Estimating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Factors in Albania: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background/Rationale

1.2. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

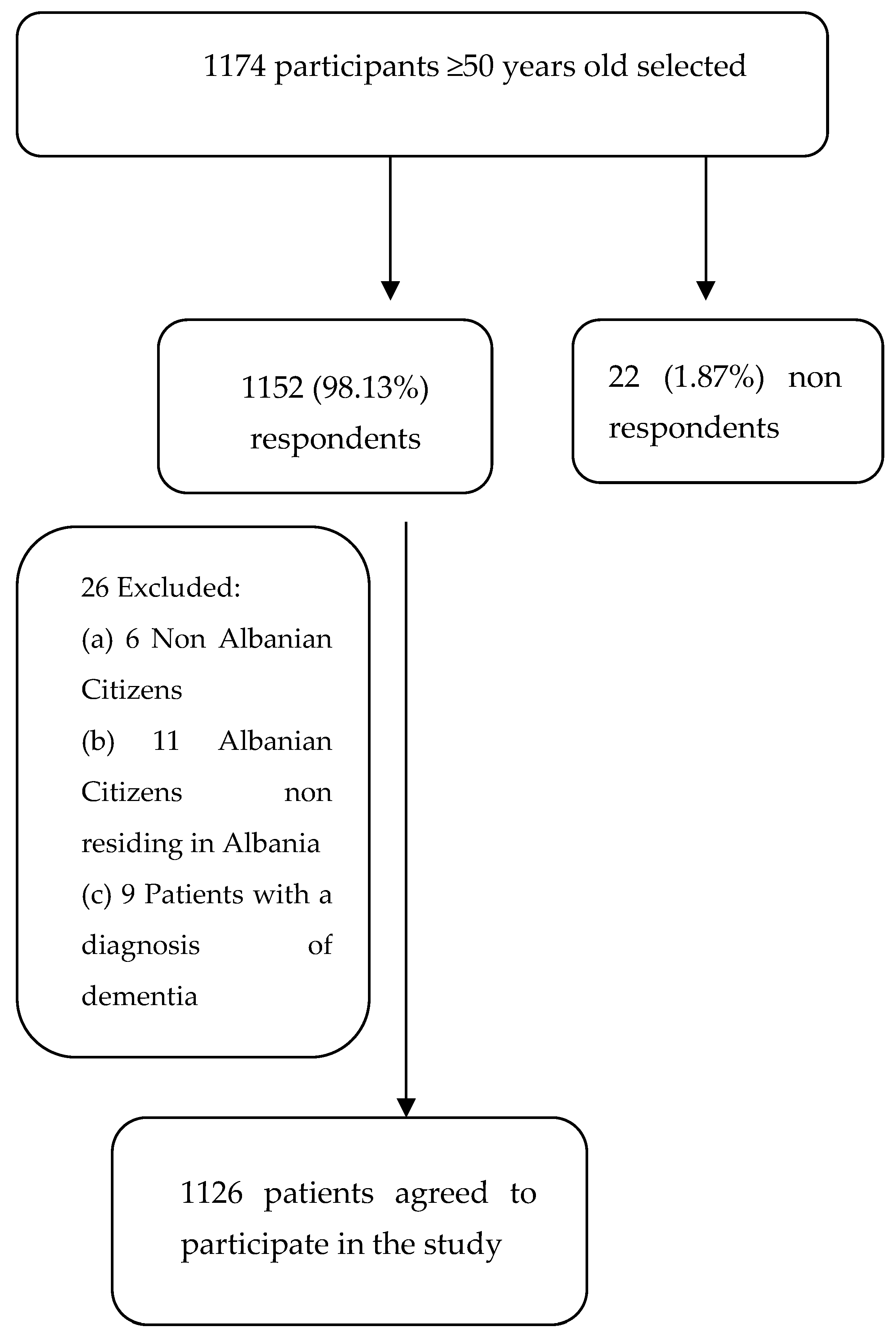

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables

2.4. Data Sources/Measurement

2.5. MMSE

2.6. Early Dementia Questionnaire

2.7. Bias

2.8. Study Size

2.9. Quantitative Variables

2.10. Statistical Methods

2.11. Ethics Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- QUESTIONNAIRE

- I.

