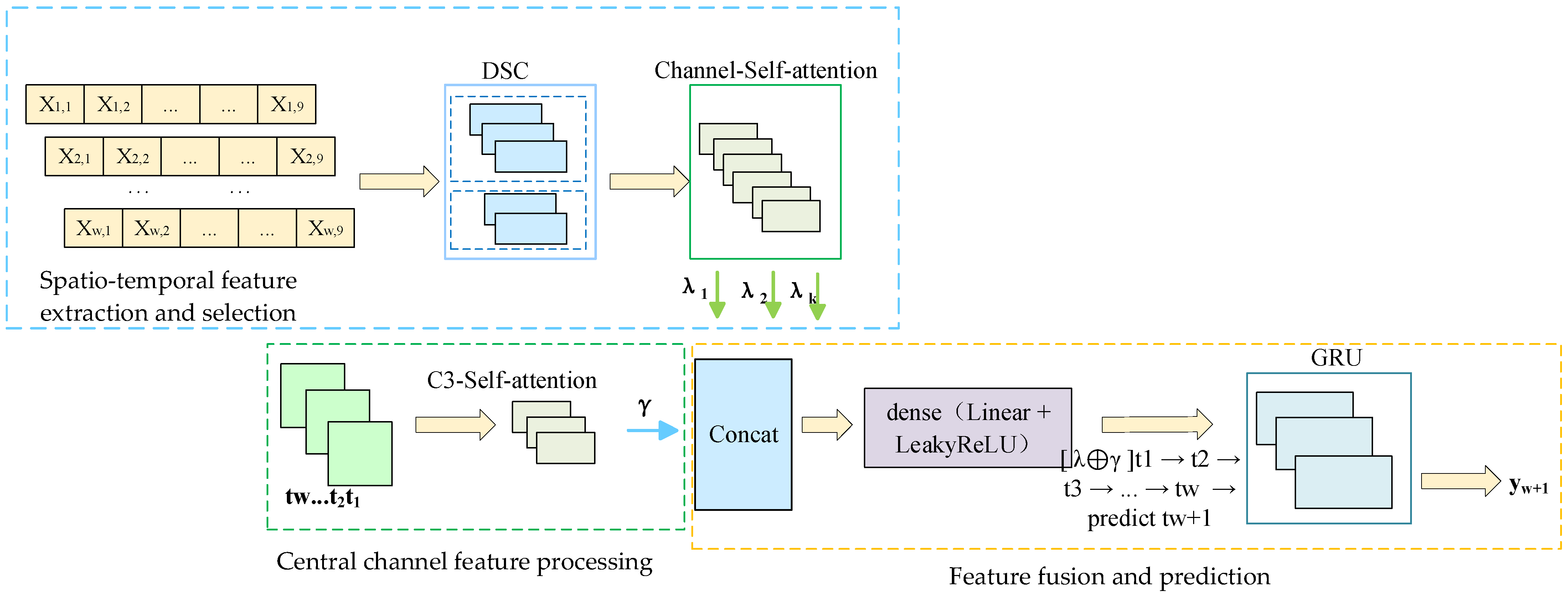

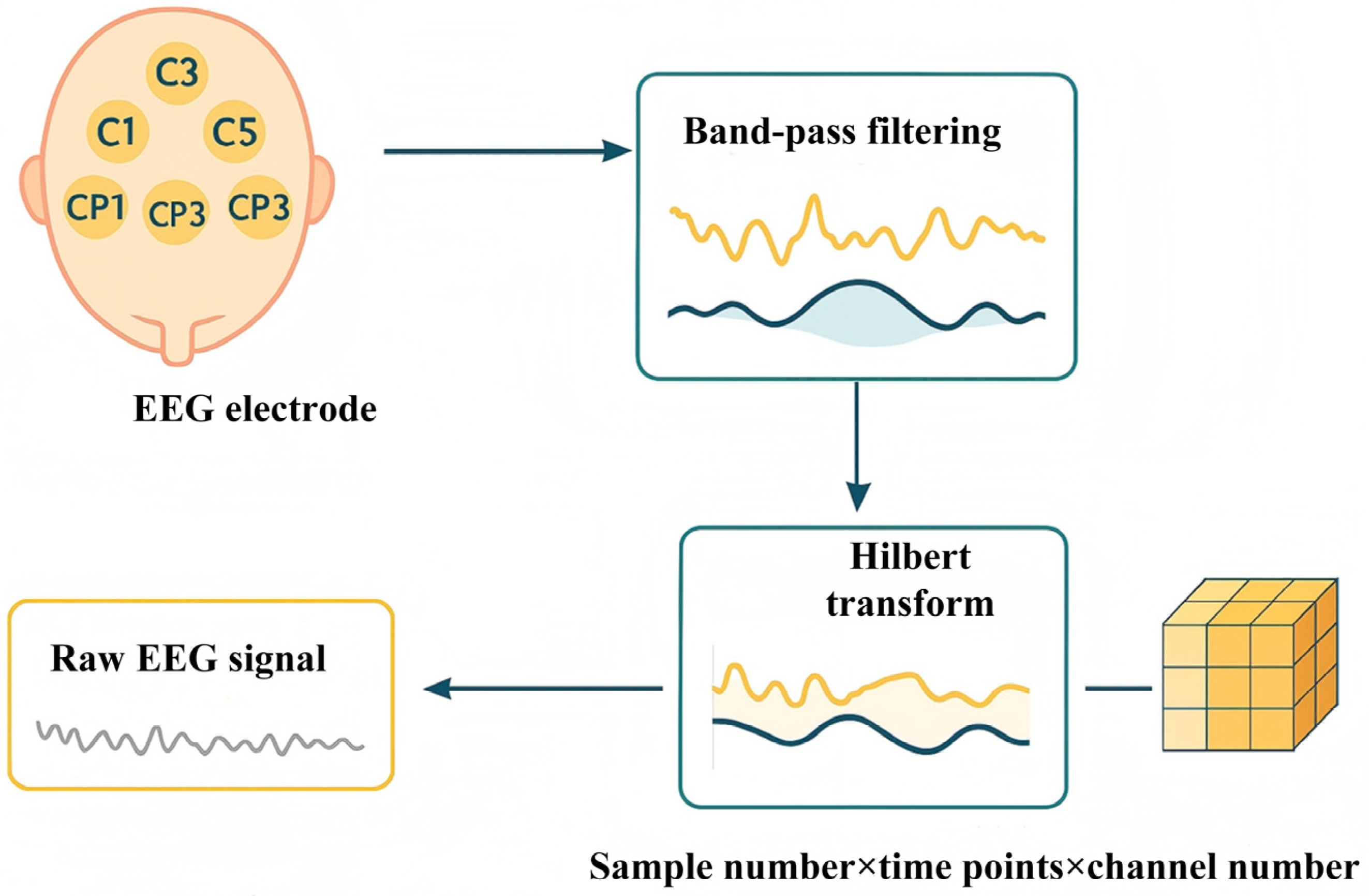

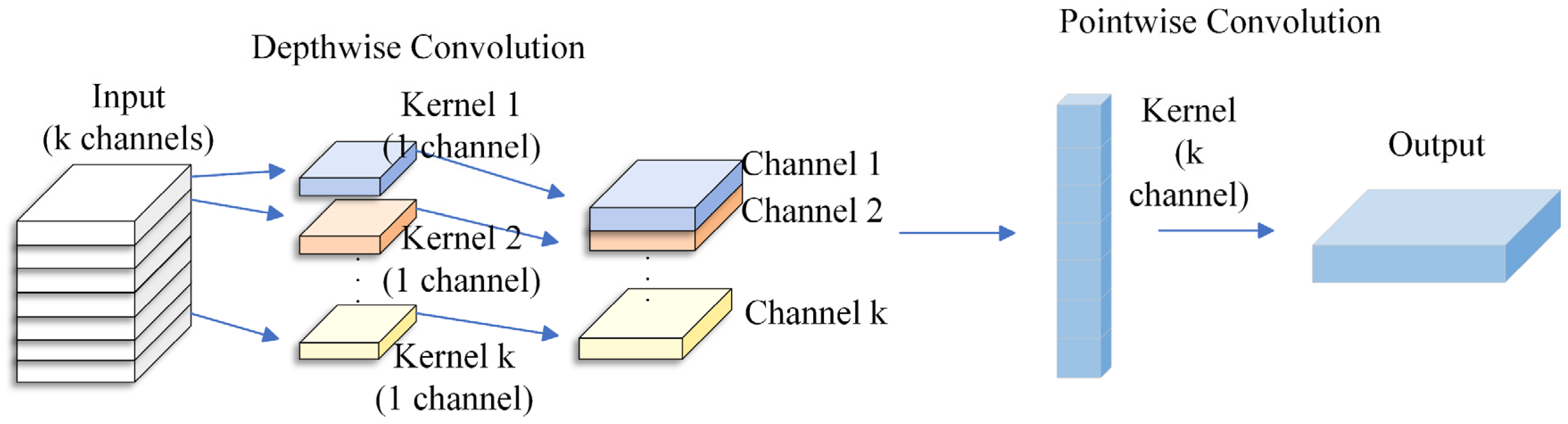

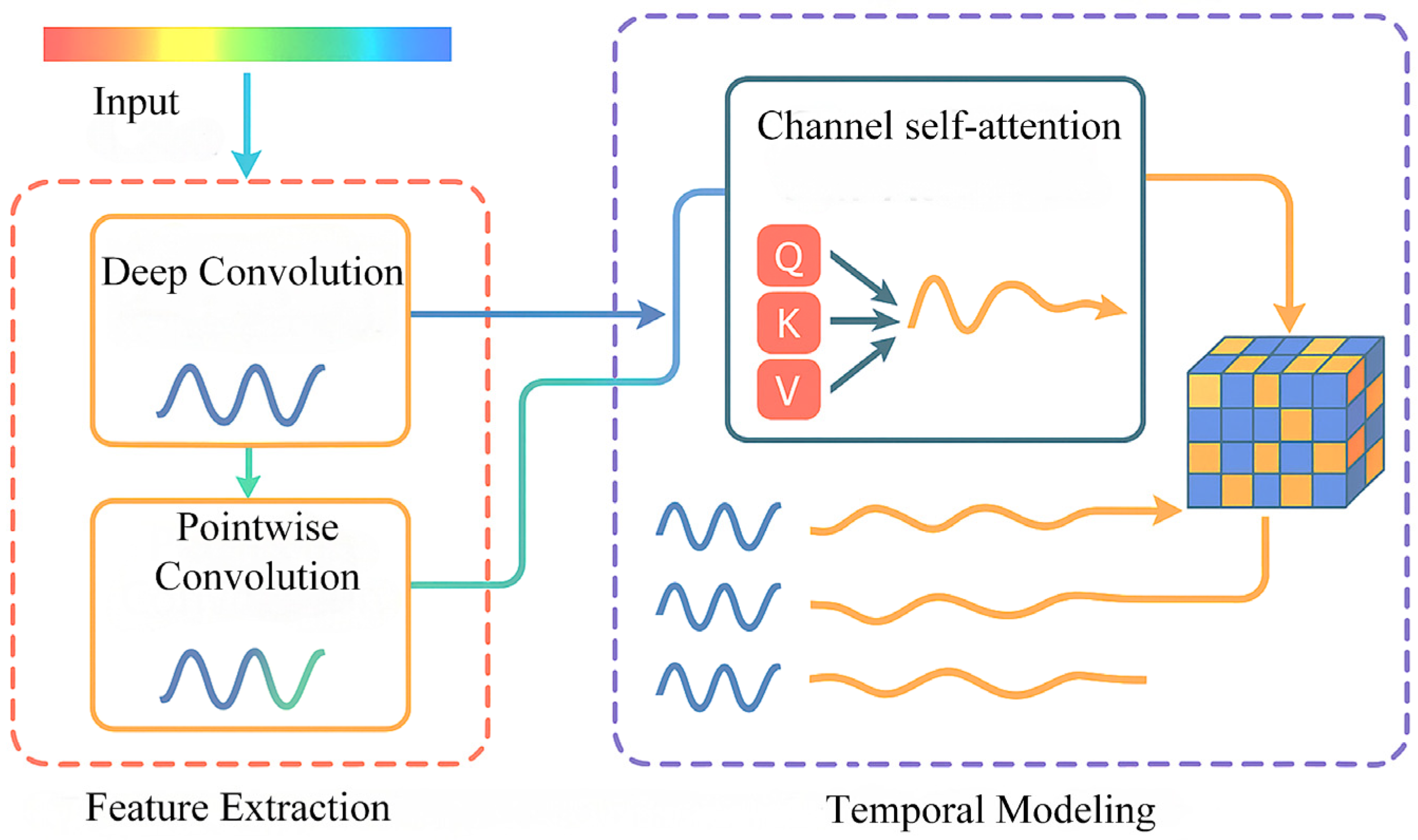

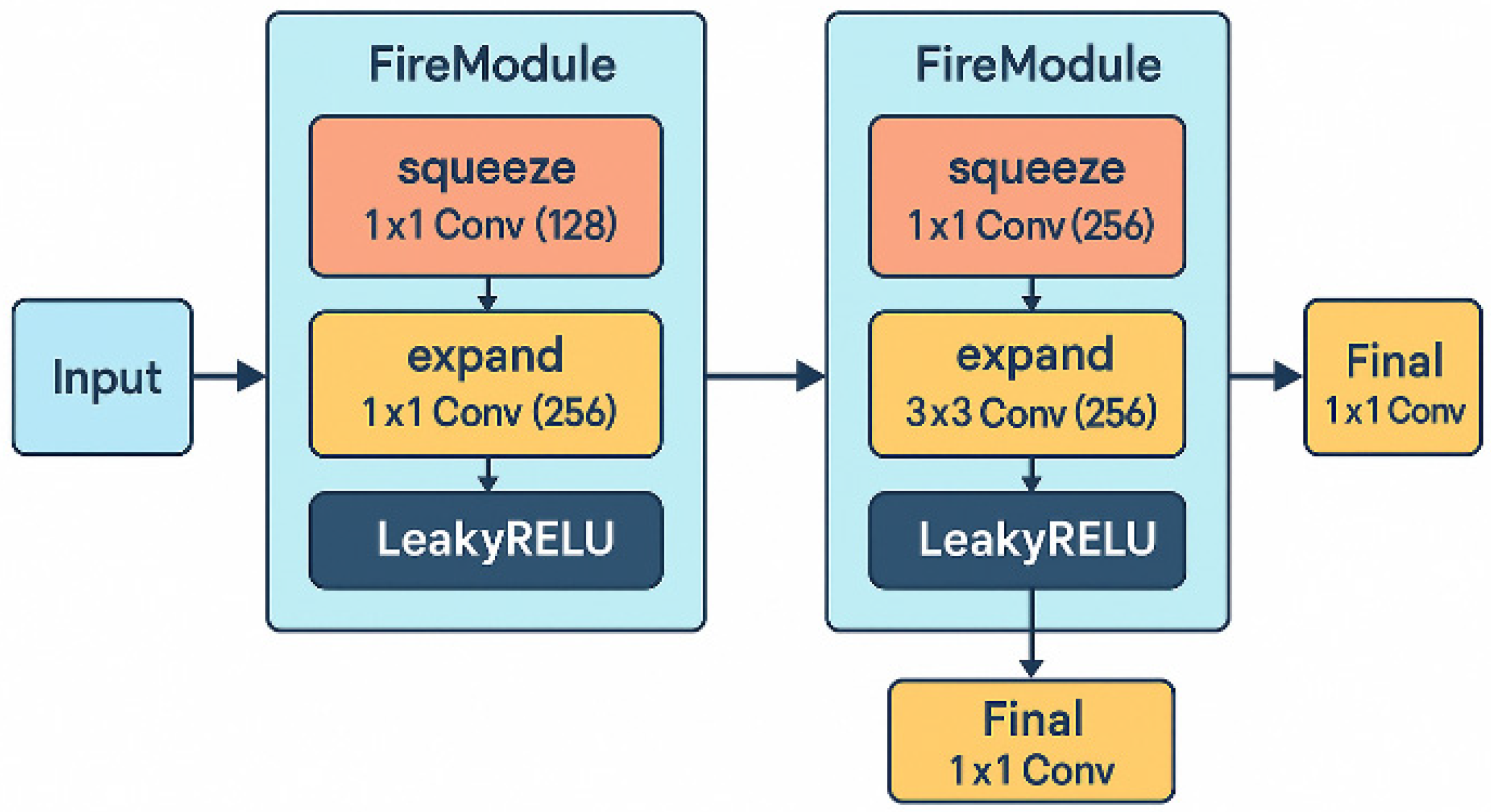

In order to solve the above problems, this paper constructs a DSC-Attention-GRU parallel phase prediction model, which integrates the spatial features extracted by deep separable convolution and the temporal features enhanced by the attention mechanism to realize multi-dimensional information integration, and provides an innovative solution to solve the phase prediction lag problem. The model consists of three modules: spatio-temporal feature extraction and selection, central channel feature processing, and feature fusion and prediction. In the spatial feature extraction and selection module, the spatial feature of each channel at each time point is obtained by convolution of in DSC, and the important spatial features are filtered by the self-attention mechanism. In the central channel feature processing module, the