Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Altered Language Processing System Connectivity and Its Implications on Language Comprehension and Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Aims of the Study

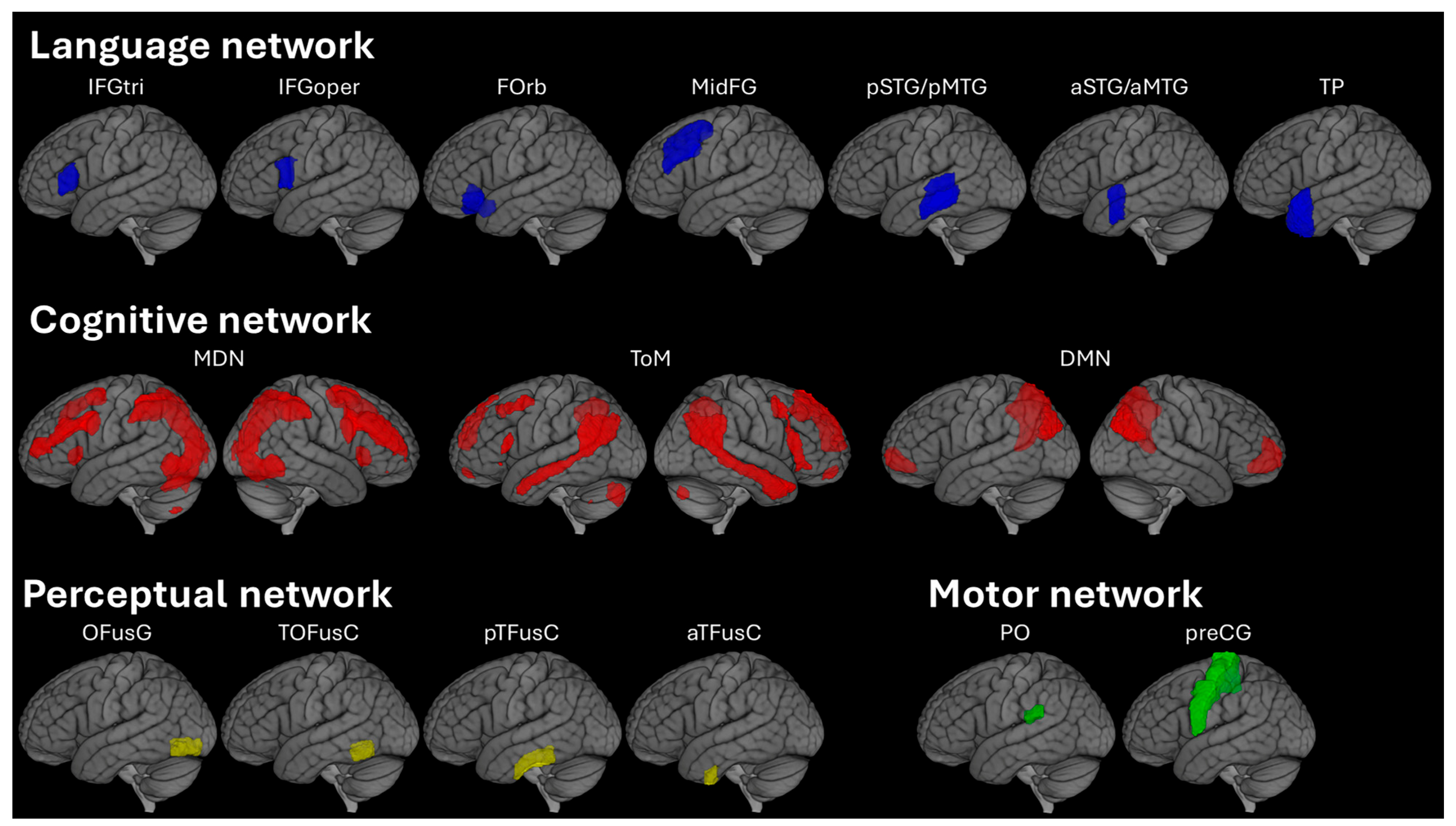

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Clinical Testing

2.3. Image Acquisition

2.4. Image Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

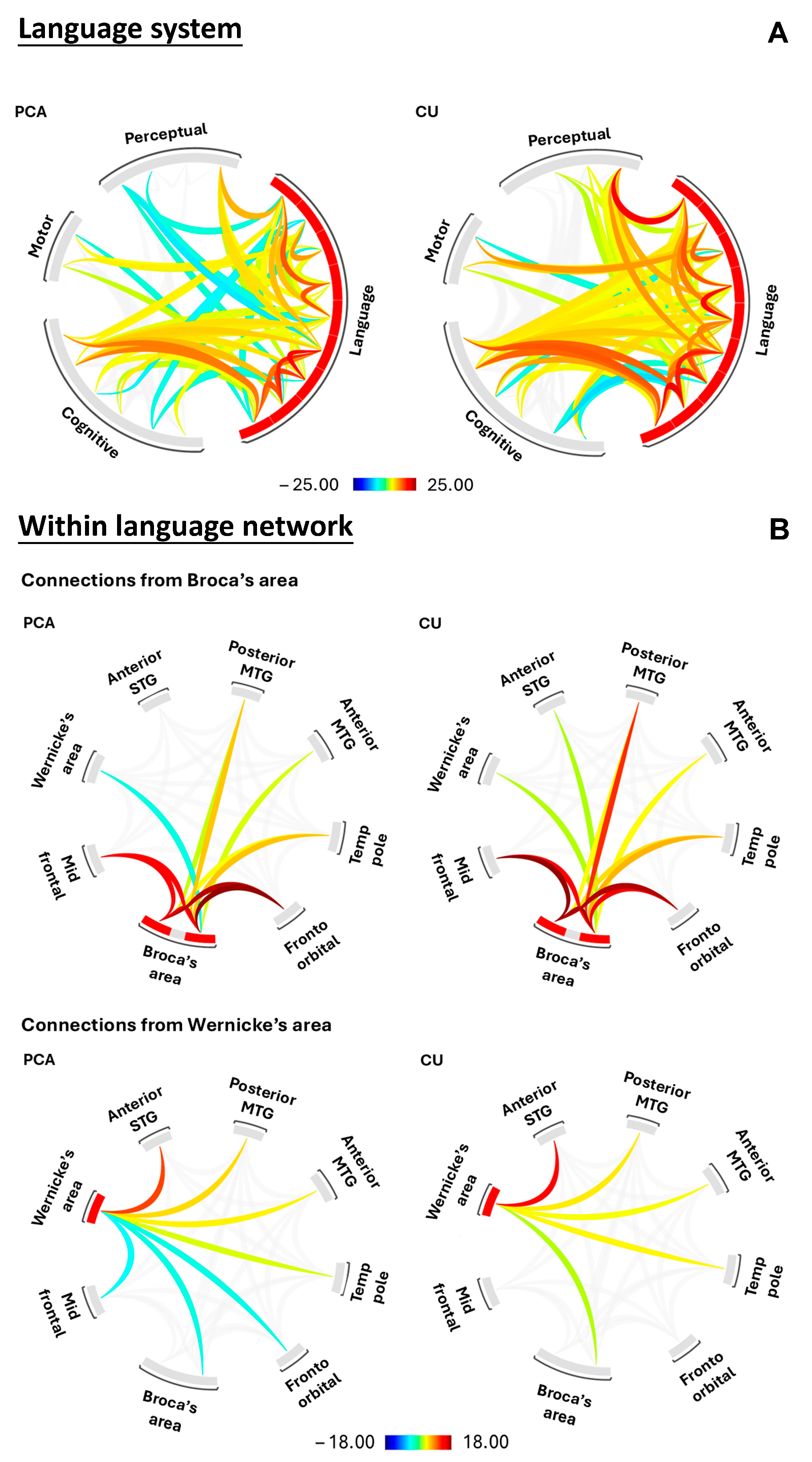

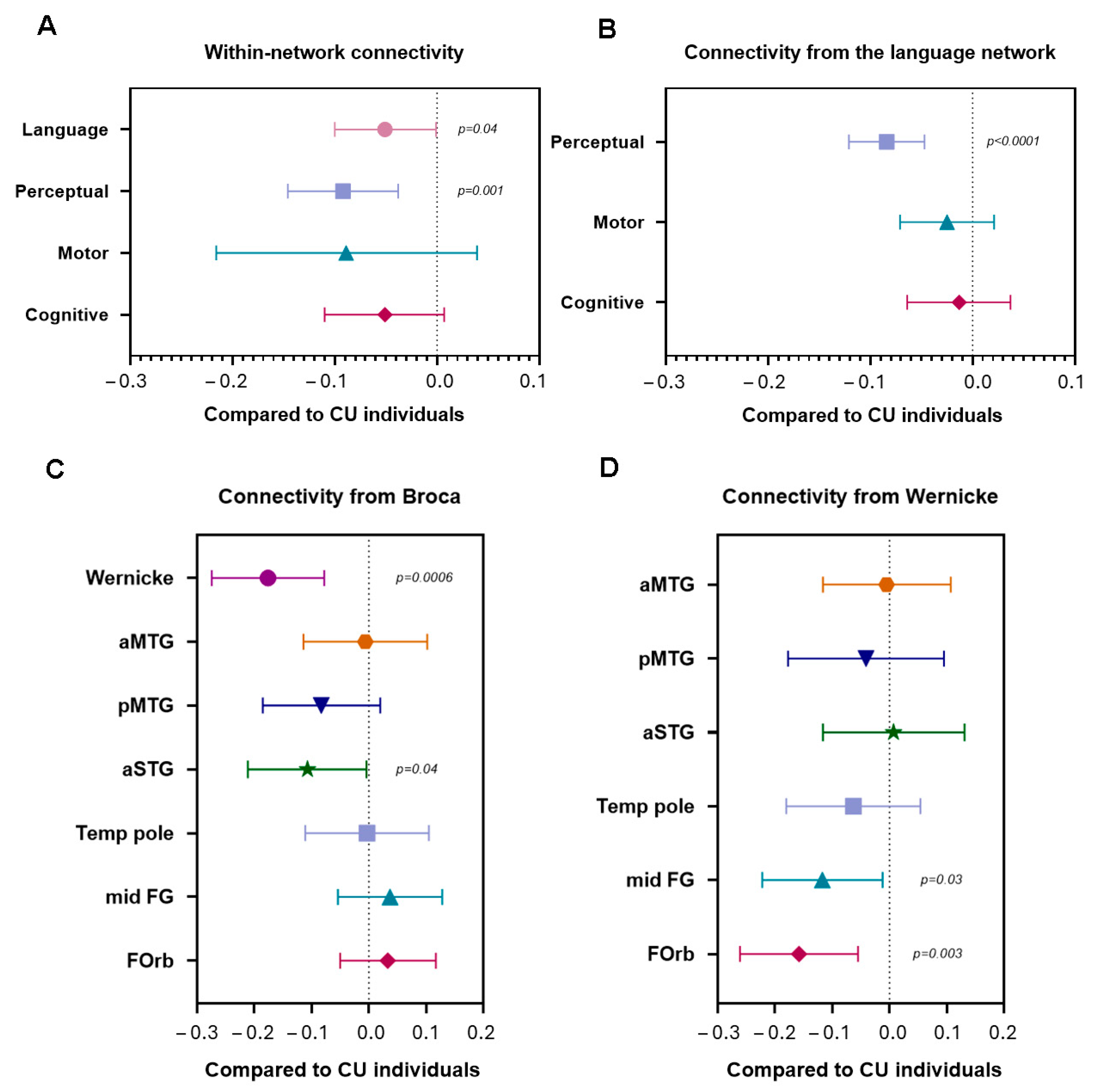

3.2. Within- and Between-Network Connectivity (Aim 1)

3.2.1. Network Level: Language Processing System

3.2.2. Regional Level: Within the Language Network

3.3. Relationship Between Clinical Scores and Language System Connectivity (Aim 2)

3.3.1. Network Level: Language Processing System

3.3.2. Regional Level: Within the Language Network

3.4. Effect of Gray Matter Volumes on Language System Connectivity (Aim 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional Connectivity Breakdown in the Language Processing System

4.2. Relationship Between Clinical Scores, Gray Matter Volume and Language System Connectivity

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| CU | Cognitively Unimpaired individuals |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MPRAGE | Magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo |

| NRG | Neurodegenerative Research Group |

| PiB | Pittsburgh Compound B |

| PCA | Posterior Cortical Atrophy |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| ROI | Regions of Interest |

