Stress, Burnout and Study-Related Behavior in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Analysis Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Procedure and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D-R15)

2.2.2. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)

2.2.3. Maslach Burnout Inventory—Student Survey German Version (MBI-SS)

2.2.4. Modified Version of the Assessment of Work-Related Behavior and Experience Patterns (AVEM) Adapted for Students

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

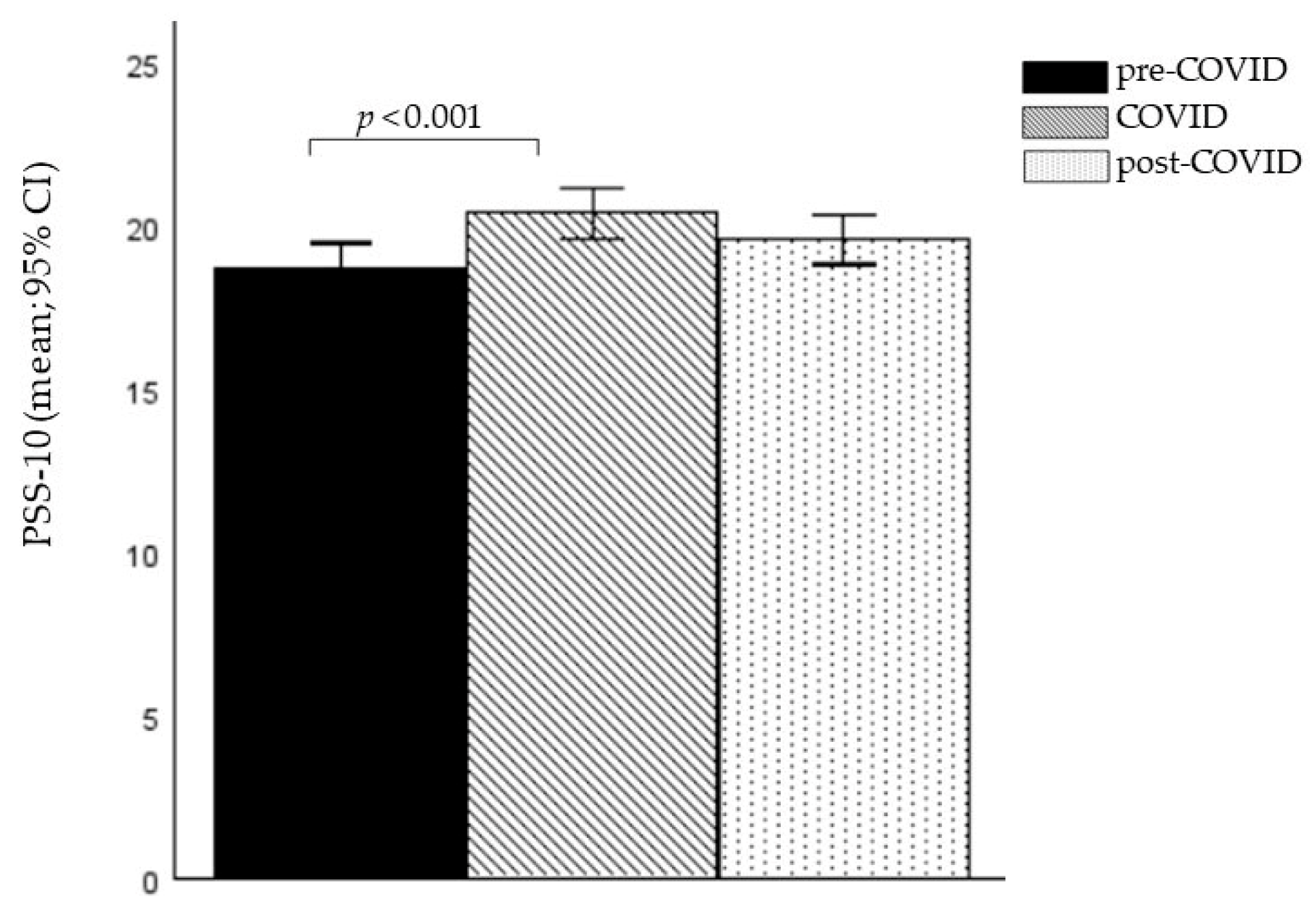

3.2. Stress and Depression

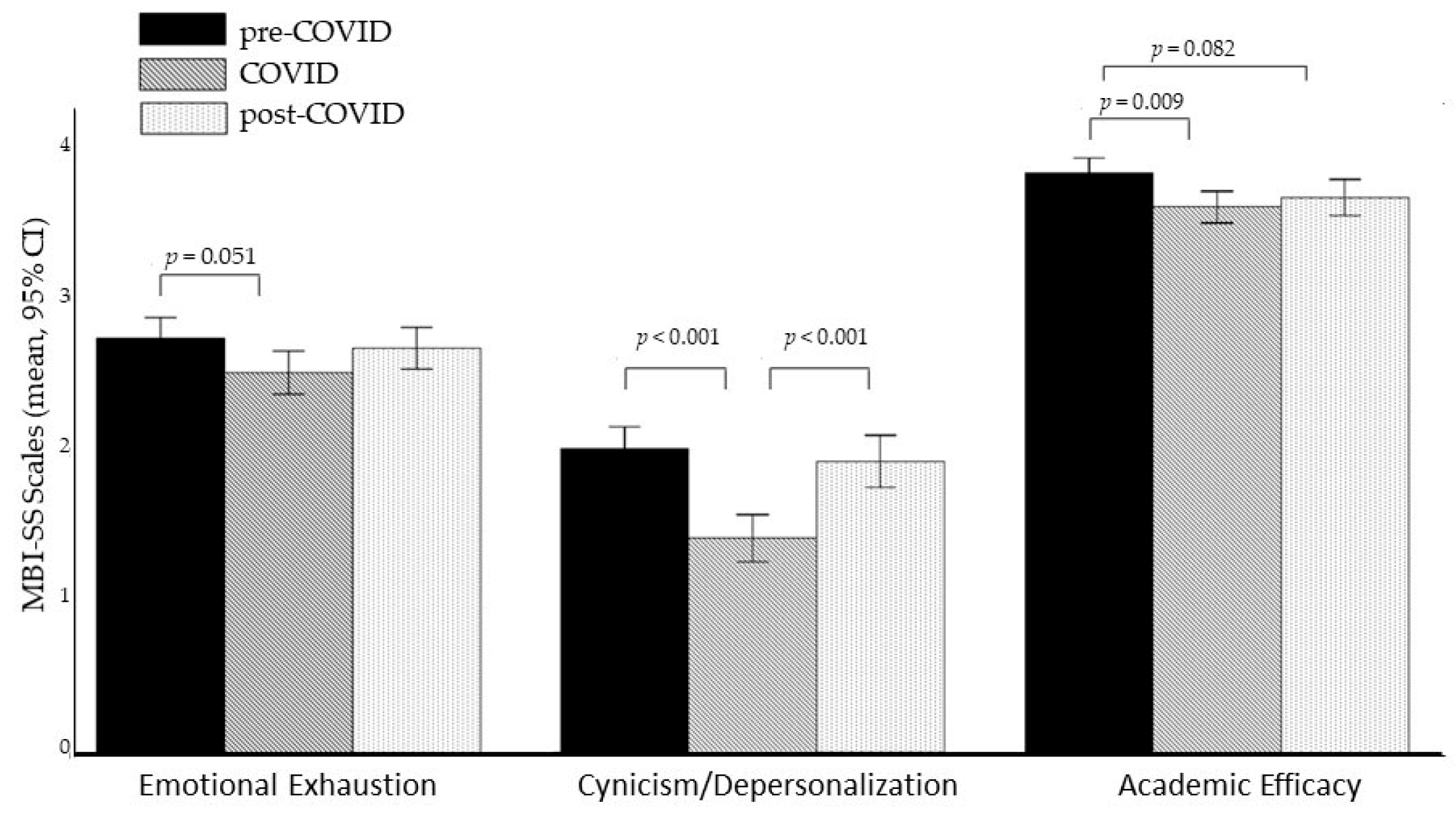

3.3. Burn-Out Symptoms

