In Middle-Aged Adults, Cognitive Performance Improves After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with a Cochlear Implant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Auditory Rehabilitation

2.3. Assessment of Hearing Performance

2.3.1. Freiburg Monosyllable Test

2.3.2. Oldenburg Inventory (OI)

2.4. Cognitive Testing

2.5. Patient Self-Report Questionnaires

2.5.1. Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (NCIQ)

2.5.2. General Depression Scale—Long Form (ADS-L)

2.5.3. Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ)

2.6. Statistical Tests

3. Results

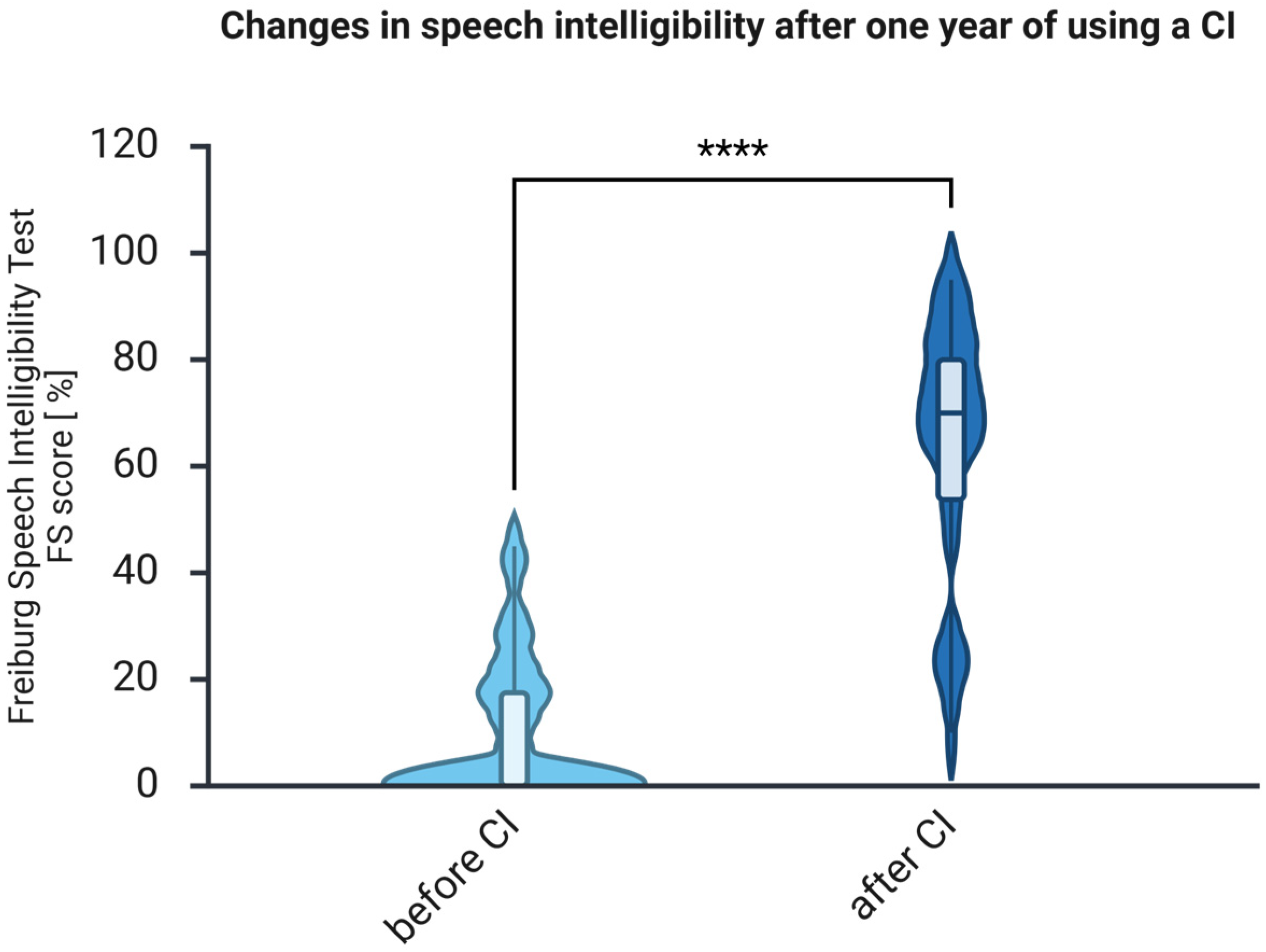

3.1. The Auditory Abilities Measured with FS Improve After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with CI

3.2. Subjective Hearing Improves After One Year of Using CI

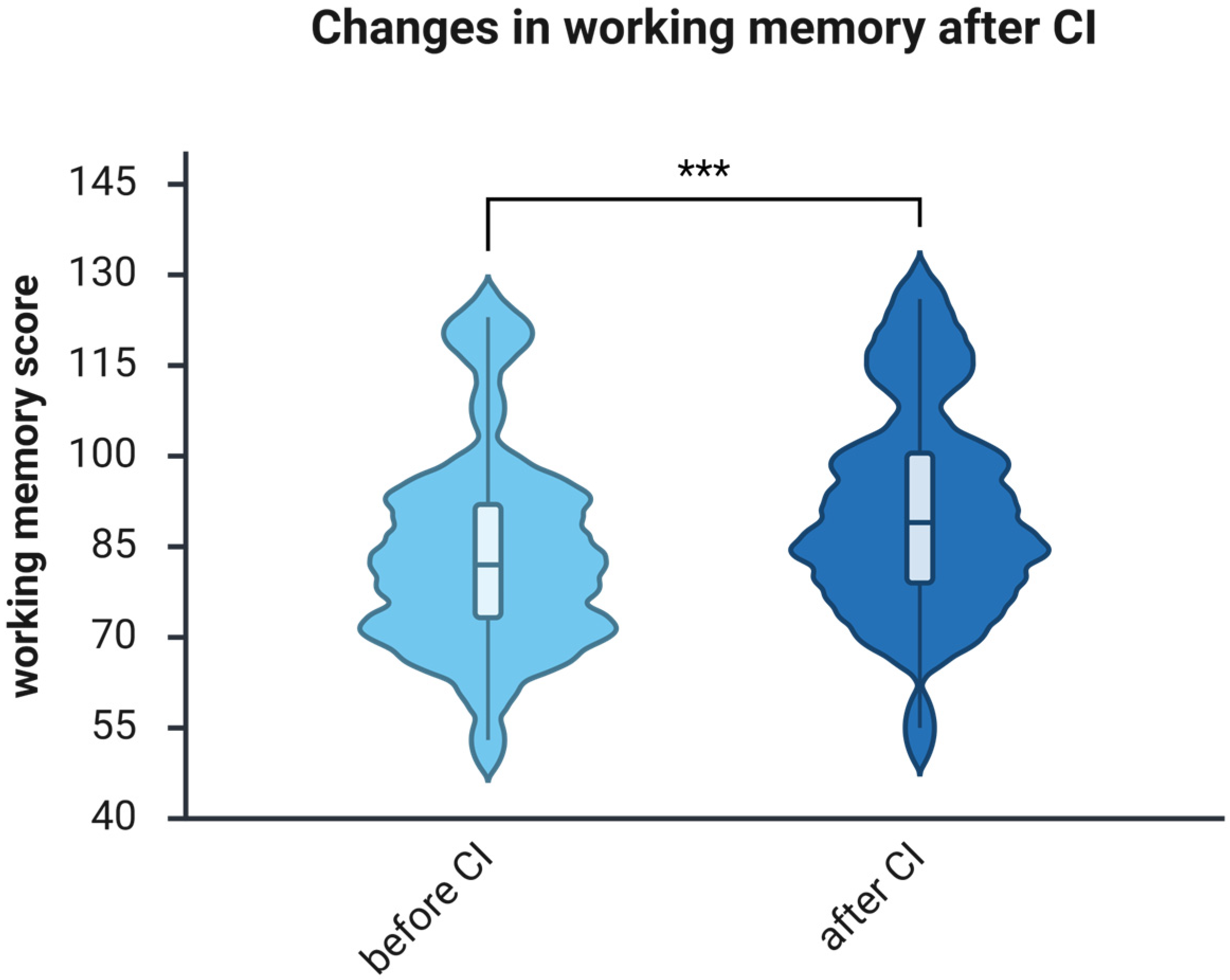

3.3. The Working Memory Improves After One Year of Using CI

3.4. The Processing Speed Improves After One Year of Using CI

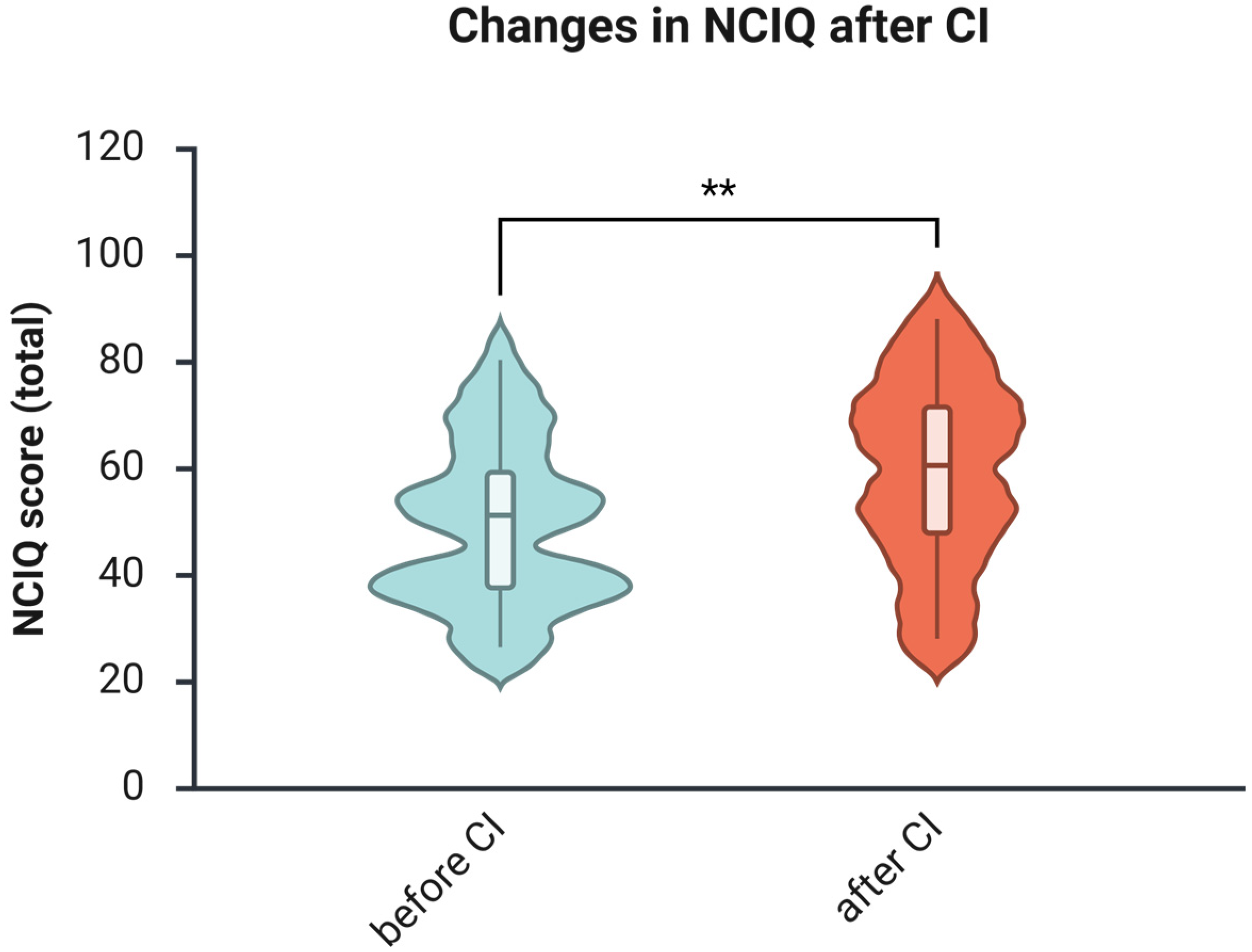

3.5. The Health-Related Quality of Life Increases After One Year of Using CI

3.6. The Depressive Symptoms Do Not Change After One Year of Using CI

3.7. The Tinnitus-Induced Distress Decreases After One Year of Using CI

3.8. Correlations Between Variables Before and After CI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADS-L | General Depression Scale (long version questionnaire) |

| AHL | Asymmetric Hearing Loss |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| FS | Freiburg Monosyllable Test (speech Intelligibility test) |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 |

| NCIQ | Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (health-related quality of life) |

