Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 417,152 Patients with Trial Sequential Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Extraction

2.3. Endpoints and Subgroup Analyses

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA)

3. Results

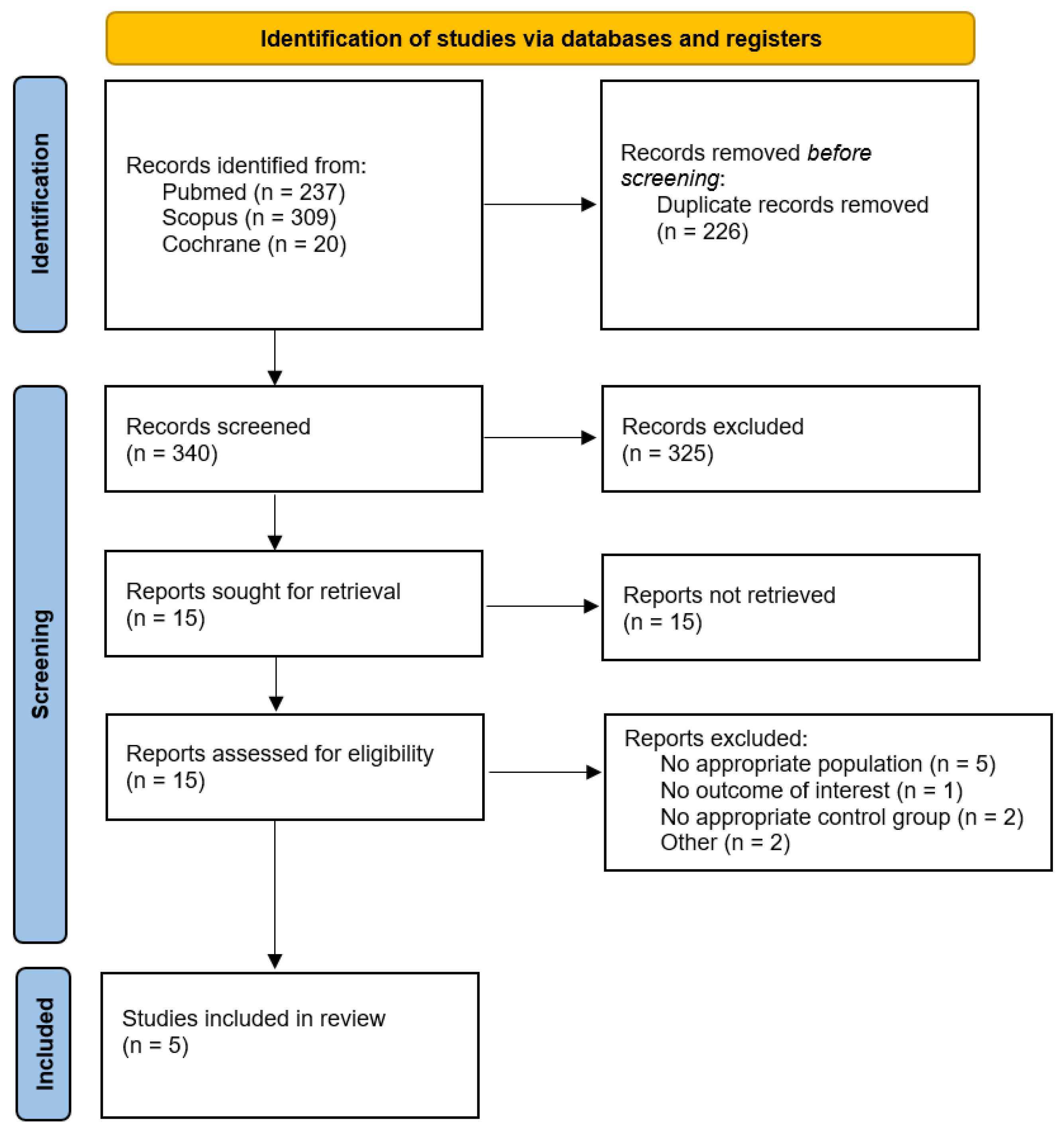

3.1. Study Selection and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Pooled Analyses of All Included Studies

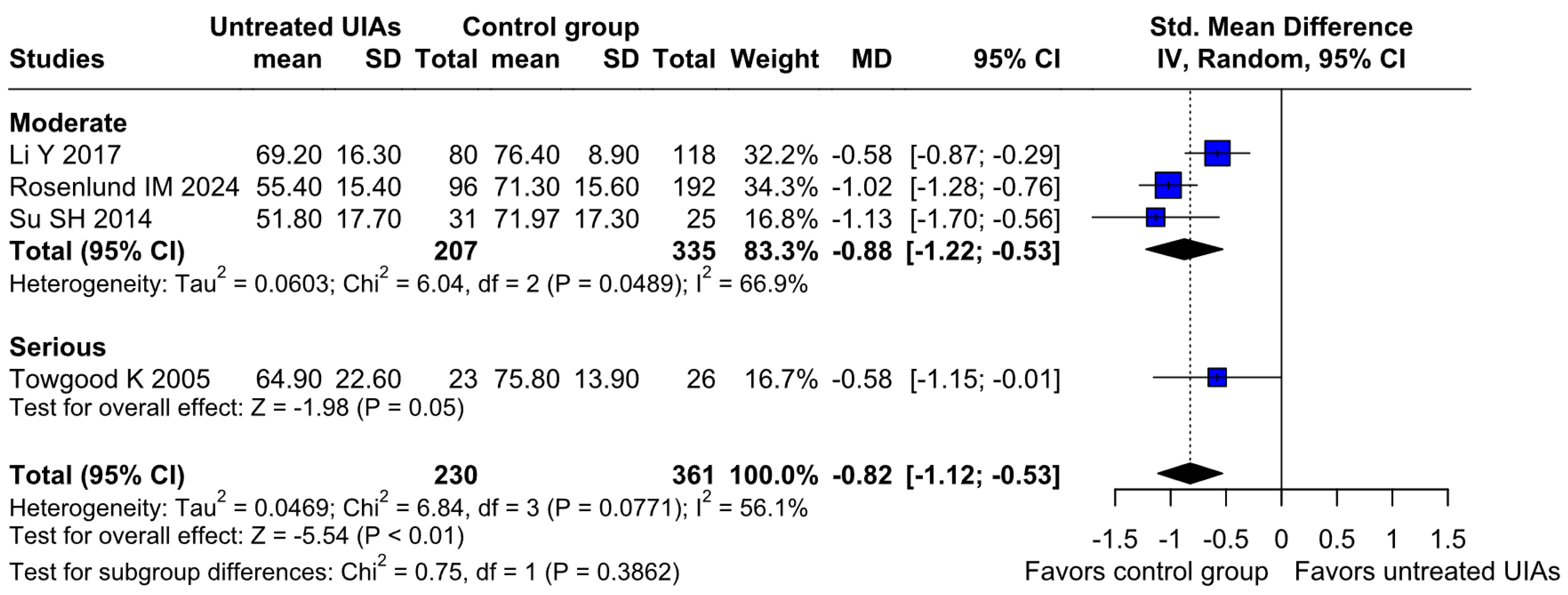

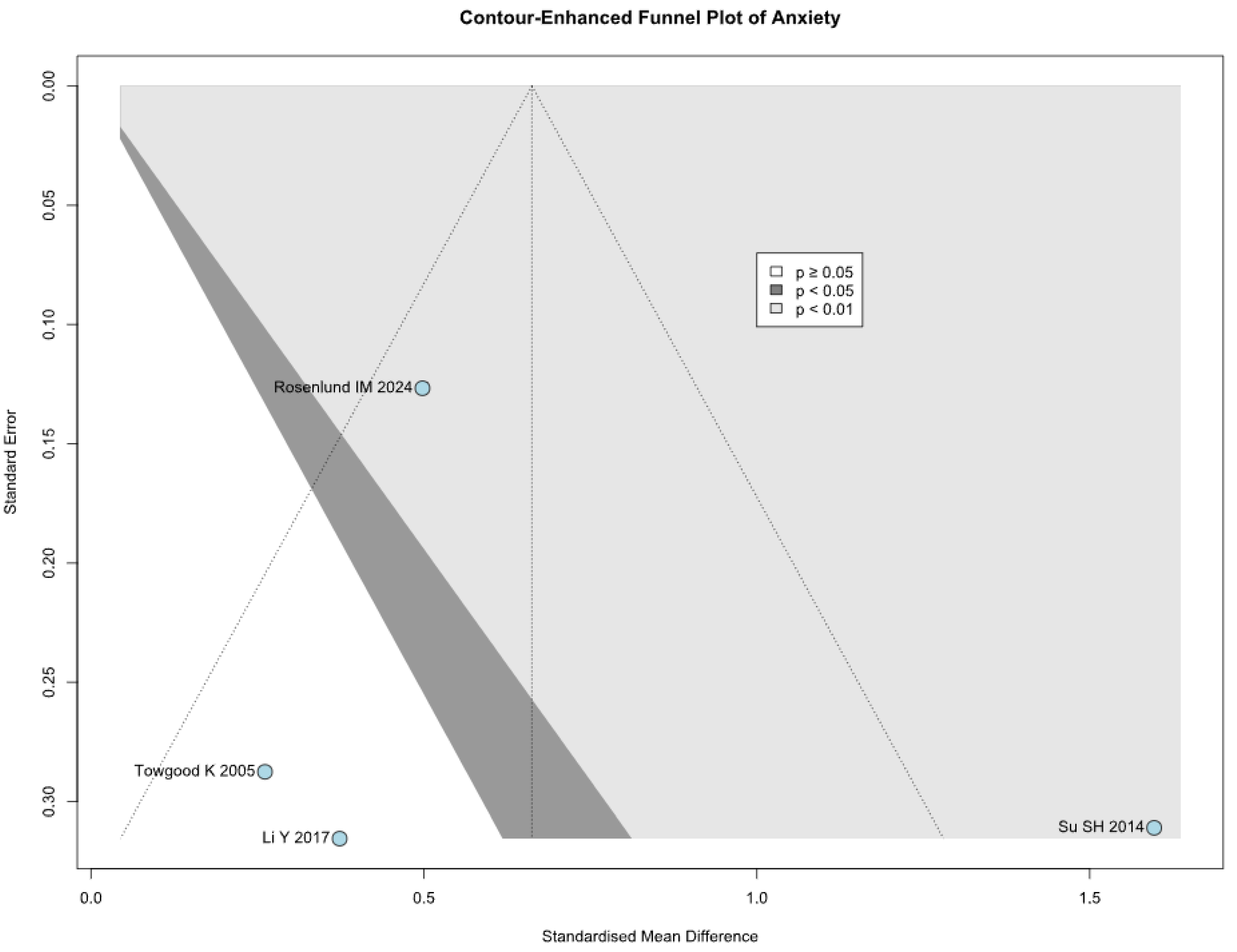

3.2.1. Anxiety

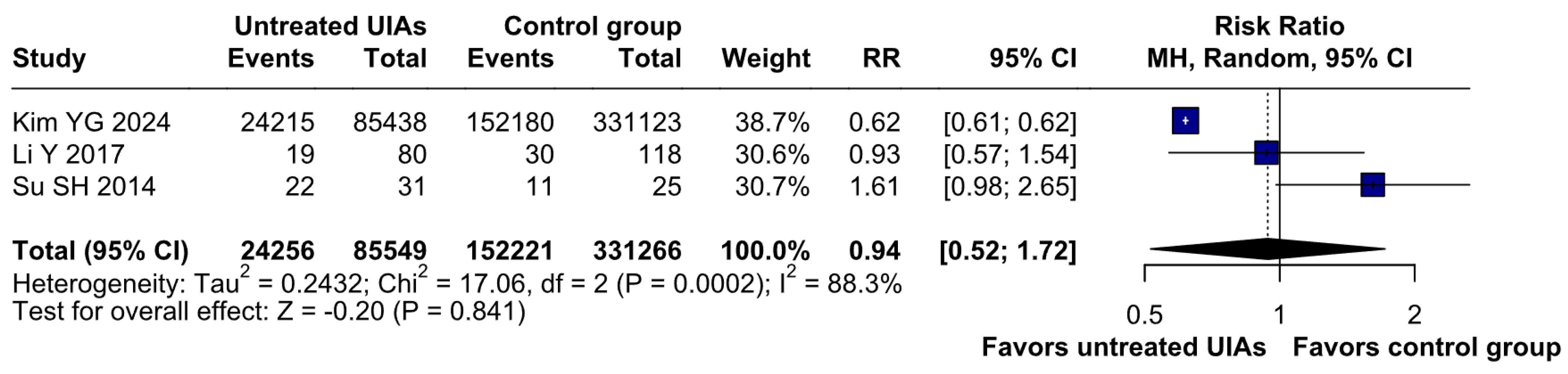

3.2.2. Depression

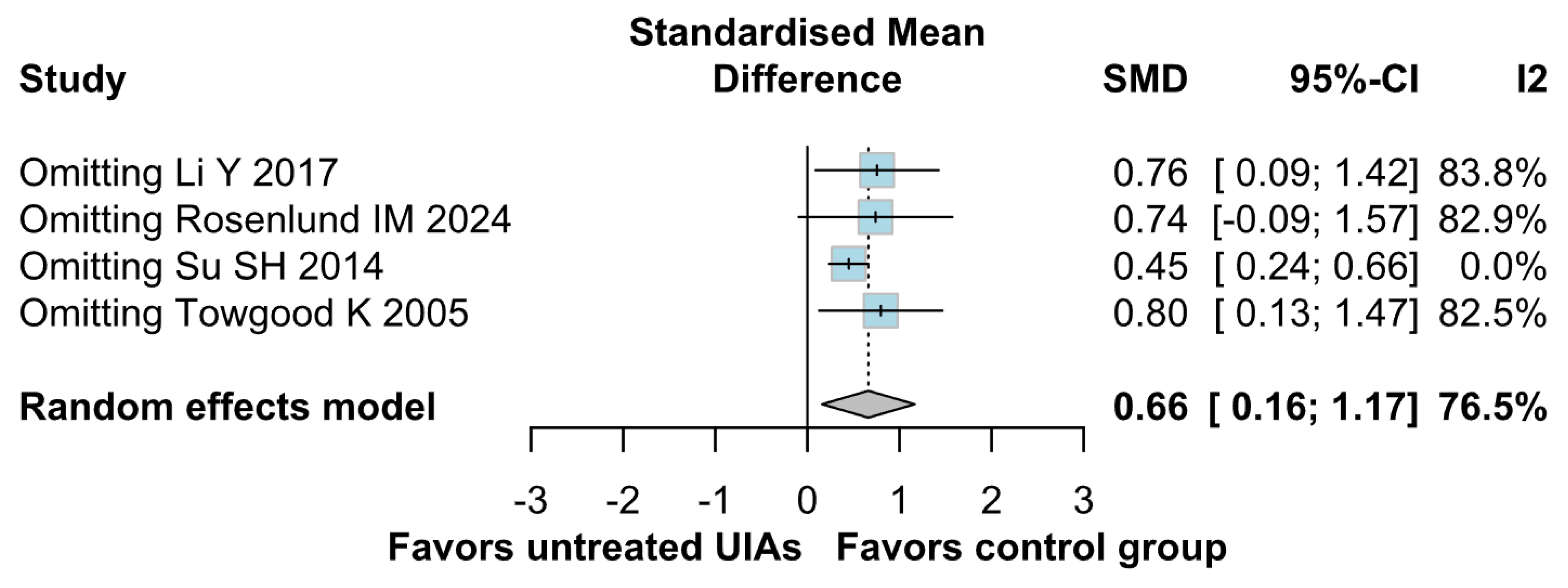

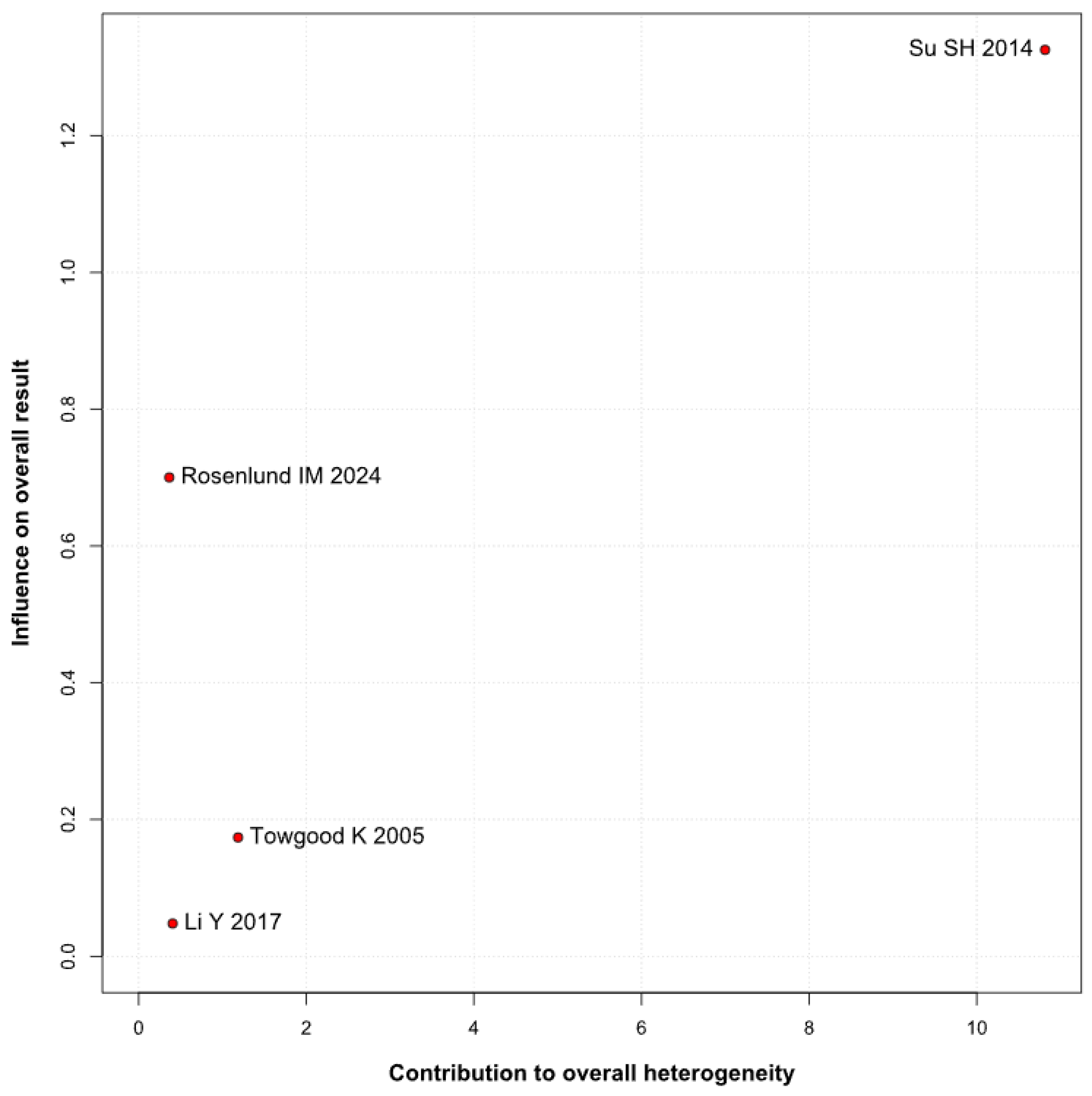

3.2.3. QoL

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

3.3.1. Risk of Bias

Anxiety

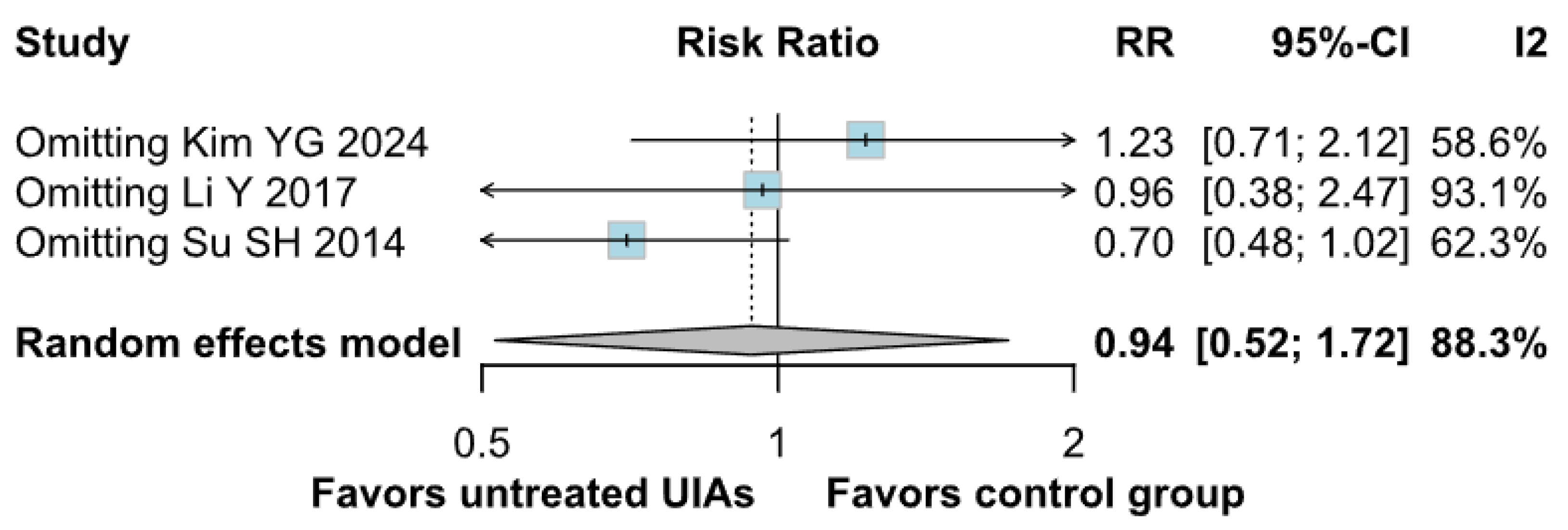

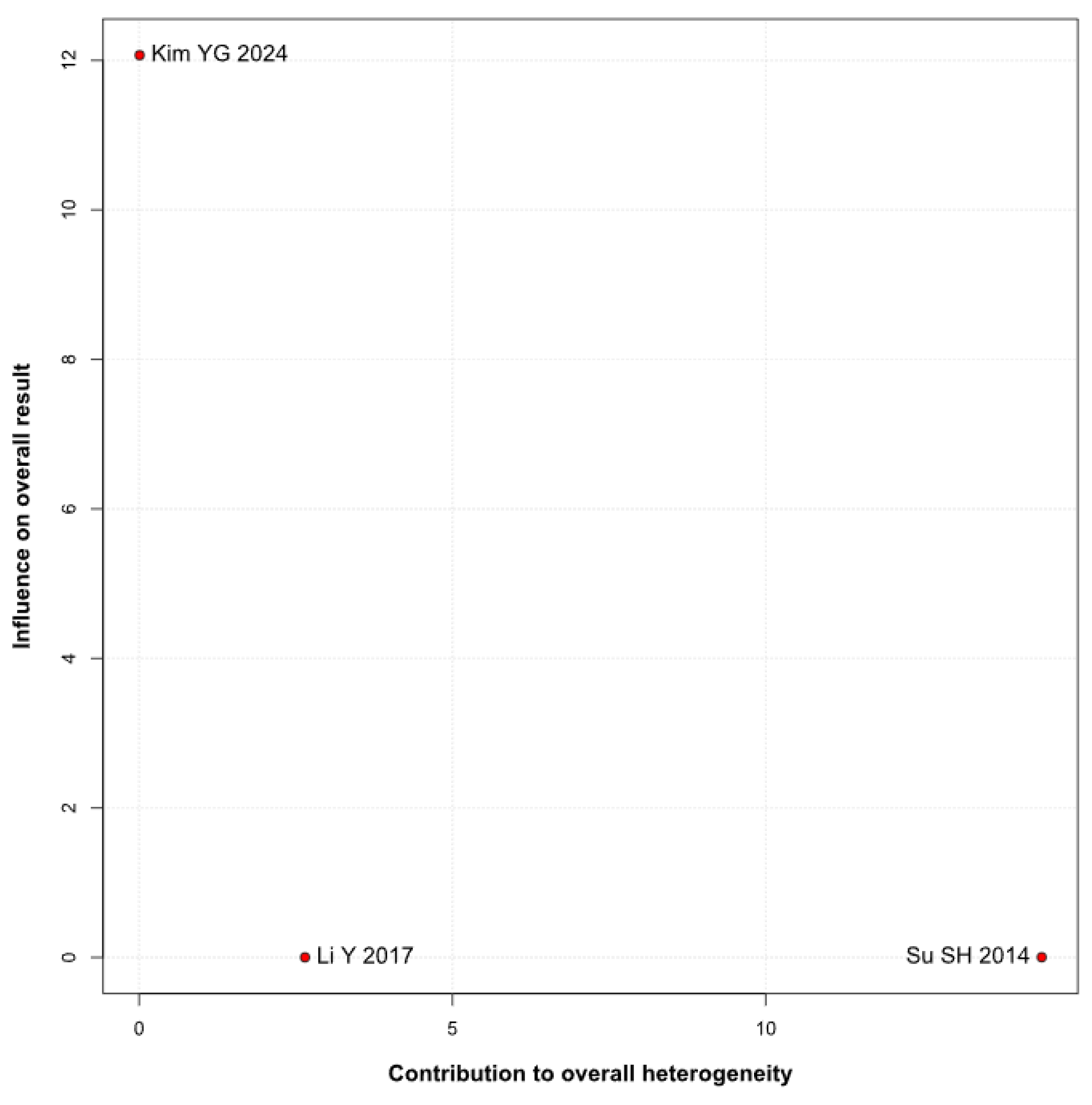

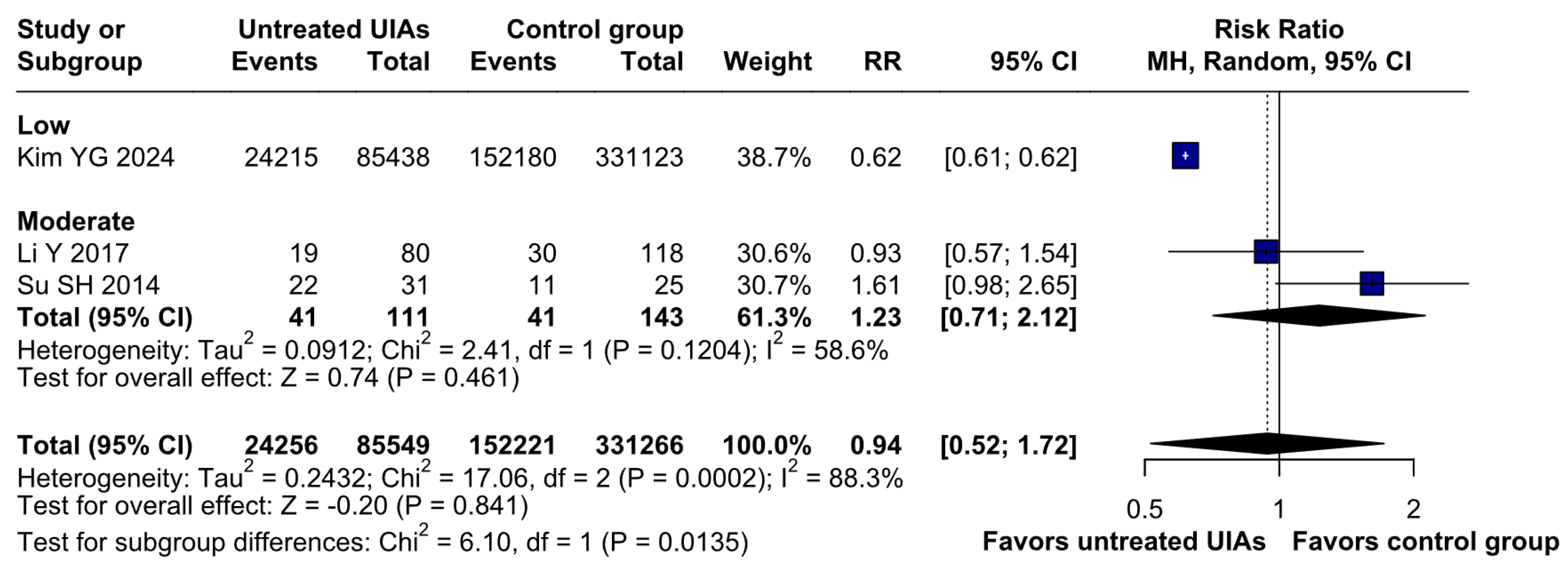

Depression

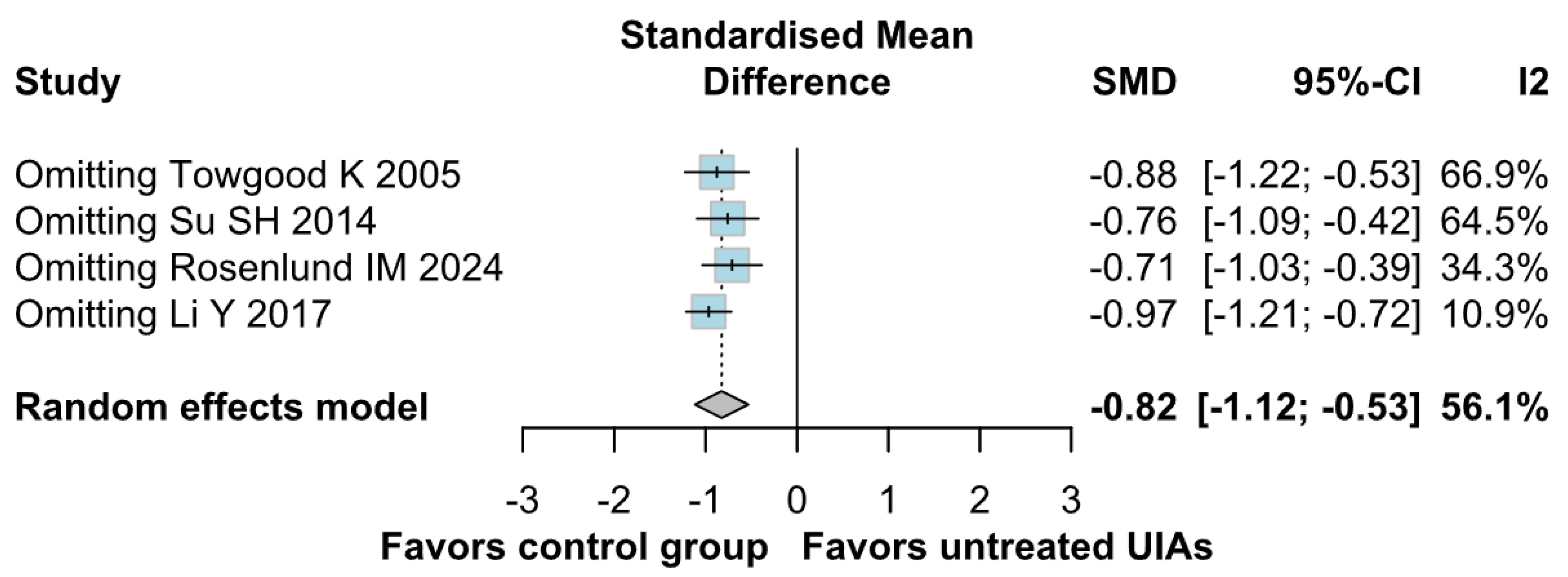

QoL

3.4. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Dai, W.; Zhang, J. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with a treated or untreated unruptured intracranial aneurysm. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 45, 223–226. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28778800/ (accessed on 31 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiebers, D.O.; Whisnant, J.P.; Huston, J., 3rd; Meissner, I.; Brown, R.D., Jr.; Piepgras, D.G.; Forbes, G.S.; Thielen, K.; Nichols, D.; O’Fallon, W.M.; et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003, 362, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; An, H.; Kim, G.E.; Lee, H.W.; Yang, N.R. Higher Risk of Mental Illness in Patients With Diagnosed and Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm: Findings From a Nationwide Cohort Study. Stroke 2024, 55, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towgood, K.; Ogden, J.A.; Mee, E. Psychosocial Effects of Harboring an Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 858–864. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Psychosocial-Effects-of-Harboring-an-Untreated-Towgood-Ogden/51a2b13dd704fe7e73df69fad4164b1b58c401cb#:~:text=A%20decrease%20in%20overall%20quality%20of%20life%20was,past%20or%20current%20fear%20about%20their%20untreated%20UIA (accessed on 31 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.-D.; Yu, J.-X.; Ma, Y.-J.; Xiang, S.-S.; Li, G.-L.; He, C.; Hu, P.; Zhang, H.-Q. Prevalence of and risk factors for anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms treated by endovascular intervention. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, A.; Pawlikowski, A.; Brand, C.; Schmitz, B.; Wirtz, C.R.; König, R.; Kapapa, T. Quality of life after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. World Neurosurg. 2019, 121, e54–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, A.; Trungu, S.; Raco, A. Clinical and Neuropsychological Outcome After Microsurgical and Endovascular Treatment of Ruptured and Unruptured Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms: A Single-Enter Experience. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2017, 124, 173–177, Erratum in Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2017, 124, E2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39546-3_50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Wada, K.; Otani, N.; Tomiyama, A.; Toyooka, T.; Tomura, S.; Takeuchi, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakao, Y.; Arai, H. Long-Term Neurological and Radiological Results of Consecutive 63 Unruptured Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms Clipped via Lateral Supraorbital Keyhole Minicraniotomy. Oper. Neurosurg. 