Computational Advances in Taste Perception: From Ion Channels and Taste Receptors to Neural Coding

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To establish a biologically grounded transduction layer by implementing biomorphic taste cells with modality-specific receptor dynamics (T1R/T2R for sweet and bitter; ENaC for salty; H+ channels for sour) and Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz ion-current calculations, with the goal of preserving ionic realism required for end-to-end simulation of taste transduction and neural coding.

- To construct mechanistic synapses by modeling glutamate release with alpha-function kinetics and phosphorylation-dependent AMPA receptor trafficking coupled to spike-timing-dependent plasticity, with the goal of enabling adaptive, temporally precise coding at the synaptic level.

- To develop a multiscale learning framework that jointly optimizes temporal spike synchrony and combinatorial population patterns, with the goal of producing distinct, sparse, and reproducible spiking fingerprints for pure and mixed tastants and supporting efficient large-scale simulation via Hodgkin–Huxley and Izhikevich single-cell dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Environment

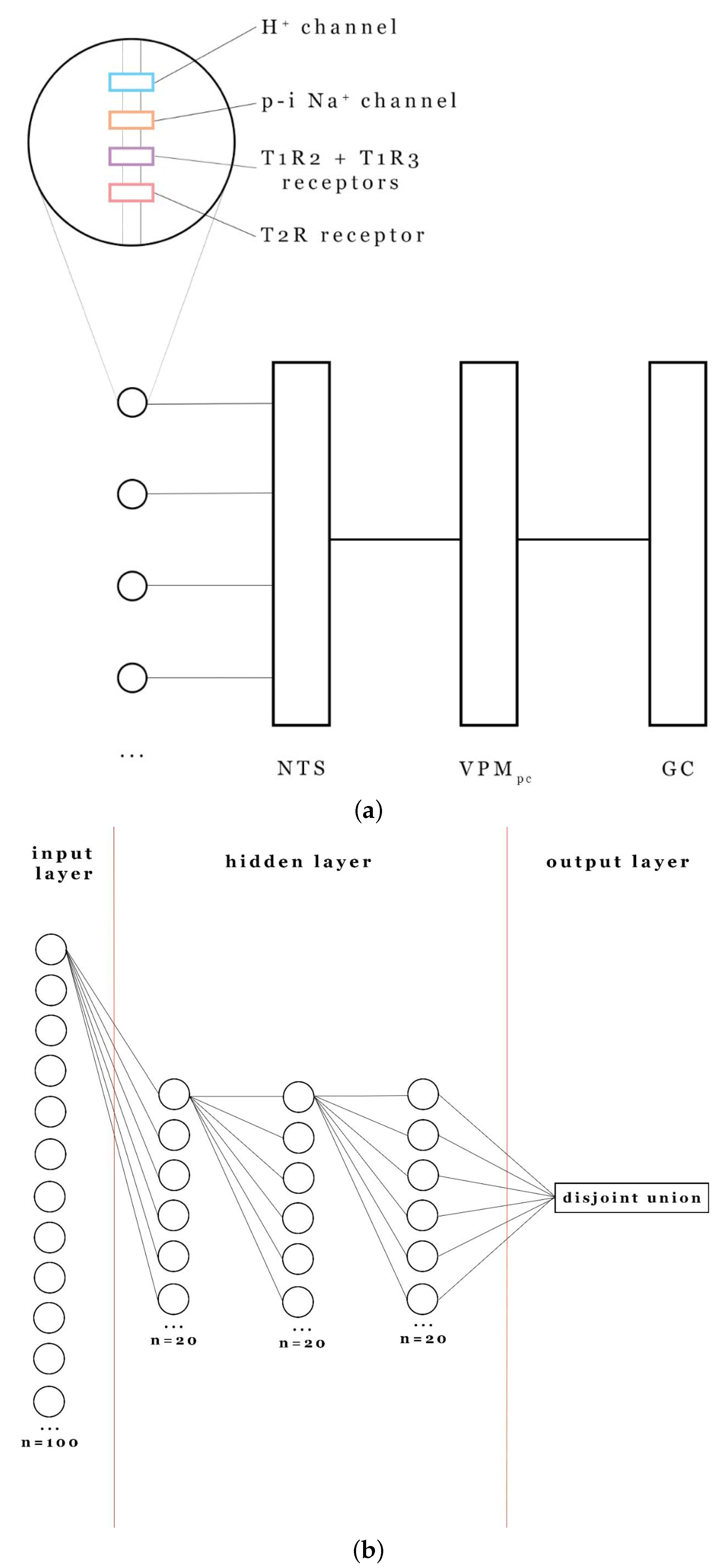

2.2. Modeling of Individual Taste Cells

- Salty—Salt taste engages at least two partially dissociable transduction branches that differ by concentration range, pharmacology, and behavioral valence. Appetitive, amiloride-sensitive responses at low–moderate NaCl are mediated by epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) on taste-bud cells associated with the Type I lineage, where Na+ influx along the electrochemical gradient depolarizes the cell and promotes ATP release to gustatory afferents [1,10]. Aversive, amiloride-insensitive responses to high salt reflect anion-dependent mechanisms and additional ion-channel pathways (including inhibition of K+ conductances and TRP-like contributions), with cellular participation extending beyond the ENaC pathway and involving presynaptic Type III circuitry; these routes can vary across anions and produce distinct molecular dynamics and behavioral outcomes [1]. Model interpretation: in this work, the salty pathway is instantiated specifically for sodium chloride as an ENaC-like, non-voltage-gated Na+ conductance (GHK-driven), capturing appetitive and mid-range NaCl responses; amiloride pharmacology is not explicitly simulated, anion-specific high-salt (amiloride-insensitive) mechanisms are omitted, and receptor-level contributions reported for certain organic or chloride-containing tastants are outside the present scope [1,10].

- Sour—detection primarily in Type III presynaptic cells via proton-sensitive mechanisms that depolarize the cell (including H+ conductance and inhibition of K+ channels), followed by classical synaptic transmission (serotonin, GABA) to afferents [11,12]. Model interpretation: implemented as a non-voltage-gated H+ (proton) depolarizing pathway (GHK-driven current) with reduced channel specificity, preserving the net H+-dependent depolarization and synaptic output [11,12].

