Figure 1.

Orbital fractures represent up to 50% of all facial skeletal injuries and have recently emerged as a potential consequence of e-scooter–related accidents [

1,

2,

3]. In contrast, penetrating head injuries are rare, accounting for approximately 0.4% of all head trauma cases, and are most commonly associated with falls, motor vehicle collisions, and explosions. Among these, transorbital penetrating injuries represent up to 24% of adult penetrating head injuries [

4,

5]. Isolated cases of penetrating intracranial injuries caused by bicycle brake handles have been reported in the literature, unfortunately, most with fatal outcomes [

6,

7,

8]. A 76-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with a transorbital intracranial injury caused by an e-scooter brake handle. The patient was not riding the e-scooter but sustained the injury after a same-level fall onto a shared electric scooter. On admission, he was conscious but intoxicated, with a blood alcohol concentration of 2.13‰ (according to the hospital laboratory), and had no recollection of the incident. (

a) The fire brigade team cut the brake handle from the handlebar, and the remaining portion was stabilized with bandages for transport and for the CT-angiography (CTA) examination. (

b) Prior to surgery, the brake handle required further dismantling to allow for craniotomy. The patient was transferred to the operating theatre. A hemi-coronal incision was made in the left frontal region, extending across the midline. A left pterional–parasagittal craniotomy was performed. The site of penetration of the foreign body through the orbital roof into the left frontal lobe was identified, and the foreign body was removed under direct visual control. Following removal, cerebrospinal fluid (CFS) outflow from the lateral ventricle was observed. Inspection of the surgical field revealed no evidence of bleeding, and the ventricle was closed using TachoSil. After removal of the foreign body, the left eyeball appeared intact, with a narrow and symmetrical pupil. The orbit was inspected through the wound in the upper eyelid. Apart from minor soft tissue injuries, no injury to the extraocular muscles was detected. Reconstruction of the anterior cranial fossa was then performed. The orbital roof was repositioned, and a “sandwich” dural repair was completed using TachoSil and tissue glue. The bone flap was reduced and secured with sutures. During hospitalization, the patient underwent endoscopic revision to assess for CSF leakage into the nasal cavity [

9]. Due to the extent of brain injury, the patient subsequently required admission to the psychiatric ward.

Figure 1.

Orbital fractures represent up to 50% of all facial skeletal injuries and have recently emerged as a potential consequence of e-scooter–related accidents [

1,

2,

3]. In contrast, penetrating head injuries are rare, accounting for approximately 0.4% of all head trauma cases, and are most commonly associated with falls, motor vehicle collisions, and explosions. Among these, transorbital penetrating injuries represent up to 24% of adult penetrating head injuries [

4,

5]. Isolated cases of penetrating intracranial injuries caused by bicycle brake handles have been reported in the literature, unfortunately, most with fatal outcomes [

6,

7,

8]. A 76-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with a transorbital intracranial injury caused by an e-scooter brake handle. The patient was not riding the e-scooter but sustained the injury after a same-level fall onto a shared electric scooter. On admission, he was conscious but intoxicated, with a blood alcohol concentration of 2.13‰ (according to the hospital laboratory), and had no recollection of the incident. (

a) The fire brigade team cut the brake handle from the handlebar, and the remaining portion was stabilized with bandages for transport and for the CT-angiography (CTA) examination. (

b) Prior to surgery, the brake handle required further dismantling to allow for craniotomy. The patient was transferred to the operating theatre. A hemi-coronal incision was made in the left frontal region, extending across the midline. A left pterional–parasagittal craniotomy was performed. The site of penetration of the foreign body through the orbital roof into the left frontal lobe was identified, and the foreign body was removed under direct visual control. Following removal, cerebrospinal fluid (CFS) outflow from the lateral ventricle was observed. Inspection of the surgical field revealed no evidence of bleeding, and the ventricle was closed using TachoSil. After removal of the foreign body, the left eyeball appeared intact, with a narrow and symmetrical pupil. The orbit was inspected through the wound in the upper eyelid. Apart from minor soft tissue injuries, no injury to the extraocular muscles was detected. Reconstruction of the anterior cranial fossa was then performed. The orbital roof was repositioned, and a “sandwich” dural repair was completed using TachoSil and tissue glue. The bone flap was reduced and secured with sutures. During hospitalization, the patient underwent endoscopic revision to assess for CSF leakage into the nasal cavity [

9]. Due to the extent of brain injury, the patient subsequently required admission to the psychiatric ward.