self-attention mechanism is used to interact and integrate information among elements in the sequence, and the attention weight to each element is dynamically adjusted, so as to capture the complex dependence relationship in the sequence; in the feature fusion and prediction module, the spatial features between each channel and the central channel feature are fused by using the full connection layer, and the fused features are input to GRU and the prediction result is output. To evaluate the cross-subject generalization ability of the model, this paper adopts a training/validation/testing strategy based on the random division of subjects. Specifically, all the subject data were divided into 12 training sets, three validation sets, and five test sets, which were, respectively, used for model training, hyperparameter validation, and generalization testing. There was no overlap among the subjects in each group. During the testing phase, the model performs feature extraction and prediction for each unseen subject individually and calculates its prediction performance in terms of the instantaneous phase. The generalization performance of the model in non-individualized scenarios was evaluated by the system through average performance metrics (including PLV, APE, MAE, RMSE, and MLT) on multiple independent test subjects. The model was trained with Adam and an MSE loss. The initial learning rate is 1 × 10

−5. If the loss does not improve after 10 consecutive validations, ReduceLROnPlateau will reduce it by 10 times. Set the epoch to 400, random seed to 0, and the batch size to 32. We report model complexity in terms of the number of trainable parameters and computational cost measured by MACs/FLOPs for a single forward pass under the same input setting, together with inference latency on our hardware. The proposed DSC-Attention-GRU contains approximately 7.37M trainable parameters (about 29.5 MB in FP32), with the majority of parameters contributed by the pointwise convolution and the GRU layer, while the attention modules add a negligible number of parameters.

