Abstract

Background/Objectives: Despite efforts, schizophrenia remains a difficult disease to treat for cognitive, positive, negative, and mood symptoms. In the present review, we explore existing data on the ameliorating effects of neurocognitive rehabilitation and the diverse symptomatology of the disorder. Methods: This systematic review has been registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD 420251154674). Following PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a search in PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct database from inception to 14 July 2025. The methodological quality assessment was made by applying the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. Results: Of the 1001 records screened for eligibility, thirty-five studies were identified for data extraction and synthesis. Of these, seven had a low risk of bias, and seven had a high bias risk. The effects of cognitive remediation on the symptoms of schizophrenia were varied. There are consistently positive effects on negative symptoms, but the findings are mixed regarding other domains of symptomatology. The therapeutic effect on positive psychotic symptoms correlated with the severity of symptoms at baseline. Efficacy for mood and anxiety symptoms is controversial, with a comparable number of studies yielding contradicting results. Conclusions: Cognitive remediation has been shown to represent a significant therapeutic tool for schizophrenia symptoms. The method‘s efficacy seems well-established for negative symptoms, whereas the effects on positive psychotic, mood, and anxiety symptoms, although promising, are currently mixed. More high-quality research targeting patient populations where the symptoms studied are more prominent is needed to clarify the effectiveness of the intervention for distinct dimensions of schizophrenic symptomatology.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating disorder, imposing a heavy burden on patients, families, and society [1]. The introduction of antipsychotic agents brought forth a revolution in the treatment of the disease, succeeding in bringing many patients living in asylums back to the community [2]. Still, achieving recovery or even symptomatic remission remains elusive to this day, and even when remission is achieved, many patients experience residual or persisting symptoms, cognitive decline, and functional failure [3]. Cognitive deficits are a core characteristic of schizophrenia and notably resistant to treatment. They include deficits in working and verbal memory, processing speed, attention, executive function, and reasoning, among others [4]. Deficits in social cognition are also apparent and highly detrimental; they seriously interfere with the ability of schizophrenic patients to communicate effectively and achieve or maintain social communication [5]. Medication, including antipsychotics as well as novel agents (d-cycloserine, memantine, and anticholinesterase inhibitors represent some examples), have proven ineffective or minimally effective [6]. However, besides cognitive symptoms, other symptom domains also tend to persist and often show resistance to available pharmaceutical agents, creating serious distress in patients’ lives and even frustration for families and treating clinicians [7].

These symptoms include positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations, negative symptoms, such as abulia, loss of interest, blunted affect, withdrawal, and anergia, mood symptoms, most usually depressive, and others. The latter cause serious distress, frustration, and suicidal thoughts or attempts in patients [8]. The situation is grim, and novel or additional therapies that can increase the therapeutic effect and outcome are more than welcome; their implementation is crucial and even necessary.

Cognitive remediation (CR) is a rehabilitative therapeutic procedure that takes advantage of the brain’s neuroplastic ability, essentially to increase the patient’s cognitive capacity and functional outcome. It has been practiced in a broad variety of medical conditions, beginning with traumatic brain injury, but it was quickly implemented in psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, for the treatment of cognitive deficits that are almost universally present in such patients [9].

Due to the important benefits of CR, this method has been included by the European Psychiatric Association in the treatment guidelines for cognitive deficits of schizophrenia [10]. Recent studies have shown a positive effect of CR on additional clinical symptoms, and it possibly represents an indispensable therapeutic modality for the management of patients with schizophrenia. The present review is a comprehensive overview of the efficacy of CR in treating clinical symptoms beyond the positive effects of medication and assists in increasing familiarity and confidence among clinicians for the benefit of their patients.

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct databases from inception to 14 July 2025. We used the following search string for all three databases screened for eligible articles: ((cognitive remediation) OR (cognitive rehabilitation) OR (cognitive training)) AND psychopathology OR delusions OR hallucinations OR negative OR depressive OR anxiety). Across databases, the search fields were title, abstract, and keywords. A search of the gray literature was not performed. Reference lists of relevant papers were searched manually for additional studies. Our aim was to provide data derived from original research. The following inclusion criteria were applied based on the PICO framework for systematic reviews. (1) Population: Samples consisting of patients with schizophrenia, diagnosed based on specific classification or operationalized criteria. (2) Intervention: An experimental group that underwent cognitive remediation to target specific cognitive deficits, whether computerized, paper-and-pencil, or otherwise. (3) Comparator: An RCT design where a control group and randomized allocation were utilized. The control group interventions included various treatments, such as pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or occupational therapy (a complete list of the control group interventions is presented in Table 1). (4) Outcome: Changes in cognitive and clinical symptoms assessed using relevant scales and explicitly reported. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study designs or article types other than original, i.e., case reports, conference proceedings, reviews, meta-analyses, study protocols, (2) study designs other than randomized controlled trials, (3) articles published in languages other than English, and (4) not specified or unclear reporting of cognitive and clinical outcomes. Articles were excluded at the full-text stage if (1) samples consisted of patients with multiple disorders from the schizophrenia spectrum within a group, including schizoaffective disorder, (2) the control group was unsuitable as a comparator, mainly because of a cognitive remediation intervention being implemented, or (3) there was no mention of the preferred method of diagnosis confirmation (e.g., DSM-V).

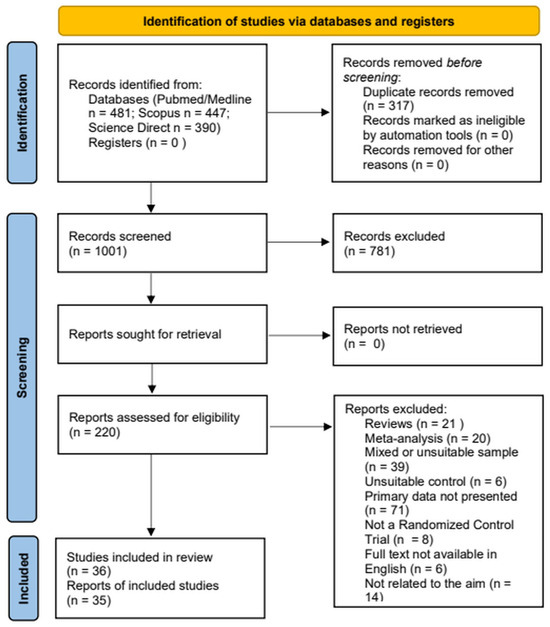

This systematic review is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD 420251154674). The review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews [11]. Abstract and full-text screening was conducted by two independent reviewers (MS and PS) using the Cadima evidence synthesis tool and database [12]; disagreement was resolved by consensus or by consulting with the supervisor of the study (LM). The flow diagram of the screening and selection of studies is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review, which included searches of PubMed/Medline, Science Direct, and Scopus electronic databases.

