Attentional Selection and Allocation to Alarm Signals in Complex Environments: The New Electrophysiological Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Experimental Procedure

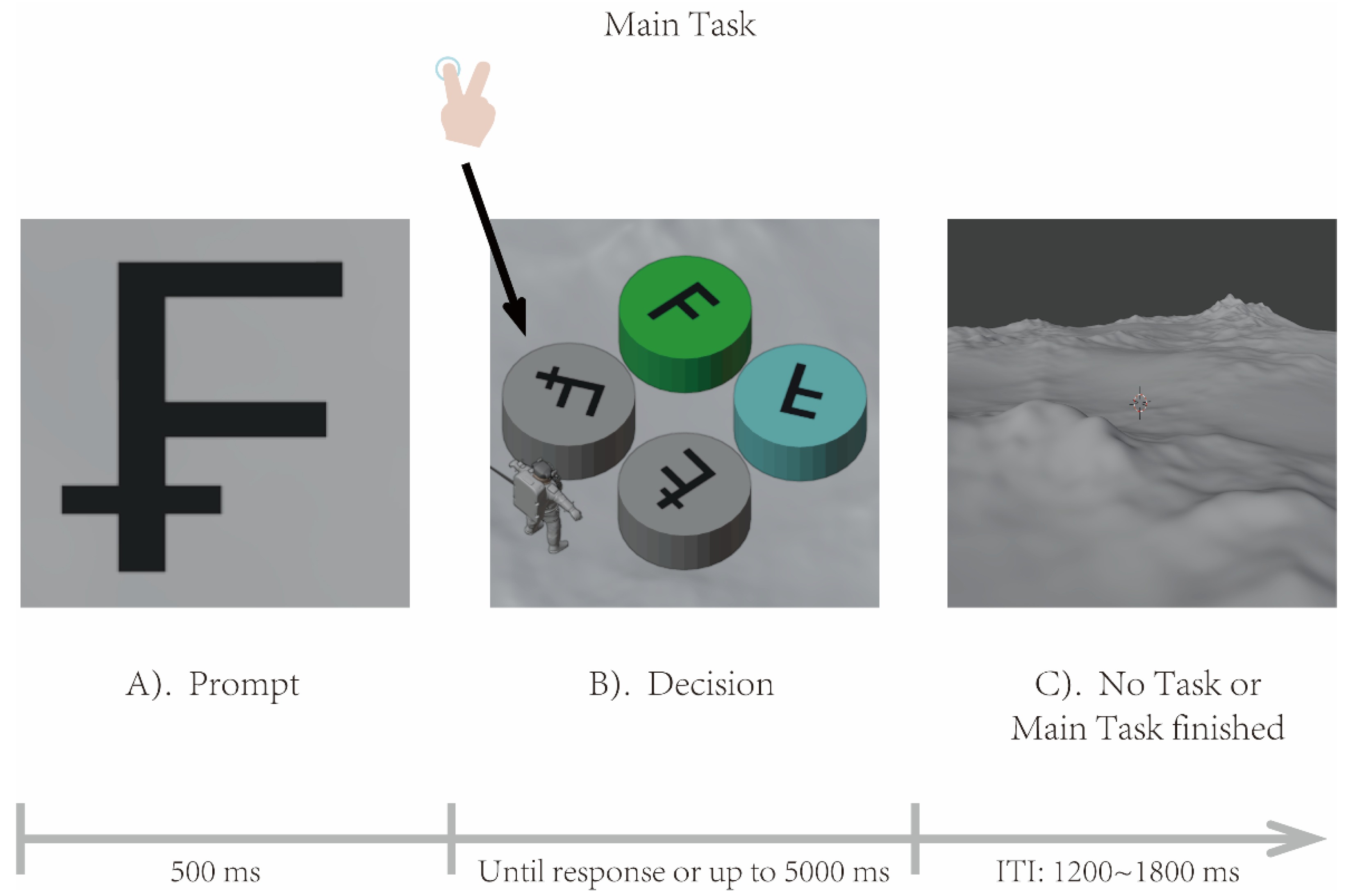

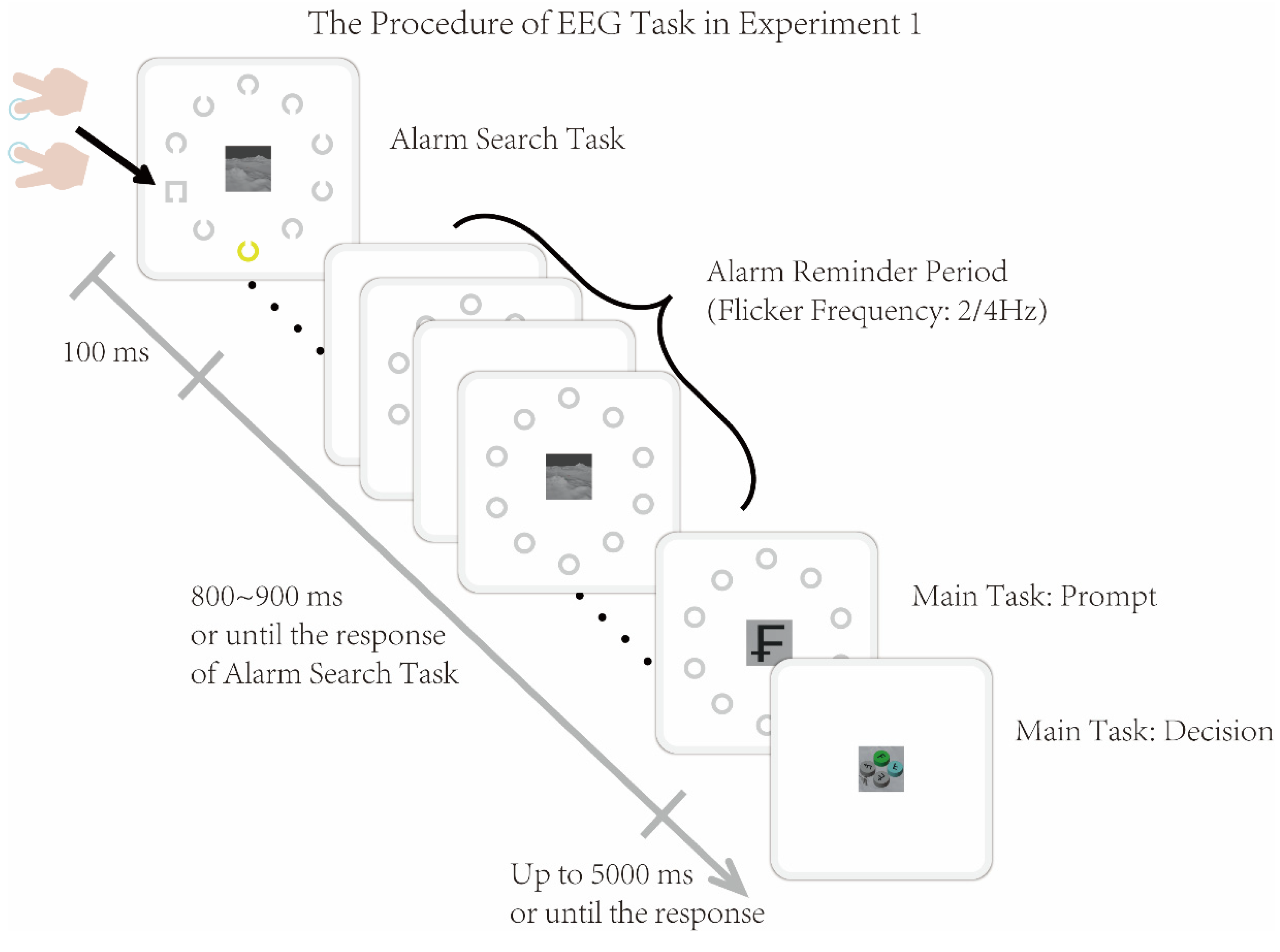

