Versatility of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Review of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

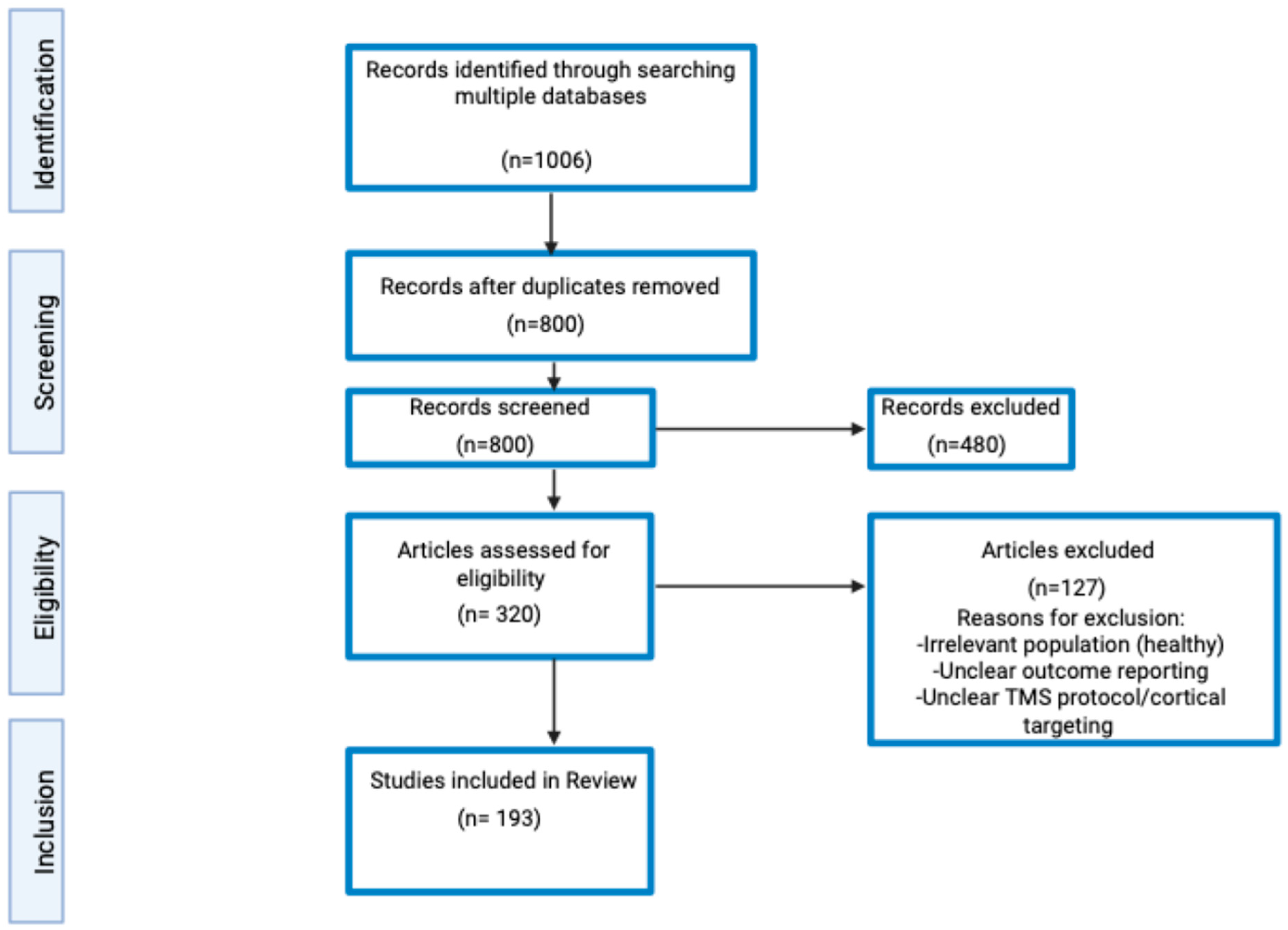

2. Literature Search Methodology

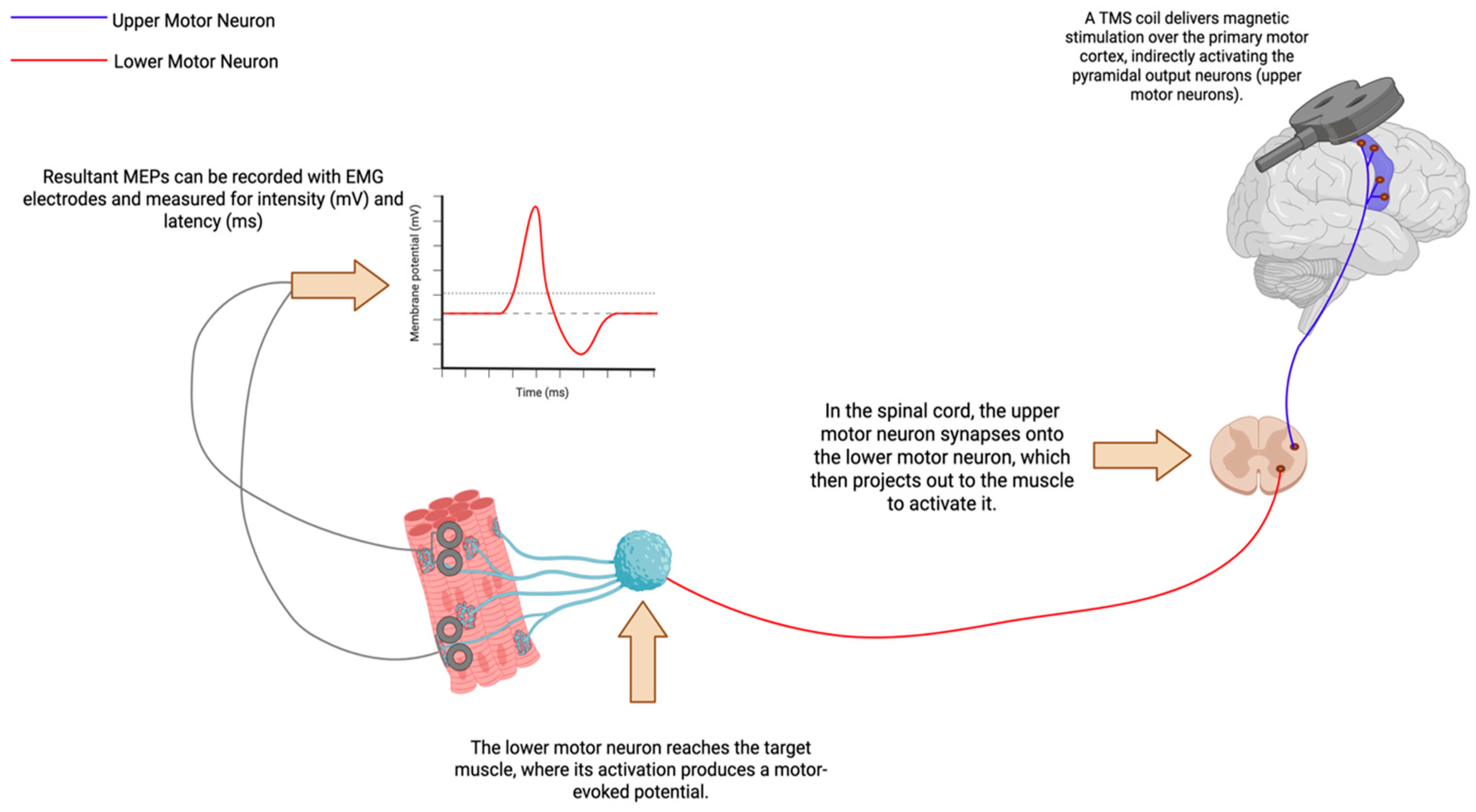

3. TMS Outcome Measures

3.1. Measures of Corticospinal Tracts

3.1.1. Motor Thresholds

3.1.2. Input–Output Curve

3.1.3. Cortical Silent Period

3.2. Measures of Intracortical Circuits Through Paired-Pulse Paradigms

3.2.1. Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition

3.2.2. Short-Interval Intracortical Facilitation

3.2.3. Long-Interval Intracortical Inhibition

3.2.4. Intracortical Facilitation

3.2.5. Interhemispheric Inhibition

3.2.6. Short-Latency Afferent Inhibition

3.2.7. Long-Latency Afferent Inhibition

3.2.8. Cerebellar Inhibition

4. Diagnostic Utility of TMS Abnormalities in Neurological Diseases (Table 1)

| Condition | Unique TMS Outcomes | Prospective Value |

|---|---|---|

| Parkinson’s Disease (PD) | SICI ↓ ⟷ * CSP duration ⟷ ↓ LICI (⟷ ↓ ↑) * SICF ↑ ICF ⟷ ↓ AMT⟷ ↓ (Symptomatic influence) RMT ⟷ ↓ (Symtpomatic influence) I/O ↑ (Steeper curve at rest) SAI ↓ (disease progression + dopaminergic therapy) ⟷ ↑ (in patients not receiving dopaminergic therapy) CSP duration ⟷ ↓ ISP duration ⟷ ↓ LIHI ↓ SIHI ⟷ ↓ | SAI may help predict the development of Parkinson’s disease-related dementia and the risk of falls. Potential for SICI and SICF to serve as biomarkers for tracking disease progression. |

| Dystonia | RMT ⟷ I/O ⟷ SICI ↓ ⟷ * LICI ↓ (rest) ⟷ ↑ ↓ (active) * ICF ↓ (sometimes absent) CSP ↓ SIHI, LIHI ↓ (with mirror movements + severity dependent) LAI, SAI ↓ ⟷ (subtype dependent) Surround inhibition ↓ CBI ↓ ⟷ (subtype dependent + severity dependent) | Diagnostic value remains limited, and further research is needed to clarify differences across subtypes. |

| Essential Tremor (ET) | CBI (↓ ⟷) * SICI (↓ ⟷) * SAI ↑ (time dependent) LICI ⟷ ↓ (stimulation dependent) RMT (↑ ↓, drug dependent) * AMT ↓ * I/O (⟷ ↓) * CSP ⟷ | Diagnostic value remains limited, and additional research is needed, particularly on drug interactions. |

| Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) | RMT, AMT ↓ (severity dependant) CSP duration ⟷ SICI (⟷) ↓ (time dependent) * ICF ↓ LICI (↓ ⟷) * CSP ⟷ SAI ↓ (normalized with dopaminergic and cholinergic therapies) | TMS-based profiles using multiple outcome measures can distinguish AD from other neurodegenerative disorders with up to 92% accuracy. |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) | RMT, AMT ↓ (apparent, but statistically non-significant) SICI ⟷ ICF ⟷ LICI ⟷ SAI ↓ (subtype dependent) | The SICI-ICF/SAI ratio has been shown to differentiate AD-related MCI from non-AD MCI with 90% accuracy, performing comparably to amyloid biomarkers. |

