Language Learning as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention in Older Adults with (Past) Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Data Collection Procedures

2.3. Outcome Variables and Covariates

2.4. English Course

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

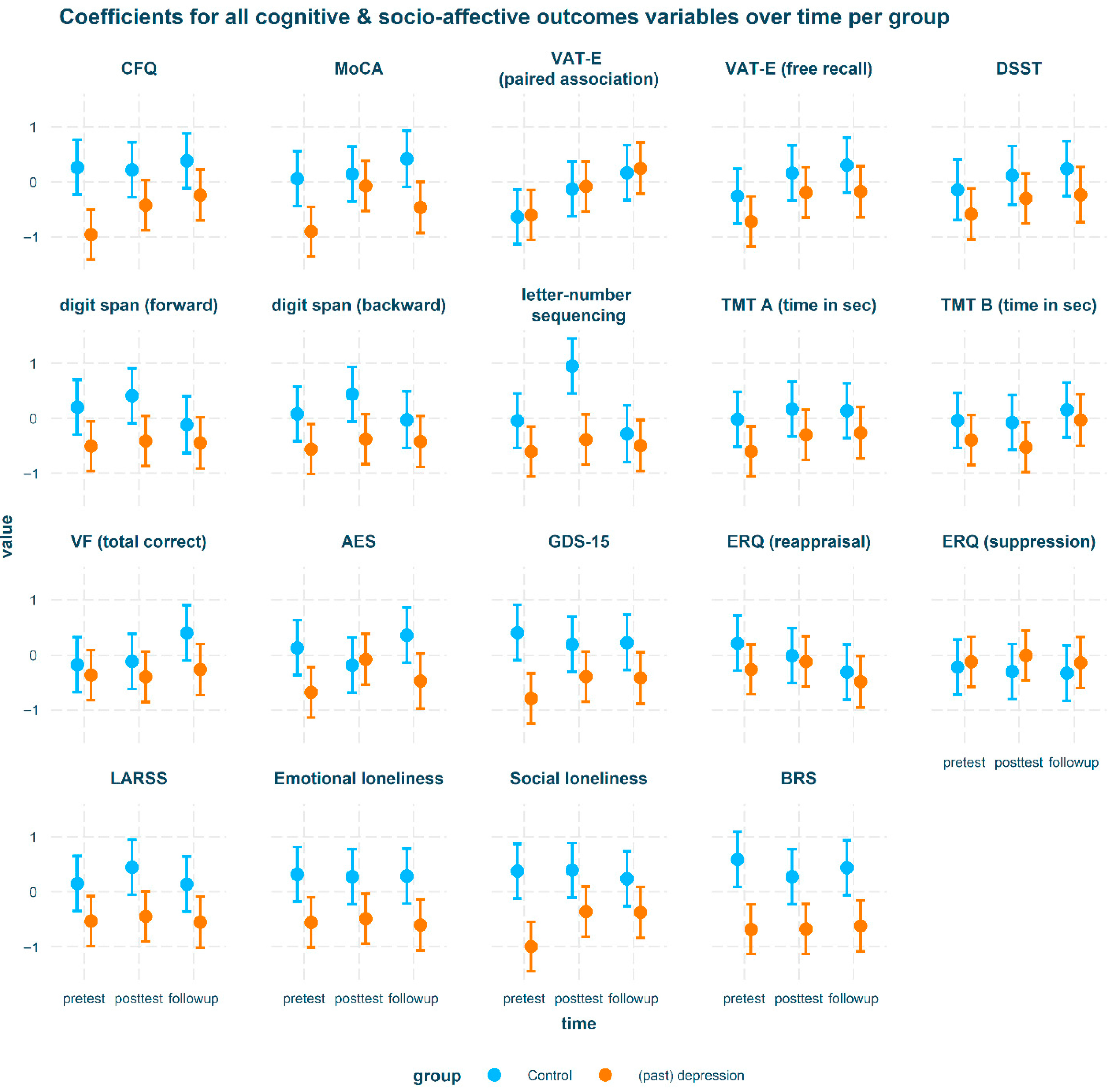

3.2. Intervention Outcomes

3.2.1. Association of Language Learning with Psychosocial Measures

3.2.2. Association of Language Learning with Cognitive Functioning

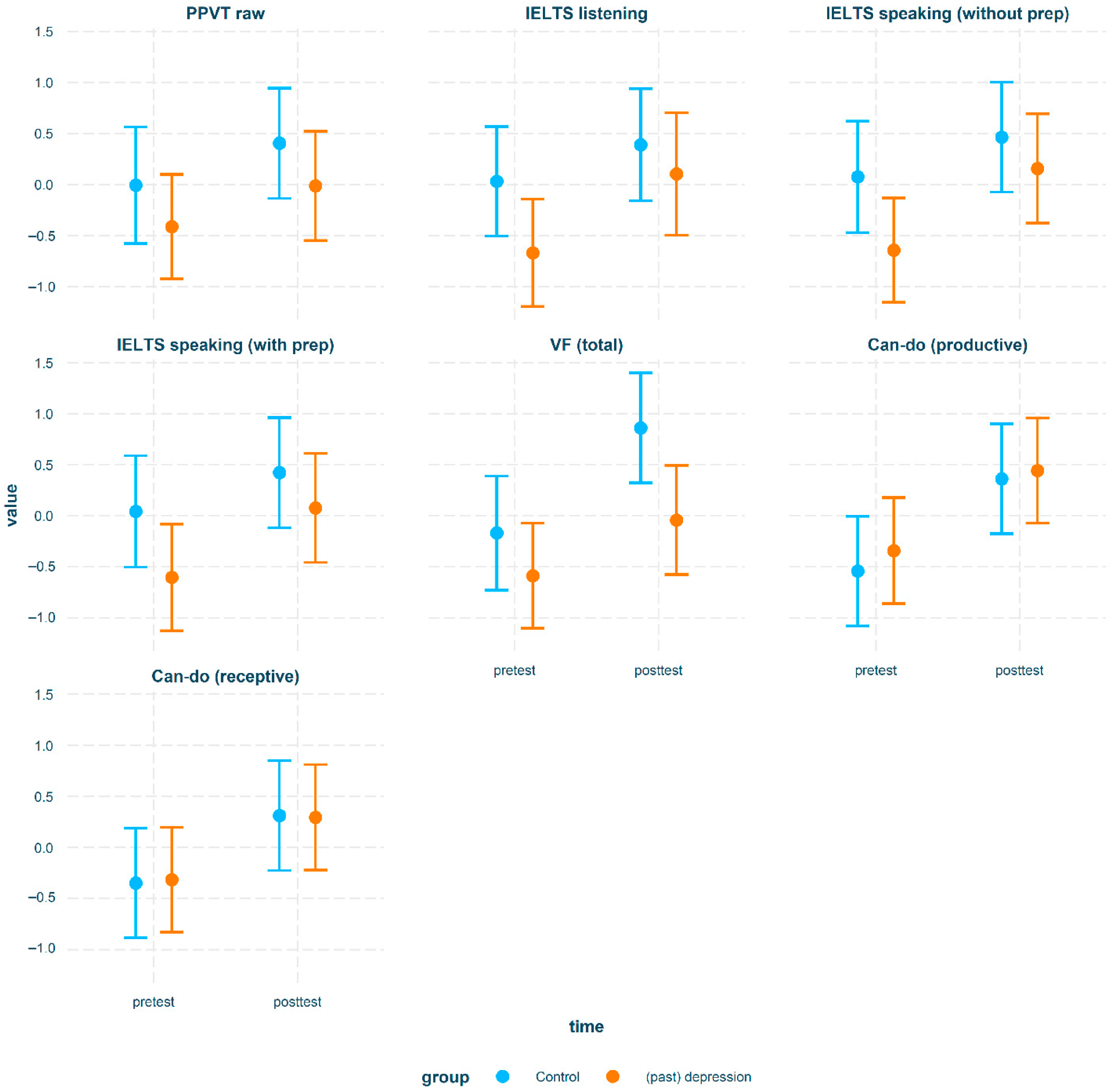

3.3. Associations of Language Learning with English Proficiency

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zenebe, Y.; Akele, B.; Selassie, M.W.; Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhong, X.; Peng, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Mai, N.; Huang, X.; Ning, Y. Longitudinal Association Between Cognition and Depression in Patients with Late-Life Depression: A Cross-Lagged Design Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 577058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, R.K.; Butters, M.A.; Mulsant, B.H.; Begley, A.E.; Zmuda, M.D.; Schoderbek, B.; Pollock, B.G.; Reynolds, C.F.; Becker, J.T. Persistence of Neuropsychologic Deficits in the Remitted State of Late-Life Depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáiz-Vázquez, O.; Gracia-García, P.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; Puente-Martínez, A.; Casado-Yusta, S.; Olaya, B.; Santabárbara, J. Depression as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Meta-Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motter, J.N.; Devanand, D.P.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Sneed, J.R. Computerized Cognitive Training for Major Depressive Disorder: What’s Next? Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neviani, F.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Mussi, C.; Triolo, F.; Toni, G.; Simoncini, E.; Tripi, F.; Menchetti, M.; Ferrari, S.; Ceresini, G.; et al. Physical exercise for late life depression: Effects on cognition and disability. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, D.C. Exercise for late-life depression? It depends. Lancet 2013, 382, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsumoto, D. Exploring Third-Age Foreign Language Learning from the Well-being Perspective: Work in Progress. SiSAL 2019, 10, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, M.; Gunasekera, G.M.; Wong, P.C.M. Foreign language training as cognitive therapy for age-related cognitive decline: A hypothesis for future research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2689–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, T.A.; Ware, J.; Fischer, C.E.; Craik, F.I.M.; Bialystok, E. Bilingualism as a contributor to cognitive reserve: Evidence from brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 2012, 48, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woumans, E.; Santens, P.; Sieben, A.; Versijpt, J.; Stevens, M.; Duyck, W. Bilingualism delays clinical manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2015, 18, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hell, J.G.; Dijkstra, T. Foreign language knowledge can influence native language performance in exclusively native contexts. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.M. How does bilingualism modify cognitive function? Attention to the mechanism. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 2022, 29, 1246–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.; Osterhout, L.; Kim, A. Neural correlates of second-language word learning: Minimal instruction produces rapid change. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, J.A.; Kates Rose, M.; Le, A.Y.; Spencer, K.A.; Goldstein, L.; Gubanova, A.; Lai, A.C.; Yossofzai, M.; Armstrong, S.E.M.; Bialystok, E. Improvement in executive function for older adults through smartphone apps: A randomized clinical trial comparing language learning and brain training. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2023, 30, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenninger, S.E.; Polz, S. Foreign language learning in the third age: A pilot feasibility study on cognitive, socio-affective and linguistic drivers and benefits in relation to previous bilingualism of the learner. J. Eur. Second. Lang. Assoc. 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B. Gao, Q., Zhou, J., Eds.; Cognitive, Mental and Social Benefits of Online Non-native Language Programs for Healthy Older People. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Supporting Everyday Life Activities; Springer International Publishing: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 12787, pp. 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.C.M.; Ou, J.; Pang, C.W.Y.; Zhang, L.; Tse, C.S.; Lam, L.C.W.; Antoniou, M. Language Training Leads to Global Cognitive Improvement in Older Adults: A Preliminary Study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2019, 62, 2411–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, R.; Nilsson, J.; Brehmer, Y.; Schmiedek, F.; Lövdén, M. Foreign language learning in older age does not improve memory or intelligence: Evidence from a randomized controlled study. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, J.A.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Teichmann, B.; Meyer, P. Foreign language learning can improve response inhibition in individuals with lower baseline cognition: Results from a randomized controlled superiority trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1123185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, C.; Damnee, S.; Djabelkhir, L.; Cristancho, V.; Wu, Y.-H.; Benovici, J.; Pino, M.; Rigaud, A.-S. Maintaining Cognitive Functioning in Healthy Seniors with a Technology-Based Foreign Language Program: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliesch, M.; Pfenninger, S.E.; Wieling, M.; Stark, E.; Meyer, M. Cognitive benefits of learning additional languages in old adulthood? Insights from an intensive longitudinal intervention study. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 43, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.C.M.; Ou, J.; Pang, C.W.Y.; Zhang, L.; Tse, C.S.; Lam, L.C.W.; Antoniou, M. Foreign language learning as potential treatment for mild cognitive impairment. Hong Kong Med. J. 2019, 25, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Keijzer, M.; Brouwer, J.; van der Berg, F.; van den Ploeg, M. Experimental methods to study late-life language learning. In The Routledge Handbook of Experimental Linguistics, 1st ed.; Zufferey, S., Gygax, P., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2023; pp. 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.; van den Berg, F.; Knooihuizen, R.; Loerts, H.; Keijzer, M. The effects of language learning on cognitive functioning and psychosocial well-being in cognitively healthy older adults: A semi-blind randomized controlled trial. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2025, 32, 270–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmand, B.A.; Bakker, D.; Saan, R.J.; Louman, J. De Nederlandse Leestest voor Volwassenen: Een maat voor het premorbide intelligentieniveau. [The Dutch Adult Reading Test: A measure of premorbid intelligence.]. TGG 1991, 22, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sikkes, S.A.M.; de Lange-de Klerk, E.S.M.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Gillissen, F.; Romkes, R.; Knol, D.L.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J.; Scheltens, P. A new informant-based questionnaire for instrumental activities of daily living in dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012, 8, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, N.; Leach, L.; Murphy, K.J. A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores: Re-examination of MoCA cutoff scores. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijmeijer, S.E.; Van Tol, M.-J.; Aleman, A.; Keijzer, M. Foreign Language Learning as Cognitive Training to Prevent Old Age Disorders? Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Language Training vs. Musical Training and Social Interaction in Elderly with Subjective Cognitive Decline. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 550180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M. Trail Making Test. Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Pearson: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S.R.A.; De Jonge, J.F.M. Visuele Associatietest—Extended: Handleiding; Hogrefe Uitgevers BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; FitzGerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. SCID-5-S Gestructureerd Klinisch Interview voor DSM-5 Syndroomstoornissen. Nederlandse Vertaling van Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® Disorders—Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV), First Edition, en User’s Guide to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® Disorders–Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV), First Edition en Delen van de Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® DisordersResearch Version (SCID-5-RV); Boom: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gierveld, J.D.J.; Tilburg, T.V. A 6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness: Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Res. Aging 2006, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consten, C.P. Measuring Resilience with the Brief Resilience Scale: Factor Structure, Reliability and Validity of the Dutch Version of the BRS (BRSnl). Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2016. Available online: https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/70095 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Marin, R.S.; Biedrzycki, R.C.; Firinciogullari, S. Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psych. Res. 1991, 38, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raes, F.; Bijttebier, P. Leuven Adaptation of the Rumination on Sadness Scale (LARSS). Gedragstherapie 2012, 45, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, D.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed.; (PPVTTM-4); Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.2.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Rencher, A.C.; Christensen, W.F. Methods of Multivariate Analysis: Rencher/Methods; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenth, R.V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, Version 1.8.4.