EEG Task

Cognition Tests

2.1.3. Electroencephalography Recording and Preprocessing

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Results

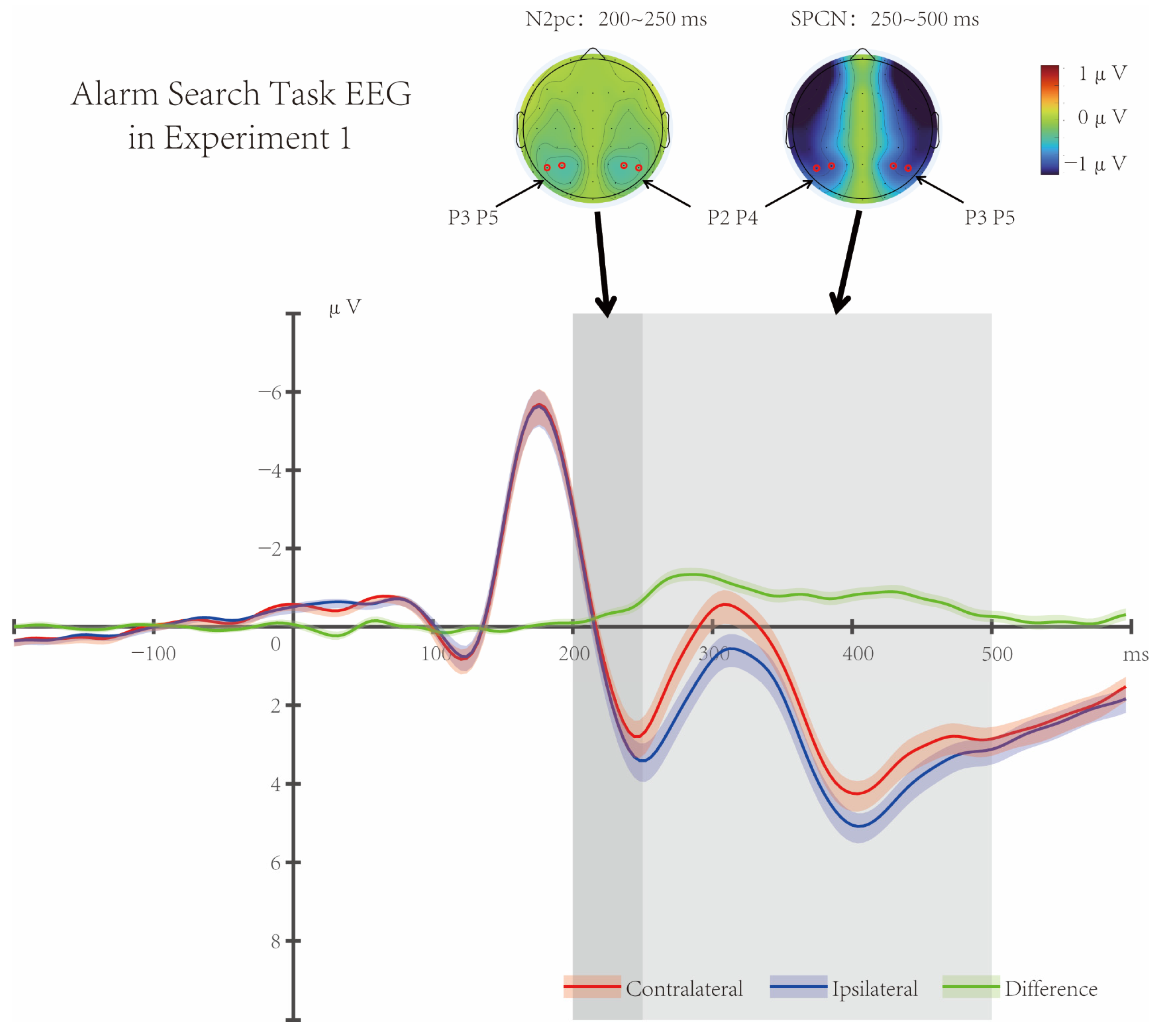

2.2.1. EEG Results

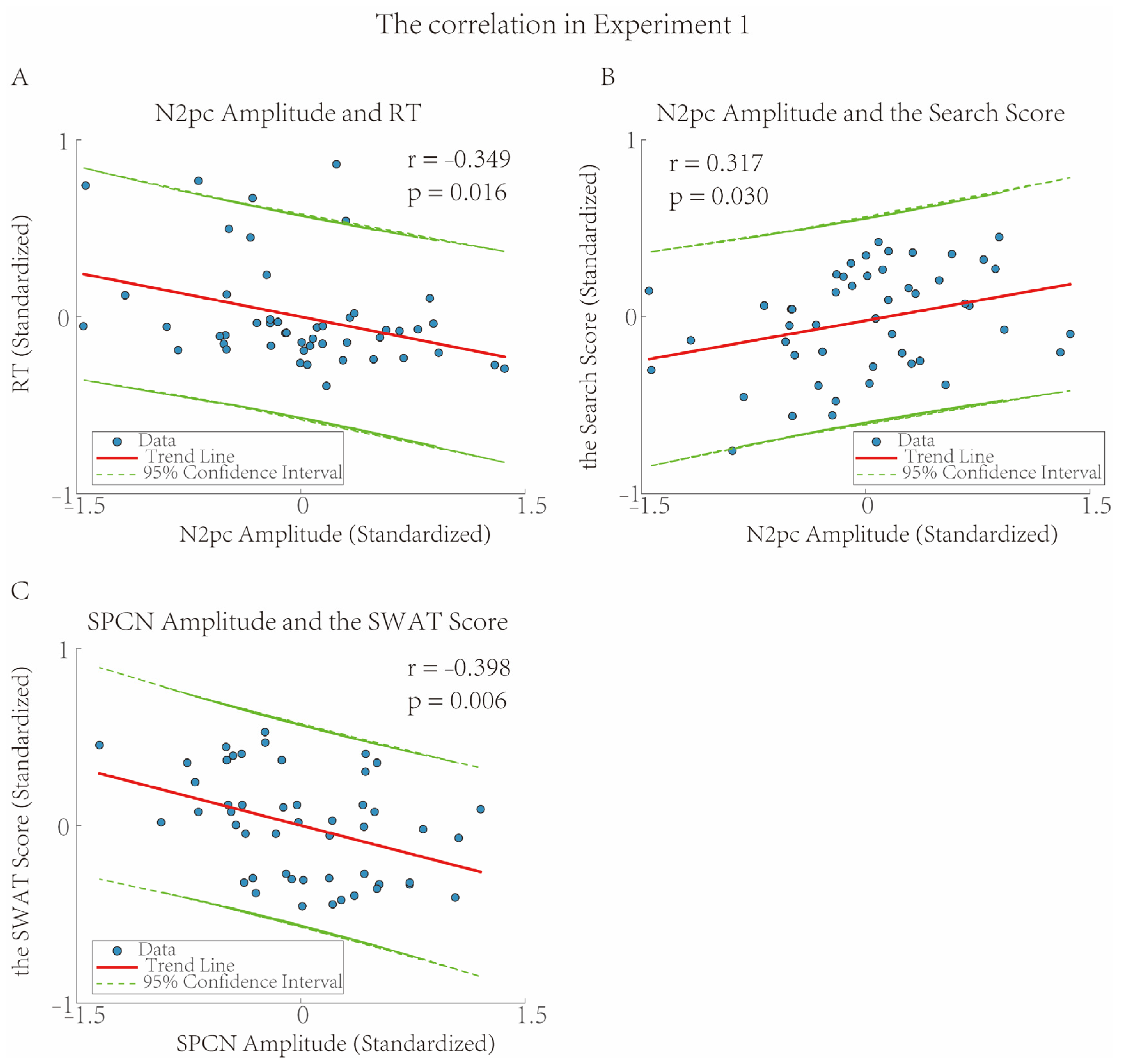

