One System, Two Rules: Asymmetrical Coupling of Speech Production and Reading Comprehension in the Trilingual Brain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Objectives

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Participants

Language Acquisition and Proficiency Patterns

2.2.2. Materials

2.2.3. Design

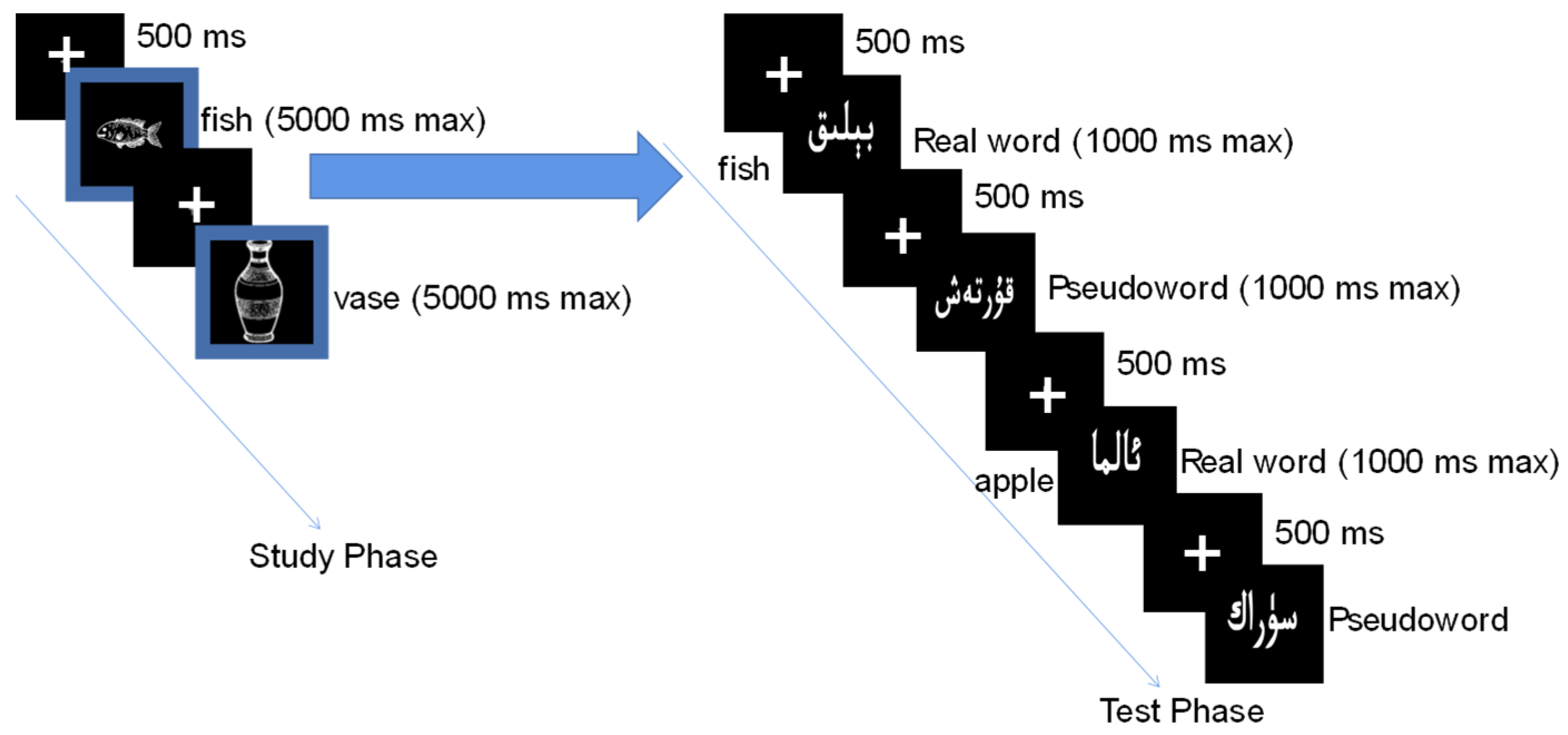

2.2.4. Procedure

2.2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

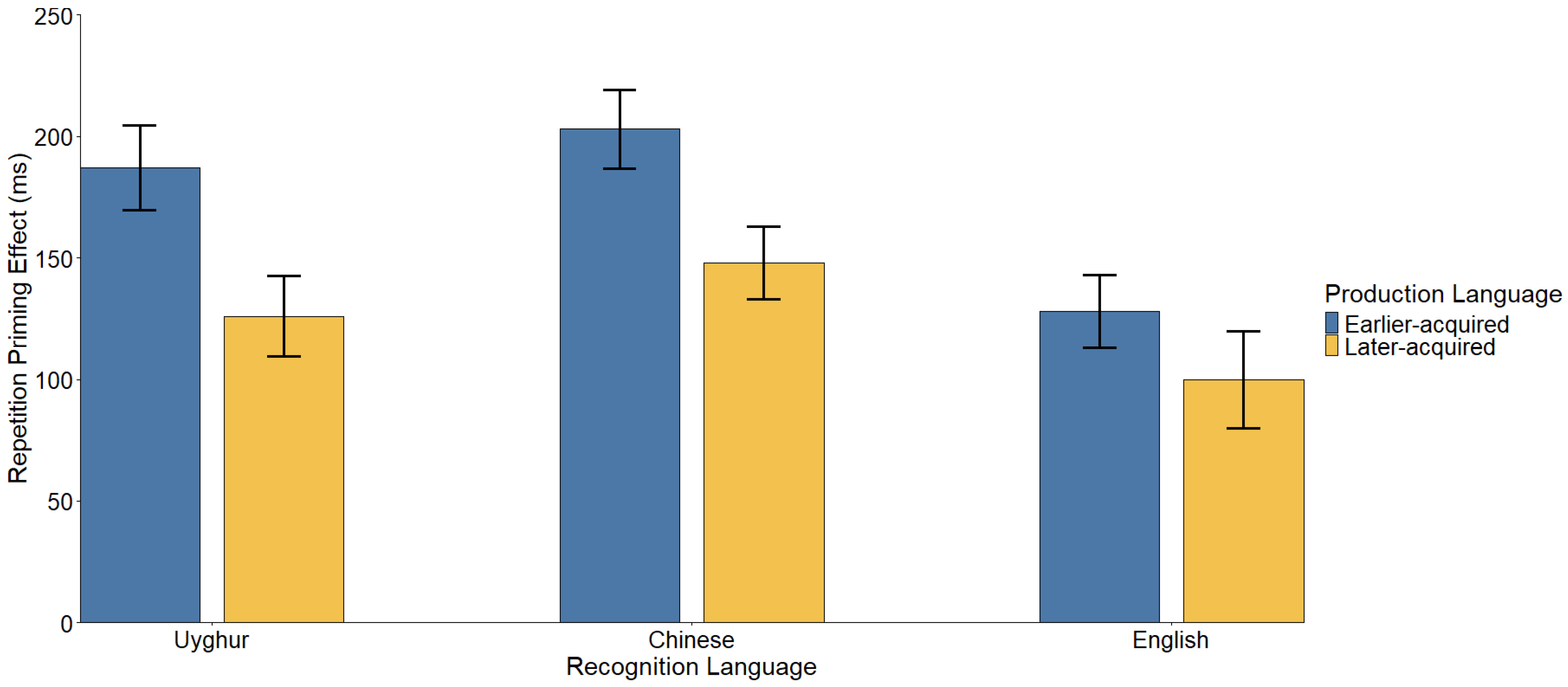

