Phonological Neighborhood Density and Type Modulate Visual Recognition of Mandarin Chinese: Evidence from Monosyllabic Words

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli and Design

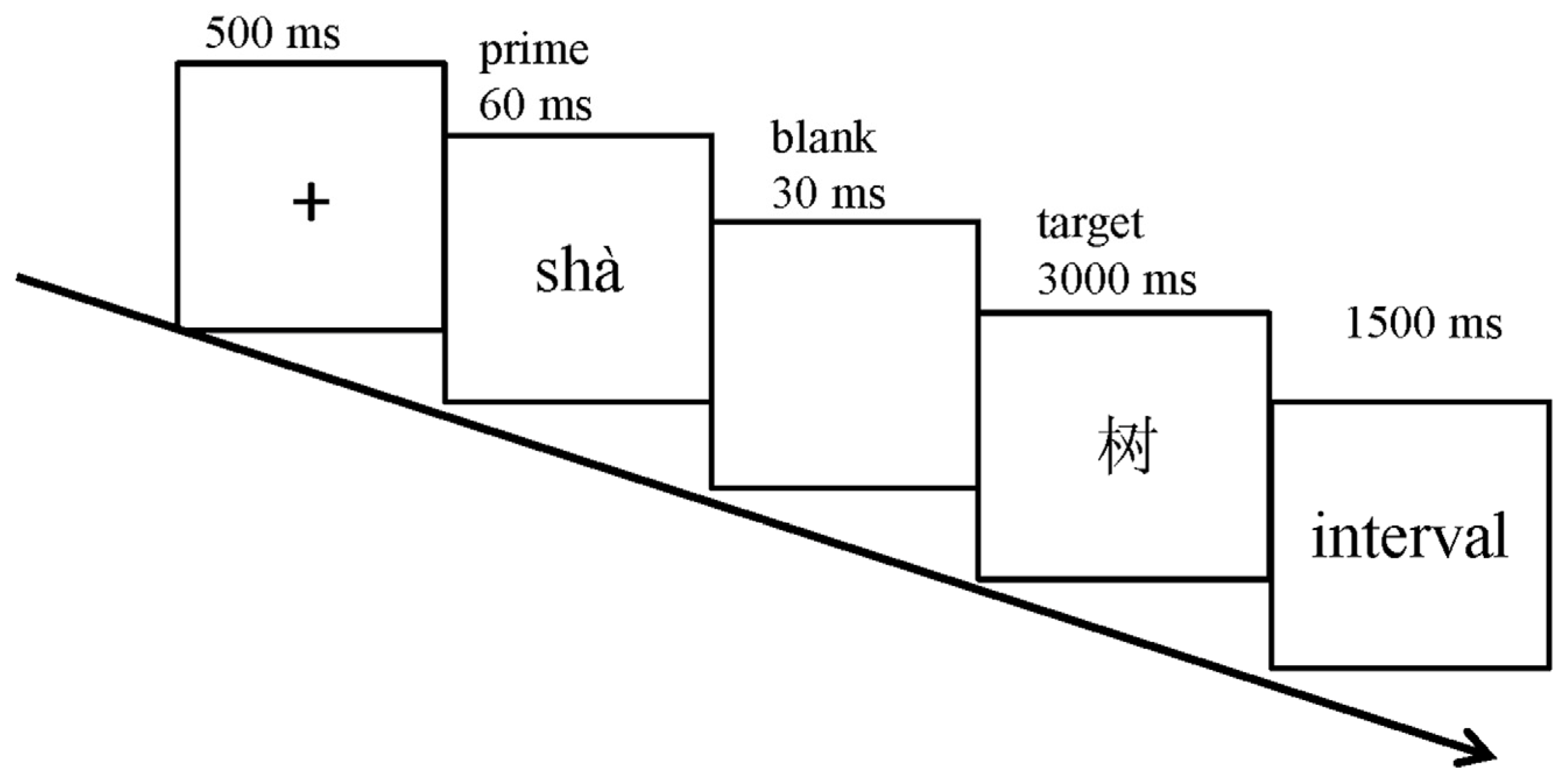

2.3. Apparatus and Procedure

2.4. EEG Recording and Preprocessing

3. Results

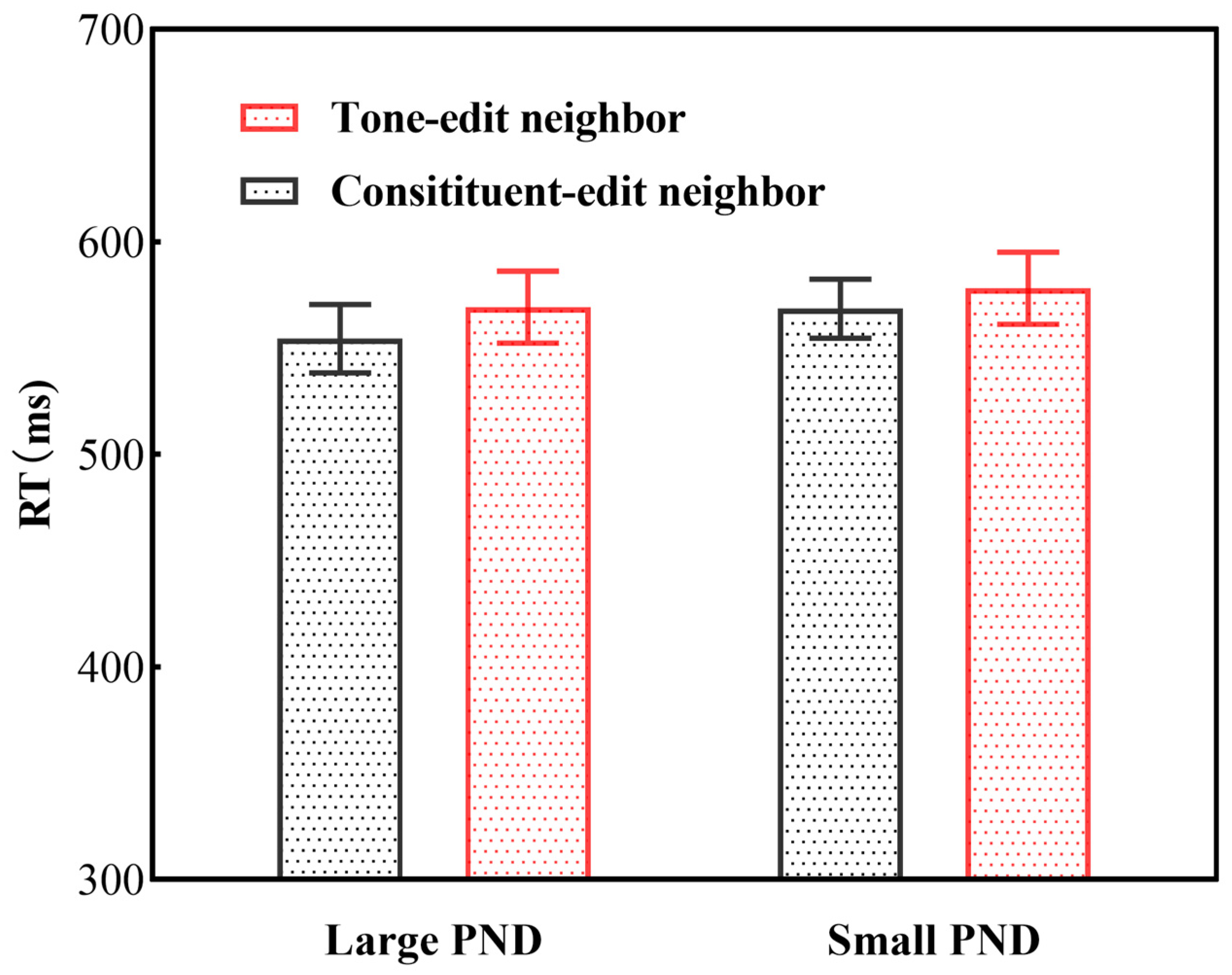

3.1. Behavioral Data

3.1.1. Non-Words

3.1.2. Real-Words

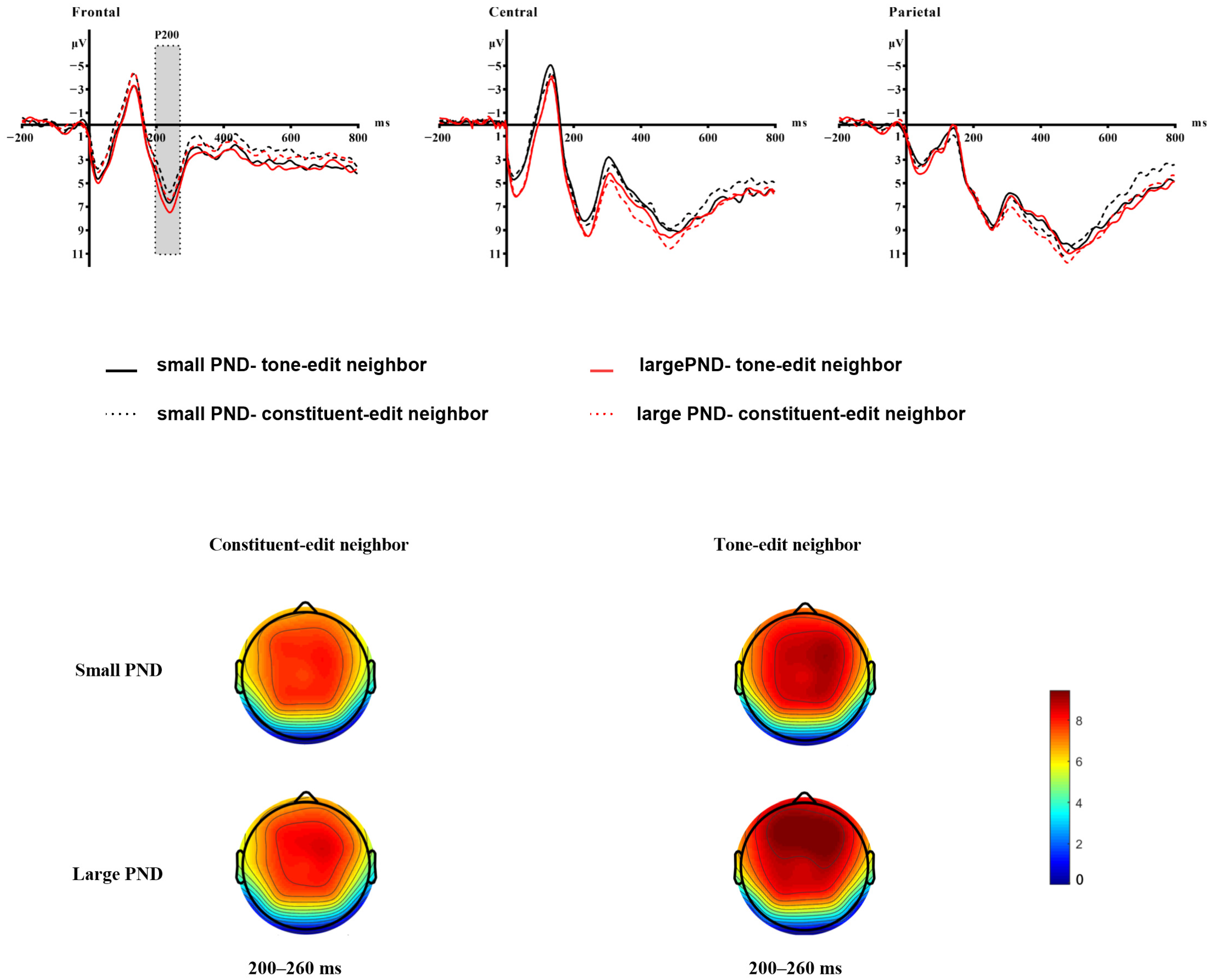

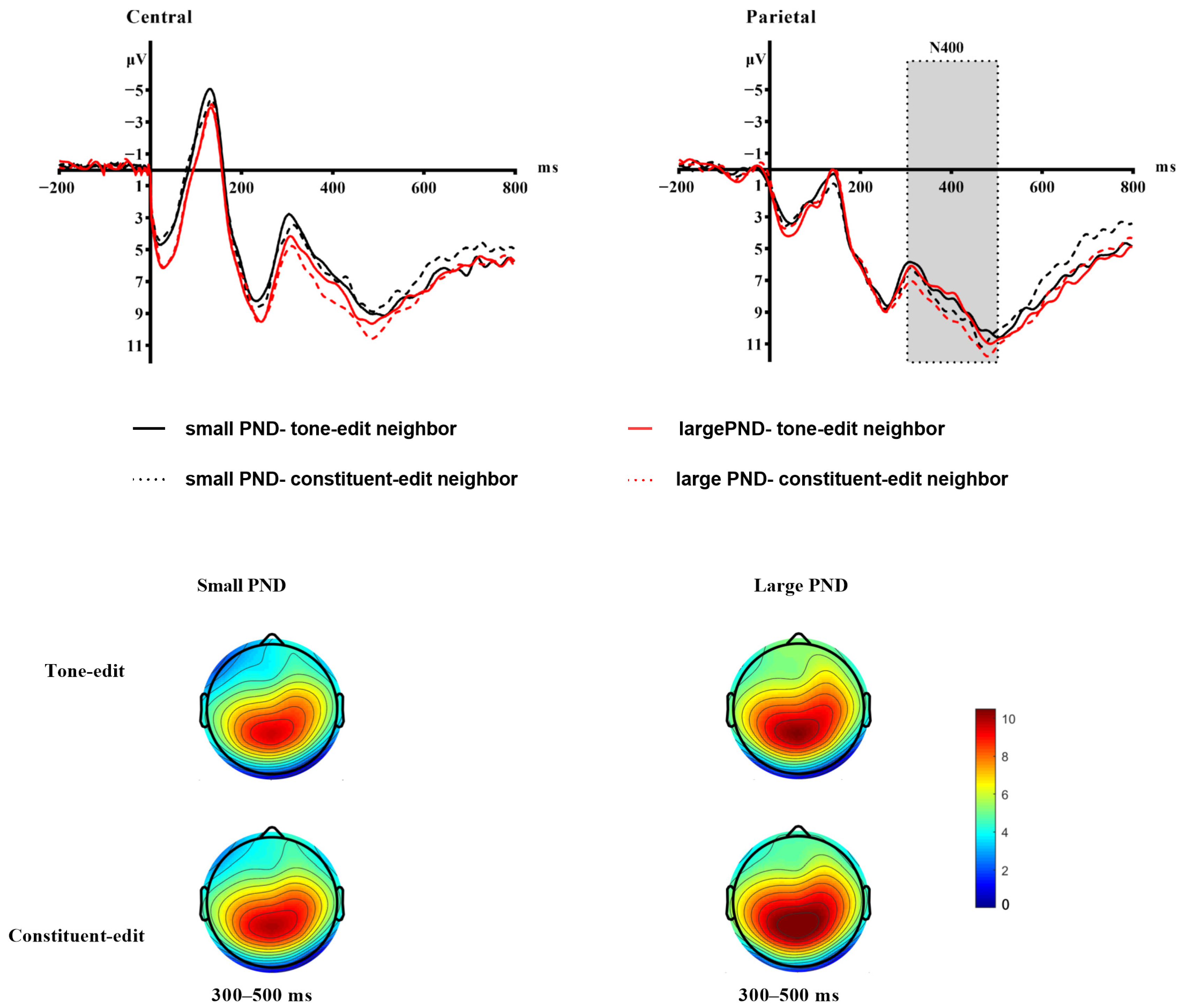

3.2. ERP Data

3.2.1. P200 (200–260 ms)

3.2.2. N400 (300–500 ms)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grainger, J.; Ferrand, L. Phonology and orthography in visual word recognition: Effects of masked homophone primes. J. Mem. Lang. 1994, 33, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, J.; Kiyonaga, K.; Holcomb, P.J. The time course of orthographic and phonological code activation. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastle, K.; Brysbaert, M. Masked phonological priming effects in English: Are they real? Do they matter? Cogn. Psychol. 2006, 53, 97–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, M.; Locker, L.; Simpson, G.B. The influence of phonological neighborhood on visual word perception. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2004, 11, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, M. Phonological neighbors speed visual word processing: Evidence from multiple tasks. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2005, 31, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Vaid, J.; Boas, D.A.; Bortfeld, H. Examining the phonological neighborhood density effect using near infrared spectroscopy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, T.K.; Streeter, L.A. Structural differences between common and rare words: Failure of equivalence assumptions for theories of word recognition. J. Verb. Learning Verb. Behav. 