2.2.2. Correlation of EEG and Behavioral Performance

2.2.3. Correlation of EEG and Cognition Tests

2.3. Discussion

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

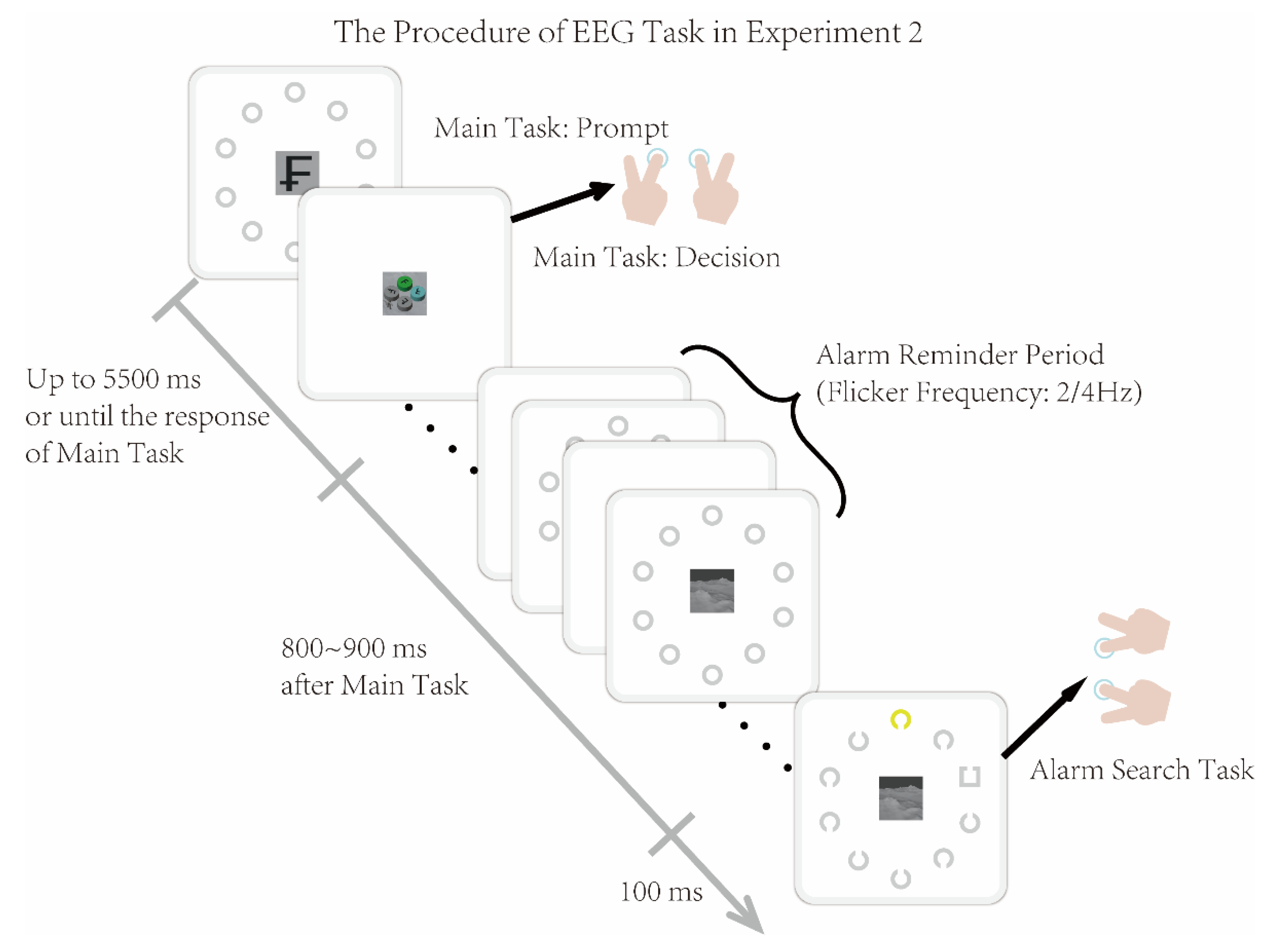

3.1.2. Experimental Procedure