4.1. Parkinson’s Disease

4.2. Dystonia

4.3. Essential Tremor

4.4. Alzheimer’s Diseases and Mild Cognitive Impairment

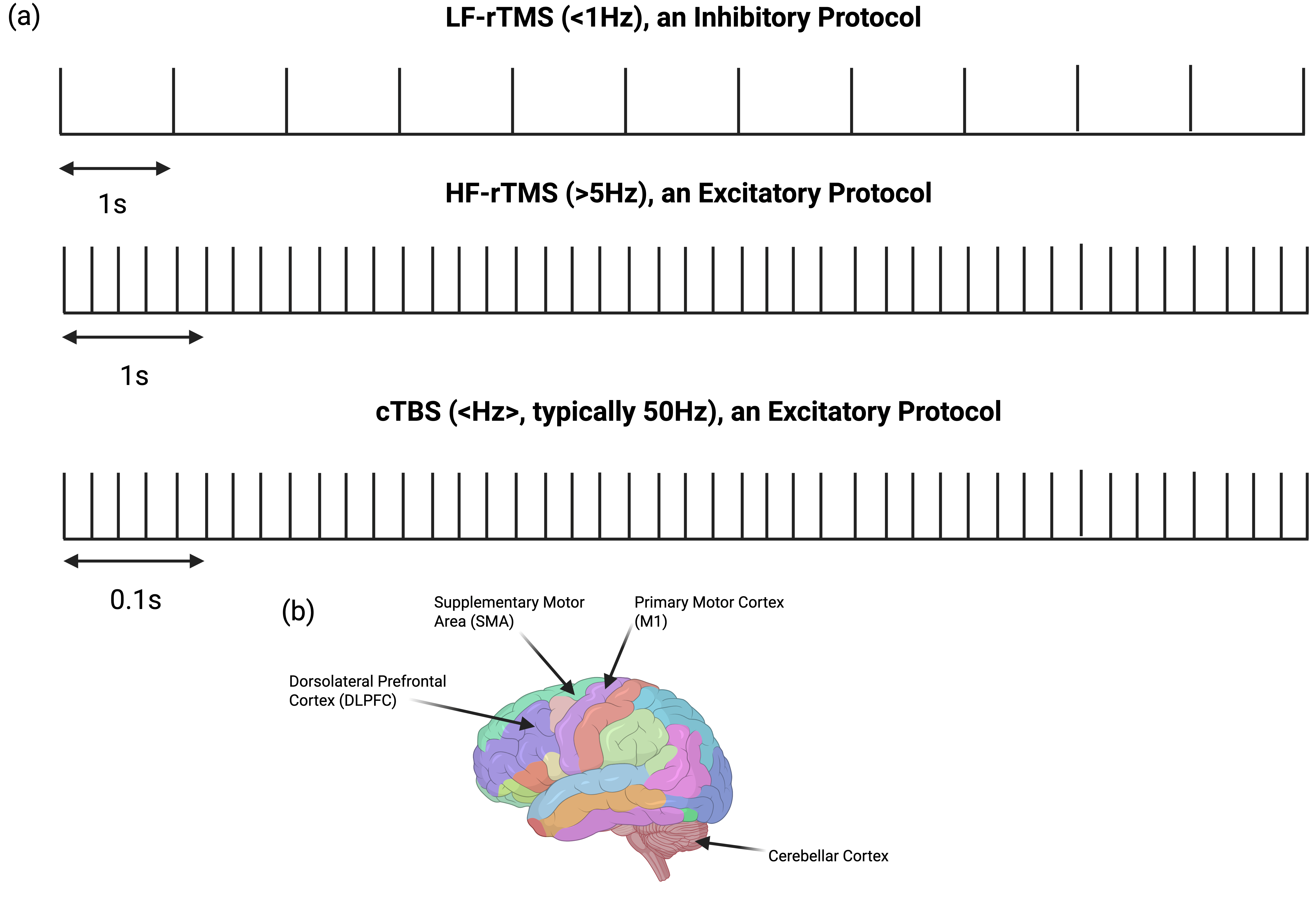

5. rTMS in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders (Table 2)

5.1. Parkinson’s Disease

5.1.1. High-Frequency (>5 Hz) rTMS for Motor Symptoms

5.1.2. Low-Frequency (<1 Hz) rTMS for Motor Symptoms

5.2. Dystonia

5.3. Essential Tremor

5.4. Alzheimer’s Disease + Mild Cognitive Impairment

| Condition | Parameter | Effect + Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Parkinson’s Disease (PD) | High frequency over M1 (5 Hz). | Short-term improvements in motor function in upper-limb contralateral to stimulation stie (↓ UPDRS-III scores, (p = 0.0005) [262]. |

| Long-term (≤1 month) improvements in motor function (↓ UPDRS-III scores (p = 0.0001), ↑ walking speed (p = 0.001), and self-assessment scales (p = 0.002)) [263]. | ||

| Improvements in motor and mood symptoms and LID [23,265,266,267,268,278]. | ||

| Resorted excitatory circuits reduced bradykinesia, improved rigidity (↑ ICF and prolonged CSP) [127]. | ||

| Improvement in FOG symptoms (improved Standing Start 180° Turn Test and FOG-Q scores, ↓ UPDRS-III scores, and ↓ TUG score (p < 0.05)) [277,278]. | ||

| Improvement in gait speed, stride length, and variability of gait speed (p < 0.05) [280]. | ||

| Restored (↑) SICI (p = 0.001) [280]. | ||

| High frequency over broader motor cortex regions (limb-specific) (>5 Hz). | Improvements in motor symptoms and LID (p < 0.001) [267]. | |

| High frequency (>5 Hz) over left-DLPFC. | Improvements in motor function, mood symptoms, and LID [265]. | |

| Improvement in gait and upper limb bradykinesia (p < 0.001) [281]. | ||

| High frequency over SMA (>5 Hz). | Improvements in LID [265,268]. | |

| Restoration of the basal ganglia–thalamocortical circuitry and motor function (↓ UPDRS-III scores (p < 0.0001) [271]. | ||

| Improvements in general motor symptoms (↓ UPDRS-III scores (p = 0.0001) [272]. | ||

| Restored intracortical inhibition (↑SICI, ↑ LICI, and ↑ CSP) [127] | ||

| Improvements in motor symptoms. | ||

| Low frequency over M1, right- and left-DLPFC, and SMA (<1 Hz). | Improvements in motor symptoms (↓ UPDRS-III scores (p < 0.05, p < 0.0001, p < 0.05, p < 0.001)) [272,285,286,287,288]. | |

| Improvements in non-motor symptoms (↑ executive function (p < 0.0001) ↓ NMSQ score (p < 0.0001) ↓ HRSD (p < 0.0001)) [286,288]. | ||

| Dystonia | Low frequency over contralateral dPMC: (≤1 Hz) | Improvements in writing and motor control (focal hand dystonia) (p = 0.004) [296,297]. |

| Improvements in sensory discrimination (improved Byl–Cheney–Boczai sensory discriminator (p = 0.017) [298]. | ||

| Improvements in functional disability (improved ADDS (p = 0.048) [298]. | ||

| High frequency (50 Hz) cTBS over contralateral dPMC: (50 Hz) | Restoration of abnormal dPMC-M1 connectivity (p < 0.001) [299]. | |

| ↑ SICI (p < 0.001) [299]. | ||

| Clinical improvements in patients with writer’s cramp (p < 0.05) [301]. | ||

| High frequency over contralateral M1: (10 Hz) | Improvements in muscle tone and stiffness up to 5 weeks (improved MyotonPRO scores (p < 0.01) [300]. | |

| Essential Tremor (ET) | Bilateral 1 Hz over posterior cerebellar cortex | Improvements in tremor severity, drawing impairment, and functional disability (measured by Fahn–Tolosa–Marin scale)(p = 0.006) [308]. |

| Improvements in information processing in the CTC network (p(Δ|y) > 0.909). [308]. | ||

| Bilateral 1 Hz 2 cm below inion | Immediate and temporary (60 min) improvements in tremors (decreased Tremor Clinical Rating Scale score (p < 0.001)) [309]. | |

| 1 Hz over contralateral pre-SMA | Improvements in tremors in treatment groups (dCohen magnitude of 0.49 (moderate effect)) [306]. | |

| Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) | Meta-analysis of 13 studies with 293 participants. | Medium-to-large improvements in cognitive performance (effect size 0.77, p < 0.0001) [318]. |