- Umami as an independent taste modality is absent in our model. From a computational neuroscience perspective, umami shares the same metabotropic transduction mechanism as sweet and bitter tastes [13]. Specifically, umami receptors (T1R1/T1R3 heterodimers) utilize G-protein coupled signaling cascades and intracellular IP3/Ca2+ pathways, described by the same Hill-type kinetics (Equations (3) and (4)) as sweet (T1R2/T1R3) and bitter (T2R) receptors. At the level of our model’s equations, these three modalities differ only in the ligand concentration and binding affinity , but the functional form of the transduction current is identical. Moreover, as noted in recent comprehensive reviews [14,15], umami compounds constitute a significantly smaller chemical space compared to sweet or bitter tastants, with most databases containing fewer than 800 umami molecules [16], predominantly short peptides (glutamate, nucleotides). This narrow chemical domain would not provide sufficient diversity to test the network’s plasticity mechanisms, which were optimized for discriminating broader taste categories. Therefore, we focused our validation on the three major metabotropic classes (sweet, bitter) plus the ionotropic modalities (salty, sour), reserving umami integration for future work when receptor-specific affinity data become more widely available.

2.2.1. Ionic Current Calculations

- Electrodiffusion currents (Salty/Sour). The current through Na+ and H+ channels was computed using the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz (GHK) equation for the reversal potential () of each ion [17]:where and are extracellular and intracellular ion concentrations, respectively, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is ion valence, and F is Faraday’s constant.The resultant current () was calculated as follows:where is the channel conductance and is the membrane potential.

- Metabotropic currents (Sweet/Bitter). The activation kinetics of metabotropic receptors (T1R2+T1R3, T2R) were modeled using Hill equations, where the fraction of open channels (O) depended on tastant concentration () and the half-maximal activation constant (), derived from experimentally reported minimal detectable concentrations [18]:The resulting current () was computed assuming the reversal potential matched that of voltage-gated Na+ channels ():

2.2.2. Integration into Electrophysiological Dynamics

2.2.3. Numerical Integration

- Fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4) with 1 ms step for HH dynamics,

- Forward Euler for Izhikevich spiking kinetics.

2.3. Postsynaptic Neuron Model

2.3.1. Spike Train Generation

2.3.2. Synaptic Conductance Dynamics

- Alpha Function for Glutamate Release. The time-dependent profile of glutamate release was modeled using a rectified alpha function [19]:where is the time constant of glutamate emission.

- Glutamate Concentration in the Synaptic Cleft. The total glutamate concentration at time t was computed as follows:where A is the amplitude of glutamate emission per spike (Table 1), and are the presynaptic spike times.

- Synaptic Conductance . The total synaptic conductance incorporated phosphorylation-dependent AMPA receptor modulation [20]:where

- : Maximal conductance of an AMPA receptor (Table 1),

- : Total number of AMPA receptors at synapse i,

- : Phosphorylation rate (), i.e the portion of phosphorylated receptors at synapse i (Table 1),

- , : Michaelis constants for phosphorylated/unphosphorylated states of the receptor (Table 1),

- : Glutamate concentration at synapse i.

2.3.3. Synaptic Current Integration

2.4. Global Network Architecture

2.4.1. Network Structure

- Input Layer: Composed of taste cells with varying arrangements of taste detectors (sweet, bitter, salty, sour). Each cell’s output was encoded as a binary spike train using the binning procedure described in Section 2.2.

