Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank

Abstract

1. Introduction

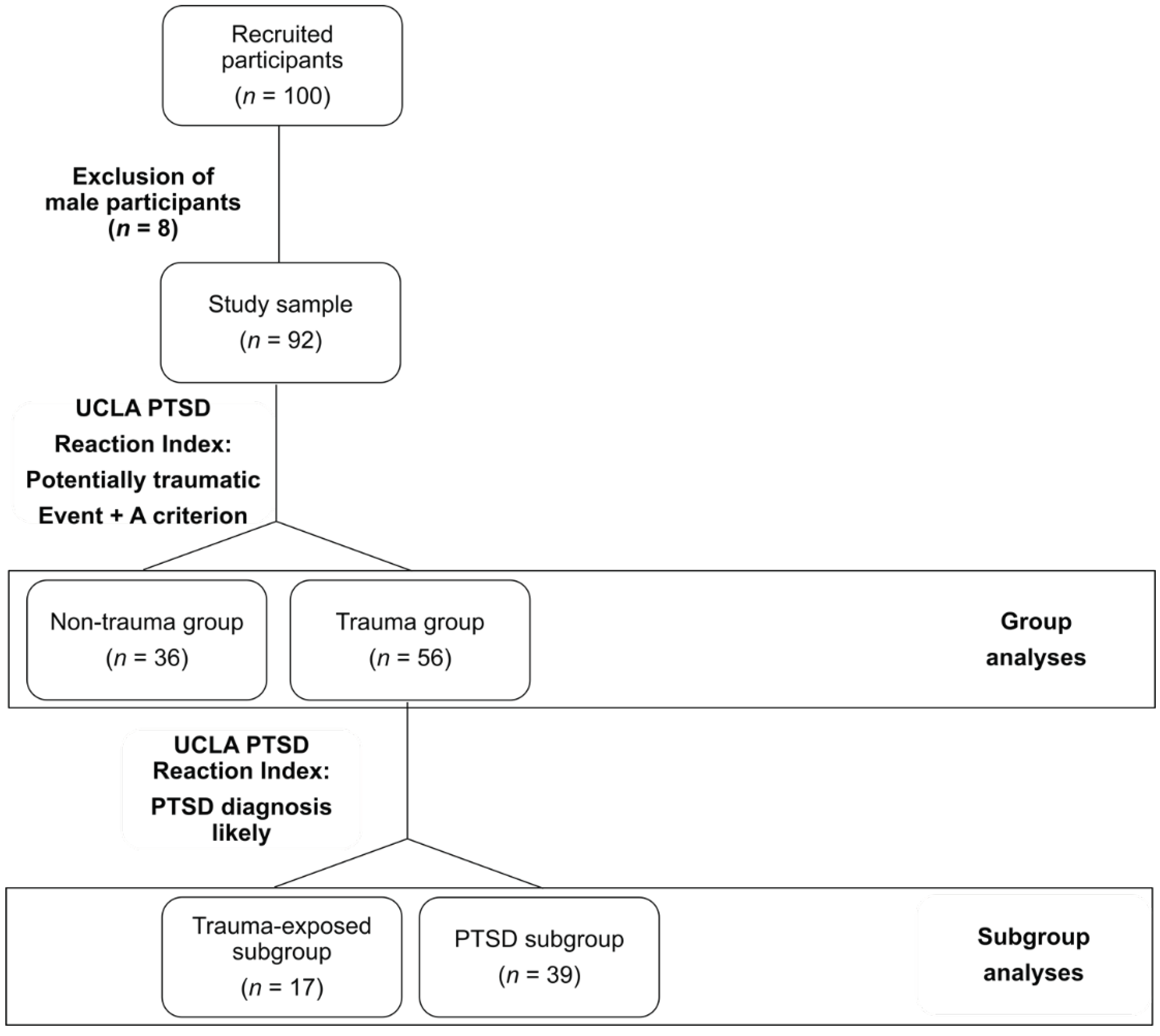

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Psychological Measures

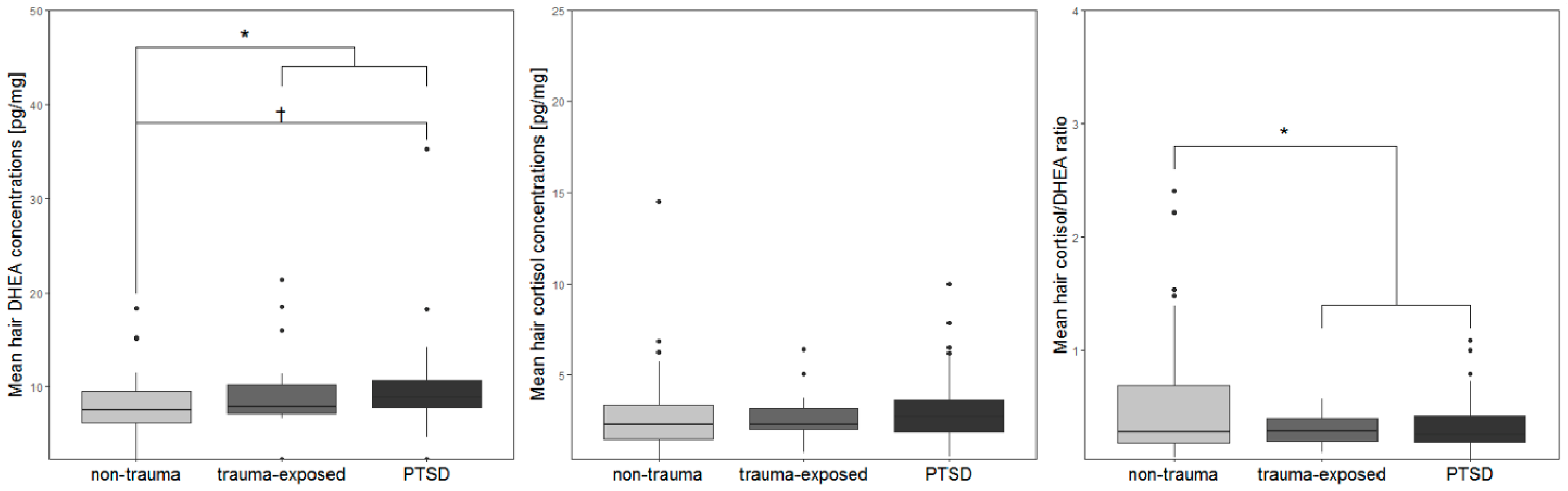

3.2. Biomarker Data from Hair Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Marx, C.E.; Pineles, S.L.; Locci, A.; Scioli-Salter, E.R.; Nillni, Y.I.; Liang, J.J.; Pinna, G. Neuroactive steroids and PTSD treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 649, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bellis, M.D.; Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Alexander, N.; Stalder, T. An integrative model linking traumatization, cortisol dysregulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: Insight from recent hair cortisol findings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 69, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.; Schindler, L.; Saar-Ashkenazy, R.; Bani Odeh, K.; Soreq, H.; Friedman, A.; Kirschbaum, C. Victims of war-Psychoendocrine evidence for the impact of traumatic stress on psychological well-being of adolescents growing up during the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Psychophysiology 2018, e13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudte, S.; Kolassa, I.-T.; Stalder, T.; Pfeiffer, A.; Kirschbaum, C.; Elbert, T. Increased cortisol concentrations in hair of severely traumatized Ugandan individuals with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajani, R.; Hadfield, K.; van Uum, S.; Greff, M.; Panter-Brick, C. Hair cortisol concentrations in war-affected adolescents: A prospective intervention trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 89, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewes, R.; Reich, H.; Skoluda, N.; Seele, F.; Nater, U.M. Elevated hair cortisol concentrations in recently fled asylum seekers in comparison to permanently settled immigrants and non-immigrants. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudte, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Gao, W.; Alexander, N.; Schonfeld, S.; Hoyer, J.; Stalder, T. Hair cortisol as a biomarker of traumatization in healthy individuals and posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, W.; Qiu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Hair cortisol level as a biomarker for altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in female adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maninger, N.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Reus, V.I.; Epel, E.S.; Mellon, S.H. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zuiden, M.; Haverkort, S.Q.; Tan, Z.; Daams, J.; Lok, A.; Olff, M. DHEA and DHEA-S levels in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analytic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 84, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hucklebridge, F.; Hussain, T.; Evans, P.; Clow, A. The diurnal patterns of the adrenal steroids cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in relation to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamin, H.S.; Kertes, D.A. Cortisol and DHEA in development and psychopathology. Horm. Behav. 2017, 89, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.R.; Pfingst, K.; Carnevali, L.; Sgoifo, A.; Nalivaiko, E. In the search for integrative biomarker of resilience to psychological stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Brand, S.R.; Golier, J.A.; Yang, R.