Complications and Ethical Challenges in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Complications of Neurosurgery in Psychiatric Disorders

3. Surgical and Vascular Complications

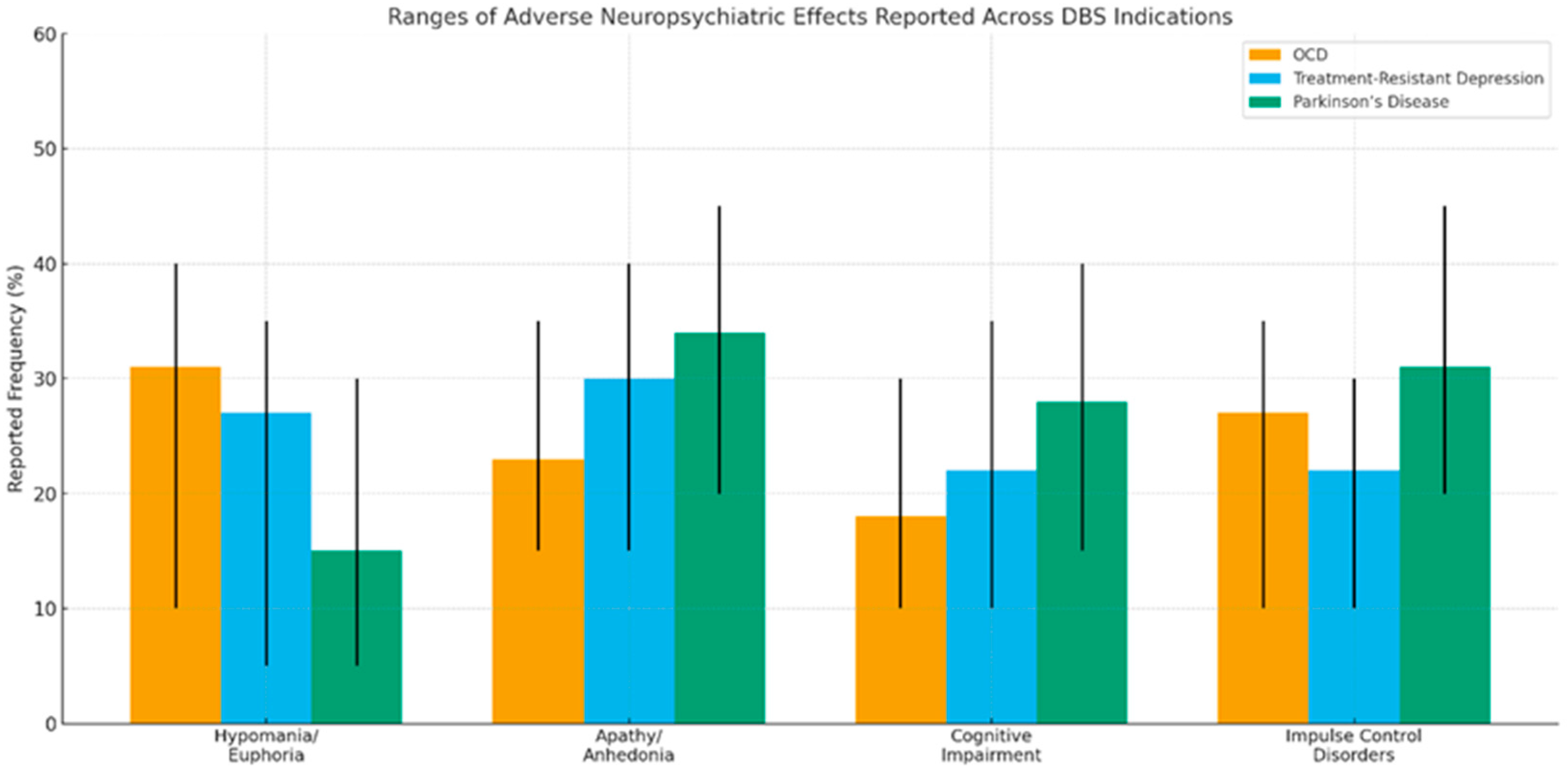

4. Cognitive and Behavioral Complications of DBS in Psychiatric Disorders

4.1. Cognitive Impairments

4.2. Behavioral and Emotional Changes

4.2.1. Episodes of Hypomania and Euphoria

4.2.2. Impulse Control Disorders

4.2.3. Changes in Personality and Identity

5. Ethical and Scientific Considerations in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruz, S.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; González-Domenech, P.; Díaz-Atienza, F.; Martínez-Ortega, J.M.; Jiménez-Fernández, S. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauerle, L.; Palmer, C.; Salazar, C.A.; Larrew, T.; Kerns, S.E.; Short, E.B.; George, M.S.; Rowland, N.C. Neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders: Reviewing the past and charting the future. Neurosurg. Focus 2023, 54, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, F.L.; Widge, A.S.; Riva-Posse, P.; Malone, D.A.; Okun, M.S.; Shanechi, M.M.; Foote, K.D.; Lisanby, S.H.; Ankudowich, E.; Chivukula, S.; et al. Future directions in psychiatric neurosurgery. Brain Stimul. 2023, 16, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Floden, D.; Gross, R.E. Neurosurgical neuromodulation therapy for psychiatric disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Kabotyanski, K.E.; Hirani, S.; Liu, T.; Naqvi, Z.; Giridharan, N.; Hasen, M.; Provenza, N.R.; Banks, G.P.; Mathew, S.J.; et al. Efficacy of deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2024, 9, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D.D.; Rezai, A.R.; Carpenter, L.L.; Howland, R.H.; Bhati, M.T.; O’rEardon, J.P.; Eskandar, E.N.; Baltuch, G.H.; Machado, A.D.; Kondziolka, D.; et al. A randomized sham-controlled trial of deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for chronic treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 78, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzheimer, P.E.; Husain, M.M.; Lisanby, S.H.; Taylor, S.F.; Whitworth, L.A.; McClintock, S.; Slavin, K.V.; Berman, J.; McKhann, G.M.; Patil, P.G.; et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A multisite, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergfeld, I.O.; Mantione, M.; Hoogendoorn, M.L.; Ruhe, H.G.; Notten, P.; van Laarhoven, J.; Visser, I.; Figee, M.; de Kwaasteniet, B.P.; Horst, F.; et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule for treatment-resistant depression: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, F.L.; Cristancho, M.A.; Yang, A.I. Deep Brain Stimulation of the Ventral Capsule/Ventral Striatum for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Decade of Clinical Follow-Up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 37487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, V.A.; Bewernick, B.H.; Kayser, S.; Kilian, H.; Boström, J.; Greschus, S.; Hurlemann, R.; Klein, M.E.; Spanier, S.; Sajonz, B.; et al. Superolateral branch of the medial forebrain bundle deep brain stimulation in major depression: Gateway trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl, A.; Aust, S.; Schneider, G.-H.; Visser-Vandewalle, V.; Horn, A.; Kühn, A.A.; Kuhn, J.; Bajbouj, M. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus in patients with treatment-resistant depression: A double-blinded randomized controlled study and long-term follow-up in eight patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewernick, B.H.; Kayser, S.; Sturm, V.; Schlaepfer, T.E. Long-term effects of nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: Evidence for sustained efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva-Posse, P.; Choi, K.S.; Holtzheimer, P.E.; Crowell, A.L.; Garlow, S.J.; Rajendra, J.K.; McIntyre, C.C.; Gross, R.E.; Mayberg, H.S. A connectomic approach for subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation surgery: Prospective targeting in treatment-resistant depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 23, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserri, S.; Segura-Amil, A.; Nowacki, A.; Debove, I.; Petermann, K.; Schäppi, L.; Preti, M.G.; Van De Ville, D.; Pollo, C.; Walther, S.; et al. Linking connectivity of deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens area with clinical depression improvements: A retrospective longitudinal case series. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 274, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott Laboratories. Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subcallosal Cingulate for Treatment-Resistant Depression (DBS-TRD); ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05678247; Abbott Laboratories: Abbott Park, IL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05678247 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Christopher, P.P.; Bucholz, K.K.; Howlett, G.G.; Shah, S.A. Enrolling in deep brain stimulation research for depression. AJOB Neurosci. 2012, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, C.J.; Segrave, R.A.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Richardson, K.E.; Racine, E.; Carter, A. “Nothing to lose, absolutely everything to gain”: Patient experiences of participating in a deep brain stimulation trial for treatment-resistant depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 755276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantzanou, M.; Korfias, S.; Panourias, I.; Sakas, D.E.; Karalexi, M.A. Deep Brain Stimulation-Related Surgical Site Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2021, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.K.; Kim, M.S.; Yoon, H.H.; Chung, S.J.; Jeon, S.R. The risk factors of intracerebral hemorrhage in deep brain stimulation: Does target matter? Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.-H.; Chang, K.W.; Park, S.H.; Chang, W.S.; Jung, H.H.; Chang, J.W. Complications After Deep Brain Stimulation: A 21-Year Experience in 426 Patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 819730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwens van der Vlis, T.A.M.; van de Veerdonk, M.M.G.H.; Ackermans, L.; Leentjens, A.F.G.; Janssen, M.L.F.; Kuijf, M.L.; Schruers, K.R.J.; Duits, A.; Gubler, F.; Kubben, P.; et al. Surgical and Hardware-Related Adverse Events of Deep Brain Stimulation: A Ten-Year Single-Center Experience. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, P.K.; Rai, N.; Das, D. Surgical and Hardware Complications of Deep Brain Stimulation-A Single Surgeon Experience of 519 Cases Over 20 Years. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2021, 25, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runia, N.; Mol, G.J.J.; Hillenius, T.; Hassanzadeh, Z.; Denys, D.A.J.P.; Bergfeld, I.O. Effects of deep brain stimulation on cognitive functioning in treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4585–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubert, C.; Hurlemann, R.; Bewernick, B.H.; Kayser, S.; Hadrysiewicz, B.; Axmacher, N.; Sturm, V.; Schlaepfer, T.E. Neuropsychological safety of nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for major depression: Effects of 12-month stimulation. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 12, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Perozzo, P.; Zibetti, M.; Crivelli, B.; Morabito, U.; Lanotte, M.; Cossa, F.; Bergamasco, B.; Lopiano, L. Chronic deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson’s disease: Effects on cognition, mood, anxiety and personality traits. Eur. Neurol. 2006, 55, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulla, M.; Thobois, S.; Lemaire, J.-J.; Schmitt, A.; Derost, P.; Broussolle, E.; Llorca, P.-M.; Durif, F. Manic behaviour induced by deep-brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: Evidence of substantia nigra implication? