33, 5173–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsumata, T.; Ishibashi, T.; Kyle, D. A sub-chronic toxicity evaluation of a natural astaxanthin-rich carotenoid extract of Paracoccus carotinifaciens in rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2014, 1, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satomi, Y. Fucoxanthin induces GADD45A expression and G1 arrest with SAPK/JNK activation in LNCap human prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rezaeeyan, Z.; Safarpour, A.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Babavalian, H.; Tebyanian, H.; Shakeri, F. High carotenoid production by a halotolerant bacterium, Kocuria sp. strain QWT-12 and anticancer activity of its carotenoid. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, Doc840. [Google Scholar]

- Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A.; Polito, F.; Irrera, N.; Marini, H.; Arena, S.; Favilla, V.; Squadrito, F.; Morgia, G.; Minutoli, L. The combination of Serenoa repens, selenium and lycopene is more effective than serenoa repens alone to prevent hormone dependent prostatic growth. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geavlete, P.; Multescu, R.; Geavlete, B. Serenoa repens extract in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2011, 3, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutoli, L.; Altavilla, D.; Marini, H.; Rinaldi, M.; Irrera, N.; Pizzino, G.; Bitto, A.; Arena, S.; Cimino, S.; Squadrito, F.; et al. Inhibitors of apoptosis proteins in experimental benign prostatic hyperplasia: Effects of serenoa repens, selenium and lycopene. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Berriguete, G.; Fraile, B.; de Bethencourt, F.R.; Prieto-Folgado, A.; Bartolome, N.; Nuñez, C.; Prati, B.; Martínez-Onsurbe, P.; Olmedilla, G.; Paniagua, R.; et al. Role of IAPs in prostate cancer progression: Immunohistochemical study in normal and pathological (benign hyperplastic, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer) human prostate. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, K. Lycopene effects contributing to prostate health. Nutr. Cancer 2009, 61, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, N.A.; Clinton, S.K.; von Lintig, J.; Wyss, A.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Loss of carotene-9’,10’-monooxygenase expression increases serum and tissue lycopene concentrations in lycopene-fed mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2134–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.B.; Besterman-Dahan, K.; Kang, L.; Pow-Sang, J.; Xu, P.; Allen, K.; Riccardi, D.; Krischer, J.P. Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial of the Action of Several Doses of Lycopene in Localized Prostate Cancer: Administration Prior to Radical Prostatectomy. Clin. Med. Insights Urol. 2008, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boileau, T.W.-M.; Clinton, S.; Zaripheh, S.; Monaco, M.H.; Donovan, S.M.; Erdman, J.W. Testosterone and food restriction modulate hepatic lycopene isomer concentrations in male F344 rats. J. Nutr. 2001, 48, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Vaishnav, A.; Tessel, M.A.; Nonn, L.; van Breemen, R.B. Effects of lycopene on protein expression in human primary prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GSTP1 Glutathione S-Transferase pi 1 [Homo Sapiens (Human)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=2950 (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Linnewiel, K.; Ernst, H.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Ben-Dor, A.; Kampf, A.; Salman, H.; Danilenko, M.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Structure activity relationship of carotenoid derivatives in activation of the electrophile/antioxidant response element transcription system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Han, M.; Zhang, W.; Qian, H. Torulene and torularhodin, protects human prostate stromal cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress damage through the regulation of Bcl-2/Bax mediated apoptosis. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.-Z.; Ni, X.-F.; Yu, H.-N.; Wang, S.-S.; Shen, S.-R. Effects of astaxanthin on oxidative stress induced by Cu2+ in prostate cells. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2017, 18, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashima, A.; Kishigami, S.; Thomson, A.; Yamada, G. Androgens and mammalian male reproductive tract development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2015, 1849, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.L.; Francis, J.C.; Lokody, I.B.; Wang, H.; Risbridger, G.P.; Loveland, K.L.; Swain, A. Sex specific retinoic acid signaling is required for the initiation of urogenital sinus bud development. Dev. Biol. 2014, 395, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Gonzalez, G.C.; Droop, A.P.; Rippon, H.J.; Tiemann, K.; Pellacani, D.; Georgopoulos, L.J.; Maitland, N.J. Retinoic acid and androgen receptors combine to achieve tissue specific control of human prostatic transglutaminase expression:a novel regulatory network with broader significance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4825–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, K.; Gudas, L.J. Retinoic acid receptors and GATA transcription factors activate the transcription of the human lecithin:retinol acyltransferase gene. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanelli, B.A.F.; Chuffa, L.G.A.; Teixeira, G.R.; Amorim, J.P.A.; Mendes, L.O.; Pinheiro, P.F.F.; Kurokawa, C.S.; Pereira, S.; Fávaro, W.J.; Martins, O.A.; et al. Chronic ethanol consumption alters all-trans-retinoic acid concentration and expression of their receptors on the prostate: A possible link between alcoholism and prostate damage. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioruci-Fontanelli, B.A.; Chuffa, L.G.A.; Mendes, L.O.; Pinheiro, P.F.F.; Justulin, L.A., Jr.; Felisbino, S.L.; Martinez, F.E. Ethanol modulates the synthesis and catabolism of retinoic acid in the rat prostate. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Carotenes | Xanthophylls |