-1. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Long, J.A. Interactions: Comprehensive, User-Friendly Toolkit for Probing Interactions, Version 1.1.5. 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=interactions (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P.; Makowski, D. performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. When Can You Safely Ignore Multicollinearity. Available online: https://statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- De Jong Gierveld, J.; Van Tilburg, T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Uchino, B.N.; Wethington, E. Loneliness and Health in Older Adults: A Mini-Review and Synthesis. Gerontology 2016, 62, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holvast, F.; Burger, H.; de Waal, M.M.W.; van Marwijk, H.W.J.; Comijs, H.C.; Verhaak, P.F.M. Loneliness is associated with poor prognosis in late-life depression: Longitudinal analysis of the Netherlands study of depression in older persons. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 185, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Mueller, C.; Shetty, H.; Perera, G.; Stewart, R. Predictors of mortality in people with late-life depression: A retrospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, H.W.; Stek, M.L.; Huisman, M.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Naarding, P.; Collard, R.M.; van der Mast, R.C.; Kok, R.M.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Comijs, H.C. A Six-Year Prospective Study of the Prognosis and Predictors in Patients with Late-Life Depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psych. 2018, 26, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstmeier, S.; Verena Thoma, M.; Maercker, A. Motivational reserve: The role of motivational processes in cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. In Multiple Pathways of Cognitive Aging: Motivational and Contextual Influences, 1st ed.; Sedek, G., Hess, T., Touron, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 128–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbrey, A.C.; Laidlaw, K.; Cassidy-Eagle, E.; Thompson, L.W.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Late-Life Depression: Evidence, Issues, and Recommendations. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2022, 29, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatar, Z.Z.; Moore, R.C.; Palmer, B.W.; Thompson, W.K.; Jeste, D.V. Cognitive Complaints Correlate with Depression Rather Than Concurrent Objective Cognitive Impairment in the Successful Aging Evaluation Baseline Sample. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2014, 27, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliesch, M.; Pfenninger, S.E. Cognitive and Socioaffective Predictors of L2 Microdevelopment in Late Adulthood: A Longitudinal Intervention Study. Mod. Lang. J. 2021, 105, 237–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, M.; Keijzer, M.; Lowie, W. Language pedagogies and late-life language learning proficiency. Int. Rev. Appl. Ling. Lang. Teach. 2023, 63, 303–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Morley, A.; Young, B.; Waheed, W.; Small, N.; Bower, P. Factors affecting recruitment into depression trials: Systematic review, meta-synthesis and conceptual framework. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 172, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (Sub) Domain | Measure | Reference | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | |||

