Do Lactating Mothers’ Descriptions of Breastfeeding Pain Align with a Biopsychosocial Pain Reasoning Tool? A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Research Team

2.7. Quality of Study

3. Results

3.1. Participants

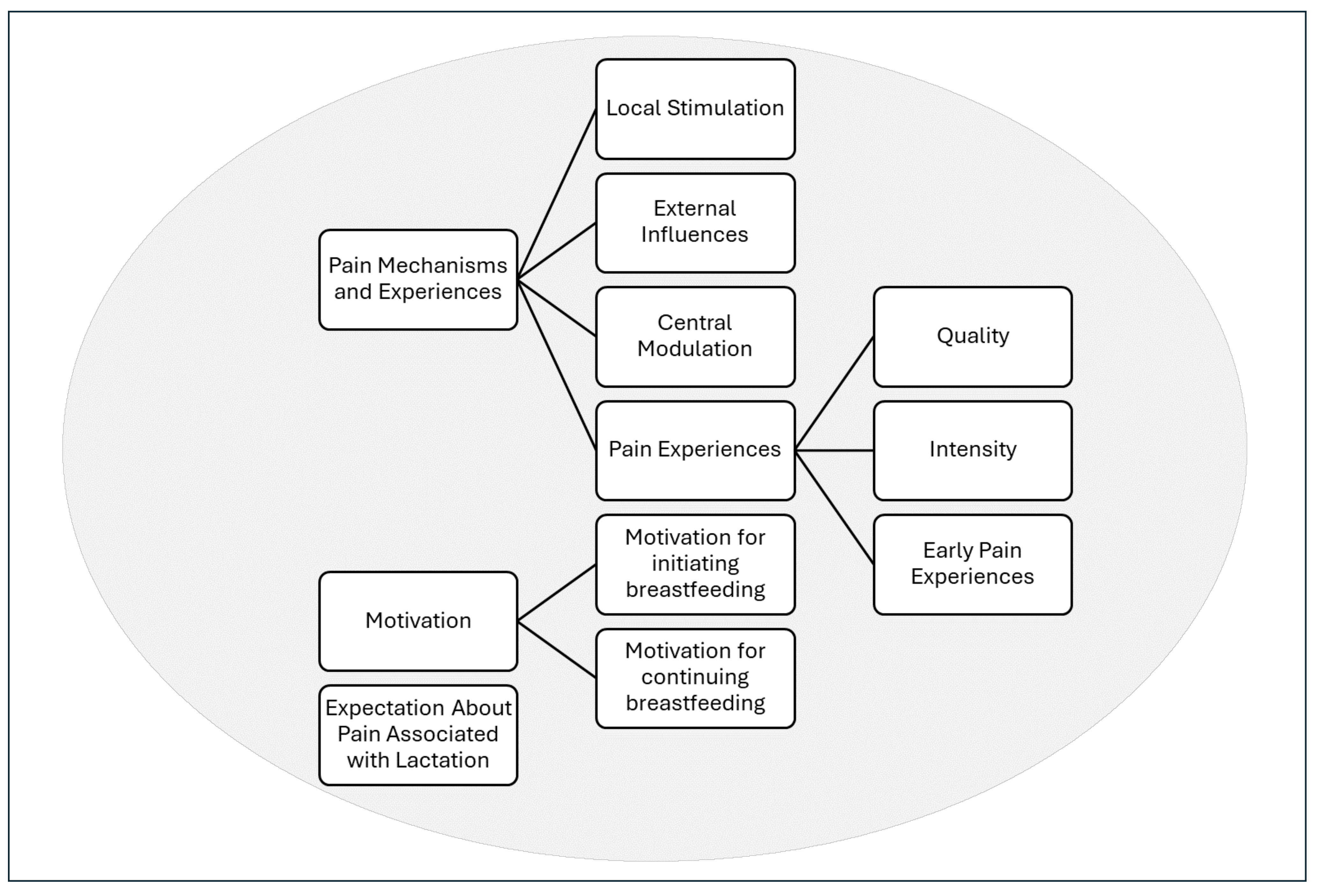

3.2. Results of Analysis

3.3. Theme 1: Pain Mechanisms and Experiences

3.4. Theme 2: “I Have a Goal”—Motivation to Initiate Breastfeeding and to Continue Despite Pain

3.5. Theme 3: “Theory and Practical Is Really Different”—Expectation About Pain Associated with Lactation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Roza, J.G.; Fong, M.K.; Ang, B.L.; Sadon, R.B.; Koh, E.Y.L.; Teo, S.S.H. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.W.; Aris, I.M.; Fok, D.; Soh, S.E.; Chua, M.C.; Lim, S.B.; Saw, S.M.; Kwek, K.; Gluckman, P.D.; Godfrey, K.M.; et al. Determinants of breastfeeding practices and success in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Birth 2016, 43, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Exclusive Breastfeeding for Optimal Growth, Development and Health of Infants. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/exclusive-breastfeeding (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ayton, J.; van der Mei, I.; Wills, K.; Hansen, E.; Nelson, M. Cumulative risks and cessation of exclusive breast feeding: Australian cross-sectional survey. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G.; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.P.P.; Topothai, C.; van der Eijk, Y. Encouraging breastfeeding without guilt: A qualitative study of breastfeeding promotion in the Singapore healthcare setting. Int. J. Womens Health 2024, 16, 1437–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, E.R.; Sakala, C.; Corry, M.P.; Applebaum, S. New Mothers Speak Out: National Survey Results Highlight Women’s Postpartum Experiences; Childbirth Connection: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.H.; Gentry, R.; Anderson, J. Mothers’ reasons for early breastfeeding cessation. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2019, 44, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, E.C.; Li, R.; Scanlon, K.S.; Perrine, C.G.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e726–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.T.; Mantler, T.; O’Keefe-McCarthy, S. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding-related pain. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2019, 44, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, L.H.; Dennerstein, L.; Garland, S.M.; Fisher, J.; Farish, S.J. Psychological aspects of nipple pain in lactating women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 17, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooklin, A.R.; Amir, L.H.; Nguyen, C.D.; Buck, M.L.; Cullinane, M.; Fisher, J.R.W.; Donath, S.M.; CASTLE Study Team. Physical health, breastfeeding problems and maternal mood in the early postpartum: A prospective cohort study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Rance, J.; Bennett, P. Understanding the relationship between breastfeeding and postnatal depression: The role of pain and physical difficulties. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.; Keenan, J.; Wright, N.J.; Hughes, K.; Pearson, R.; Fawcett, H.; Braithwaite, E.C. Investigating the impact of breastfeeding difficulties on maternal mental health. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.R.; Losin, E.A.R. A sociocultural neuroscience approach to pain. Cult. Brain 2017, 5, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.R.; Fu, S.N.; Li, X.; Li, S.X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Pinto, S.M.; Samartzis, D.; Karppinen, J.; Wong, A.Y. The differential effects of sleep deprivation on pain perception in individuals with or without chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 66, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiverstein, J.; Kirchhoff, M.D.; Thacker, M. An embodied predictive processing theory of pain experience. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiech, K.; Shriver, A. Cognition doesn’t only modulate pain perception; It’s a central component of it. AJOB Neurosci. 2018, 9, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R.; Katz, J. Pain in the 21st Century: The neuromatrix and beyond. In Psychological Knowledge in Court; Young, G., Nicholson, K., Kane, A.W., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, J.C.; Ashton, E.; Hardwick, C.M.; Rowan, M.K.; Chia, E.S.; Fairclough, K.A.; Menon, L.L.; Scott, C.; Mather-McCaw, G.; Navarro, K.; et al. Nipple pain in breastfeeding mothers: Incidence, causes and treatments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2015, 12, 12247–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.; McGrath, J.M. Clinical assessment and management of breastfeeding pain. Top. Pain Manag. 