|---|---|

| Carotene 1 | Lutein |

| Zeaxanthin | |

| Lycopene | Neoxanthin |

| Violaxanthin | |

| Phytofluene | Flavaxanthin |

| α-Cryptoxanthin | |

| Torulene | β-Cryptoxanthin |

| Type of Action | Binding Partners | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| permissive | FXR, LXR, PPAR | Ligand binding to each partner facilitates nuclear co-activator (NCoA) recruitment to promote gene expression. Binding of the second NR ligand would enhance this effect. |

| non-permissive | TR, VDR | Binding of ligand to RXR-dimerizing partner determines its ability to recruit NCoA to facilitate gene expression. Binding of the RXR ligand would not enhance this effect. |

| conditionally permissive | RAR | RAR ligand binding is a necessary condition for facilitating gene expression, but it also permits the binding of RXR agonists. RXR ligand binding would enhance transcriptional response. |

| Carotenoid or Metabolite | Increased | Decreased | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene | CASP9, Fas, HIF1α, NF-κB subunit 2, SOCS2, SKI, STAT3, STAT6 | ECE1, ICAM1, IL-18, MMP9, NF-κB, TGF-β1 | [74] |

| ABCA1, LXRα, PPARγ | HMG-CoAR | [64] | |

| ABCA1, ApoAI, LXRα, PPARγ | - | [65] | |

| ABCA1, LXRα, p21, p27, p53, PPARγ, Bax | Akt2, Bcl-2, Bcl-XD, cyclin D1, PI3K, p-Akt, p-Erk1/2, p-JNK, p-p38, NF-κB, Ras | [77] | |

| Bax, CK18 | Akt2 | [68] | |

| - | Bcl-2 | [78] | |

| Bax | - | [79] | |

| IGF-1 | - | [80] | |

| p-IκB | TNF-α | [72] | |

| BCO2 | - | [62] | |

| PF-4, CD41 | - | [83] | |

| - | Aldh1a1, Ngfr, paxillin, Srd5a1, Srd5a2, Srebf1 | [18] | |

| CASP3 | - | [73] | |

| - | Cdk7, EGFR, PSA TGF-β2 | [69] | |

| IGF-BP3 | IGF-1R | [67] | |

| β-Carotene | VEGF | - | [95] |

| All-trans-retinoic acid | HOXB13 | - | [88] |

| thrombomodulin | - | [89] | |

| RARβ | - | [86] | |

| FasL, MHC I, NF-κB | IDO, IL-1β, IL-10, VEGF | [90] | |

| Cdk5, p27 | - | [91] | |

| Laxetin | - | [92] | |

| Bax | cyclin D1 | [94] | |

| Bax, CASP3, CASP7, Fas, FADD, smac/diablo | Bcl-2, BIRC2, BIRC5, cyclin D1, LTβR, MLC-1, p53 | [84] | |

| Lutein | IGF-2, KLK8, TGF-β3 | FGF7, KLK14, KLK15, MAPK15, NR0B2, PTEN | [96] |

| Astaxanthin | DNMTs, GSTP1, HDACs, Nrf2 | - | [97] |

| Fucoxanthin | Bax, CASP3, 8, 9, p21, p27 | Bcl-2, cyclin B1, cyclin D1, cyclin E | [98] |