2018, 14, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzon-Muvdi, T.; Yang, W.; Luksik, A.S.; Ruiz-Valls, A.; Tamargo, R.J.; Caplan, J.; Tamargo, R.J. Postoperative Delayed Paradoxical Depression After Uncomplicated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2017, 99, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenz, H.; Wenz, R.; Maros, M.E.; Groden, C.; Schmieder, K.; Fontana, J. The neglected need for psychological intervention in patients sufering from incidentally discovered intracranial aneurysms. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 143, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wostrack, M.; Friedrich, B.; Hammer, K.; Harmening, K.; Stankewitz, A.; Ringel, F.; Shiban, E.; Boeckh-Behrens, T.; Prothmann, S.; Zimmer, C.; et al. Hippocampal damage and afective disorders after treatment of cerebral aneurysms. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 2128–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, K.; Dombek, S.; Martens, T.; Köppen, J.; Westphal, M.; Regelsberger, J. Neuropsychological assessments in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, perimesencephalic SAH, and incidental aneurysms. Neurosurg. Rev. 2014, 37, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, Y.; Ogasawara, K.; Kashimura, H.; Otawara, Y.; Kakino, S.; Sugawara, A.; Ogawa, A. Cognitive function and anxiety before and after surgery for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms in elderly patients. World Neurosurg. 2010, 73, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, S.; Nishi, T.; Koga, K.; Goto, T.; Kaji, M.; Muta, D.; Kuratsu, J.I.; Fujioka, S. Improvement of quality of life in patients surgically treated for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 78, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, S.; Nishi, T.; Koga, K.; Goto, T.; Muta, D.; Kuratsu, J.; Fujioka, S. Postoperative quality of life of patients treated for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 107, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, O.; Eloqayli, H.; Muller, T.B.; Unsgaard, G. Quality of life after treatment for incidental, unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir. 2006, 148, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilstra, E.H.