| Improvements in memory function (p < 0.001) [318]. | |

| Improvements in executive performance (p < 0.001) [318]. | |

| Analysis of 12 studies with 231 patients (focus on RCTs). | Improvements in cognition with subgroup analysis, showing that increasing stimulation sites, number of sessions, and treatment duration resulted in more significant improvements (p < 0.0001). | |

| Meta-analysis of nine studies with 361 patients. | Immediate improvements in cognition lasting more than three months (improved MMSE (p < 0.00001), ADAS-Cog (p < 0.0001). | |

| Greatest improvements in cognition. | |

| Meta-analysis of RCTs. | Improvements in cognitive impairment (p < 0.0006), which further improves with increasing stimulation sites (SMD 0.47, p < 0.0001), number of sessions (>10) (p < 0.003), and higher education levels (≥9 years) (SMD 0.64, p < 0.001). | |

|

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ni, Z.; Chen, R. Excitatory and Inhibitory Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 31, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.T.; Jalinous, R.; Freeston, I.L. Non-Invasive Magnetic Stimulation of Human Motor Cortex. Lancet 1985, 325, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chail, A.; Saini, R.K.; Bhat, P.S.; Srivastava, K.; Chauhan, V. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A review of its evolution and current applications. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2018, 27, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and the human brain. Nature 2000, 406, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, A.T.; Kohler, A.; Bestmann, S.; Linden, D.E.J.; Dechent, P.; Goebel, R.; Baudewig, J. Imaging the brain activity changes underlying impaired visuospatial judgments: Simultaneous FMRI, TMS, and behavioral studies. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2841–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, P.M.; Burke, D.; Chen, R.; Cohen, L.G.; Daskalakis, Z.; Di Iorio, R.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Ferreri, F.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; George, M.S.; et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an I.F.C.N. Committee. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1071–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corp, D.T.; Bereznicki, H.G.K.; Clark, G.M.; Youssef, G.J.; Fried, P.J.; Jannati, A.; Davies, C.B.; Gomes-Osman, J.; Kirkovski, M.; Albein-Urios, N.; et al. Large-scale analysis of interindividual variability in single and paired-pulse TMS data. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2639–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Oliviero, A.; Profice, P.; Insola, A.; Mazzone, P.; Tonali, P.; Rothwell, J.C. Direct recordings of descending volleys after transcranial magnetic and electric motor cortex stimulation in conscious humans. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Suppl. 1999, 51, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Oliviero, A.; Pilato, F.; Saturno, E.; Insola, A.; Mazzone, P.; Tonali, P.A.; Rothwell, J.C. Descending volleys evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain in conscious humans: Effects of coil shape. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Profice, P.; Ranieri, F.; Capone, F.; Dileone, M.; Oliviero, A.; Pilato, F. I-wave origin and modulation. Brain Stimul. 2012, 5, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossini, P.M.; Barker, A.T.; Berardelli, A.; Caramia, M.D.; Caruso, G.; Cracco, R.Q.; Dimitrijević, M.R.; Hallett, M.; Katayama, Y.; Lücking, C.H.; et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1994, 91, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, P.M.; Di Iorio, R.; Bentivoglio, M.; Bertini, G.; Ferreri, F.; Gerloff, C.; Ilmoniemi, R.J.; Miraglia, F.; Nitsche, M.A.; Pestilli, F.; et al. Methods for analysis of brain connectivity: An IFCN-sponsored review. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 1833–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebner, H.R.; Funke, K.; Aberra, A.S.; Antal, A.; Bestmann, S.; Chen, R.; Classen, J.; Davare, M.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Fox, P.T.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain: What is stimulated?—A consensus and critical position paper. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 140, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, M.; Ciocca, M.; Chieffo, R.; Hammond, P.; Neef, A.; Paulus, W.; Rothwell, J.C.; Hannah, R. TMS of primary motor cortex with a biphasic pulse activates two independent sets of excitable neurones. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomjai, W.; Katz, R.; Lackmy-Vallée, A. Basic principles of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and repetitive TMS (rTMS). Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Cros, D.; Curra, A.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Magistris, M.R.; Mills, K.; Rösler, K.M.; Triggs, W.J.; Ugawa, Y.; et al. The clinical diagnostic utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation: Report of an IFCN committee. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 504–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Bella, R.; Benussi, A.; Bologna, M.; Borroni, B.; Capone, F.; Chen, K.-H.S.; Chen, R.; Chistyakov, A.V.; Classen, J.; et al. Diagnostic contribution and therapeutic perspectives of transcranial magnetic stimulation in dementia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2568–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Antal, A.; Bestmann, S.; Bikson, M.; Brewer, C.; Brockmöller, J.; Carpenter, L.L.; Cincotta, M.; Chen, R.; Daskalakis, J.D.; et al. Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 269–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.-C.; Stinear, C.M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in stroke: Ready for clinical practice? J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 31, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Lin, C.S.-Y.; Cheah, B.C.; Murray, J.; Menon, P.; Krishnan, A.V.; Kiernan, M.C. Riluzole exerts central and peripheral modulating effects in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2013, 136, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicak, P.G.; Dokucu, M.E. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of major depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchi, L.; Zalesky, A.; Nott, Z.; Whybird, G.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Breakspear, M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A focus on network mechanisms and state dependence. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 19, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Aleman, A.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Brunelin, J.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Filipović, S.R.; Grefkes, C.; Hasan, A.; Hummel, F.C.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014–2018). Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 474–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A.H. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as Treatment in Multiple Neurologic Conditions. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; André-Obadia, N.; Antal, A.; Ayache, S.S.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Cantello, R.M.; Cincotta, M.; de Carvalho, M.; De Ridder, D.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 2150–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, J.C.; Hallett, M.; Berardelli, A.; Eisen, A.; Rossini, P.; Paulus, W. Magnetic stimulation: Motor evoked potentials. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Suppl. 1999, 52, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen, M.; Laakso, I.; Sumiya, M.; Koyama, S.; Hirata, A.; Tanaka, S. TMS Motor Thresholds Correlate with TDCS Electric Field Strengths in Hand Motor Area. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Tam, A.; Bütefisch, C.; Corwell, B.; Ziemann, U.; Rothwell, J.C.; Cohen, L.G. Intracortical Inhibition and Facilitation in Different Representations of the Human Motor Cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1998, 80, 2870–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, W.G.; Wolf, S.L.; Butler, A.J. Variability of motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation depends on muscle activation. Exp. Brain Res. Exp. Hirnforsch. Exp. Cerebrale 2006, 174, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, D.A.; Ibanez, J.; Rocchi, L.; Rothwell, J. Motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation: Interpreting a simple measure of a complex system. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 2827–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paci, M.; Di Cosmo, G.; Perrucci, M.G.; Ferri, F.; Costantini, M. Cortical silent period reflects individual differences in action stopping performance. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs, W.J.; Macdonell, R.A.L.; Cros, D.; Chiappa, K.H.; Shahani, B.T.; Day, B.J. Motor inhibition and excitation are independent effects of magnetic cortical stimulation. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 32, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiskidis, V.K.; Papagiannopoulos, S.; Sotirakoglou, K.; Kazis, D.A.; Kazis, A.; Mills, K.R. Silent period to transcranial magnetic stimulation: Construction and properties of stimulus–response curves in healthy volunteers. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 163, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Onishi, H.; Sugawara, K.; Kirimoto, H.; Suzuki, M.; Tamaki, H. Modulation of the cortical silent period elicited by single- and paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. BMC Neurosci. 2013, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompetto, C.; Buccolieri, A.; Marinelli, L.; Abbruzzese, G. Differential modulation of motor evoked potential and silent period by activation of intracortical inhibitory circuits. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 1822–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stetkarova, I.; Kofler, M. Differential effect of baclofen on cortical and spinal inhibitory circuits. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compta, Y.; Valls-Solé, J.; Valldeoriola, F.; Kumru, H.; Rumià, J. The silent period of the thenar muscles to contralateral and ipsilateral deep brain stimulation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 2512–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujirai, T.; Caramia, M.D.; Rothwell, J.C.; Day, B.L.; Thompson, P.D.; Ferbert, A.; Wroe, S.; Asselman, P.; Marsden, C.D. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 1993, 471, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Fried, P.J.; Davila-Pérez, P.; Horvath, J.C.; Rotenberg, A.; Pascual-Leone, A. Advanced Neurophysiology Measures. In A Practical Manual for Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; Edwards, D.J., Fried, P.J., Davila-Pérez, P., Horvath, J.C., Rotenberg, A., Pascual-Leone, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.J.; Nakamura, Y.; Bestmann, S.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bostock, H. Two phases of intracortical inhibition revealed by transcranial magnetic threshold tracking. Exp. Brain Res. 2002, 143, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanajima, R.; Furubayashi, T.; Iwata, N.K.; Shiio, Y.; Okabe, S.; Kanazawa, I.; Ugawa, Y. Further evidence to support different mechanisms underlying intracortical inhibition of the motor cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 151, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Howells, J.; Trevillion, L.; Kiernan, M.C. Assessment of cortical excitability using threshold tracking techniques. Muscle Nerve 2006, 33, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.S.