| Cognitive flexibility | Trail Making Test B (TMT-B) | [31] | Seconds to complete |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) digit-symbol substitution | [32] | Number of symbols in 120 s (0–133) | |

| WAIS-IV letter-number sequencing (Please note:. Also indexes working memory) | [32] | Total correctly recalled sequences (0–21) | |

| Episodic memory | Visual Association Task-Extended (VAT-E) paired association subscale | [33] | Number of correctly recalled images (1–24) |

| VAT-E free recall subscale | [33] | Number of correctly recalled images (1–48) | |

| Global cognition | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | [34] | Overall score (0–30) |

| Subjective cognitive functioning | Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) | [35] | Degree of experienced cognitive failures (0–100) |

| Attention/processing speed | Trail Making Task A (TMT-A) | [31] | Seconds to complete |

| Working memory | WAIS-IV digit span forward | [32] | Total correctly recalled sequences (0–12) |

| WAIS-IV digit span backward | [32] | Total correctly recalled sequences (0–12) | |

| Executive functioning/verbal fluency | Phonetic verbal fluency (DAT, KOM, or PGR) | Total correctly named words | |

| Psychosocial well-being | |||

| Depression symptoms | Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version (GDS-15) | [36] | Depression severity (0–15) |

| Psychiatric disorders | Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-V (SCID-5) | [37] | Presence of current or past psychiatric disorders |

| Loneliness | De Jong-Gierveld 6-item loneliness scale | [38] | Social and emotional loneliness (0–3) |

| Resilience | Brief Resilience Scale | Original: [39] Translation: [40] | Ability to bounce back after setbacks and stressful life events (1–5) |

| Apathy | Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) | [41] | Total score (18–72) |

| Rumination | Leuven Adaptation of the Rumination on Sadness | [42] | Total score (21–105) |

| English proficiency | |||

| Lexical access | English Phonetic Verbal Fluency (PRW, CFL, FAS) | Total correctly named words | |

| Vocabulary size | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Naming Test (PPVT-4) | [43] | Raw score (ceiling item minus number of incorrect answers) (0–228) |

| Speaking proficiency | International English Language Testing System (IELTS) speaking test | Overall score on spontaneous (0–9) and prepared speech (0–9) | |

| Listening proficiency | International English Language Testing System (IELTS) listening test | Overall summed score on listening tests (0–20) | |

| Control Group Not Depressed in the Past 25 Years or Longer (n = 15) | Participants with Current Depression or Depression in the Past 25 Years (n = 19) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD)/n % | M (SD)/n % | ||