1973, 12, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, J.; Muneaux, M.; Farioli, F.; Ziegler, J.C. Effects of phonological and orthographic neighbourhood density interact in visual word recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. A 2005, 58, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitevitch, M.S.; Rodríguez, E. Neighborhood density effects in spoken word recognition in Spanish. J. Multiling. Commun. Disord. 2004, 3, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutiunian, V.; Lopukhina, A. The effects of phonological neighborhood density in childhood word production and recognition in Russian are opposite to English. J. Child Lang. 2020, 47, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.; Shelley-Tremblay, J.; Knapp, D.L. Measuring the influence of phonological neighborhood on visual word recognition with the N400: Evidence for semantic scaffolding. Brain Lang. 2020, 211, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatti, C.; Reynolds, M.G.; Besner, D. Neighborhood effects in reading aloud: New findings and new challenges for computational models. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2006, 32, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neergaard, K.D.; Xu, H.; German, J.S.; Huang, C.-R. Database of word-level statistics for Mandarin Chinese (DoWLS-MAN). Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hu, T.; Liu, S. Graded phonological neighborhood effects on lexical retrieval: Evidence from Mandarin Chinese. J. Mem. Lang. 2024, 137, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tong, X.; Shen, W. Influence of Lexical Tone Similarity on Spoken Word Recognition in Mandarin Chinese: Evidence From Eye Tracking. J. Speech Lang. Hear. R. 2023, 66, 3453–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, H. The