Data from included studies were extracted and organized into tables summarizing study characteristics, interventions, outcomes, and risk of bias. Supplementary Table S3 presents the effect size indices used—η2, ηp2, d, ES, total b—in a comprehensive manner to facilitate understanding. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the risk of bias of RCTs [13] (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Each study was evaluated across 13 criteria covering different sources of methodological bias. All included records were assessed independently by two reviewers (MS and PS); disagreement was resolved through consensus. A composite rating for every study was calculated as follows: studies meeting >70% of the criteria were rated “low” risk, those meeting 50–70% were rated “moderate” risk, and studies meeting <50% were rated as having a “high” risk of bias. A detailed breakdown of each study’s criterion rating is provided in Supplementary Table S4.

No attempts were made to retrieve missing data from the study authors. We considered missing information to reflect the authors’ reporting decisions; therefore, only the data available in the published reports were extracted.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

After database searches and screening, a total of 35 studies were included in the analysis (Table 1). Most studies were of moderate methodological quality; however, seven of them had low risk of bias [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Sample sizes ranged between 11 [21] and 270 [17], with the majority recruiting less than 100 patients. Interventions were diverse, including computerized or paper-and-pencil training, individually or in groups, virtual reality, and social cognition or metacognition components, whereas control groups received Treatment as Usual (TAU) with medication only or various types of psychosocial therapies, such as supportive therapy, music and dancing therapy, occupational rehabilitation, and others. Most studies explored dimensions of psychopathology by applying the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS), while some focused on depressive symptoms or anxiety. About one-third [17,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] examined clinical effects as a secondary outcome. Of the studies, 13 reported measures of effect sizes [16,22,25,28,30,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

3.2. Specific Symptom Outcomes

Positive symptoms were assessed with the use of the PANSS (positive subscale) or, rarely, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Present State Examination (PSE), or the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Of the studies that conducted these assessments (n = 34), only four [22,36,41,42] demonstrated a significantly superior effect of cognitive remediation over TAU or other rehabilitation (art therapy, physical training, occupational therapies) [41]. Only one [41] reported an effect size, which was found to be small. The sample of two studies consisted of inpatients, acutely ill patients [22], or patients in rehabilitation centers [41]. Duration of treatment was 4 to 24 weeks.

Table 1.

Studies assessing changes in clinical symptoms following cognitive rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Studies assessing changes in clinical symptoms following cognitive rehabilitation.

| Study | Country | Sample (Training/Control, Age, % Males, Setting) | Type of Intervention | Study Duration and Dose | Cognitive Functions Targeted | Control Group | Results | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gharaeipour and Scott, 2012 [43] | Iran | N = 42, 21/21 CR 29.81 ± 7.61 GST 27.62 ± 5.66 71.4%. Inpatients, consecutive admissions | Cognitive remediation | 1 h/session, 6 sessions/w, 40 h, 8 weeks | Attention, working memory, executive functions | Group supportive therapy | No significant differences in PANSS, BDI, BAI | Moderate |

| Zhu et al., 2021 [22] | China | N = 72, 22/24/26 CCT: 30 (25–39) CCT + MSST: 32 (26–41) Controls: 33 (26–41) 51.3% Inpatients, acute admissions, outpatients | Compensatory Cognitive Training combined with Medication Self-Management Skills Training; Compensatory Cognitive Training | CCT: 2 h/session, 2 sessions/w, 4 weeks CCT + MSST: CCT: 2 h/session, 2 sessions/w MSST: 2 h/ session, 3 sessions/w, 4 weeks | Prospective memory, conversational attention, task attention, verbal learning and memory, cognitive flexibility, problem solving, planning | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant group × time interaction for CCT + MSST compared with TAU in PANSS positive symptoms (MD = −0.101, p < 0.03, η2 = 0.211, 95% CI [−0.178, −0.025]) No significant difference between CCT + MSST and CCT or CCT and TAU | Moderate |

| Vita et al., 2011b [41] | Italy | N = 31, 16/15 IPT-cog: 34.6 (7.6) Treatment as Usual: 39.9 (8.6) 83.8% Inpatients from rehabilitation center | Integrated Psychological Therapy (IPT) | 45 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 24 weeks | Attention (selective and sustained), memory, conceptualization abilities, cognitive flexibility | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant difference on PANSS total score (IPT: 95.8 ± 14.4 → 66.7 ± 11.5; control: 94.0 ± 11.7 → 77.8 ± 14.9, p < 0.04) Significant difference in PANSS negative scores (IPT: 31.3 ± 6.4 → 21.6 ± 5.6; control: 28.8 ± 6.8 → 26.0 ± 8.4, < 0.001) | Moderate |

| Penadés et al., 2006 [15] | Spain | n = 60, 20/20/20 CRT 34.43 (8.3) CBT 35.84 (8.5) Treatment as Usual 38.30 (9.1) 63% Outpatients, chronic | Cognitive remediation therapy | 1 h/session, 2–3 sessions/w, 16 weeks, 40 sessions | Flexibility in thinking and information set maintenance, executive processes central to memory control, working memory, planning | CBT, Treatment as Usual (psychotropic medication) | Significant difference for the PANSS depression items (CBT: 10.9 ± 3.0 → 6.6 ± 1.9; CRT: 10.3 ± 3.3 → 116 ± 3.4); no significant differences for other subscales | Low |

| Vita et al., 2011a [16] | Italy | N = 84, 26/30/28 IPT-Cog: 37.15 ± 9.10 Cogpack: 36.87 ± 11.40 REHAB: 43.00 ± 7.76 69% Inpatients from rehabilitation centers | Integrated Psychological Therapy–Cognitive Remediation; Cogpack | 45 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 24 weeks | IPT-Cog: cognitive differentiation, social perception, verbal communication, social skills, and interpersonal problem solving; Cogpack: verbal memory, verbal fluency, psychomotor speed and coordination, executive function, working memory, attention, language and calculation skills | Rehabilitation: art therapy, physical training, or occupational therapies | Significant differences between groups in CGI-S (IPT-Cog: −0.96 ± 0.72, ES = −80; Cogpack: −0.80 ± 0.76, ES = −0.57; rehabilitation: −0.36 ± 0.78, p = 0.02) Significant differences between groups for PANSS positive scores (IPT-Cog: 5.0 ± 3.40; ES = −0.83; Cogpack: −5.47 ± 4.92; ES = −0.79; rehabilitation: −1.79 ± 4.33, p< 0.001) Significant differences between groups for PANSS negative scores (IPT-Cog: −6.96 ± 5.6, ES = −1.29; Cogpack: −4.90 ± 6.31, ES = −0.94; rehabilitation: 0.04 ± 4.13, p < 0.001); significant differences between groups for PANSS total scores (IPT-Cog: −21.65 ± 15.40, ES = −1.19; Cogpack: −20.80 ± 18.35, ES = −1.03; rehabilitation: −3.71 ± 14.68, p < 0.001) | Low |