- Participant Information

- Name Surname

- Address

- Telephone number

- II.

- Patient companion information (if applicable)

- Name Surname

- Relationship with the patient

- Telephone number

- III.

- Socio-demographic data

- Gender □ F □M

- Age

- Residence (City/Village where you live)

- Civil status

- □

- Single

- □

- Married

- □

- Divorced

- □

- Widow

- 5.

- Living Arrangements

- □

- Alone

- □

- With family

- □

- With friends

- □

- None of the above

- □

- Specify

- 6.

- Education

- □

- No education

- □

- Elementary school

- □

- Middle school

- □

- High school

- □

- University

- □

- PhD, Prof

- 7.

- Employment

- □

- Employed

- □

- Unemployed

- □

- Retired

- 8.

- Smoking

- □

- Smoker

- □

- Non-smoker

- □

- Former smoker

- 9.

- Consumption of alcohol

- □

- Never

- □

- 1–2 drinks a day

- □

- >2 drinks a day

- □

- Several times a week

- □

- Rarely

- IV.

- Clinical data

- 10.

- Physical activity, how many times a week

- □

- Never

- □

- 1–4

- □

- 5–7

- 11.

- Do you suffer or have you suffered from chronic disease/s?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 12.

- Do you suffer or have you suffered from hypertension?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 13.

- Do you suffer from diabetes?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 14.

- Do you suffer or have you suffered from hyperlipidemia?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 15.

- Have you had cerebral ischemia?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 16.

- Have you used antidepressants?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 17.

- Have you suffered from infectious diseases?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 18.

- Do you have a family history of cognitive impairment and/or dementia?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 19.

- Do you have neurological diseases in your family?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

Appendix B

References

- Graham, J.E.; Rockwood, K.; Beattie, B.L.; Eastwood, R.; Gauthier, S.; Tuokko, H.; McDowell, I. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997, 349, 1793–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E. An Overview of Cognitive Impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018, 34, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization.2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/dementia#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- GBD2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: Ananalysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSTAT Albania. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/en/statistical-literacy/the-population-of-albania/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://data.who.int/countries/008 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Harasani, K.; Xhafaj, D.; Lekaj, A.; Veshi, L.; Olvera-Porcel, M.D.C. Screening for mild cognitive impairment among older Albanian patients by clinical pharmacists. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 29, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.E.; Rockwood, K.; Beattie, B.L.; Eastwood, R.; Gauthier, S.; Tuokko, H.; McDowell, I. High prevalence of major neurological disorders in two Albanian communities: Results of a door-to-door survey. Neuroepidemiology 2012, 38, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kruja, J.; Rakacolli, M.; Prifti, V.; Buda, L.; Agolli, D. Epidemiology of dementia in Tirana, Albania. In Proceedings of the 6th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies, Vienna, Austria, 26–30 October 2002; Volume 9, p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; Figuls, M.R.I.; Ciapponi, A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; Cosp, X.B.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; Roqué-Figuls, M.; Ciapponi, A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; BonfillCosp, X.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, CD010783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gillis, C.; Mirzaei, F.; Potashman, M.; Ikram, M.A.; Maserejian, N. The incidence of mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and data synthesis. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2019, 11, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombaugh, T.N.; McIntyre, N.J. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Z.; Aziz, N.A.; Abdul Aziz, A.F.; Razali, R.; Wan Puteh, S.E. Early Dementia Questionnaire(EDQ): A new screening instrument for early dementia in primary care practice. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, A.A.; Mostafa, N.S.; ElSaid, S.M.S. Early Dementia Questionnaire (EDQ): A Screening Instrument for early Dementia among elderly in Cairogovernorate. QJM Int. J. Med. 2021, 114 (Suppl. S1), hcab095.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Palmer, N.; Trejo Ortega, B.; Joshi, P. Cognitive Impairmentin Older Adults: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 45, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSTAT2023. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/11653/popullsia-e-shqiperise-1-janar-2023.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Creavin, S.T.; Wisniewski, S.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; Trevelyan, C.M.; Hampton, T.; Rayment, D.; Thom, V.M.; Nash, K.J.; Elhamoui, H.; Milligan, R.; et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluatedpeople aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016, 2016, CD011145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salzman, C. Do Benzodiazepines Cause Alzheimer’s Disease? Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Number → n (%) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 686 | 60.92 |