| rsfMRI | Resting state functional MRI |

| BNT-SF | 15-item Boston Naming Test- Short form |

| BDAE | Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Exam |

| PPT | Pyramids and Palm Trees |

| VOSP | Visual Object and Space Perception Battery |

References

- Crutch, S.J.; Schott, J.M.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Murray, M.; Snowden, J.S.; van der Flier, W.M.; Dickerson, B.C.; Vandenberghe, R.; Ahmed, S.; Bak, T.H.; et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.X.; Shakespeare, T.J.; Cash, D.; Henley, S.M.; Nicholas, J.M.; Ridgway, G.R.; Golden, H.L.; Warrington, E.K.; Carton, A.M.; Kaski, D.; et al. Prominent effects and neural correlates of visual crowding in a neurodegenerative disease population. Brain 2014, 137, 3284–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Barnes, J.; Ridgway, G.R.; Ryan, N.S.; Warrington, E.K.; Crutch, S.J.; Fox, N.C. Global gray matter changes in posterior cortical atrophy: A serial imaging study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012, 8, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; Gordon, B.A.; Jackson, K.; Christensen, J.J.; Rosana Ponisio, M.; Su, Y.; Ances, B.M.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Morris, J.C. Tau-PET Binding Distinguishes Patients with Early-Stage Posterior Cortical Atrophy from Amnestic Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2017, 31, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoshima, S.; Cross, D.; Thientunyakit, T.; Foster, N.L.; Drzezga, A. (18)F-FDG PET Imaging in Neurodegenerative Dementing Disorders: Insights into Subtype Classification, Emerging Disease Categories, and Mixed Dementia with Copathologies. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 2S–12S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.A.; Martin, P.R.; Graff-Radford, J.; Sintini, I.; Machulda, M.M.; Duffy, J.R.; Gunter, J.L.; Botha, H.; Jones, D.T.; Lowe, V.J.; et al. Altered within- and between-network functional connectivity in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Commun. 2023, 5, fcad184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaccio, R.; Agosta, F.; Rascovsky, K.; Karydas, A.; Bonasera, S.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Miller, B.L.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L. Clinical syndromes associated with posterior atrophy: Early age at onset AD spectrum. Neurology 2009, 73, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMonagle, P.; Deering, F.; Berliner, Y.; Kertesz, A. The cognitive profile of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology 2006, 66, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutch, S.J.; Lehmann, M.; Warren, J.D.; Rohrer, J.D. The language profile of posterior cortical atrophy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013, 84, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnin, E.; Sylvestre, G.; Lenoir, F.; Dariel, E.; Bonnet, L.; Chopard, G.; Tio, G.; Hidalgo, J.; Ferreira, S.; Mertz, C.; et al. Logopenic syndrome in posterior cortical atrophy. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.B.; Lucente, D.; Larvie, M.; Cobos, M.I.; Frosch, M.; Dickerson, B.C. A 63-Year-Old Man with Progressive Visual Symptoms. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzloff, K.A.; Duffy, J.R.; Strand, E.A.; Machulda, M.M.; Schwarz, C.G.; Senjem, M.L.; Jack, C.R.; Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L. Phonological Errors in Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2021, 50, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.A.; Graff-Radford, J.; Machulda, M.M.; Carlos, A.F.; Schwarz, C.G.; Senjem, M.L.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Lowe, V.J.; Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L. Atypical Alzheimer’s disease: New insights into an overlapping spectrum between the language and visual variants. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 3571–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.A.; Goodrich, A.W.; Graff-Radford, J.; Machulda, M.M.; Sintini, I.; Carlos, A.F.; Robinson, C.G.; Reid, R.I.; Lowe, V.J.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; et al. Altered structural and functional connectivity in Posterior Cortical Atrophy and Dementia with Lewy bodies. NeuroImage 2024, 290, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putcha, D.; Eustace, A.; Carvalho, N.; Wong, B.; Quimby, M.; Dickerson, B.C. Auditory naming is impaired in posterior cortical atrophy and early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1342928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Caswell, J.; Butler, C.R.; Bose, A. Secondary language impairment in posterior cortical atrophy: Insights from sentence repetition. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1359186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, R.P.; Graff-Radford, J.; Machulda, M.M.; Schwarz, C.G.; Lowe, V.J.; Jones, D.T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L.; Botha, H. Baseline multimodal imaging to predict longitudinal clinical decline in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 2024, 180, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipkin, B.; Tuckute, G.; Affourtit, J.; Small, H.; Mineroff, Z.; Kean, H.; Jouravlev, O.; Rakocevic, L.; Pritchett, B.; Siegelman, M.; et al. Probabilistic atlas for the language network based on precision fMRI data from >800 individuals. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorenko, E.; Ivanova, A.A.; Regev, T.I. The language network as a natural kind within the broader landscape of the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overath, T.; McDermott, J.H.; Zarate, J.M.; Poeppel, D. The cortical analysis of speech-specific temporal structure revealed by responses to sound quilts. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hiersche, K.J.; Saygin, Z.M. Demystifying visual word form area visual and nonvisual response properties with precision fMRI. iScience 2024, 27, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, F.H. Neural Control of Speech; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Silbert, L.J.; Honey, C.J.; Simony, E.; Poeppel, D.; Hasson, U. Coupled neural systems underlie the production and comprehension of naturalistic narrative speech. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4687–E4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagharchakian, L.; Dehaene-Lambertz, G.; Pallier, C.; Dehaene, S. A temporal bottleneck in the language comprehension network. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 9089–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Small, H.; Kean, H.; Takahashi, A.; Zekelman, L.; Kleinman, D.; Ryan, E.; Nieto-Castanon, A.; Ferreira, V.; Fedorenko, E. Precision fMRI reveals that the language-selective network supports both phrase-structure building and lexical access during language production. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 4384–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, M. Neural representation of sensorimotor features in language-motor areas during auditory and visual perception. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berent, I.; Brem, A.K.; Zhao, X.; Seligson, E.; Pan, H.; Epstein, J.; Stern, E.; Galaburda, A.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Role of the motor system in language knowledge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, X. The dynamic and task-dependent representational transformation between the motor and sensory systems during speech production. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Gong, L.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, X. Seeing Chinese characters in action: An fMRI study of the perception of writing sequences. Brain Lang. 2011, 119, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J. The multiple-demand (MD) system of the primate brain: Mental programs for intelligent behaviour. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R.; Kanwisher, N. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. NeuroImage 2003, 19, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, R.L.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R.; Schacter, D.L. The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kas, A.; de Souza, L.C.; Samri, D.; Bartolomeo, P.; Lacomblez, L.; Kalafat, M.; Migliaccio, R.; Thiebaut de Schotten, M.; Cohen, L.; Dubois, B.; et al. Neural correlates of cognitive impairment in posterior cortical atrophy. Brain 2011, 134, 1464–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadhouse, K.M.; Winks, N.J.; Summers, M.J. Fronto-temporal functional disconnection precedes hippocampal atrophy in clinically confirmed multi-domain amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1458–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Wiste, H.J.; Therneau, T.M.; Weigand, S.D.; Knopman, D.S.; Mielke, M.M.; Lowe, V.J.; Vemuri, P.; Machulda, M.M.; Schwarz, C.G.; et al. Associations of Amyloid, Tau, and Neurodegeneration Biomarker Profiles with Rates of Memory Decline Among Individuals Without Dementia. JAMA 2019, 321, 2316–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bedirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, E.; James, M. The Visual Object and Space Perception Battery 1991; Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St Edmunds, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D.; Patterson, K. The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test: A Test of Semantic Access from Words and Picture; Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St Edmunds, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass, H.; Barresi, B. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination: Short Form Record Booklet 2000; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lansing, A.