![Brainsci 15 01160 g001 Brainsci 15 01160 g001]()

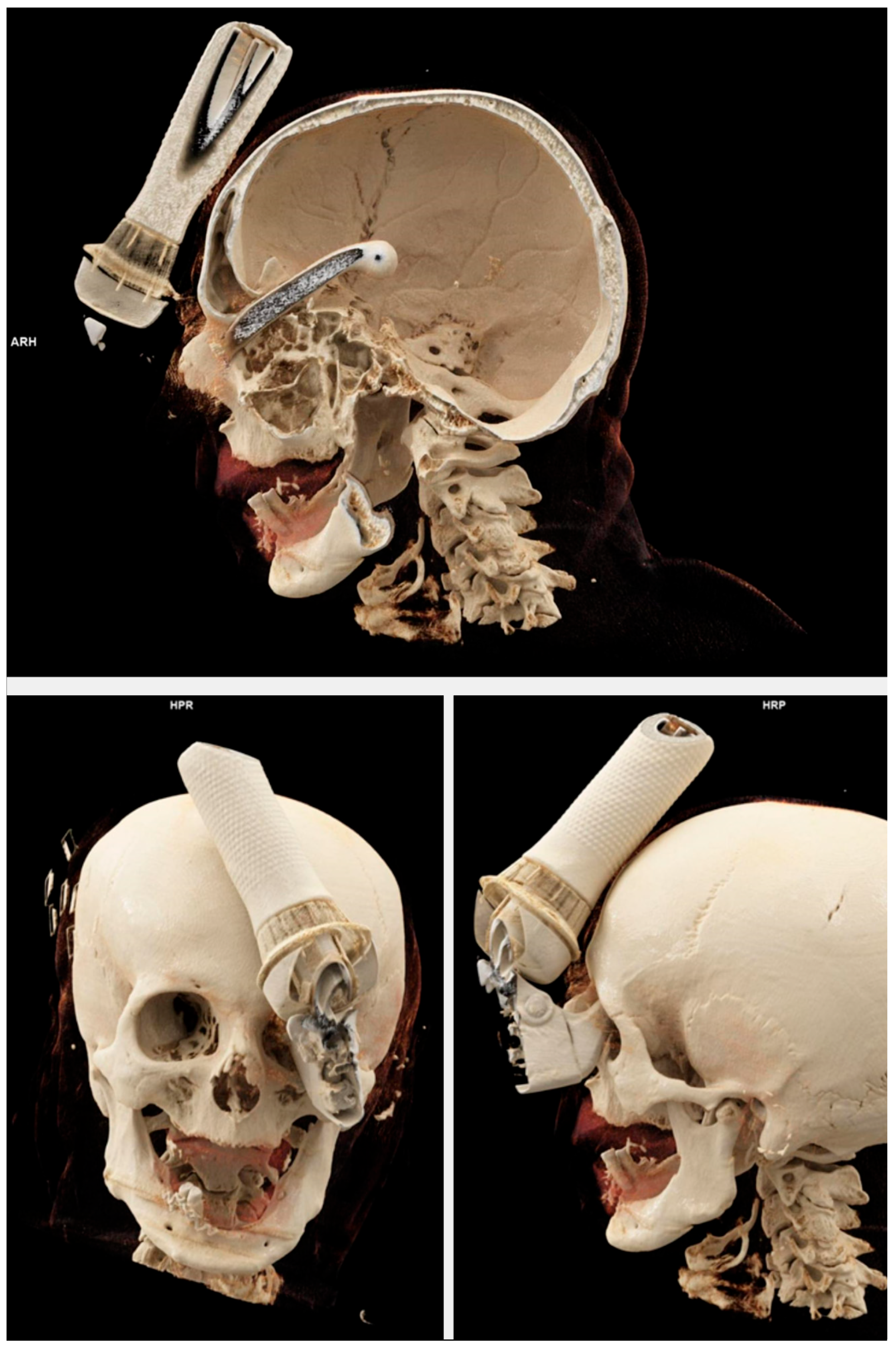

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional bony reconstruction from CTA demonstrating a transorbital intracranial injury caused by an e-scooter brake handle.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional bony reconstruction from CTA demonstrating a transorbital intracranial injury caused by an e-scooter brake handle.