| Male | 440 | 39.08 |

| Age range | ||

| 50–54 | 248 | 22.02 |

| 55–59 | 232 | 20.60 |

| 60–64 | 164 | 14.56 |

| 65–69 | 150 | 13.32 |

| 70–74 | 140 | 12.43 |

| 75–79 | 100 | 8.88 |

| 80–85 | 66 | 5.86 |

| 85+ | 26 | 2.31 |

| Residence | ||

| District of Tirana | 894 | 79.39 |

| Other Albanian Districts | 232 | 20.60 |

| Education | ||

| No education | 12 | 1.06 |

| Elementary school | 56 | 4.97 |

| Middle school | 208 | 18.47 |

| High school | 518 | 46.00 |

| University | 310 | 27.53 |

| PhD, Prof | 18 | 1.6 |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 18 | 1.6 |

| Married | 970 | 86.15 |

| Divorced | 14 | 1.24 |

| Widow | 118 | 10.48 |

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Alone | 52 | 4.62 |

| With family | 1070 | 95.03 |

| With friends | 0 | 0 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 534 | 47.42 |

| Unemployed | 112 | 9.95 |

| Retired | 492 | 43.69 |

| MMSE ≤ 18 n (%) | MMSE 19–22 n (%) | MMSE 23–24 n (%) | MMSE 25–30 n (%) | EDQ < 8 n (%) | EDQ ≥ 8 n (%) | X2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 26 (2.31) | 62 (5.51) | 70 (6.22) | 968 (85.97) | 518 (46.00) | 608 (53.99) | ||

| Age range | 12.37 | 0.015 | ||||||

| 50–59 | 4 (0.35) | 28 (2.49) | 24 (2.12) | 422 (37.47) | 220(19.54) | 258 (22.91) | ||

| 60–69 | 16 (1.42) | 18 (1.48) | 20 (1.78) | 258 (22.91) | 124 (11.01) | 188 (16.7) | ||

| 70–74 | 2 (0.18) | 12 (1.06) | 10 (0.89) | 116 (10.30) | 80 (7.10) | 60 (5.33) | ||

| 75–79 | 2 (0.18) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (0.89) | 88 (7.81) | 44 (3.91) | 56 (4.97) | ||

| 80–85+ | 2 (0.18) | 4 (0.35) | 6 (0.53) | 80 (7.10) | 45 (3.98) | 47 (4.18) | ||

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Female | 10 (0.89) | 32(2.84) | 20 (1.78) | 624 (55.42) | 313 (27.79) | 373 (33.13) | ||

| Male | 16 (1.42) | 30 (2.66) | 50 (4.44) | 344 (30.55) | 204 (18.12) | 236 (20.96) | ||

| Residence | 5.27 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Capital City | 20 (1.78) | 54 (4.79) | 62 (5.51) | 758 (67.32) | 426 (37.83) | 468 (41.56) | ||

| Other Cities | 7 (0.62) | 8 (0.71) | 8 (0.71) | 209 (18.56) | 91 (16.16) | 141 (12.52) | ||

| Education | 62.83 | 0.00 | ||||||

| No education | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.18) | 10(0.89) | 1 (0.09) | 11 (0.97) | ||

| Elementary school | 0 (0.00) | 6 (0.53) | 6 (0.53) | 44 (3.91) | 5 (0.44) | 51 (4.53) | ||

| Middle school | 0 (0.00) | 6 (0.53) | 10 (0.89) | 192 (17.05) | 248 (22.02) | 270 (23.98) | ||

| High school | 20 (1.78) | 26 (2.31) | 26 (2.31) | 447 (39.69) | 73 (6.48) | 135 (11.99) | ||

| University, PhD | 6 (0.53) | 26 (2.31) | 26 (2.31) | 269 (23.89) | 185 (16.43) | 143 (12.69) | ||

| Civil status | 6.64 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Single | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.35) | 13 (1.15) | 8 (0.71) | 10 (0.88) | ||

| Married | 24 (2.13) | 58 (5.15) | 60 (5.33) | 829 (73.62) | 458 (40.67) | 512 (45.47) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2(0.18) | 12 (1.06) | 4 (0.35) | 10 (0.89) | ||