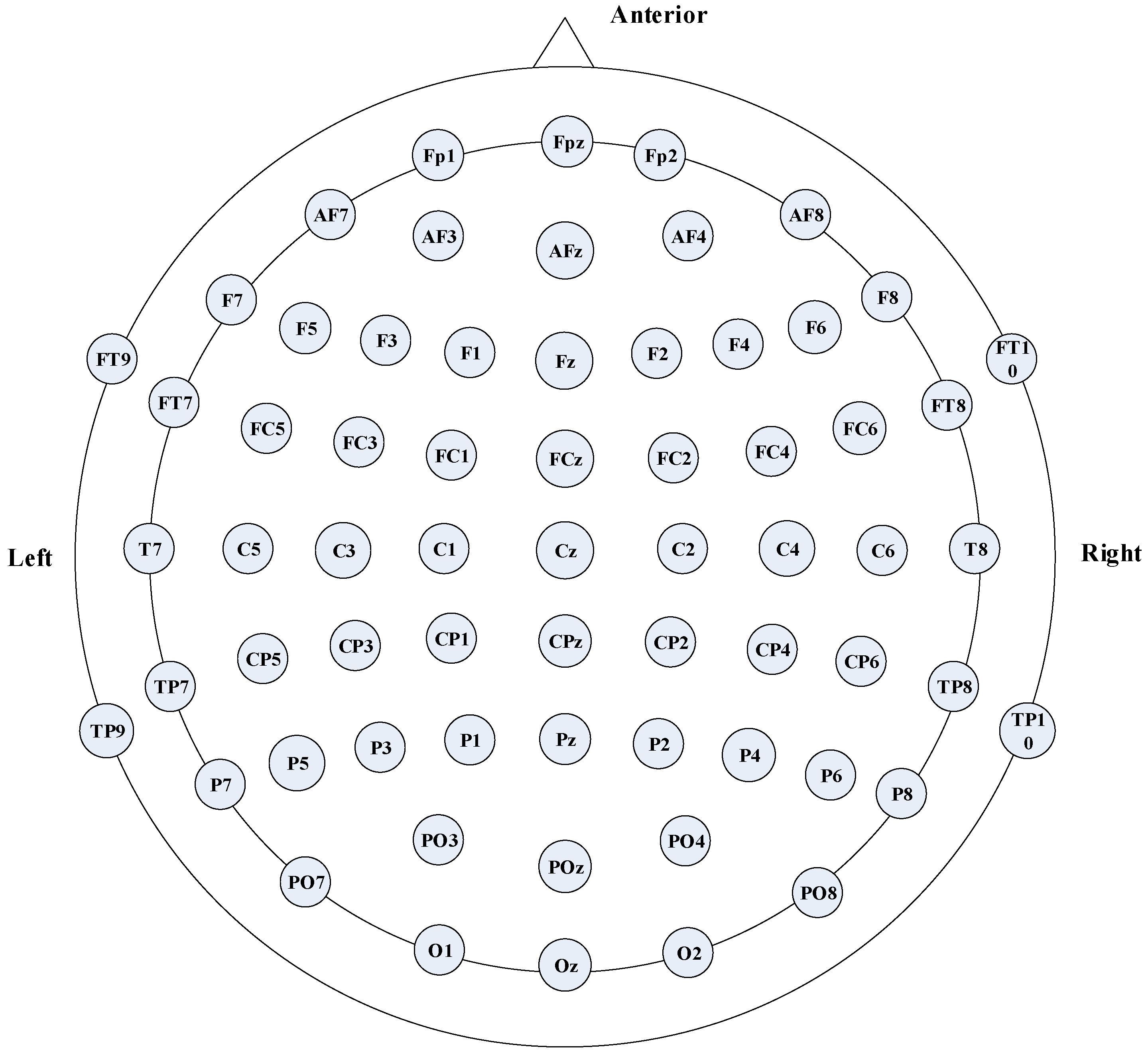

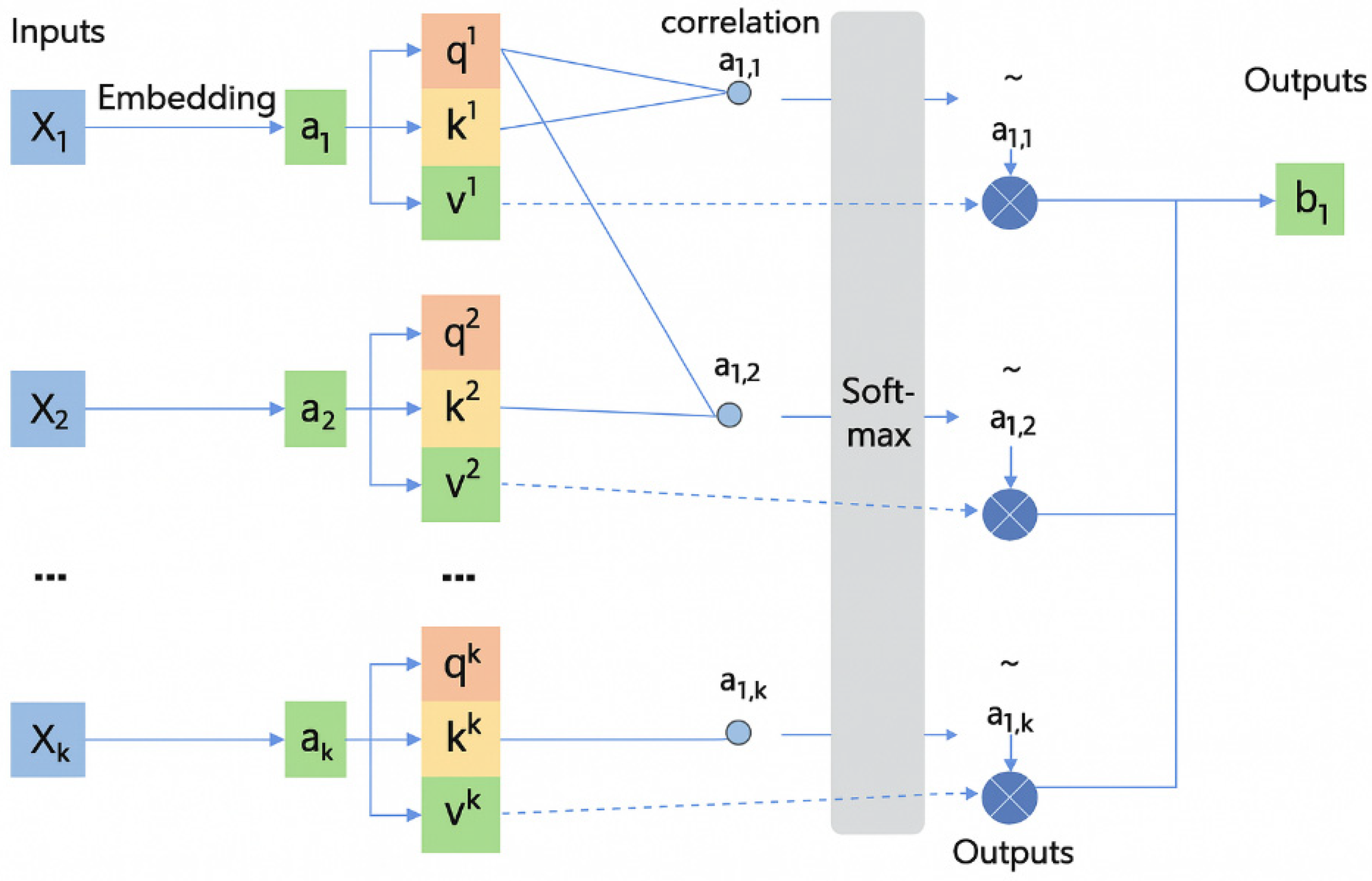

Figure 3 represents data from channel

j at time

i,

,

;

represents features from the central channel;

represents spatial features.

4.4. Validation of Model Validity

In terms of model validity verification, six differential models were constructed based on the central channel and the surrounding eight channel data of the subjects, and the multi-feature extraction components such as DSC and the self-attention mechanism were fused, and the time series modeling units such as LSTM, GRU, and WavNet were combined. This was to verify the effectiveness of the module we selected and ensure that the experimental detail designs of other models are consistent with DSC-Attention-GRU. The ablation experiment was designed to explore the performance of each model module combination in the EEG phase prediction task systematically by using different stimulation intensity and EEG frequency band data, so as to provide a multi-dimensional and refined experimental basis for screening the optimal prediction model.

In this process, the performance of six models in terms of subthreshold stimulation α frequency band data was examined. The specific results are presented in

Table 5.

The PLV of both the DSC-LSTM and DSC-Attention-GRU models are higher than those of the C3-Attention-LSTM model. This indicates that the DSC module can effectively reduce feature redundancy and suppress noise interference. While reducing the MAE and RMSE, the performance of the model in feature semantic recognition and noise resistance is improved, enhancing the robustness of the model.

From the perspective of model performance comparison, the comprehensive performance of DSC-LSTM is superior to that of DSC-Attention-LSTM. Analyzing the reasons, although the signal in this task scenario is relatively stable, the proportion of background noise is relatively high. At this time, the attention mechanism not only fails to function to improve the model performance, but also increases the model complexity by introducing additional parameter calculations, while amplifying the