Do We View Robots as We Do Ourselves? Examining Robotic Face Processing Using EEG

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

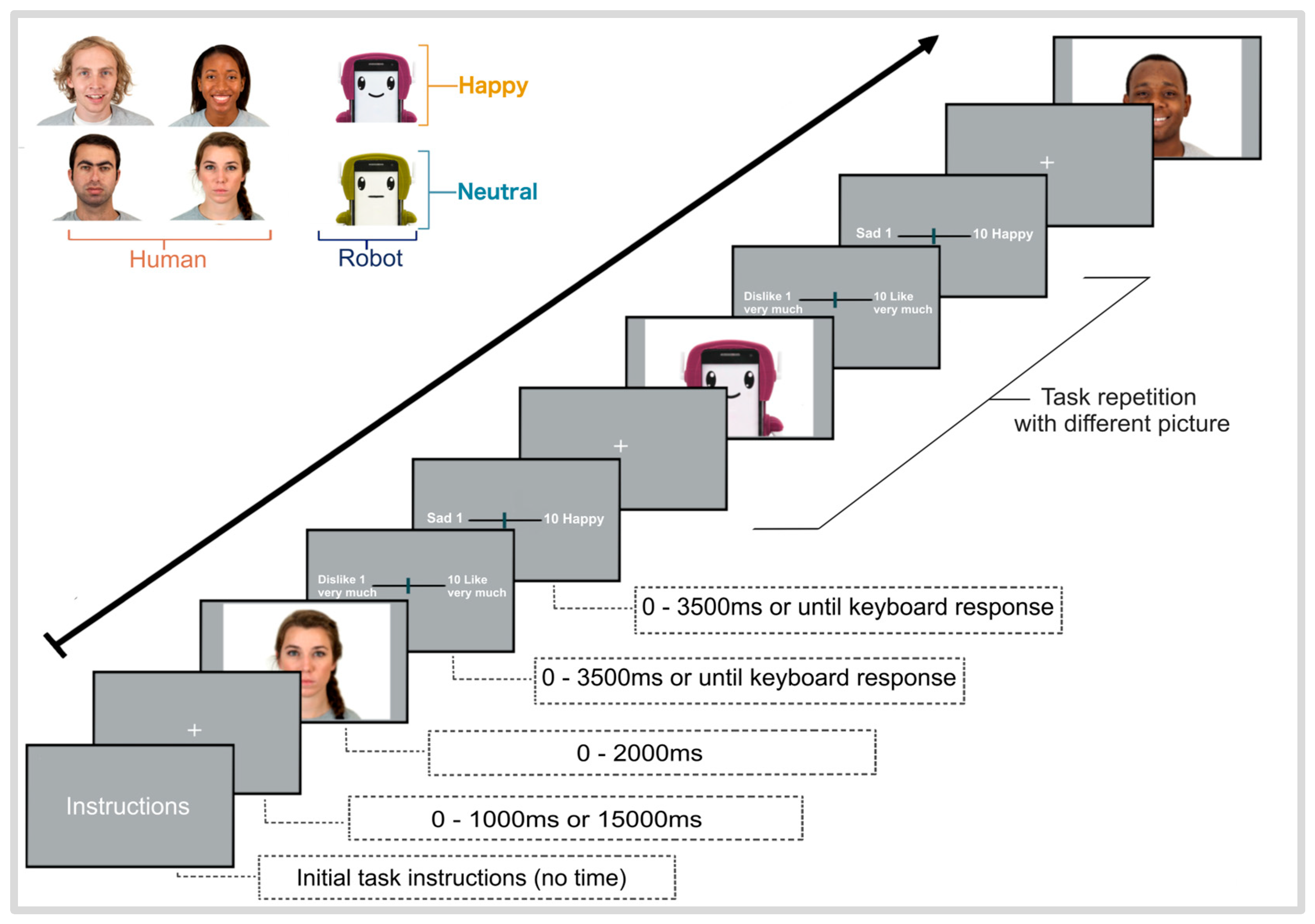

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Stimuli

2.4. EEG Recordings

2.5. Behavioral Measures

2.6. Electrophysiological Data Preprocessing

2.7. ERP Analysis

2.8. Behavioral Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Negative Attitudes Towards Robots (NARS) Scores

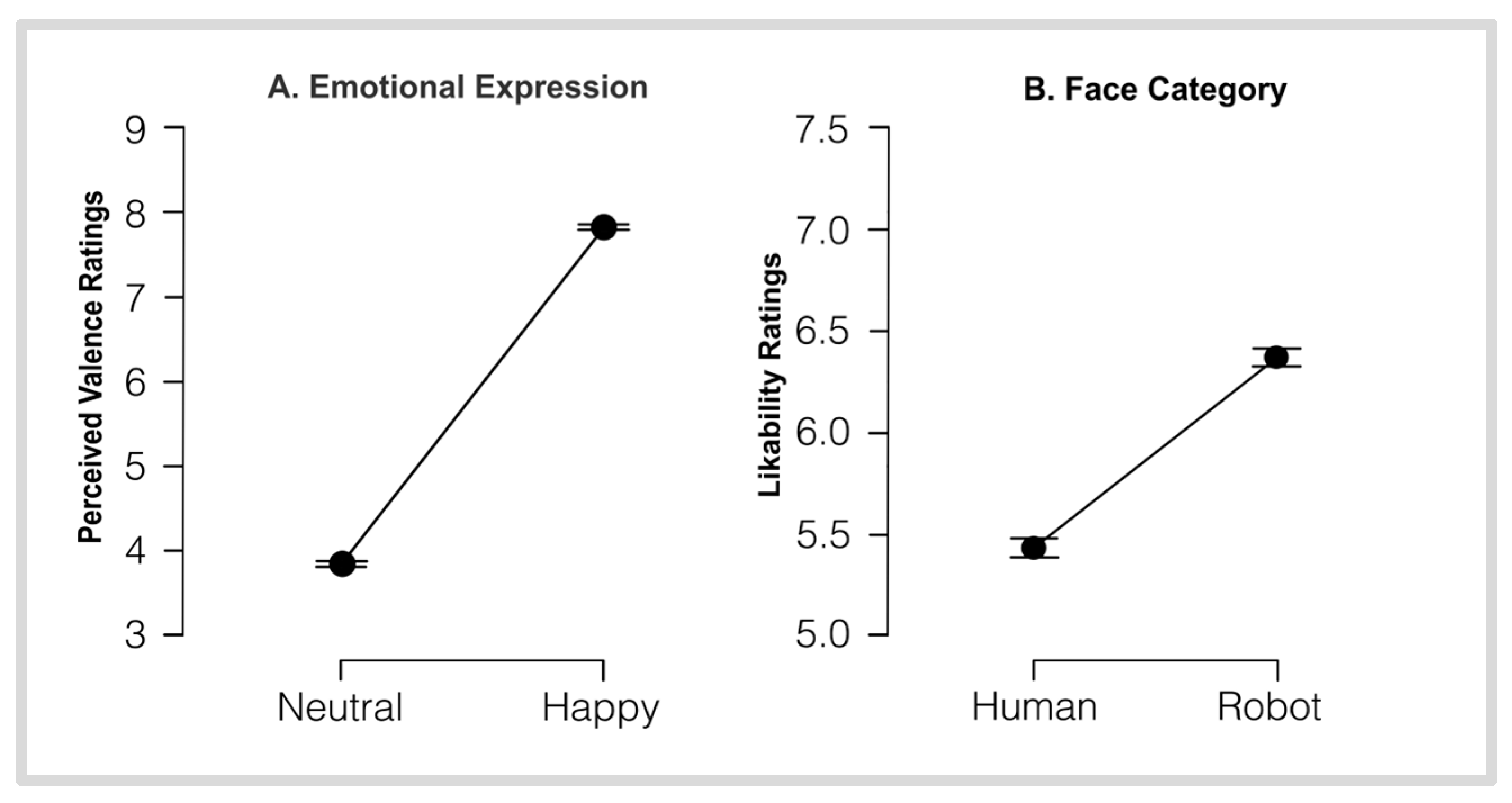

3.2. VAS Rating Scores

3.3. ERP’s Results

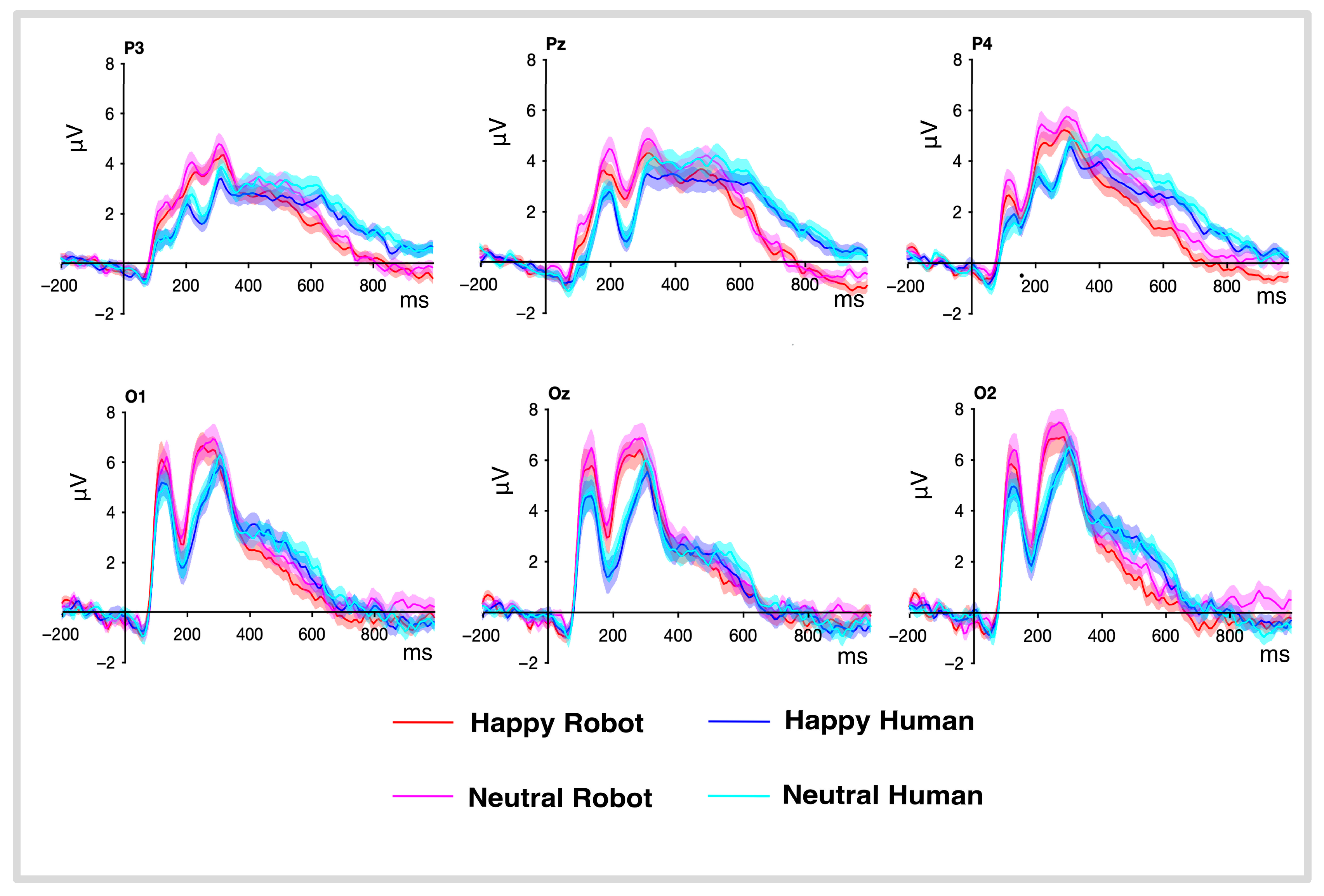

3.3.1. P100

3.3.2. N170

3.3.3. P300

3.3.4. P600

3.3.5. ERP’s Summary

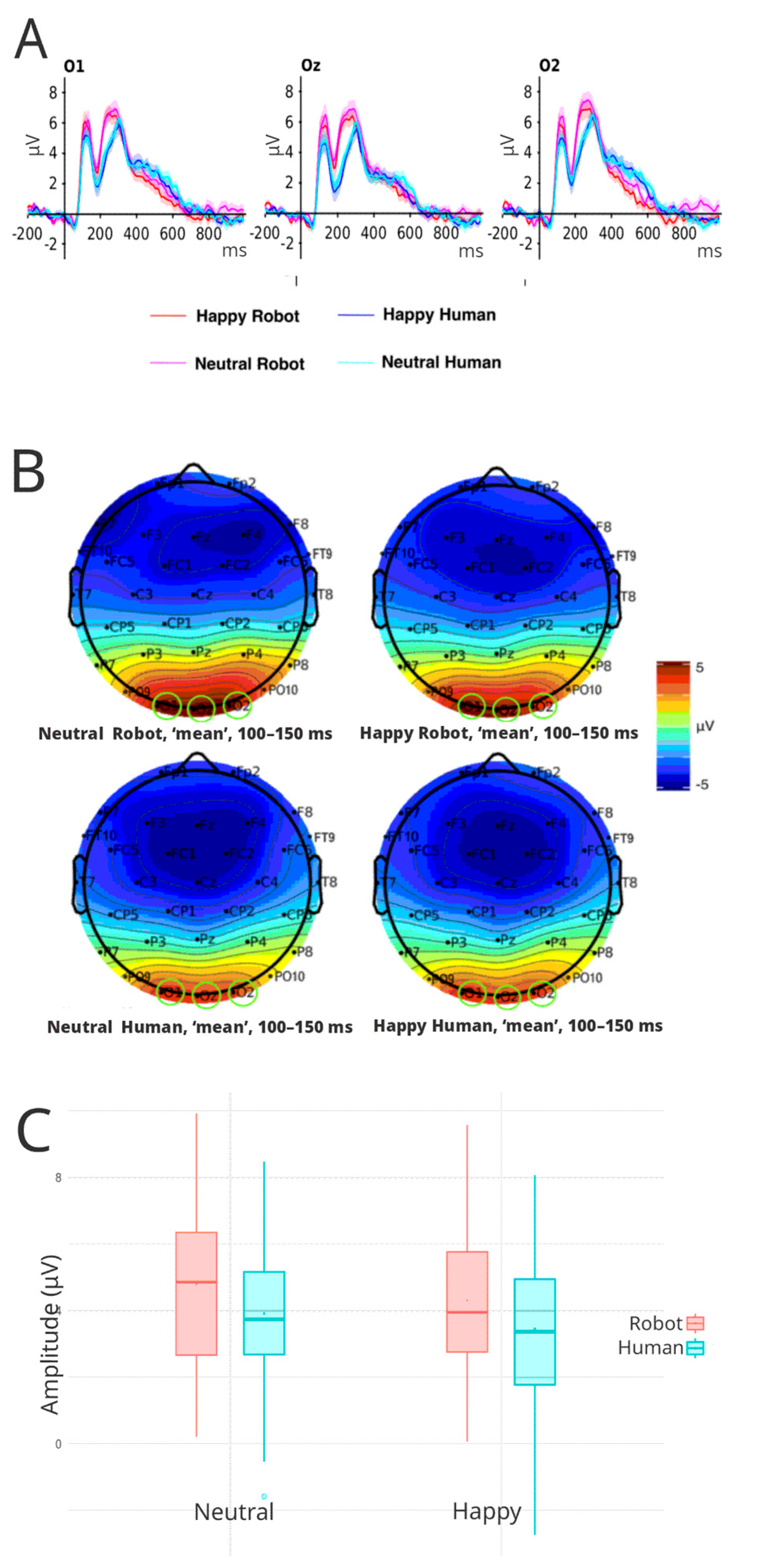

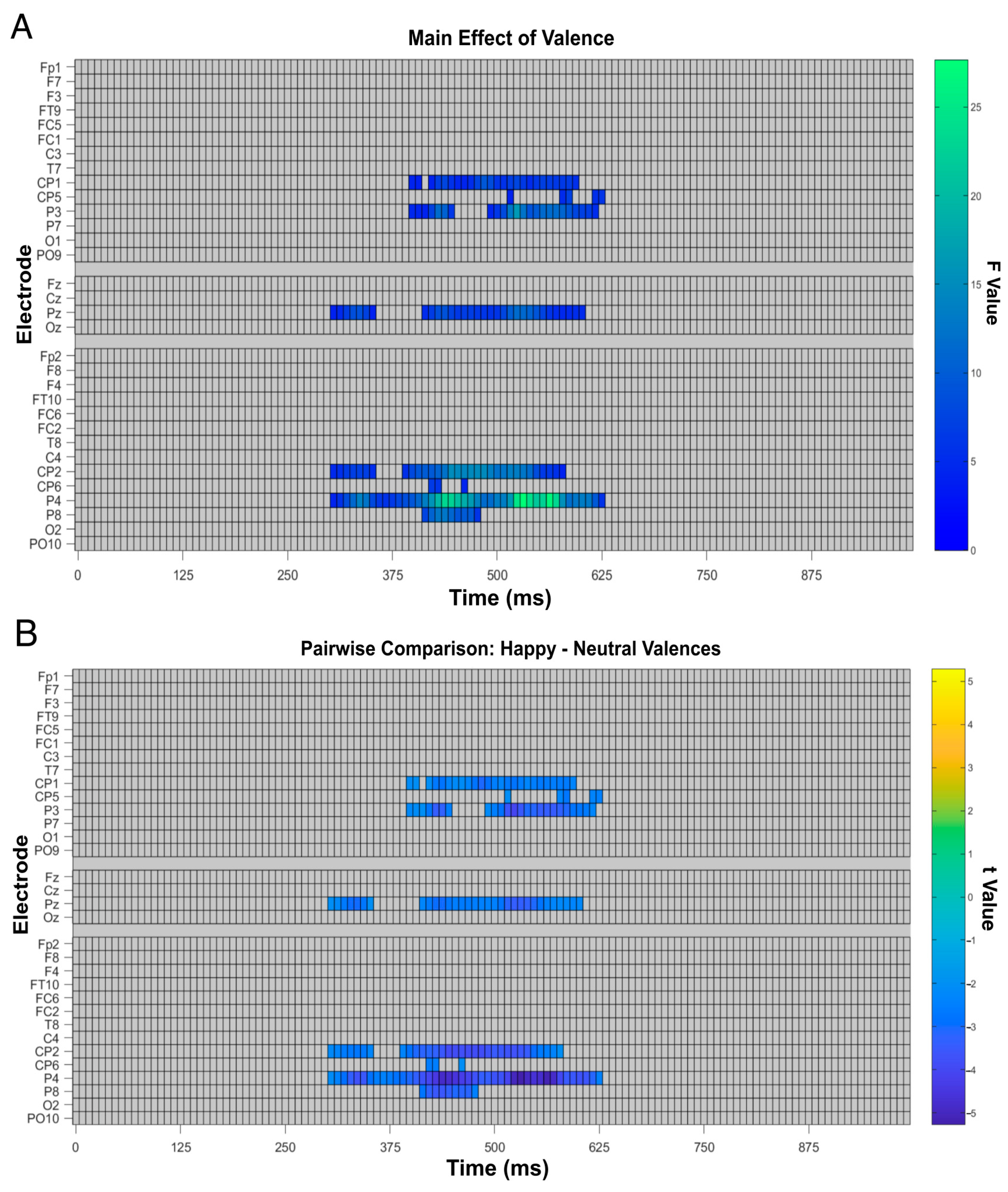

3.4. Factorial Mass Univariate Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ERP | Event-related potential |

| FMUT | Functional mass univariate analysis toolbox |

| NARS | Negative Attitudes Towards Robots Scale |

| VPP | Vertex positive potential |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Sabatinelli, D.; Fortune, E.E.; Li, Q.; Siddiqui, A.; Krafft, C.; Oliver, W.T.; Jeffries, J. Emotional perception: Meta-analyses of face and natural scene processing. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 2524–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retter, T.L.; Jiang, F.; Webster, M.A.; Rossion, B. All-or-none face categorization in the human brain. NeuroImage 2020, 213, 116685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, A.; Kliger, L.; Yovel, G. Learning Faces as Concepts Improves Face Recognition by Engaging the Social Brain Network. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullrich, D.; Diefenbach, S. Truly social robots: Understanding human–robot interaction from the perspective of social psychology. In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2017), Porto, Portugal, 27 February–1 March 2017; SciTePress: Porto, Portugal, 2017; pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Hawkins, R.; Sharlin, E.; Igarashi, T. Toward acceptable domestic robots: Applying insights from social psychology. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2009, 1, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, C. Me and My Robot Smiled at One Another: The process of socially enacted communicicative affordance in human–machine communication. Hum.-Mach. Commun. 2020, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, J.; Al-Hindawi, A.; Ng, T.; Vizcaychipi, M.P. Scoping review on the use of socially assistive robot technology in elderly care. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airenti, G. The Cognitive Bases of Anthropomorphism: From Relatedness to Empathy. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, W.; Xue, C. How the Degree of Anthropomorphism of Human-Like Robots Affects Users’ Perceptual and Emotional Processing: Evidence from an EEG Study. Sensors 2024, 24, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, A.S.; Ham, J.; Barakova, E.I.; Markopoulos, P. Effects of Robot Facial Characteristics and Gender in Persuasive Human–Robot Interaction. Front. Robot. AI 2018, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.Q.; Felding, S.A.; Budak, K.B.; Toomey, E.; Casey, D. Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of Social Robots for Older Adults and People with Dementia: A Scoping Review. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Gong, J. Early ERP Components to Emotional Facial Expressions in Young Adult Victims of Childhood Maltreatment. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 275, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Buchanan, T.W.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L. Acute Psychological Stress Disrupts Attentional Bias to Threat-Related Stimuli. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, H.; Kawabe, K.; Shigemi, S.; Arai, T. Relationship between Familiarity and Humanness of Robots—Quantification of Psychological Impressions toward Humanoid Robots. Adv. Robot. 2014, 28, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Ishiguro, H.; Ishida, T. Psychological Analysis on Human–Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–26 May 2001; IEEE: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001; Volume 4, pp. 4166–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, E.; Manzey, D.; Onnasch, L. A Meta-Analysis on the Effectiveness of Anthropomorphism in Human–Robot Interaction. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabj5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubshait, A.; Wiese, E. You Look Human, but Act like a Machine: Agent Appearance and Behavior Modulate Different Aspects of Human–Robot Interaction. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woerdt, S.; Haselager, P. When Robots Appear to Have a Mind: The Human Perception of Machine Agency and Responsibility. New Ideas Psychol. 2019, 54, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J. Effects of a Cognitive-Based Intervention Program Using Social Robot PIO on Cognitive Function, Depression, Loneliness, and Quality of Life of Older Adults Living Alone. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1097485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoglio, A.A.J.; Reilly, E.D.; Gorman, J.A.; Drebing, C.E. Use of Social Robots in Mental Health and Well-Being Research: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guemghar, I.; de Oliveira, P.; Padilha, P.; Abdel-Baki, A.; Jutras-Aswad, D.; Paquette, J.; Pomey, M.P. Social Robot Interventions in Mental Health Care and Their Outcomes, Barriers, and Facilitators: Scoping Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e36094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haist, F.; Anzures, G. Functional Development of the Brain’s Face-Processing System. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 2017, 8, e1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwisher, N.; Yovel, G. The Fusiform Face Area: A Cortical Region Specialized for the Perception of Faces. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006, 361, 2109–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiwald, W.A. The Neural Mechanisms of Face Processing: Cells, Areas, Networks, and Models. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 60, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, G.; Barragan-Jason, G.; Thorpe, S.; Fabre-Thorpe, M.; Puma, S.; Ceccaldi, M.; Barbeau, E. From Face Processing to Face Recognition: Comparing Three Different Processing Levels. Cognition 2017, 158, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, S.; Deouell, L.Y. Structural Encoding and Identification in Face Processing: ERP Evidence for Separate Mechanisms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2000, 17, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itier, R.J.; Taylor, M.J. Face Inversion and Contrast-Reversal Effects across Development: In Contrast to the Expertise Theory. Dev. Sci. 2004, 7, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dering, B.; Martin, C.D.; Moro, S.; Pegna, A.J.; Thierry, G. Face-Sensitive Processes One Hundred Milliseconds after Picture Onset. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, S.; Allison, T.; Puce, A.; Perez, E.; McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological Studies of Face Perception in Humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuefner, D.; de Heering, A.; Jacques, C.; Palmero-Soler, E.; Rossion, B. Early Visually Evoked Electrophysiological Responses over the Human Brain (P1, N170) Show Stable Patterns of Face-Sensitivity from 4 Years to Adulthood. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. Face-Sensitive P1 and N170 Components Are Related to the Perception of Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional Objects. NeuroReport 2018, 29, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, E.H.; Smulders, F.T.Y.; Merckelbach, H.L.G.J.; Wolf, A.G. The P300 Is Sensitive to Concealed Face Recognition. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007, 66, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretié, L.; Iglesias, J.; García, T.; Ballesteros, M. N300, P300 and the Emotional Processing of Visual Stimuli. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1997, 103, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhang, L.; Meng, P.; Meng, X.; Weng, M. The Neural Responses of Visual Complexity in the Oddball Paradigm: An ERP Study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassenhagen, J.; Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, I. The P600 as a Correlate of Ventral Attention Network Reorientation. Cortex 2015, 66, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassenhagen, J.; Fiebach, C.J. Finding the P3 in the P600: Decoding Shared Neural Mechanisms of Responses to Syntactic Violations and Oddball Targets. NeuroImage 2019, 200, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contier, F.; Höger, M.; Rabovsky, M. The P600 during Sentence Reading Predicts Behavioral and Neural Markers of Recognition Memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2025, 37, 2632–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.; Vaidyanathan, R.; James, C.; Melhuish, C. Assessment of Human Response to Robot Facial Expressions through Visual Evoked Potentials. In Proceedings of the 2010 10th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids), Nashville, TN, USA, 6–8 December 2010; IEEE: Nashville, TN, USA, 2010; pp. 