| Widow | 2(0.18) | 4 (0.35) | 4 (0.35) | 108 (9.59) | 43 (3.82) | 75 (6.66) | ||

| Living Arrangements | 4.97 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Alone | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.18) | 4 (0.35) | 45 (3.99) | 16 (1.42) | 36 (3.19) | ||

| With family | 26 (2.31) | 60 (5.33) | 66(5.86) | 919 (81.62) | 498 (44.23) | 572 (50.79) | ||

| Employment | 18.43 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Employed | 12 (1.06) | 32 (2.84) | 36 (3.19) | 455 (40.41) | 280 (24.87) | 254 (22.56) | ||

| Unemployed | 4 (0.35) | 8 (0.71) | 8 (0.71) | 92 (8.17) | 44 (3.91) | 68 (6.04) | ||

| Retired | 10 (0.89) | 24 (2.13) | 28 (2.49) | 429 (38.09) | 196 (17.41) | 296 (26.29) |

| MMSE ≤ 18 n (%) | MMSE 19–22 n (%) | MMSE 23–24 n (%) | MMSE 25–30 n (%) | EDQ < 8 n (%) | EDQ ≥ 8 n (%) | X2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 26(2.31) | 62(5.51) | 70(6.22) | 968(85.97) | 518(46.00) | 608(53.99) | ||

| Age range | 12.37 | 0.015 | ||||||

| 50–59 | 4 (0.35) | 28 (2.49) | 24 (2.12) | 422 (37.47) | 220(19.54) | 258 (22.91) | ||

| 60–69 | 16 (1.42) | 18 (1.48) | 20 (1.78) | 258 (22.91) | 124 (11.01) | 188 (16.7) | ||

| 70–74 | 2 (0.18) | 12 (1.06) | 10 (0.89) | 116 (10.30) | 80 (7.10) | 60 (5.33) | ||

| 75–79 | 2 (0.18) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (0.89) | 88 (7.81) | 44 (3.91) | 56 (4.97) | ||

| 80–85+ | 2 (0.18) | 4 (0.35) | 6 (0.53) | 80 (7.10) | 45 (3.98) | 47 (4.18) | ||

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Female | 10 (0.89) | 32(2.84) | 20 (1.78) | 624 (55.42) | 313 (27.79) | 373 (33.13) | ||

| Male | 16 (1.42) | 30 (2.66) | 50 (4.44) | 344 (30.55) | 204 (18.12) | 236 (20.96) | ||

| Smoking | 4.82 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Smoker | 8 (0.71) | 12(1.06) | 24 (2.13) | 108 (9.59) | 57 (5.06) | 95 (8.44) | ||

| Non-smoker | 18 (1.59) | 44 (3.91) | 34 (3.02) | 762 (67.67) | 403 (35.79) | 455 (40.41) | ||

| Former smoker | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.35) | 12(1.07) | 94 (8.35) | 48 (4.26) | 62 (5.51) | ||

| Consumption of alcohol | 1.79 | 0.77 | ||||||

| Never | 14 (1.24) | 32 (2.84) | 26 (2.31) | 612(54.35) | 316 (28.06) | 368 (32.68) | ||

| 1–2 drinks a day | 4 (0.35) | 8 (0.71) | 0(0.00) | 36 (3.19) | 28 (2.48) | 26 (2.31) | ||

| >2 drinks a day | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.18) | 0(0.00) | 18 (1.59) | 8 (0.71) | 12 (23.98) | ||

| Several times a week | 0 (0.00) | 6 (0.53) | 10 (0.89) | 80(7.10) | 40 (3.55) | 56 (4.93) | ||

| Rarely | 8 (0.71) | 14 (1.24) | 28 (2.49) | 228 (20.25) | 126 (11.19) | 152(13.49) | ||

| Physical activity, how many times per week | 14.59 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Never | 4 (0.35) | 24 (2.13) | 19 (1.69) | 301 (26.73) | 137(12.17) | 211 (18.74) | ||

| 1–4 | 10 (0.89) | 18 (1.59) | 18(1.59) | 298 (26.46) | 152 (13.49) | 192 (17.05) | ||

| 5–7 | 10 (0.89) | 20 (1.78) | 34 (3.02) | 364 (32.33) | 226 (20.07) | 202(17.94) | ||