| Age (years) | 70.1 (3.8) | 69.7 (2.9) | n.s. |

| Gender Women Men | 9 (60%) 5 (40%) | 15 (79%) 4 (21%) | n.s. |

| Current working situation | Retired: 11 (73.3%) Volunteering: 1 (6.7%) Part-time: 1 (6.7%) Informal care: 1 (6.7%) Self-employed: 1 (6.7%) | Retired 17: (89.5%) Volunteering: 1 (5.3%) Part-time: 1 (5.3%) | n.s. |

| MoCA (at screening) | 26.9 (1.2) | 25.1 (2.4) | <0.05 * |

| Cognitive reserve | 144.7 (19.7) | 131.2 (13.5) | <0.05 * |

| Premorbid intelligence | 92.5 (8.5) | 94.0 (8.2) | n.s. |

| Number of participants with GDS ≥ 5 OR current major depressive disorder according to DSM-V criteria at screening | 0 | 9 | <0.01 ** |

| Average number of hours per week spent on intervention (4.5 h requested by researchers) | 5.7 (4.3) | 5.2 (2) |

| Control Group (n = 15) | Participants with Current or Past Depression (n = 19) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Measures | Pretest | Posttest | Followup | Pretest | Posttest | Followup |

| CFQ | 31.40 (11.68) | 32.20 (8.13) | 30.33 (10.41) | 46.11 (13.43) | 39.89 (8.37) | 37.56 (12.21) |

| MoCA | 26.93 (1.87) | 27.07 (2.25) | 27.71 (1.14) | 24.95 (2.46) | 26.63 (1.67) | 25.83 (1.69) |

| VAT-E (paired association) | 14.33 (4.82) | 17.33 (6.26) | 19.07 (5.81) | 14.58 (6.21) | 17.63 (6.95) | 19.72 (4.96) |

| VAT-E (free recall) | 24.93 (7.52) | 28.53 (9.36) | 29.67 (10.33) | 20.89 (8.03) | 25.42 (7.81) | 25.61 (8.68) |

| DSST | 60.67 (7.52) | 63.38 (9.12) | 64.67 (9.42) | 54.06 (14.98) | 57.68 (17.58) | 58.33 (13.96) |

| Digit span forward | 7.20 (2.18) | 7.60 (2.69) | 6.57 (2.03) | 5.74 (1.41) | 5.89 (1.73) | 5.83 (2.04) |

| Digit span backward | 7.60 (1.92) | 8.27 (2.31) | 7.43 (1.79) | 6.37 (1.38) | 6.68 (1.63) | 6.61 (2.20) |

| Letter-number sequencing | 10.93 (2.87) | 13.53 (3.56) | 10.36 (1.86) | 9.47 (1.84) | 10.00 (2.00) | 9.72 (1.71) |

| TMT-A | 38.73 (8.22) | 36.93 (6.49) | 37.40 (7.83) | 44.79 (12.49) | 41.84 (12.02) | 41.39 (12.22) |

| TMT-B | 78.53 (19.46) | 79.93 (26.33) | 74.53 (19.71) | 87.26 (24.49) | 90.95 (35.68) | 78.50 (16.22) |

| Dutch verbal fluency | 46.53 (9.66) | 47.00 (9.65) | 52.40 (12.00) | 44.58 (10.30) | 44.05 (11.79) | 45.56 (9.92) |

| Psychosocial well-being | Pretest | Posttest | Followup | Pretest | Posttest | Followup |

| AES | 26.2 (3.86) | 28.2 (5.39) | 25.0 (4.90) | 31.0 (6.77) | 27.5 (5.59) | 30.0 (7.25) |

| GDS-15 | 0.40 (1.30) | 1.13 (2.56) | 1.07 (2.81) | 4.21 (3.55) | 3.00 (3.46) | 3.06 (3.24) |

| ERQ (cognitive reappraisal) | 28.27 (7.27) | 26.53 (8.87) | 24.33 (8.57) | 24.95 (5.03) | 25.84 (5.89) | 23.28 (7.16) |

| ERQ (expressive suppression) | 13.00 (4.11) | 13.47 (4.16) | 13.67 (6.85) | 12.47 (5.33) | 12.00 (5.12) | 12.61 (4.17) |