2016, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, L.C.; Eccleston, C. Pain and cancer survival: A cognitive-affective model of symptom appraisal and the uncertain threat of disease recurrence. Pain 2017, 158, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe-Steinmuller, N.; Scherbakov, D.; Zhuravlyova, A.; Wager, T.D.; Goldstein, P.; Tesarz, J. Defining suffering in pain: A systematic review on pain-related suffering using natural language processing. Pain 2024, 165, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, P.D. On the relation of injury to pain. The John J. Bonica lecture. Pain 1979, 6, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Eccleston, C. Interoception and pain: Body-mind integration, rupture, and repair. Pain 2025, 166, 1470–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmedt, O.; Luminet, O.; Maurage, P.; Corneille, O. Discrepancies in the definition and measurement of human interoception: A comprehensive discussion and suggested ways forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2025, 20, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.G.; Schloesser, D.; Arensdorf, A.M.; Simmons, J.M.; Cui, C.; Valentino, R.; Gnadt, J.W.; Nielsen, L.; Hillaire-Clarke, C.S.; Spruance, V.; et al. The emerging science of interoception: Sensing, integrating, interpreting, and regulating signals within the self. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria-Garcia, H.; Migeot, J.; Medel, V.; Hazelton, J.L.; Teckentrup, V.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Piguet, O.; Lawor, B.; Northoff, G.; Ibanez, A. Allostatic interoceptive overload across psychiatric and neurological conditions. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 97, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, H.S.; Garfinkel, S.N. Making sense of sensation: A model of interoceptive attribution and appraisal with clinical applications. PsyArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, L.H.; Jones, L.E.; Buck, M.L. Nipple pain associated with breastfeeding: Incorporating current neurophysiology into clinical reasoning. Aust. Fam. Physician 2015, 44, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.E.; O’Shaughnessy, D.F.P. The pain and movement reasoning model: Introduction to a simple tool for integrated pain assessment. Man Ther. 2014, 19, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefeli, M.; Elfering, A. Pain assessment. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15 (Suppl. 1), S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.E.; Hamberg, K.; Westman, G.; Lindgren, G. The meanings of pain: An exploration of women’s descriptions of symptoms. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahurin-Smith, J. Challenges with breastfeeding: Pain, nipple trauma, and perceived insufficient milk supply. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2023, 48, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.T.; O’Keefe-McCarthy, S.; Mantler, T. Moving toward a better understanding of the experience and measurement of breastfeeding-related pain. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 40, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraeni, M.D.; Punthmatharith, B.; Petpichetchian, W. A causal model of breastfeeding duration among working Muslim mothers in Semarang City, Central Java Province, Indonesia. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Lucas, R.; Bernier Carney, K. Perceptions of coping with breastfeeding pain: A secondary analysis. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2025, 70, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.; Eccleston, C.; Williams, A.; Vincent, K.; Linde, M.; Hurley, M.; Laughey, W. Reframing pain: The power of individual and societal factors to enhance pain treatment. Pain Rep. 2024, 9, e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertok, I.A.; Artzi-Medvedik, R.; Arendt, M.; Sacks, E.; Otelea, M.R.; Rodrigues, C.; Costa, R.; Linden, K.; Zaigham, M.; Elden, H.; et al. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding at discharge during the COVID-19 pandemic in 17 WHO European Region countries. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca, K.P.; Lee, E.Y.; Chien, L.Y.; Souza, A.C.P.; Kittikul, P.; Hong, S.A.; Chang, Y.S. Postnatal women’s breastfeeding beliefs, practices, and support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional comparative study across five countries. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.; Graziani, P.; Del-Monte, J. The role of interoceptive attention and appraisal in interoceptive regulation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 714641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 32 ± 4 (22–42) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Chinese | 11 (61.1) |