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Cullum, C.M.; Randolph, C. An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1999, 14, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffel, L.; Duffy, J.R.; Strand, E.A.; Josephs, K.A. Word Fluency Test Performance in Primary Progressive Aphasia and Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2021, 30, 2635–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.A.; Arani, A.; Graff-Radford, J.; Senjem, M.L.; Martin, P.R.; Machulda, M.M.; Schwarz, C.G.; Shu, Y.; Cogswell, P.M.; Knopman, D.S.; et al. Distinct brain iron profiles associated with logopenic progressive aphasia and posterior cortical atrophy. NeuroImage Clin. 2022, 36, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, R.; Ali, F.; Botha, H.; Lowe, V.J.; Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L. Direct comparison between (18)F-Flortaucipir tau PET and quantitative susceptibility mapping in progressive supranuclear palsy. NeuroImage 2024, 286, 120509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.D.; Schlaggar, B.L.; Petersen, S.E. Recent progress and outstanding issues in motion correction in resting state fMRI. NeuroImage 2015, 105, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M.J.; Mock, B.J.; Sorenson, J.A. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. NeuroImage 1998, 7, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diachek, E.; Blank, I.; Siegelman, M.; Affourtit, J.; Fedorenko, E. The Domain-General Multiple Demand (MD) Network Does Not Support Core Aspects of Language Comprehension: A Large-Scale fMRI Investigation. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 4536–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Dore, R.; Cho, M.; Golinkoff, R.; Amendum, S. Theory of mind, mental state talk, and discourse comprehension: Theory of mind process is more important for narrative comprehension than for informational text comprehension. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 209, 105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; MacPherson, S.E.; Hoffman, P. Balancing act: A neural trade-off between coherence and creativity in spontaneous speech. Cortex 2025, 190, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCandliss, B.D.; Cohen, L.; Dehaene, S. The visual word form area: Expertise for reading in the fusiform gyrus. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, S.; Maurer, U.; Kronbichler, M.; Schurz, M.; Richlan, F.; Blau, V.; Reithler, J.; van der Mark, S.; Schulz, E.; Bucher, K.; et al. Visual word form processing deficits driven by severity of reading impairments in children with developmental dyslexia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshorn, E.A.; Li, Y.; Ward, M.J.; Richardson, R.M.; Fiez, J.A.; Ghuman, A.S. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8162–8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saygin, Z.M.; Osher, D.E.; Norton, E.S.; Youssoufian, D.A.; Beach, S.D.; Feather, J.; Gaab, N.; Gabrieli, J.D.; Kanwisher, N. Connectivity precedes function in the development of the visual word form area. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, R.V.; Taoka, M.; Suzuki, H.; Iriki, A. Secondary somatosensory cortex of primates: Beyond body maps, toward conscious self-in-the-world maps. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvermuller, F.; Huss, M.; Kherif, F.; Moscoso del Prado Martin, F.; Hauk, O.; Shtyrov, Y. Motor cortex maps articulatory features of speech sounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7865–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinker, A.; Korzeniewska, A.; Shestyuk, A.Y.; Franaszczuk, P.J.; Dronkers, N.F.; Knight, R.T.; Crone, N.E. Redefining the role of Broca’s area in speech. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2871–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.M.; Chauvin, R.J.; Van, A.N.; Rajesh, A.; Nielsen, A.; Newbold, D.J.; Lynch, C.J.; Seider, N.A.; Krimmel, S.R.; Scheidter, K.M.; et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature 2023, 617, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmurget, M.; Sirigu, A. Revealing humans’ sensorimotor functions with electrical cortical stimulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.; Todt, I.; Knutzen, A.; Gless, C.A.; Granert, O.; Wolff, S.; Marquardt, C.; Becktepe, J.S.; Peters, S.; Witt, K.; et al. Neural Correlates of Executed Compared to Imagined Writing and Drawing Movements: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 829576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorden, C. MRIcroGL: Voxel-based visualization for neuroimaging. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1613–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, R.M.; Mohr, J.P. Revisiting the contributions of Paul Broca to the study of aphasia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2011, 21, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupe, L.A.; Varma, D.D.; Gomez, Y.; Race, D.; Leigh, R.; Hillis, A.E.; Gottesman, R.F. Chronic apraxia of speech and Broca’s area. Stroke 2013, 44, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, P.D. From Sound to Meaning: Navigating Wernicke’s Area in Language Processing. Cureus 2024, 16, e69833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutch, S.J.; Lehmann, M.; Schott, J.M.