Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Transcription in a Digital Cognitive Assessment for Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Neuropsychological Assessment

1.2. Potential of Speech-to-Text for Digital Assessment

1.3. Prior Work

1.4. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. RCM Digital Screener

- Task 1 (T1) mimicked the California Verbal Learning Test II (CVLT-II) Immediate Word Recall task [28]. It instructed participants to listen to a list of 16 common nouns and then immediately repeat them back from memory. This was repeated five times with the same list.

- Task 2 (T2) was a distractor task to serve as a delay period until Task 3. It instructed participants to spell the word “WORLD” forwards, then backwards.

- Task 3 (T3) mimicked the CVLT-II Short Word Recall task [28]. It instructed participants to freely recall as many words as they could from the original list of 16 nouns they learned in Task 1.

- Task 4 (T4) mimicked the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Verbal Digit Span task [29]. It instructed participants to recall an increasingly long sequence of single-digit numbers forwards, then backwards.

- Task 6 (T6) was a semantic fluency task [31] that instructed participants to say as many animals as they could within 1 min.

- Task 7 (T7) mimicked the Trails Making Test B task [32]. It instructed participants to draw a line on the screen to connect alternating numbers and days of the week.

- Task 8 (T8) mimicked the CVLT-II Long-Delay Free Recall task [28]. It instructed participants to freely recall as many words as they could from the original list of 16 nouns they learned in Task 1, after a longer delay.

- Task 9 (T9) mimicked the CVLT-II Cued Recall task [28]. It instructed participants to recall as many words as they could from the original list of 16 nouns they learned in Task 1, but only of a specifically cued category (e.g., furniture or vegetables). This was repeated four times, once for each category.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Enrollment