-Z.; Samusyte, G.; Pugdahl, K.; Blicher, J.U.; Fuglsang-Frederiksen, A.; Cengiz, B.; Tankisi, H. Test-Retest Reliability of Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition Assessed by Threshold-Tracking and Automated Conventional Techniques. eNeuro 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Rothwell, J.C. Corticospinal activity evoked and modulated by non-invasive stimulation of the intact human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 4115–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Pilato, F.; Dileone, M.; Profice, P.; Ranieri, F.; Ricci, V.; Bria, P.; Tonali, P.A.; Ziemann, U. Segregating two inhibitory circuits in human motor cortex at the level of GABAA receptor subtypes: A TMS study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, U.; Reis, J.; Schwenkreis, P.; Rosanova, M.; Strafella, A.; Badawy, R.; Müller-Dahlhaus, F. TMS and drugs revisited 2014. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1847–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, R.; Pellegrino, G.; Ranieri, F.; Di Pino, G.; Capone, F.; Dileone, M.; Iodice, R.; Ruggiero, L.; Tozza, S.; Uncini, A.; et al. BDNF polymorphism and interhemispheric balance of motor cortex excitability: A preliminary study. J. Neurophysiol. 2022, 127, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsen, A.M.; Haag, A.; Duddek, C.; Balkenhol, K.; Bugiel, H.; Bauer, S.; Mylius, V.; Menzler, K.; Rosenow, F. Test–retest reliability of single and paired pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation parameters in healthy subjects. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 362, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, L.; Maes, C.; Pauwels, L.; Cuypers, K.; Heise, K.-F.; Swinnen, S.P.; Leunissen, I. Age-related alterations in the modulation of intracortical inhibition during stopping of actions. Aging 2019, 11, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garry, M.I.; Thomson, R.H.S. The effect of test TMS intensity on short-interval intracortical inhibition in different excitability states. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 193, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalakis, Z.J.; Paradiso, G.O.; Christensen, B.K.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Gunraj, C.; Chen, R. Exploring the connectivity between the cerebellum and motor cortex in humans. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Cheah, B.C.; Krishnan, A.V.; Burke, D.; Kiernan, M.C. The effects of alterations in conditioning stimulus intensity on short interval intracortical inhibition. Brain Res. 2009, 1273, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, S.; Pugdahl, K.; Nielsen, C.S.; Fuglsang-Frederiksen, A.; Tankisi, H. P221 Comparison of threshold tracking SICI measurements using circular and figure of eight coils. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 131, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmadasa, T.; Matamala, J.M.; Howells, J.; Simon, N.G.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M.C. The effect of coil type and limb dominance in the assessment of lower-limb motor cortex excitability using TMS. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 699, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, P.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S. Cortical excitability varies across different muscles. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massé-Alarie, H.; Cancino, E.E.; Schneider, C.; Hodges, P. Paired-Pulse TMS and Fine-Wire Recordings Reveal Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition and Facilitation of Deep Multifidus Muscle Fascicles. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirota, Y.; Hamada, M.; Terao, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Ohminami, S.; Furubayashi, T.; Nakatani-Enomoto, S.; Ugawa, Y.; Hanajima, R. Influence of short-interval intracortical inhibition on short-interval intracortical facilitation in human primary motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104, 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Garg, R. Facilitatory I Wave Interaction in Proximal Arm and Lower Limb Muscle Representations of the Human Motor Cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2000, 83, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, U.; Tergau, F.; Wassermann, E.M.; Wischer, S.; Hildebrandt, J.; Paulus, W. Demonstration of facilitatory I wave interaction in the human motor cortex by paired transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Physiol. 1998, 511, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, U.; Rothwell, J.C.; Ridding, M.C. Interaction between intracortical inhibition and facilitation in human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 1996, 496, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, C.V.; Murakami, M.; Ziemann, U.; Triesch, J. A Model of TMS-induced I-waves in Motor Cortex. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanajima, R.; Ugawa, Y.; Terao, Y.; Enomoto, H.; Shiio, Y.; Mochizuki, H.; Furubayashi, T.; Uesugi, H.; Iwata, N.K.; Kanazawa, I. Mechanisms of intracortical I-wave facilitation elicited with paired-pulse magnetic stimulation in humans. J. Physiol. 2002, 538, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Stanley Chen, K.-H.; Kiernan, M.C.; Hallett, M.; Benninger, D.H.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Rossini, P.M.; Benussi, A.; Berardelli, A.; Currà, A.; et al. Clinical diagnostic utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurological disorders. Updated report of an IFCN committee. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2023, 150, 131–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Cai, H.; Wu, M.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Lin, T.; Jing, Y.; Yuan, T.; Xu, G.; et al. Short intracortical facilitation associates with motor-inhibitory control. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 407, 113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Bahl, N.; Gunraj, C.A.; Mazzella, F.; Chen, R. Increased motor cortical facilitation and decreased inhibition in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2013, 80, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bos, M.A.J.; Menon, P.; Howells, J.; Geevasinga, N.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S. Physiological Processes Underlying Short Interval Intracortical Facilitation in the Human Motor Cortex. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Lozano, A.M.; Ashby, P. Mechanism of the silent period following transcranial magnetic stimulation. Evidence from epidural recordings. Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 128, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Oliviero, A.; Mazzone, P.; Pilato, F.; Saturno, E.; Insola, A.; Visocchi, M.; Colosimo, C.; Tonali, P.A.; Rothwell, J.C. Direct demonstration of long latency cortico-cortical inhibition in normal subjects and in a patient with vascular parkinsonism. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatih, P.; Kucuker, M.U.; Vande Voort, J.L.; Doruk Camsari, D.; Farzan, F.; Croarkin, P.E. A Systematic Review of Long-Interval Intracortical Inhibition as a Biomarker in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 678088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, T.D.; Garg, R.R.; Chen, R. Interactions between two different inhibitory systems in the human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 2001, 530, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wassermann, E.M.; Caños, M.; Hallett, M. Impaired inhibition in writer’s cramp during voluntary muscle activation. Neurology 1997, 49, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Z.; Charab, S.; Gunraj, C.; Nelson, A.J.; Udupa, K.; Yeh, I.-J.; Chen, R. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Different Current Directions Activates Separate Cortical Circuits. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 105, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemann, U.; Chen, R.; Cohen, L.G.; Hallett, M. Dextromethorphan decreases the excitability of the human motor cortex. Neurology 1998, 51, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Pilato, F.; Oliviero, A.; Dileone, M.; Saturno, E.; Mazzone, P.; Insola, A.; Profice, P.; Ranieri, F.; Capone, F.; et al. Origin of Facilitation of Motor-Evoked Potentials After Paired Magnetic Stimulation: Direct Recording of Epidural Activity in Conscious Humans. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 96, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-L.; Arroyo, D.F.; Carrier, R.; Madonna, E. Is Interhemispheric Inhibition Balanced between the Two Primary Motor Cortices? A Large-scale Analysis. Brain Stimul. Basic Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodulation 2023, 16, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bos, M.A.J.; Higashihara, M.; Geevasinga, N.; Menon, P.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S. Pathophysiological associations of transcallosal dysfunction in ALS. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Leodori, G.; Vial, F.; Zhang, Y.; Avram, A.V.; Pajevic, S.; Basser, P.J.; Hallett, M. Measuring latency distribution of transcallosal fibers using transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Rothwell, J.C.; Oliviero, A.; Profice, P.; Insola, A.; Mazzone, P.; Tonali, P. Intracortical origin of the short latency facilitation produced by pairs of threshold magnetic stimuli applied to human motor cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 129, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlbacher, K.; Brocke, J.; Mechow, J.V.; Brandt, S.A. Effects of GABAA and GABAB agonists on interhemispheric inhibition in man. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, J.; Müller-Dahlhaus, M.; Liu, Y.; Ziemann, U. Inhibitory circuits and the nature of their interactions in the human motor cortex a pharmacological TMS study. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaydin, H.C.; Ataoglu, E.E.; Caglayan, H.Z.B.; Tokgoz, N.; Nazliel, B.; Cengiz, B. Short-latency afferent inhibition remains intact without cortical somatosensory input: Evidence from a patient with isolated thalamic infarct. Brain Stimul. Basic Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodulation 2021, 14, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburin, S.; Fiaschi, A.; Andreoli, A.; Marani, S.; Zanette, G. Sensorimotor integration to cutaneous afferents in humans: The effect of the size of the receptive field. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 167, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.Z.; Asmussen, M.J.; Nelson, A.J. Short-latency afferent inhibition determined by the sensory afferent volley. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 116, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, K.; Takenaka, Y.; Suzuki, T. Effects of sensory afferent input on motor cortex excitability of agonist and antagonist muscles. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 464, 114946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokimura, H.; Ridding, M.C.; Tokimura, Y.; Amassian, V.E.; Rothwell, J.C. Short latency facilitation between pairs of threshold magnetic stimuli applied to human motor cortex. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Mot. Control 1996, 101, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delwaide, P.J.; Olivier, E. Conditioning transcranial cortical stimulation (TCCS) by exteroceptive stimulation in parkinsonian patients. Adv. Neurol. 1990, 53, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nardone, R.; Höller, Y.; Bathke, A.C.; Höller, P.; Lochner, P.; Tezzon, F.; Trinka, E.; Brigo, F. Subjective memory impairment and cholinergic transmission: A TMS study. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, G.; Di Lenola, D.; Abagnale, C.; Ferrandes, F.; Sebastianelli, G.; Casillo, F.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Serrao, M.; Evangelista, M.; Schoenen, J.; et al. Short-latency afferent inhibition and somato-sensory evoked potentials during the migraine cycle: Surrogate markers of a cycling cholinergic thalamo-cortical drive? J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepp, S.L.; Turco, C.V.; Rehsi, R.S.; Nelson, A.J. The distribution and reliability of TMS-evoked short- and long-latency afferent interactions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Corwell, B.; Hallett, M. Modulation of motor cortex excitability by median nerve and digit stimulation. Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 129, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, A.; Molnar, G.F.; Paradiso, G.; Gunraj, C.A.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. Short and long latency afferent inhibition in Parkinson’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 2003, 126, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, C.V.; El-Sayes, J.; Fassett, H.J.; Chen, R.; Nelson, A.J. Modulation of long-latency afferent inhibition by the amplitude of sensory afferent volley. J. Neurophysiol. 2017, 118, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, C.V.; El-Sayes, J.; Locke, M.B.; Chen, R.; Baker, S.; Nelson, A.J. Effects of lorazepam and baclofen on short- and long-latency afferent inhibition. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 5267–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Major, B.P.; Teo, W.-P.; Byrne, L.K.; Enticott, P.G. Assessing cerebellar brain inhibition (CBI) via transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS): A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 86, 176–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Major, B.P.; Teo, W.-P.; Byrne, L.K.; Enticott, P.G. The Impact of Stimulation Intensity and Coil Type on Reliability and Tolerability of Cerebellar Brain Inhibition (CBI) via Dual-Coil TMS. Cerebellum 2018, 17, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugawa, Y.; Uesaka, Y.; Terao, Y.; Hanajima, R.; Kanazawa, I. Magnetic stimulation over the cerebellum in humans. Ann. Neurol. 1995, 37, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werhahn, K.J.; Taylor, J.; Ridding, M.; Meyer, B.U.; Rothwell, J.C. Effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation over the cerebellum on the excitability of human motor cortex. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 101, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, R.M.; Lesage, E.; Miall, R.C. Cerebellar Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: The Role of Coil Geometry and Tissue Depth. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.D.; Chen, R. Suppression of the motor cortex by magnetic stimulation of the cerebellum. Exp. Brain Res. 2001, 140, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, D.A.; Celnik, P.A.; Rothwell, J.C. Cerebellar–Motor Cortex Connectivity: One or Two Different Networks? J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 4230–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, L.V.; Berg, D.; Kordower, J.H.; Shannon, K.M.; Taylor, J.-P.; Cardoso, F.; Goldman, J.G.; Jeon, B.; Meissner, W.G.; Tijssen, M.A.J.; et al. International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Viewpoint on Biological Frameworks of Parkinson’s Disease: Current Status and Future Directions. Mov. Disord. 2024, 39, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglinger, G.U.; Adler, C.H.; Berg, D.; Klein, C.; Outeiro, T.F.; Poewe, W.; Postuma, R.; Stoessl, A.J.; Lang, A.E. A biological classification of Parkinson’s disease: The SynNeurGe research diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Goetz, C.G.; Mestre, T.A.; Sampaio, C.; Adler, C.H.; Berg, D.; Bloem, B.R.; Burn, D.J.; Fitts, M.S.; Gasser, T.; et al. A Statement of the MDS on Biological Definition, Staging, and Classification of Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2024, 39, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridding, M.C.; Rothwell, J.C.; Inzelberg, R. Changes in excitability of motor cortical circuitry in patients with parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1995, 37, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.; Asci, F.; Zampogna, A.; D’Onofrio, V.; Suppa, A.; Fabbrini, G.; Berardelli, A. Long-term changes in short-interval intracortical facilitation modulate motor cortex plasticity and L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, A.; Colella, D.; Giangrosso, M.; Cannavacciuolo, A.; Paparella, G.; Fabbrini, G.; Suppa, A.; Berardelli, A.; Bologna, M. Driving motor cortex oscillations modulates bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2022, 145, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priori, A.; Berardelli, A.; Inghilleri, M.; Accornero, N.; Manfredi, M. Motor cortical inhibition and the dopaminergic system. Pharmacological changes in the silent period after transcranial brain stimulation in normal subjects, patients with Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism. Brain J. Neurol. 1994, 117, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valzania, F.; Strafella, A.P.; Quatrale, R.; Santangelo, M.; Tropeani, A.; Lucchi, D.; Tassinari, C.A.; De Grandis, D. Motor evoked responses to paired cortical magnetic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Mot. Control 1997, 105, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanajima, R.; Terao, Y.; Shirota, Y.; Ohminami, S.; Nakatani-Enomoto, S.; Okabe, S.; Matsumoto, H.; Tsutsumi, R.; Ugawa, Y. Short-interval intracortical inhibition in Parkinson’s disease using anterior-posterior directed currents. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 214, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, C.D.; Gilley, E.A.; Weis-McNulty, A.; Simuni, T. Pathways mediating abnormal intracortical inhibition in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, C.; Dileone, M.; Pagge, C.; Catanzaro, V.; Mata-Marín, D.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; Monje, M.H.G.; Sánchez-Ferro, Á.; Fernández-Rodríguez, B.; Gasca-Salas, C.; et al. Cortical disinhibition in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 3408–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojovic, M.; Kassavetis, P.; Bologna, M.; Pareés, I.; Rubio-Agusti, I.; Beraredelli, A.; Edwards, M.J.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation follow-up study in early Parkinson’s disease: A decline in compensation with disease progression? Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bologna, M.; Guerra, A.; Paparella, G.; Giordo, L.; Alunni Fegatelli, D.; Vestri, A.R.; Rothwell, J.C.; Berardelli, A. Neurophysiological correlates of bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 2432–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammann, C. Essential tremor as a clinical model of cerebello-thalamo-cortical plasticity. Brain Stimul. Basic Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodulation 2023, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, A.; Rona, S.; Inghilleri, M.; Manfredi, M. Cortical inhibition in Parkinson’s disease: A study with paired magnetic stimulation. Brain 1996, 119, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Wagle-Shukla, A.; Gunraj, C.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. Impaired presynaptic inhibition in the motor cortex in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009, 72, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Rothwell, J.C. (Eds.) Cortical Connectivity: Brain Stimulation for Assessing and Modulating Cortical Connectivity and Function; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-32766-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.-K.; Chen, C.-M.; Duann, J.-R.; Ziemann, U.; Chen, J.-C.; Chiou, S.-M.; Tsai, C.-H. Investigation of Motor Cortical Plasticity and Corticospinal Tract Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Patients with Parkinsons Disease and Essential Tremor. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, G.; De Riggi, M.; Cannavacciuolo, A.; Costa, D.; Birreci, D.; Passaretti, M.; Angelini, L.; Colella, D.; Guerra, A.; Berardelli, A.; et al. Interhemispheric imbalance and bradykinesia features in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcae020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacherot, F.; Attarian, S.; Eusebio, A.; Azulay, J.-P. Excitability of the lower-limb area of the motor cortex in Parkinson’s disease. Neurophysiol. Clin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 40, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, F.; Tremblay, L.E. Cortico-motor excitability of the lower limb motor representation: A comparative study in Parkinson’s disease and healthy controls. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantello, R.; Gianelli, M.; Bettucci, D.; Civardi, C.; De Angelis, M.S.; Mutani, R. Parkinson’s disease rigidity: Magnetic motor evoked potentials in a small hand muscle. Neurology 1991, 41, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valls-Solé, J.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Brasil-Neto, J.P.; Cammarota, A.; McShane, L.; Hallett, M. Abnormal facilitation of the response to transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1994, 44, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, F.; Coppi, E.; Chieffo, R.; Straffi, L.; Fichera, M.; Nuara, A.; Gonzalez-Rosa, J.; Martinelli, V.; Comi, G.; Volontè, M.A.; et al. Interhemispheric Balance in Parkinson’s Disease: A Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Study. Brain Stimul. 2013, 6, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Hegde, S.; Vidya, N.; Gothwal, M.; Yadav, R.; Pal, P.K. Cortical excitability changes as a marker of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 422, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bares, M.; Kanovský, P.; Klajblová, H.; Rektor, I. Intracortical inhibition and facilitation are impaired in patients with early Parkinson’s disease: A paired TMS study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2003, 10, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Drouot, X.; Von Raison, F.; Ménard-Lefaucheur, I.; Cesaro, P.; Nguyen, J.-P. Improvement of motor performance and modulation of cortical excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 115, 2530–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bange, M.; Helmich, R.C.G.; Wagle Shukla, A.A.; Deuschl, G.; Muthuraman, M. Non-invasive brain stimulation to modulate neural activity in Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, Y.; Ohminami, S.; Tsutsumi, R.; Terao, Y.; Ugawa, Y.; Tsuji, S.; Hanajima, R. Increased facilitation of the primary motor cortex in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 66, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.; Suppa, A.; D’Onofrio, V.; Di Stasio, F.; Asci, F.; Fabbrini, G.; Berardelli, A. Abnormal cortical facilitation and L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-Y.; Espay, A.J.; Gunraj, C.A.; Pal, P.K.; Cunic, D.I.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. Interhemispheric and ipsilateral connections in Parkinson’s disease: Relation to mirror movements. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, R.; Florio, I.; Lochner, P.; Tezzon, F. Cholinergic cortical circuits in Parkinson’s disease and in progressive supranuclear palsy: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 163, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, L.; Yarnall, A.J.; Baker, M.R.; David, R.V.; Lord, S.; Galna, B.; Burn, D.J. Cholinergic dysfunction contributes to gait disturbance in early Parkinson’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 2012, 135, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosin, E.; Ogliastro, C.; Lagravinese, G.; Bonassi, G.; Mirelman, A.