3.1.3. Electroencephalography Recording and Preprocessing

3.1.4. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

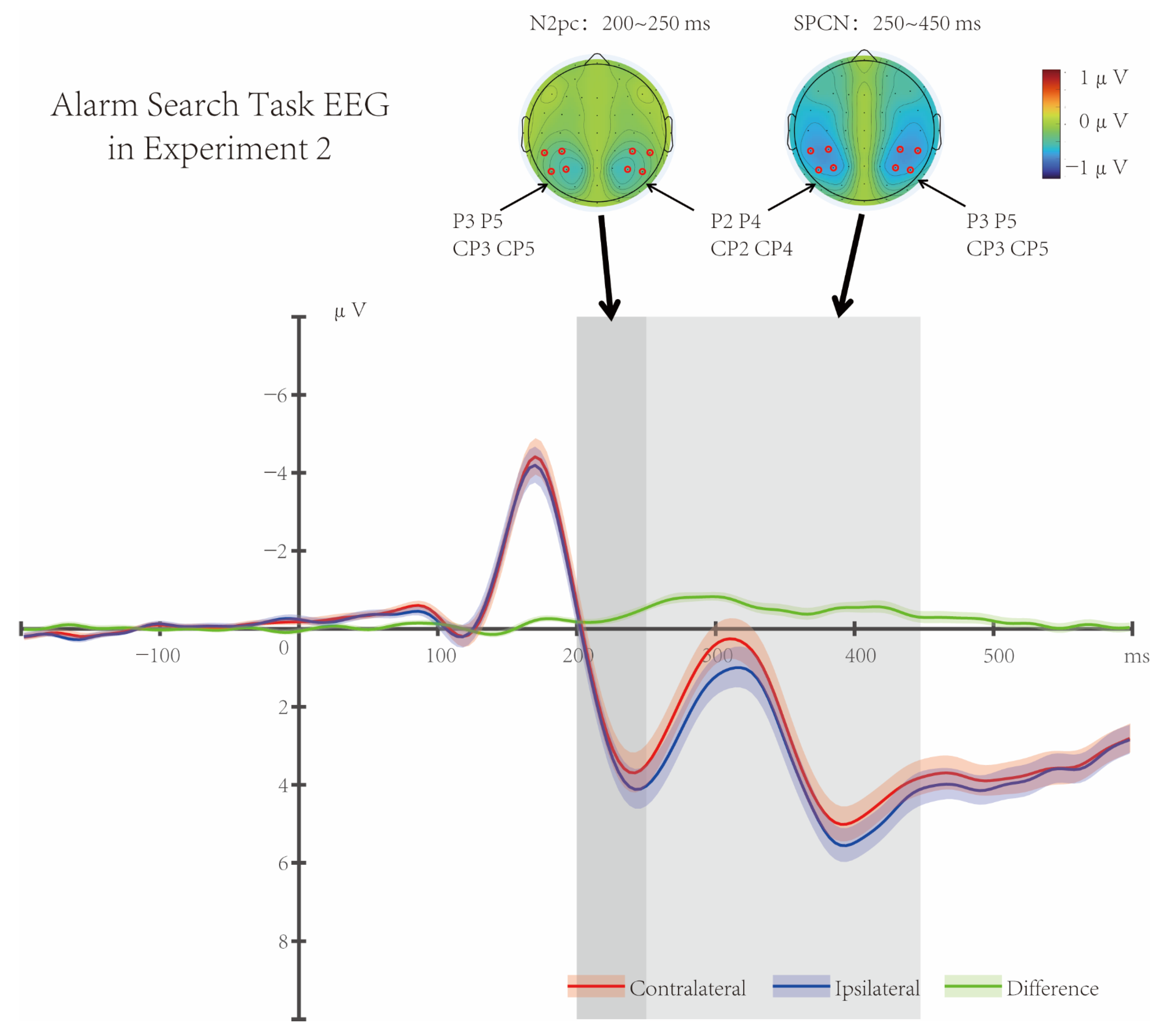

3.2.1. EEG Results

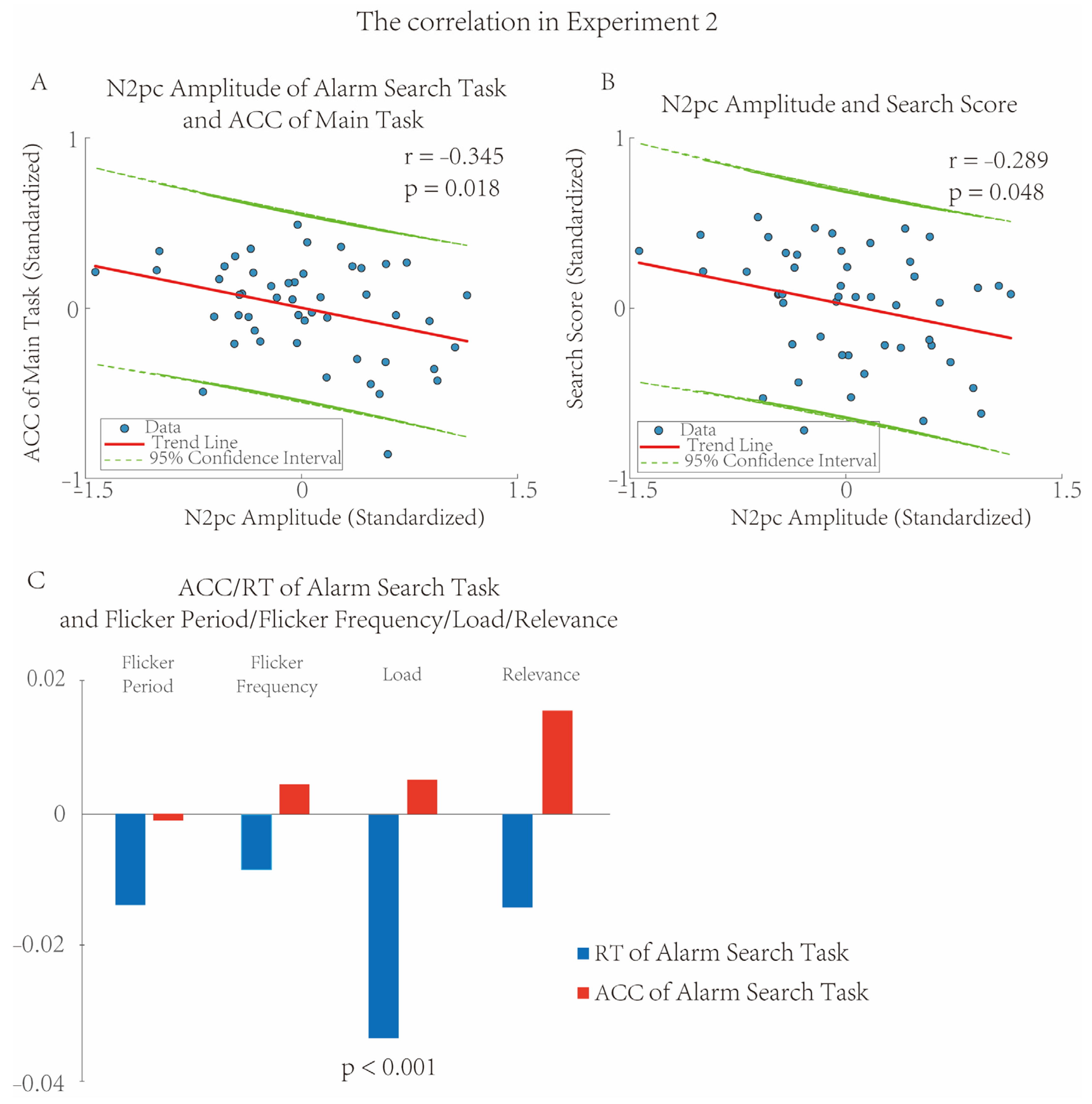