negative impact of noise interference. In contrast, DSC-LSTM, with its simple and efficient LSTM network structure, can stably capture the phase variation patterns in such relatively simple tasks, thereby maintaining a low APE, MAE, and RMSE. It is worth noting that although the DSC-Attention-LSTM model achieved a relatively high PLV, its prediction accuracy did not improve simultaneously. Instead, it may experience a decline in overall performance due to improper distribution of attention weights and excessive focus on local features. This also confirms that the attention mechanism is more suitable for the precise capture of local detail features. The cross-model comparison results further indicate that the synergistic effect of the DSC module and the attention mechanism can more accurately fit the dynamic patterns of complex time series. Among them, the DSC-Attention-GRU model achieves the optimal balance between PLV and error control, and its anti-noise ability is particularly outstanding. Relying on the parameter simplification advantage of the GRU architecture, combined with the feature purification of DSC and the detail-focusing ability of attention, this model ultimately achieves a dual optimization of prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. DSC-Attention-GRU consistently reduces the mean peak/trough timing lag by 0.21–0.25 ms (2.7–3.2%) relative to the baselines, indicating improved peak/trough temporal alignment and alleviated phase-lag effects.

In summary, the DSC module lays a high-quality feature foundation for the model, the attention mechanism enhances the ability to capture local key features, and the GRU architecture ensures the efficiency of time series modeling. The organic integration of the three makes the DSC-Attention-GRU model slightly superior to other comparison models in terms of prediction accuracy, robustness, and efficiency.

When the EEG signals were subjected to suprathreshold stimulation intensity (i.e., stimulation intensity exceeding threshold), the evoked EEG signals were analyzed. The performance of the six models in α frequency band data is shown in

Table 6.