3.1. Evidence for Cross-Modal Facilitation (Addressing RQ1)

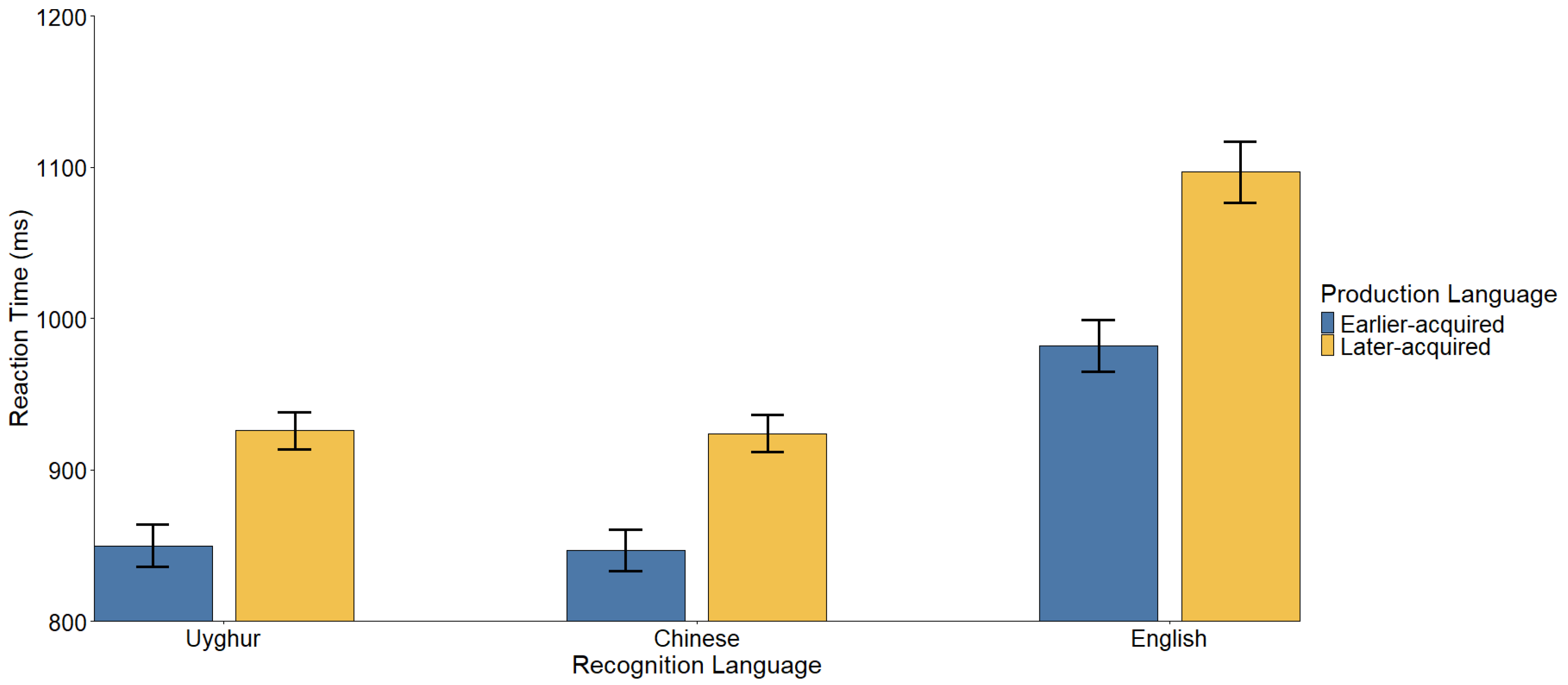

3.2. Baseline Efficiencies of Production and Recognition

3.3. Drivers of Asymmetry: Testing the Two Hypotheses (Addressing RQ2)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Integrated and Asymmetrical Architecture of the Trilingual Lexicon (Addressing RQ1)

4.2. Resolving the Theoretical Tension: AoA Primacy vs. Social Usage (Addressing RQ2)

4.2.1. The Power of the Prime: Support for AoA Primacy

4.2.2. The Receptivity of the Target: Support for Social Usage Frequency

4.3. Methodological Contributions: The Utility of the Trilingual Design

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

| Item | English Real | English Pseudo | Uyghur Real | Uyghur Pseudo | Chinese Real | Chinese Pseudo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | apple | opple | ئالما | ئارنا | 苹果 | 客封 |