| Torulene | Bax, CASP3, 8, 9 | - | [79] |

| Torularhodin | Bax, CASP3, 8, 9 | Bcl-2 | [79] |

| Carotenoid | Investigated Entity | Concentration or Dose | Investigated Feature | Results | Commentary | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoxanthin | LNCaP | 4.5 μM 2.5 μM 3.8 μM | cell viability cells in G1/phase GADD45AmRNA GADD45BmRNA p-JNK p-p38 p-Erk1/2 | ↓ (−80%) ↑ (+16.2%) ↑ (3.0 x) N/C ↑ N/C ↓ | IC50 ~ 2.5 μM (3 days of treatment) | [121] |

| LNCaP DU145 PC-3 | 0.55 μM 0.84 μM 0.95 μM 1.00 μM | IC50 IC50 IC50 p21, p27, Bax, CASP3, 8, 9 cyclin B1, cyclin D1, cyclin E, Bcl-2 | 0.55 μM 0.84 μM 0.95 μM ↑ ↓ | All data for 48 h treatment. | [98] | |

| Phytoene or Phytofluene | LNCaP | 5.2 μM 4.0 μM 0.8 μM | IC50 PSA synergism with LC (0.3 μM) | 5.2 μM p > 0.05 CI = 0.13 | In each experiment, cells were additionally stimulated with 1 nM DHT. | [71] |

| PC-3 | 9.0 μM | IC50 | ||||

| Lutein | PC-3 | 10.0 μM | cell’s viability synergy 1 synergy with doxorubicin (0–100 μM) synergy with temozolomide (0–100 μM) | ↓ (−15%) N/C (+) for 10–25 μM doxorubicin (+) for 50–100 μM temozolomide | Pioglitazone and 15dPGJ2 combined with lutein showed mildly increased cell death. | [96] |

| Torulene | PC-3 mice xenografts | 18 mg/kg p.o. for 14 days after 49 days | tumor mass Bax, CASP3, 8, 9 Bcl-2 | ↓ (−72%) ↑ N/C | For each protein level, measurement torularhodin was significantly more effective than torulene. | [79] |

| Torularhodin | PC-3 mice xenografts | 18 mg/kg p.o. or 14 days after 49 days | tumor mass Bax, CASP3, 8, 9 Bcl-2 | ↓ (−76%) ↑ ↓ | ||

| Carotenoids isolated from Kocuria strain QWT-12 | PC-3 DU145 LNCaP | 0.5–0.8 mg/mL | cell’s viability | no effect | Carotenoids produced by Kocuria strain were neurosporene (dominating) and violaxanthin. | [122] |

| Lycopene’s Effect on Proteins Associated with Apoptosis Induction | |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) 40S ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) Pyruvate kinase isozyme M2 (PKM2) | ↑15–20% |

| Lycopene’s Effect on Antiapoptotic Proteins | |

| Chloride intracellular channel protein 1 (CLIC1) | ↓35% |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein (HSP70) 1A/1B HSPb1 (HSP27) Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 (Rho GDI 1) Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) Lactoylglutathione lyase 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (Grp78) Protein kinase C inhibitor protein 1 (KCIP1) | ↓10–15% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Sharoni, Y.; Hałubiec, P.; Łazarczyk, A.; Szafrański, O.; McCubrey, J.A.; Gąsiorkiewicz, B.; Laidler, P.; Bohn, T. Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Their Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology with a Focus on Prostate Cancer—A Review—Part I: Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoid Action. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10040585

Dulińska-Litewka J, Sharoni Y, Hałubiec P, Łazarczyk A, Szafrański O, McCubrey JA, Gąsiorkiewicz B, Laidler P, Bohn T. Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Their Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology with a Focus on Prostate Cancer—A Review—Part I: Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoid Action. Antioxidants. 2021; 10(4):585. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10040585

Chicago/Turabian StyleDulińska-Litewka, Joanna, Yoav Sharoni, Przemysław Hałubiec, Agnieszka Łazarczyk, Oskar Szafrański, James A. McCubrey, Bartosz Gąsiorkiewicz, Piotr Laidler, and Torsten Bohn. 2021. "Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Their Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology with a Focus on Prostate Cancer—A Review—Part I: Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoid Action" Antioxidants 10, no. 4: 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10040585

APA StyleDulińska-Litewka, J., Sharoni, Y., Hałubiec, P., Łazarczyk, A., Szafrański, O., McCubrey, J. A., Gąsiorkiewicz, B., Laidler, P., & Bohn, T. (2021). Recent Progress in Discovering the Role of Carotenoids and Their Metabolites in Prostatic Physiology and Pathology with a Focus on Prostate Cancer—A Review—Part I: Molecular Mechanisms of Carotenoid Action. Antioxidants, 10(4), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10040585