1. Introduction

Anxiety disorders are one of the main categories of mental disorders, the essence of which is inadequate emotional reactions resulting from difficulties in adapting to the environment or a specific situation. The result of these disorders is often significant psychological discomfort and cognitive impairment [

1]. Social anxiety disorder is characterized by intense and persistent fear or anxiety, triggered by one or more social situations in which the individual may be observed by other people. This fear is most often associated with the fear of negative social evaluation, embarrassment, or humiliation. People suffering from this disorder often avoid social situations or endure them with high tension and anxiety, leading to a significant deterioration in their functioning in the social sphere [

2]. An important diagnostic criterion is the disproportionality of the perceived fear in relation to the actual threat and its persistence for at least six months. Avoidance of social situations or intense fear of them causes clinically significant functioning disorders in social, educational or professional areas [

3].

Previous studies indicate significant negative correlations between the severity of anxiety symptoms and the tendency to avoid social situations in the course of social anxiety disorder and the level of social support received [

4]. These results suggest that social support may play an important buffering role in the symptoms of this disorder. The concept of social support is multidimensional and includes various forms of interpersonal interaction. The mechanisms of its impact on the functioning of an individual are complex and may include emotional, informational and instrumental aspects [

5].

The concept of role-playing as a therapeutic form in the treatment of anxiety disorders was first described as early as the 1940s. Andrew Salter, in his work

Conditioned Reflex Therapy [

6], pointed to the potential of this method in the context of behavior modification. Since then, numerous studies have been published on the use of role-playing methods in therapy, for example, Social Skills Training (SST), in the treatment of anxiety disorders, many of which have been empirically verified in recent years [

7].

In the literature on the subject, four basic components of social skills are distinguished [

8]: non-verbal skills—including eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, body posture and interpersonal distance; verbal content—referring to the adequacy of the utterance, and the accuracy of the message in relation to the situation and the topic of conversation; paralinguistic features—such as the tone, pitch and intensity of the voice, and intonation, fluency and clarity of speech; interactive balance—including the ability to react to the interlocutor, and the length of the speech and reaction delay. Social Skills Training can therefore be defined as the systematic practice of the behaviors that make up the above components. SST is a flexible method that can be adapted to the individual needs and abilities of the participants, which translates into the effectiveness of this method [

9]. The most common form is group classes, which are conducive to modeling behavior and learning through observation and interaction with other participants.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in using gamification as an innovative approach not only to therapy but also to mental health prevention, both in children and adults. New interventions are designed based on recognized therapeutic methods, such as the above-described Social Skills Training, the exposure method, cognitive–behavioral therapy, as well as gamification mechanisms, which promotes their accessibility, scalability, and participant engagement [

10]. In this context, special importance is given to co-op role-playing games, known as role-playing games (RPGs) or TTRPGs (Tabletop Role-Playing Games). These are multiplayer games based on social interaction, collaborative decision-making, and active role-playing, conducted according to pre-established rules [

11]. Games of this type allow you to modify their structure and adapt the elements of the game to the individual needs of the participants. Another important advantage is the ability to react in real time, use reward systems, score, and monitor progress, which is conducive to increasing involvement in the therapeutic process. Preliminary research results suggest that RPGs can support the development of social skills, increase emotional self-awareness, and support the internalization of new, more adaptive behavior patterns [

10].

Although the therapeutic potential of RPGs is increasingly being described in the international literature, most research to date has been exploratory or descriptive. To date, most analyses of RPGs in mental health settings have been based on case studies or small qualitative studies, and only a few studies have systematically measured pre- and post-intervention outcomes [

12]. Furthermore, data indicate that RPGs can be used as an active intervention aimed at reducing anxiety. In a pilot study [

13] involving six participants, they found that RPG sessions have promising therapeutic potential for addressing anxiety symptoms. Research also indicates that role-playing games provide a safe, structured environment conducive to practicing social skills and developing socio-emotional competencies and can be easily adapted for interventions for anxiety disorders [

14]. Current literature [

15,

16,

17] indicates that the use of role-playing games is an effective intervention not only for social anxiety, but also for reducing depressive symptoms, social isolation, and working with individuals on the autism spectrum—both in clinical settings (as a complement to cognitive–behavioral therapy) and non-clinical settings. These games create a safe environment in which participants can confront situations they previously avoided and develop empathy and emotion regulation skills.