3.2.2. Subject-Wised Correlation of EEG and Behavioral Performance

3.2.3. Trial-Wise Correlation of Main Task/Alarm Reminder Period and Alarm Search Task

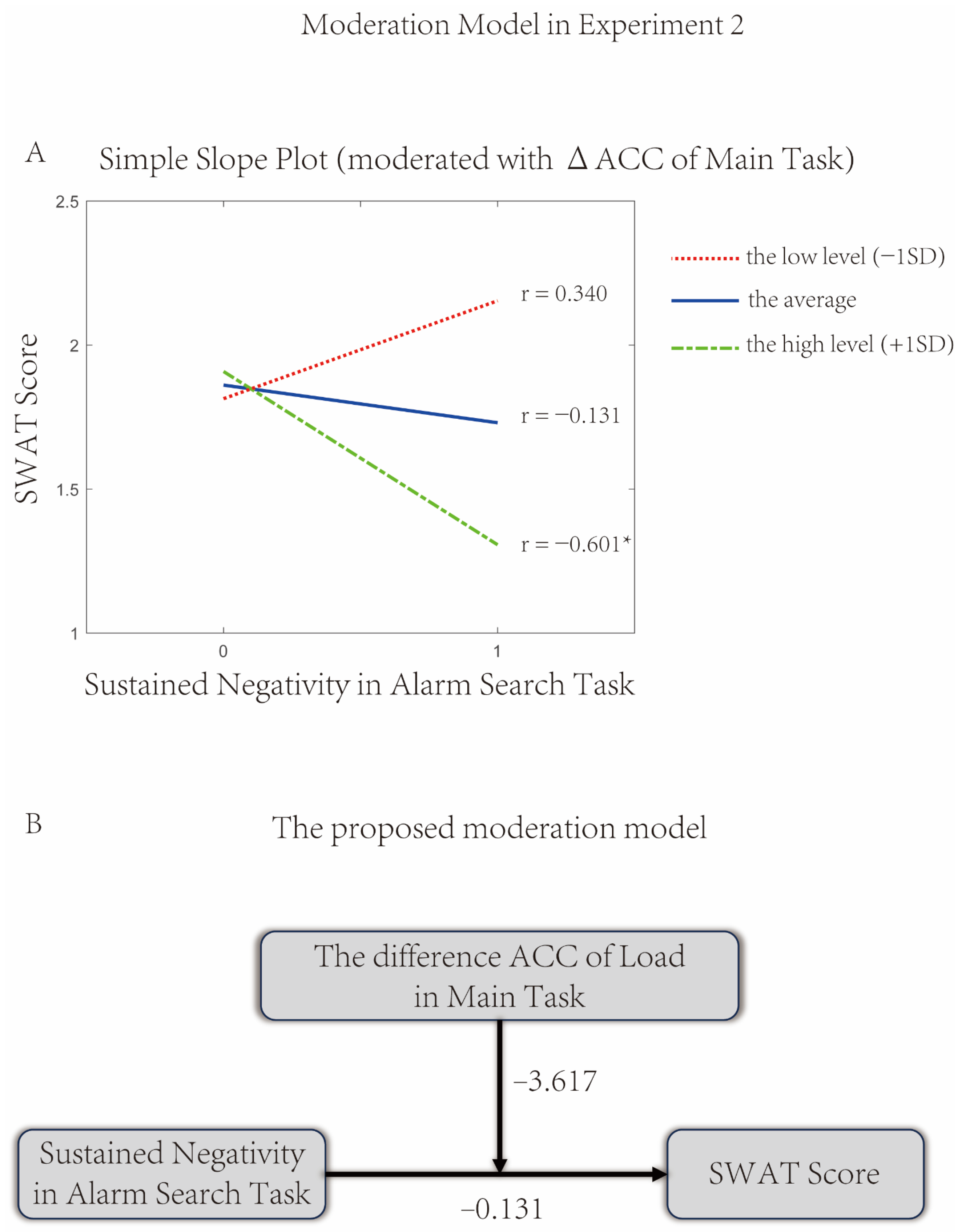

3.2.4. The Moderating Effect of Main Task Load

- Model 1 included the independent variable (sustained negativity) and two control variables (i.e., age and gender)

- Model 2 added the moderator variable (∆ACC) based on Model 1

- Model 3 further added the interaction term (sustained negativity × ∆ACC) based on Model 2.