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; van der Graaf, Y.; Sluzewski, M.; Groen, R.J.; Lo, R.T.H.; Tulleken, C.A.F. Quality of life after treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms by neurosurgical clipping or by embolisation with coils. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2004, 17, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otawara, Y.; Ogasawara, K.; Kubo, Y.; Tomitsuka, N.; Watanabe, M.; Ogawa, A.; Suzuki, M.; Yamadate, K. Anxiety before and after surgical repair in patients with asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Surg. Neurol. 2004, 62, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignacio, K.H.D.; Pascual, J.S.G.; Factor, S.J.V.; Khu, K.J.O. A meta-analysis on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Exposing critical treatment gaps. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 2077–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J. Hrsg. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023). Cochrane. 2023. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantel, N.; Haenszel, W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1959, 22, 719–748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hartung, J.; Knapp, G. On tests of the overall treatment effect in meta-analysis with normally distributed responses. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.; Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 2693–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Review Manager (RevMan). Version (Version Number 5.4.1); The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, (Version Date 5.4.1). Available online: https://login.cochrane.org/realms/cochrane/protocol/openid-connect/auth?client_id=revman-web&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Frevman.cochrane.org&response_type=code&scope=openid%20profile&nonce=eb80c11afc5cdbd9d7477a304b0e2d8d1fCTi4ZCm&state=4b27aa0c77fe23be03f9a149d8a0f32662EySAbKk&code_challenge=2WXnoug9mKggcZNhCy9MC7-flLyPpfFxcAYSFft-RsA&code_challenge_method=S256 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) [Computer Program], Version 0.9.5.10 Beta; The Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, The Capital Region, Copenhagen University Hospital–Rigshospitalet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021.