The APE of DSC-Attention-LSTM is 13% lower than that of Attention-LSTM, indicating that DSC can improve the prediction accuracy. The APE of DSC-LSTM is 44.8% lower than that of C3-Attention-LSTM (without DSC), indicating that DSC can reduce error by optimizing feature representation. The PLV of the model with DSC is close to 1.000, which shows that DSC enhances the robustness of the model and reduces the fluctuation. APE and MAE of DSC-Attention-LSTM decreased by 85.3% and 83.4%, respectively, compared with DSC-LSTM, indicating that the attention mechanism can reduce redundant information interference. DSC-Attention-GRU is optimal on all error metrics, significantly lower than DSC-Attention-LSTM on multiple metrics, and lower than DSC-Attention-WavNet on MAE and RMSE, proving that the GRU architecture combined with DSC and Attention is more suitable for tasks. GRU is a lightweight, improved version of LSTM with low computational complexity and the ability to model long sequence dependencies. DSC-Attention-GRU has high precision, high efficiency, and strong generalization, and has significant advantages in time series prediction. DSC-Attention-GRU consistently reduces the mean peak and trough timing lag by 0.20–0.23 ms (2.6–2.9%) compared with the baselines, indicating improved peak and trough temporal alignment and alleviated phase-lag effects.

When the EEG signals were subjected to subthreshold stimulus intensity, the evoked EEG signals were analyzed. The performance of the six models in β frequency band data is shown in

Table 7.

Comparing the PLV of DSC-Attention-LSTM and C3-Attention-LSTM, the PLV of the model with DSC is full score, and the PLV of the model without DSC is slightly lower, which indicates that DSC is very important to improve the stability of the basic performance of the model. Comparing the PLV of DSC LSTM and Attention LSTM, they are the same, but the error index of DSC LSTM is higher than DSC Attention LSTM, indicating that DSC needs attention to achieve the optimal effect. Compared with DSC-LSTM, APE, MAE, and RMSE decreased by 69.0%, 18.0%, and 22.8%, respectively, after attention was introduced, which proved that attention could improve the prediction accuracy. DSC-Attention-WavNet can reduce the error significantly compared with DSC-LSTM under different underlying networks, indicating that its effect is universal. DSC-Attention-GRU keeps the PLV full score, while the error index is leading in an all-round way. GRU realizes a balance between accuracy and efficiency, which is the optimal scheme for multi-component cooperation. DSC-Attention-GRU consistently reduces the mean peak/trough timing lag by approximately 0.21–0.23 ms (about 2.7–2.9%) compared with the baseline methods, indicating improved temporal alignment of peaks and troughs and thus an alleviated phase-lag effect.

When the EEG signals were subjected to suprathreshold stimulation intensity, the evoked EEG signals were analyzed. The performance of the above six models in terms of β frequency band data is shown in

Table 8.

Compared with DSC-LSTM, PLV increased from 0.9988 to 0.9996, and RMSE decreased from 0.0490 to 0.0294, indicating that the attention mechanism can optimize the extraction ability of important information by dynamic weight allocation. DSC-Attention-GRU is superior to DSC-Attention-LSTM and other baseline models. It inherits the core advantages of DSC-Attention and realizes a balance between accuracy and efficiency by using the high efficiency of GRU. In terms of temporal alignment, DSC-Attention-GRU achieves the lowest mean lag time (MLT = 7.5026 ms), reducing the peak/trough lag by 0.26–0.28 ms (3.4–3.6%) compared with the LSTM- and WavNet-based baselines (MLT ≈ 7.77–7.79 ms), indicating improved peak/trough timing alignment and alleviated phase-lag effects.