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Alarm Signals Detection Requires the Continuous Attentional Allocation in Complex Environments

4.2. Alarm Signal Detection Differs from Ordinary Target Search at the Selective Attention Stage

4.3. The Dual-Task Paradigm Serves as a Tool to Investigate the Attentional Resource Allocation Across Tasks

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Causse, M.; Parmentier, F.B.; Mouratille, D.; Thibaut, D.; Kisselenko, M.; Fabre, E. Busy and confused? High risk of missed alerts in the cockpit: An electrophysiological study. Brain Res. 2022, 1793, 148035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudet, L.; St-Louis, M.-E.; Scannella, S.; Causse, M. P300 event-related potential as an indicator of inattentional deafness? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickens, C.; Colcombe, A. Dual-task performance consequences of imperfect alerting associated with a cockpit display of traffic information. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2007, 49, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, P.; Li, W.-C.; Yu, C.-S.; Braithwaite, G. The impact of alerting designs on air traffic controller’s eye movement patterns and situation awareness. Ergonomics 2019, 62, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, K.; Griffiths, T.D.; Chait, M.; Lavie, N. Inattentional deafness: Visual load leads to time-specific suppression of auditory evoked responses. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 16046–16054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili Bijarsari, S. A current view on dual-task paradigms and their limitations to capture cognitive load. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashler, H. Dual-task interference in simple tasks: Data and theory. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z. The impact of different types of auditory warnings on working memory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 780657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Ma, X.; You, X. The effect of working memory load on inattentional deafness during aeronautical decision-making. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 113, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac-Auliffe, D.; Chatard, B.; Petton, M.; Croizé, A.-C.; Sipp, F.; Bontemps, B.; Gannerie, A.; Bertrand, O.; Rheims, S.; Kahane, P.; et al. The dual-task cost is due to neural interferences disrupting the optimal spatio-temporal dynamics of the competing tasks. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 640178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.R.; Pereira, A.R.; Vieira, J.; Pereira, F.; Marques, R.; Campos, G.; Sampaio, A.; Crego, A. Capturing the attentional response to clinical auditory alarms: An ERP study on priority pulses. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M. Research on effective recognition of alarm signals in a human–machine system based on cognitive neural experiments. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 29, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanada, M.; Shimada, M.; Katayama, J. Auditory P3a reflects attentional process, not response inhibition to deviant processing: An ERP study with three-stimulus oddball paradigm. Exp. Brain Res. 2025, 243, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehais, F.; Roy, R.N.; Scannella, S. Inattentional deafness to auditory alarms: Inter-individual differences, electrophysiological signature and single trial classification. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 360, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolicœur, P.; Brisson, B.; Robitaille, N. Dissociation of the N2pc and sustained posterior contralateral negativity in a choice response task. Brain Res. 2008, 1215, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolke, B.; Festl, F.; Seibold, V.C. Toward the influence of temporal attention on the selection of targets in a visual search task: An ERP study. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 1690–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimer, M. The N2pc component as an indicator of attentional selectivity. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 99, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, S.J.; Hillyard, S.A. Spatial filtering during visual search: Evidence from human electrophysiology. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1994, 20, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, B.; Jolicœur, P. Electrophysiological evidence of central interference in the control of visuospatial attention. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2007, 14, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M.; Van Velzen, J.; Eimer, M. The N2pc component and its links to attention shifts and spatially selective visual processing. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, N.; Eimer, M. Object-based target templates guide attention during visual search. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2018, 44, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Causse, M.; Imbert, J.-P.; Giraudet, L.; Jouffrais, C.; Tremblay, S. The role of cognitive and perceptual loads in inattentional deafness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Qi, H.; He, F.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Ming, D. An EEG-based mental workload estimator trained on working memory task can work well under simulated multi-attribute task. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.K.; Vartanian, O.; Hollands, J.G. The brain under cognitive workload: Neural networks underlying multitasking performance in the multi-attribute task battery. Neuropsychologia 2022, 174, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, N.; Hirst, A.; de Fockert, J.W.; Viding, E. Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2004, 133, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G.B.; Nygren, T.E. The subjective workload assessment technique: A scaling procedure for measuring mental workload. In Advances in Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 52, pp. 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th ed.; Administration and Scoring Manual; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open-source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, S.D.; Dirckx, S.G.; Niazy, R.K.; Iannetti, G.D.; Wise, R.G. EEG signatures of auditory activity correlate with simultaneously recorded fMRI responses in humans. NeuroImage 2010, 49, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, N.; Hofmann, C.; Deneke, M.; Schmitz, B. Integrating cognitive load theory and concepts of human–computer interaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhäuser, W.; Neubert, C.R.; Grimm, S.; Bendixen, A. High visual salience of alert signals can lead to a counterintuitive increase of reaction times. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, C.; Rashal, E.; Santandrea, E.; Ben Hamed, S.; Chelazzi, L.; Macaluso, E.; Boehler, C.N. The dynamics of statistical learning in visual search and its interaction with salience processing: An EEG study. NeuroImage 2024, 286, 120514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ede, F.; Chekroud, S.R.; Nobre, A.C. Human gaze tracks attentional focusing in memorized visual space. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Nobre, A.C.; van Ede, F. Microsaccades transiently lateralise EEG alpha activity. Prog. Neurobiol. 2023, 224, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyberg, S.; Werkle-Bergner, M.; Sommer, W.; Dimigen, O. Microsaccade-related brain potentials signal the focus of visuospatial attention. NeuroImage 2015, 104, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, E.F.; Peysakhovich, V.; Causse, M. Measuring the amplitude of the N100 component to predict the occurrence of the inattentional deafness phenomenon. In Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering; Hale, K.S., Stanney, K.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dehais, F.; Roy, R.N.; Gateau, T.; Scannella, S. Auditory alarm misperception in the cockpit: An EEG study of inattentional deafness. In International Conference on Augmented Cognition; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.-J.; Chen, W.-W.; Zhang, X. The neurophysiology of P 300—An integrated review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coull, J. Neural correlates of attention and arousal: Insights from electrophysiology, functional neuroimaging and psychopharmacology. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998, 55, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, A.; Gaspar, J.M.; McDonald, J.J. Tracking target and distractor processing in fixed-feature visual search: Evidence from human electrophysiology. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2013, 39, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, N. Distracted and confused?: Selective attention under load. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, N.; Tsal, Y. Perceptual load as a major determinant of the locus of selection in visual attention. Percept. Psychophys. 1994, 56, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Maanen, L.; van Rijn, H.; Borst, J.P. Stroop and picture—Word interference are two sides of the same coin. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2009, 16, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Flombaum, J.I.; McCandliss, B.D.; Thomas, K.M.; Posner, M.I. Cognitive and Brain Consequences of Conflict. NeuroImage 2003, 18, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, F.; Notebaert, W.; Liefooghe, B.; Vandierendonck, A. Stimulus- and response-conflict-induced cognitive control in the flanker task. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, G.D.; Gordon, R.D. Executive control of visual attention in dual-task situations. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.; Li, Y. Examining mental workload based on multiple physiological signals: Review of the multi-attribute task battery (MATB) technique. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2024, 24, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.M.; Gutzwiller, R.S.; Johnson, C.K. Priority influences task selection decisions in multi-task management. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 119, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, J.J.; Miller, S.H.B.; Nash, K.; Bruce, M.; Ashmead, D.; Shotwell, M.S.; Edworthy, J.R.; Wallace, M.T.; Weinger, M.B. Acoustic features of auditory medical alarms—An experimental study of alarm volume. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 143, 3688–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heiden, R.M.A.; Janssen, C.P.; Donker, S.F.; Hardeman, L.E.S.; Mans, K.; Kenemans, J.L. Susceptibility to audio signals during autonomous driving. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.W.; Montano, S.R. Response times to visual and auditory alarms during Anaesthesia. Anaesth. Intensiv. Care 1996, 24, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, E.A.M.; Gilbert, S.; Koval, I.; Wekenborg, M.K. Alarm fatigue in healthcare: A scoping review of definitions, influencing factors, and mitigation strategies. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.X. Selective visual processing across competition episodes: A theory of task-driven visual attention and working memory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Mahr, A.; Castronovo, S.; Theune, M.; Stahl, C.; Müller, C.A. Local danger warnings for drivers: The effect of modality and level of assistance on driver reaction. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Hong Kong, China, 7–10 February 2010; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.343 * (2.327) | 2.369 * (2.370) | 1.861 (1.947) |