-K. Clinical correlates of DHEA associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Vythilingam, M.; Page, G.G. Low cortisol, high DHEA, and high levels of stimulated TNF-alpha, and IL-6 in women with PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2008, 21, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, B.; Maayan, R.; Kotler, M.; Mester, R.; Gil-Ad, I.; Shtaif, B.; Weizman, A. Elevated circulatory level of GABA(A)—Antagonistic neurosteroids in patients with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Vasek, J.; Lipschitz, D.S.; Vojvoda, D.; Mustone, M.E.; Shi, Q.; Gudmundsen, G.; Morgan, C.A.; Wolfe, J.; Charney, D.S. An increased capacity for adrenal DHEA release is associated with decreased avoidance and negative mood symptoms in women with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, M.; Schnyder, U.; Schumacher, S.; Mueller-Pfeiffer, C.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Kalebasi, N.; Roos, D.; Hersberger, M.; Martin-Soelch, C. Lower plasma dehydroepiandrosterone concentration in the long term after severe accidental injury. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, E.D.; Wilkinson, C.W.; Radant, A.D.; Petrie, E.C.; Dobie, D.J.; McFall, M.E.; Peskind, E.R.; Raskind, M.A. Glucocorticoid feedback sensitivity and adrenocortical responsiveness in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 50, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli-Salter, E.; Forman, D.E.; Otis, J.D.; Tun, C.; Allsup, K.; Marx, C.E.; Hauger, R.L.; Shipherd, J.C.; Higgins, D.; Tyzik, A.; et al. Potential neurobiological benefits of exercise in chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: Pilot study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2016, 53, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Ros, C.; Herbert, J.; Martinez, M. Different profiles of mental and physical health and stress hormone response in women victims of intimate partner violence. J. Acute Dis. 2014, 3, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Voorhees, E.E.; Dennis, M.F.; Calhoun, P.S.; Beckham, J.C. Association of DHEA, DHEAS, and cortisol with childhood trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 29, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Voorhees, E.E.; Dennis, M.F.; McClernon, F.J.; Calhoun, P.S.; Buse, N.A.; Beckham, J.C. The association of dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate with anxiety sensitivity and electronic diary negative affect among smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtz, C.; Godemann, K.; von Alm, C.; Wittekind, C.; Goemann, C.; Wiedemann, K.; Yassouridis, A.; Kellner, M. Effects of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder on metabolic risk, quality of life, and stress hormones in aging former refugee children. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 199, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radant, A.D.; Dobie, D.J.; Peskind, E.R.; Murburg, M.M.; Petrie, E.C.; Kanter, E.D.; Raskind, M.A.; Wilkinson, C.W. Adrenocortical responsiveness to infusions of physiological doses of ACTH is not altered in posttraumatic stress disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, D.; Vermetten, E.; Kelley, M.E. Cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone, and estradiol measured over 24 hours in women with childhood sexual abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olff, M.; Güzelcan, Y.; de Vries, G.