4.4.1. Statistical Analysis

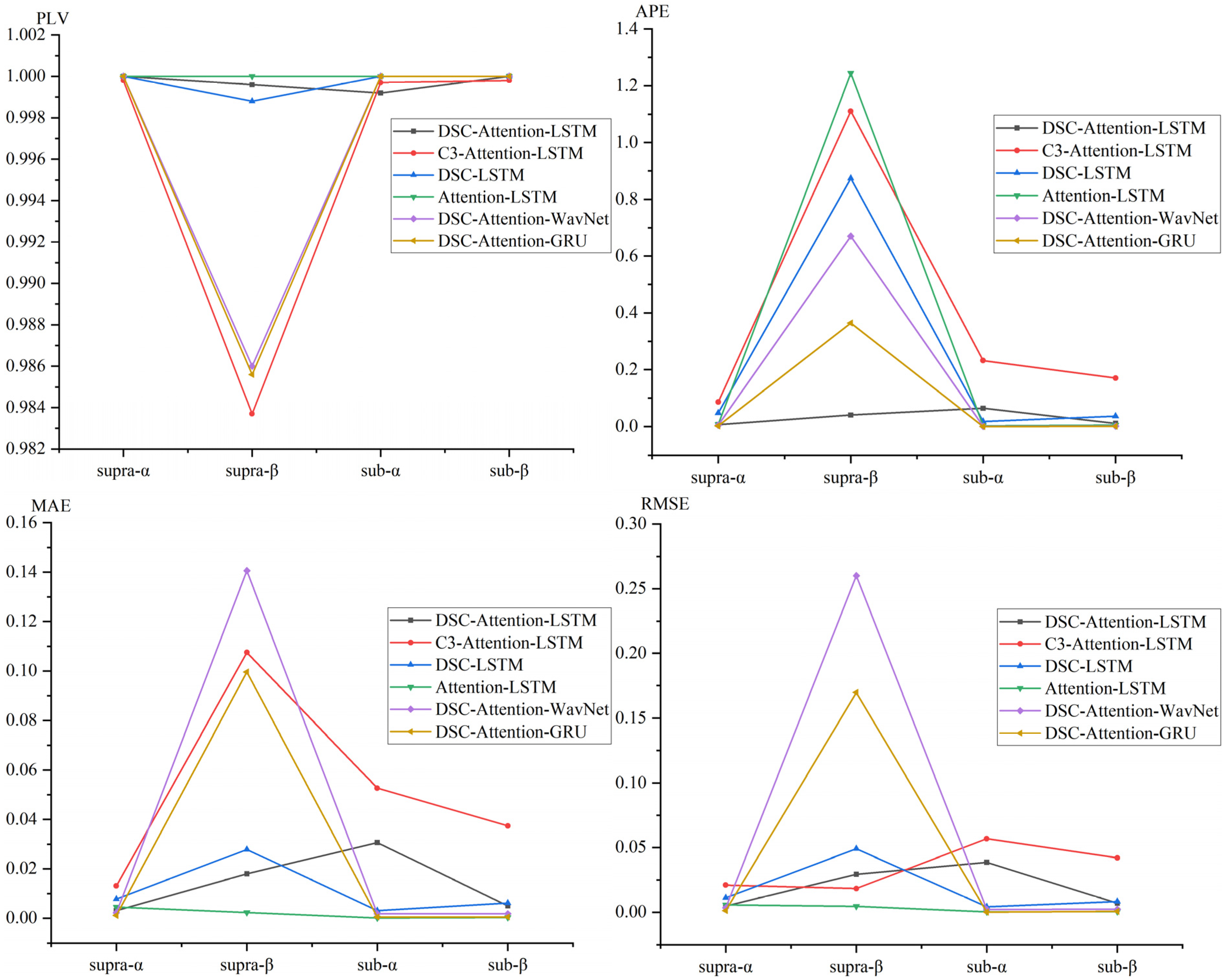

We evaluated EEG phase prediction under TMS across four experimental conditions defined by stimulation intensity and frequency band, using PLV, APE, MAE, and RMSE to compare six deep learning models and visualize performance trends, as shown in

Figure 8.

The figure shows that DSC-Attention-GRU achieved the best and most consistent performance across nearly all conditions, typically producing the lowest APE and MAE and maintaining PLV values close to 1, indicating accurate and stable phase tracking. In supra-α and sub-α, its APE was near zero with PLV close to 1, and even in the more challenging supra-β condition it remained stable, with only modest RMSE increases while keeping PLV above 0.98. In contrast, several baselines, such as C3-Attention-LSTM and Attention-LSTM, showed pronounced performance degradation in higher-frequency conditions, with APE exceeding 1.0 and PLV dropping substantially. Collectively, these results indicate that DSC-Attention-GRU offers stronger robustness and generalizability across stimulation states, supporting its suitability for real-time closed-loop TMS applications requiring reliable EEG phase tracking.