3.4. Assessment of Study Behavior and Experience Patterns

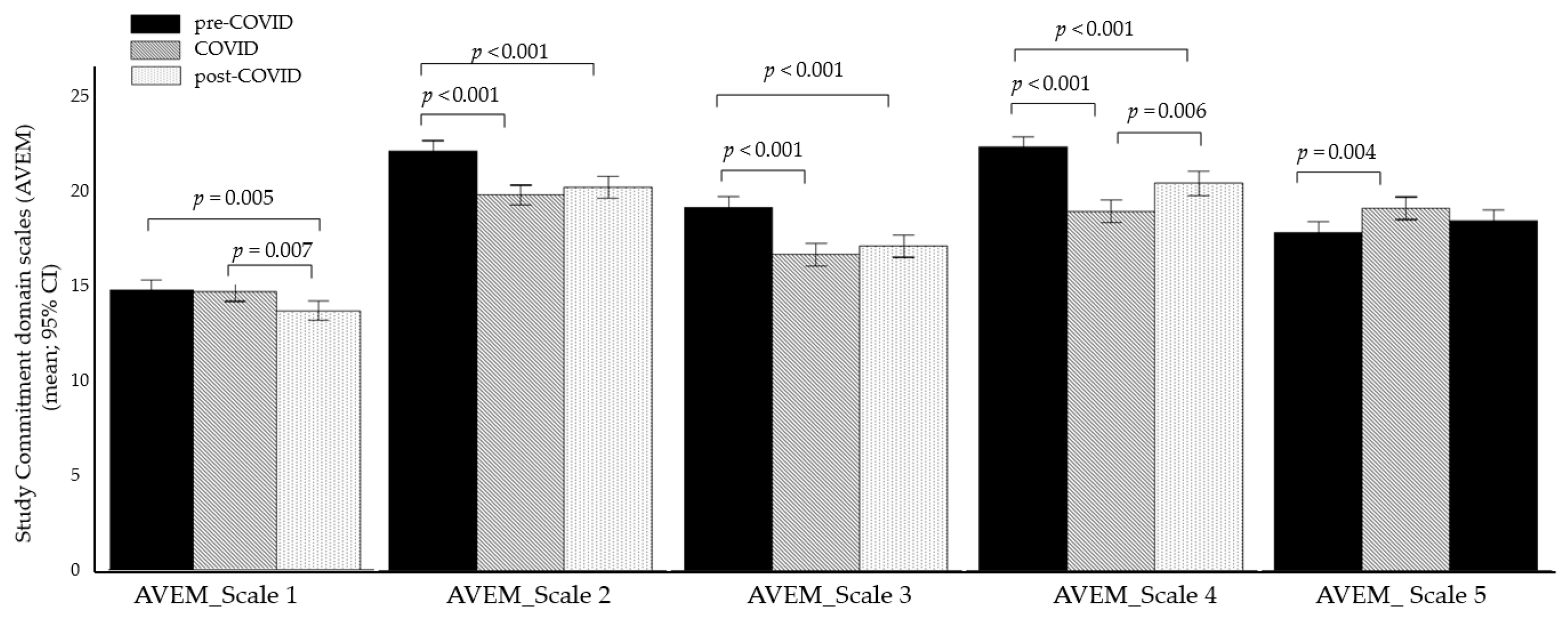

3.4.1. Study Commitment Domain (AVEM)

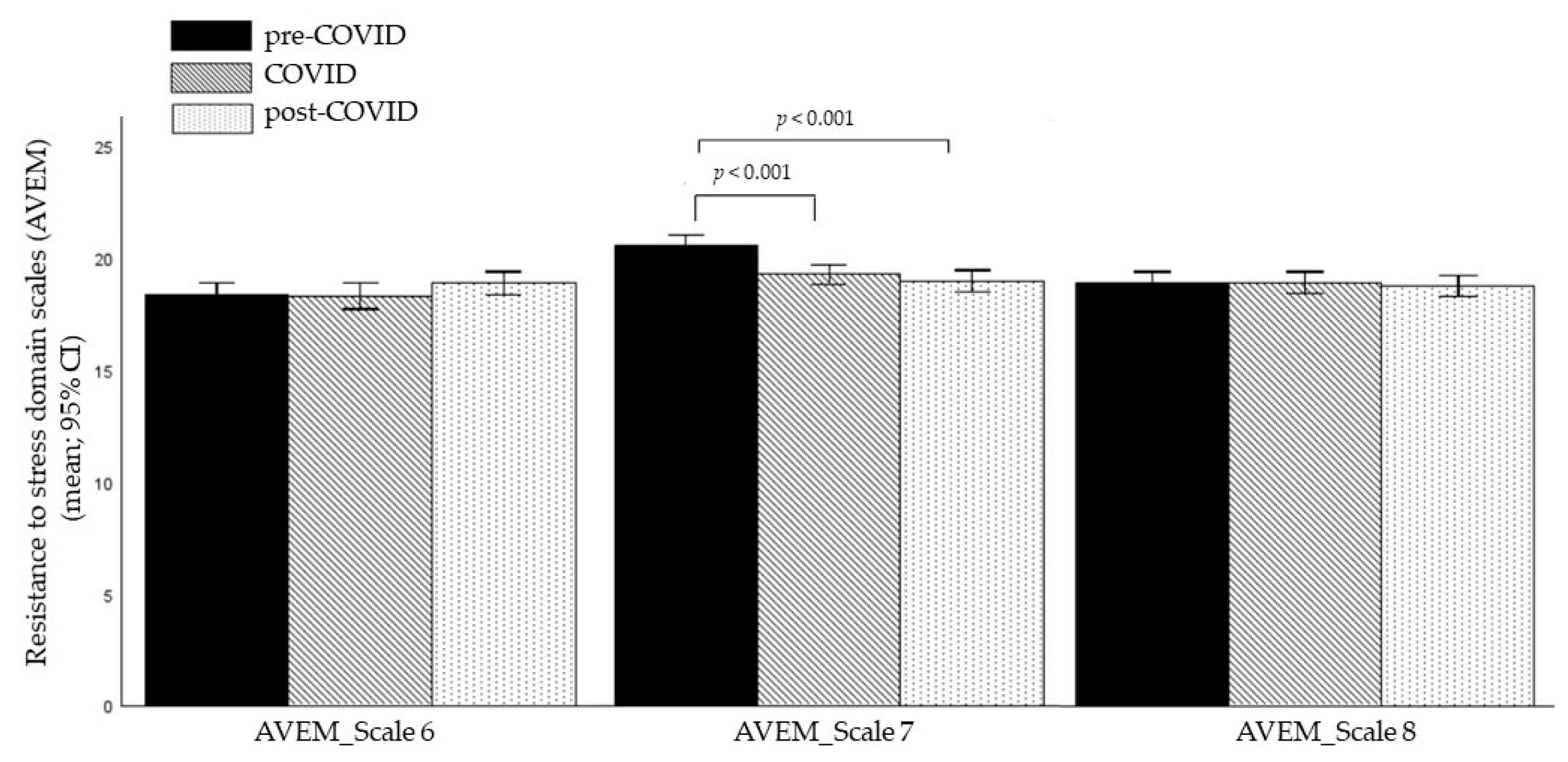

3.4.2. ‘Resistance to Stress’ Domain (AVEM)