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Rossor, M.N.; Fox, N.C. Posterior cortical atrophy. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonakdarpour, B.; Hurley, R.S.; Wang, A.R.; Fereira, H.R.; Basu, A.; Chatrathi, A.; Guillaume, K.; Rogalski, E.J.; Mesulam, M.M. Perturbations of language network connectivity in primary progressive aphasia. Cortex 2019, 121, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh-Reilly, N.; Botha, H.; Duffy, J.R.; Clark, H.M.; Utianski, R.L.; Machulda, M.M.; Graff-Radford, J.; Schwarz, C.G.; Petersen, R.C.; Lowe, V.J.; et al. Speech-language within and between network disruptions in primary progressive aphasia variants. NeuroImage Clin. 2024, 43, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, R.; Agosta, F.; Toba, M.N.; Samri, D.; Corlier, F.; de Souza, L.C.; Chupin, M.; Sharman, M.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Dubois, B.; et al. Brain networks in posterior cortical atrophy: A single case tractography study and literature review. Cortex 2012, 48, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley, R.A.; Botha, H.; Graff-Radford, J.; Whitwell, J.; Boeve, B.F.; Machulda, M.M.; Fields, J.A.; Drubach, D.A.; Savica, R.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. Posterior cortical atrophy phenotypic heterogeneity revealed by decoding (18)F-FDG-PET. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Mandic-Stojmenovic, G.; Canu, E.; Stojkovic, T.; Imperiale, F.; Caso, F.; Stefanova, E.; Copetti, M.; Kostic, V.S.; Filippi, M. Functional and structural brain networks in posterior cortical atrophy: A two-centre multiparametric MRI study. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 19, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daho, M.; Monzani, D. The multifaceted nature of inner speech: Phenomenology, neural correlates, and implications for aphasia and psychopathology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2025, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic, S.; Mandelli, M.L.; Welch, A.; Jordan, K.; Shwe, W.; Neuhaus, J.; Miller, Z.; Hubbard, H.I.; Henry, M.; Miller, B.L.; et al. Neurocognitive basis of repetition deficits in primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2019, 194, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourovitch, M.L.; Kirkby, B.S.; Goldberg, T.E.; Weinberger, D.R.; Gold, J.M.; Esposito, G.; Van Horn, J.D.; Berman, K.F. A comparison of rCBF patterns during letter and semantic fluency. Neuropsychology 2000, 14, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams Roberson, S.; Shah, P.; Piai, V.; Gatens, H.; Krieger, A.M.; Lucas, T.H., 2nd; Litt, B. Electrocorticography reveals spatiotemporal neuronal activation patterns of verbal fluency in patients with epilepsy. Neuropsychologia 2020, 141, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quental, N.B.M.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Bueno, O.F.A. Visuospatial Function in Early Alzheimer’s Disease—The Use of the Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP) Battery. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockbridge, M.D.; Tippett, D.C.; Breining, B.L.; Vitti, E.; Hillis, A.E. Task performance to discriminate among variants of primary progressive aphasia. Cortex 2021, 145, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, L.A.; Buchanan, J.A. Psychometric properties of the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 31, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeare, K.B.; Cutler, L.; An, K.Y.; Razvi, P.; Holcomb, M.; Erdodi, L.A. BNT 15: Revised performance validity cutoffs and proposed clinical classification ranges. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 35, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attridge, J.; Zimmerman, D.; Rolin, S.; Davis, J. Comparing Boston Naming Test short forms in a rehabilitation sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsch, A.U.; Bondi, M.W.; Butters, N.; Salmon, D.P.; Katzman, R.; Thal, L.J. Comparisons of verbal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch. Neurol. 1992, 49, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombaugh, T.N.; Kozak, J.; Rees, L. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1999, 14, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- St Hilaire, A.; Hudon, C.; Vallet, G.T.; Bherer, L.; Lussier, M.; Macoir, J. Normative data for phonemic and semantic verbal fluency test in the adult French Quebec population and validation study in Alzheimer’s disease and depression. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 30, 1126–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCA (n = 37) | CU (n = 39) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 22 (60%) | 27 (69%) | 0.47 |