| 2 | baby | bavy | بوۋاق | بوماق | 婴儿 | 背昨 |

| 3 | ball | bazz | توپ | تود | 球 |  |

| 4 | bed | beb | كارىۋات | كالىۋات | 床 |  |

| 5 | bird | birt | قۇش | قۇن | 鸟 |  |

| 6 | boat | bost | كېمە | كېسە | 船 |  |

| 7 | book | boof | كىتاب | كىتات | 书 |  |

| 8 | bridge | brudge | كۆۋرۈك | كۆمرۈك | 桥 |  |

| 9 | cake | cabe | تورت | تورس | 蛋糕 | 科映 |

| 10 | camel | camet | تۆگە | تۆنە | 骆驼 | 界冒 |

| 11 | candle | canble | شام | شاس | 蜡烛 | 律甚 |

| 12 | cat | caz | مۈشۈك | مۈكۈك | 猫 |  |

| 13 | chair | chail | ئورۇندۇق | ئوسۇندۇق | 椅子 | 炭括 |

| 14 | clock | closk | سائەت | سائەك | 钟 |  |

| 15 | cloud | cloup | بۇلۇت | بۇلۇس | 云 |  |

| 16 | cow | cof | كالا | كانا | 牛 |  |

| 17 | dog | deg | ئىت | ئىب | 狗 |  |

| 18 | door | doop | ئىشىك | ئىشىن | 门 |  |

| 19 | egg | ekk | تۇخۇم | تۇسۇم | 鸡蛋 | 柏耐 |

| 20 | finger | fanger | بارماق | بارناق | 手指 | 盆度 |

| 21 | fire | fibe | ئوت | ئود | 火 |  |

| 22 | fish | fisk | بېلىق | بېرىق | 鱼 |  |

| 23 | flower | flowet | گۈل | گول | 花 |  |

| 24 | glasses | glesses | كۆزەينەك | كۆزەيمەك | 眼镜 | 牧映 |

| 25 | hand | hant | قول | قوس | 手 |  |

| 26 | horse | harse | ئات | ئاج | 马 |  |

| 27 | leaf | leab | يوپۇرماق | يوپۇرساق | 叶子 | 查耐 |

| 28 | mirror | mirron | ئەينەك | ئەيمەك | 镜子 | 牵亭 |

| 29 | monkey | monney | مايمۇن | مايسۇن | 猴 |  |

| 30 | mountain | mountern | تاغ | تاف | 山 |  |

| 31 | nose | nuse | بۇرۇن | بۇرۇم | 鼻 |  |

| 32 | onion | onior | پىياز | پىياس | 洋葱 | 览侵 |

| 33 | pear | peaf | نەشپۈت | نەشسۈت | 梨 |  |

| 34 | ladder | labber | شوتا | شونا | 梯子 | 宣盾 |

| 35 | bone | bome | سۆڭەك | سۆمەك | 骨头 | 虽柱 |

| 36 | toilet | toilek | ئۇنىتاز | ئۇنىكاز | 马桶 | 枯泳 |

| 37 | dress | driss | كۆينەك | كۆيبەك | 裙子 | 某苦 |

| 38 | pencil | pencin | قېرىنداش | قېرىنلاش | 铅笔 | 南抹 |

| 39 | rabbit | rabbik | توشقان | توشمان | 兔子 | 泉拆 |

| 40 | ruler | rulet | سىزغۇچ | سىزغۇپ | 尺子 | 盾松 |

| 41 | snake | snate | يىلان | يىمان | 蛇 |  |

| 42 | tiger | tider | يولۋاس | يولماس | 老虎 | 架析 |

| 43 | table | taple | شىرە | شىسە | 桌子 | 眉昆 |

| 44 | tree | trep | دەرەخ | دەرەس | 树 |  |

| 45 | sun | sut | قۇياش | قۇيام | 太阳 | 甚牧 |

| 46 | phone | phome | تېلېفون | تېلېتۇن | 电话 | 析柳 |

| 47 | window | windom | دېرىزە | دېرىسە | 窗户 | 环柔 |

| 48 | milk | misk | سۈت | سۈك | 牛奶 | 奔段 |

Appendix B. Sample Picture Stimuli Used in the Production Phase

| English Naming Condition | Chinese Naming Condition | Uyghur Naming Condition |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| mirror | 马桶 | شوتا |

|  |  |

| baby | 骆驼 | كۆينەك |

|  |  |

| monkey | 骨头 | تۇخۇم |

Appendix C. Full Statistical Model Results

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 928.2 | 7.41 | 141 | 126.52 | <0.001 |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Lexical Status at Test Phase (studied vs. unstudied words) | −148.6 | 4.42 | 126 | −35.5 | <0.001 |

| Production Language at study phase (later-acquired language vs. earlier-acquired language) | 89.18 | 14.83 | 131 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Recognition Language (L2 vs. L1) | −2.99 | 4.54 | 138 | −0.897 | 0.37 |

| Recognition Language (L3 vs. L1) | 151.68 | 16.14 | 137 | 9.33 | <0.001 |

| Recognition Language (L2 vs. L3) | −154.7 | 16.06 | 135 | −9.63 | <0.001 |

| Two-Way Interactions | |||||

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L1) | −18.65 | 7.82 | 136 | −2.573 | 0.022 |

