Approach to Patients with Dysphagia: Clinical Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology of Dysphagia

3. Causes of Dysphagia

3.1. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

3.2. Esophageal Dysphagia

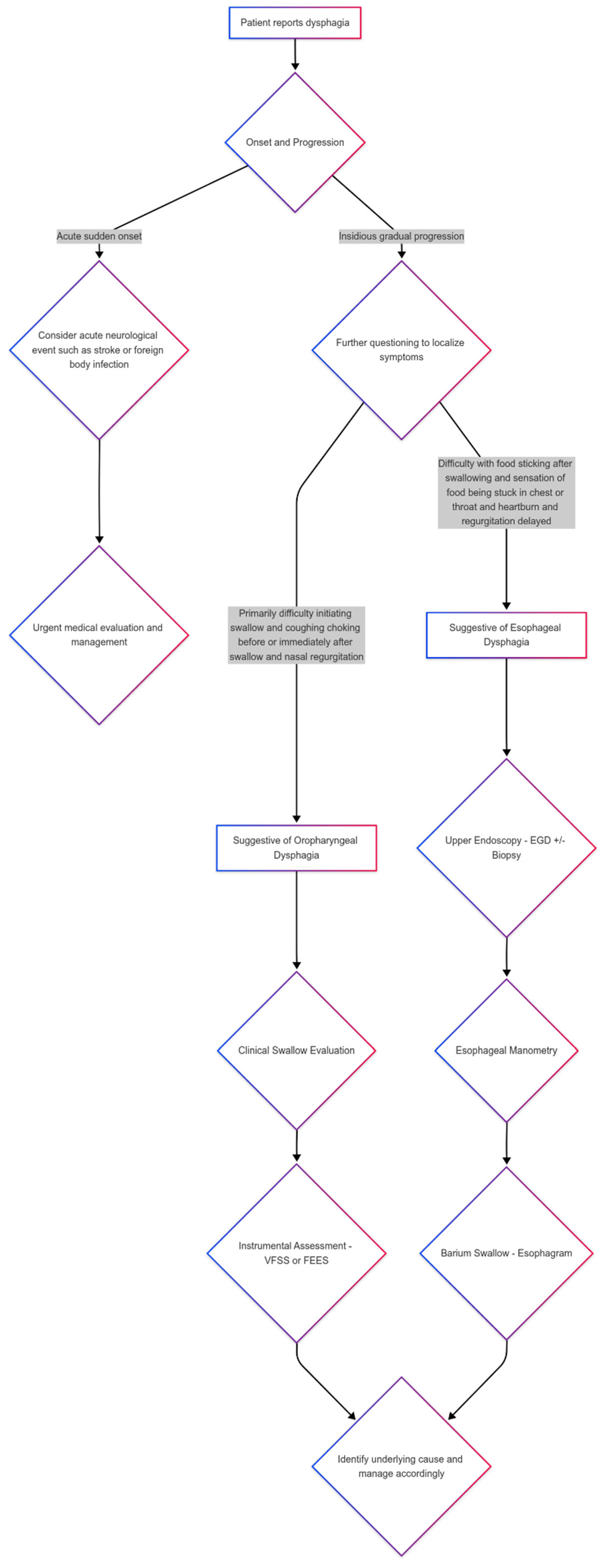

4. Differential Diagnosis Between Oropharyngeal and Esophageal Dysphagia

5. Dysphagia Examination

5.1. Video Fluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS)

5.2. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES)