| Malay | 4 (22.2) |

| Indian | 1 (5.6) |

| Unspecified | 2 (11.1) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| Tertiary diploma or higher | 18 (100) |

| Support at home, n (%) | |

| Spouse only | 1 (5.6) |

| Spouse and family a | 6 (33.3) |

| Spouse and helper b | 7 (38.9) |

| Spouse, family, and helper | 4 (22.2) |

| First time breastfeeding, n (%) | 10 (55.6) |

| Child’s age in weeks, mean ± SD (median; range) | 27.7 ± 28.3 (13; 4–112) |

| Subthemes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| Local Stimulation | So, there shouldn’t be any friction or abrasion. I think that’s what’s causing the pain there and all the wounds. (Eleanor) The pain is because more milk is trying to come in— they’re already filled to capacity; that kind of the stretching and all that. (Felicity) |

| External Influences | If your position is awkward and the baby is uncomfortable, the baby will tend to unlatch, and you would get a shallow latch which would lead to the pain. (Blake) The lactation lady also said, ‘You know her mouth was still very small so it’s not fully, like you know, enclosing the nipple’. (Holly) When you pump it’s like torture—every [pish sound], every suction, it’s very painful. They say you have to select the correct flange size and all those things. (Tina) |

| Central Modulation | If I haven’t eaten or drunk … or not enough sleep … I’ve not [been] able to latch the baby properly or even uh, when I’m busy with other things … then once the baby latch on, then the pain comes then I felt that pain [is] more intense than normal, yeah. (Judith) Yeah, I think it was a couple of occasions, but I didn’t think it was related. But now that it happens to me more … I think there’s definitely a correlation between my stress and more pain, yeah. (Holly) It gives a lot of tension because you want to tend to the child immediately … So, you’re just panicking in a way, so that can affect the overall wellbeing of the breastfeeding journey, which could affect the pain in that sense. (Mandy) |

| Pain experiences: quality | Yeah, that’s the shooting pain for the clogged duct. (Clarissa) You can feel like the needle poking kind—so mostly on the one that is very badly engorged. (Lisa) |

| Pain experiences: intensity | It’s so bad until you cannot wear a bra over it ... I mean loose clothes still can. But you cannot have any pressure on the boobs. (Tina) I think for the sharp pain, it would be a 7 to 8 (out of 10). However, that moment is very brief. So the moment the baby starts sucking, then the pain will fade off. (Blake) So, the initial latch on, it’s like 8, 9/10—so it’s like the toe-curling pain that you, you are just waiting for it to pass [laughter] and after that, then it ease off then you can sense that baby is drinking the milk. (Judith) |

| Pain experiences: early experience | I also know that it is normal for a newborn, at the newborn stage, it can be painful because it is still sensitive and not seasoned yet. (Mandy) It’s my third time already, so I kind of know what breastfeeding is like. But for the baby, he is still new to it. (Eleanor) |