- Hidden Layers: Consisting of postsynaptic neurons driven by glutamate-mediated synapses. The synaptic dynamics followed the phosphorylation-dependent conductance model [21]:where (if phosphorylated) or (otherwise), implementing activity-dependent plasticity.

2.4.2. The Multiscale Integration Approach

2.4.3. Synaptic Weight Representation and Plasticity

- Total AMPA receptors (): This parameter determines the baseline synaptic strength by representing the number of AMPA-type glutamate receptors available at the postsynaptic density. Synaptic efficacy is fundamentally limited by receptor availability [24].

- Phosphorylation state (): This variable models the activity-dependent modulation of receptor conductance via phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits (e.g., GluA1 at Ser845), a well-established cellular mechanism underlying spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) and LTP [21]. The phosphorylation dynamics were updated according to a spike-based Hebbian learning rule:where

- : Learning rate (fixed at 0.05), representing the timescale of biochemical cascades

- : Synchronization index for spike train pair j, quantifying the temporal correlation between pre- and postsynaptic activity [25]:where

- −

- : Minimal interspike interval between pre- and postsynaptic neurons in trial j

- −

- : Temporal resolution bin size (5 ms)

- −

- D: Maximum observed interspike interval across all trials.

- N: The number of spike train pairs.

2.4.4. Output Encoding

- bins (),

- m: Number of output neurons,

- Each entry indicated a spike in neuron j during bin i.

2.4.5. Information Flow

- Taste inputs → Spike trains via receptor dynamics (Modeling of individual taste cells subsection),

- Spike trains → Synaptic currents (Postsynaptic neuron model subsection),

- Currents → Output spikes through iterative membrane potential updates.

