A Review of Therapeutic Approaches for Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

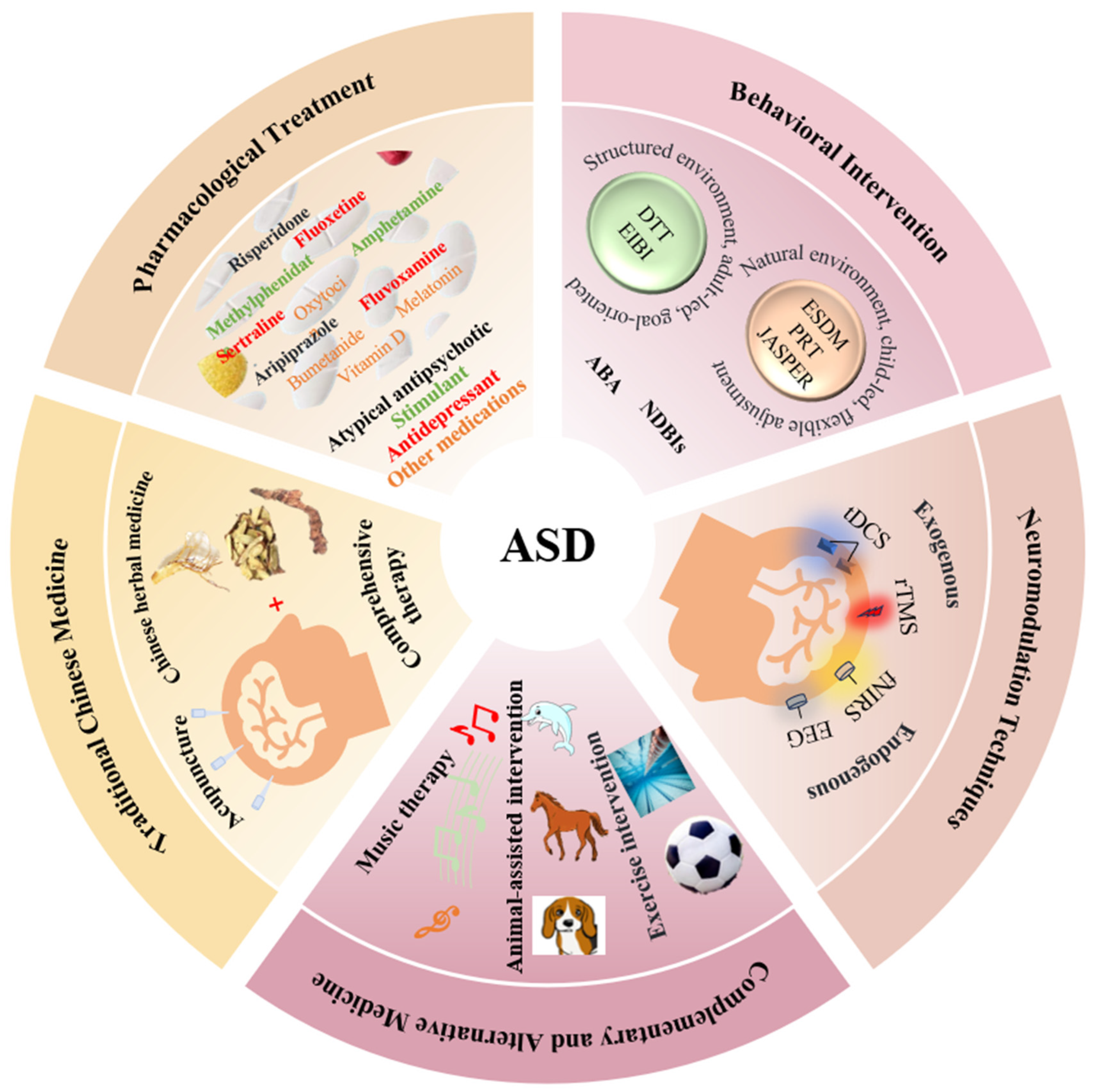

1. Introduction

2. Pharmacological Treatment

2.1. Atypical Antipsychotic

2.2. Stimulant

2.3. Antidepressant

2.4. Neuroendocrinological Therapies

2.5. Advantages, Limitations, and Development Directions

3. Behavioral Intervention

3.1. Applied Behavior Analysis

3.2. Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions

3.3. Advantages, Limitations, and Development Directions

4. Traditional Chinese Medicine

4.1. Acupuncture

4.2. Chinese Herbal Medicine

4.3. Comprehensive Therapy

4.4. Advantages, Limitations, and Development Directions

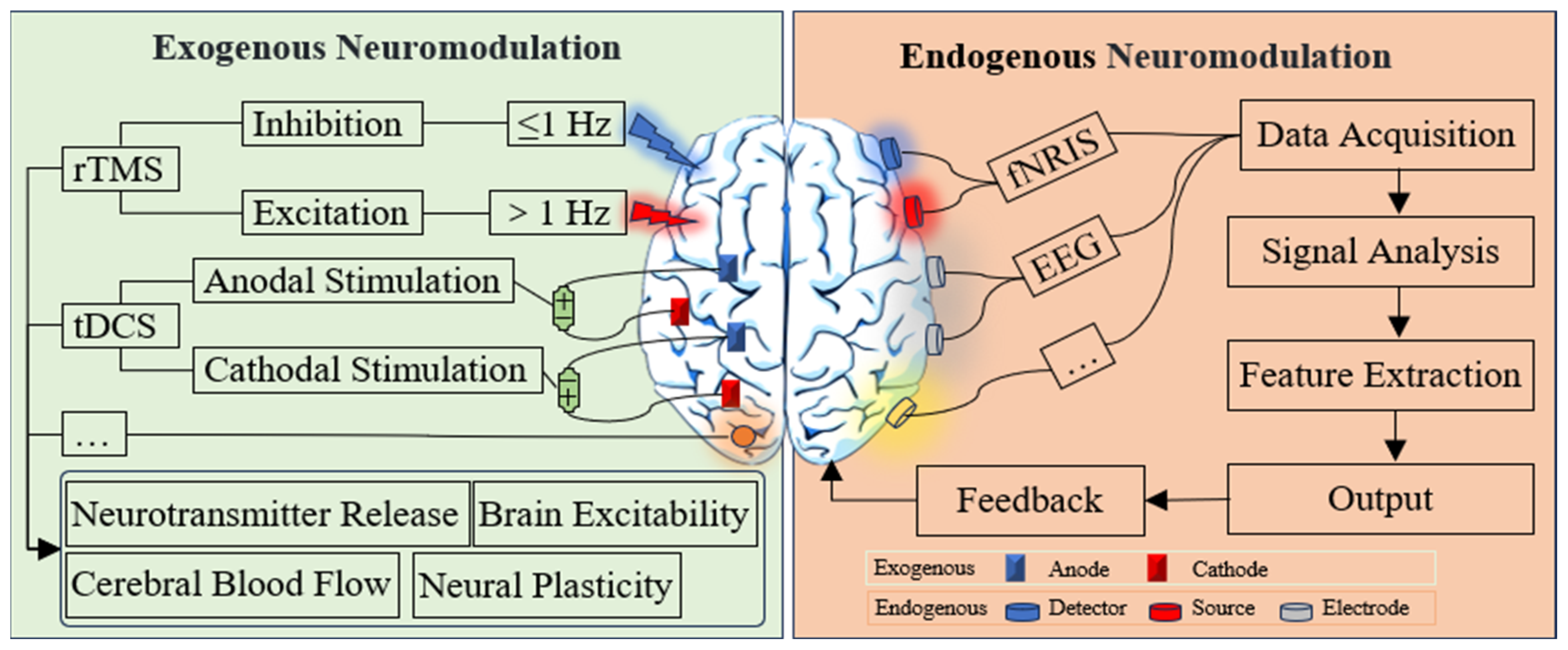

5. Neuromodulation Technique

5.1. Exogenous Neuromodulation Technology

5.2. Endogenous Neuromodulation Technology

5.3. Advantages, Limitations, and Development Directions

6. Complementary and Alternative Medicine

6.1. Music Therapy

6.2. Animal-Assisted Intervention

6.3. Exercise Intervention

6.4. Advantages, Limitations, and Development Directions

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, J.V.; Howard, M.; Menezes, M.; Burroughs, C.; Pappagianopoulos, J.; Sastri, V.; Brunt, S.; Miller, R.; Parenchuk, A.; Kuhn, J.; et al. Building capacity: A systematic review of training in the diagnosis of autism for community-based clinicians. Autism Res. 2025, 18, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlattani, T.; D’Amelio, C.; Cavatassi, A.; Luca, D.D.; Stefano, R.D.; Berardo, A.D.; Mantenuto, S.; Minutillo, F.; Leonardi, V.; Renzi, G.; et al. Autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric comorbidities: A narrative review. J. Psychopathol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, B.; Shivani, A. A new approach to hypobaric hypoxia induced cognitive impairment. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2012, 136, 365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Alnemary, F.M.; Aldhalaan, H.M.; Simon-Cereijido, G.; Alnemary, F.M. Services for children with autism in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Autism 2016, 21, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aishworiya, R.; Valica, T.; Hagerman, R.; Restrepo, B. An update on psychopharmacological treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreibman, L.; Dawson, G.; Stahmer, A.C.; Landa, R.; Rogers, S.J.; McGee, G.G.; Kasari, C.; Ingersoll, B.; Kaiser, A.P.; Bruinsma, Y.; et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2411–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.W.; Zhao, Z.M.; Han, Y.J.; Tai, X.T. Research progress in traditional Chinese medicine treatment of autistic spectrum disorders. J. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 38, 647–650. [Google Scholar]