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollfrank, T.; Kohnen, O.; Hilfiker, P.; Kegel, L.C.; Jokeit, H.; Brugger, P.; Loertscher, M.L.; Rey, A.; Mersch, D.; Sternagel, J.; et al. The Effects of Dynamic and Static Emotional Facial Expressions of Humans and Their Avatars on the EEG: An ERP and ERD/ERS Study. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 651044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimardani, M.; Hiraki, K. Passive Brain-Computer Interfaces for Enhanced Human-Robot Interaction. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosch, T.; Karolus, J.; Zagermann, J.; Reiterer, H.; Schmidt, A.; Woźniak, P.W. A Survey on Measuring Cognitive Workload in Human-Computer Interaction. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durston, A.J.; Itier, R.J. The Early Processing of Fearful and Happy Facial Expressions Is Independent of Task Demands—Support from Mass Univariate Analyses. Brain Res. 2021, 1765, 147505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, A.R.; Balas, B. Robot Faces Elicit Responses Intermediate to Human Faces and Objects at Face-Sensitive ERP Components. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubal, S.; Foucher, A.; Jouvent, R.; Nadel, J. Human Brain Spots Emotion in Non-Humanoid Robots. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011, 6, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gift, A.G. Visual Analogue Scales: Measurement of Subjective Phenomena. Nurs. Res. 1989, 38, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.S.; Correll, J.; Wittenbrink, B. The Chicago Face Database: A Free Stimulus Set of Faces and Norming Data. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SimaRobot. Available online: http://web.simarobot.com/ (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Shibata, T. Therapeutic Seal Robot as Biofeedback Medical Device: Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluations of Robot Therapy in Dementia Care. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Gelin, R. A Mass-Produced Sociable Humanoid Robot: Pepper: The First Machine of Its Kind. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2018, 25, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Yussof, H.; Nasir, H.W.; Zahari, N.I.; Hamed, S.B.; Hashim, H.; Johari, A. Humanoid Robot NAO: Review of Control and Motion Exploration. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Robotics and Intelligent Sensors (IRIS), Penang, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2011; IEEE: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2011; pp. 