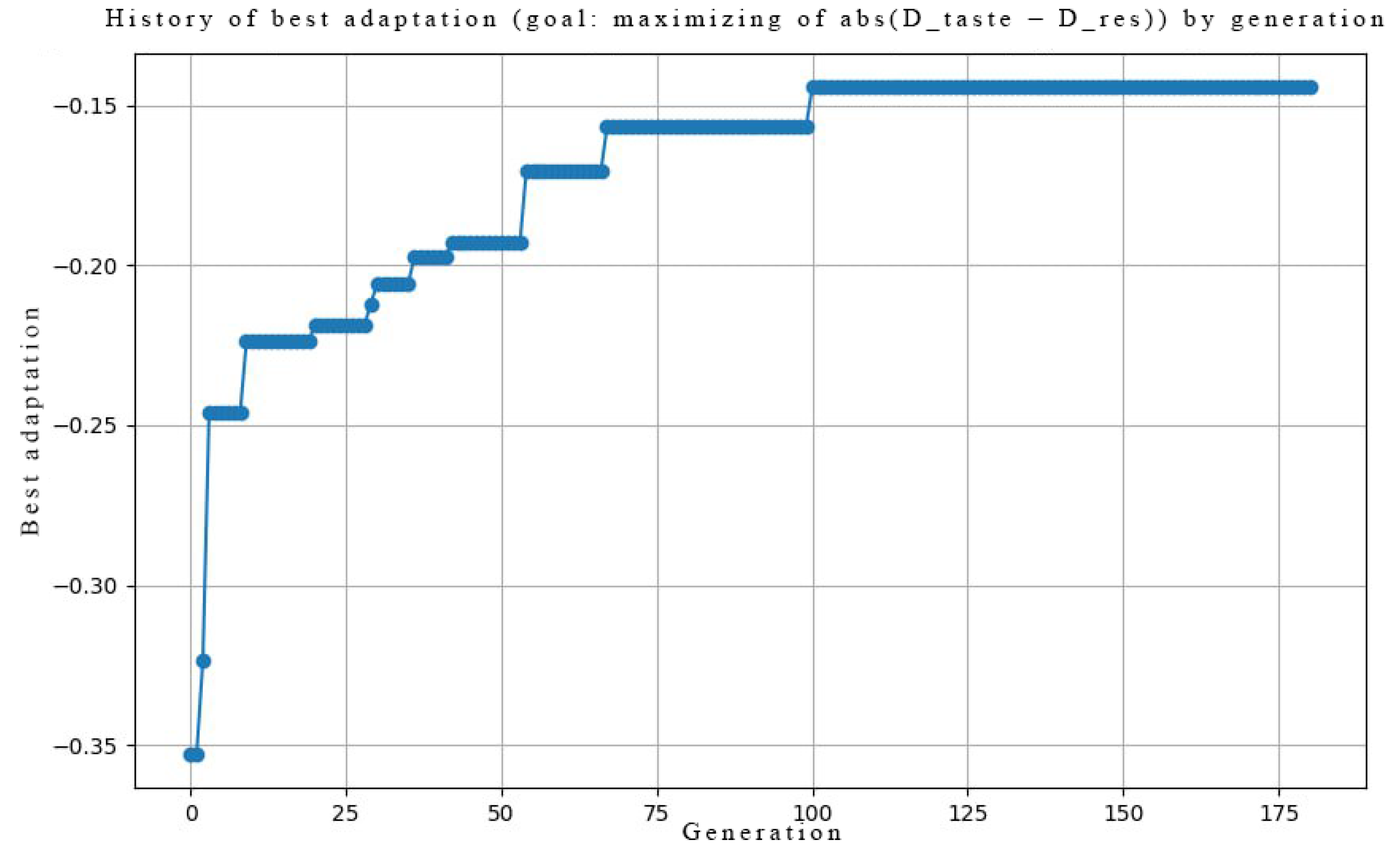

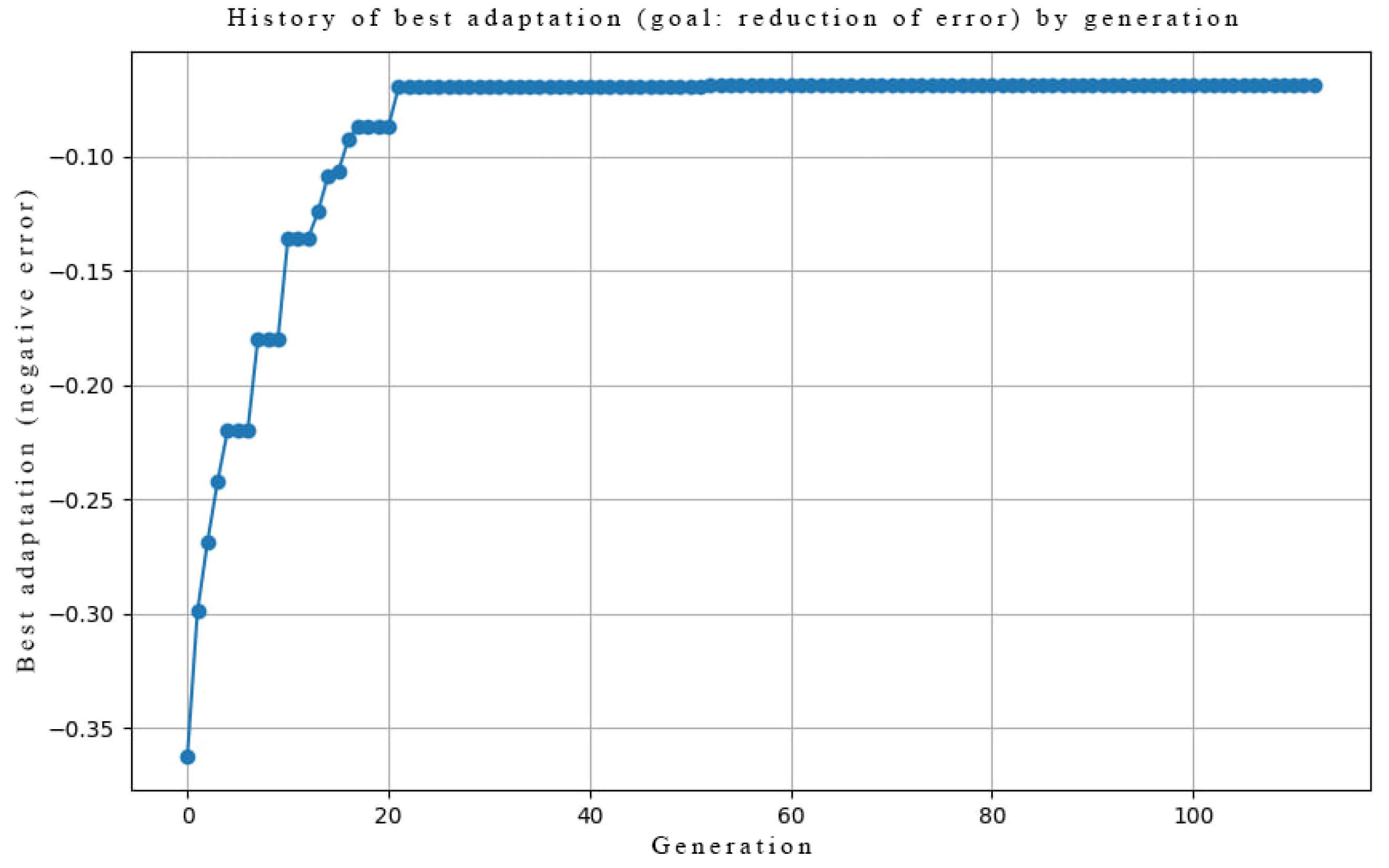

2.5. Learning

Genetic Optimization

- AMPA Receptor Counts : Optimized using a genetic algorithm with. This process functionally mimics homeostatic synaptic scaling, setting the maximal synaptic capacity over long timescales [29].