| Control variables | |||

| Age | −0.066 (−1.564) | −0.068 (−1.627) | −0.047 (−1.192) |

| Gender | 0.385 * (2.016) | 0.398 * (2.101) | 0.441 * (2.472) |

| Main effect | |||

| Sustained negativity | −0.131 (−0.868) | −0.128 (−0.850) | −0.131 (−0.928) |

| ∆ACC | 0.924 (1.301) | 0.362 (0.519) | |

| Interaction | |||

| Sustained negativity × ∆ACC | −3.617 * (−2.664) | ||

| Sample Size | 49 | 49 | 49 |

| R2 | 0.162 | 0.193 | 0.308 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.106 | 0.120 | 0.227 |

| F Value | F(3,45) = 2.907, p = 0.045 | F(4,44) = 2.637, p = 0.047 | F(5,43) = 3.820, p = 0.006 |

| ∆R2 | 0.162 | 0.031 | 0.114 |

| ∆F Value | F(3,45) = 2.907, p = 0.045 | F(1,44) = 1.693, p = 0.200 | F(1,43) = 7.094, p = 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, B. Attentional Selection and Allocation to Alarm Signals in Complex Environments: The New Electrophysiological Evidence. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010012

Zhang J, Yang Y, Li B. Attentional Selection and Allocation to Alarm Signals in Complex Environments: The New Electrophysiological Evidence. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jia, Yang Yang, and Bingkun Li. 2026. "Attentional Selection and Allocation to Alarm Signals in Complex Environments: The New Electrophysiological Evidence" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010012

APA StyleZhang, J., Yang, Y., & Li, B. (2026). Attentional Selection and Allocation to Alarm Signals in Complex Environments: The New Electrophysiological Evidence. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010012