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Recognition Language (L3 vs. L1) | 42.3 | 10.47 | 138 | 4.73 | <0.001 |

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L3) | −61 | 10.17 | 127 | −5.34 | <0.001 |

| Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L1) | 1.92 | 9.08 | 138 | 0.137 | 0.891 |

| Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L3 vs. L1) | 39.51 | 12.28 | 138 | 1.21 | 0.226 |

| Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L3) | −37.6 | 12.13 | 135 | −1.18 | 0.239 |

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Production Language at study phase (earlier-acquired language vs. later-acquired language) | 48.04 | 8.84 | 126 | 5.72 | <0.001 |

| Three-Way Interactions | |||||

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L1) | −6.65 | 15.64 | 138 | −0.261 | 0.794 |

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L3 vs. L1) | −33.51 | 20.94 | 138 | 1.5 | 0.209 |

| Lexical Status at Test Phase × Production Language at study phase × Recognition Language (L2 vs. L3) | 26.86 | 20.34 | 127 | 1.26 | 0.136 |

References

- Kroll, J.F.; Bobb, S.C.; Misra, M.; Guo, T. Language selection in bilingual speech: Evidence for inhibitory processes. Acta Psychol. 2008, 128, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.; Van Heuven, W.J. The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2002, 5, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Peng, D. Event-related potential evidence for parallel activation of two languages in bilingual speech production. NeuroReport 2006, 17, 1757–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, J.F.; Stewart, E. Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. J. Mem. Lang. 1994, 33, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.F.; van Hell, J.G.; Tokowicz, N.; Green, D. WThe Revised Hierarchical Model: A critical review and assessment. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2010, 13, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Santesteban, M. Lexical access in bilingual speech production: Evidence from language switching in highly proficient bilinguals and L2 learners. J. Mem. Lang. 2004, 50, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 1998, 1, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W.; Abutalebi, J. Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 25, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.; Wahl, A.; Buytenhuijs, F.; VAN Halem, N.; Al-Jibouri, Z.; De Korte, M.; Rekké, S. Multilink: A computational model for bilingual word recognition and word translation. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2019, 22, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M.; Kleinman, D.; Gollan, T.H. Which bilinguals reverse language dominance and why? Cognition 2020, 204, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouch-Orozco, A.; Alonso, J.G.; Rothman, J. Individual differences in bilingual word recognition: The role of experiential factors and word frequency in cross-language lexical priming. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2021, 42, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford University Press. Quick Placement Test: Paper and Pen Test; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, A.L.; Tree, J.E.F. A quick, gradient bilingual dominance scale. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2009, 12, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J. Defining multilingualism. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2013, 33, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bot, K.; Jaensch, C. What is special about L3 processing? Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2015, 18, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardel, C.; Falk, Y. The role of the second language in third language acquisition: The case of Germanic syntax. Second. Lang. Res. 2007, 23, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J. Linguistic and cognitive motivations for the Typological Primacy Model (TPM) of third language (L3) transfer: Timing of acquisition and proficiency considered. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2015, 18, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, D.; Aronin, L. What is multilingualism. In Twelve Lectures in Multilingualism; Multilingual Matters & Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. How do L3 words find conceptual parasitic hosts in typologically distant L1 or L2? Evidence from a cross-linguistic priming effect. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2020, 23, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, J.; Midgley, K.; Holcomb, P.J. Chapter 14. Re-thinking the bilingual interactive-activation model from a developmental perspective (BIA-d). In Language Acquisition Across Linguistic and Cognitive Systems; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A.; Mak, L.; Chahi, A.K.; Bialystok, E. The language and social background questionnaire: Assessing degree of bilingualism in a diverse population. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J. Cogn. 2019, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoschuk, B.; Ferreira, V.S.; Gollan, T.H. When a seven is not a seven: Self-ratings of bilingual language proficiency differ between and within language populations. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2019, 22, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T.H.; Weissberger, G.H.; Runnqvist, E.; Montoya, R.I.; Cera, C.M. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish–English bilinguals. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2012, 15, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, A.; Jacobsen, T.; D’AMico, S.; Devescovi, A.; Andonova, E.; Herron, D.; Lu, C.C.; Pechmann, T.; Pléh, C.; Wicha, N.; et al. A new on-line resource for psycholinguistic studies. J. Mem. Lang. 2004, 51, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keuleers, E.; Brysbaert, M. Wuggy: A multilingual pseudoword generator. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-Y.; Tseng, C.-C.; Perfetti, C.A.; Chen, H.-C. Development and validation of a Chinese pseudo-character/non-character producing system. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, R. Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R.H.; Milin, P. Analyzing reaction times. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.J.; Levy, R.; Scheepers, C.; Tily, H.J. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 2013, 68, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, F.E. An approximate distribution of estimates of variance components. Biom. Bull. 1946, 2, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, S.G. Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenth, R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. ‘emmeans’: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means; Version 185, R Package; R: Wien, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert, M.; Stevens, M. Power analysis and effect size in mixed effects models: A tutorial. J. Cogn. 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, C.; Meir, N. Dynamics of competition and co-activation in trilingual lexical processing: An eye-tracking study. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, S.; Mosca, M.; Stutter Garcia, A. The role of crosslinguistic influence in multilingual processing: Lexicon versus syntax. Lang. Learn. 2021, 71 (Suppl. S1), 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivey, M.J.; Marian, V. Cross talk between native and second languages: Partial activation of an irrelevant lexicon. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Cairang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, C. Examining non-task language effect on production-based language switching: Evidence from Tibetan-Chinese-English trilinguals. Int. J. Biling. 2023, 27, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, L.S.; Vulchanova, M.; Pathak, P.; Mishra, R.K. Trilingual parallel processing: Do the dominant languages grab all the attention? Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2025, 28, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, R.; Kroll, J.F. Matching words to concepts in two languages: A test of the concept mediation model of bilingual representation. Mem. Cogn. 1995, 23, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C. Perceptual representations in L1, L2 and L3 comprehension: Delayed sentence–picture verification. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2020, 49, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulík, S.; Carrasco-Ortiz, H.; Amengual, M. Phonological activation of first language (Spanish) and second language (English) when learning third language (Slovak) novel words. Int. J. Biling. 2019, 23, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, V.; Titone, D. The effects of word frequency and word predictability during first-and second-language paragraph reading in bilingual older and younger adults. Psychol. Aging 2017, 32, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J.W.; Titone, D. Characterizing the social diversity of bilingualism using language entropy. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2020, 23, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J.W.; Titone, D. Bilingualism: A neurocognitive exercise in managing uncertainty. Neurobiol. Lang. 2021, 2, 464–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J.W.; Kousaie, S.; Gilbert, A.C.; Grant, A.; Giroud, N.; Coulter, K.; Klein, D.; Baum, S.; Phillips, N.; Titone, D. Bilingual language experience as a multidimensional spectrum: Associations with objective and subjective language proficiency. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2021, 42, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, A.; Marian, V. The bilingual language interaction network for comprehension of speech. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2013, 16, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijewska, A. The influence of semantic bias on triple non-identical cognates during reading: Evidence from trilinguals’ eye movements. Second. Lang. Res. 2023, 39, 1235–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Mok, P. Cross-linguistic influences on the production of third language consonant clusters by L1 Cantonese–L2 English–L3 German trilinguals. Int. J. Multiling. 2024, 21, 1700–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otwinowska, A. Cross-linguistic influence and language co-activation in acquiring L3 words: What empirical evidence do we have so far? Second. Lang. Res. 2024, 40, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrelli, J.; Iverson, M. Why do learners overcome non-facilitative transfer faster from an L2 than an L1? The cumulative input threshold hypothesis. Int. J. Multiling. 2024, 21, 1594–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | L1 Uyghur | L2 Chinese | L3 English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of acquisition (years) M (SD) | 1.24 (1.81) | 6.14 (3.27) | 12.34 (3.41) |