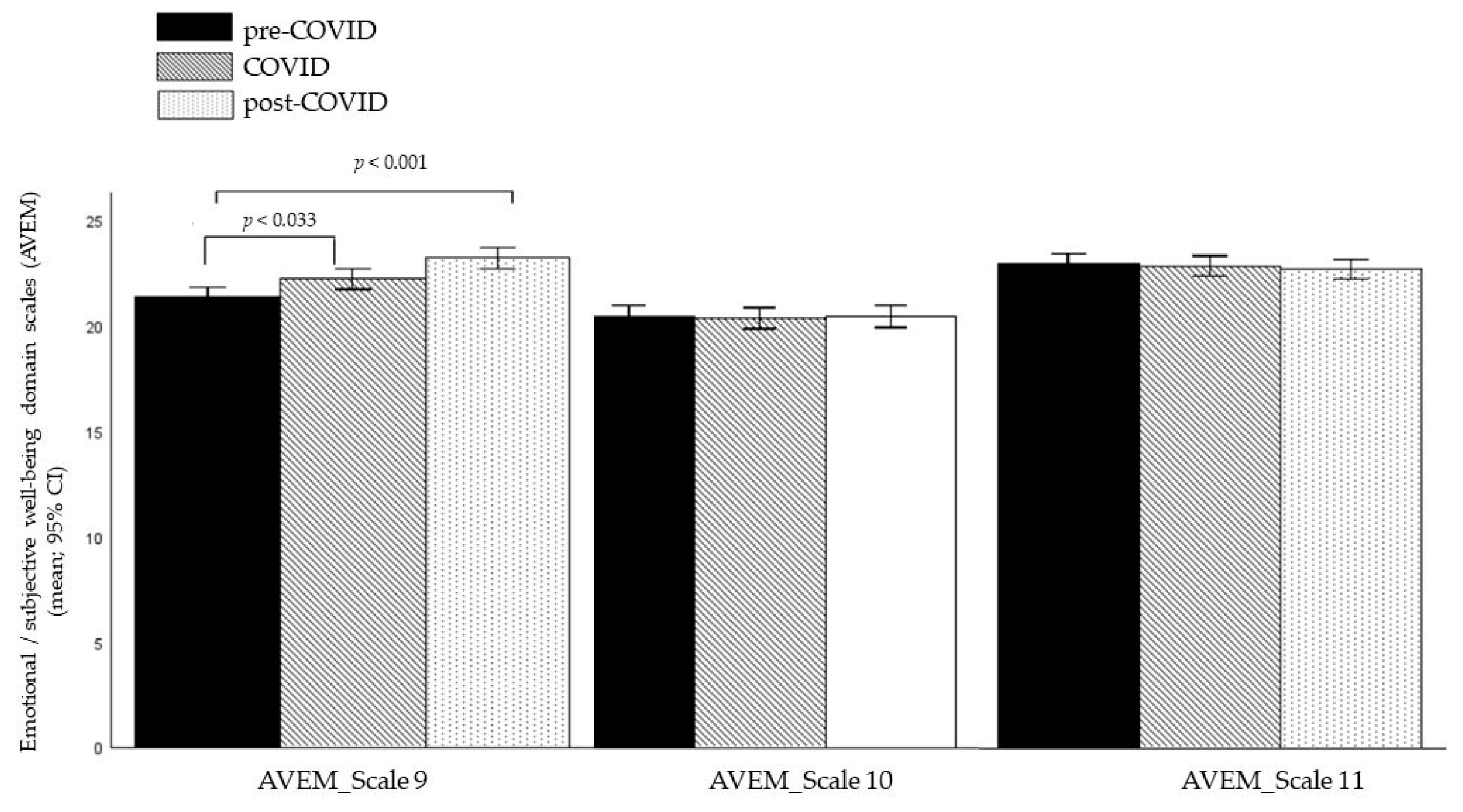

3.4.3. ‘Emotional or Subjective Well-Being’ Domain (AVEM)