| Zhu et al., 2022 [17] | China | N = 270, 144/72/54 CCRT 46.60 ± 8.94 CRT 47.56 ± 8.23 Active control 46.11 ± 8.21 63.7% | Computerized cognitive remediation therapy; cognitive remediation therapy | 45 min/session, 4–5 sessions/w, 12 weeks, 50 sessions | Cognitive flexibility, working memory and planning, facial emotion recognition, context emotion estimation, and emotional management | Active control: dance learning, playing a simple instrument | No significant effects on PANSS scores | Low |

| Zhu et al., 2020 [23] | China | N = 157, 78/79 CCRT 43.74 (9.24) Treatment as Usual 43.65 (8.64) 54.1% Community-dwelling, clinically stable | Computerized cognitive remediation therapy | 45 min/session, 4–5 sessions/w, 12 weeks | Cognitive flexibility, working memory, planning, social functions, i.e., emotion management | Treatment as Usual (medication) | No significant effects on PANSS scores | Moderate |

| Tan et al., 2016 [18] | China | N = 90, 44/46 CRT: 46.77 ± 7.18 MDT: 46.09 ± 5.52 60% Inpatients, chronic | Group cognitive remediation therapy, Frontal/Executive Function Program (Revised) (Chinese) | 1 h/session, 4 sessions/w, 10 weeks, 40 sessions | Flexibility in thinking and information set maintenance, working memory, goal-oriented, set/schema formation, manipulation, and planning | Musical and Dancing Therapy (MDT) | No significant effect on PANSS scores | Low |

| D’Amato et al., 2011 [44] | France | N = 77, 39/38 Intervention 33.4 ± 6.9 Control 32.2 ± 6.0 75.3% Outpatients, remitted | Cognitive remediation therapy, Rehacom | 2 h/session, 2 sessions/w, 7 weeks, 14 sessions | Attention/ concentration, working memory, logic, and executive functions | Treatment as Usual, waiting list | No significant effect on PANSS, CGI scores | High |

| Ricarte et al., 2012 [33] | Spain | N = 50, 24/26 Active 38.34 ± 9.6 Control 35.21 ± 13.3 82% Inpatients, outpatients | Event-Specific Memory Training | 90 min/session, 1 session/w, 10 weeks | Autobiographical memory | Social skills and occupational therapy | Significant differences between groups for BDI scores (experiment: 18.25 ± 12.3 → 10.16 ± 8.4; control: 12.42 ± 10.2 → 11.92 ± 11.0, p = 0.006, ηp2 =0.15) | Moderate |

| Omiya et al., 2016 [20] | Japan | N = 17, 8/9 Fep 43.25 ± 14.50 Control 39.00 ± 11.09 41.1% Inpatients, outpatients, chronic | Frontal/Executive Program | 60 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 24 weeks, 44 sessions | Cognitive flexibility, working memory, planning | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant differences for PANSS total scores (FEP: 79.9 ± 7.9 → 68 ± 10.2; control 77.4 ± 6.2 → 78.1 ± 7.59, p < 0.03) | Low |

| Wykes et al., 2007 [24] | U.K. | N = 40, 21/19 CRT 18.8 (2.6) Control 17.5 (2.2) 65% inpatients at follow-up | Cognitive remediation therapy | 1 h/session, 3 sessions/w, 12 weeks | Memory, cognitive flexibility, planning | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | No significant effect on SPRS | Moderate |

| Rakitzi et al., 2016 [25] | N = 48, 24/24 IPT 31.3 ± 7.2 Control 33.8 ± 6.7 66% Outpatients | Integrated Psychological Therapy (IPT) – Group Therapy Cognitive Component | 1 h/session, 2 sessions/w, 10 weeks, 20 sessions | Vigilance/attention, working memory, verbal memory, social perception | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological) | Significant differences between groups for PANSS negative scores (IPT: 33.5 ± 4.5 → 26.1 ± 4.3 → 24.0 ± 4.6; control: 31.0 ± 4.3 → 30.3 ± 5.8 → 28.9 ± 4.7; T1–T2: p = 0.00 d = 0.89; T1–T3: p = 0.00 d = 1.12); significant differences between groups for PANSS total scores (IPT: 59.9 ± 14.3 → 45.6 ± 9.4 → 43.9 ± 13.8; control: 59.0 ± 12.6 → 55.5 ± 9.9 → 52.2 ± 13.0; T1–T3: p = 0.01, d = 0.75) | Moderate | |

| Wykes et al., 2003 [26] | U.K. | N = 33, 17/16 CRT 36.5 (19–55) Control 40.6 (24–64) 75% Outpatients | Cognitive remediation therapy | 12 weeks | Flexibility, memory, planning | Intensive occupational therapy activities | No significant effect on BPRS scores | Moderate |

| Sachs et al., 2012 [34] | Austria | N = 38, 20/18 TAR 27.20 ± 7.17 Treatment as Usual 31.72 ± 9.35 52.6% Inpatients, outpatients | Training of Affect Recognition (TAR) | 2 sessions/w, 6 weeks, 12 sessions | Facial affect recognition | Treatment as Usual, occupational therapy | Significant within-group differences for PANSS negative scores (TAR: 27.35 ± 7.72 → 18.45 ± 6.18, p < 0.001 d = 1.27); significant interaction between group and time (F(1,36) = 12.671, p = 0.001); significant within-group differences for BDI scores (TAR 13.00 ± 9.82 → 8.25 ± 8.16. d = 0.53, p = 0.001) | High |

| Giuliani et al., 2024 [45] | Italy | N = 40, 20/20 Intervention 37.15 ± 9.96 Control 36.70 ± 9.44 70% Outpatients | Modified Social Cognition Individualized Activities Lab (mSoCIAL) | 30 min/session, 1 session/w, 10 weeks | Social cognition and metacognitive skills, emotion recognition, Theory of Mind, narrative enhancement | Treatment as Usual (pharmacological, psychological, rehabilitative, occupational) | No significant effect on PANSS scores | High |

| Li et al., 2022 [35] | China | N = 62, 30/32 VRT 46 (37, 50) Control 47.5 (37.25, 51.75) Gender Males 62.9% Inpatients, remitted | Virtual reality (VR) | 5 sessions/w, 2 weeks | Working memory, processing speed, attention, verbal memory, visual memory, reasoning problem solving, social cognition | Treatment as Usual (antipsychotic treatment) | Significant pre and post differences for PANSS general scores (VR: 19 (18, 23) vs. 17 (16, 21)); Treatment as Usual 19 (17.5, 21) vs. 19 (17.25, 20.75), p = 0.016, ES = 0.458 Significant difference for volition scores, VR < Treatment as Usual, p = 0.014 | Moderate |