- Rosenlund, I.M.; Ingebrigtsen, T.; Johnsen, L.H.; Ringberg, U.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Isaksen, J. Are diagnoses of unruptured intracranial aneurysms associated with quality of life, psychological distress, health anxiety, or use of healthcare services in untreated individuals? A longitudinal, nested case-control study. Brain Spine 2024, 4, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Su, S.H.; Xu, W.; Hai, J.; Yu, F.; Wu, Y.F.; Liu, Y.G.; Zhang, L. Cognitive function, depression, anxiety and quality of life in Chinese patients with untreated unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 1734–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, M.; Román-Calderón, J.P.; Calle, G.; Gómez-Hoyos, J.F.; Jimenez, C.M. Personality and anxiety are related to health-related quality of life in unruptured intracranial aneurysm patients selected for non-intervention: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229795. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32163437/ (accessed on 31 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Buijs, J.E.; Greebe, P.; Rinkel, G.J. Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in patients with an unruptured intracranial aneurysm with or without aneurysm occlusion. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Schaaf, I.; Brilstra, E.H.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; van Gijn, J. Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients With an Untreated Intracranial Aneurysm or Arteriovenous Malformation. Stroke 2002, 33, 440–443. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11823649 (accessed on 31 October 2024). [CrossRef]

| Study | Design | No. Patients | Follow-Up (Years) | Age * | Female, % | Smoker, % | Alcohol Drinker, % | HTN, % | Aneurysmal Size, % # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li Y 2017 [1] | Retrospective comparative study | P: 80 C: 118 | NA | P: 55.8 C1: 58.7 C2: 56.2 | P: 70 C1: 79.5 C2: 64.9 | P: 28.8 C1: 11.4 C2: 20.3 | P: 30 C1: 18.2 C2: 16.2 | P: 38.8 C1: 52.3 C2: 48.6 | P: [1]-75, [2]-6.3, [3]-18.7 C1: [1]-68.2, [2]-18.2, [3]-13.6 C2: [1]-51.3, [2]-23.0, [3]-25.7 |

| Rosenlund IM 2024 [31] | Retrospective comparative study | P: 96 C: 192 | 5 | P: 65.2 C1: 65.2 C2: 65.2 | P: 59 C1: 59 C2: 59 | P: 19.2 C1: 13.1 C2: 15.3 | P: 11.6 C1: 8.4 C2: 4.8 | P: 39.1 C1: 31.4 C2: 29.4 | P: 3.1 C: 3.6 |

| Su SH 2014 [32] | Retrospective comparative study | P: 31 C: 25 | 5 | P: 48.1 ± 5.7 C: 49.5 ± 6.6 | P: 61 C: 64 | P: 39 C: 60 | P: 35 C: 44 | P: 42 C: 64 | P: [1]-83, [2]-11, [3]-6 C: NA |

| Kim YG 2024 [3] | Retrospective comparative study | P: 85,438 C: 331,123 | 10 | P: 56.41 C: 56.69 | P: 49.25 C: 50.56 | P: 16.5 C: 15.3 | P: 24.9 C: 23.3 | P: 47.1 C: 47 | NA |

| Towgood K 2005 [4] | Prospective comparative study | P: 23 C: 26 | NA | P: 50.22 C: 48.73 | P: 70 C: 58 | P: 36 C: 62 | P: 41 C: 23 | P: 55 C: 35 | P: [4]-52, [5]-17, [6]-9, [7]-22 C: [4]-42, [5]-31, [6]-19, [7]-8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Penchev, P.; Ivanov, K.; Milanova-Ilieva, D.; Gaydarski, L.; Kostov, K.; Boyadzhiev, N.; Petrov, P.-P.; Mehandzhiev, P.; Hyusein, R.; Velchev, V.; et al. Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 417,152 Patients with Trial Sequential Analysis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070764

Penchev P, Ivanov K, Milanova-Ilieva D, Gaydarski L, Kostov K, Boyadzhiev N, Petrov P-P, Mehandzhiev P, Hyusein R, Velchev V, et al. Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 417,152 Patients with Trial Sequential Analysis. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(7):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070764

Chicago/Turabian StylePenchev, Plamen, Kiril Ivanov, Daniela Milanova-Ilieva, Lyubomir Gaydarski, Kiril Kostov, Nikola Boyadzhiev, Petar-Preslav Petrov, Patrice Mehandzhiev, Remzi Hyusein, Vladislav Velchev, and et al. 2025. "Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 417,152 Patients with Trial Sequential Analysis" Brain Sciences 15, no. 7: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070764

APA StylePenchev, P., Ivanov, K., Milanova-Ilieva, D., Gaydarski, L., Kostov, K., Boyadzhiev, N., Petrov, P.-P., Mehandzhiev, P., Hyusein, R., Velchev, V., Ilyov, I., Kuzmanov, V., Dzhikova, G., Dobreva, D., Toptchiyska, L., Dimitrova, V., Petrova, V., Yorov, S., Stanchev, P., ... Ramadanov, N. (2025). Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Untreated Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 417,152 Patients with Trial Sequential Analysis. Brain Sciences, 15(7), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070764