| Subthemes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| Motivation for initiating breastfeeding | Because all the books I read when I was pregnant, about taking care of baby, all recommend breastfeeding until the baby turns one. And most my friends also do breastfeeding. (Tina) As a dietician … we encouraged our pregnant mummies to breastfeed then you ‘jiang jui (say very long)’, you are self psycho-ed also. Also, of course, to save milk powder, it does save a lot of costs. (Orphelia) |

| Motivation for continuing breastfeeding | Okay, because for us for Muslims, we believe that we should feed our child until the age of two. So that’s my ultimate goal, but in the end, even before it reaches two, I got pregnant (laughs). (Clarissa) Six months, according to WHO, it’s like recommended to exclusively breastfeed for six months at least—before introducing any formula or what, … for my first child, I didn’t breastfeed for very long, and I find that she fall sick more often and the severity of the illness was quite bad—she has asthma and eczema. (Judith) First, if I don’t feed her or I don’t pump, the pain will get worse. So if you don’t do it, you will feel more miserable. And so, then you will be like, ‘okay let’s just do it’. And then the second thing is because you know is very strange … after delivery it affects the way you’re think about what you want, for your child. So that guilt feeling and that closeness that you want to have for your child are the main motivating factors. (Mandy) Actually, the nurse was seeing that I was in great pain and they keep offering formula top up … I tell myself if I give in once right, then second time, I will keep giving in. (Orphelia) So, my husband was telling me, then you just give her formula—actually I really wanted to—but I told him like, but I have a goal—like a year of breastfeeding my child. I was very determined to reach that goal. (Nina) |

| Subthemes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| Expectations | I have a friend a young mom … she has three kids already—so every time I see her, she will just whip out only, then she like, “Ya, very easy! Baby want milk you just have to feed her, don’t need to make milk.” Then when I had baby, I was like “Wah, I cannot do that!” (Stella) I think there’s an overhype of how good breastfeeding is. Then—there it’s just not enough to teach mothers the reality of how difficult, tiring and painful breastfeeding is … (Mandy) I am a trained counsellor with the BMSG (Breastfeeding Mother’s Support Group). I know all the breastfeeding knowledge and I also help with the new moms there. But theory and practical is really different. While I know all the theory and I also know what is normal at the newborn stage, it can be painful because it is still sensitive and not seasoned yet. But when I’m actually doing it, it is a very different experience. (Eleanor) |

| Domain | Factors Influencing Pain | Inferred Contributors 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Local Stimulation | Abrasions/nipple damage Bruising of the nipple Infection Breast engorgement Localised breast inflammation Mastitis “Refilling pains” | |

| External Influences | Poor latch or biting Friction Exposure to cold Infant tongue-tie Baby with small mouth or unable to open wide Baby learning to latch Emotionally upset child Size of flange of breast pump Size of nipple shield Shape/size of nipple Ill-fitting bra Clothing on sensitive area of breast/nipple Lack of access to oils and balms Massage (self and other) to engorged breasts | |

| Central Modulation | Lack of understanding from husband Not used to pain Anticipation of painful experience Focus on painful experience Not feeling well Frustration or panic Stress Lack of sleep and tiredness | Frustration Injustice Helplessness Fear Constant pain Fever |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, L.E.; Amir, L.H.; Shi En Chew, N.; Yun Low, S.; Yu Ting Woo, V.; Fok, D.; Peng Mei Ng, Y.; Amin, Z. Do Lactating Mothers’ Descriptions of Breastfeeding Pain Align with a Biopsychosocial Pain Reasoning Tool? A Qualitative Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101087

Jones LE, Amir LH, Shi En Chew N, Yun Low S, Yu Ting Woo V, Fok D, Peng Mei Ng Y, Amin Z. Do Lactating Mothers’ Descriptions of Breastfeeding Pain Align with a Biopsychosocial Pain Reasoning Tool? A Qualitative Study. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101087

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Lester E., Lisa H. Amir, Nicole Shi En Chew, Shi Yun Low, Victoria Yu Ting Woo, Doris Fok, Yvonne Peng Mei Ng, and Zubair Amin. 2025. "Do Lactating Mothers’ Descriptions of Breastfeeding Pain Align with a Biopsychosocial Pain Reasoning Tool? A Qualitative Study" Brain Sciences 15, no. 10: 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101087

APA StyleJones, L. E., Amir, L. H., Shi En Chew, N., Yun Low, S., Yu Ting Woo, V., Fok, D., Peng Mei Ng, Y., & Amin, Z. (2025). Do Lactating Mothers’ Descriptions of Breastfeeding Pain Align with a Biopsychosocial Pain Reasoning Tool? A Qualitative Study. Brain Sciences, 15(10), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15101087