| Residential Exposure (years) M (SD) | 13.9 (2.29) | 16.8 (2.16) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of Use (years) M (SD) | 19.02 (2.61) | 13.94 (3.28) | 8.00 (3.76) |

| Frequency of Use (Home; 0–5) M (SD) | 4.10 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.44) | 0.20 (0.41) |

| Frequency of Use (Social; 0–5) M (SD) | 0.69 (0.29) | 4.29 (0.46) | 0.02 (0.40) |

| Self-ratings of proficiency | |||

| Speaking M (SD) | 9.51 (1.23) | 9.13 (1.19) | 5.54 (1.61) |

| Listening M (SD) | 9.08 (1.21) | 8.89 (1.06) | 5.06 (1.20) |

| Reading M (SD) | 8.56 (1.11) | 7.97 (1.69) | 5.92 (1.58) |

| Writing M (SD) | 7.28 (1.12) | 8.79 (1.99) | 5.60 (1.87) |

| MINT (0–68) score M (SD) | 65.0 (1.92) | 64.8 (2.10) | 49.8 (2.70) |

| Learning contexts | |||

| Home-only Learning N (%) | 88 (61.11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| School-only Learning N (%) | 0 (0%) | 122 (84.72%) | 144 (100%) |

| both N (%) | 56 (38.89%) | 22 (15.27%) | 0 (0%) |

| Medium-of-instruction | |||

| Uyghur N (%) | n/a | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chinese N (%) | n/a | 144 (100%) | 144 (100%) |

| Uyghur | Chinese | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earlier-acquired language | |||

| Unstudied words M (SE) | 944 (11.26) | 948 (10.46) | 1046 (10.58) |

| Studied words M (SE) | 757 (12.36) | 745 (11.46) | 918 (10.29) |

| Repetition priming effect M (SE) | 187 (17.5) | 203 (16.2) | 128 (14.96) |

| Later-acquired language | |||

| Unstudied words M (SE) | 989 (12.02) | 998 (11.28) | 1147 (14.12) |

| Studied words M (SE) | 863 (11.62) | 850 (10.58) | 1047 (13.06) |

| Repetition priming effect M (SE) | 126 (16.44) | 148 (14.96) | 100 (19.98) |

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 928.2 | 7.41 | 141 | 126.52 | <0.001 |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Lexical Status (Studied vs. Unstudied) | −148.6 | 4.42 | 126 | −35.5 | <0.001 |

| Production Language (Earlier vs. Later) | 89.18 | 14.83 | 131 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Recognition Language (L2 vs. L1) | −2.99 | 4.54 | 138 | −0.897 | 0.37 |

| Recognition Language (L3 vs. L1) | 151.68 | 16.14 | 137 | 9.33 | <0.001 |

| Critical Interactions | |||||

| Lexical Status × Production Lang (Early vs. Late) | 48.04 | 8.84 | 126 | 5.72 | <0.001 |

| Lexical Status × Recognition Lang (L2 vs. L1) | −18.65 | 7.82 | 136 | −2.573 | 0.022 |

| Lexical Status × Recognition Lang (L3 vs. L1) | 42.3 | 10.47 | 138 | 4.73 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, R. One System, Two Rules: Asymmetrical Coupling of Speech Production and Reading Comprehension in the Trilingual Brain. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121288

Wang Y, Meng Y, Yang Q, Wang R. One System, Two Rules: Asymmetrical Coupling of Speech Production and Reading Comprehension in the Trilingual Brain. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121288

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuanbo, Yingfang Meng, Qiuyue Yang, and Ruiming Wang. 2025. "One System, Two Rules: Asymmetrical Coupling of Speech Production and Reading Comprehension in the Trilingual Brain" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121288

APA StyleWang, Y., Meng, Y., Yang, Q., & Wang, R. (2025). One System, Two Rules: Asymmetrical Coupling of Speech Production and Reading Comprehension in the Trilingual Brain. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121288