- Hodaj, H.; Payen, J.F.; Mick, G.; Vercueil, L.; Hodaj, E.; Dumolard, A.; Noelle, B.; Delon-Martin, C.; Lefaucheur, J.P. Long-term prophylactic efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation in chronic migraine. A randomised, patient-assessor blinded, sham-controlled trial. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, R.; Ros, T.; Stoeckel, L.; Haller, S.; Scharnowski, F.; Lewis-Peacock, J.; Weiskopf, N.; Blefari, M.L.; Rana, M.; Oblak, E.; et al. Closed-loop brain training: The science of neurofeedback. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, S.; Palffy, A.; Popescu, R. 6.12 Pharmacological Treatments for the Core Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, S161–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.; Lee, J. Psychopharmacotherapy for children with autism spectrum disorder can improve their adaptive functioning. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 28, i256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinchii, D.; Dremencov, E. Mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs in mood disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguas, D.; Correll, C.U.; Merchan-Naranjo, J.; Rapado-Castro, M.; Parellada, M.; Moreno, C.; Arango, C. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders: Comprehensive review of prospective head-to-head and placebo-controlled comparisons. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Hong, J.S.; Findling, R.L.; Ji, N.Y. An update on pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobski, K.; Hofer, J.; Hoffmann, F.; Bachmann, C. Use of psychotropic drugs in patients with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayouf, H.A.; Talo, H.; Biddappa, M.L.; Qasaymeh, M.; Qasem, S.; De Los Reyes, E. Pharmacological intervention in children with autism spectrum disorder with standard supportive therapies significantly improves core signs and symptoms: A single-center, retrospective case series. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2779–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.P.; Fan, J.; Bedard, A.C.; Clerkin, S.M.; Ivanov, I.; Tang, C.Y.; Halperin, J.M.; Newcorn, J.H. Common and unique therapeutic mechanisms of stimulant and nonstimulant treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.; Baler, R.D.; Volkow, N.D. Understanding the effects of stimulant medications on cognition in individuals with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A decade of progress. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Lai, M.C.; Beswick, A.; Gorman, D.A.; Anagnostou, E.; Szatmari, P.; Anderson, K.K.; Ameis, S.H. Practitioner review: Pharmacological treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, N.; Deckx, L.; van Driel, M.L. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD011144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, R.L. Editorial: What to do about rigid, repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E.; Soorya, L.; Chaplin, W.; Anagnostou, E.; Taylor, B.P.; Ferretti, C.J.; Wasserman, S.; Swanson, E.; Settipani, C. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for repetitive behaviors and global severity in adult autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argonis, R.A.; Pedapati, E.V.; Dominick, K.C.; Harris, K.; Lamy, M.; Fosdick, C.; Schmitt, L.; Shaffer, R.C.; Smith, E.; Will, M.; et al. Patterns in medication use for treatment of depression in autistic spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, 55, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, G. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline. In NeuroPsychopharmacotherapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchiuti, G.; Taillieu, A.; Tuerlinckx, E.; Prinsen, J.; Debbaut, E.; Steyaert, J.; Boets, B.; Alaerts, K. Oxytocin’s social and stress-regulatory effects in children with autism and intellectual disability: A protocol for a randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y. Oxytocin lipidation expanding therapeutics for long-term reversal of autistic behaviors in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 672, 125299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, L.; Guarnera, E.; Kolmar, H.; Becker, S. Allosteric antibodies: A novel paradigm in drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aran, A.; Harel, M.; Cassuto, H.; Polyansky, L.; Schnapp, A.; Wattad, N.; Shmueli, D.; Golan, D.; Castellanos, F.X. Cannabinoid treatment for autism: A proof-of-concept randomized trial. Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretzsch, C.M.; Voinescu, B.; Mendez, M.A.; Wichers, R.; Ajram, L.; Ivin, G.; Heasman, M.; Williams, S.; Murphy, D.G.; Daly, E.; et al. The effect of cannabidiol (CBD) on low-frequency activity and functional connectivity in the brain of adults with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolevzon, A.; Breen, M.S.; Siper, P.M.; Halpern, D.; Frank, Y.; Rieger, H.; Weismann, J.; Trelles, M.P.; Lerman, B.; Rapaport, R.; et al. Clinical trial of insulin-like growth factor-1 in Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Mol. Autism 2022, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, H.; Mikami, K.; Okada, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Ishizaki, Y.; Tomoda, A.; Ono, H.; Usuki, C.; Tadori, Y. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in Japan: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, J.T.; McGough, J.; Shah, B.; Cronin, P.; Hong, D.; Aman, M.G.; Arnold, L.E.; Lindsay, R.; Nash, P.; Hollway, J.; et al. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, R.N.; Owen, R.; Kamen, L.; Manos, G.; McQuade, R.D.; Carson, W.H.; Aman, M.G. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, P.; Mathew, N.M.; Lee, E.; Busaibe, Y.; Phagava, T.; Wang, E.; Bs, R.N.; Dua, S.S.; M, M.O. Management of dissociation in high-functioning autism adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2025, 7, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, N.; Franco, J.V.A.; Sguassero, Y.; Núñez, V.; Escobar Liquitay, C.M.; Rees, R.; Williams, K.; Rojas, V.; Rojas, F.; Pringsheim, T.; et al. Atypical antipsychotics for autism spectrum disorder: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, P.P.; Johnson, K.A.; Riesenberg, R.; Orejudos, A.; Riccobene, T.; Kalluri, H.V.; Malik, P.R.; Varughese, S.; Findling, R.L. Cariprazine in Pediatric Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a Pharmacokinetic, Safety and Tolerability Study. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 33, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, R.L.; Bozhdaraj, D.; Duffy, W.J.; Knutson, J.A.; Weinberg, M.S.; Rekeda, L.; Chen, C.; Smith, E.M.; Lucas, M.B. Cariprazine in the Treatment of Pediatric Patients With Irritability Associated With ASD: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 64, S331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljead, M.; Qashta, A.; Jalal, Z.; Jones, A.M. Review of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Epidemiology, Aetiology, Pathology, and Pharmacological Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, R.; Dharmapuri, S. Reconceptualilzing agitation in autism as primary affective dysregulation: Case report and literature review of use of quetiapine in a patient with Treacher–Collins syndrome and autism. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 41, S434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tural Hesapcioglu, S.; Ceylan, M.F.; Kasak, M.; Sen, C.P. Olanzapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole use in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 72, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miuli, A.; Marrangone, C.; Di Marco, O.; Pasino, A.; Stigliano, G.; Mosca, A.; Pettorruso, M.; Schifano, F.; Martinotti, G. Could cariprazine be a possible choice for high functioning autism? A case report. Future Pharmacol. 