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabu Robot. Available online: https://robotsguide.com/robots/mabu (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Kompai Assist. Kompai Robotics. Available online: https://www.kompairobotics.com/en_US/kompai-assist (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Williams, N.S.; McArthur, G.M.; Badcock, N.A. It’s All about Time: Precision and Accuracy of Emotiv Event-Marking for ERP Research. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.; McArthur, G.M.; de Wit, B.; Ibrahim, G.; Badcock, N.A. A Validation of Emotiv EPOC Flex Saline for EEG and ERP Research. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMOTIV. Flex 2.0 User Manual: Technical Specifications. Available online: https://emotiv.gitbook.io/flex-2.0-user-manual/introduction/technical-specifications (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- EMOTIV. “What Is EEG Quality in the EmotivPRO?” EMOTIV Knowledge Base. Available online: https://emotiv.gitbook.io/emotivpro-v3/emotivpro-menu/contact-quality-map/contact-quality-cq-vs.-eeg-quality-eq (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Nomura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kanda, T.; Kato, K. Measurement of Negative Attitudes toward Robots. Interact. Stud. 2006, 7, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartneck, C.; Nomura, T.; Kanda, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kato, K. Cultural Differences in Attitudes Towards Robots. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Robot Companions: Hard Problems and Open Challenges in Robot-Human Interaction, Hatfield, UK, 12–15 April 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An Open Source Toolbox for Analysis of Single-Trial EEG Dynamics Including Independent Component Analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Calderon, J.; Luck, S.J. ERPLAB: An Open-Source Toolbox for the Analysis of Event-Related Potentials. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pion-Tonachini, L.; Kreutz-Delgado, K.; Makeig, S. ICLabel: An Automated Electroencephalographic Independent Component Classifier, Dataset, and Website. Neuroimage 2019, 198, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, F.; Liu, Q.; Wen, X.; Lai, Y.; Xu, P.; Yao, D. MATLAB Toolboxes for Reference Electrode Standardization Technique (REST) of Scalp EEG. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppe, D.M.; Urbach, T.P.; Kutas, M. Mass Univariate Analysis of Event-Related Brain Potentials/Fields II: Simulation Studies. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, E.C.; Kuperberg, G.R. Having Your Cake and Eating It Too: Flexibility and Power with Mass Univariate Statistics for ERP Data. Psychophysiology 2020, 57, e13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernet, C.R.; Latinus, M.; Nichols, T.E.; Rousselet, G.A. Cluster-Based Computational Methods for Mass Univariate Analyses of Event-Related Brain Potentials/Fields: A Simulation Study. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 250, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP, Version 0.16.1; [Computer Software]; JASP: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Nomura, T.; Suzuki, T. Altered Attitudes of People toward Robots: Investigation through the Negative Attitudes toward Robots Scale. 2006. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228368017 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Abubshait, A.; Weis, P.P.; Momen, A.; Wiese, E. Perceptual Discrimination in the Face Perception of Robots Is Attenuated Compared to Humans. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, U.; Signal, N.; Niazi, I.K.; Taylor, D. ERP Based Measures of Cognitive Workload: A Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 118, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, C.M.; Henderson, H.; Mundy, P.; Newell, L.; Jaime, M. Developmental and Individual Differences on the P1 and N170 ERP Components in Children with and without Autism. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2011, 36, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momen, A.; Kurt, H.; Wiese, E. Robots Engage Face-Processing Less Strongly than Humans. Front. Neuroergon. 2022, 3, 959578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganis, G.; Smith, D.; Schendan, H.E. The N170, Not the P1, Indexes the Earliest Time for Categorical Perception of Faces, Regardless of Interstimulus Variance. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergent, J. About Face: Left-Hemisphere Involvement in Processing Physiognomies. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1982, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, I.; García Alanis, J.C.; Volk, J.; Vogelbacher, C.; Steinsträter, O.; Jansen, A. Let’s Face It: The Lateralization of the Face Perception Network as Measured with fMRI Is Not Clearly Right Dominant. Neuroimage 2022, 263, 119587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Bublatzky, F. Attention and Emotion: An Integrative Review of Emotional Face Processing as a Function of Attention. Cortex 2020, 132, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellecke, J.; Sommer, W.; Schacht, A. Emotion Effects on the N170: A Question of Reference? Brain Topogr. 2013, 26, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahne, A.; Friederici, A.D. Differential Task Effects on Semantic and Syntactic Processes as Revealed by ERPs. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2002, 13, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, H.; Fitz, H.; Hoeks, J. Getting Real about Semantic Illusions: Rethinking the Functional Role of the P600 in Language Comprehension. Brain Res. 2012, 1446, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regel, S.; Meyer, L.; Gunter, T.C. Distinguishing Neurocognitive Processes Reflected by P600 Effects: Evidence from ERPs and Neural Oscillations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitonytė, J.; Alimardani, M.; Louwerse, M.M. Scoping Review of the Neural Evidence on the Uncanny Valley. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 9, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajcak, G.; Nieuwenhuis, S. Reappraisal Modulates the Electrocortical Response to Unpleasant Pictures. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2006, 6, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.A.; Cacioppo, J.T. Electrophysiological Evidence of Implicit and Explicit Categorization Processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 36, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.K.; Nordin, S.; Sequeira, H.; Polich, J. Affective Picture Processing: An Integrative Review of ERP Findings. Biol. Psychol. 2008, 77, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Zell, E.; Botsch, M.; Kissler, J. Differential Effects of Face-Realism and Emotion on Event-Related Brain Potentials and Their Implications for the Uncanny Valley Theory. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Quadflieg, S. In Our Own Image? Emotional and Neural Processing Differences When Observing Human–Human vs. Human–Robot Interactions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S. High-Speed Scanning in Human Memory. Science 1966, 153, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinss, M.F.; Brock, A.M.; Roy, R.N. Cognitive Effects of Prolonged Continuous Human-Machine Interaction: The Case for Mental State-Based Adaptive Interfaces. Front. Neuroergon. 2022, 3, 935092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Byrne, A.K.; Headley, A.; Sanders, J.G.; Petrie, H.; Jenkins, R.; Baker, D.H. Neural Correlates of the Uncanny Valley Effect for Robots and Hyper-Realistic Masks. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0311714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnebusch, D.A.; Suchan, B.; Köster, O.; Daum, I. A Bilateral Occipitotemporal Network Mediates Face Perception. Behav. Brain Res. 2009, 198, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.D. Differential Hemispheric Lateralization of Emotions and Related Display Behaviors: Emotion-Type Hypothesis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenfort, J.J. Multivariate Methods to Track the Spatiotemporal Profile of Feature-Based Attentional Selection Using EEG. Neuromethods 2020, 151, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppe, D.M.; Urbach, T.P.; Kutas, M. Mass Univariate Analysis of Event-Related Brain Potentials/Fields i: A Critical Tutorial Review. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostenveld, R.; Fries, P.; Maris, E.; Schoffelen, J.M. FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 2011, 156869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, F.; Delorme, A.; Nikulin, V.; Haufe, S. Identifying Good Practices for Detecting Inter-Regional Linear Functional Connectivity from EEG. NeuroImage 2023, 277, 120218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ERP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Factor | Direction of Effect | Test Statistic | p | η2 |