| Fathi et al., 2025 [19] | Iran | N = 54, 27/27 CCT41.78 ± 5.22 Control 40.67 ± 8.04 61% | Computerized Cognitive Training (CCT)-CANTAB | 1 h/session, 3 sessions/w, 10 weeks | Spatial Recognition Memory (SRM), Paired Associate Learning (PAL), Spatial Working Memory (SWM), Spatial Planning and Spatial Span (SSP) | Active control: computer games with high cognitive demands | Significant main effects of time and time × group interaction on DASS-D scores (CCT: MD = −1.85, 95% CI [−1.90, 0.42], p = 0.005); significant time × group interaction for DASS-S scores within the CCT group; T1 and T2 were significantly higher than T0 (MD (95% CI) = 2.96 (1.54 to 4.38), p < 0.001; MD = 2.67, 95% CI [1.18, 4.16], p < 0.001); significant difference between the two groups at both T1 and T2 (MD = 2.15, 95% CI [0.69, 3.61], p < 0.001; MD = −1.93, 95% CI [3.27, −0.59], p < 0.001); significant difference between the intervention and control groups (MD (95% CI) = 4.30 (1.38 to 7.22), p < 0.001), with the positive effects of the intervention persisting up to 3 months post-intervention (MD (95% CI) = −3.70 (−6.54 to −1.18), p = 0.001) | Low |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [46] | China | N = 40, 20/20 CCRT 48.200 ± 2.114 Control 46.850 ± 2.048 100% Inpatients, institutionalized | Computerized cognitive remediation therapy | 40 min/session, 5 sessions/w, 8 weeks | Attention, working memory, speed of processing, cognitive flexibility, reasoning and problem solving, social cognition | Treatment as Usual (medication only) | Significant time × group interaction for PANSS total scores (CCRT: 77.30 ± 2.68 vs. 75.90 ± 2.72 vs. 74.90 ± 2.85; control: 80.90 ± 2.11 vs. 80.90 ± 2.11 vs. 80.90 ± 2.11, p < 0.001); significant within-group differences for PANSS negative scores (CCRT: 27.00 ± 1.21 vs. 26.15 ± 1.21 vs. 25.65 ± 1.24; control: 27.40 ± 1.27 vs. 27.40 ± 1.27 vs. 27.40 ± 1.27, p < 0.001); significant time × group interaction for HDRS (CCRT: 5.25 ± 0.68 vs. 3.20 ± 0.56 vs. 2.75 ± 0.43; control: 4.10 ± 0.56 vs. 3.35 ± 0.64 vs. 4.40 ± 0.91, p < 0.015) | High |

| Dai et al., 2022 [27] | China | N = 82, 25/26/31 CAE 41.50 (8.72) Aerobic 41.40 (7.86) Control 44.06 (8.40) 75.6% Inpatients, remitted | Computerized cognitive remediation therapy; CCRT + aerobic exercise = CAE | 30 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 8 weeks | Processing speed, cognitive flexibility | Aerobic, Treatment as Usual (antipsychotics, psychological consultation, medical care, and behavior modification) | Significant pre and post differences for PANSS negative scores (CAE: −2.69 (1.83); AE: −1.48 (2.22), control: −1.06 (2.37), CAE vs. control: p = 0.018 ES = 0.096) | Moderate |

| Fekete et al., 2022 [36] | Hungary | N = 46, 23/23 MCT 44.22 ± 10.45 Control 38.39 ± 10.41 47.8% Outpatients | Group Metacognitive Training (MCT) | 1 session/w, 16 weeks | Mental flexibility, jumping to conclusions, emotion recognition, Theory Of Mind, metacognitive functioning, attributional style | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy, regular psychiatric control and care) | PANSS between groups post intervention positive, b = −4.66, p = 0.045, disorganized b = −5.98, p = 0.018, total b = −14.34, p = 0.026; between groups, post vs. 6 months positive b = −4.78 p = 0.046, disorganized b = −6.89 p = 0.022, total b = −14.95, p = 0.033 Within-group, mct post vs. baseline positive total b = −10.44, p = 0.029, negative b = −3.84, p = 0.048, disorganized b = −4.57 p = 0.007, post vs. 6 months no difference Control: no difference Baseline PANSS scores (≥75 PANSS total score or <75 PANSS, greater improvement) T0–T1 B = −21.8 p < 0.001 T0–T2 B = −16.9, p = 0.046 | Moderate |

| Sampedro et al., 2021 [28] | Spain | N = 94, 47/47 Rehacop 40.60 ± 10.45 Control 41.43 ± 10.41 83% Inpatients, outpatients, rehabilitation unit | Rehacop + psychoeducation | 60 min/session, 3 sessions/w, 20 weeks | Attention, visual and verbal learning, recall, recognition memory, working memory; language: verbal comprehension, verbal fluency, and abstract language; executive functions planning, problem solving, cognitive flexibility, reasoning, categorization and conceptualization, processing speed, social cognition emotion | Active control, occupational group activities (gardening, sewing, handicrafts, painting, and music), psychoeducation | Significant pre and post differences for negative scores (Rehacop: 6.83 [−9.18, −4.58]; control: −1.60 [−3.60, −0.12], p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.108) Disorganization Rehacop: −0.97 [−1.48, −0.49]; control: −0.13 [−0.47, −0.25], p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.086 Excitement Rehacop: −1.20 [−1.74, −0.65]; control: −0.24 [−0.98, −0.49], p = 0.041, ηp2 = 0.049 | Moderate |

| Rocha et al., 2021 [21] | Portugal | N = 11, 6/5 SCIT 29.5 ± 13.38 Control 27 ± 6.12 90.9% Outpatients, illness duration <2 years | Group Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) | 45–60 min/ session, 1 session/w, 20 sessions | Theory of Mind, emotion perception, attributional bias | Psychoeducation | No significant effect on PSP or PANSS scores | Moderate |

| Bossert et al., 2020 [37] | Germany | N = 59, 19/18/21 I-CACR 32.37 ± 8.71 G-CACR 28.68 ± 9.43 Treatment as Usual 29.67 ± 6.65 72.8% Inpatients, outpatients | Group Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation CogniPlus (I-CACR); Individualized Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation (I-CACR) | 50 min/session, 4 sessions/w, 5 weeks | Attention: alertness, selective, divided; working memory, executive functions | Treatment as Usual (pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment, occupational therapy, and social skill training) | No significant effect on PANSS or HAMD scores, except for self-reported depression (BDI-scores), where a main effect of time was revealed: F(1, 52) = 22.82, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.31 for the total sample | Moderate |

| Matsuda et al., 2018 [29] | Japan | N = 62, 31/31 Outpatients | Japanese Cognitive Rehabilitation Program for Schizophrenia (JCORES) | 60 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 12 weeks | Attention, psychomotor speed, learning, memory, executive functions | Treatment as Usual, waiting list | Significant differences between groups for PANSS on PANSS general subscales (JCORES: −3.17 ± 4.33; control: −0.06 ± 5.93, p = 0.032) | Moderate |