2.3.2. Session Orientation

2.3.3. RCM Assessment

2.3.4. Automated STT Processing and Scoring

2.3.5. Manual Transcription Correction

3. Results

3.1. Automated Versus Manual Transcriptions

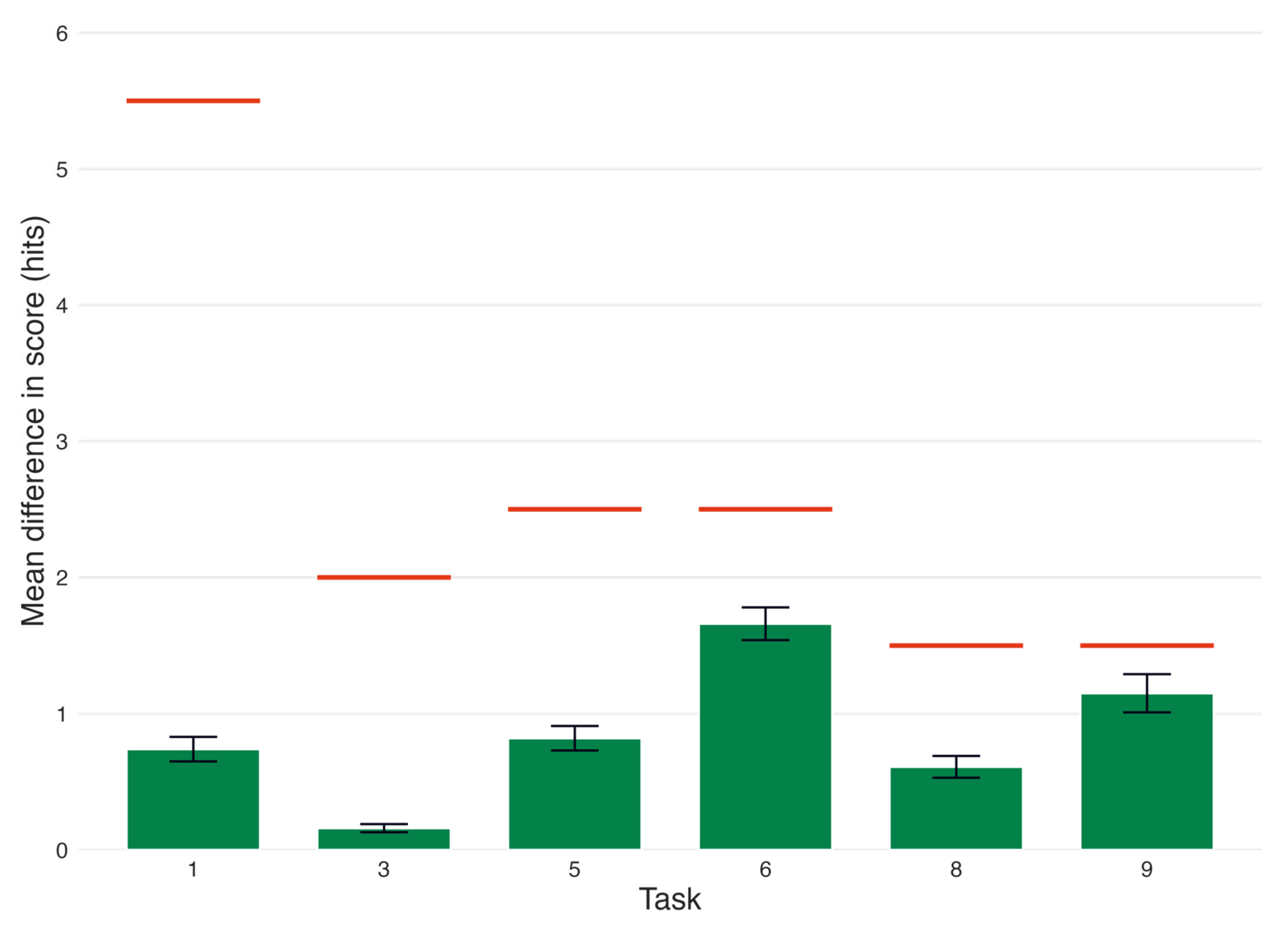

3.2. Effect of Transcription Error on Standardized Scores

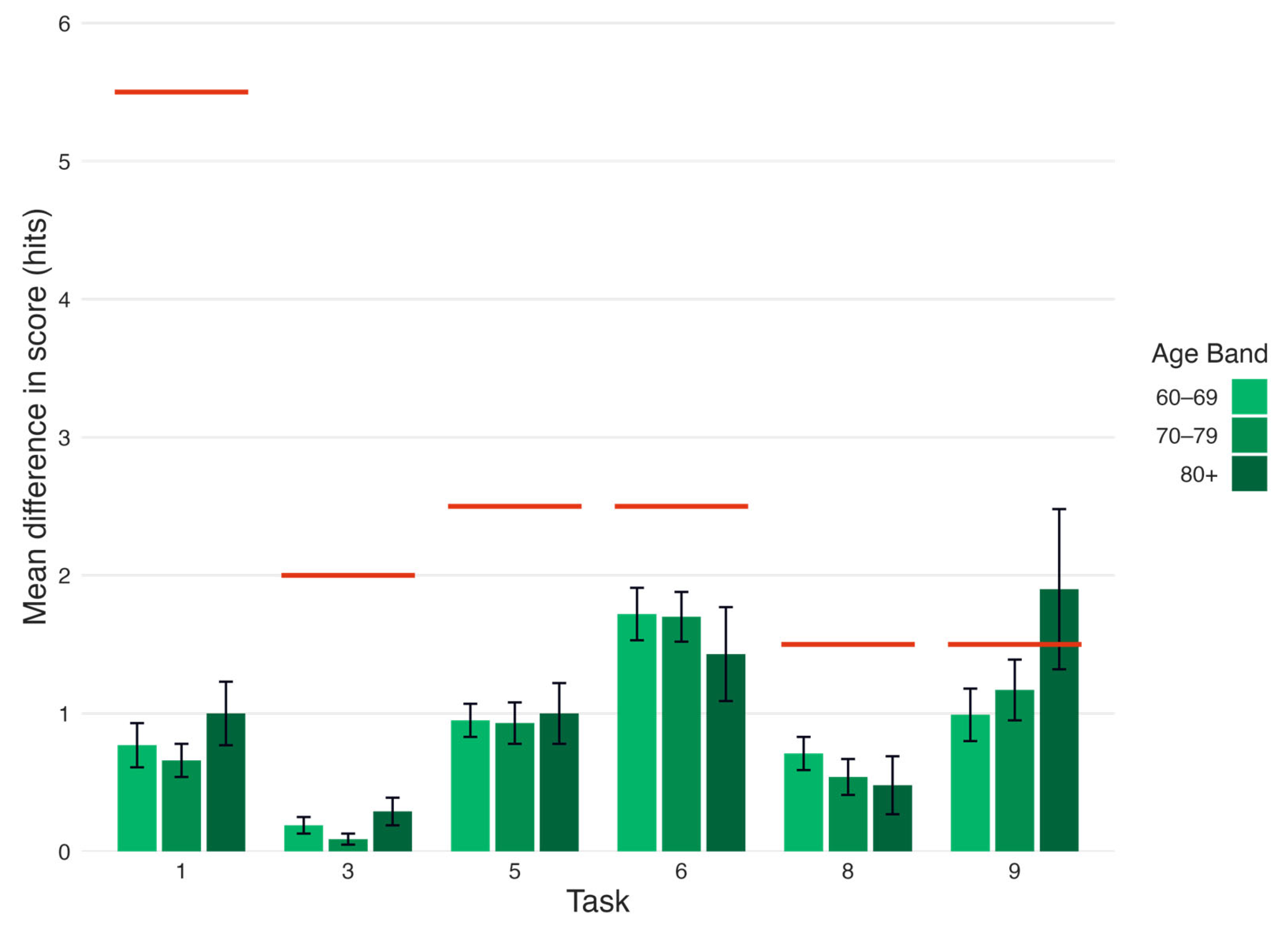

3.3. Effect of Transcription Error on Standardized Scores, by Age Band

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAP | Paper-and-pencil |

| STT | Speech-to-text |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| RQ1 | Research Question 1 |

| RQ2 | Research Question 2 |

| RCM | Remote Cognitive Module |

| T1 | Task 1 |

| CVLT-II | California Verbal Learning Test II |

| T2 | Task 2 |

| T3 | Task 3 |

| T4 | Task 4 |

| T5 | Task 5 |

| T6 | Task 6 |

| T7 | Task 7 |

| T8 | Task 8 |

| T9 | Task 9 |

| QC | Quality control |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| UX | User experience |