roles of consonant, rime, and tone in mandarin spoken word recognition: An eye-tracking study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 740444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Bastiaanse, R.; Howard, D.; Alter, K. Representational level matters for tone-word recognition: Evidence from form priming. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2024, 77, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereno, J.A.; Lee, H. The Contribution of Segmental and Tonal Information in Mandarin Spoken Word Processing. Lang. Speech 2015, 58, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; O’Séaghdha, P.G.; Chen, T.M. The primacy of abstract syllables in Chinese word production. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2016, 42, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Chen, T.M. Word form encoding in mandarin Chinese typewritten word production: Evidence from the implicit priming task. Acta Psychol. 2013, 142, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Q. The roles of syllables and phonemes during phonological encoding in Chinese spoken word production: A topographic ERP study. Neuropsychologia 2020, 140, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Boshra, R.; Schmidtke, D.; Oralova, G.; Moro, A.L.; Service, E.; Connolly, J.F. Electrophysiological evidence for the integral nature of tone in Mandarin spoken word recognition. Neuropsychologia 2019, 131, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, K.D.; Huang, C.R. Graph theoretic approach to Mandarin syllable segmentation. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics (IsCLL-15), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 27–29 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Sharma, B. What is in the neighborhood of a tonal syllable? Evidence from auditory lexical decision in Mandarin Chinese. Proc. Linguist. Soc. Am. 2017, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, K.; Xu, H.; Huang, C. Database of Mandarin neighborhood statistics. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2016, Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016; pp. 4032–4036. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, K.D.; Huang, C.-R. Constructing the Mandarin Phonological Network: Novel Syllable Inventory Used to Identify Schematic Segmentation. Complexity 2019, 2019, 6979830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, J.L.; Elman, J.L. The TRACE Model of Speech Perception. Cogn. Psychol. 1986, 18, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidenberg, M.S.; McClelland, J.L. A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychol. Rev. 1989, 96, 523–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, M.; Sears, C.R.; Lupker, S.J. Masked priming with orthographic neighbors: A test of the lexical competition assumption. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2008, 34, 1236–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfetti, C.A.; Tan, L.H. The time course of graphic, phonological, and semantic activation in Chinese character identification. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1998, 24, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Peng, D.; Perfetti, C. The timing of graphic, phonological and semantic activation of high and low frequency Chinese characters: An ERP study. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2007, 17, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, J.X.; Kang, C.; Du, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S. P200 and phonological processing in Chinese word recognition. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 473, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jin, Z.; Qing, Z.; Wang, Z. The processing of phonological, orthographical, and lexical information of Chinese characters in sentence contexts: An ERP study. Brain Res. 2011, 1372, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutas, M.; Federmeier, K.D. Thirty years and counting: Finding meaning in the N400 component of the event-related brain potential (ERP). Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 621–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Kliegl, R.; Vasishth, S.; Baayen, H. Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.04967. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Plaut, D.C.; McClelland, J.L.; Seidenberg, M.S.; Patterson, K. Understanding normal and impaired word reading: Computational principles in quasi-regular domains. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 56–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harm, M.W.; Seidenberg, M.S. Computing the meanings of words in reading: Cooperative division of labor between visual and phonological processes. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 662–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pexman, P.M.; Lupker, S.J.; Reggin, L.D. Phonological Effects in Visual Word Recognition: Investigating the Impact of Feedback Activation. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2002, 28, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Schmidt, S.; Canseco-Gonzalez, E. Who do you love, your mother or your horse? An event-related brain potential analysis of tone processing in Mandarin Chinese. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2004, 33, 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Large PND | Small PND | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample character | lao4-酪 (cheese) | gou3-狗 (dog) | |