- −

- Population size: 100 individuals

- −

- Selection: Rank-based, keeping top 50% performers

- −

- Mutation: Gaussian noise ()

- −

- Crossover: Uniform mixing of parent parameters.

- Phosphorylation Rates (): Adapted online according to synaptic activity [24]:where is the mean in the best-performing individuals.

2.6. Parameter Values

| Parameter | Value | Description and Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5 ms | Glutamate emission time constant (alpha-function synapse kinetics) [4,31] | |

| A | 1.2 mM | Glutamate release amplitude (peak cleft concentration) [4,31] |

| 10 pS | Single AMPA receptor conductance (unitary channel) [32,33] | |

| 0.3 mM | Phosphorylated AMPA Michaelis constant (fitted from phosphorylation kinetics) [20,34] | |

| 1.5 mM | Unphosphorylated AMPA Michaelis constant (fitted from phosphorylation kinetics) [20,34] | |

| 0 mV | AMPA reversal potential (cation-nonselective channel) [35,36] | |

| 0.05 | Phosphorylation learning rate (STDP scaling parameter) [37,38,39] | |

| −50 mV | Spike detection threshold (HH model threshold) [40,41] |

2.7. Tasks

2.7.1. Task 1: Encoding Taste Pleasantness

- : Distance in taste pleasantness space for stimuli and :where

- −

- , = 50.0 (optimal NaCl concentration and width)

- −

- , (optimal acidity and width)

- −

- , = 10,000.0 (optimal sweetness and width)

- −

- , (optimal bitterness and width).

- : Information distance between output spike trains:with H as joint entropy and as mutual information.

2.7.2. Task 2: Taste Discrimination

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Procedure and Network Evaluation