| LLM | Large language model |

References

- Possin, K.L.; Moskowitz, T.; Erlhoff, S.J.; Rogers, K.M.; Johnson, E.T.; Steele, N.Z.R.; Higgins, J.J.; Stiver, J.; Alioto, A.G.; Farias, S.T.; et al. The Brain Health Assessment for Detecting and Diagnosing Neurocognitive Disorders. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt, S.; Hornung, J.; Eichenlaub, M.; Jahn, H.; Bullinger, M.; Petersen, C. The Patient with Dementia, the Caregiver and the Doctor: Cognition, Depression and Quality of Life from Three Perspectives. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharre, D.W.; Chang, S.i.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Vrettos, N.E.; Bornstein, R.A. Digitally Translated Self-Administered Gerocognitive Examination (eSAGE): Relationship with Its Validated Paper Version, Neuropsychological Evaluations, and Clinical Assessments. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C. Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Is MCI Too Late? Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2009, 6, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Morris, J.C.; Berg-Weger, M.; Borson, S.; Carpenter, B.D.; del Campo, N.; Dubois, B.; Fargo, K.; Fitten, L.J.; Flaherty, J.H.; et al. Brain Health: The Importance of Recognizing Cognitive Impairment: An IAGG Consensus Conference. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoy, E.; Erlhoff, S.J.; Goode, C.A.; Dorsman, K.A.; Kanjanapong, S.; Lindbergh, C.A.; La Joie, R.; Strom, A.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Lanata, S.C.; et al. BHA-CS: A Novel Cognitive Composite for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2020, 12, e12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment as a Diagnostic Entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arioli, M.; Rini, J.; Anguera-Singla, R.; Gazzaley, A.; Wais, P.E. Validation of At-Home Application of a Digital Cognitive Screener for Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 907496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, S.G.; Franchini, F.; Sancesario, G.; Pistoia, M.; Casacci, P. Comparison of Computerized Testing Versus Paper-Based Testing in the Neurocognitive Assessment of Seniors at Risk of Dementia. In Ambient Assisted Living; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos, C.; Rienzo, A. Digital Cognitive Assessment Tests for Older Adults: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e47487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Fong, C.; Mok, V.C.; Leung, K.; Tong, R.K. Computerized Cognitive Screen (CoCoSc): A Self-Administered Computerized Test for Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Community Social Centers. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 59, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppell, S.; Soto-Ruiz, K.M.; Flores, B.; Dawkins, W.; Smith, I.; Eagleman, D.M.; Katz, Y. A Rapid, Mobile Neurocognitive Screening Test to Aid in Identifying Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (BrainCheck): Cohort Study. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Heik, R.J.; Fahimi, A.; Durazzo, T.C.; Friedman, M.; Bayley, P.J. Evaluation of Adding the CANTAB Computerized Neuropsychological Assessment Battery to a Traditional Battery in a Tertiary Care Center for Veterans. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2020, 27, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, J.; Kawai, H.; Suzuki, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Hirano, H.; Kim, H.; Ihara, K.; Miki, A.; Obuchi, S. Development and Validity of the Computer-Based Cognitive Assessment Tool for Intervention in Community-Dwelling Older Individuals. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichii, S.; Nakamura, T.; Kawarabayashi, T.; Takatama, M.; Ohgami, T.; Ihara, K.; Shoji, M. CogEvo, a Cognitive Function Balancer, Is a Sensitive and Easy Psychiatric Test Battery for Age-Related Cognitive Decline. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahn-Hidalgo, D.; Estes, P.W.; Benabou, R. Validity, Reliability, and Psychometric Properties of a Computerized, Cognitive Assessment Test (Cognivue®). World J. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunardini, F.; Luperto, M.; Romeo, M.; Basilico, N.; Daniele, K.; Azzolino, D.; Damanti, S.; Abbate, C.; Mari, D.; Cesari, M.; et al. Supervised Digital Neuropsychological Tests for Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: Usability and Clinical Validity Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, S.V.S.; Marino, S.E.; Banks, S.; Bernick, C. Using Automatic Speech Recognition to Assess Spoken Responses to Cognitive Tests of Semantic Verbal Fluency. Speech Commun. 2015, 75, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Chignell, M. Developing a Serious Game for Cognitive Assessment: Choosing Settings and Measuring Performance. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium of Chinese CHI, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Woodford, H.J.; George, J. Cognitive Assessment in the Elderly: A Review of Clinical Methods. QJM 2007, 100, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.M.; Iverson, G.L.; Cernich, A.N.; Binder, L.M.; Ruff, R.M.; Naugle, R.I. Computerized Neuropsychological Assessment Devices: Joint Position Paper of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology and the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2012, 27, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, S.; Chollet, G.; Garschall, M.; Tscheligi, M.; Legouverneur, G. Exploring Voice User Interfaces for Seniors. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Rhodes, Greece, 29–31 May 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pentland, S.J.; Fuller, C.M.; Spitzley, L.A.; Twitchell, D.P. Does Accuracy Matter? Methodological Considerations When Using Automated Speech-to-Text for Social Science Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2023, 26, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, V.A.; Chilton, T.D.; Grilli, M.D.; Mehl, M.R. How Ready Is Speech-to-Text for Psychological Language Research? Evaluating the Validity of AI-Generated English Transcripts for Analyzing Free-Spoken Responses in Younger and Older Adults. Behav. Res. 2024, 56, 7621–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziman, K.; Heusser, A.C.; Fitzpatrick, P.C.; Field, C.E.; Manning, J.R. Is Automatic Speech-to-Text Transcription Ready for Use in Psychological Experiments? Behav. Res. 2018, 50, 2597–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafiz, P.; Miskowiak, K.W.; Kessing, L.V.; Jespersen, A.E.; Obenhausen, K.; Gulyas, L.; Żukowska, K.; Bardram, J.E. The Internet-Based Cognitive Assessment Tool: System Design and Feasibility Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2019, 3, e13898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorhaus Advisors. Vorhaus Advisors Digital Strategy Study 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1313944/main-smartphone-usage-share-by-age/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Delis, D.C.; Kramer, J.H.; Kaplan, E.; Ober, B.A. California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd ed.; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R); The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger, P.J.; Damasio, A.R.; Benton, A.L.; Van Allen, M. Neuropsychologic Detection of Abnormal Mental Decline in Older Persons. JAMA 1985, 253, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troyer, A.K.; Moscovitch, M.; Winocur, G. Clustering and Switching as Two Components of Verbal Fluency: Evidence from Younger and Older Healthy Adults. Neuropsychology 1997, 11, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an Indicator of Organic Brain Damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wais, P.E.; Arioli, M.; Anguera-Singla, R.; Gazzaley, A. Virtual Reality Video Game Improves High-Fidelity Memory in Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, J.A.; Volponi, J.J.; Simon, A.J.; Gallen, C.L.; Rolle, C.E.; Anguera-Singla, R.; Pitsch, E.A.; Thompson, C.J.; Gazzaley, A. Integrated Cognitive and Physical Fitness Training Enhances Attention Abilities in Older Adults. npj Aging 2022, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, J.A.; Schachtner, J.N.; Simon, A.J.; Volponi, J.; Javed, S.; Gallen, C.L.; Gazzaley, A. Long-Term Maintenance of Multitasking Abilities Following Video Game Training in Older Adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 103, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Caracciolo, B.; Brayne, C.; Gauthier, S.; Jelic, V.; Fratiglioni, L. Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Concept in Evolution. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 275, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Memory Scale; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