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Abbruzzese, G.; Avanzino, L. Attentional Control of Gait and Falls: Is Cholinergic Dysfunction a Common Substrate in the Elderly and Parkinson’s Disease? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celebi, O.; Temuçin, Ç.M.; Elibol, B.; Saka, E. Short latency afferent inhibition in Parkinson’s disease patients with dementia. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, R.; Bergmann, J.; Brigo, F.; Christova, M.; Kunz, A.; Seidl, M.; Tezzon, F.; Trinka, E.; Golaszewski, S. Functional evaluation of central cholinergic circuits in patients with Parkinson’s disease and REM sleep behavior disorder: A TMS study. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarnall, A.J.; Rochester, L.; Baker, M.R.; David, R.; Khoo, T.K.; Duncan, G.W.; Galna, B.; Burn, D.J. Short latency afferent inhibition: A biomarker for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease? Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1285–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picillo, M.; Dubbioso, R.; Iodice, R.; Iavarone, A.; Pisciotta, C.; Spina, E.; Santoro, L.; Barone, P.; Amboni, M.; Manganelli, F. Short-latency afferent inhibition in patients with Parkinson’s disease and freezing of gait. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, T.L.; Stratton, P.G.; Coyne, T.J.; Cook, R.; Silberstein, P.; Silburn, P.A.; Windels, F.; Sah, P. Imagined gait modulates neuronal network dynamics in the human pedunculopontine nucleus. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnen, N.I.; Frey, K.A.; Studenski, S.; Kotagal, V.; Koeppe, R.A.; Constantine, G.M.; Scott, P.J.H.; Albin, R.L.; Müller, M.L.T.M. Extra-nigral pathological conditions are common in Parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait: An in vivo positron emission tomography study. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pana, A.; Saggu, B.M. Dystonia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448144/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Steeves, T.D.; Day, L.; Dykeman, J.; Jette, N.; Pringsheim, T. The prevalence of primary dystonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, N. Contemporary functional neuroanatomy and pathophysiology of dystonia. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojovic, M.; Pareés, I.; Kassavetis, P.; Palomar, F.J.; Mir, P.; Teo, J.T.; Cordivari, C.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P.; Edwards, M.J. Secondary and primary dystonia: Pathophysiological differences. Brain 2013, 136, 2038–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartarone, A.; Rizzo, V.; Terranova, C.; Morgante, F.; Schneider, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Girlanda, P.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. Abnormal sensorimotor plasticity in organic but not in psychogenic dystonia. Brain 2009, 132, 2871–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCambridge, A.B.; Bradnam, L.V. Cortical neurophysiology of primary isolated dystonia and non-dystonic adults: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 1300–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.; Richardson, S.P.; Shamim, E.A.; Dang, N.; Schubert, M.; Hallett, M. Short Intracortical and Surround Inhibition Are Selectively Reduced during Movement Initiation in Focal Hand Dystonia. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 10363–10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, M.; Paparella, G.; Fabbrini, A.; Leodori, G.; Rocchi, L.; Hallett, M.; Berardelli, A. Effects of cerebellar theta-burst stimulation on arm and neck movement kinematics in patients with focal dystonia. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 3472–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcacchia, P.; Álvarez de Toledo, P.; Rodríguez-Baena, A.; Martín-Rodríguez, J.F.; Palomar, F.J.; Vargas-González, L.; Jesús, S.; Koch, G.; Mir, P. Abnormal cerebellar connectivity and plasticity in isolated cervical dystonia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espay, A.J.; Morgante, F.; Purzner, J.; Gunraj, C.A.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. Cortical and spinal abnormalities in psychogenic dystonia. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 59, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D. Elevated threshold for intracortical inhibition in focal hand dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Thompson, P.D.; Ridding, M.C. The effect of cutaneous input on intracortical inhibition in focal task-specific dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighina, F.; Romano, M.; Giglia, G.; Saia, V.; Puma, A.; Giglia, F.; Fierro, B. Effects of cerebellar TMS on motor cortex of patients with focal dystonia: A preliminary report. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 192, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilio, F.; Currà, A.; Inghilleri, M.; Lorenzano, C.; Suppa, A.; Manfredi, M.; Berardelli, A. Abnormalities of motor cortex excitability preceding movement in patients with dystonia. Brain J. Neurol. 2003, 126, 1745–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-Z.; Trender-Gerhard, I.; Edwards, M.J.; Mir, P.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P. Motor system inhibition in dopa-responsive dystonia and its modulation by treatment. Neurology 2006, 66, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.J.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Wood, N.W.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P. Different patterns of electrophysiological deficits in manifesting and non-manifesting carriers of the DYT1 gene mutation. Brain J. Neurol. 2003, 126, 2074–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadio, S.; Houdayer, E.; Bianchi, F.; Tesfaghebriel Tekle, H.; Urban, I.P.; Butera, C.; Guerriero, R.; Cursi, M.; Leocani, L.; Comi, G.; et al. Sensory tricks and brain excitability in cervical dystonia: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganos, C.; Ferrè, E.R.; Marotta, A.; Kassavetis, P.; Rothwell, J.; Bhatia, K.P.; Haggard, P. Cortical inhibitory function in cervical dystonia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2018, 129, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kägi, G.; Ruge, D.; Brugger, F.; Katschnig, P.; Sauter, R.; Fiorio, M.; Tinazzi, M.; Rothwell, J.; Bhatia, K.P. Endophenotyping in idiopathic adult onset cervical dystonia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rona, S.; Berardelli, A.; Vacca, L.; Inghilleri, M.; Manfredi, M. Alterations of motor cortical inhibition in patients with dystonia. Mov. Disord. 1998, 13, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubsch, C.; Roze, E.; Popa, T.; Russo, M.; Balachandran, A.; Pradeep, S.; Mueller, F.; Brochard, V.; Quartarone, A.; Degos, B.; et al. Defective cerebellar control of cortical plasticity in writer’s cramp. Brain 2013, 136, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samargia, S.; Schmidt, R.; Kimberley, T.J. Cortical Silent Period Reveals Differences Between Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia and Muscle Tension Dysphonia. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2016, 30, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovský, P.; Bares, M.; Streitová, H.; Klajblová, H.; Daniel, P.; Rektor, I. Abnormalities of cortical excitability and cortical inhibition in cervical dystonia Evidence from somatosensory evoked potentials and paired transcranial magnetic stimulation recordings. J. Neurol. 2003, 250, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilio, F.; Currà, A.; Lorenzano, C.; Modugno, N.; Manfredi, M.; Berardelli, A. Effects of botulinum toxin type A on intracortical inhibition in patients with dystonia. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 48, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanajima, R.; Okabe, S.; Terao, Y.; Furubayashi, T.; Arai, N.; Inomata-Terada, S.; Hamada, M.; Yugeta, A.; Ugawa, Y. Difference in intracortical inhibition of the motor cortex between cortical myoclonus and focal hand dystonia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 1400–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, S.; Russmann, H.; Shamim, E.; Lamy, J.-C.; Hallett, M. Plasticity of cortical inhibition in dystonia is impaired after motor learning and Paired-Associative Stimulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyadjian, A.; Tyč, F.; Allam, N.; Brasil-Neto, J.P. Writer’s cramp: Cortical excitability in tasks involving proximo-distal coordination. Acta Physiol. 2011, 203, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D. Task-dependent modulation of silent period duration in focal hand dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinazzi, M.; Farina, S.; Edwards, M.; Moretto, G.; Restivo, D.; Fiaschi, A.; Berardelli, A. Task-specific impairment of motor cortical excitation and inhibition in patients with writer’s cramp. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 378, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, S.P. Enhanced dorsal premotor-motor inhibition in cervical dystonia. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, N.; de Oliva Fonte-Boa, P.M.; Tomaz, C.A.B.; Brasil-Neto, J.P. Lack of Effect of Botulinum Toxin on Cortical Excitability in Patients with Cranial Dystonia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2005, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, L.; von Alt-Stutterheim, K.; Röricht, S.; Meyer, B.U. Abnormal postexcitatory and interhemispheric motor cortex inhibition in writer’s cramp. J. Neurol. 2001, 248, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J.; Hoque, T.; Gunraj, C.; Ni, Z.; Chen, R. Impaired interhemispheric inhibition in writer’s cramp. Neurology 2010, 75, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S.; Shamim, E.A.; Pirio Richardson, S.; Schubert, M.; Hallett, M. Inter-hemispheric inhibition is impaired in mirror dystonia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 1634–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, V.; Dickler, M.; Michaud, M.; Meunier, S.; Simonetta-Moreau, M. Does abnormal interhemispheric inhibition play a role in mirror dystonia? Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumer, T.; Schmidt, A.; Heldmann, M.; Landwehr, M.; Simmer, A.; Tönniges, D.; Münte, T.; Lohmann, K.; Altenmüller, E.; Klein, C.; et al. Abnormal interhemispheric inhibition in musician’s dystonia—Trait or state? Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 25, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzese, G.; Marchese, R.; Buccolieri, A.; Gasparetto, B.; Trompetto, C. Abnormalities of sensorimotor integration in focal dystonia: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Brain J. Neurol. 2001, 124, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirio Richardson, S.; Bliem, B.; Voller, B.; Dang, N.; Hallett, M. Long-latency afferent inhibition during phasic finger movement in focal hand dystonia. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 193, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, K.R.; Ruge, D.; Ilić, T.V.; Ziemann, U. Short latency afferent inhibition and facilitation in patients with writer’s cramp. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2005, 20, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.P.; Bliem, B.; Lomarev, M.; Shamim, E.; Dang, N.; Hallett, M. Changes in short afferent inhibition during phasic movement in focal dystonia. Muscle Nerve 2008, 37, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, R.; Bhatia, K.; Graybiel, A.M. Pathogenesis of dystonia: Is it of cerebellar or basal ganglia origin? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Porcacchia, P.; Ponzo, V.; Carrillo, F.; Cáceres-Redondo, M.T.; Brusa, L.; Desiato, M.T.; Arciprete, F.