2023, 3, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Childress, A.; Martinko, K.; Chen, D.; Larsen, K.G.; Shah, A.; Sheridan, P.; Hefting, N.; Knutson, J. Safety and Efficacy of Brexpiprazole in the Treatment of Irritability Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An 8-Week, Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial and 26-Week Open-Label Extension in Children and Adolescents. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 35, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politte, L.C.; McDougle, C.J. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, W.A.; Chung, C.P.; Murray, K.T.; Hall, K.; Stein, C.M. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khachadourian, V.; Mahjani, B.; Sandin, S.; Kolevzon, A.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Reichenberg, A.; Janecka, M. Comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder and their etiologies. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Yang, C.-J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Y. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2021, 83, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, O.D.; Rogdaki, M.; Findon, J.L.; Wichers, R.H.; Charman, T.; King, B.H.; Loth, E.; McAlonan, G.M.; McCracken, J.T.; Parr, J.R.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder: Consensus guidelines on assessment, treatment and research from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjappa, M.S.; Voyiaziakis, E.; Pradhan, B.; Mannekote Thippaiah, S. Use of selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), comorbid psychiatric disorders and ASD-associated symptoms: A clinical review. CNS Spectr. 2022, 27, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingard, R.J.; Zimnitzky, B.; DeMaso, D.R.; Bauman, M.L.; Bucci, J.P. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1997, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddihough, D.S.; Marraffa, C.; Mouti, A.; O’Sullivan, M.; Lee, K.J.; Orsini, F.; Hazell, P.; Granich, J.; Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Wray, J.; et al. Effect of Fluoxetine on Obsessive-Compulsive Behaviors in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougle, C.J.; Naylor, S.T.; Cohen, D.J.; Volkmar, F.R.; Heninger, G.R.; Price, L.H. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T.W. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and heart defects: Potential mechanisms for the observed associations. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 32, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manter, M.A.; Birtwell, K.B.; Bath, J.; Friedman, N.D.B.; Keary, C.J.; Neumeyer, A.M.; Palumbo, M.L.; Thom, R.P.; Stonestreet, E.; Brooks, H.; et al. Pharmacological treatment in autism: A proposal for guidelines on common co-occurring psychiatric symptoms. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, G.G.; Gerber, F.; Darbellay, B.; Kosel, M.M.; Deriaz, N.; Chabert, J.; Fathi, M.; Bertschy, G.; Ferrero, F.; Carminati, F. Using venlafaxine to treat behavioral disorders in patients with autism spectrum disorder. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 65, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonnier, E.; Villeneuve, N.; Sonie, S.; Serret, S.; Rosier, A.; Roue, M.; Brosset, P.; Viellard, M.; Bernoux, D.; Rondeau, S.; et al. Effects of bumetanide on neurobehavioral function in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, X.; He, H.; Ji, Y.; Wang, K.; Du, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; et al. Improved symptoms following bumetanide treatment in children aged 3-6 years with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjikhani, N.; Zurcher, N.R.; Rogier, O.; Ruest, T.; Hippolyte, L.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Lemonnier, E. Improving emotional face perception in autism with diuretic bumetanide: A proof-of-concept behavioral and functional brain imaging pilot study. Autism 2015, 19, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignell, A.; Marraffa, C.; Williams, K.; May, T. Memantine for autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 8, CD013845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nikvarz, N.; Alaghband-Rad, J.; Tehrani-Doost, M.; Alimadadi, A.; Ghaeli, P. Comparing efficacy and side effects of memantine vs. risperidone in the treatment of autistic disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry 2017, 50, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry-Kravis, E.; Hagerman, R.; Visootsak, J.; Budimirovic, D.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Cherubini, M.; Zarevics, P.; Walton-Bowen, K.; Wang, P.; Bear, M.F.; et al. Arbaclofen in fragile X syndrome: Results of phase 3 trials. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2017, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Cook, E.H.; King, B.H.; Zarevics, P.; Cherubini, M.; Walton-Bowen, K.; Bear, M.F.; Wang, P.P.; Carpenter, R.L. Arbaclofen in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized, controlled, phase 2 trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 1390–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Wang, B.; Shan, L.; Xu, Z.; Staal, W.G.; Du, L. Core symptoms of autism improved after vitamin D supplementation. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e196–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, K.; Abdel-Rahman, A.A.; Elserogy, Y.M.; Al-Atram, A.A.; Cannell, J.J.; Bjorklund, G.; Abdel-Reheim, M.K.; Othman, H.A.; El-Houfey, A.A.; Abd El-Aziz, N.H.; et al. Vitamin D status in autism spectrum disorders and the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in autistic children. Nutr. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gringras, P.; Nir, T.; Breddy, J.; Frydman-Marom, A.; Findling, R.L. Efficacy and safety of pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 948–957.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malow, B.A.; Findling, R.L.; Schroder, C.M.; Maras, A.; Breddy, J.; Nir, T.; Zisapel, N.; Gringras, P. Sleep, growth, and puberty after 2 years of prolonged-release melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 252–261.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roane, H.S.; Fisher, W.W.; Carr, J.E. Applied behavior analysis as treatment for autism spectrum disorder. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, J.B.; Cihon, J.H.; Ferguson, J.L.; Milne, C.M.; Leaf, R.; McEachin, J. Advances in our understanding of behavioral intervention: 1980 to 2020 for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 4395–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnova, G.V.; Ivanova, O.; Proskurnina, E.V. Effects of EEG examination and ABA-therapy on resting-state EEG in children with low-functioning autism. AIMS Neurosci. 2020, 7, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrygianni, M.K.; Gena, A.; Katoudi, S.; Galanis, P. The effectiveness of applied behavior analytic interventions for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A meta-analytic study. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 51, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitimoghaddam, M.; Chichkine, N.; McArthur, L.; Sangha, S.S.; Symington, V. Applied behavior analysis in children and youth with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 45, 521–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepri, A. Psychoeducational and behavioral interventions in autism spectrum disorder: Is the ABA method really the most effective? Psychiatr. Danub. 2024, 36, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sulu, M.D.; Aydin, O.; Martella, R.C.; Erden, E.; Ozen, Z. A meta-analysis of applied behavior analysis-based interventions for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Turkey. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes, T.; Buhlmann, U.; Holling, H.D.; Mollmann, A. Comprehensive ABA-based interventions in the treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder—A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Reilly, M.; Reichow, B. Overview of meta-analyses on naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, 55, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, J.; Yoder, P.; Crandall, M.; Millan, M.E.; Ardel, C.M.; Gengoux, G.W.; Hardan, A.Y. Effects of pivotal response treatment on reciprocal vocal contingency in a randomized controlled trial of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2020, 24, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington, H.; Reynolds, J.E.; Macaskill, E.; Curtis, S.; Taylor, L.J.; Whitehouse, A.J. The effects of JASPER intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism 2021, 25, 2370–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, A.; Munson, J.; Rogers, S.J.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G. Long-term outcomes of early intervention in 6-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, G.; Walton, K.M. Meta-analysis of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019, 23, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.; Rogers, S.; Munson, J.; Smith, M.; Winter, J.; Greenson, J.; Donaldson, A.; Varley, J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e17–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardan, A.Y.; Gengoux, G.W.; Berquist, K.L.; Libove, R.A.; Ardel, C.M.; Phillips, J.; Frazier, T.W.; Minjarez, M.B. A randomized controlled trial of pivotal response treatment group for parents of children with autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasari, C.; Gulsrud, A.; Paparella, T.; Hellemann, G.; Berry, K. Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, C.H.; Ip, C.L.; Chau, Y.Y. The therapeutic effect of scalp acupuncture on natal autism and regressive autism. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.L.; Guo, Y.X.; Ma, Y.F.; Luo, S.J.; Liu, Q.S.; Jin, X.; Chen, Y.N. Review of TCM treatment in autism spectrum disorders. Guid. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2020, 26, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.R.; Lv, X.L.; Hao, J.S.; Yin, H.N.; Li, Z.X.; Zeng, X.X. Research overview of autism treated by scalp acupuncture. China J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharm. 2017, 32, 5499–5501. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, R.C.; Wu, Z.F.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, X.J.; Jin, R. Observation on clinical therapeutic effect of JIN’s 3-needling therapy on severe autism. Chin. Acupunct. Moxibustion 2009, 29, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V.C.; Chen, W.-X.; Liu, W.-L. Randomized controlled trial of electro-acupuncture for autism spectrum disorder. Altern. Med. Rev. 2010, 15, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q.F.; Wang, X.F.; Li, Z.H.; Li, W.J.; Jia, R.; Yue, Z.X.; Zhu, Z.J.; Ma, B.X. Study on the Therapeutic Effect of Yu-Mu-Tiao-Shen Acupuncture on Rats with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2025, 21, 2195–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Huang, L.S.; Liu, G.H.; Kang, J.; Qian, Q.F.; Wang, J.R.; Wang, R.; Zheng, L.Z.; Wang, H.J.; Ou, P. Acupuncture Ameliorated Behavioral Abnormalities in the Autism Rat Model via Pathways for Hippocampal Serotonin. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Xiaofang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Huang, X.; Kang, J.; Ou, P.; Huang, L. Chinese acupuncture: A potential treatment for autism rat model via improving synaptic function. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Jia, M.X.; Zhang, J.S.; Xu, X.J.; Shou, X.J.; Zhang, X.T.; Li, L.; Li, N.; Han, S.P.; Han, J.S. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in children with autism and its impact on plasma levels of arginine-vasopressin and oxytocin: A prospective single-blinded controlled study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Jia, S.W.; Hu, S.; Sun, W. Evaluating the effectiveness of electro-acupuncture as a treatment for childhood autism using single photon emission computed tomography. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2014, 20, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.S.; Cheung, M.C.; Sze, S.L.; Leung, W.W. Seven-Star Needle Stimulation Improves Language and Social Interaction of Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2009, 37, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, M.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, S.H.; Yu, S.A.; Kim, K.; Lu, H.Y.; Chang, G.T.; Min, S.Y. Herbal medicine treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 8614680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Q.; Xu, J.J.; Wan, L.J.; Cai, J.L. Review of traditional Chinese medicine treatment of pediatric autism. J. Pediatr. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 10, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.Y.; Qu, X.J.; Wang, S.L.; Gao, H.; He, L. Clinical observation of Yangxin Kangbi decoction combined with intervention training in the treatment of autism in children with deficiency of heart and spleen. Henan Tradit. Chin. Med. 2019, 39, 898–900. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.B.; Zhang, Y.J.; Luo, G.Q.; Li, L. Clinical study of infantile massage combined with acupuncture for autism. New Chin. Med. 2017, 49, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.N.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, W.J. Acupuncture combined with medicine in the treatment of 48 cases autism of hyperactivity of heart-fire and liver-fire. Jilin J. Chin. Med. 2017, 37, 400–403. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.K.; Xie, X.S.; Li, X.; Zhu, Q.X. Clinical efficacy of Chaihu plus longgu muli decoction combined with acupuncture and massage in the treatment of children with autism. Intern. Med. 2022, 17, 606–609. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, L.; Casanova, M.F.; Sokhadze, E.M.; Li, X. Effects of 1Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on autism with intellectual disability: A pilot study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadoush, H.; Nazzal, M.; Almasri, N.A.; Khalil, H.; Alafeef, M. Therapeutic effects of bilateral anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on prefrontal and motor cortical areas in children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatachaya, A.; Auvichayapat, N.; Patjanasoontorn, N.; Suphakunpinyo, C.; Ngernyam, N.; Aree-Uea, B.; Keeratitanont, K.; Auvichayapat, P. Effect of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on autism: A randomized double-blind crossover trial. Behav. Neurol. 2014, 2014, 173073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, F.; Menghini, D.; Casula, L.; Amendola, A.; Mazzone, L.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S. Transcranial direct current stimulation treatment in an adolescent with autism and drug-resistant catatonia. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 1233–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouijzer, M.E.J.; de Moor, J.M.H.; Gerrits, B.J.L.; Congedo, M.; van Schie, H.T. Neurofeedback improves executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouijzer, M.E.J.; de Moor, J.M.H.; Gerrits, B.J.L.; Buitelaar, J.K.; van Schie, H.T. Long-term effects of neurofeedback treatment in autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direito, B.; Mouga, S.; Sayal, A.; Simoes, M.; Quental, H.; Bernardino, I.; Playle, R.; McNamara, R.; Linden, D.E.; Oliveira, G.; et al. Training the social brain: Clinical and neural effects of an 8-week real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging neurofeedback Phase IIa Clinical Trial in Autism. Autism 2021, 25, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Cliffer, S.; Pradhan, A.H.; Lightbody, A.; Hall, S.S.; Reiss, A.L. Optical-imaging-based neurofeedback to enhance therapeutic intervention in adolescents with autism: Methodology and initial data. Neurophotonics 2017, 4, 011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGasse, A.B. Effects of a music therapy group intervention on enhancing social skills in children with autism. J. Music. Ther. 2014, 51, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.S. The influence of music on facial emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorder and neurotypical children. J. Music. Ther. 2017, 54, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, G.L.; Berning, M.; Costa, A.P.; Steffgen, G.; Melzer, A. Effects of emotional music on facial emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3256–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, A.; Ogden, J.; Winstone, N. The impact of a school-based musical contact intervention on prosocial attitudes, emotions and behaviours: A pilot trial with autistic and neurotypical children. Autism 2019, 23, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, G.E.; Kim, S.J. Dyadic drum playing and social skills: Implications for rhythm-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Music. Ther. 2018, 55, 340–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lense, M.D.; Beck, S.; Liu, C.; Pfeiffer, R.; Diaz, N.; Lynch, M.; Goodman, N.; Summers, A.; Fisher, M.H. Parents, peers, and musical play: Integrated parent-child music class program supports community participation and well-being for families of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 555717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.A.; McFerran, K.S.; Gold, C. Family-centred music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled study. Child. Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, S.; Colombo, B.; Clark, J.; Bonfanti, A.; Molteni, S.; Crippa, A.; Antonietti, A.; Molteni, M. Soundbeam imitation intervention: Training children with autism to imitate meaningless body gestures through music. Adv. Autism 2020, 6, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, L.; Pulcrano, S.; Perrone-Capano, C.; di Porzio, U.; Volpicelli, F. Music affects functional brain connectivity and is effective in the treatment of neurological disorders. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 33, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintin, E.-M. Music-Evoked Reward and Emotion: Relative Strengths and Response to Intervention of People With ASD. Front. Neural Circuits 2019, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.R.; Gonda, X.; Tarazi, F.I. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Classification, diagnosis and therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 190, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieleninik, L.; Geretsegger, M.; Mossler, K.; Assmus, J.; Thompson, G.; Gattino, G.; Elefant, C.; Gottfried, T.; Igliozzi, R.; Muratori, F.; et al. Effects of Improvisational Music Therapy vs Enhanced Standard Care on Symptom Severity Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: The TIME-A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriels, R.L.; Pan, Z.; Dechant, B.; Agnew, J.A.; Brim, N.; Mesibov, G. Randomized controlled trial of therapeutic horseback riding in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Espeso, N.; Martínez, E.R.; Sevilla, D.G.; Mas, L.A. Effects of dolphin-assisted therapy on the social and communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Anthrozoos 2021, 34, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Itzchak, E.; Zachor, D.A. Dog training intervention improves adaptive social communication skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder: A controlled crossover study. Autism 2021, 25, 1682–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieforth, L.O.; Schwichtenberg, A.J.; O’Haire, M.E. Animal-assisted interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature from 2016 to 2020. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 10, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Haire, M. Research on animal-assisted intervention and autism spectrum disorder, 2012–2015. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2017, 21, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetri, L.; Roccella, M. On the playing field to improve: A goal for autism. Medicina 2020, 56, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, E.; Crozier, M.; Lloyd, M. A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2016, 20, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, V.; Kilyk, A.; Srinivasan, S.M. Effects of physical activity and exercise-based interventions in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism 2024, 28, 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiong, X.; Chen, A. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, R.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, R.; Zhu, F.; Ruan, W.; Zhang, J. Comparative effectiveness of physical exercise interventions on sociability and communication in children and adolescents with autism: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, K.; Sivaratnam, C.; May, T.; Lindor, E.; McGillivray, J.; Rinehart, N. Efficacy of group-based organised physical activity participation for social outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3290–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Song, Z.; Deng, J.; Song, X. The impact of exercise intervention on social interaction in children with autism: A network meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1399642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Hu, F.; Zhu, Z. Benefits of exercise for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1462601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, R.; Wong, S.H.S.; Sum, R.K.W.; Wang, P.; Yang, B.; Sit, C.H.P. The effects of exercise interventions on executive functions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, R.A.; Robertson, M.C.; McCleery, J.P. Exercise interventions for autistic people: An integrative review of evidence from clinical trials. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2025, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Tse, A.C.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.X. The impact of the physical activity intervention on sleep in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2024, 74, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.; Paoletti, D.; De Stasio, S.; Berenguer, C. Sleep disturbances in autistic children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Autism 2025, 29, 1661–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuxi, R.; Shuqi, J.; Cong, L.; Shufan, L.; Yueyu, L. A systematic review of the effect of sandplay therapy on social communication deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1454710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Ou, P.; Huang, L.; Qian, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, H.G.; Hu, R. Effects of parent-child sandplay therapy for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder and their mothers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 71, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, D. Effects of image-sandplay therapy on the mental health and subjective well-being of children with autism. Iran. J. Public. Health 2021, 50, 2046–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, S.W.; Mullins, K.L.; Kumar, S. Art therapy for children and adolescents with autism: A systematic review. Int. J. Art. Ther. 2024, 30, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Ratcliff, K.; Hilton, C.; Fingerhut, P.; Li, C.Y. Art interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7605205030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, W.C.; Cheng, C.H.; Lam, W.Y.; Huang, Y.; Ng, K.C.; Tung, H.C.; Wong, W. A robot-based play-drama intervention may improve the joint attention and functional play behaviors of Chinese-speaking preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, B.F. The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis; BF Skinner Foundation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, C.J.; Cartigny, A.; Mellier, B.C.; Solanes, A.; Radua, J.; Delorme, R. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for Autism spectrum disorder: An umbrella review. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 3647–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; Lin, T.L.; Lin, H.Y.; Ho, S.Y.; Wong, C.C.; Wu, H.C. Short-term low-intensity Early Start Denver Model program implemented in regional hospitals in Northern Taiwan. Autism 2023, 27, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contaldo, A.; Colombi, C.; Pierotti, C.; Masoni, P.; Muratori, F. Outcomes and moderators of Early Start Denver Model intervention in young children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a mixed individual and group setting. Autism 2020, 24, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengoux, G.W.; Abrams, D.A.; Schuck, R.; Millan, M.E.; Libove, R.; Ardel, C.M.; Phillips, J.M.; Fox, M.; Frazier, T.W.; Hardan, A.Y. A pivotal response treatment package for children with autism spectrum disorder: An RCT. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berk-Smeekens, I.; de Korte, M.W.P.; van Dongen-Boomsma, M.; Oosterling, I.J.; den Boer, J.C.; Barakova, E.I.; Lourens, T.; Glennon, J.C.; Staal, W.G.; Buitelaar, J.K. Pivotal response treatment with and without robot-assistance for children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire, S.Y.; Chang, Y.C.; Shih, W.; Bracaglia, S.; Kodjoe, M.; Kasari, C. Hybrid implementation model of community-partnered early intervention for toddlers with autism: A randomized trial. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, G. Kasari et al.: The JASPER Model for Children with Autism: Promoting Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, Engagement, and Regulation. Guilford Publications. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 53, 2166–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, L.; Goodwin, C.D.; Rieder, A.; Matheis, M.; Damiano, D.L. Early intervention for very young children with or at high likelihood for autism spectrum disorder: An overview of reviews. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2022, 64, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, N.; Rojas, V.; Escobar Liquitay, C.M.; Perez, I.; Aguilera Johnson, F.; Amarales Osorio, C.; Irarrazaval, M.; Madrid, E.; Franco, J.V.A. Non-pharmacological interventions for autism spectrum disorder in children: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, S.N.; Dada, S.; Tönsing, K.; Samuels, A.; Owusu, P. Cultural considerations in caregiver-implemented naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: A scoping review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yuan, L.X. A brief analysis of the etiology, pathogenesis, and syndrome differentiation of pediatric autism in traditional Chinese medicine. Liaoning J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2007, 364, 1226–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L.; He, J.D. Exploration of the mental and behavioral abnormality characteristics of Autism in traditional Chinese medicine. J. Hunan Univ. Chin. Med. 2006, 26, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.R.; Xiong, Z.F.; He, A.N.; Cheng, Y.R.; Lei, Y.C.; Chen, H.B.; Li, J.W. Research status of acupuncture in treatment of autism. J. Hubei Univ. Chin. Med. 2020, 22, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; Kwon, C.Y.; Chang, G.T. Oriental herbal medicine for neurological disorders in children: An overview of systematic reviews. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1701–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, M.F. Study on the prescription patterns for treatment of autism spectrum disorders and action mechanism of its core herbal combinations. J. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2023, 40, 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.L.; Xu, D.; Diao, B.S. Research on current situation of TCM treatment of autism spectrum disorder. J. Med. Inf. 2020, 33, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Xing, J.J.; Li, J.; Zeng, B.Y.; Liang, F.R. History of acupuncture research. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2013, 111, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.Y.; Qu, L.F. Progress in traditional Chinese medicine research on pediatric autism spectrum disorder. Inn. Mong. J. Tradit. Chin. 2012, 31, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, J.-C.; Lu, Q.-Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.-Q. Research status and prospects of acupuncture for autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 942069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.L.; Zhao, M.Z.; Chen, H. Clinical research progress of treating autism in children in TCM. Clin. J. Chin. Med. 2023, 15, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi, A.; Zarafshan, H.; Vand, S.R.; Mohammadi, M.R. Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 527–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.X.; Wang, X.K.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Q.R.; Ma, S.Z.; Zang, Y.F.; Dong, W.Q. A systematic review of transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment for autism spectrum disorder. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Kang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Transcranial direct current stimulation modulates brain functional connectivity in autism. Neuroimage Clin. 2020, 28, 102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prillinger, K.; Amador de Lara, G.; Klobl, M.; Lanzenberger, R.; Plener, P.L.; Poustka, L.; Konicar, L.; Radev, S.T. Multisession tDCS combined with intrastimulation training improves emotion recognition in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, A.; Yildirim, A. Assessing the impact of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on social communication in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 161, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzer, J.; Papageorgiou, T.D.; Goebel, R.; Hendler, T. Neurofeedback: New territories and neurocognitive mechanisms of endogenous neuromodulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 379, 20230081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Bruzzese, D.; Ferrucci, R.; Priori, A.; Pascotto, A.; Galderisi, S.; Altamura, A.C.; Bravaccio, C. Transcranial direct current stimulation for hyperactivity and noncompliance in autistic disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 16, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Ferrucci, R.; Bruzzese, D.; Pascotto, A.; Priori, A.; Altamura, C.A.; Galderisi, S.; Bravaccio, C. Transcranial direct current stimulation for autistic disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, e5–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, S.; Lugo-Marin, J.; Setien-Ramos, I.; Gisbert-Gustemps, L.; Arteaga-Henriquez, G.; Diez-Villoria, E.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. Transcranial direct current stimulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 48, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esse Wilson, J.; Trumbo, M.C.; Wilson, J.K.; Tesche, C.D. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) for social cognition and social skills in adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, M.A.; Paknia, N.; Hosseinpour, A.H.; Yavari, F.; Vicario, C.M.; Nitsche, M.A.; Nejati, V. Contribution of the right temporoparietal junction and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to theory of mind in autism: A randomized, sham-controlled tDCS study. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1572–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.L. Using causal methods to map symptoms to brain circuits in neurodevelopment disorders: Moving from identifying correlates to developing treatments. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2022, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Conde, J.A.; Gonzalez-Bermudez, M.D.R.; Carretero-Rey, M.; Khan, Z.U. Brain stimulation: A therapeutic approach for the treatment of neurological disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vliet, R.; Jonker, Z.D.; Louwen, S.C.; Heuvelman, M.; de Vreede, L.; Ribbers, G.M.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Donchin, O.; Selles, R.W.; van der Geest, J.N.; et al. Cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation interacts with BDNF Val66Met in motor learning. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griff, J.R.; Langlie, J.; Bencie, N.B.; Cromar, Z.J.; Mittal, J.; Memis, I.; Wallace, S.; Marcillo, A.E.; Mittal, R.; Eshraghi, A.A. Recent advancements in noninvasive brain modulation for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, K.; Watanabe, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Kawato, M. Perceptual learning incepted by decoded fMRI neurofeedback without stimulus presentation. Science 2011, 334, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, R.M.; Moussa, N.D.; Salmawy, D.H.E.; Rizk, M.R.M.; Alim, O.A. A comparison between classical and new proposed feature selection methods for attention level recognition in disordered children. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 12785–12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; An, P.C.; Xiao, Y.G.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, H.; Katsuragawa, K.; Zhao, J. Eggly: Designing mobile augmented reality neurofeedback training games for children with autism spectrum disorder. Proc. Acm Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol.-Imwut 2023, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Habib, S.H. Neurofeedback recuperates cognitive functions in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 2891–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, E.V.; Sivanathan, A.; Lim, T.; Suttie, N.; Louchart, S.; Pillen, S.; Pineda, J.A. An effective neurofeedback intervention to improve social interactions in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 4084–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramot, M.; Kimmich, S.; Gonzalez-Castillo, J.; Roopchansingh, V.; Popal, H.; White, E.; Gotts, S.J.; Martin, A. Direct modulation of aberrant brain network connectivity through real-time NeuroFeedback. Elife 2017, 6, e28974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMarca, K.; Gevirtz, R.; Lincoln, A.J.; Pineda, J.A. Brain-computer interface training of mu EEG rhythms in intellectually impaired children with autism: A feasibility case series. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2023, 48, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMarca, K.; Gevirtz, R.; Lincoln, A.J.; Pineda, J.A. Facilitating neurofeedback in children with autism and intellectual impairments using TAGteach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2090–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, J.; Hoffmann, F.; Bachmann, C. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism 2016, 21, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretsegger, M.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Elefant, C.; Mossler, K.A.; Vitale, G.; Gold, C. Music therapy for autistic people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD004381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsirigoti, A.; Georgiadi, M. The efficacy of music therapy programs on the development of social communication in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Garcia, A.V.; Magnuson, J.; Morris, J.; Iarocci, G.; Doesburg, S.; Moreno, S. Music therapy in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 9, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.; Hu, A.; Long, Q.; Lee, Y. The effect of music therapy on language communication and social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1336421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Song, W.; Yang, M.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Effectiveness of music therapy in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 905113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, M.; Philip, J.L.; Priya, V.; Priyadarshini, S.; Ramasamy, M.; Jeevitha, G.C.; Mathkor, D.M.; Haque, S.; Dabaghzadeh, F.; Bhattacharya, P.; et al. Therapeutic use of music in neurological disorders: A concise narrative review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomi, J.S.; Molnar-Szakacs, I.; Uddin, L.Q. Insular function in autism: Update and future directions in neuroimaging and interventions. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, L.; Geretsegger, M.; Mayer-Ferbas, J. Effectiveness of music therapy for autism spectrum disorder, dementia, depression, insomnia and schizophrenia: Update of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Public. Health 2022, 32, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.; Chur-Hansen, A. An umbrella review of the evidence for equine-assisted interventions. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, J.H.; Blakemore, E.; Shafi, H.; Skotny, N.; Lloyd, D.M. Calm with horses? A systematic review of animal-assisted interventions for improving social functioning in children with autism. Autism 2022, 26, 1320–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornefeld, D.; Zellin, U.; Schmidt, P.; Fricke, O. The supporting role of dogs in the inpatient setting: A systematic review of the therapeutic effects of animal-assisted therapy with dogs for children and adolescents in an inpatient setting. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 34, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.; Falcomata, T.S.; Barnett, M. The collateral effects of antecedent exercise on stereotypy and other nonstereotypic behaviors exhibited by individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Behav. Anal. Pr. 2023, 16, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, G.; Jiang, N.; Chen, W.; Liu, L.; Hu, M.; Liao, B. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise interventions in autistic individuals. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 36, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, G.; Li, M.M. The effectiveness and sustained effects of exercise therapy to improve executive function in children and adolescents with autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; Yang, Y.; Wilson, M.; Chang, J.R.; Liu, C.; Sit, C.H.P. Comparative effectiveness of physical activity interventions on cognitive functions in children and adolescents with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, C.V.A.; Barros, L.; Lima, A.B.; Nunes, T.; Carvalho, H.M.; Gaspar, J.M. Neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorders: Exercise as a “pharmacological” tool. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 129, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment Methods | Classification | References | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological treatment | Atypical antipsychotic | [6,15,16,17,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Fast-acting, suitable for individuals with severe behavioral issues. | Limited improvement in core symptoms. Potential side effects. |