4. Discussion

4.1. Symptoms of Stress and Depression

4.2. Burnout Symptoms

4.3. Study-Related Behavior and Experience

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVEM | Assessment of Work Behavior and Experience Patterns |

| CES-D-R15 | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale |

| MBI-SS | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Student Survey |

| MBI_EE | Emotional Exhaustion Subscale of the MBI-SS |

| MBI_Cyn/Dep | Cynicism/Depersonalization Subscale of the MBI-SS |

| MBI_Effic | Academic Efficacy of the MBI-SS |

| PSS-10 | Perceived Stress Scale |

References

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotham, D.; Julian, C. Stress and the higher education student: A critical review of the literature. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E.; Hunt, J. Mental health and academic success in college. BEJEAP 2009, 9, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Reinecke, L.; Müller, K.W.; Schmutzer, G.; Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale–psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochnik, D.; Rogowska, A.M.; Kuśnierz, C.; Jakubiak, M.; Schütz, A.; Held, M.J.; Arzenšek, A.; Benatov, J.; Berger, R.; Korchagina, E.V. Mental health prevalence and predictors among university students in nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, H. High prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among remote learning students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; et al. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.M.; Kaufmann, L.; Ninaus, M.; Canazei, M. Belastungen durch Fernlehre und psychische Gesundheit von Studierenden während der COVID-19-Pandemie. Lern. Lernstörungen 2022, 11, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, 11th ed.; ICD-11; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019/2021; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Ricardo, Y.; Rizzo-Chunga, F.; Mocha-Bonilla, J.; Ferreira, J.P. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in university students: A systematic review. Salud Ment. 2021, 44, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanto, T.; Chen, W.S.; Too, Y.Y. Academic burnout and eating disorder among students in Monash University Malaysia. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt, U.; Fischer, A.W. Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster AVEM, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye, L.; Shanafelt, T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frajerman, A.; Morvan, Y.; Krebs, M.-O.; Gorwood, P.; Chaumette, B. Burnout in medical students before residency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatr. 2019, 55, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Chaabna, K.; Sheikh, J.I.; Mamtani, R.; Jithesh, A.; Khawaja, S.; Cheema, S. Burnout increased among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Cañadas, G.R.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Pradas-Hernández, L.; Martos Cabrera, B.; Velando-Soriano, A.; de la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Levels of Burnout and Engagement after COVID-19 among Psychology and Nursing Students in Spain: A Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, R.; Fernandes, D.A.; Vásquez, A.; Trigueros, A.; Pemberton, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.N.; Torales, J.; Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. Prevalence of burnout in medical students in Guatemala: Before and during COVID-19 pandemic comparison. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Read, S. Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burn. Res. 2017, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriek, J.; Carstensen, B.; Soellner, R.; Klusmann, U. Pandemic rollercoaster: University students’ trajectories of emotional exhaustion, satisfaction, enthusiasm, and dropout intentions pre-, during, and post-COVID-19. Teach. Educ. 2024, 148, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolatov, A.K.; Seisembekov, T.Z.; Askarova, A.Z.; Baikanova, R.K.; Smailova, D.S.; Fabbro, E. Online learning due to COVID-19 improved mental health among medical students. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žuljević, M.F.; Jeličić, K.; Viđak, M.; Đogaš, V.; Buljan, I. Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on study satisfaction and burnout in medical students in Split, Croatia: A cross-sectional presurvey and postsurvey. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e049590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zis, P.; Artemiadis, A.; Bargiotas, P.; Nteveros, A.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Medical studies during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of digital learning on medical students’ burnout and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, X.; Xie, S.; Zhou, J. Prevalence of burnout and mental health problems among medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e061945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Upadyaya, K.; Ronkainen, I.; Hietajärvi, L. Study Burnout and Engagement During COVID-19 Among University Students: The Role of Demands, Resources, and Psychological Needs. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts: A review of empirical research. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, E.; Köslich-Strumann, S.; Walther, A.; Kasem, M.; Obst, K.; Kötter, T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, mental health, and coping behavior in German university students - A longitudinal study before and after the onset of the pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautzinger, M.; Bailer, M.; Hofmeister, D.; Keller, F. Allgemeine Depressionsskala; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gumz, A.; Erices, R.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M. Faktorstruktur und Gütekriterien der deutschen Übersetzung des Maslach-Burnout-Inventars für Studierende von Schaufeli et al. (MBI-SS). PPmP 2013, 63, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, V.; Glumann, N.V.; Kiesewetter, J. Auswirkungen der Corona-Pandemie auf die psycho-soziale Situation von Studienanfänger*innen und Studierenden im DACH-Raum. Ein systematischer Literaturreview. In Die Psycho-Soziale Situation Von Studierenden In Der (Post-)Pandemischen Zeit. Stand Der Forschung Und Impulse Aus Der Praxis; Hofmann, Y.E., Ed.; UVW Universitäts Verlag Webler: Bielefeld, Germany, 2024; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, S.; Licinio, J. Qualitative literature review of the prevalence of depression in medical students compared to students in non-medical degrees. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, M.; Brown, N.; Brady, J.; McLaughlin, J.; McHugh, R.; Ward, C.; McBride, L.; Bjourson, A.J.; O’Neill, S.M.; Walsh, C.P.; et al. Variations in psychological disorders, suicidality, and help-seeking behaviour among college students from different academic disciplines. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T.; James, C.; Pérez-Rojas, A.E. College students’ awareness of mental disorders and resources: Comparison across academic disciplines. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2022, 36, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Wagner, B.; Beck, K.; Eisenberg, D. Major differences: Variations in undergraduate and graduate student mental health and treatment utilization across academic disciplines. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2016, 30, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Abramson, L.Y. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangasser, D.A.; Eck, S.R.; Ordoñes Sanchez, E. Sex differences in stress reactivity in arousal and attention systems. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaab, D.F.; Bao, A.M. Sex differences in stress-related disorders: Major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2020, 175, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Bao, G.; Huang, Y.; Ji, B.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, G. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 244, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.J.; Niu, G.F.; You, Z.Q.; Zhou, Z.K.; Tang, Y. Gender, negative life events, and coping on different stages of depression severity: A cross-sectional study among Chinese university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 209, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.J.; Lo, K.H.K.; Ho, R.C.M.; Tam, W.S.W. Prevalence of depression among nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 63, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaisy, L.M. The relation of depression and anxiety in academic achievement among a group of university students. Int. J. Psychol. Couns. 2011, 3, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P.A.; Baker, E.H.; Milner, A.N. The role of sex, gender, and education on depressive symptoms among young adults in the United States. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.G.; Cheung, E.P.; Chan, K.K.; Ma, K.K.; Tang, S.W. Web-based survey of depression, anxiety, and stress in first-year tertiary education students in Hong Kong. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, K.; Marsh, P.; Syniar, G.; Williams, M.; Addlesperger, E.; Kinzler, M.H.; Cowman, S. Gender differences in rates of depression among undergraduates: Measurement matters. J. Adolesc. 2002, 25, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and the gender mental health gap. Health Serv. Res. 2025, 60, e14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, T.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, K.; Bonardi, O.; Krishnan, A.; Boruff, J.T.; et al. Systematic review of mental health symptom changes by sex or gender in early-COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-COVID n = 364 | COVID n = 350 | Post-COVID n = 302 | Total n = 1016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years]: mean (SD) | 23.17 (3.23) | 23.53 (3.81) | 24.95 (4.09) | 23.82 (3.77) |