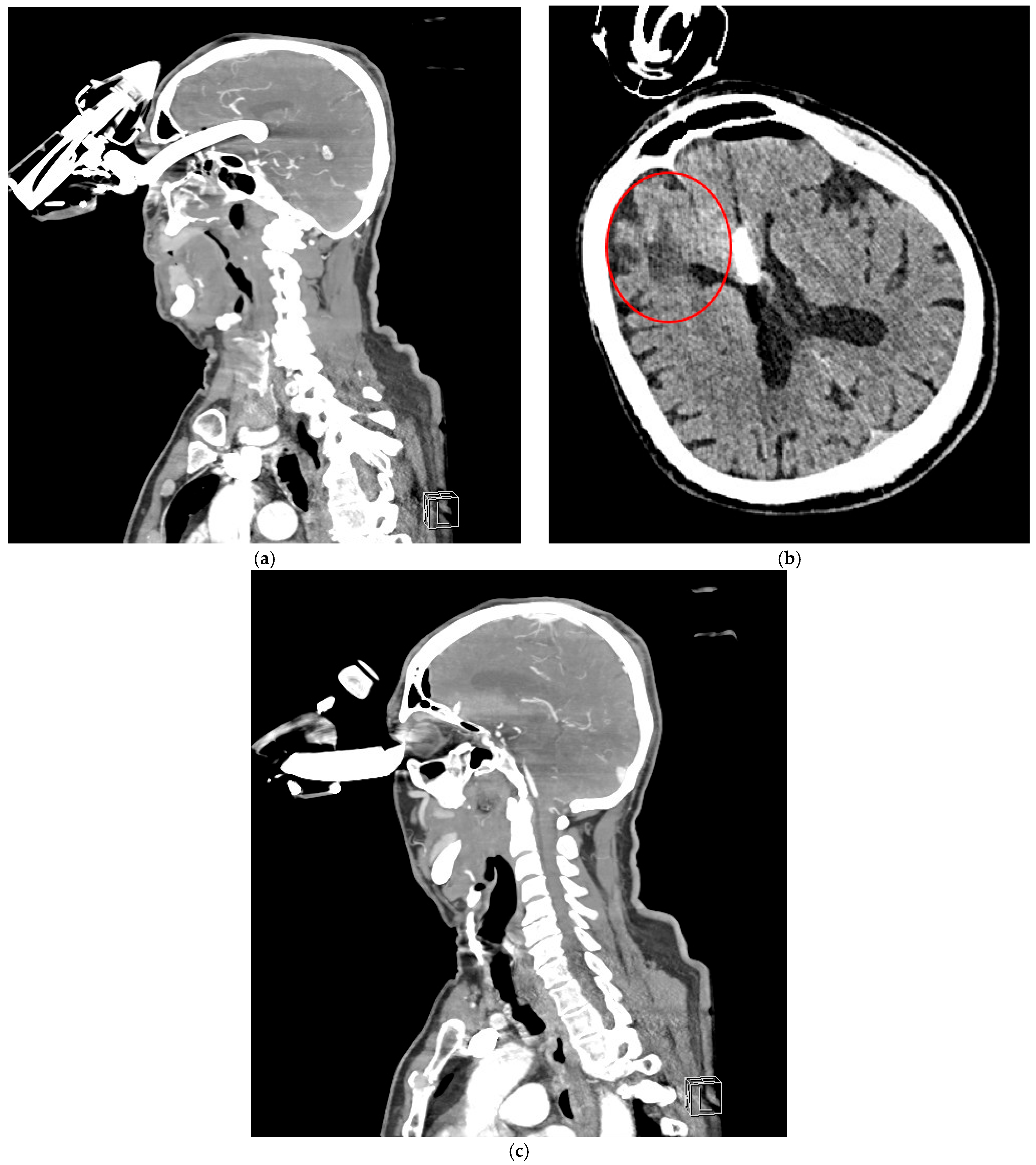

Figure 3.

CTA revealed a foreign body penetrating the left orbit into the anterior cranial fossa, extending into the third ventricle to a depth of approximately 64 mm (a). The anterior cerebral arteries were visualized along the foreign body, both running on its left side. No significant intracranial hemorrhage was observed. Additionally, features of porencephaly were noted, likely resulting from a previous injury to the right frontal lobe (red circle—the patient had a history of two head CT scans at our hospital, in 2012 and 2014, which showed evidence of porencephaly) (b). The ventricular system was normal in size and position, without displacement or enlargement. (c) The left eyeball was displaced laterally and inferiorly, compressed by the foreign body, but showed no evidence of direct injury.

Figure 3.

CTA revealed a foreign body penetrating the left orbit into the anterior cranial fossa, extending into the third ventricle to a depth of approximately 64 mm (a). The anterior cerebral arteries were visualized along the foreign body, both running on its left side. No significant intracranial hemorrhage was observed. Additionally, features of porencephaly were noted, likely resulting from a previous injury to the right frontal lobe (red circle—the patient had a history of two head CT scans at our hospital, in 2012 and 2014, which showed evidence of porencephaly) (b). The ventricular system was normal in size and position, without displacement or enlargement. (c) The left eyeball was displaced laterally and inferiorly, compressed by the foreign body, but showed no evidence of direct injury.