5.3. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rofes, L.; Muriana, D.; Palomeras, E.; Vilardell, N.; Palomera, E.; Alvarez-Berdugo, D.; Casado, V.; Clavé, P. Prevalence, risk factors and complications of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients: A cohort study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Choung, R.S.; Saito, Y.A.; Schleck, C.D.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Locke, G.R., 3rd; Talley, N.J. Prevalence and risk factors for dysphagia: A USA community study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 27, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuercher, P.; Moret, C.S.; Dziewas, R.; Schefold, J.C. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.W.C.; Andrews, C.N.; Armstrong, D.; Diamant, N.; Jaffer, N.; Lazarescu, A.; Li, M.; Martino, R.; Paterson, W.; Leontiadis, G.I.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Assessment of Uninvestigated Esophageal Dysphagia. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2018, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagalingam, S.; Kulinski, A.E.; Thorsteinsdottir, B.; Shindelar, K.L.; Takahashi, P.Y. Dysphagia in Older Adults. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, N.; Hamdy, S. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: Manifestations and diagnosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhnevich, A.; Perrin, A.; Talukder, D.; Liu, Y.; Izard, S.; Chiuzan, C.; D’Angelo, S.; Affoo, R.; Rogus-Pulia, N.; Sinvani, L. Thick Liquids and Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias and Dysphagia. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.G.; Isaac, M.J.; Gillespie, M.B.; O’Rourke, A.K. The Incidence and Characterization of Globus Sensation, Dysphagia, and Odynophagia Following Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, F.; Rommel, N.; Pandolfino, J.; Gyawali, C.P. ESNM/ANMS Review. Diagnosis and management of globus sensation: A clinical challenge. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomze, L.; Dehom, S.; Lao, W.P.; Thompson, J.; Lee, N.; Cragoe, A.; Luceno, C.; Crawley, B. Comorbid Dysphagia and Malnutrition in Elderly Hospitalized Patients. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 2441–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pede, C.; Mantovani, M.E.; Del Felice, A.; Masiero, S. Dysphagia in the elderly: Focus on rehabilitation strategies. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, S.; Menclova, A.; Huckabee, M.L. Estimating the Incidence and Prevalence of Dysphagia in New Zealand. Dysphagia 2024, 39, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Ma, Y.N.; Karako, K.; Tang, W.; Song, P.; Xia, Y. Comprehensive assessment and treatment strategies for dysphagia in the elderly population: Current status and prospects. Biosci. Trends 2024, 18, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, C.J.; Tulunay-Ugur, O.E. Dysphagia in the Aging Population. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 57, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, C.; O’Loughlin, G. Dysphagia among nursing home residents: An assessment and management protocol. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2000, 26, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talley, N.J.; Weaver, A.L.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 136, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Han, X.; Yang, Q.; Lin, T.; Zhou, H.; Tang, M.; Zhou, J.; Shi, H.; et al. Prevalence of Dysphagia in China: An Epidemiological Survey of 5943 Participants. Dysphagia 2021, 36, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Sapia, M.; Walker, C.; Pittaoulis, M. Dysphagia Prevalence in Brazil, UK, China, and Indonesia and Dysphagic Patient Preferences. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Cha, S.; Kim, J.; Han, K.; Paik, N.J.; Kim, W.S. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of dysphagia requiring medical attention among adults in South Korea, 2006-2016: A nationwide population study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, W.V.; Arreola, V.; Sanz, P.; Necati, E.; Bolivar-Prados, M.; Michou, E.; Ortega, O.; Clavé, P. Pathophysiology of Swallowing Dysfunction in Parkinson Disease and Lack of Dopaminergic Impact on the Swallow Function and on the Effect of Thickening Agents. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.-W.; Lee, C.-S.; Lim, D.-W.; Noh, S.-H.; Moon, H.-K.; Park, C.; Kim, M.-S. The Development of an Artificial Intelligence Video Analysis-Based Web Application to Diagnose Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roden, D.F.; Altman, K.W. Causes of dysphagia among different age groups: A systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 46, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, R.; Dziewas, R.; Beck, A.M.; Clavé, P.; Hamdy, S.; Heppner, H.J.; Langmore, S.; Leischker, A.H.; Martino, R.; Pluschinski, P.; et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons—From pathophysiology to adequate intervention: A review and summary of an international expert meeting. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labeit, B.; Michou, E.; Hamdy, S.; Trapl-Grundschober, M.; Suntrup-Krueger, S.; Muhle, P.; Bath, P.M.; Dziewas, R. The assessment of dysphagia after stroke: State of the art and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeit, B.; Michou, E.; Trapl-Grundschober, M.; Suntrup-Krueger, S.; Muhle, P.; Bath, P.M.; Dziewas, R. Dysphagia after stroke: Research advances in treatment interventions. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewas, R.; Michou, E.; Trapl-Grundschober, M.; Lal, A.; Arsava, E.M.; Bath, P.M.; Clavé, P.; Glahn, J.; Hamdy, S.; Pownall, S.; et al. European Stroke Organisation and European Society for Swallowing Disorders guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of post-stroke dysphagia. Eur. Stroke J. 2021, 6, Lxxxix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, C.H.; Chiang, H.C.; Huang, L.C.; Yang, Y.H.; Hung, C.H. The Mortality and the Risk of Aspiration Pneumonia Related with Dysphagia in Stroke Patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, K.J.; Chu, H.; Kang, X.L.; Liu, D.; Pien, L.C.; Jen, H.J.; Hsiao, S.S.; Chou, K.R. Prevalence of dysphagia and risk of pneumonia and mortality in acute stroke patients: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, G.; Todisco, M.; Giudice, C.; Tassorelli, C.; Alfonsi, E. Assessment and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia in stroke and Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2022, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.; Sasegbon, A.; Hamdy, S. Dysphagia treatments in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 35, e14517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.H.N.; Low, E.E.; Yadlapati, R. Evaluation of Esophageal Dysphagia in Elderly Patients. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2023, 25, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidambi, T.; Toto, E.; Ho, N.; Taft, T.; Hirano, I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999–2009. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 4335–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Jin, G.F.; Shen, H.B. Epidemiologic differences in esophageal cancer between Asian and Western populations. Chin. J. Cancer 2012, 31, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronkainen, J.; Agréus, L. Epidemiology of reflux symptoms and GORD. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.K. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: A systematic review. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 17, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.W.; Lim, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.L.; Lee, O.Y.; Park, J.M.; Choi, M.G.; Rhee, P.L. Prevalence of Extraesophageal Symptoms in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Multicenter Questionnaire-based Study in Korea. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 20, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, J.; Rofes, L.; Serra-Prat, M.; Icart, R.; Palomera, E.; Arreola, V.; Clavé, P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a risk factor for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, R.; Foley, N.; Bhogal, S.; Diamant, N.; Speechley, M.; Teasell, R. Dysphagia after stroke: Incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke 2005, 36, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomik, J.; Sowula, K.; Dworak, M.; Stolcman, K.; Maraj, M.; Ceranowicz, P. Esophageal Peristalsis Disorders in ALS Patients with Dysphagia. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaden, E.; Burnell, J.; Hives, L.; Dey, P.; Clegg, A.; Lyons, M.W.; Lightbody, C.E.; Hurley, M.A.; Roddam, H.; McInnes, E.; et al. Screening for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, Cd012679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffer, N.M.; Ng, E.; Au, F.W.; Steele, C.M. Fluoroscopic evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia: Anatomic, technical, and common etiologic factors. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwald Pauletti, R.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Fornari, L.; de Moraes, J.I.; Fornari, F. Reduced masticatory function predicts gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophageal dysphagia in patients referred for upper endoscopy: A cross-sectional study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazinatto, D.B.; Brandão, M.A.B.; Costa, F.L.P.; Favaro, M.M.A.; Maunsell, R. Role of fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) in children with suspected dysphagia. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhm, K.E.; Yi, S.H.; Chang, H.J.; Cheon, H.J.; Kwon, J.Y. Videofluoroscopic swallowing study findings in full-term and preterm infants with Dysphagia. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 37, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehraban-Far, S.; Alrassi, J.; Patel, R.; Ahmad, V.; Browne, N.; Lam, W.; Jiang, Y.; Barber, N.; Mortensen, M. Dysphagia in the elderly population: A Videofluoroscopic study. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulheren, R.W.; González-Fernández, M. Swallow Screen Associated with Airway Protection and Dysphagia After Acute Stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.W. Usefulness of Early Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study in Acute Stroke Patients with Dysphagia. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 42, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, I.; Woo, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, T.L.; Lee, Y.; Chang, W.K.