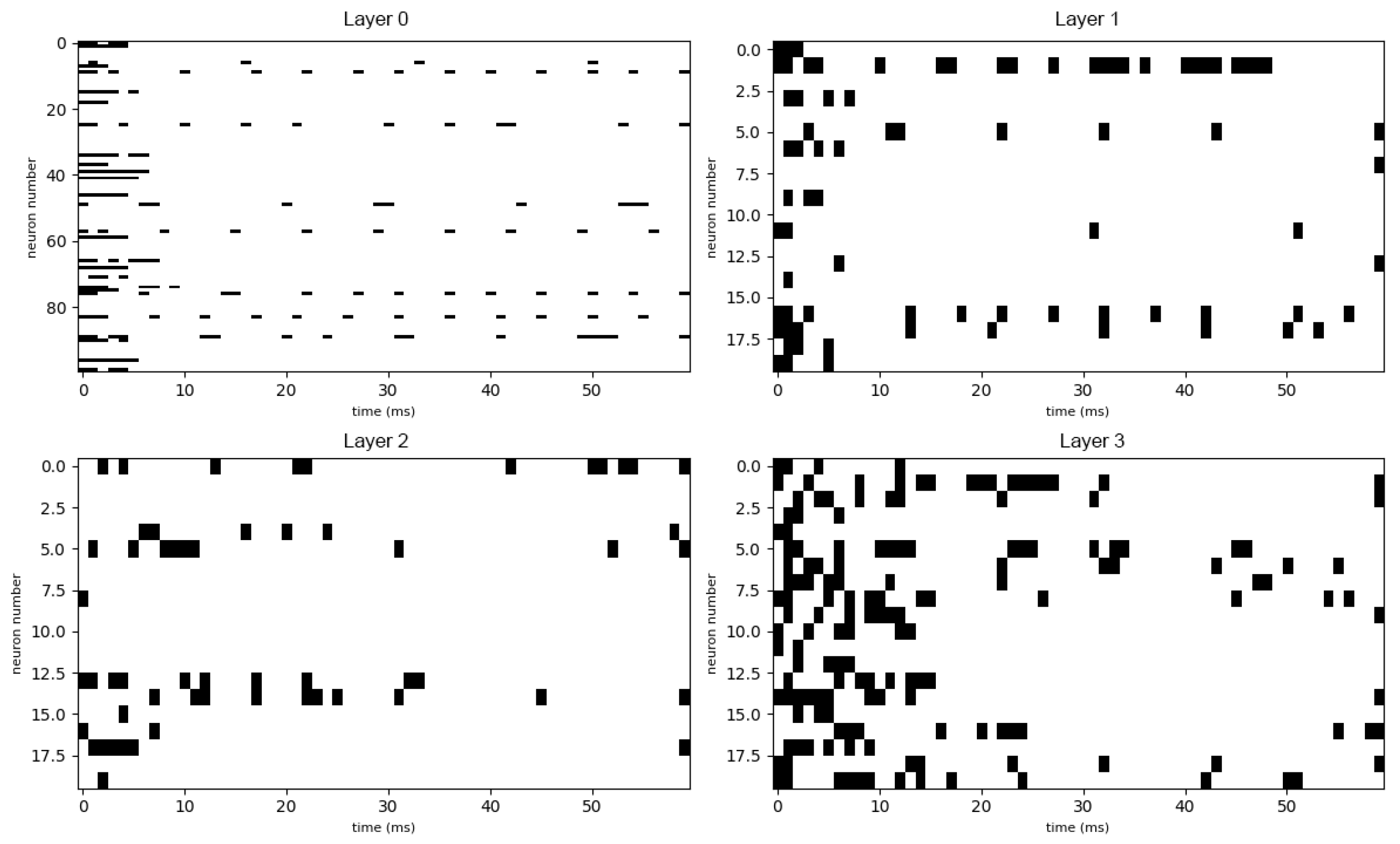

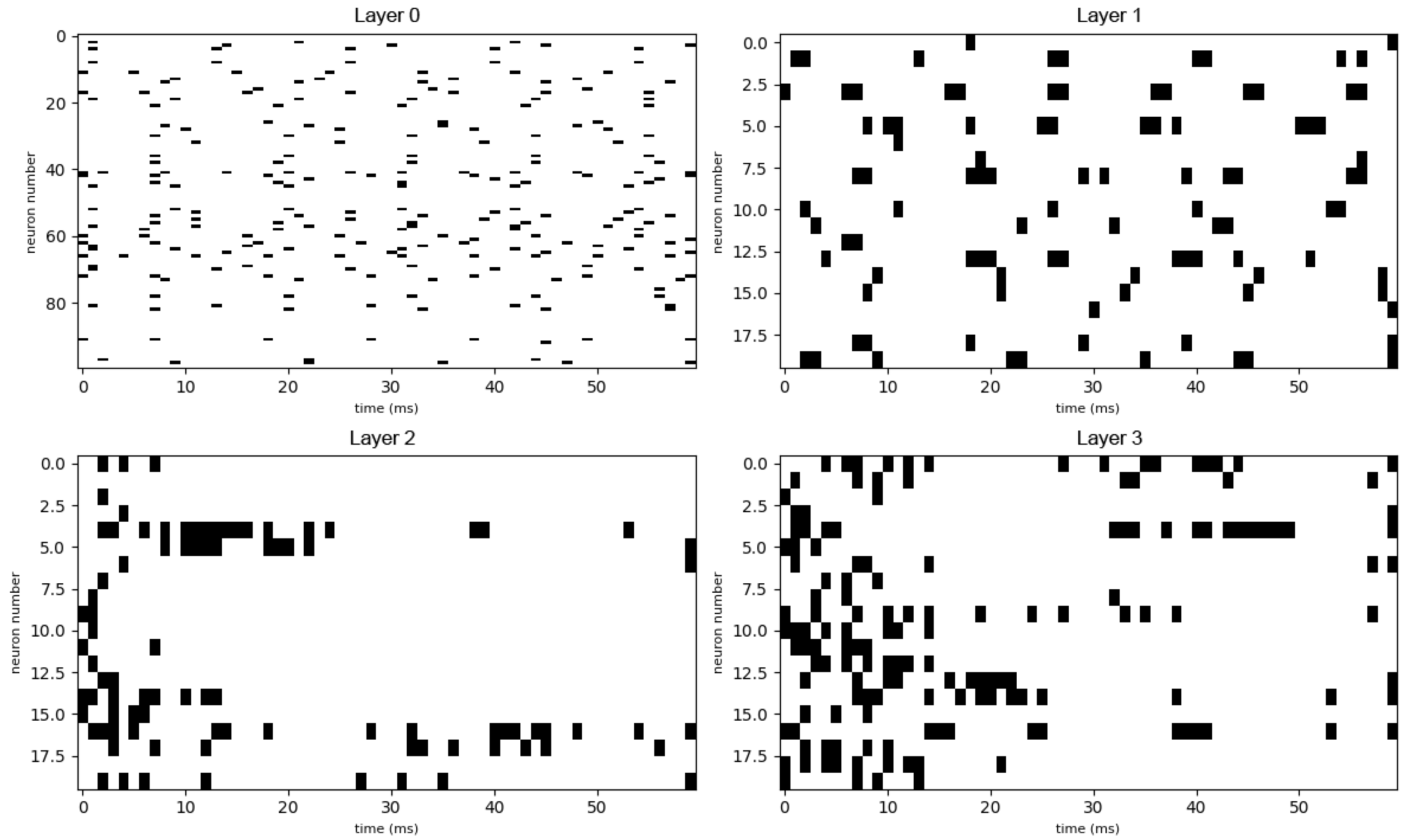

3.2. Untrained Network Responses

3.3. Learning Dynamics

3.4. Trained Network Responses and Taste Recognition

3.5. Quantitative Analysis of Neural Coding

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Model

- Biophysical Simplification: Although we utilized GHK and Michaelis–Menten equations to describe currents, the model omits many intricacies of intracellular signal transduction. For instance, for bitter, sweet, and umami tastes, the cascades of secondary messengers (IP3, DAG), the dynamics of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, and the subtle modulation of voltage-gated channels are not fully modeled. This may limit the accuracy of predicting responses to complex or low-concentration stimuli.