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Jeune, F.; Drapier, D.; Bourguignon, A.; Peron, J.; Mesbah, H.; Drapier, S.; Sauleau, P.; Haegelen, C.; Travers, D.; Garin, E.; et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson disease induces apathy: A PET study. Neurology 2009, 73, 1746–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeding, H.M.M.; EGoudriaan, A.; Foncke, E.M.J.; Schuurman, P.R.; Speelman, J.D.; Schmand, B. Pathological gambling after bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 78, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J.; Pycroft, L.; Maslen, H.; Aziz, T.; Savulescu, J. Evidence-Based Neuroethics, Deep Brain Stimulation and Personality—Deflating, but not Bursting, the Bubble. Neuroethics 2021, 14 (Suppl. S1), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J. No going back? Reversibility and why it matters for deep brain stimulation. J. Med. Ethics 2019, 45, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchón, J.M.; Real, E.; Alonso, P.; Aparicio, M.A.; Segalas, C.; Plans, G.; Luyten, L.; Brunfaut, E.; Matthijs, L.; Raymakers, S.; et al. A prospective international multi-center study on safety and efficacy of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 26, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforzini, L.; Worrell, C.; Kose, M.; Anderson, M.; Aouizerate, B.; Arolt, V.; Bauer, M.; Baune, B.T.; Blier, P.; Cleare, A.J.; et al. A Delphi-method-based consensus guideline for definition of treatment-resistant depression for clinical trials. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1286–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennabi, D.; Alaïli, N.; Yrondi, A.; Charpeaud, T.; Lancrenon, S.; De Las Cuevas, C.; Destouches, S.; Loundou, A.; Courtet, P.; Genty, J.B.; et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of treatment-resistant depression: French recommendations from experts, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology and the fondation FondaMental. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, L.; Polosan, M.; Jaafari, N.; Baup, N.; Welter, M.-L.; Fontaine, D.; du Montcel, S.T.; Yelnik, J.; Chéreau, I.; Arbus, C.; et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2121–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figee, M.; Vink, M.; de Geus, F.; Vulink, N.; Veltman, D.J.; Westenberg, H.; Denys, D. Dysfunctional reward circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar-Barrutia, L.; Real, E.; Segalás, C.; Bertolín, S.; Menchón, J.M.; Alonso, P. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review of worldwide experience after 20 years. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, H.; Hariz, M.; Visser-Vandewalle, V.; Zrinzo, L.; Coenen, V.A.; Sheth, S.A.; Greenberg, B.D.; Mallet, L.; Nuttin, B.; Ras-mussen, S.A.; et al. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): Emerging or estab-lished therapy? Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M.; Giacobbe, P.; Hamani, C.; Rizvi, S.J.; Kennedy, S.H.; Kolivakis, T.T.; Debonnel, G.; Sadikot, A.F.; Lam, R.W.; Howard, A.K.; et al. A multicenter pilot study of subcallosal cingulate area DBS for treatment- resistant depression. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 116, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewernick, B.H.; Hurlemann, R.; Matusch, A.; Kayser, S.; Grubert, C.; Hadrysiewicz, B.; Axmacher, N.; Lemke, M.; Cooper-Mahkorn, D.; Cohen, M.X.; et al. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, B.D.; Gabriels, L.A.; Malone, D.A., Jr.; Rezai, A.R.; Friehs, G.M.; Okun, M.S.; Shapira, N.A.; Foote, K.D.; Cosyns, P.R.; Kubu, C.S.; et al. DBS of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for OCD: Worldwide experience. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadway, J.M.; Holtzheimer, P.E.; Hilimire, M.R.; Parks, N.A.; DeVylder, J.E.; Mayberg, H.S.; Corballis, P.M. Frontal theta cordance predicts 6-month antidepressant response to subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1764–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holtzheimer, P.E.; Kelley, M.E.; Gross, R.E.; Filkowski, M.M.; Garlow, S.J.; Barrocas, A.; Wint, D.; Craighead, M.C.; Kozarsky, J.; Chismar, R.; et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denys, D.; Mantione, M.; Figee, M.; Munckhof, P.v.D.; Koerselman, F.; Westenberg, H.; Bosch, A.; Schuurman, R. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FORESEE III Study Group. Deep Brain Stimulation of the Superolateral Medial Forebrain Bundle (slMFB) for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Randomized Double-Blind Sham-Controlled Clinical Trial; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04021823; National Library of Medicine (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04021823 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Treu, S.; Barcia, J.A.; Torres, C.; Bierbrauer, A.; Gonzalez-Rosa, J.J.; Nombela, C.; Pineda-Pardo, J.A.; Torres, D.; Kunz, L.; Hellerstedt, R.; et al. Deep-brain stimulation of the human nucleus accumbens-medial septum enhances memory formation. Res. Sq. 2023, rs.3.rs-3476665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laseca-Zaballa, G.; Lubrini, G.; Periañez, J.A.; Simón-Martínez, V.; Martín Bejarano, M.; Torres-Díaz, C.; Martínez Moreno, N.; Álvarez-Linera, J.; Martínez Álvarez, R.; Ríos-Lago, M. Cognitive outcomes following functional neurosurgery in refractory OCD patients: A systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2023, 46, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, M.S.; Fernandez, H.H.; Wu, S.S.; Kirsch-Darrow, L.; Bowers, D.; Bova, F.; Suelter, M.; Jacobson, C.E.; Wang, X.; Gordon, C.W.; et al. Cognition and mood in Parkinson’s disease in subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation: The COMPARE trial. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 65, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Lozano, A.M.; Sime, E.; Lang, A.E. Long-term follow-up of thalamic deep brain stimulation for essential and parkinsonian tremor. Neurology 2003, 61, 1601–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voon, V.; Kubu, C.; Krack, P.; Houeto, J.L.; Tröster, A.I. Deep brain stimulation: Neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric issues. Mov Disord. 2006, 21 (Suppl. S14), S305–S327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeding, H.M.M.; Speelman, J.D.; Huizenga, H.M.; Schuurman, P.R.; Schmand, B. Predictors of cognitive and psychosocial outcome after STN DBS in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 82, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, Y.; Blokland, A.; Steinbusch, H.W.; Visser-Vandewalle, V. The functional role of the subthalamic nucleus in cognitive and limbic circuits. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 76, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxendale, S.; Thompson, P. Defining meaningful postoperative change in epilepsy surgery patients: Measuring the unmeasurable? Epilepsy Behav. 2005, 6, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmstaedter, C.; Reuber, M.; Elger, C.C.E. Interaction of cognitive aging and memory deficits related to epilepsy surgery. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 52, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamiwka, L.D.; Wirrell, E.C.; Sherman, E.M.; Slick, D.J.; Connolly, M.B.; Wiebe, S. Long-term seizure outcomes after pediatric epilepsy surgery: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Neurology 2015, 84, 571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenschurz-Schmidt, D.J.; Calcagnini, G.; Dipasquale, O.; Jackson, J.B.; Medina, S.; O’dAly, O.; O’Muircheartaigh, J.; Rubio, A.d.L.; Williams, S.C.R.; McMahon, S.B.; et al. Linking pain sensation to the autonomic nervous system: The role of the anterior cingulate and periaqueductal gray resting-state networks. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, L.B.; Holtzheimer, P.E.; Hoop, J.G.; Mayberg, H.S.; Appelbaum, P.S. Ethical Issues in Deep Brain Stimulation Research for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Focus on Risk and Consent. AJOB Neurosci. 2011, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechtman, M. Philosophical reflections on narrative and deep brain stimulation. J. Clin. Ethics 2010, 21, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, F.; Viaña, J.N.M.; Ineichen, C. Deflating the BDBS causes personality changes bubble. Neuroethics 2021, 14 (Suppl. S1), S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widge, A.S.; Zhang, F.; Gosai, A.; Papadimitrou, G.; Wilson-Braun, P.; Tsintou, M.; Palanivelu, S.; Noecker, A.M.; McIntyre, C.C.; O’dOnnell, L.; et al. Patient-specific connectomic models correlate with, but do not reliably predict, outcomes in deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 47, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Complication | Incidence (%) | Main Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) | 2.2–2.6% | Increased risk with elevated intraoperative systolic blood pressure [31] |