| Chronic Diseases | 6.54 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (1.24) | 28 (2.49) | 42 (3.73) | 584 (51.86) | 285 (25.31) | 383 (34.01) | ||

| No | 12 (1.0) | 35 (3.11) | 28(2.49) | 373 (33.13) | 226 (20.07) | 222 (19.71) | ||

| Hypertension | 11.82 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (1.24) | 24 (2.13) | 34 (3.02) | 444 (39.43) | 206 (18.29) | 310 (27.53) | ||

| No | 14 (1.24) | 39 (3.46) | 36 (3.19) | 521 (46.27) | 306 (27.17) | 304 (26.99) | ||

| Diabetes | 6.86 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (0.18) | 14 (1.24) | 10 (0.89) | 148 (13.14) | 64 (5.68) | 110 (9.77) | ||

| No | 24 (2.13) | 48 (4.26) | 60 (5.33) | 808 (71.76) | 447 (39.69) | 493 (43.78) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 12.41 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (0.35) | 32 (2.84) | 20 (1.78) | 276 (24.51) | 125 (11.10) | 207 (18.38) | ||

| No | 22 (1.95) | 30 (2.66) | 50 (4.44) | 692 (61.46) | 390 (34.63) | 404 (35.88) | ||

| Cerebral ischemia | 9.83 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.18) | 0 (0.00) | 30 (2.66) | 6 (0.53) | 26 (2.31) | ||

| No | 26 (2.31) | 60 (5.33) | 70 (6.22) | 928 (82.41) | 507 (45.03) | 577 (51.24) | ||

| Antidepressants | 45.76 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 11 (0.98) | 97 (8.61) | 16 (1.42) | 92 (8.17) | ||

| No | 27 (2.39) | 61 (5.42) | 60 (5.33) | 868 (77.09) | 497 (44.14) | 519 (46.09) | ||

| Infectious diseases | 1.23 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (1.42) | 48 (4.26) | 46 (4.08) | 662 (58.79) | 345 (30.64) | 427 (37.92) | ||

| No | 10 (0.89) | 14 (1.24) | 24 (2.13) | 298 (26.46) | 167 (14.83) | 179 (15.89) | ||

| Other neurological diseases in the family | 17.91 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.35) | 18 (1.59) | 152 (13.49) | 54 (4.79) | 120 (10.66) | ||

| No | 26 (2.31) | 58 (5.15) | 53 (4.71) | 813 (72.20) | 460 (40.85) | 490 (43.52) | ||

| Family history of cognitive impairment and/or dementia | 8.77 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 8 (0.71) | 11 (0.98) | 161 (14.29) | 64 (5.68) | 116 (10.30) | ||

| No | 26 (2.31) | 54 (4.79) | 60 (5.33) | 802 (71.22) | 448 (39.79) | 494 (43.87) | ||

| Diagnosis | 13.73 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Physician | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.35) | 0 (0.00) | 26 (2.31) | 20 (1.78) | 10 (0.89) | ||

| Neurologist and/or geriatrician | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.18) | 10 (0.89) | 88 (7.81) | 32 (2.84) | 68 (6.04) | ||

| Hospital structure | 6 (0.53) | 4 (0.35) | 12 (1.06) | 50 (4.44) | 22 (1.95) | 50 (4.44) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoxha, M.; Galgani, S.; Kruja, J.; Alimehmeti, I.; Rapo, V.; Çipi, F.; Tricarico, D.; Zappacosta, B. Estimating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Factors in Albania: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100955

Hoxha M, Galgani S, Kruja J, Alimehmeti I, Rapo V, Çipi F, Tricarico D, Zappacosta B. Estimating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Factors in Albania: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(10):955. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100955

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoxha, Malvina, Simonetta Galgani, Jera Kruja, Ilir Alimehmeti, Viktor Rapo, Frenki Çipi, Domenico Tricarico, and Bruno Zappacosta. 2024. "Estimating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Factors in Albania: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study" Brain Sciences 14, no. 10: 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100955

APA StyleHoxha, M., Galgani, S., Kruja, J., Alimehmeti, I., Rapo, V., Çipi, F., Tricarico, D., & Zappacosta, B. (2024). Estimating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Factors in Albania: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sciences, 14(10), 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100955