Difficult situations created by the “Game Master” can reflect participants’ everyday experiences [

16]. Through role-playing and supportive group dynamics, players have the opportunity to reframe maladaptive behavior patterns into more constructive ones and transfer them to real-life functioning. Collaborative narrative creation fosters bonding, group solidarity, and a sense of security, which provides a foundation for emotional and social change [

18]. The literature also highlights the similarity of RPGs to techniques used in Social Skills Training (SST), where role-playing is a key element [

19]. RPGs can serve as a transitional stage in exposure therapy, enabling the simulation of anxiety scenarios in a safe environment [

20]. Although some researchers report that participation in these games promotes the development of assertiveness, conflict resolution, emotion regulation, and interpersonal communication, despite a growing number of publications, few studies address the actual effectiveness of these interventions [

21].

In the Polish context, research on the use of role-playing games as a form of psychological or social support is still very limited. Although RPGs are gaining popularity as a form of entertainment and social activity, their targeted use in a therapeutic or paratherapeutic context has not yet been empirically investigated. This study aims to fill this gap by assessing the potential of RPG sessions as an alternative form of support for individuals with social anxiety disorder. By collecting pre- and post-intervention data from 30 participants, this study represents one of the largest quantitative studies in this field, in the context of research on the use of TTRPGs in the treatment of social anxiety disorder in the Polish setting.

The aim of this study is to assess the potential of role-playing games as an alternative method to support the treatment of social anxiety disorder. It is assumed that the use of this form of intervention can contribute to the reduction of anxiety symptoms and avoidance of social situations, as well as act as social support by enabling safe and controlled participation in group interactions. This is a pre–post single-group design with different frequency conditions.

3. Results

Analysis of the ISSB scores before the intervention shows that higher mean values of social support were observed in the groups from condition A2 (group meetings once every two weeks).

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the ISSB test results prior to participation in the experiment.

The analysis of the ISSB values after participation in the study indicates an increase in the received social support in both conditions. Greater improvement was observed in group A2 (group meetings once every two weeks).

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for the ISSB test scores after participation in the study.

Analysis of the level of social anxiety before the intervention shows that a higher level of anxiety was noted in group A1 (group meetings once a week). The results of the Shapiro–Wilk test indicate that the groups in condition A2 (group meetings once every two weeks) show deviations from normality (

p < 0.05), which suggests that the results in this condition should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale scores prior to participation in the study.

Analysis of the results after the intervention indicates a significant reduction in social anxiety in all groups. A greater reduction was noted in the groups from condition A2 (group meetings once every two weeks).

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for the results of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale after participation in the study.

Table 6 presents the results of the dependent samples

t-test for the measures of the four aspects of social support (emotional support, informational support, instrumental support, and evaluative support) and the overall score measure in the two conditions (before and after participation in the study) of the groups from condition A1, i.e., participating in group sessions once a week. All tests, except the measure of evaluative support, have

p values < 0.05, suggesting significant differences between conditions. The evaluative support score (

p = 0.095) does not reach statistical significance. The overall outcome measure (

p = 0.016, d = −0.618) has the largest effect size, meaning that the difference between pre- and post-study scores is not only significant but also has a medium effect size.

Figure 1 presents a more detailed comparison of the measurement results,

t-test values, and Cohen’s d effect for the above five variables. In each category, the post-intervention measurement values are statistically higher than the pre-intervention measurement values, indicating an increase in the receipt of social support after participation in the study. These results suggest a beneficial effect of interactions with other experimental participants on the amount of social support received by the subjects. Cohen’s d value is negative, indicating a moderate effect size. The largest difference was in the overall score.