| P100 | Face Category | Robot > Human | F(1, 45) = 13.50 | <0.001 | 0.021 |

| Valence | — | ns | ns | ns | |

| N170 | Face Category | Robot > Human (Left Sites) a | F(1, 45) = 6.34 | 0.015 | 0.002 |

| Valence | — | ns | ns | ns | |

| P300 | Face Category | Robot > Human | F(1, 45) = 10.59 | 0.002 | 0.028 |

| Valence | Neutral > Happy | F(1, 45) = 7.80 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| P600 | Face Category | Human > Robot | F(1, 45) = 54.35 | <0.001 | 0.128 |

| Valence | Neutral > Happy b | F(1.86, 83.87) = 3.91 | 0.026 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pérez-Arenas, X.; Rivera-Rei, Á.A.; Huepe, D.; Soto, V. Do We View Robots as We Do Ourselves? Examining Robotic Face Processing Using EEG. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010009

Pérez-Arenas X, Rivera-Rei ÁA, Huepe D, Soto V. Do We View Robots as We Do Ourselves? Examining Robotic Face Processing Using EEG. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010009

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Arenas, Xaviera, Álvaro A. Rivera-Rei, David Huepe, and Vicente Soto. 2026. "Do We View Robots as We Do Ourselves? Examining Robotic Face Processing Using EEG" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010009

APA StylePérez-Arenas, X., Rivera-Rei, Á. A., Huepe, D., & Soto, V. (2026). Do We View Robots as We Do Ourselves? Examining Robotic Face Processing Using EEG. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010009