| Education, yr | 16 (13, 18) | 18 (16, 18) | 0.07 |

| Age at onset, yr | 58.2 (54.9, 61.1) | - | - |

| Age at scan, yr | 62.7 (59.5, 66.2) | 61.6 (56.4, 66) | 0.17 |

| Time from onset to scan, yr | 4.28 (3.07, 5.86) | - | - |

| MoCA (30) | 17 (10, 20) | 27 (26, 28) | <0.0001 |

| Simultanagnosia (20) | 7 (3, 11) | - | - |

| VOSP Cube Analysis (10) | 1 (0, 3) | - | - |

| VOSP Incomplete Letters (20) | 11 (6, 15) | - | - |

| BNT-SF (15) | 12 (9.8, 14) | - | - |

| BDAE repetition (10) | 9 (8, 10) | - | - |

| Letter fluency | 32 (23, 38.5) | - | - |

| Animal fluency | 13.5 (8.5, 15) | - | - |

| PPT word-word (52) | 50 (49, 51) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh-Reilly, N.; Satoh, R.; Watanabe, H.; Graff-Radford, J.; Machulda, M.M.; Lowe, V.J.; Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L. Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Altered Language Processing System Connectivity and Its Implications on Language Comprehension and Production. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121287

Singh-Reilly N, Satoh R, Watanabe H, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Lowe VJ, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL. Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Altered Language Processing System Connectivity and Its Implications on Language Comprehension and Production. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121287

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh-Reilly, Neha, Ryota Satoh, Hiroyuki Watanabe, Jonathan Graff-Radford, Mary M. Machulda, Val J. Lowe, Keith A. Josephs, and Jennifer L. Whitwell. 2025. "Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Altered Language Processing System Connectivity and Its Implications on Language Comprehension and Production" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121287

APA StyleSingh-Reilly, N., Satoh, R., Watanabe, H., Graff-Radford, J., Machulda, M. M., Lowe, V. J., Josephs, K. A., & Whitwell, J. L. (2025). Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Altered Language Processing System Connectivity and Its Implications on Language Comprehension and Production. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121287