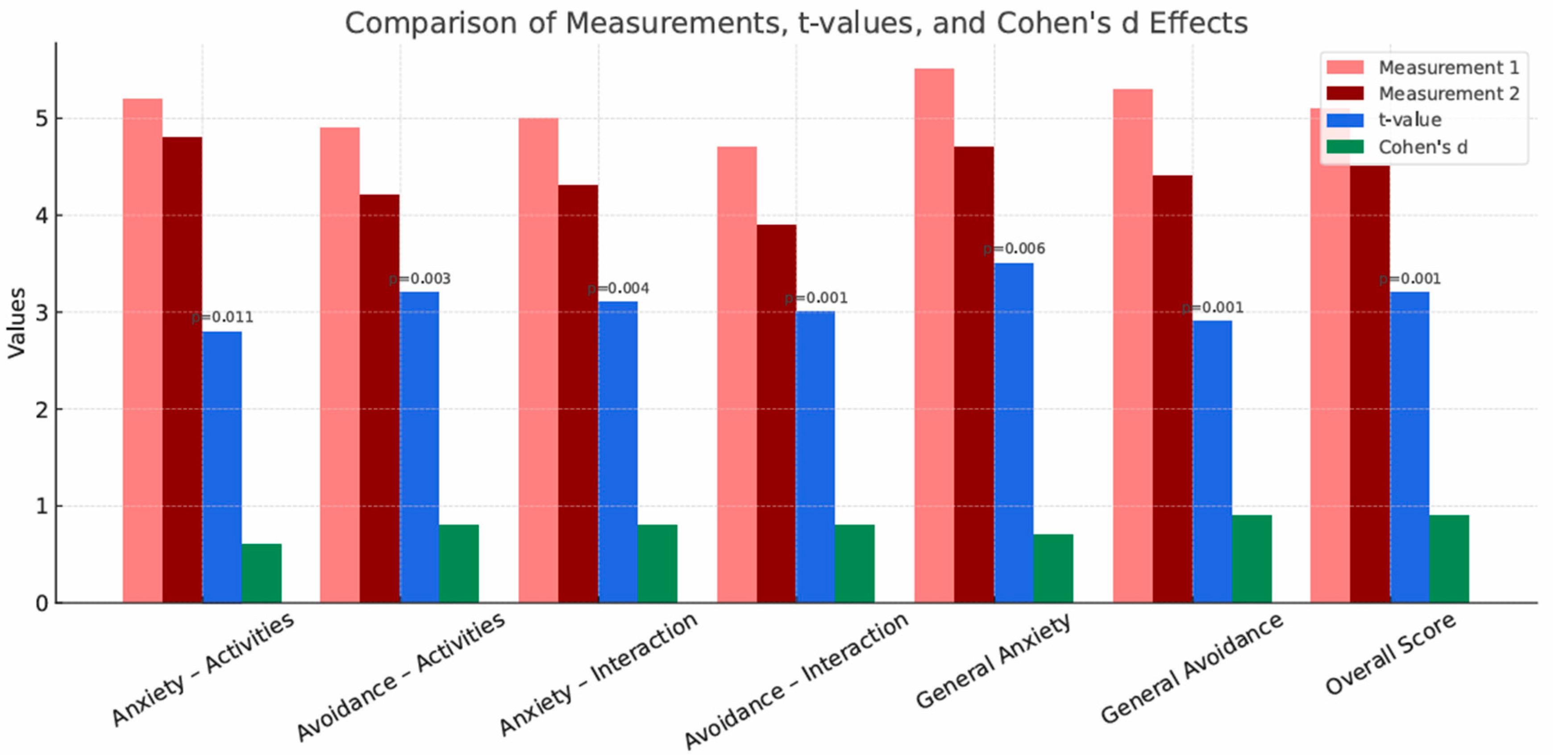

Table 7 presents the results of the paired-samples

t-test comparing the various measures of anxiety and avoidance between the two conditions (before and after participation in the study) for the groups participating in the once-weekly group sessions (A1). After participating in the study, participants showed less avoidance of social interactions than before participating in the study. There was a very strong effect on the general avoidance scale, meaning that participants were less likely to avoid social situations than before participating in the study. Social interaction anxiety also decreased significantly after participation in the study. Similarly, anxiety was related to performing activities, but with a smaller effect. The

p < 0.05 result indicates statistically significant differences.

Figure 2 presents a comparison of the measurement scores, t values, and Cohen’s d effects for the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale measures across participants attending weekly group sessions. In each category, the values in Measurement 2 are lower than in Measurement 1, indicating a decrease in anxiety and avoidance after participation in the study relative to the measurements before participation in the study. This suggests that regular social interaction and the social skills training elements included in such activities had an impact on reducing anxiety related to social situations and reducing the frequency of avoiding them. Cohen’s d values indicate a medium-to-large effect size, which allows us to conclude that there was a significant reduction in anxiety and avoidance. All

p values are <0.05, which indicates statistically significant differences.