| Task | Automated Score | Manual Score | Pairwise t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Hits (SEM) | |||

| 1 Immediate recall | 47.13 (0.68) | 47.87 (0.68) | t218 = 7.74, p < 0.001 |

| 3 Short-delay recall | 11.21 (0.20) | 11.37 (0.20) | t218 = 4.59, p < 0.001 |

| 5 Lexical fluency | 15.04 (0.32) | 15.87 (0.33) | t215 = 8.93, p < 0.001 |

| 6 Semantic fluency | 16.72 (0.31) | 18.39 (0.33) | t216 = 13.40, p < 0.001 |

| 8 Long-delay recall | 10.50 (0.22) | 11.11 (0.21) | t217 = 7.50, p < 0.001 |

| 9 Categorical recall | 10.56 (0.23) | 11.71 (0.19) | t213 = 8.15, p < 0.001 |

| Task | Diffhits (SEM) | Thresholdn (Hits) | Diffhits > Thresholdn | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Immediate recall | 0.74 (0.09) | 5.5 | False | 219 |

| 3 Short-delay recall | 0.16 (0.03) | 2.0 | False | 219 |

| 5 Lexical fluency | 0.82 (0.09) | 2.5 | False | 216 |

| 6 Semantic fluency | 1.66 (0.12) | 2.5 | False | 217 |

| 8 Long-delay recall | 0.61 (0.08) | 1.5 | False | 219 |

| 9 Categorical recall | 1.15 (0.14) | 1.5 | False | 214 |

| Task | Diffhits (SEM) | Thresholdn (Hits) | Diffhits > Thresholdn | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–69 | ||||

| 1 Immediate recall | 0.77 (0.16) | 5.5 | False | 101 |

| 3 Short-delay recall | 0.19 (0.06) | 2.0 | False | 101 |

| 5 Lexical fluency | 0.95 (0.12) | 2.5 | False | 101 |

| 6 Semantic fluency | 1.72 (0.19) | 2.5 | False | 99 |

| 8 Long-delay recall | 0.71 (0.12) | 1.5 | False | 101 |

| 9 Categorical recall | 0.99 (0.19) | 1.5 | False | 99 |

| 70–79 | ||||

| 1 Immediate recall | 0.66 (0.12) | 5.5 | False | 97 |

| 3 Short-delay recall | 0.09 (0.04) | 2.0 | False | 97 |

| 5 Lexical fluency | 0.93 (0.15) | 2.5 | False | 94 |

| 6 Semantic fluency | 1.70 (0.18) | 2.5 | False | 97 |

| 8 Long-delay recall | 0.54 (0.13) | 1.5 | False | 97 |

| 9 Categorical recall | 1.17 (0.22) | 1.5 | False | 95 |

| 80+ | ||||

| 1 Immediate recall | 1.00 (0.23) | 5.5 | False | 21 |

| 3 Short-delay recall | 0.29 (0.10) | 2.0 | False | 21 |

| 5 Lexical fluency | 1.00 (0.22) | 2.5 | False | 21 |

| 6 Semantic fluency | 1.43 (0.34) | 2.5 | False | 21 |

| 8 Long-delay recall | 0.48 (0.21) | 1.5 | False | 21 |

| 9 Categorical recall | 1.90 (0.58) | 1.5 | True | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gordon, A.M.; Wais, P.E. Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Transcription in a Digital Cognitive Assessment for Older Adults. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101090

Gordon AM, Wais PE. Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Transcription in a Digital Cognitive Assessment for Older Adults. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101090

Chicago/Turabian StyleGordon, Ariel M., and Peter E. Wais. 2025. "Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Transcription in a Digital Cognitive Assessment for Older Adults" Brain Sciences 15, no. 10: 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101090

APA StyleGordon, A. M., & Wais, P. E. (2025). Accuracy of Speech-to-Text Transcription in a Digital Cognitive Assessment for Older Adults. Brain Sciences, 15(10), 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101090