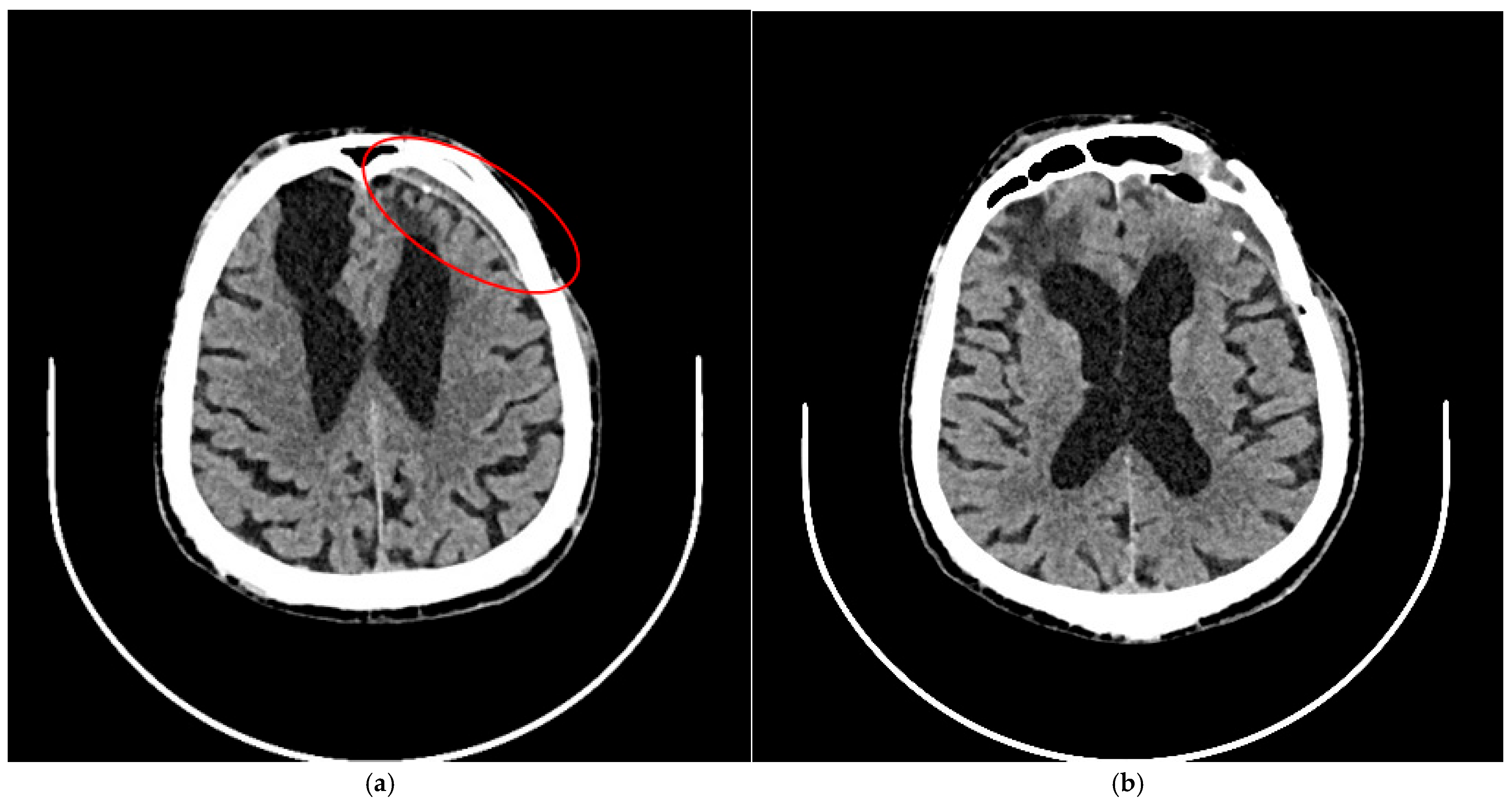

Figure 4.

A follow-up CT scan six months after treatment showed no evidence of new intracranial hemorrhage. (a) A narrow chronic subdural hematoma was noted (red circle). (b) Extensive hypodense post-traumatic changes were observed at the base of both frontal lobes. The ventricular system was significantly enlarged and asymmetrical, with evidence of right-sided retraction. There was no displacement of midline structures.