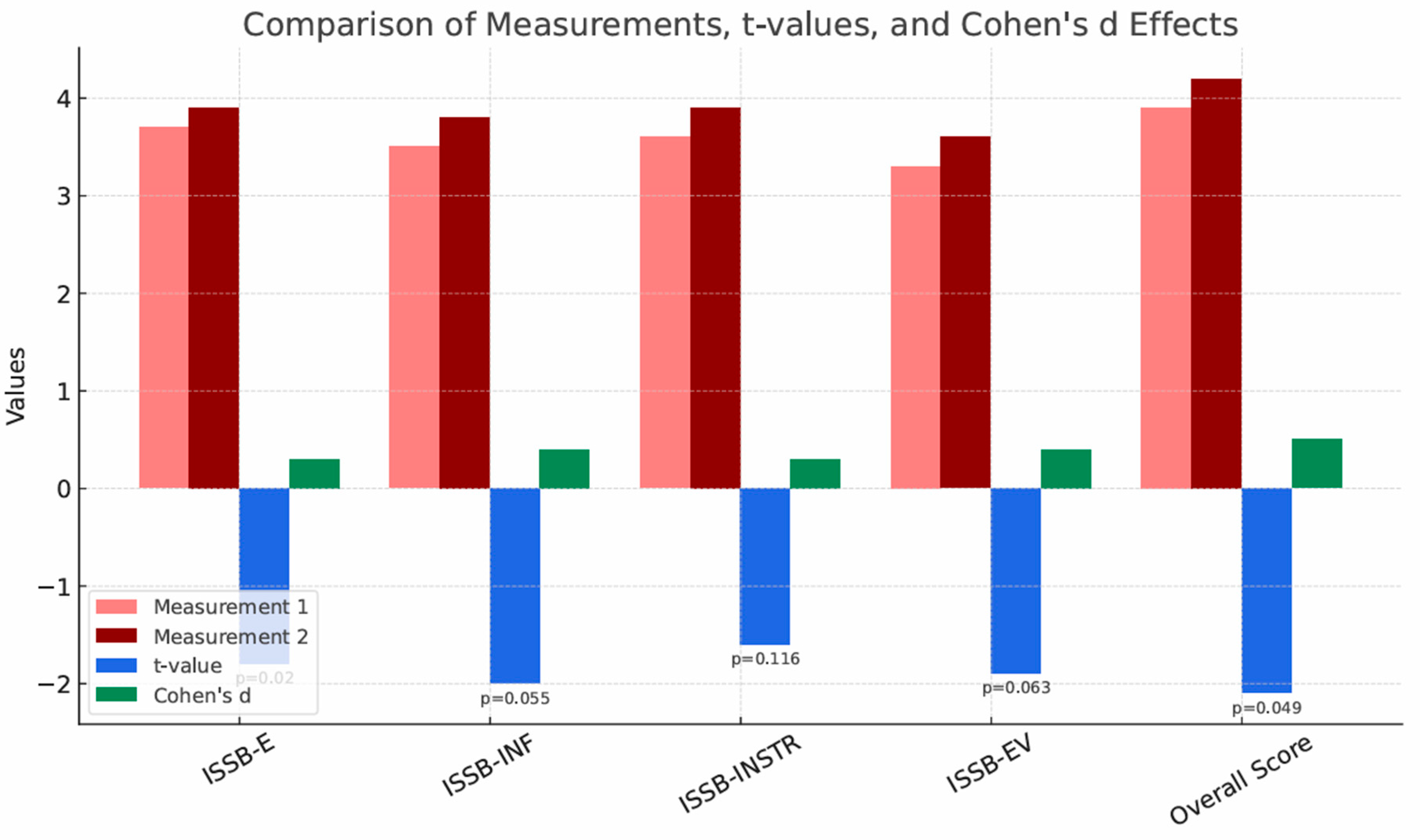

Table 8 presents the results of the dependent samples

t-test for the measures of the four aspects of social support (emotional support, informational support, instrumental support, and evaluative support) and the total score measure in the two conditions (before and after participation in the study) for individuals participating in the biweekly group sessions. The results do not indicate statistically significant differences between the measures of emotional and instrumental support, but indicate significance at the level of a statistical tendency for the measures of informational and evaluative support. The only significant difference was in the overall score, but the effect size (d = −0.459) suggests only a moderate influence.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of measurement results, t-values, and Cohen’s d effects for the measures of social support. Measurement 2 values are slightly higher than Measurement 1 values, suggesting a small increase in values in the new condition. Cohen’s d effects are small, suggesting a weak effect of the change in condition. Only the overall score shows a significant difference (

p = 0.049), but the effect is weak. The results for informational and evaluative support indicate significance at the level of statistical tendency (

p = 0.055,

p = 0.063). The analysis of these measurements suggests that reducing the frequency of meetings in the group system causes a decrease in the amount of social support received.