| Peña et al., 2016 [30] | Spain | N = 101, 52/49 Inpatients, outpatients | Rehacop Social Cognitive Intervention and Functional Skills Training | 90 min/session, 3 sessions/w, 16 weeks | Attention: sustained, selective, alternating, divided; memory: visual and verbal learning, recall, recognition; language: verbal fluency, verbal comprehension, abstract language; executive functions: planning, social cognition | Occupational group activities | Significant effect on PANSS negative scores (Rehacop: −5.29 [−6.45, −4.13]; control: −2.82 [−4.01, −1.62] p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.082) Emotional distress (Rehacop: −2.68 [−3.33, −2.02]; control: −0.81 [−1.49, −0.14], p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.136); negative subfactor (Rehacop −5.29 [−6.45, −4.13]; control: −2.82 [−4.01, −1.62], ES = 0.082); differences for negative subdomains: social amotivation, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.077 | Moderate |

| Cella et al., 2014 [38] | U.K. | N = 85 Community mental health teams | Cognitive rehabilitation | 3 sessions/w, 40 sessions | Executive functions, working memory, long-term memory, attention | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant reduction of negative symptoms and disorganization in the CR group: W_Neg, F(2, 80) = 21.1, p < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.07, and W_Dis, F(2, 80) = 14.2, p < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.1 | Moderate |

| Klingberg et al., 2011 [14] | Germany | 198 36.9 ± 9.9 56.1% | Cognitive rehabilitation, restitution, compensation of cognitive deficits | 47.5 min/session (mean), 13.7 sessions | Attention, memory, executive functions | CBT | No significant effect on PANSS, SANS, CDSS, or CGI scores | Low |

| Kayser et al., 2006 [31] | France | 14 Video: 32.4 ± 9.4 Control: 38.2 ± 9.2 50% | Theory of Mind Training using videos depicting emotional interactions | 1 session/w, 12 weeks | Theory of Mind | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | No significant effects on PANSS and BPRS scores | High |

| Reeder et al., 2004 [32] | U.K. | 31 31.3 ± 13.5 16–64 73% | Cognitive rehabilitation training | 3 sessions/w, 40 sessions | Attention, memory; executive functions: cognitive shift, working memory, planning | Occupational therapy, activities to account for therapist contact | No significant effects on BPRS scores | High |

| Beigi et al., 2008 [42] | Iran | 42 Unclear Unclear | Cognitive rehabilitation therapy | 30–45 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 8 weeks | Attention, memory, executive function, abstract thinking | Treatment as Usual (pharmacological therapy) | Significant differences between groups for SAPS scores (CRT: 66.15 ± 13.98 → 53.75 ± 12.32, TAU: 66.85 ± 15.21 → 66.35 ± 17.71, p < 0.001); significant differences between groups for SANS scores (CRT: 59.35 ± 13.05 → 54.1 ± 12.37; TAU: 63.15 ± 10.29 → 63.85 ± 10.83, p < 0.05) | High |

| Tao et al., 2015 [47] | China | 86 CR: 28.95 ± 7.38 Control: 29.71 ± 6.36 54.6% | Cognitive rehabilitation | 30 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 16 weeks | Memory, attention, language, executive functions, coordination | Treatment as Usual, pharmacological | No significant effects on PANSS scores | |

| Yamanushi et al., 2024 [39] | Japan | 15/15 | Cognitive remediation therapy, Rehacom | 60 min/session, 2 sessions/w, 12 weeks, 24 sessions | Attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant time × group interaction for (SANS) anhedonia/asociality scores (Rehacom: 21.57 ± 4.16 → 18.36 ± 4.80; control: 21.69 ± 3.84 → 21.23 ± 3.30, p = 0.019, ES = 0.19); no significant effect on the PANSS and other subscales | Moderate |

| Ojeda et al., 2012 [48] | Spain | 93 33.81± 9.7/37.75± 8.3 81.1% | Rehacop | 90 min/session, 3 sessions/w, 12 weeks | Attention, processing speed, memory, language, executive functions, social cognition | Occupational therapy | Significant difference between groups when controlling cognitive change in insight and CGI scores improved (Rehacop-insight: 5.46 ± 3.5 → 7.92 ± 3.1; control: 8.50 ± 4.4 → 8.64 ± 4.2) (Rehacop-CGI: 5.12 ± 1.3 → 4.12 ± 1.3; control CGI: 4.63 ± 1.3 → 3.94 ± 1.5) | High |

| Sánchez et al., 2014 [40] | Spain | N = 92, 36/48 Rehacop: 33.60 ± 9.4 Control: 36.92 + 10.5 69.5% | Rehacop | 90 min/session, 3 sessions/w, 12 weeks | Attention, memory, processing speed, language, executive functions, social cognition | Treatment as Usual (psychopharmacological therapy) | Significant time × group interaction between groups for negative symptoms (Rehacop: 27.23 ± 11.6 → 21.91 ± 9.4; control: 24.85 ± 9.7 → 22.84 ± 10.1, ES = 0.48); significant time × group interaction for disorganization scores (Rehacop: 17.03 ± 7.2 → 12.91 ± 5.6; control 14.13 ± 5.4 → 12.67 → 6.1, ES = 0.58) Significant time × group interaction for emotional distress (Rehacop: 10.97 ± 6.2 → 7.66 ± 3.9; control: 7.95 ± 4.7 → 6.33 ± 3.5, ES = 0.47); significant differences for PANSS total scores (Rehacop: 99.39 ± 34.8 → 74.83 ± 23.5; control: 84.56 ± 25.1 → 71.70 ± 25.6, ES = −0.50) | Moderate |

On the contrary, statistically significant improvements in negative symptoms were more readily found and are reported by 12 studies. Of those, five report effect sizes, large [25,27,28] or medium to large [30,38], in samples including outpatients, remitted inpatients, or both. Specifically, Peña et al. and Yamanushi et al. reported improvements in social amotivation and anhedonia/asociality with medium to large effect sizes [30,39]. Duration of studies was between 6 and 24 weeks.

Five studies also report significant superiority of cognitive remediation interventions vs. control conditions on the general PANSS subscale, with small, medium, or large effect sizes [25,29,35,41,46], and another five for total PANSS scores [16,20,36,41,46]. In the study by Penadés et al. [15], which compared cognitive remediation vs. CBT in a sample of chronic outpatients, CBT outperformed cognitive remediation in the general PANSS subscale, while CR was superior in the cognitive factor of PANSS. Positive results are also reported for disorganization [28,36,38,40], with large sizes [28], for excitement, with medium sizes [30,40], and for emotional distress, with a large effect size. Fekete et al. investigated whether baseline symptom severity had any impact on the degree of symptomatic improvement; they found that a PANSS score of >75 was predictive of greater improvements of symptoms following cognitive rehabilitation [36].

Insight was explored by Ojeda et al. [48], where a significantly superior effect over occupational therapy was reported. Volition was found to respond better to CR vs. TAU, according to Li et al. [35].