| Stimulant | [6,20,21,48] | |||

| Antidepressant | [23,24,25,50,51,52,53,54,55] | |||

| Other medications | [26,27,29,30,31,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] | |||

| Behavioral interventions | ABA | [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74] | Structured training programs that can be adjusted according to individual needs. The cornerstone of early intervention. | Long training periods. Significant individual variability in training outcomes. Effectiveness depends on the professional level of the therapists and the intensity of the intervention. |

| NDBIs | [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] | |||

| TCM | Acupuncture | [4,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93] | Low cost. No serious side effects. | Requires practitioners to have a high level of professional skills. No internationally standardized training program. The unique smell of traditional Chinese medicine may reduce patients’ treatment adherence. |

| Chinese herbal medicine | [94,95,96] | |||

| Comprehensive therapy | [97,98,99] | |||

| Neuroregulation | Exogenous neuromodulation | [100,101,102,103] | Passive regulation allows for precise targeting. Active regulation involves high participant engagement and personalization. | High cost. High technical requirements. No standardized treatment protocols. |

| Endogenous neuromodulation | [104,105,106,107] | |||

| CAM | Music therapy | [108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | Low risk and patient-friendly. | Individual differences and personalized needs. |

| Animal-assisted intervention | [120,121,122,123,124] | |||

| Exercise intervention | [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hai, Y.; Bai, S.; Qiao, H.; Li, D.; Wang, D.; Xia, M. A Review of Therapeutic Approaches for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121280

Hai Y, Bai S, Qiao H, Li D, Wang D, Xia M. A Review of Therapeutic Approaches for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121280

Chicago/Turabian StyleHai, Yang, Saihan Bai, Huiting Qiao, Deyu Li, Daifa Wang, and Meiyun Xia. 2025. "A Review of Therapeutic Approaches for Autism Spectrum Disorder" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121280

APA StyleHai, Y., Bai, S., Qiao, H., Li, D., Wang, D., & Xia, M. (2025). A Review of Therapeutic Approaches for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121280