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Pisani, A.; et al. Effects of Two Weeks of Cerebellar Theta Burst Stimulation in Cervical Dystonia Patients. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondergaard, R.E.; Strzalkowski, N.D.J.; Gan, L.S.; Jasaui, Y.; Furtado, S.; Pringsheim, T.M.; Sarna, J.R.; Avanzino, L.; Kiss, Z.H.T.; Martino, D. Cerebellar Brain Inhibition Is Associated with the Severity of Cervical Dystonia. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. Publ. Am. Electroencephalogr. Soc. 2023, 40, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.D.; Ferreira, J.J. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2010, 25, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfati, N.; Shoeibi, A.; Abdollahian, E.; Ahmadi, H.; Hoseini, A.; Akhlaghi, S.; Vakili, V.; Foroughipour, M.; Rezaeitalab, F.; Farzadfard, M.-T.; et al. Cerebellar repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for essential tremor: A double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover, add-on clinical trial. Brain Stimul. Basic Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodulation 2020, 13, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raethjen, J.; Deuschl, G. The oscillating central network of Essential tremor. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanajima, R.; Tsutsumi, R.; Shirota, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Tanaka, N.; Ugawa, Y. Cerebellar dysfunction in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2016, 31, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.D.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. The cerebellothalamocortical pathway in essential tremor. Neurology 2003, 60, 1985–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.-L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Lu, C.-S.; Chen, R.-S. Reduced cortical plasticity and GABAergic modulation in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birreci, D.; Angelini, L.; Paparella, G.; Costa, D.; Cannavacciuolo, A.; Passaretti, M.; De Riggi, M.; Aloisio, S.; Colella, D.; Guerra, A.; et al. Pathophysiological Role of Primary Motor Cortex in Essential Tremor. Mov. Disord. 2025, 40, 1648–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, S.; Berardelli, A.; Pedace, F.; Inghilleri, M.; Giovannelli, M.; Manfredi, M. Cortical excitability in patients with essential tremor. Muscle Nerve 1998, 21, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, G.F.; Sailer, A.; Gunraj, C.A.; Cunic, D.I.; Lang, A.E.; Lozano, A.M.; Moro, E.; Chen, R. Changes in cortical excitability with thalamic deep brain stimulation. Neurology 2005, 64, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L.; Batla, A.; Berardelli, A.; Rothwell, J.C.; Bhatia, K.P. The Signature of Primary Writing Tremor Is Dystonic. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, G.; Bhatia, M.; Pandey, R.M.; Behari, M. Cortical silent period in essential tremor. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 43, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Khedr, E.M.; El Fawal, B.; Abdelwarith, A.; Nasreldein, A.; Rothwell, J.C.; Saber, M. TMS excitability study in essential tremor: Absence of gabaergic changes assessed by silent period recordings. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2019, 49, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellriegel, H.; Schulz, E.M.; Siebner, H.R.; Deuschl, G.; Raethjen, J.H. Continuous theta-burst stimulation of the primary motor cortex in essential tremor. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelnik Žakelj, K.; Prezelj, N.; Gregorič Kramberger, M.; Kojović, M. Mechanisms of tremor-modulating effects of primidone and propranolol in essential tremor. Park. Relat. Disord. 2024, 128, 107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Oliviero, A.; Pilato, F.; Saturno, E.; Dileone, M.; Marra, C.; Daniele, A.; Ghirlanda, S.; Gainotti, G.; Tonali, P.A. Motor cortex hyperexcitability to transcranial magnetic stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, F.; Martorana, A.; Ponzo, V.; Bonnì, S.; D’Angelo, E.; Caltagirone, C.; Koch, G. Cerebellar theta burst stimulation modulates short latency afferent inhibition in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagona, G.; Ferri, R.; Pennisi, G.; Carnemolla, A.; Maci, T.; Domina, E.; Maertens de Noordhout, A.; Bella, R. Motor cortex excitability in Alzheimer’s disease and in subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 362, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, E.M.; Ahmed, M.A.; Darwish, E.S.; Ali, A.M. The relationship between motor cortex excitability and severity of Alzheimer’s disease: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neurophysiol. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 41, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; Mori, F.; Esposito, Z.; Kusayanagi, H.; Monteleone, F.; Codecà, C.; Sancesario, G.; Bernardi, G.; Koch, G. Dopamine Modulates Cholinergic Cortical Excitability in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Ponzo, V.; Pellicciari, M.C.; Bonnì, S.; Picazio, S.; Mercuri, N.B.; Caltagirone, C.; Martorana, A.; Koch, G. Transcranial magnetic stimulation predicts cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Han, L.; Zhou, Y. Cortical function in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Transl. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terranova, C.; Sant’Angelo, A.; Morgante, F.; Rizzo, V.; Allegra, R.; Arena, M.G.; Ricciardi, L.; Ghilardi, M.F.; Girlanda, P.; Quartarone, A. Impairment of sensory-motor plasticity in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Stimul. 2013, 6, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirinzi, T.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Sancesario, G.M.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Ponzo, V.; Pisani, A.; Mercuri, N.B.; Koch, G.; Martorana, A. Amyloid-Mediated Cholinergic Dysfunction in Motor Impairment Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyn, M.; Teipel, S.J.; Oltmann, I.; Bauer, A.; Thome, J.; Großmann, A.; Hauenstein, K.; Höppner, J. Structural and functional cortical disconnection in Alzheimer’s disease: A combined study using diffusion tensor imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2013, 212, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Pilato, F.; Dileone, M.; Saturno, E.; Profice, P.; Marra, C.; Daniele, A.; Ranieri, F.; Quaranta, D.; Gainotti, G.; et al. Functional evaluation of cerebral cortex in dementia with Lewy bodies. NeuroImage 2007, 37, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagona, G.; Bella, R.; Ferri, R.; Carnemolla, A.; Pappalardo, A.; Costanzo, E.; Pennisi, G. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in Alzheimer disease: Motor cortex excitability and cognitive severity. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 314, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.-K.; Atkinson, N.; Seligson, E.; Pascual-Leone, A. Differential Pharmacological Effects on Brain Reactivity and Plasticity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorana, A.; Stefani, A.; Palmieri, M.G.; Esposito, Z.; Bernardi, G.; Sancesario, G.; Pierantozzi, M. l-dopa modulates motor cortex excitability in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Neural Transm. 2008, 115, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeppner, J.; Wegrzyn, M.; Thome, J.; Bauer, A.; Oltmann, I.; Buchmann, J.; Teipel, S. Intra- and inter-cortical motor excitability in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2012, 119, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantozzi, M.; Panella, M.; Palmieri, M.G.; Koch, G.; Giordano, A.; Marciani, M.G.; Bernardi, G.; Stanzione, P.; Stefani, A. Different TMS patterns of intracortical inhibition in early onset Alzheimer dementia and frontotemporal dementia. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 115, 2410–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepert, J.; Bär, K.J.; Meske, U.; Weiller, C. Motor cortex disinhibition in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberici, A.; Bonato, C.; Calabria, M.; Agosti, C.; Zanetti, O.; Miniussi, C.; Padovani, A.; Rossini, P.M.; Borroni, B. The contribution of TMS to frontotemporal dementia variants. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2008, 118, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Esposito, Z.; Lo Giudice, T.; Bernardi, G.; Caltagirone, C.; Koch, G. Dopamine D2-agonist Rotigotine effects on cortical excitability and central cholinergic transmission in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benussi, A.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Dell’Era, V.; Cosseddu, M.; Alberici, A.; Caratozzolo, S.; Cotelli, M.S.; Micheli, A.; Rozzini, L.; Depari, A.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation distinguishes Alzheimer disease from frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2017, 89, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Pilato, F.; Dileone, M.; Profice, P.; Marra, C.; Ranieri, F.; Quaranta, D.; Gainotti, G.; Tonali, P.A. In vivo functional evaluation of central cholinergic circuits in vascular dementia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 2494–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, R.; Bergmann, J.; Kronbichler, M.; Kunz, A.; Klein, S.; Caleri, F.; Tezzon, F.; Ladurner, G.; Golaszewski, S. Abnormal short latency afferent inhibition in early Alzheimer’s disease: A transcranial magnetic demonstration. J. Neural Transm. 2008, 115, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, Y.; Nishida, H.; Nakajima, S.; Tsugawa, S.; Morita, S.; Yoshida, K.; Tarumi, R.; Ogyu, K.; Wada, M.; Kurose, S.; et al. Neurophysiological biomarkers using transcranial magnetic stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 121, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.; Sundman, M.; Ton That, V.; Green, J.; Trapani, C. Cortical excitability and plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of transcranial magnetic stimulation studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, V.; Oliviero, A.; Tonali, P.A.; Marra, C.; Daniele, A.; Profice, P.; Saturno, E.; Pilato, F.; Masullo, C.; Rothwell, J.C. Noninvasive in vivo assessment of cholinergic cortical circuits in AD using transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology 2002, 59, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inghilleri, M.; Conte, A.; Frasca, V.; Scaldaferri, N.; Gilio, F.; Santini, M.; Fabbrini, G.; Prencipe, M.; Berardelli, A. Altered response to rTMS in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebbastoni, A.; Gilio, F.; D’Antonio, F.; Cambieri, C.; Ceccanti, M.; de Lena, C.; Inghilleri, M. Chronic treatment with rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A study on primary motor cortex excitability tested by 5 Hz-repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issac, T.G.; Chandra, S.R.; Nagaraju, B.C. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with early cortical dementia: A pilot study. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2013, 16, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benussi, A.; Grassi, M.; Palluzzi, F.; Koch, G.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Nardone, R.; Cantoni, V.; Dell’Era, V.; Premi, E.; Martorana, A.; et al. Classification Accuracy of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Dementias. Ann. Neurol. 2020, 87, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazarán, J.; Prieto, J.; Cruz, I.; Esteban, A. Cortical excitability in very mild Alzheimer’s disease: A long-term follow-up study. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 2078–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Del Olmo, M.F.; Bonní, S.; Ponzo, V.; Caltagirone, C.; Bozzali, M.; Martorana, A. Reversal of LTP-Like Cortical Plasticity in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients with Tau-Related Faster Clinical Progression. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2016, 50, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, F.; Motta, C.; Bonnì, S.; Mercuri, N.B.; Caltagirone, C.; Martorana, A.; Koch, G. LTP-like cortical plasticity is associated with verbal memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, R.; Cantone, M.; Lanza, G.; Ferri, R.; Vinciguerra, L.; Puglisi, V.; Pennisi, M.; Ricceri, R.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Pennisi, G. Cholinergic circuitry functioning in patients with vascular cognitive impairment—No dementia. Brain Stimul. 2016, 9, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.T.; Rocchi, L.; Hammond, P.; Hardy, C.J.D.; Warren, J.D.; Ridha, B.H.; Rothwell, J.; Rossor, M.N. Effect of donepezil on transcranial magnetic stimulation parameters in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, F.G.; Saka, E.; Elibol, B.; Temucin, C.M. Modulation of Cerebellar-Cortical Connections in Multiple System Atrophy Type C by Cerebellar Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2018, 21, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, R.; Höller, Y.; Thomschewski, A.; Kunz, A.B.; Lochner, P.; Golaszewski, S.; Trinka, E.; Brigo, F. Dopamine differently modulates central cholinergic circuits in patients with Alzheimer disease and CADASIL. J. Neural Transm. 2014, 121, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Schoo, C. Mild Cognitive Impairment. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK599514/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Roberts, R.O.; Knopman, D.S.; Mielke, M.M.; Cha, R.H.; Pankratz, V.S.; Christianson, T.J.H.; Geda, Y.E.; Boeve, B.F.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; et al. Higher risk of progression to dementia in mild cognitive impairment cases who revert to normal. Neurology 2014, 82, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benussi, A.; Grassi, M.; Palluzzi, F.; Cantoni, V.; Cotelli, M.S.; Premi, E.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Pellicciari, M.C.; Ranieri, F.; Musumeci, G.; et al. Classification accuracy of TMS for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, R.; Bergmann, J.; Christova, M.; Caleri, F.; Tezzon, F.; Ladurner, G.; Trinka, E.; Golaszewski, S. Short latency afferent inhibition differs among the subtypes of mild cognitive impairment. J. Neural Transm. 2012, 119, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, A.; Benussi, A.; Cantoni, V.; Dell’Era, V.; Cotelli, M.S.; Caratozzolo, S.; Turrone, R.; Rozzini, L.; Alberici, A.; Altomare, D.; et al. Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 65, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, K.; Murakami, T.; Nakashima, K. Short latency afferent inhibition is not impaired in mild cognitive impairment. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, R.; Hanajima, R.; Hamada, M.; Shirota, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Terao, Y.; Ohminami, S.; Yamakawa, Y.; Shimada, H.; Tsuji, S.; et al. Reduced interhemispheric inhibition in mild cognitive impairment. Exp. Brain Res. 2012, 218, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Lahr, J.; Minkova, L.; Lauer, E.; Grothe, M.J.; Teipel, S.; Köstering, L.; Kaller, C.P.; Heimbach, B.; Hüll, M.; et al. Contribution of the Cholinergic System to Verbal Memory Performance in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2016, 53, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahr, J.; Peter, J.; Minkova, L.; Lauer, E.; Reis, J.; Heimbach, B.; Hüll, M.; Normann, C.; Nissen, C.; Klöppel, S. No difference in paired associative stimulation induced cortical neuroplasticity between patients with mild cognitive impairment and elderly controls. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padovani, A.; Benussi, A.; Cotelli, M.S.; Ferrari, C.; Cantoni, V.; Dell’Era, V.; Turrone, R.; Paghera, B.; Borroni, B. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and amyloid markers in mild cognitive impairment: Impact on diagnostic confidence and diagnostic accuracy. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivanandy, P.; Leey, T.C.; Xiang, T.C.; Ling, T.C.; Wey Han, S.A.; Semilan, S.L.A.; Hong, P.K. Systematic Review on Parkinson’s Disease Medications, Emphasizing on Three Recently Approved Drugs to Control Parkinson’s Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo-Moreno, T.; García-Morales, V.; Suleiman-Martos, S.; Rivas-Domínguez, A.; Mohamed-Mohamed, H.; Ramos-Rodríguez, J.J.; Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; González-Acedo, A. Current Treatments and New, Tentative Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radder, D.L.M.; Lígia Silva de Lima, A.; Domingos, J.; Keus, S.H.J.; van Nimwegen, M.; Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M. Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Present Treatment Modalities. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.C.; Shill, H.; Ponce, F.; Aslam, S. Deep brain stimulation in PD: Risk of complications, morbidity, and hospitalizations: A systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1258190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Usman, O.; Ur Rehman, H.; Jhaveri, S.; Avanthika, C.; Hussain, K.; Islam, H.; I S K, S. Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2022, 14, e28760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, J.E.; Stern, M.B. Medication Non-adherence in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2013, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Zhu, P.; Li, Z.; Holmes, C.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, H.; Bao, X.; Xie, J.-Y. Efficacy of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Over the Supplementary Motor Area on Motor Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 104, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrión, O. Basic mechanisms of rTMS: Implications in Parkinson’s disease. Int. Arch. Med. 2008, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamusuo, S.; Hirvonen, J.; Lindholm, P.; Martikainen, I.K.; Hagelberg, N.; Parkkola, R.; Taiminen, T.; Hietala, J.; Helin, S.; Virtanen, A.; et al. Neurotransmitters behind pain relief with transcranial magnetic stimulation—Positron emission tomography evidence for release of endogenous opioids. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumond Marra, H.L.; Myczkowski, M.L.; Maia Memória, C.; Arnaut, D.; Leite Ribeiro, P.; Sardinha Mansur, C.G.; Lancelote Alberto, R.; Boura Bellini, B.; Alves Fernandes da Silva, A.; Tortella, G.; et al. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Address Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Study. Behav. Neurol. 2015, 2015, 287843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarrawi, J.; Peyron, R.; Mertens, P.; Costes, N.; Magnin, M.; Sindou, M.; Laurent, B.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Brain opioid receptor density predicts motor cortex stimulation efficacy for chronic pain. Pain 2013, 154, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausmann, A.; Weis, C.; Marksteiner, J.; Hinterhuber, H.; Humpel, C. Chronic repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances c-fos in the parietal cortex and hippocampus. Mol. Brain Res. 2000, 76, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervyakov, A.V.; Chernyavsky, A.Y.; Sinitsyn, D.O.; Piradov, M.A. Possible Mechanisms Underlying the Therapeutic Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftanas, L.I.; Gevorgyan, M.M.; Zhanaeva, S.Y.; Dzemidovich, S.S.; Kulikova, K.I.; Al’perina, E.L.; Danilenko, K.V.; Idova, G.V. Therapeutic Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) on Neuroinflammation and Neuroplasticity in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Placebo-Controlled Study. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 165, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, N.; Armony, J.L.; Soto, J.; Trejo, D.; Alegría, M.A.; Drucker-Colín, R. Effects of rTMS on Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal fMRI study. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.S.; Strafella, A.P. rTMS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex modulates dopamine release in the ipsilateral anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strafella, A.P.; Paus, T.; Fraraccio, M.; Dagher, A. Striatal dopamine release induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain 2003, 126, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebner, H.R.; Rossmeier, C.; Mentschel, C.; Peinemann, A.; Conrad, B. Short-term motor improvement after sub-threshold 5-Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor hand area in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000, 178, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khedr, E.M.; Farweez, H.M.; Islam, H. Therapeutic effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function in Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2003, 10, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.C. Techniques and mechanisms of action of transcranial stimulation of the human motor cortex. J. Neurosci. Methods 1997, 74, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.; Hamid, U.; Jamil, A.; Zainab, A.Z.; Yousuf, T.; Habib, S.; Tariq, S.M.; Ali, F. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Therapeutic Option for Neurologic and Psychiatric Illnesses. Cureus 2018, 10, e3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre, A.; Rocchi, L.; Berardelli, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Rothwell, J.C. The use of transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for movement disorders: A critical review. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemam, A.I.; Eltantawi, M.A. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Treatment of Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Res. 2019, 9, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G. rTMS effects on levodopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease patients: Searching for effective cortical targets. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2010, 28, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, E.F.; Fregni, F.; Martins Maia, F.; Boggio, P.S.; Luis Myczkowski, M.; Coracini, K.; Lopes Vieira, A.; Melo, L.M.; Sato, J.R.; Antonio Marcolin, M.; et al. rTMS treatment for depression in Parkinson’s disease increases BOLD responses in the left prefrontal cortex. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brys, M.; Fox, M.D.; Agarwal, S.; Biagioni, M.; Dacpano, G.; Kumar, P.; Pirraglia, E.; Chen, R.; Wu, A.; Fernandez, H.; et al. Multifocal repetitive TMS for motor and mood symptoms of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2016, 87, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.; Ugawa, Y.; Tsuji, S. High-frequency rTMS over the supplementary motor area for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Hamada, M.; Enomoto, H.; Ugawa, Y. For the Research Committee on rTMS Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease Supplementary motor area stimulation for Parkinson disease. Neurology 2013, 80, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.R.; Anschel, D.; Sparing, R.; Gangitano, M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Subthreshold low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation selectively decreases facilitation in the motor cortex. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangitano, M.; Valero-Cabré, A.; Tormos, J.M.; Mottaghy, F.M.; Romero, J.R.; Pascual-Leone, A. Modulation of input-output curves by low and high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]