| Gender (n,%) | ||||

| female | 249 (68.4%) | 266 (76.0%) | 218 (72.2%) | 733 (72.2%) |

| Male | 115 (31.6%) | 84 (24.0%) | 81 (26.8%) | 280 (27.6%) |

| Diverse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/divorced | 157 (43.1%) | 167(47.7%) | 137 (45.4%) | 461(45.4%) |

| Married/with a life partner | 207 (56.9%) | 183 (52.3%) | 165 (54.6%) | 555 (54.6%) |

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 6 (1.7%) | 8 (2.3%) | 9 (3%) | 23 (2.3%) |

| No | 358 (98.3%) | 342 (97.7%) | 293 97%) | 993 (97.7%) |

| Additional Job | ||||

| Yes | 181 (49.7%) | 145 (41.4%) | 198 (65.6%) | 524 (51.6%) |

| No | 183 (50.3%) | 205 (58.6%) | 104 (34.4%) | 492 (48.4) |

| Level of education (n,%) | ||||

| Bachelor | 247 (79.2%) | 270 (77.1%) | 175 (67.6%) | 692 (71.8%) |

| Master | 65 (20.8%) | 71 (20.3%) | 123 (27.6%) | 259 (26.9%) |

| PhD | 0 (0%) | 9 (2.6%) | 4 (1.8%) | 13 (1.3%) |

| University courses (n,%) | ||||

| Psychology | 85 (23.4%) | 173 (49.4%) | 161 (53.3%) | 419 (41.3%) |

| Medicine | 50 (13.7%) | 26 (7.4%) | 5 (1.7%) | 81 (8.0%) |

| Law | 40 (11.0%) | 16 (4.6%) | 5 (1.7%) | 61 (6.0%) |

| Natural Science | 37 (10.2%) | 29 (8.3%) | 8 (2.7%) | 74 (7.3%) |

| Social Sciences and Humanities | 110 (30.2%) | 89 (25.4%) | 105 (34.8%) | 304 (29.9%) |

| Engineering and Technology | 42 (11.5%) | 17 (4.9%) | 18 (6.0%) | 77 (7.6%) |

| Pre-COVID Mean (SD) | COVID Mean (SD) | Post-COVID Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D-R15 | 28.88 (9.37) | 29.97(9.85) | 29.36 (8.82) |

| PSS-10 | 18.7 (7.59) | 20.38 (7.57) | 19.57 (6.61) |

| MBI-SS | |||

| MBI_EE | 2.73 (1.31) | 2.50 (1.35) | 2.66 (1.21) |

| MBI_Cyn/Dep | 1.99 (1.42) | 1.41 (1.47) | 1.91 (1.52) |

| MBI_Effic | 3.81 (0.99) | 3.59 (1) | 3.66 (1.05) |

| AVEM | |||

| AVEM Study Commitment | |||

| Scale 1: Perceived Significance | 14.57 (4.85) | 14.45 (4.65) | 13.48 (4.42) |

| Scale 2: Academic Goals/Ambition | 21.37 (5.06) | 19.13 (4.77) | 19.52 (4.85) |

| Scale 3: Commitment | 18.5 (5.36) | 16.09 (5.45) | 16.52 (4.95) |

| Scale 4: Striving for Perfection | 21.57 (4.89) | 18.31 (5.44) | 19.72 (5.39) |

| Scale 5: Emotional Distancing | 17.21 (5.37) | 18.46 (5.51) | 17.82 (4.88) |

| AVEM Resistance to Stress | |||

| Scale 6: Tendency to Resignation | 18.34 (5) | 18.29 (5.5) | 18.86 (4.51) |

| Scale 7: Active Coping | 20.71 (4.43) | 19.4 (4.09) | 19.11 (4.23) |

| Scale 8: Balance and Emotional Stability | 19 (5.01) | 19.03 (4.62) | 18.89 (4.06) |

| AVEM Emotional or Subjective Well-Being | |||

| Scale 9: Satisfaction with Studies | 21.32 (4.68) | 22.19 (4.57) | 23.19 (4.48) |

| Scale 10: Life Satisfaction | 20.57 (5.09) | 20.49 (4.81) | 20.58 (4.56) |

| Scale 11: Perceived Social Support | 23.29 (4.67) | 23.19 (4.64) | 23.04 (4.16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dresen, V.; Staggl, S.; Fischer-Jbali, L.; Canazei, M.; Weiss, E. Stress, Burnout and Study-Related Behavior in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Analysis Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070718

Dresen V, Staggl S, Fischer-Jbali L, Canazei M, Weiss E. Stress, Burnout and Study-Related Behavior in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Analysis Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(7):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070718

Chicago/Turabian StyleDresen, Verena, Siegmund Staggl, Laura Fischer-Jbali, Markus Canazei, and Elisabeth Weiss. 2025. "Stress, Burnout and Study-Related Behavior in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Analysis Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic" Brain Sciences 15, no. 7: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070718

APA StyleDresen, V., Staggl, S., Fischer-Jbali, L., Canazei, M., & Weiss, E. (2025). Stress, Burnout and Study-Related Behavior in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Analysis Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Sciences, 15(7), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15070718