| LARSS | 32.67 (14.52) | 28.27 (15.41) | 33.33 (16.47) | 43.58 (14.49) | 42.47 (14.01) | 44.06 (16.46) |

| Emotional loneliness | 0.20 (0.77) | 0.27 (0.80) | 0.27 (0.80) | 1.11 (1.15) | 1.05 (1.08) | 1.17 (1.04) |

| Social loneliness | 0.27 (0.59) | 0.27 (0.80) | 0.47 (1.06) | 1.89 (1.33) | 1.16 (0.90) | 1.17 (1.34) |

| BRS | 3.91 (0.43) | 3.69 (0.69) | 3.79 (0.62) | 3.08 (0.55) | 3.07 (0.51) | 3.11 (0.56) |

| Language outcomes | Pretest | Posttest | Followup | Pretest | Posttest | Followup |

| English verbal fluency | 26.62 (5.77) | 36.27 (11.18) | N/A | 23.47 (8.02) | 28.69 (7.17) | N/A |

| PPVT | 153.25 (17.72) | 160.60 (15.01) | N/A | 144.32 (25.93) | 153.44 (25.30) | N/A |

| IELTS speaking (without preparation) | 5.07 (1.21) | 5.53 (1.46) | N/A | 4.16 (1.34) | 5.25 (1.00) | N/A |

| IELTS speaking (with preparation) | 5.64 (0.93) | 6.07 (1.53) | N/A | 4.94 (1.30) | 5.75 (1.06) | N/A |

| IELTS Listening proficiency | 15.13 (3.66) | 16.50 (3.08) | N/A | 13.06 (3.90) | 16.00 (3.32) | N/A |

| Can-do (productive) | 3.09 (0.46) | 3.70 (0.30) | N/A | 3.25 (0.83) | 3.80 (0.79) | N/A |

| Can-do (receptive) | 3.55 (0.58) | 4.01 (0.41) | N/A | 3.62 (0.89) | 4.03 (0.77) | N/A |

| Difference Between Intervention Groups per Time-Point for Psychosocial and Cognitive Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Group | Variable | est | SE | t | p | d |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | AES | 0.81 | 0.33 | 2.47 | <0.05 | 0.89 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | BRS | 1.27 | 0.33 | 3.89 | <0.001 | 1.41 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | CFQ | 1.22 | 0.33 | 3.74 | <0.001 | 1.35 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | Digit span (forward) | 0.71 | 0.33 | 2.16 | <0.05 | 0.78 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | GDS | 1.19 | 0.33 | 3.65 | <0.001 | 1.32 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | LARSS | 0.69 | 0.33 | 2.1 | <0.05 | 0.76 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | loneliness (emotional) | 0.88 | 0.33 | 2.68 | <0.01 | 0.97 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | loneliness (social) | 1.37 | 0.33 | 4.19 | <0.001 | 1.52 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | MoCA | 0.96 | 0.33 | 2.95 | <0.01 | 1.07 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | BRS | 0.95 | 0.33 | 2.91 | <0.01 | 1.05 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | CFQ | 0.64 | 0.33 | 1.97 | <0.05 | 0.71 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | Digit span (backward) | 0.82 | 0.33 | 2.5 | <0.05 | 0.9 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | Digit span (forward) | 0.82 | 0.33 | 2.52 | <0.05 | 0.91 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | LARSS | 0.89 | 0.33 | 2.72 | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | letter-number seq | 1.34 | 0.33 | 4.09 | <0.001 | 1.48 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | loneliness (emotional) | 0.76 | 0.33 | 2.33 | <0.05 | 0.84 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | loneliness (social) | 0.75 | 0.33 | 2.3 | <0.05 | 0.83 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | AES | 0.83 | 0.34 | 2.42 | <0.05 | 0.92 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | BRS | 1.06 | 0.33 | 3.2 | <0.01 | 1.17 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | LARSS | 0.69 | 0.33 | 2.09 | <0.05 | 0.77 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | loneliness (emotional) | 0.89 | 0.33 | 2.69 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | MoCA | 0.88 | 0.34 | 2.63 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| control—(past) depression | followup | VF | 0.66 | 0.33 | 2.01 | <0.05 | 0.74 |

| Differences over time within groups for psychosocial and cognitive outcomes | |||||||

