Brain Correlates of Eating Disorders in Response to Food Visual Stimuli: A Systematic Narrative Review of FMRI Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating: Definitions, Symptomatolog and Epidemiology

1.2. Cerebral Response to Visual Stimuli of Food in Healthy Subjects

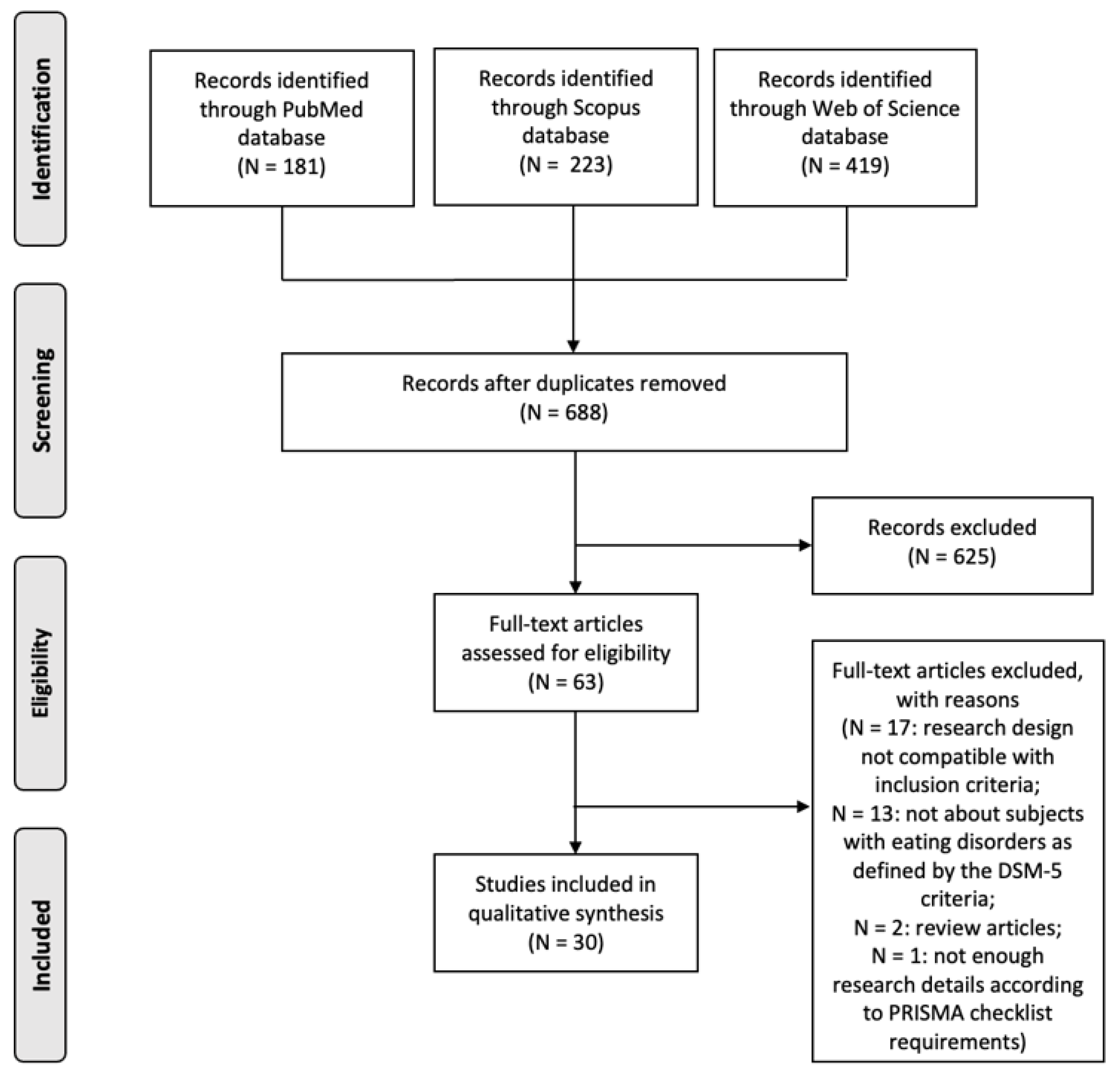

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection of Studies

3. Results

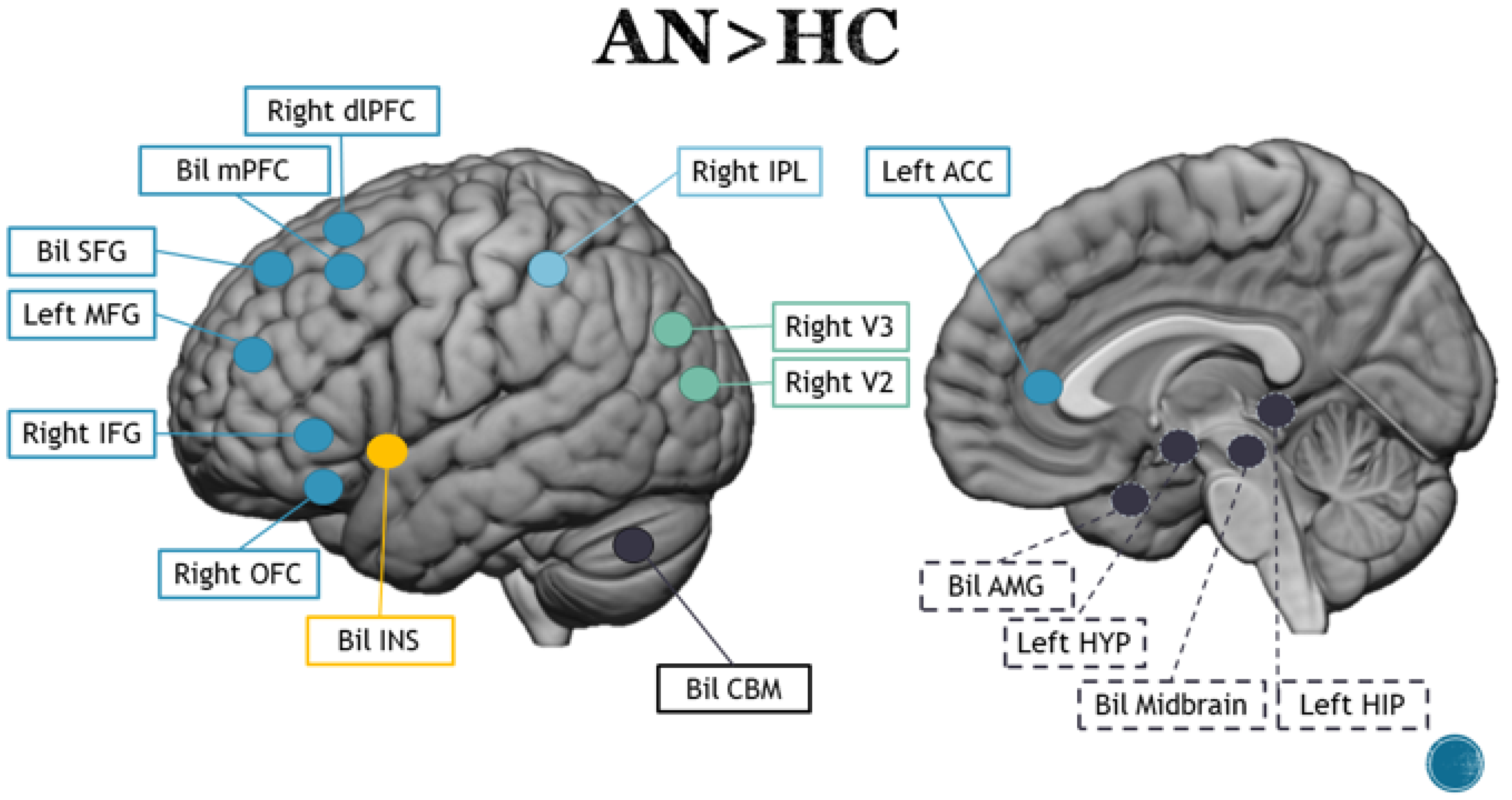