| OI | Oldenburg Inventory |

| PSQ | Perceived Stress Questionnaire |

| TQ | Tinnitus Questionnaire |

References

- Mathers, C.; Smith, A.; Concha, M. Global burden of hearing loss in the year 2000. Glob. Burd. Dis. 2000, 18, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Deafness and Hearing Loss. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Nieman, C.L.; Oh, E.S. Hearing loss. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, ITC81–ITC96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, S.A.; Acar, D.; Daffner, K.R. Dementia. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, F.; Forbes, M.M. History of dementia and dementia in history: An overview. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998, 158, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peracino, A. Hearing loss and dementia in the aging population. Audiol. Neurootol. 2014, 19, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdollahi, M.; Abedi, P.; Abedi, A.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. Five insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1135–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graydon, K.; Waterworth, C.; Miller, H.; Gunasekera, H. Global burden of hearing impairment and ear disease. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2019, 133, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.S.Y.; Song, H.; Toh, E.M.S.; Ng, L.S.; Ho, C.S.H.; Ho, R.; Merchant, R.A.; Tan, B.K.J.; Loh, W.S. Association of hearing aids and cochlear implants with cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosnier, I.; Belmin, J.; Cuda, D.; Manrique Huarte, R.; Marx, M.; Ramos Macias, A.; Khnifes, R.; Hilly, O.; Bovo, R.; James, C.J.; et al. Cognitive processing speed improvement after cochlear implantation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1444330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, M.; Sánchez-Cuadrado, I.; Gavilán, J.; Gutiérrez-Revilla, M.A.; Polo, R.; Lassaletta, L. Effect of cochlear implantation on cognitive decline and quality of life in younger and older adults with severe-to-profound hearing loss. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2022, 279, 4745–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, D.E. Wechsler adult intelligence scale iv (wais iv): Return of the gold standard. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2009, 16, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dazert, S.; Thomas, J.P.; Loth, A.; Zahnert, T.; Stöver, T. Cochlear implantation: Diagnosis, indications, and auditory rehabilitation results. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde (Ed.) S2k-Leitlinie Cochlea-Implantat Versorgung; AWMF: Marburg, Germany, 2020; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, N.; Treyer, V.; Probst, R.; Kleinjung, T. Auditory cortical plasticity in patients with single-sided deafness before and after cochlear implantation. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2024, 25, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Xia, Y.; Xia, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Impact of single-side deafness on listening effort: A prospective comparative study. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2025, 10, e70185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoui, C.; Strelnikov, K.; Payoux, P.; Salabert, A.-S.; James, C.J.; Deguine, O.; Barone, P.; Marx, M. Auditory cortical plasticity after cochlear implantation in asymmetric hearing loss is related to spatial hearing: A pet h215o study. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 2229–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahlbrock, K.-H. Über sprachaudiometrie und neue wörterteste. Arch. Ohren-Nasen-Kehlkopfheilkd. 1953, 162, 394–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoth, S. Der freiburger sprachtest. HNO 2016, 64, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnhardt, E.; Laszig, R. (Eds.) Praxis der Audiometrie, 9th fully revised ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holube, I.; Kollmeier, B. Ein fragebogen zur erfassung des subjektiven hörvermögens: Erstellung der fragen und beziehung zum tonschwellenaudiogramm. Audiol. Akust. 1991, 30, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Holube, I.; Kollmeier, B. Modifikation eines fragebogens zur erlassung des subjektiven hörvermögens und dessen beziehung zur sprachverständlichkeit in ruhe und unter störgeräuschen. Audiol. Akust. 1994, 94, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Knopke, S.; Schubert, A.; Häussler, S.M.; Gräbel, S.; Szczepek, A.J.; Olze, H. Improvement of working memory and processing speed in patients over 70 with bilateral hearing impairment following unilateral cochlear implantation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, F. WAIS-IV: Deutschsprachige Adaptation nach David Wechsler. Manual 1: Grundlagen, Testauswertung und Interpretation, 2nd expanded ed.; NCS Pearson Inc.: Bloomington, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderink, J.B.; Krabbe, P.F.; Van Den Broek, P. Development and application of a health-related quality-of-life instrument for adults with cochlear implants: The Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2000, 123, 756–765, Erratum in Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2017, 156, 391.