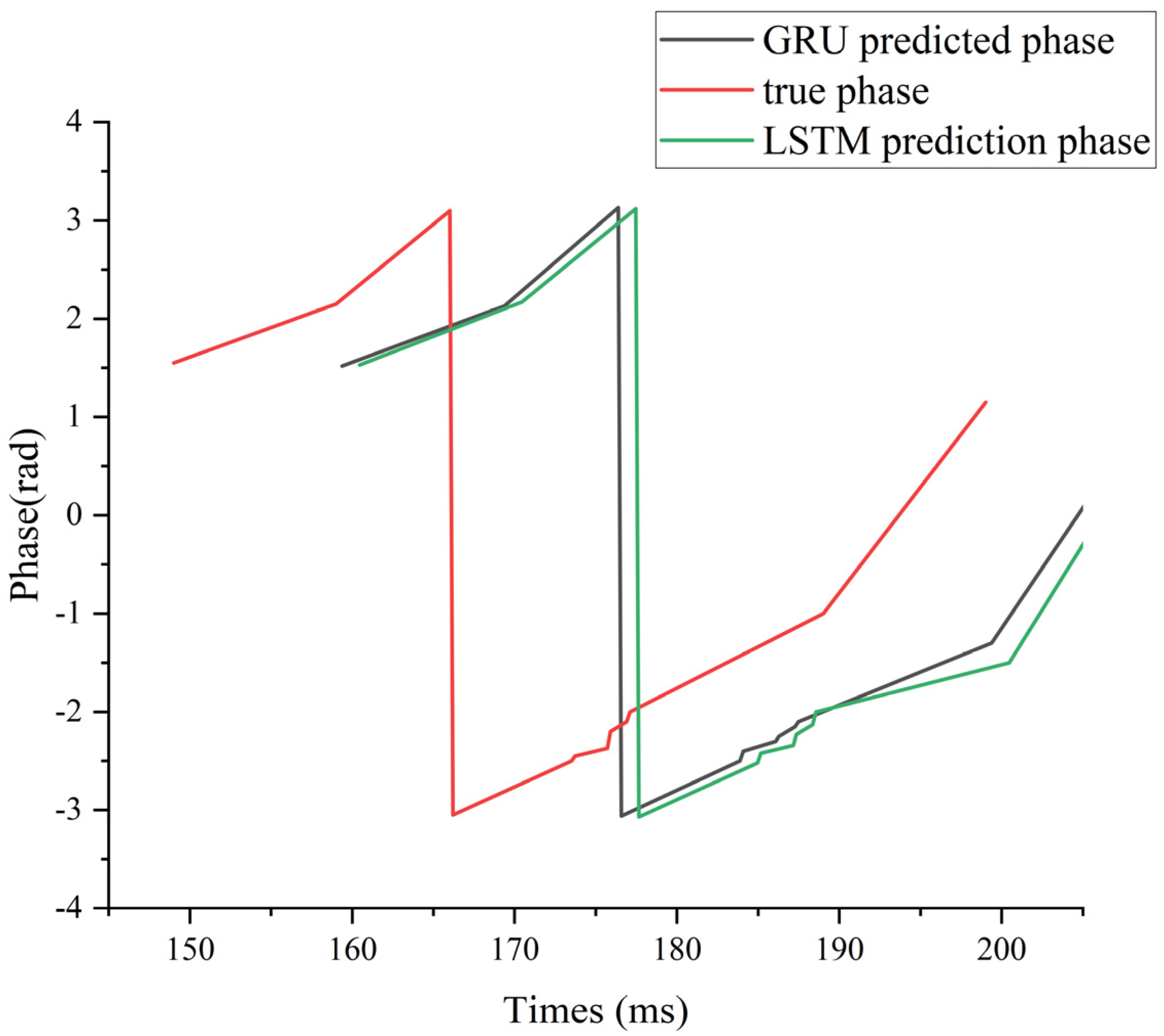

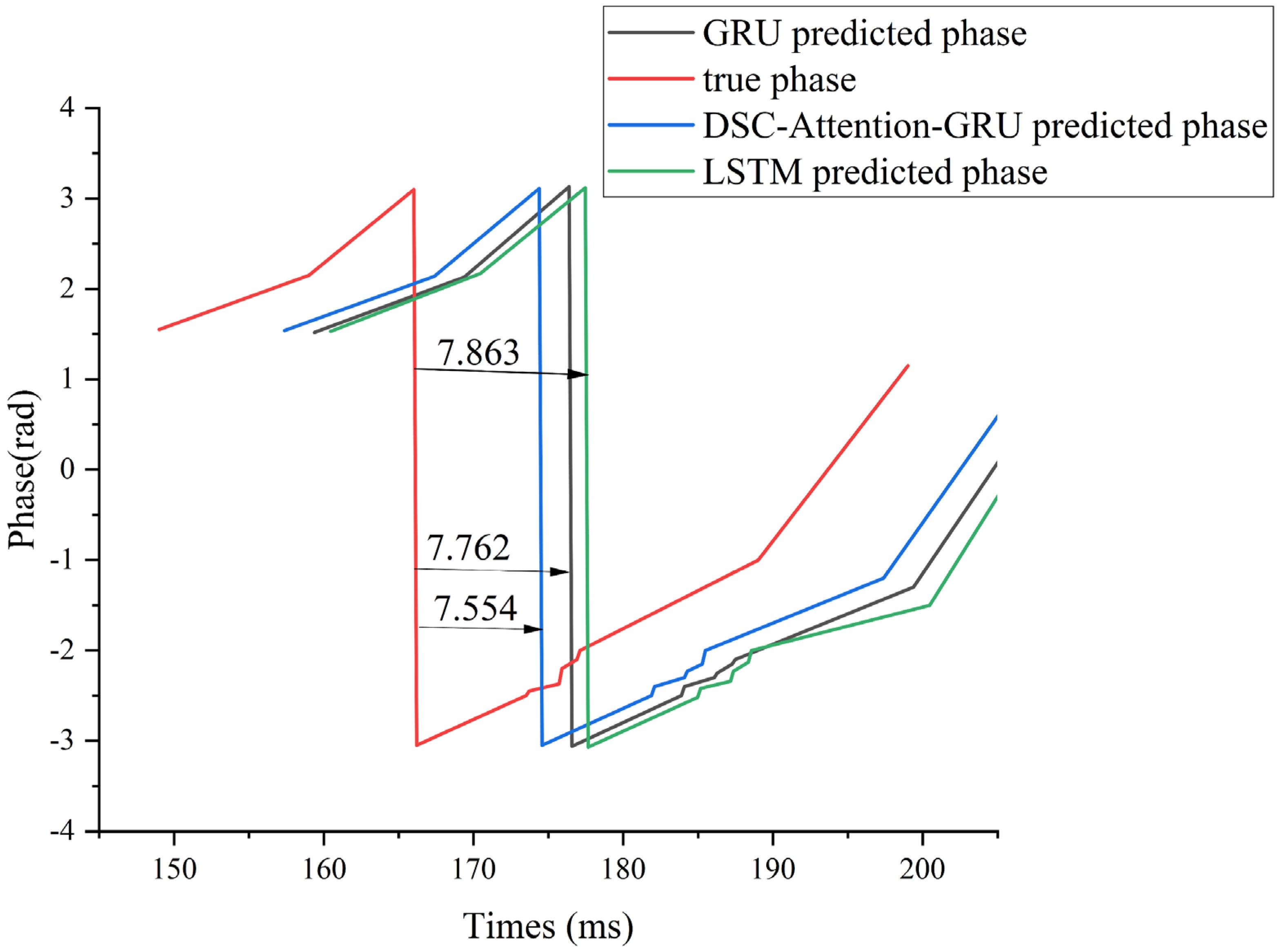

To illustrate this lag effect more intuitively, we use subject 006 under supra-α as an example. We mainly compared the phase hysteresis analysis of GRU, LSTM, and DSC-Attention-GRU with the real phase curve, as shown in

Figure 9.

Compared with the true phase, the DSC-Attention-GRU model lags behind by an average of 7.554 ms in peak-trough value prediction. This lag is relatively small and can more accurately track the changes in the actual phase, especially at moments when the phase changes sharply. In contrast, the average lag of GRU is 7.762 ms, and that of LSTM is 7.863 ms. The lag of both is slightly greater than that of DSC-Attention-GRU. Especially when dealing with rapidly changing stages, they cannot capture phase transitions in a timely manner like DSC-Attention-GRU. Overall, DSC-Attention-GRU effectively enhances its time series modeling capability by integrating depth-separable convolution and self-attention mechanisms. It can reduce lag and be more sensitive to dynamic responses, thereby achieving higher peak-trough prediction accuracy and stronger real-time prediction capabilities.

4.4.2. Comparison Experiment

To verify the effectiveness of the DSC-Attention-GRU model proposed in this paper, the EEG Phase Prediction Network (EPN) was selected as the comparison model in this study. EPN is a model specifically designed for EEG phase prediction tasks and can be directly applied to closed-loop neural regulation systems, especially suitable for the combined experimental paradigm of TMS-EEG. The core objective of this model lies in enhancing the accuracy of EEG phase prediction. The core requirement of the TMS-EEG closed-loop system is precisely to accurately select the timing of TMS stimulation based on the real-time predicted EEG phase. Therefore, EPN can efficiently predict the instantaneous phase of EEG signals, and provide key technical support for the timing regulation of TMS stimulation. The specific results are shown in

Table 9.

These results indicate that, although EPN is specifically designed for online EEG phase prediction, our architecture (which combines depthwise convolution, channel-wise self-attention, and GRU-based temporal modeling) provides better phase prediction accuracy and stability across subjects in the present TMS-EEG setting. DSC-Attention-GRU consistently achieves lower MLT than EPN across all stimulation intensities and bands (e.g., 7.5026 vs 7.5761 ms in supra-β), indicating improved peak/trough temporal alignment and alleviated phase-lag effects.