- Network Architecture: The feedforward architecture used is a significant simplification compared to the real gustatory system, which features abundant feedback loops both within taste buds and at the level of the brainstem and thalamus. These feedback connections play a crucial role in adaptation, habituation, and the modulation of taste perception by other modalities (e.g., olfaction).

- Influence of Other Sensory Modalities: As noted in the introduction, taste is closely integrated with olfaction, somatosensory (texture, temperature), and even visual sensations. Our current model is purely gustatory and does not account for this multisensory integration, which is fundamental for forming the holistic perception of “flavor”.

- Learning and Plasticity: Although we implemented an STDP-like rule for AMPA receptor phosphorylation, the learning mechanism was global and driven by an external genetic algorithm. In a real biological system, plasticity is local and distributed. Furthermore, the model lacks inhibitory interneurons, which are critical for forming contrastive and selective neural representations.

4.2. Robustness and Model Limitations

4.3. Future Directions and Model Development

- Multisensory Integration: The most evident development is the integration of an olfactory model. Following the same paradigm, a biomorphic model of the olfactory bulb could be created, where information is encoded by spatiotemporal spike patterns in glomeruli and mitral cells, and its output could be connected to the gustatory network. This would allow for the study of how combined taste-odor stimuli are encoded and discriminated at higher processing levels.

- Incorporating Feedback and Inhibition: Extending the network architecture by including recurrent connections and populations of inhibitory interneurons (e.g., based on the Izhikevich model) would enable more complex and robust dynamic regimes, such as synchronization and competitive interaction (“winner-take-all”), bringing the model closer to its biological prototype.

- Deepening Intracellular Signaling: The model can be made more detailed by incorporating comprehensive models of calcium dynamics and G-protein cascades for metabotropic receptors, using stochastic or deterministic systems of differential equations.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Additional Graphs

References

- Chaudhari, N.; Roper, S. The cell biology of taste. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, D.; Medler, K. Bitter, sweet, and umami signaling in taste cells: It’s not as simple as we thought. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruno, A.; Vingtdeux, V.; Ohmoto, M.; Ma, Z.; Dvoryanchikov, G.; Li, A.; Adrien, L.; Zhao, H.; Leung, S.; Abernethy, M.; et al. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature 2013, 495, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.; Lester, R.; Tong, G.; Jahr, C.; Westbrook, G. The time course of glutamate in the synaptic cleft. Science 1992, 258, 1498–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, K.; Yoshii, K.; Ohtubo, Y.; Miki, T. A network model toward a taste bud inspired sensor. Int. Congr. Ser. 2007, 1301, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltic, S.; Wysoski, S.; Kasabov, N. Evolving spiking neural networks for taste recognition. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), Hong Kong, China, 1–8 June 2008; pp. 2091–2097. [Google Scholar]