| Contrast | Group | Variable | est | SE | t | p | d |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | MoCA | −0.83 | 0.29 | −2.83 | <0.01 | −0.92 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | AES | −0.59 | 0.3 | −2 | <0.05 | −0.66 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | Loneliness (social) | −0.64 | 0.29 | −2.17 | <0.05 | −0.7 |

| pretest—followup | (past) depression | CFQ | −0.72 | 0.3 | −2.42 | <0.05 | −0.8 |

| pretest—followup | (past) depression | VAT-E (paired assoc) | −0.85 | 0.3 | −2.86 | <0.01 | −0.94 |

| pretest—followup | (past) depression | Loneliness (social) | −0.62 | 0.3 | −2.09 | <0.05 | −0.69 |

| pretest—posttest | control | Letter-number seq | −1 | 0.33 | −3.02 | <0.01 | −1.1 |

| pretest—followup | control | VAT-E (paired assoc) | −0.8 | 0.33 | −2.43 | <0.05 | −0.89 |

| posttest—followup | control | Letter-number seq | 1.23 | 0.34 | 3.67 | <0.001 | 1.36 |

| Difference over time between intervention groups for psychosocial and cognitive outcomes | |||||||

| Time (pairwise) | Group (pairwise) | Variable | est | SE | t | p | d |

| pretest—posttest | control—(past) depression | AES | 0.91 | 0.44 | 2.05 | <0.05 | 1.01 |

| posttest—followup | control—(past) depression | AES | −0.93 | 0.46 | −2.04 | <0.05 | −1.03 |

| posttest—followup | control—(past) depression | Letter-number seq | 1.12 | 0.45 | 2.5 | <0.05 | 1.24 |

| Difference between groups per time-point for English proficiency outcomes | |||||||

| Contrast | Time | Variable | est | SE | t | p | d |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | IELTS (listening) | 0.7 | 0.33 | 2.16 | <0.05 | 0.93 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | IELTS (speaking w/o prep) | 0.72 | 0.32 | 2.22 | <0.05 | 0.95 |

| control—(past) depression | pretest | IELTS (speaking with prep) | 0.65 | 0.33 | 1.98 | <0.05 | 0.86 |

| control—(past) depression | posttest | VF | 0.9 | 0.33 | 2.75 | <0.01 | 1.2 |

| Differences over time within group for English proficiency outcomes | |||||||

| Contrast | Group | Variable | est | SE | t | p | d |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | IELTS (listening) | −0.77 | 0.29 | −2.63 | <0.01 | −1.03 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | IELTS (speaking w/o prep) | −0.8 | 0.26 | −3.12 | <0.01 | −1.06 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | IELTS (speaking with prep) | −0.68 | 0.26 | −2.61 | <0.01 | −0.9 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | VF | −0.54 | 0.26 | −2.12 | <0.05 | −0.72 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | Can-do (productive) | −0.79 | 0.25 | −3.16 | <0.01 | −1.04 |

| pretest—posttest | (past) depression | Can-do (receptive) | −0.61 | 0.24 | −2.5 | <0.05 | −0.81 |

| pretest—posttest | control | VF | −1.03 | 0.29 | −3.59 | <0.001 | −1.36 |

| pretest—posttest | control | Can-do (productive) | −0.9 | 0.28 | −3.28 | <0.01 | −1.2 |

| pretest—posttest | control | Can-do (receptive) | −0.66 | 0.28 | −2.4 | <0.05 | −0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brouwer, J.; van den Berg, F.; Knooihuizen, R.; Loerts, H.; Keijzer, M. Language Learning as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention in Older Adults with (Past) Depression. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090991

Brouwer J, van den Berg F, Knooihuizen R, Loerts H, Keijzer M. Language Learning as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention in Older Adults with (Past) Depression. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090991

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrouwer, Jelle, Floor van den Berg, Remco Knooihuizen, Hanneke Loerts, and Merel Keijzer. 2025. "Language Learning as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention in Older Adults with (Past) Depression" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090991

APA StyleBrouwer, J., van den Berg, F., Knooihuizen, R., Loerts, H., & Keijzer, M. (2025). Language Learning as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention in Older Adults with (Past) Depression. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090991