Figure 4.

A follow-up CT scan six months after treatment showed no evidence of new intracranial hemorrhage. (a) A narrow chronic subdural hematoma was noted (red circle). (b) Extensive hypodense post-traumatic changes were observed at the base of both frontal lobes. The ventricular system was significantly enlarged and asymmetrical, with evidence of right-sided retraction. There was no displacement of midline structures.

Figure 5.

Clinical examination one year after the injury revealed atrophy of the orbital fat in the superior quadrants of the left orbit, accompanied by mild eyelid ptosis. The patient had a history of bilateral cataract surgery before injury. Visual acuity was 0.9 in the right eye (OD), measured without and with correction (NC/CC), and 0.32 in the left eye (OS) with correction using pinhole testing. Fundus examination revealed pink optic discs with clearly defined margins, maculae without reflex, and retinal vessels appropriate for age in both eyes. The retinas were attached in the areas accessible to examination. No diplopia was noted. Neurocognitive assessment revealed deficits primarily affecting auto- and allopsychic orientation, recent memory, auditory encoding of new information, and the selective retrieval of previously learned material from long-term memory. Memory gaps were frequently filled with confabulations. In addition, verbal fluency was impaired, likely secondary to executive dysfunction.

Figure 5.

Clinical examination one year after the injury revealed atrophy of the orbital fat in the superior quadrants of the left orbit, accompanied by mild eyelid ptosis. The patient had a history of bilateral cataract surgery before injury. Visual acuity was 0.9 in the right eye (OD), measured without and with correction (NC/CC), and 0.32 in the left eye (OS) with correction using pinhole testing. Fundus examination revealed pink optic discs with clearly defined margins, maculae without reflex, and retinal vessels appropriate for age in both eyes. The retinas were attached in the areas accessible to examination. No diplopia was noted. Neurocognitive assessment revealed deficits primarily affecting auto- and allopsychic orientation, recent memory, auditory encoding of new information, and the selective retrieval of previously learned material from long-term memory. Memory gaps were frequently filled with confabulations. In addition, verbal fluency was impaired, likely secondary to executive dysfunction.

![Brainsci 15 01160 g005 Brainsci 15 01160 g005]()

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and M.G.; methodology, P.S. and J.P.; software, K.G., J.B. and P.S.; validation, J.B. and G.W.-P.; formal analysis, M.G. and K.N.; investigation, P.S. and M.G.; resources, P.S. and J.B.; data curation, P.S., J.P. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. and M.G., writing—review and editing, M.G., P.S. and G.W.-P.; visualization P.S., J.B. and M.G.; supervision G.W.-P.; project administration, P.S. and K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jagiellonian University (1072.6120.230.2021, dated 29 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Michalik, W.; Toppich, J.; Łuksza, A.; Bargiel, J.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Gontarz, M. Exploring the Correlation of Epidemiological and Clinical Factors with Facial Injury Severity Scores in Maxillofacial Trauma: A Comprehensive Analysis. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1532133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sritharan, R.; Blore, C.; Arya, R.; McMillan, K. E-scooter-related facial injuries: A one-year review following implementation of a citywide trial. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 234, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koryczan, P.; Zapała, J.; Gontarz, M.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Surgical Treatment of Enophthalmos in Children and Adolescents with Pure Orbital Blowout Fracture. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 63, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mzimbiri, J.M.; Li, J.; Bajawi, M.A.; Lan, S.; Chen, F.; Liu, J. Orbitocranial Low-Velocity Penetrating Injury: A Personal Experience, Case Series, Review of the Literature, and Proposed Management Plan. World Neurosurg. 2016, 87, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreckinger, M.; Orringer, D.; Thompson, B.G.; La Marca, F.; Sagher, O. Transorbital Penetrating Injury: Case Series, Review of the Literature, and Proposed Management Algorithm. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sukul, B.; Das, S.K. Fatal Transorbital Head Injury by Bicycle Brake Handle. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2009, 16, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poroy, C.; Cibik, C.; Yazici, B. Traumatic Globe Subluxation and Intracranial Injury Caused by Bicycle Brake Handle. Arch. Trauma Res. 2016, 5, e33405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathish, K.; Chaudhari, V.A.; Murthy, A.S. Fatal Transorbital Intracranial Penetrating Injury Due to a Bicycle Brake Handle. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2018, 39, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraczek, M.; Guzinski, M.; Morawska-Kochman, M.; Nelke, K.H.; Krecicki, T. Nasal Endoscopy: An Adjunct to Patient Selection for Preoperative Low-Dose CT Examination in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2016, 45, 20160173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).