-J.; Assies, J.; Gersons, B.P.R. HPA- and HPT-axis alterations in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Pinna, G.; Paliwal, P.; Weisman, D.; Gottschalk, C.; Charney, D.; Krystal, J.; Guidotti, A. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, M.; Muhtz, C.; Peter, F.; Dunker, S.; Wiedemann, K.; Yassouridis, A. Increased DHEA and DHEA-S plasma levels in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and a history of childhood abuse. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olff, M.; de Vries, G.-J.; Guzelcan, Y.; Assies, J.; Gersons, B.P.R. Changes in cortisol and DHEA plasma levels after psychotherapy for PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. Personality, adrenal steroid hormones, and resilience in maltreated children: A multilevel perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, M.; Muhtz, C.; Weinås, Å.; Ćurić, S.; Yassouridis, A.; Wiedemann, K. Impact of physical or sexual childhood abuse on plasma DHEA, DHEA-S and cortisol in a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test and on cardiovascular risk parameters in adult patients with major depression or anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Pratchett, L.C.; Elmes, M.W.; Lehrner, A.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Koch, E.; Makotkine, I.; Flory, J.D.; Bierer, L.M. Glucocorticoid-related predictors and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder treatment response in combat veterans. Interface Focus 2014, 4, 20140048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, T.; Kirschbaum, C. Analysis of cortisol in hair—State of the art and future directions. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Stalder, T.; Foley, P.; Rauh, M.; Deng, H.; Kirschbaum, C. Quantitative analysis of steroid hormones in human hair using a column-switching LC-APCI-MS/MS assay. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 928, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennig, R. Potential problems with the interpretation of hair analysis results. Forensic Sci. Int. 2000, 107, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.; Quevedo, K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sagy, S.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Adolescents under rocket fire: When are coping resources significant in reducing emotional distress? Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Sagy, S. Community resilience and sense of coherence as protective factors in explaining stress reactions: Comparing cities and rural communities during missiles attacks. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, G.; Fiore, F.; Castiglioni, M.; el Kawaja, H.; Said, M. Can Sense of Coherence Moderate Traumatic Reactions?: A Cross-Sectional Study of Palestinian Helpers Operating in War Contexts. Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 43, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Eshel, Y.; Zysberg, L.; Hantman, S.; Enosh, G. Sense of coherence and socio-demographic characteristics predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms and recovery in the aftermath of the Second Lebanon War. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, P.E.; Nelson, N.; Gustafsson, P.A. Diurnal cortisol levels, psychiatric symptoms and sense of coherence in abused adolescents. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2010, 64, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almedom, A.M.; Teclemichael, T.; Romero, L.M.; Alemu, Z. Postnatal salivary cortisol and sense of coherence (SOC) in Eritrean mothers. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2005, 17, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pynoos, R.; Rodrigues, N.; Steinberg, A.; Stuber, M.; Frederick, C. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (Child Version, Revision 1); UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, A.M.; Brymer, M.J.; Decker, K.B.; Pynoos, R.S. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2004, 6, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M.M.; Orvaschel, H.; Padian, N.M.S. Children’s Symptom and Social Functioning Self-Report Scales: Comparison of Mothers’ and Children’s Reports. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980, 168, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagy, S. Effects of Personal, Family, and Community Characteristics on Emotional Reactions in a Stress Situation. Youth Soc. 1998, 29, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomer, J.; Peder, R.; Rubin, A.H.; Lavie, P. Mini Sleep Questionnaire for screening large populations for EDS complaints. In Sleep ’84; Koella, W.P., Ruther, E., Schulz, H., Eds.; Gustav Fisher: Stuttgart, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pragst, F.; Balikova, M.A. State of the art in hair analysis for detection of drug and alcohol abuse. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 370, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Data Quality Assessment. Statistical Methods for Practitioners; Scholar’s Choice: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- van Voorhees, E.; Scarpa, A. The effects of child maltreatment on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2004, 5, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schury, K.; Koenig, A.M.; Isele, D.; Hulbert, A.L.; Krause, S.; Umlauft, M.; Kolassa, S.; Ziegenhain, U.; Karabatsiakis, A.; Reister, F.; et al. Alterations of hair cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone in mother-infant-dyads with maternal childhood maltreatment. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, T.; Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Alexander, N.; Klucken, T.; Vater, A.; Wichmann, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Miller, R. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, H.; Maeshima, H.; Kida, S.; Matsuzaka, H.; Shimano, T.; Nakano, Y.; Baba, H.; Suzuki, T.; Arai, H. Serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (S) levels in medicated patients with major depressive disorder compared with controls. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 146, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA axis in major depression: Classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grass, J.; Miller, R.; Carlitz, E.H.D.; Patrovsky, F.; Gao, W.; Kirschbaum, C.; Stalder, T. In vitro influence of light radiation on hair steroid concentrations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 73, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, V.L.; van der Wulp, N.R.P.; Koper, J.W.; de Rijke, Y.B.; van Rossum, E.F.C. Hair cortisol and cortisone are decreased by natural sunlight. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 72, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Trauma Group (n = 36) | Trauma-Exposed Subgroup (n =17) | PTSD Subgroup (n = 39) | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 13.36 (1.29) | 13.41 (1.28) | 13.64 (1.33) | F2, 89 = 0.47 | 0.628 |