Nine studies focused on other symptoms of schizophrenia. Regarding depression, significantly superior results were reported by five studies [19,33,34,37,46], with a small to moderate effect size. Two studies yielded negative outcomes [14,43]. In the study by Penadés et al. [15], CBT proved superior to CR for the treatment of depressive symptoms. As for anxiety, the study by Fathi et al. [19] found better performance of CR on the stress subscale of DASS (DASS-S], but not anxiety. Also, Gharaeipour and Scott [43] obtained negative results regarding anxiety.

Only two studies reported long-term follow-up assessments at 3 or 6 months and showed that therapeutic effects seem to persist [19,36].

4. Discussion

Although cognitive remediation has well-documented effects on cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia, results for other symptoms seem promising, yet not unequivocally. In the present review, the existing evidence is mixed, with positive and negative results for various aspects of psychopathology. There are several reasons that could lead to this inconsistency. A significant portion of the studies included in the present systematic review had one or multiple methodological issues. Information regarding blinding, group allocation, or inter–rater reliability was often omitted from the studies. Furthermore, the exclusion of articles in other languages instead of English could have excluded relevant findings. Patient samples are mostly rather small, and studies present significant heterogeneity in terms of setting, including inpatient, outpatient in the community or in rehabilitation, and day centers, phase of illness, whether acute, chronic, remitted, or early course, type and components of intervention, dosing, including number of sessions and duration of treatment, and control conditions, including Treatment as Usual or treatments other than cognitive remediation. Although a meta-analysis could possibly clarify or reduce the confusion, the degree of heterogeneity would compromise the comparability of the studies and the feasibility of meta-analytic processing. It is expected that effects on patients with different characteristics would vary. It is probable that in situations where positive symptoms are severe, there is a larger deviation of scale scores than in a remitted condition and a larger range for putative improvement, which is more promptly demonstrable by the statistical analyses. This could be the case for the positive results of the studies on acutely ill patients, contrary to most studies, which yield negative results. In stable subjects, on the other hand, marked negative symptoms with minimal scores on positive subscales are the most common presentation; hence, it is for negative symptoms that patients would experience more benefits. In the same line stand the findings of Fekete et al. [36], where total scores of PANSS > 75 are associated with significantly greater improvements from the intervention. Given that a large percentage of patients are only partially remitted or refractory despite adequate trials of antipsychotic medication, the therapeutic potential of cognitive remediation becomes particularly important.

Although the effectiveness of the intervention cannot be definitively ascertained at this point, given that effect sizes of the improvements were in many cases large or medium and follow-up assessments demonstrated maintenance of the therapeutic benefits, this is very important for the substantiation of the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation methods. Furthermore, investigation of the neurobiological processes that underly the therapeutic effects and mediate the transfer of the cognitive gains to other areas of clinical state and functioning remains crucial. Some studies have investigated neurobiological and neuroimaging aspects of cognitive rehabilitation that could be relevant to this matter. Increased activation and functional connectivity after cognitive remediation have been reported in multiple regions, such as the prefrontal cortex and thalamic regions [49,50]. Sampedro et al. [51], based on the sample of patients they examined in their previous study [28] (which is included in the present review), found greater cortical thickness in the right temporal lobe (right temporal pole, inferior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus) at post-treatment compared to pre-treatment in the REHACOP group but not in the active control group. These are areas especially pertinent to the pathophysiology of positive and negative schizophrenic symptoms. More specifically, dysfunction in temporal areas has been associated with auditory hallucinations and disruption of fronto-striato-thalamic circuits with delusions [52,53]. Negative symptoms are thought to be related to the hypofunction of frontal areas, including the anterior cingulate cortex [54]. Frontal lobe dysfunction has been identified as a neural correlate of depression [55]. Furthermore, enhanced self-esteem is related to the newly achieved functional gains, which adds to the patients’ positive affect [56].

A groundbreaking line of research focuses on the glymphatic system’s function in relation to psychosis. This system is a pathway based on the astrocytes, and it allows for the exchange of cerebrospinal fluid with interstitial fluid through a paravascular network formed by the astrocytes, with aquaporin-4 (AQP4) having a central role. Normally, this leads to the removal of solute metabolic waste from the cerebrospinal fluid to the lymphatic system and thus to a clean and stable brain microenvironment [57,58]. Intact sleep, particularly delta-rich slow-wave (N3) sleep, is crucial for optimal system function [59].

It has been recently indicated that people with psychosis, even at an early stage of illness, show compromised function of the glymphatic system compared to healthy controls [60], and such a dysfunction is correlated with cognitive impairment [61] and psychotic symptoms [62].

Could this action work both ways? More specifically, could the amelioration of cognitive functioning through cognitive remediation help normalize glymphatic function? Although currently this is just a hypothesis, there are some supporting recent findings. Enhanced cognitive function seems to improve resting-state functional connectivity [63] and relieve sleep problems [64], which could result in enhancing glymphatic system function. This, in turn, would allow for more efficient removal of metabolic waste, a stable brain microenvironment, and improvement of the status of neuroglia and astrocytes, with further empowerment of large-scale brain circuits. Because of these changes, psychotic and cognitive symptoms might be further reduced, establishing a virtuous circle of clinical improvement.

In view of the above, many issues remain to be elucidated. The preceding neurobiological explanation of the therapeutic effects of cognitive remediation, although aligned with current knowledge on brain function, remains only hypothetical and fragmentary, calling for robust, extensive research. Questions regarding optimal elements of the intervention and the duration, dosing, and timing of the therapy must be answered. Documentation of the cost-effectiveness of the method is another critical issue that would facilitate the broader delivery of cognitive rehabilitation. To this end, there is a need for more studies with low risk of bias and larger samples of patients. Standardized outcome measures and long-term follow-up would further strengthen evidence around the effectiveness and the persistence of the therapeutic effects. The present data indicate that a careful recommendation of this intervention can be offered alongside treatment as usual while awaiting more definitive data.