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, W.H.; Oh, B.M.; Han, T.R.; et al. Inter-rater and Intra-rater Reliability of the Videofluoroscopic Dysphagia Scale with the Standardized Protocol. Dysphagia 2024, 39, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Choi, K.H.; Kim, H.M.; Koo, J.H.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, T.W.; Ryu, J.S.; Im, S.; Choi, I.S.; Pyun, S.B.; et al. Inter-rater Reliability of Videofluoroscopic Dysphagia Scale. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 36, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilarajah, S.; Mentiplay, B.F.; Bower, K.J.; Tan, D.; Pua, Y.H.; Williams, G.; Koh, G.; Clark, R.A. Factors Associated with Post-Stroke Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 1876–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, A.P.G.; Rigobello, M.C.G.; Silveira, R.; Gimenes, F.R.E. Nasogastric/nasoenteric tube-related adverse events: An integrative review. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2021, 29, e3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leder, S.B.; Espinosa, J.F. Aspiration Risk After Acute Stroke: Comparison of Clinical Examination and Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing. Dysphagia 2002, 17, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsyaad, M.S.A.; Fayed, A.M.; Megahed, M.; Hamouda, N.H.; Elmenshawy, A.M. Early assessment of aspiration risk in acute stroke by fiberoptic endoscopy in critically ill patients. Acute Crit. Care 2022, 37, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checklin, M.; Dahl, T.; Tomolo, G. Feasibility and Safety of Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing in People with Disorder of Consciousness: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.R.; Borges, T.G.V.; Muniz, C.R.; Brendim, M.P.; Muxfeldt, E.S. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing in Resistant Hypertensive Patients with and Without Sleep Obstructive Apnea. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.H.; Park, H.; Park, S.J.; Song, C.M.; Chung, E.-J.; Kwon, T.-K.; Jin, Y.J. Standardization of FEES Evaluation for the Accurate Diagnosis of Dysphagia. J. Korean Dysphagia Soc. 2022, 12, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, M.G. An Evidence-Based Approach to the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Higuchi, K.; Sasaki, S.; Mori, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Hakoda, A.; Sugawara, N.; Iwatsubo, T.; Nishikawa, H. Frontiers in Endoscopic Treatment for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Digestion 2024, 105, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajulu, S.; Eloubeidi, M.A.; Patel, R.S.; Mulcahy, H.E.; Barkun, A.; Jowell, P.; Libby, E.; Schutz, S.; Nickl, N.J.; Cotton, P.B. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 61, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.S.; Rubesin, S.E. Diseases of the esophagus: Diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005, 237, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, Y.; Ihara, E.; Wada, M.; Tsuru, H.; Muta, K.; Minoda, Y.; Bai, X.; Esaki, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Chinen, T.; et al. Improved esophagography screening for esophageal motility disorders using wave appearance and supra-junctional ballooning. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, T.; Tomita, T.; Mori, S.; Takimoto, M.; Tamura, A.; Hara, K.; Kondo, T.; Kono, T.; Tozawa, K.; Ohda, Y.; et al. Esophagography in Patients with Esophageal Achalasia Diagnosed with High-resolution Esophageal Manometry. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oropharyngeal Dysphagia | Esophageal Dysphagia |

|---|---|

| Neurological | Neuromuscular diseases |

| Stroke | Achalasia |

| Parkinson’s disease | Scleroderma |

| Acquired brain injuries | Connective tissue disease |

| Neurodegenerative disorders | Mucosal diseases |

| Brain tumors | Peptic stricture |

| Neuromuscular | Esophageal rings and webs |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Esophageal tumors |

| Myasthenia gravis | Radiation therapy |

| Polymyositis | Infectious esophagitis |

| Myopathies | Eosinophilic esophagitis |

| Mechanical | Others |

| Cervical osteophytes | Foreign bodies |

| Goiter | Medication adverse effect |

| Oropharyngeal neoplasms | |

| Zenker diverticulum | |

| Others | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | |

| Medication adverse effect | |

| Radiation therapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.-S. Approach to Patients with Dysphagia: Clinical Insights. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050478

Kim M-S. Approach to Patients with Dysphagia: Clinical Insights. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(5):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050478

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Min-Su. 2025. "Approach to Patients with Dysphagia: Clinical Insights" Brain Sciences 15, no. 5: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050478

APA StyleKim, M.-S. (2025). Approach to Patients with Dysphagia: Clinical Insights. Brain Sciences, 15(5), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050478