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautzinger, M.; Bailer, M.; Hofmeister, D.; Keller, F. Allgemeine Depressionsskala (ADS); 2. Überarbeitete und neu Normierte Auflage; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.; Luppa, M. Allgemeine depressionsskala (ads). Psychiatr. Prax. 2012, 39, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, G.; Hiller, W. Tinnitus-Fragebogen: (tf); ein Instrument zur Erfassung von Belastung und Schweregrad bei Tinnitus; Handanweisung; Hogrefe Verlag für Psychologie: Göttingen, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar, R.; Kaehne, A.; Kumar, N.; Kameswaran, M.; Irving, R. Systematic review of cochlear implantation in adults with asymmetrical hearing loss. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2021, 22, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoffer, J.R.; Chidarala, S.; Patel, T.; Khandalavala, K.R.; Nguyen, S.A.; Schvartz-Leyzac, K.C.; Dubno, J.R.; Carlson, M.L.; Moberly, A.C.; McRackan, T.R. Systematic review of auditory training outcomes in adult cochlear implant recipients and meta-analysis of outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, G.S.; Kocharyan, A.; Dillon, M.T.; Carlson, M.L. Cochlear implantation outcomes in adults with single-sided deafness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2023, 44, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.; Ma, C.; Nguyen, S.A.; Meyer, T.A.; Lambert, P.R. The effect of cochlear implantation on tinnitus and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2021, 42, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, L.; Junker, S.; Rattay, P.; Kuhnert, R.; Hölling, H.; Mauz, E. Trends in depressive symptoms in germany’s adult population 2008–2023. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Betz, J.; Li, L.; Blake, C.R.; Sung, Y.K.; Contrera, K.J.; Lin, F.R. Association of using hearing aids or cochlear implants with changes in depressive symptoms in older adults. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Pang, C.; Cong, N.; Han, Z. Restoration of deafferentation reduces tinnitus, anxiety, and depression: A retrospective study on cochlear implant patients. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 6678863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.; Kern, J.; Wenzel, B.; Ramirez, A.; Fawcett, M.; Pyykkonen, B. A-174 the clinical utility of rbans coding compared to wais-iv psi in community dwelling older adults. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2023, 38, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxendale, S. Iq and ability across the adult life span. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2011, 18, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisdom, N.M.; Mignogna, J.; Collins, R.L. Variability in wechsler adult intelligence scale-iv subtest performance across age. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2012, 27, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirova, A.M.; Bays, R.B.; Lagalwar, S. Working memory and executive function decline across normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 748212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.E.; Naples, J.G.; Hwa, T.; Larrow, D.C.; Campbell, F.M.; Qiu, M.; Castellanos, I.; Moberly, A.C. Emerging relations among cognitive constructs and cochlear implant outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2023, 169, 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberger, U.; Baltes, P.B. Sensory functioning and intelligence in old age: A strong connection. Psychol. Aging 1994, 9, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.R.; Ferrucci, L.; An, Y.; Goh, J.O.; Doshi, J.; Metter, E.J.; Davatzikos, C.; Kraut, M.A.; Resnick, S.M. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage 2014, 90, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peelle, J.E.; Wingfield, A. The neural consequences of age-related hearing loss. Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Lindenberger, U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbitt, P.M. Channel-capacity, intelligibility and immediate memory. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1968, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichora-Fuller, M.K. Cognitive aging and auditory information processing. Int. J. Audiol. 2003, 42, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, N.Y.S.; Nouchi, R.; Oba, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Kawashima, R. Auditory cognitive training improves brain plasticity in healthy older adults: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 826672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Kang, H.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, D.S. Brain plasticity can predict the cochlear implant outcome in adult-onset deafness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.R.; Zobay, O.; Ferguson, M.A. Minimal and mild hearing loss in children: Association with auditory perception, cognition, and communication problems. Ear Hear. 2020, 41, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Population/Age, Range | Cognitive Measure Used | Key Findings | Methodological Weaknesses | Research Gaps | How the Present Study Addresses the Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosnier et al. (2024) [14] | 100 CI users; 60–64, 65–75, ≥75 | MMSE, TMT-B, Digit Symbol Coding, TUG | Cognitive improvement only in the 60–64 group; auditory gains | No adults < 60 included | No evaluation of WMI or PSI with full WAIS-IV Only one WAIS-IV subtest was used (Digit Coding) Midlife cognitive effects were not assessed | Focuses on midlife adults; uses full WAIS-IV WMI and PSI. Provides midlife-specific cognitive data with standardized measures. |