| Siblings (mean, SD) | 5.42 (2.17) | 4.18 (1.24) | 5.15 (1.76) | F2, 89 = 2.64 | 0.077 |

| Physical disease (%) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (5.1) | χ²2 = 1.83 | 0.401 |

| Medication (%) | 1 (4.3) a | 1 (7.7) b | 3 (13) c | χ²2 = 1.13 | 0.567 |

| Smoking (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Alcohol (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) d | 0 (0) | χ²2 = 4.74 | 0.094 |

| Drugs (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Physical development category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 4.16 | 0.842 |

| Academic level category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 5.04 | 0.753 |

| Family income category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 5.16 | 0.74 |

| Months of hair sample storage (mean, SD) | 25.54 (0.88) | 25.34 (0.79) | 25.56 (0.82) | F2, 89 = 0.46 | 0.634 |

| Non-Trauma Group (n = 36) | Trauma-Exposed Subgroup (n = 17) | PTSD Subgroup (n = 39) | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA PTSD Reaction Index | |||||

| Number of potentially traumatic events (mean, SD) | 1.25 (1.4) | 4.35 (2.78) | 4.21 (2.52) | F2, 89 = 20.3 | < 0.001I |

| Time since the worst event | - | - | - | χ²12 = 5.23 | 0.95 |

| Dissociation during the event (%) | 4 (11.1) | 7 (41.2) | 22 (56.4) | χ²2 = 16.96 | < 0.001 |

| Intrusion Severity (mean, SD) | 5.81 (5.08) | 4.88 (4.23) | 7.67 (4.07) | F2, 89 = 2.8 | 0.066 |

| Avoidance Severity (mean, SD) | 6.97 (7.44) | 2.82 (2.67) | 8.92 (3.65) | F2, 89 = 7.67 | 0.001 II |

| Arousal Severity (mean, SD) | 7.03 (5.94) | 6.12 (4.69) | 10.59 (3.47) | F2, 89 = 7.47 | 0.001 III |

| PTSD Severity (mean, SD) | 18.08 (16.85) | 12.94 (6.96) | 24.44 (8.37) | F2, 89 = 5.8 | 0.004 IV |

| STAI-Y-Trait (mean, SD) | 45.19 (6.57) | 41.47 (6.71) | 44.52 (7.21) a | F2, 89 = 1.76 | 0.178 |

| CES-DC | |||||

| Depression Severity (mean, SD) | 18.69 (11.02) | 16.24 (8.3) | 22.64 (6.62) | F2, 89 = 3.64 | 0.03 V |

| Depression Diagnosis (%) | 18 (50) | 6 (35.3) | 34 (87.2) | χ²2 = 17.99 | < 0.001 |

| MSQ (mean, SD) | 24.36 (13.68) | 27.59 (12.7) | 32.74 (11.97) | F2, 89 = 4.07 | 0.02 VI |

| SoC | |||||

| SOC-13 (mean, SD) | 55.56 (10.17) | 58.53 (11.77) | 54.77 (8.47) | F2, 89 = 0.88 | 0.417 |

| SOFC (mean, SD) | 52.66 (6.86) | 53.65 (9.13) | 50.69 (6.95) | F2, 89 = 1.19 | 0.31 |

| Biomarker | |||||

| Hair DHEA (mean, SD) | 7.77 (3.73) | 9.74 (4.77) | 9.89 (5.17) a | F2, 88 = 3.2 | 0.046 c,VII |

| Hair cortisol (mean, SD) | 2.92 (2.56) b | 2.71 (1.39) | 3.24 (2.02) | F2, 88 = 0.74 | 0.48 c |

| Hair cortisol/DHEA ratio (mean, SD) | 0.55 (0.59) | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.36 (0.25) | F2, 89 = 2.35 | 0.101 c |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schindler, L.; Shaheen, M.; Saar-Ashkenazy, R.; Bani Odeh, K.; Sass, S.-H.; Friedman, A.; Kirschbaum, C. Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

Schindler L, Shaheen M, Saar-Ashkenazy R, Bani Odeh K, Sass S-H, Friedman A, Kirschbaum C. Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sciences. 2019; 9(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchindler, Lena, Mohammed Shaheen, Rotem Saar-Ashkenazy, Kifah Bani Odeh, Sophia-Helen Sass, Alon Friedman, and Clemens Kirschbaum. 2019. "Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank" Brain Sciences 9, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

APA StyleSchindler, L., Shaheen, M., Saar-Ashkenazy, R., Bani Odeh, K., Sass, S.-H., Friedman, A., & Kirschbaum, C. (2019). Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sciences, 9(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020