| Hardware-related infections | 0–9.95% | Higher risk in psychiatry due to compulsive manipulation and protocol duration [20,21] |

| Hardware complications | Up to 6.7% | Electrode migration, cable fracture, IPG malfunction [20,22,24] |

| Surgical reinterventions | Up to 6.3% | Due to infections, IPG failure, or technical complications [21,22] |

| Type of Effect | Main Characteristics | Frequency/Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairments | Decreased verbal fluency and processing speed | Potentially reversible with parameter adjustments. Common with nucleus accumbens stimulation [35] |

| Hypomania/euphoria | Impulsivity, hyperactivity, impaired social judgment | Reversible with parameter changes. Ventral internal capsule or nucleus accumbens stimulation [36] |

| Apathy/anhedonia | Reduced emotional reactivity | Reversible with parameter changes. Excessive stimulation of limbic structures [20,22,23,24,25] |

| Impulse control disorders | Compulsive shopping, hypersexuality, gambling | Reversible with parameter changes. Stimulation of reward system structures [20,22,23,24,25] |

| Personality/identity changes | Feeling “different,” altered sense of self | Requires rigorous ethical evaluation [20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres Díaz, C.V.; Gracia, J.L.A.; Lara Almunia, M.; Granados, G.O.; García, M.N.; Rivas, P.P.; De Pedro, M.D.A.; De Sola, R.G.; Moleón-Ruiz, Á. Complications and Ethical Challenges in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121303

Torres Díaz CV, Gracia JLA, Lara Almunia M, Granados GO, García MN, Rivas PP, De Pedro MDA, De Sola RG, Moleón-Ruiz Á. Complications and Ethical Challenges in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121303

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres Díaz, Cristina V., Joaquín Luis Ayerbe Gracia, Mónica Lara Almunia, Gonzalo Olivares Granados, Marta Navas García, Paloma Pulido Rivas, Marta Del Alamo De Pedro, Rafael García De Sola, and Álvaro Moleón-Ruiz. 2025. "Complications and Ethical Challenges in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121303

APA StyleTorres Díaz, C. V., Gracia, J. L. A., Lara Almunia, M., Granados, G. O., García, M. N., Rivas, P. P., De Pedro, M. D. A., De Sola, R. G., & Moleón-Ruiz, Á. (2025). Complications and Ethical Challenges in Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Disorders. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121303