| Calvino et al. (2022) [15] | 28 CI users ≤ 60 and ≥61 | RBANS-H (attention, memory, visuospatial) | Cognitive improvement in both age groups | Broad age categories without specific midlife delineation | No targeted analysis of midlife adults RBANS-H does not isolate WM or PS | Specifically includes midlife adults Applies WAIS-IV, the gold standard for WMI and PSI |

| Parameter | Number of Patients or a Mean with SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52.4 (9.6) |

| Sex | 14 women and 18 men |

| Freiburg Monosyllabic Test result on the ear scheduled for implantation | 9.2 (13.1) |

| Type of hearing loss | |

| AHL (asymmetric hearing loss) | 7 |

| SSD (single-sided or unilateral deafness) | 11 |

| DSD (double-sided or bilateral deafness) | 14 |

| Cause of hearing loss | |

| acoustic trauma | 1 |

| an accident | 1 |

| autoimmune disease | 1 |

| cholesteatoma | 1 |

| Ménière’s disease | 1 |

| middle ear infection | 2 |

| noise-induced hearing loss | 1 |

| sudden hearing loss | 8 |

| surgery | 1 |

| unknown | 9 |

| Highest education level | |

| no education | 1 |

| primary school | 5 |

| comprehensive school | 17 |

| grammar school | 2 |

| technical college | 3 |

| university | 2 |

| no data | 2 |

| Working Memory Before CI | Processing Speed Before CI | NCIQ Total | ADSL | OI Total | TQ Total | Level of Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | processing speed before CI | Correlation Coefficient | 0.533 ** | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | ||||||||

| n | 32 | ||||||||

| NCIQ total | Correlation Coefficient | 0.208 | 0.048 | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.289 | 0.809 | |||||||

| n | 28 | 28 | |||||||

| ADSL | Correlation Coefficient | −0.029 | −0.335 | −0.163 | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.888 | 0.087 | 0.416 | ||||||

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | ||||||

| OI total | Correlation Coefficient | −0.004 | 0.037 | 0.781 ** | −0.066 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.984 | 0.854 | <0.001 | 0.743 | |||||

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | |||||

| TQ total | Correlation Coefficient | −0.059 | 0.059 | −0.383 * | 0.234 | −0.137 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.772 | 0.770 | 0.049 | 0.251 | 0.505 | ||||

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | ||||

| level of education | Correlation Coefficient | 0.452 * | 0.320 | 0.230 | −0.004 | 0.315 | −0.016 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.012 | 0.084 | 0.239 | 0.985 | 0.109 | 0.938 | |||

| n | 30 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 27 | |||

| age | Correlation Coefficient | −0.031 | 0.035 | −0.088 | −0.059 | −0.036 | 0.184 | −0.238 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.864 | 0.851 | 0.658 | 0.770 | 0.858 | 0.359 | 0.206 | ||

| n | 32 | 32 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 30 | ||

| Working Memory After CI | Processing Speed After CI | NCIQ Total | ADSL | OI Total | TQ Total | Level of Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | processing speed after CI | Correlation Coefficient | 0.516 ** | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | ||||||||

| n | 32 | ||||||||

| NCIQ total | Correlation Coefficient | 0.361 | 0.510 ** | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.059 | 0.006 | |||||||

| n | 28 | 28 | |||||||

| ADSL | Correlation Coefficient | −0.171 | −0.261 | −0.476 * | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.394 | 0.189 | 0.012 | ||||||

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | ||||||

| OI total | Correlation Coefficient | 0.279 | 0.400 * | 0.858 ** | −0.312 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.159 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 0.114 | |||||

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | |||||

| TQ total | Correlation Coefficient | −0.459 * | −0.381 | −0.720 ** | 0.591 ** | −0.624 ** | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.021 | 0.060 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | ||||

| level of education | Correlation Coefficient | 0.496 ** | 0.378 * | 0.296 | 0.005 | 0.280 | −0.161 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.005 | 0.040 | 0.143 | 0.981 | 0.165 | 0.464 | |||

| n | 30 | 30 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 23 | |||

| age | Correlation Coefficient | −0.019 | −0.035 | −0.149 | 0.016 | −0.049 | −0.104 | −0.238 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.916 | 0.848 | 0.448 | 0.935 | 0.806 | 0.620 | 0.206 | ||

| n | 32 | 32 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 30 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zuberbier, J.; Szczepek, A.J.; Olze, H. In Middle-Aged Adults, Cognitive Performance Improves After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with a Cochlear Implant. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010022

Zuberbier J, Szczepek AJ, Olze H. In Middle-Aged Adults, Cognitive Performance Improves After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with a Cochlear Implant. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuberbier, Jaron, Agnieszka J. Szczepek, and Heidi Olze. 2026. "In Middle-Aged Adults, Cognitive Performance Improves After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with a Cochlear Implant" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010022

APA StyleZuberbier, J., Szczepek, A. J., & Olze, H. (2026). In Middle-Aged Adults, Cognitive Performance Improves After One Year of Auditory Rehabilitation with a Cochlear Implant. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010022