| LogCHR | 3.46 (0.65) | 3.57 (0.52) | |

| Strokes | 8.63 (2.01) | 8.65 (2.29) | |

| PND | 213.12 (23.14) | 119.23 (31.78) *** | |

| Neighborhood type | tone-edit | lao2 | gou4 |

| constituent-edit | lüe4 | gai3 | |

| Pinyin length | tone-edit | 3.78 (0.61) | 3.62 (0.61) |

| constituent-edit | 3.73 (0.69) | 3.93 (0.64) | |

| Consitituent_Edit | Tone_Edit Neighbor | |

|---|---|---|

| PND | (e.g., lüe4-酪) (cheese) | (e.g., lao2-酪) (cheese) |

| Large | 551 (0.993) | 572 (0.986) |

| Small | 558 (0.984) | 571 (0.977) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W. Phonological Neighborhood Density and Type Modulate Visual Recognition of Mandarin Chinese: Evidence from Monosyllabic Words. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121304

Jiao Z, Zhou X, Chen W. Phonological Neighborhood Density and Type Modulate Visual Recognition of Mandarin Chinese: Evidence from Monosyllabic Words. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121304

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiao, Zhongyan, Xianhui Zhou, and Wenjun Chen. 2025. "Phonological Neighborhood Density and Type Modulate Visual Recognition of Mandarin Chinese: Evidence from Monosyllabic Words" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121304

APA StyleJiao, Z., Zhou, X., & Chen, W. (2025). Phonological Neighborhood Density and Type Modulate Visual Recognition of Mandarin Chinese: Evidence from Monosyllabic Words. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121304