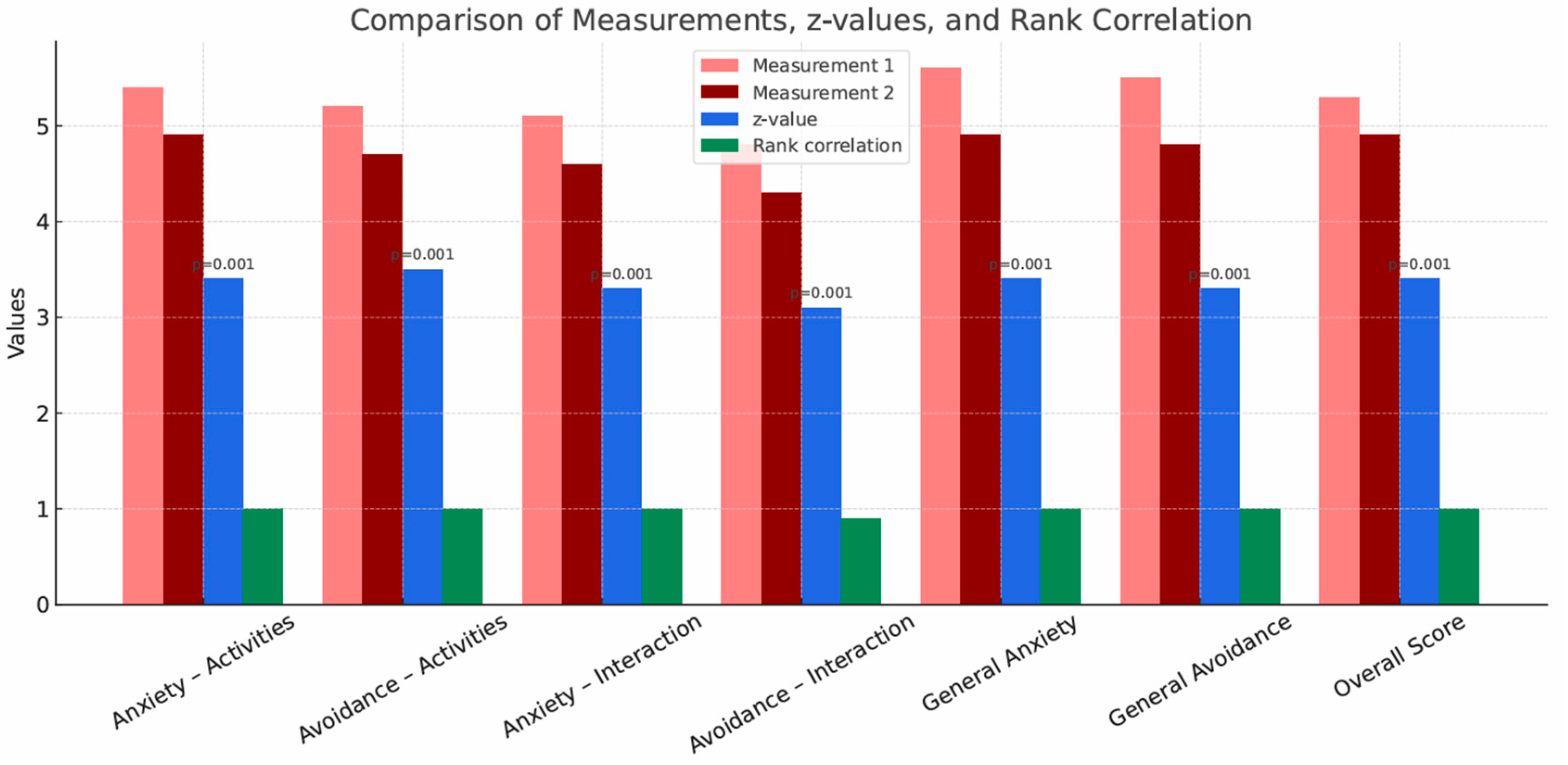

Table 9 presents the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for dependent samples, which compares the various measures of anxiety and avoidance between the two conditions (pre- and post-study) for participants attending the biweekly group sessions. This test is an alternative to the

t-test when the assumption of normality is not met. Each variable showed significant differences between conditions. The largest difference was for the measure ‘Avoidance—Activities’ (r = 1.000). All participants avoided social situations more on Measurement 1 than on Measurement 2. All

p values are less than 0.001, indicating strong differences. Rank correlations were high (0.900–1.000), indicating strong effects of changing the conditions. The post-intervention measurement condition was associated with significant decreases in anxiety and avoidance across both activities and interactions.

Figure 4 presents a comparison of the measurement scores, t values, and Cohen’s d effects for the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale measures across participants attending biweekly group sessions. In each category, Measurement 2 values are lower than Measurement 1, indicating a reduction in anxiety and avoidance in the post-intervention condition. These results suggest that participation in RPGs in a group setting is still associated with reduced anxiety and avoidance in participants despite the reduced frequency of encounters. The z-test values are high, indicating statistically significant differences, and the rank correlations are relatively high, suggesting consistency of the results. All

p values are <0.001, indicating highly significant differences between conditions.

4. Discussion

This paper analyzes the impact of participation in RPG sessions on the level of social anxiety and received social support. The study aimed to determine whether regular participation in such activities can contribute to reducing the level of social anxiety and increasing the amount of social support received in people with generalized social phobia. The study was conducted according to a methodological procedure involving two experimental groups. The groups participated in RPG sessions in different conditions: A1 (group meetings once a week) and A2 (group meetings once every two weeks).

The level of social anxiety in those participating in RPG sessions decreased, with a greater decrease observed in those participating in the weekly group system (24%). Cohen’s d effect values in this group indicate a large effect size (d > 0.8). In terms of social support, a higher increase was seen in those participating in the biweekly group (29%), suggesting that regular social interactions in a group may enhance feelings of support.