- Lvova, L.; Kim, S.S.; Legin, A.; Vlasov, Y.; Yang, J.S.; Cha, G.S.; Nam, H. All-solid-state electronic tongue and its application for beverage analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 468, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Jain, D.; Gupta, R.; Rai, B. Classification of tastants: A deep learning based approach. Mol. Inform. 2023, 42, e202300146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhof, W.; Batram, C.; Kuhn, C.; Brockhoff, A.; Chudoba, E.; Bufe, B.; Appendino, G.; Behrens, M. The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chem. Senses 2010, 35, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbeuch, A.; Clapp, T.; Kinnamon, S. Amiloride-sensitive channels in type I fungiform taste cells in mouse. BMC Neurosci. 2008, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Maruyama, Y.; Stimac, R.; Roper, S. Presynaptic (Type III) cells in mouse taste buds sense sour (acid) taste. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 2903–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.; Waters, H.; Liman, E. A proton current drives action potentials in genetically identified sour taste cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22320–22325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Chaudhari, N. Taste buds: Cells, signals and synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunning, M.; Tagkopoulos, I. A systematic review of data and models for predicting food flavor and texture. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 11, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Androutsos, O.; Pallante, L.; Bompotas, A.; Stojceski, F.; Grasso, G.; Piga, D.; Di Benedetto, G.; Alexakos, C.; Kalogeras, A.; Theofilatos, K.; et al. Predicting multiple taste sensations with a multiobjective machine learning method. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenkwan, P.; Yana, J.; Nantasenamat, C.; Hasan, M.M.; Shoombuatong, W. iUmami-SCM: A novel sequence-based predictor for prediction and analysis of umami peptides using a scoring card method with propensity scores of dipeptides. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6666–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Weiss, J.N. The Hill equation revisited: Uses and misuses. FASEB J. 1997, 11, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rall Rall, W. Distinguishing theoretical synaptic potentials computed for different soma-dendritic distributions of synaptic input. J. Neurophysiol. 1967, 30, 1138–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, G.; Bazzani, A.; Cooper, L. Toward a microscopic model of bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14091–14095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Barbarosie, M.; Kameyama, K.; Bear, M.; Huganir, R. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature 2000, 405, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E.; Edelman, G. Large-scale model of mammalian thalamocortical systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3593–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markram, H.; Muller, E.; Ramaswamy, S.; Reimann, M.W.; Abdellah, M.; Sanchez, C.A.; Ailamaki, A.; Alonso-Nanclares, L.; Antille, N.; Arsever, S.; et al. Reconstruction and simulation of neocortical microcircuitry. Cell 2015, 163, 456–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinow, R.; Malenka, R. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 25, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Miller, K.; Abbott, L. Competitive Hebbian Learning through Spike-Timing-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Shi, S.; Esteban, J.; Piccini, A.; Poncer, J.; Malinow, R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: Requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science 2000, 287, 2262–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benke, T.; Lüthi, A.; Isaac, J.; Collingridge, G. Mathematical modelling of non-stationary fluctuation analysis for studying channel properties of synaptic AMPA receptors. J. Physiol. 1998, 537, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Poo, M. Synaptic modification by correlated activity: Hebb’s postulate revisited. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrigiano Turrigiano, G.G. The self-tuning neuron: Synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell 2008, 135, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossum, M. A Novel Spike Distance. Neural Comput. 2001, 13, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J. Glutamate release monitored with astrocyte transporter currents during LTP. Neuron 2005, 45, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, G.; Kamboj, S.; Cull-Candy, S. Single-channel properties of recombinant AMPA receptors depend on RNA editing, splice variation, and subunit composition. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Wang, L.; Howe, J. Heterogeneous conductance levels of native AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 2073–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallimore, A.; Aricescu, A.; Yuzaki, M.; Calinescu, R. A Computational Model for the AMPA Receptor Phosphorylation Master Switch Regulating Cerebellar Long-Term Depression. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, M.; Hartley, M.; Heinemann, S. Ca2+ permeability of KA-AMPA–gated glutamate receptor channels depends on subunit composition. Science 1991, 252, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnashev, N.; Khodorova, A.; Jonas, P.; Helm, P.; Wisden, W.; Monyer, H.; Seeburg, P.; Sakmann, B. Calcium-permeable AMPA-kainate receptors in fusiform cerebellar glial cells. Science 1992, 256, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J.; Gerstner, W. Spike-timing dependent plasticity. Scholarpedia 2010, 5, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, M.; Masquelier, T.; Hugues, E. STDP Allows Fast Rate-Modulated Coding with Poisson-Like Spike Trains. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Characterization of generalizability of spike timing dependent plasticity trained spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 695357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E. Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2003, 14, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkin, A.; Huxley, A. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952, 117, 500–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breza, J.; Nikonov, A.; Contreras, R. Response latency to lingual taste stimulation distinguishes neuron types within the geniculate ganglion. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 103, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V.; Nikonov, A.; Wu, W.; Contreras, R. Spike rate and spike timing contributions to coding taste quality information in the rat geniculate ganglion. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, P.; Victor, J. Taste response variability and temporal coding in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 90, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussin, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Fooden, A.; Victor, J.; Di Lorenzo, P. Taste coding in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the awake, freely licking rat. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 10494–10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, A.; Bucher, D.; Marder, E. Similar network activity from disparate circuit parameters. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, T.; Williams, A.; Franci, A.; Marder, E. Correlations in ion channel expression emerge from homeostatic regulation rules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E2645–E2654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stasenko, S.; Mikhaylov, A.; Kazantsev, V. Model of neuromorphic odorant-recognition network. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lazovsky, V.A.; Stasenko, S.V.; Khismatullin, R.K.; Kazantsev, V.B. Computational Advances in Taste Perception: From Ion Channels and Taste Receptors to Neural Coding. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010010

Lazovsky VA, Stasenko SV, Khismatullin RK, Kazantsev VB. Computational Advances in Taste Perception: From Ion Channels and Taste Receptors to Neural Coding. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazovsky, Vladimir A., Sergey V. Stasenko, Roman K. Khismatullin, and Victor B. Kazantsev. 2026. "Computational Advances in Taste Perception: From Ion Channels and Taste Receptors to Neural Coding" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010010

APA StyleLazovsky, V. A., Stasenko, S. V., Khismatullin, R. K., & Kazantsev, V. B. (2026). Computational Advances in Taste Perception: From Ion Channels and Taste Receptors to Neural Coding. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010010