5. Limitations

Limitations of the present study include the fact that the literature search was conducted using three databases only. This might have led to the omission of studies available through other databases, such as Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and others. If included, they might contribute to findings that would enrich our results and further increase the robustness of the present study. The same limitation pertains to the exclusion of articles written in languages other than English. Articles published in languages other than English were not included, and therefore certain information may be missed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci15101130/s1. Refs. [65,66,67,68,69,70] are cited in the Supplementary Materials file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and L.M.; methodology, M.S. and P.-D.S.; validation, M.S. and L.M.; formal analysis, M.S. and P.-D.S.; investigation, M.S. and P.-D.S.; resources, P.-D.S. and A.N.-M.; data curation, A.N.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., P.-D.S., and A.N.-M.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and L.M.; visualization, P.-D.S.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CR | Cognitive remediation |

References

- Jauhar, S.; Johnstone, M.; McKenna, P.J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2022, 399, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Priller, J.; Davis, J.M. Antipsychotic Drugs: A Concise Review of History, Classification, Indications, Mechanism, Efficacy, Side Effects, Dosing, and Clinical Application. Am. J. Psychiatry 2024, 181, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, A.; Barlati, S. Recovery from Schizophrenia: Is It Possible? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2018, 31, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Umehara, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nakataki, M.; Numata, S. Schizophrenia and Cognitive Dysfunction. J. Med. Investig. 2024, 71, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziwota, E.; Stepulak, M.Z.; Włoszczak-Szubzda, A.; Olajossy, M. Social Functioning and the Quality of Life of Patients Diagnosed with Schizophrenia. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2018, 25, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javitt, D.C. Cognitive Impairment Associated with Schizophrenia: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 63, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, T.; Greeshma, M. Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2012, 24, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, E.; Fonseca, L.; Rocha, D.; Trevizol, A.; Cerqueira, R.; Ortiz, B.; Brunoni, A.; Bressan, R.; Correll, C.; Gadelha, A. Treatment Resistance in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Correlates. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2023, 45, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokou, M.; Messinis, L.; Nasios, G.; Gourzis, P.; Dardiotis, E. Cognitive Rehabilitation for Patients with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review of Moderating Factors, Strategies, and Outcomes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1423, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, A.; Gaebel, W.; Mucci, A.; Sachs, G.; Barlati, S.; Giordano, G.M.; Nibbio, G.; Nordentoft, M.; Wykes, T.; Galderisi, S. European Psychiatric Association Guidance on Treatment of Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2022, 65, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, C.; McIntosh, E.J.; Unger, S.; Haddaway, N.R.; Kecke, S.; Schiemann, J.; Wilhelm, R. Online Tools Supporting the Conduct and Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Systematic Maps: A Case Study on CADIMA and Review of Existing Tools. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Stone, J.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingberg, S.; Wölwer, W.; Engel, C.; Wittorf, A.; Herrlich, J.; Meisner, C.; Buchkremer, G.; Wiedemann, G. Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia as Primary Target of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Results of the Randomized Clinical TONES Study. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37 (Suppl. 2), S98–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penadés, R.; Catalán, R.; Salamero, M.; Boget, T.; Puig, O.; Guarch, J.; Gastó, C. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Outpatients with Chronic Schizophrenia: A Controlled and Randomized Study. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 87, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.; De Peri, L.; Barlati, S.; Cacciani, P.; Deste, G.; Poli, R.; Agrimi, E.; Cesana, B.M.; Sacchetti, E. Effectiveness of Different Modalities of Cognitive Remediation on Symptomatological, Neuropsychological, and Functional Outcome Domains in Schizophrenia: A Prospective Study in a Real-World Setting. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 133, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Fan, H.; Zou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, F.; Reeder, C.; Zhou, D.; et al. Computerized or Manual? Long Term Effects of Cognitive Remediation on Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 239, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zou, Y.; Wykes, T.; Reeder, C.; Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhou, D. Group Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Chronic Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 626, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi Azar, E.; Mirzaie, H.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Haghgoo, H.A. Acceptability and Impact of Computerised Cognitive Training on Mental Health and Cognitive Skills in Schizophrenia: A Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Gen. Psychiatry 2025, 38, e101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omiya, H.; Yamashita, K.; Miyata, T.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Miyajima, M.; Yambe, K.; Matsumoto, I.; Matsui, M.; Toyomaki, A.; Denda, K. Pilot Study of the Effects of Cognitive Remediation Therapy Using the Frontal/Executive Program for Treating Chronic Schizophrenia. Open Psychol. J. 2016, 9, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rocha, N.B.; Campos, C.; Figueiredo, J.M.; Saraiva, S.; Almeida, C.; Moreira, C.; Pereira, G.; Telles-Correia, D.; Roberts, D. Social Cognition and Interaction Training for Recent-Onset Schizophrenia: A Preliminary Randomized Trial. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Song, H.; Chang, R.; Chen, B.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, K. Combining Compensatory Cognitive Training and Medication Self-Management Skills Training, in Inpatients with Schizophrenia: A Three-Arm Parallel, Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 69, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Fan, H.; Fan, F.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Xue, F.; Xiao, C.; Li, W.; et al. Improving Social Functioning in Community-Dwelling Patients with Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Computer Cognitive Remediation Therapy Trial with Six Months Follow-Up. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykes, T.; Newton, E.; Landau, S.; Rice, C.; Thompson, N.; Frangou, S. Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) for Young Early Onset Patients with Schizophrenia: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 94, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitzi, S.; Georgila, P.; Efthimiou, K.; Mueller, D.R. Efficacy and Feasibility of the Integrated Psychological Therapy for Outpatients with Schizophrenia in Greece: Final Results of a RCT. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 242, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wykes, T.; Reeder, C.; Williams, C.; Corner, J.; Rice, C.; Everitt, B. Are the Effects of Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) Durable? Results from an Exploratory Trial in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2003, 61, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ding, H.; Lu, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, C.; Jiang, T.; Ming, L.; Xia, Z.; Song, C.; Shen, H.; et al. CCRT and Aerobic Exercise: A Randomised Controlled Study of Processing Speed, Cognitive Flexibility, and Serum BDNF Expression in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Heidelb. Ger. 2022, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampedro, A.; Peña, J.; Sánchez, P.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Gómez-Gastiasoro, A.; Iriarte-Yoller, N.; Pavón, C.; Tous-Espelosin, M.; Ojeda, N. Cognitive, Creative, Functional, and Clinical Symptom Improvements in Schizophrenia after an Integrative Cognitive Remediation Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial. NPJ Schizophr. 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, Y.; Morimoto, T.; Furukawa, S.; Sato, S.; Hatsuse, N.; Iwata, K.; Kimura, M.; Kishimoto, T.; Ikebuchi, E. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Cognitive Remediation Programme with Original Computerised Cognitive Training and Group Intervention for Schizophrenia: A Multicentre Randomised Trial. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2018, 28, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Sánchez, P.; Iriarte, M.B.; Elizagarate, E.; Garay, M.A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Iribarren, A.; Ojeda, N. Combining Social Cognitive Treatment, Cognitive Remediation, and Functional Skills Training in Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. NPJ Schizophr. 2016, 2, 16037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, N.; Sarfati, Y.; Besche, C.; Hardy-Baylé, M.-C. Elaboration of a Rehabilitation Method Based on a Pathogenetic Hypothesis of “Theory of Mind” Impairment in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2006, 16, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, C.; Newton, E.; Frangou, S.; Wykes, T. Which Executive Skills Should We Target to Affect Social Functioning and Symptom Change? A Study of a Cognitive Remediation Therapy Program. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricarte, J.J.; Hernández-Viadel, J.V.; Latorre, J.M.; Ros, L. Effects of Event-Specific Memory Training on Autobiographical Memory Retrieval and Depressive Symptoms in Schizophrenic Patients. Autobiographical Mem. Psychopathol. 2012, 43, S12–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, G.; Winklbaur, B.; Jagsch, R.; Lasser, I.; Kryspin-Exner, I.; Frommann, N.; Wölwer, W. Training of Affect Recognition (TAR) in Schizophrenia—Impact on Functional Outcome. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 138, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, R.; Sun, B.; Wei, N.; Shen, Z.; Xu, Y.; Huang, M. Effect of Virtual Reality on Cognitive Impairment and Clinical Symptoms among Patients with Schizophrenia in the Remission Stage: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, Z.; Vass, E.; Balajthy, R.; Tana, Ü.; Nagy, A.C.; Oláh, B.; Domján, N.; Kuritárné, I.S. Efficacy of Metacognitive Training on Symptom Severity, Neurocognition and Social Cognition in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossert, M.; Westermann, C.; Schilling, T.M.; Weisbrod, M.; Roesch-Ely, D.; Aschenbrenner, S. Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation in Schizophrenia: Efficacy of an Individualized vs. Generic Exercise Plan. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 555052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, M.; Reeder, C.; Wykes, T. It Is All in the Factors: Effects of Cognitive Remediation on Symptom Dimensions. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 156, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanushi, A.; Shimada, T.; Koizumi, A.; Kobayashi, M. Effect of Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation Therapy on Cognition among Patients with Schizophrenia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, P.; Peña, J.; Bengoetxea, E.; Ojeda, N.; Elizagárate, E.; Ezcurra, J.; Gutiérrez, M. Improvements in Negative Symptoms and Functional Outcome after a New Generation Cognitive Remediation Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, A.; De Peri, L.; Barlati, S.; Cacciani, P.; Cisima, M.; Deste, G.; Cesana, B.M.; Sacchetti, E. Psychopathologic, Neuropsychological and Functional Outcome Measures during Cognitive Rehabilitation in Schizophrenia: A Prospective Controlled Study in a Real-World Setting. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, N.A.; Mohamadkhani, P.; Mazinani, R.; Dolatshahi, B. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Group Cognitive- Rehabilitation Therapy for Patients with Schizophrenia Resistant to Medication. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2008, 6, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gharaeipour, M.; Scott, B. Effects of Cognitive Remediation on Neurocognitive Functions and Psychiatric Symptoms in Schizophrenia Inpatients. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 142, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Amato, T.; Bation, R.; Cochet, A.; Jalenques, I.; Galland, F.; Giraud-Baro, E.; Pacaud-Troncin, M.; Augier-Astolfi, F.; Llorca, P.-M.; Saoud, M.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 125, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, L.; Pezzella, P.; Mucci, A.; Palumbo, D.; Caporusso, E.; Piegari, G.; Giordano, G.M.; Blasio, P.; Mencacci, C.; Torriero, S.; et al. Effectiveness of a Social Cognition Remediation Intervention for Patients with Schizophrenia: A Randomized-Controlled Study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 23, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Qin, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhu, H.; Hu, W.; He, X.; Tang, K.; Yan, Q.; Shen, H. Enhanced Computerized Cognitive Remediation Therapy Improved Cognitive Function, Negative Symptoms, and GDNF in Male Long-Term Inpatients with Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1477285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zeng, Q.; Liang, J.; Zhou, A.; Yin, X.; Xu, A. Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation Training on Schizophrenia: 2 Years of Follow-Up. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 16089–16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, N.; Peña, J.; Bengoetxea, E.; Garcia, A.; Sánchez, P.; Elizagárate, E.; Segarra, R.; Ezcurra, J.; Gutiérrez-Fraile, M.; Eguíluz, J.I. Evidence of the Effectiveness of Cognitive Rehabilitation in Psychosis and Schizophrenia with the REHACOP Programme. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 54, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mothersill, D.; Donohoe, G. Neural Effects of Cognitive Training in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Activation Likelihood Estimation Meta-Analysis. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2019, 4, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penadés, R.; Pujol, N.; Catalán, R.; Massana, G.; Rametti, G.; García-Rizo, C.; Bargalló, N.; Gastó, C.; Bernardo, M.; Junqué, C. Brain Effects of Cognitive Remediation Therapy in Schizophrenia: A Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Study. Schizophr. Context Mem. 2013, 73, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, A.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Peña, J.; Cabrera-Zubizarreta, A.; Sánchez, P.; Gómez-Gastiasoro, A.; Iriarte-Yoller, N.; Pavón, C.; Tous-Espelosin, M.; Ojeda, N. Analyzing Structural and Functional Brain Changes Related to an Integrative Cognitive Remediation Program for Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Schizophr. Res. 2023, 255, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvsannyam, E.; Jain, M.S.; Pormento, M.K.L.; Siddiqui, H.; Balagtas, A.R.A.; Emuze, B.O.; Poprawski, T. Neurobiology of Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e23959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.W.; Tang, W.H. Hallucinations: Diagnosis, Neurobiology and Clinical Management. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galderisi, S.; Merlotti, E.; Mucci, A. Neurobiological Background of Negative Symptoms. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 265, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, G.M. Neuropsychological and Neuroimaging Evidence for the Involvement of the Frontal Lobes in Depression: 20 Years On. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1090–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, G.; Barrios, M.; Penadés, R.; Enríquez, M.; Garolera, M.; Aragay, N.; Pajares, M.; Vallès, V.; Delgado, L.; Alberni, J.; et al. Computer-Assisted Cognitive Remediation Therapy: Cognition, Self-Esteem and Quality of Life in Schizophrenia. Spec. Sect. Negat. Symptoms 2013, 150, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, ra111–ra147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Christensen, D.J.; Nicholson, C.; Iliff, J.J.; et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, O.C.; van der Werf, Y.D. The Sleeping Brain: Harnessing the Power of the Glymphatic System through Lifestyle Choices. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlattani, T.; De Luca, D.; Giambartolomei, S.; Bologna, A.; Innocenzi, A.; Bruno, F.; Socci, V.; Malavolta, M.; Rossi, A.; de Berardis, D.; et al. Glymphatic System Dysfunction in Young Adults Hospitalized for an Acute Psychotic Episode: A Preliminary Report from a Pilot Study. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1653144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, G.; Xiong, F.; Gao, F. Glymphatic System Dysfunction Underlying Schizophrenia Is Associated With Cognitive Impairment. Schizophr. Bull. 2024, 50, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, L.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, Z. Reduced Glymphatic Clearance in Early Psychosis. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4665–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eack, S.M.; Mesholam-Gately, R.I.; Greenwald, D.P.; Hogarty, S.S.; Keshavan, M.S. Negative Symptom Improvement during Cognitive Rehabilitation: Results from a 2-Year Trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 209, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanbakhsh, K.; Aivazy, S.; Moradi, A. The Effectiveness of Response Inhibition Cognitive Rehabilitation in Improving the Quality of Sleep and Behavioral Symptoms of Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Kermanshah Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 22, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Modern Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. Parametric measures of effect size. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).