p values < 0.05 for all key comparisons indicate statistical significance of the results, confirming the effectiveness of the RPG intervention in reducing social anxiety and increasing support. The analysis of the collected data shows that participants reacted differently to participating in RPG sessions. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety at baseline reported some difficulty in fully engaging in narrative interactions, but their comfort gradually increased.

The results of the analyses conducted clearly indicate a significant improvement in the level of social anxiety experienced in all analyzed conditions. The statistical significance of the results in all cases indicates a consistent effect and suggests that the mechanisms present in RPG sessions—such as role-playing, safe exploration of social interactions, and gradual building of relationships—may effectively contribute to reducing this type of anxiety. A significant reduction in the level of avoidance of social situations was also found. Positive results indicate the beneficial effect of role-playing games on overcoming the tendency to avoid social contacts.

In the case of received emotional support, significant improvement was noted only in the condition of once-a-week group sessions. This distribution of results allows us to conclude that participation in RPG sessions may improve emotional social support, but this effect is not clear and may depend on additional factors, such as the length of participation, the intensity of the session or the nature of the group.

In the case of informational social support received, improvement was also noted only in the once-weekly group session condition. This suggests that participants of role-playing games gain access to knowledge, information and advice through contact with the group, especially in the first stages of integration, but the effects are greater with a greater frequency of meetings.

Similarly, for instrumental social support, only the once-weekly group session condition showed statistically significant improvement. These results suggest that the impact of participating in RPG sessions on this form of support may be limited or short-lived. It is possible that building a network of instrumental support (e.g., material or practical assistance) requires a longer period of participation and stronger ties than those formed at the initial stage. Analysis of overall social support indicates improvement in both conditions.

The mechanisms underlying these changes can be linked to the nature of the RPG sessions themselves. Collaborative narrative creation fosters a microculture that fosters trust and cooperation [

18], and players have the opportunity to experiment with decisions and behaviors they fear in everyday life. This type of “safe exposure” is important for emotional and social learning processes [

23]. RPGs can serve as an intermediate step in exposure therapy [

20]—players confront their own fears in a controlled environment, which promotes a gradual increase in their sense of safety and agency. Previous studies [

15,

17] have demonstrated the development of empathy, improved problem-solving skills, and increased self-esteem as a result of participating in role-playing games. The reduction in social avoidance observed in this study can therefore be interpreted as a result of repeated practice of interpersonal behaviors in a narrative context—consistent with the concept of social skills training [

19]. Participants gradually increased their engagement, which can be linked to the development of trust and openness [

18]. It is also worth noting that the phenomenon of the “interpenetration” of the game world and reality, described earlier by Polkinghorne [

18], could additionally contribute to the consolidation of positive changes—participants often related the behavior of their characters to their own experiences, which could serve as a metaphorical decision-making training.

The results of this study are consistent with previous literature reports. The research conducted by Kipper and Ritchie [

24] indicates the therapeutic potential of RPGs, especially in terms of strengthening self-esteem and reducing anxiety in social situations. Similarly, Ott [

11] pointed out the usefulness of this method in developing skills to cope with anxiety. Henrich and Worthington’s [

25] research suggests that participation in RPGs may have a beneficial effect on cognitive processes and emotion regulation. Additionally, Olivares-Olivares et al.’s [

7] research has shown that social skills training combined with group interaction significantly reduces symptoms of social anxiety. Lees [

26], in his work, indicated a clear improvement in socialization skills associated with participation in RPG-type role-playing games and the possibility of using this element as a basis for combating social anxiety. In addition, Abbott et al. [

17] indicate an increase in the self-confidence and confrontation skills of people participating in RPG-type role-playing games. It is worth noting, however, that compared to previous studies, this experiment included people who had no previous contact with RPGs, which makes the obtained results particularly interesting in the context of first contact with this type of activity.

Despite the general consistency of the results with the literature, some discrepancies were observed. In some cases, no significant changes in the level of social anxiety were observed, which may be due to individual differences between participants, including the level of motivation, personality, or the intensity of the experienced anxiety. It is also possible that the duration of the study was too short to observe stability in the maintenance of the changes that occurred. For example, the research of Poniah and Hollon [

27] suggests that exposure alone is not enough, and long-term reinforcement of the effects of therapy through additional behavioral techniques is crucial.

The study had several significant limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Primarily, the study sample size was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of the results to a broader population. Furthermore, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to clearly determine whether the observed changes were a true effect of the intervention or could have been due to other factors. Another limitation was the lack of a repeat measurement at least three months after the intervention, which prevented assessment of the sustainability of the achieved effects over time. The low randomness in participant selection and the need to divide participants into subgroups based on availability and willingness to participate may also have impacted the study’s internal reliability. The difficulty in recruiting volunteers stemmed from the fact that participation required a three-month commitment, further limiting the representativeness of the sample.

Taking into account the obtained results, it is worth considering several directions for future research. First of all, the duration of the intervention should be extended to better assess the long-term effects of participation in RPGs. Moreover, an important extension could be to include a comparison of the effects of RPGs with other forms of social skills training, such as classic psychoeducational workshops or cognitive–behavioral therapy. It is also worth considering examining the influence of moderating factors, such as the level of neuroticism or the specificity of the social experiences of the respondents. It is also worth considering re-testing participants several months after completing the study to monitor the maintenance of the effects of participation.

In summary, the results of this study indicate the potential effectiveness of RPGs as an intervention to reduce social anxiety and enhance social support. The results provide a basis for further research in this area and suggest the possibility of implementing RPGs as a complementary therapeutic tool for people with anxiety disorders.

Although the study was not a fully randomized controlled trial, the reporting structure followed the CONSORT 2025 [

28] recommendations to ensure transparency and completeness. The CONSORT checklist is available in the

Supplementary Materials.