3.1. Anorexia Nervosa

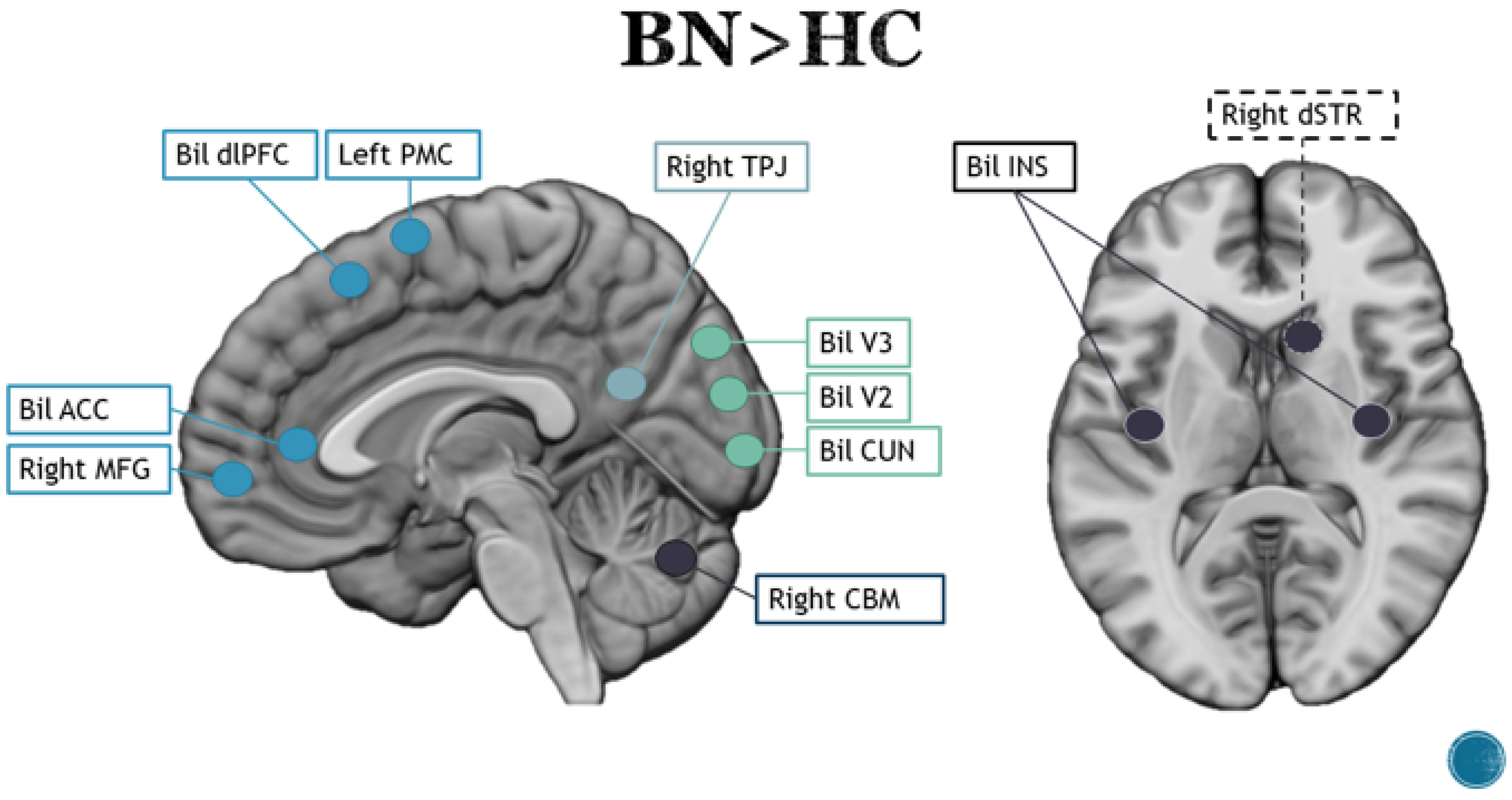

3.2. Bulimia Nervosa

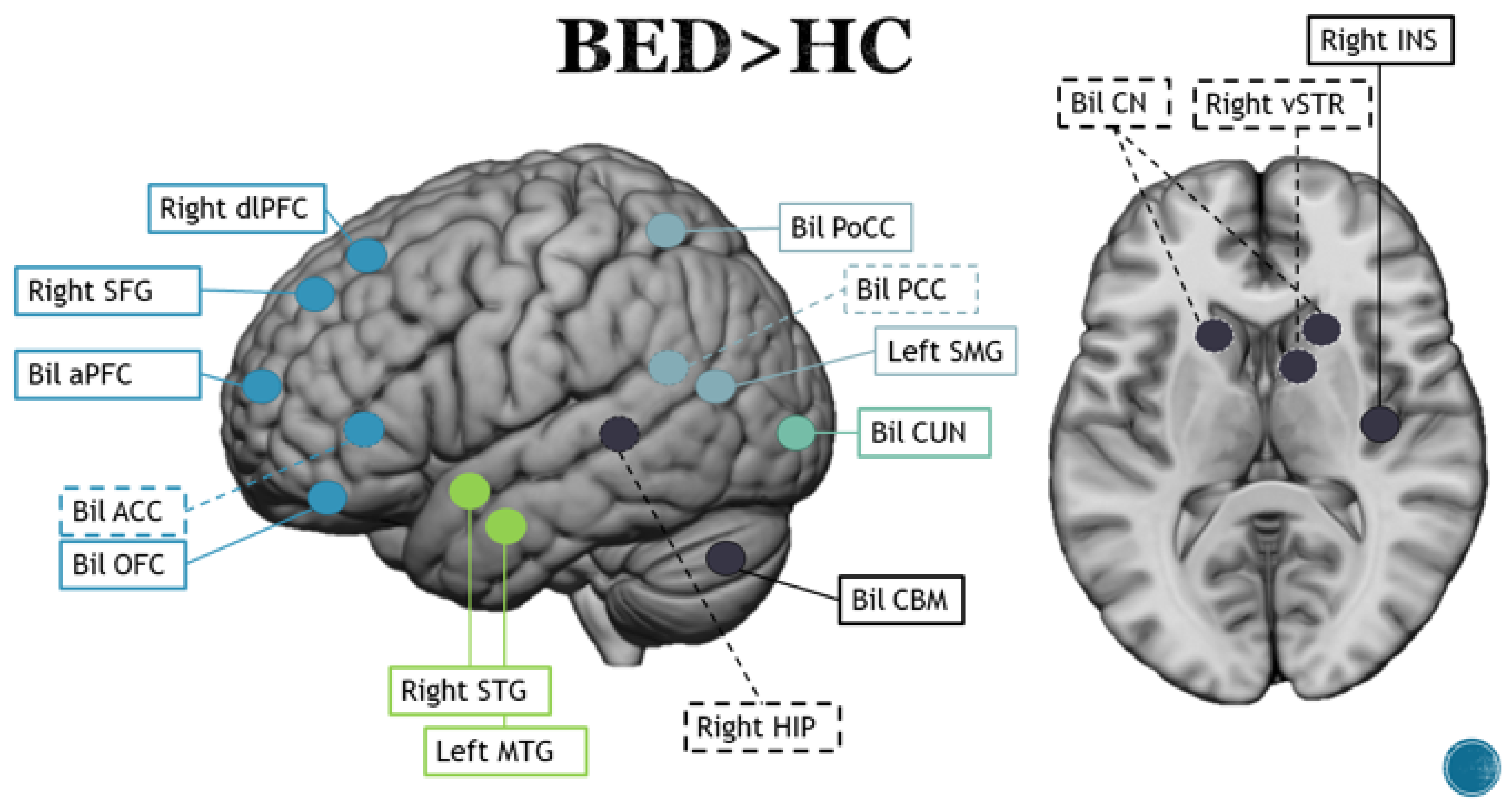

3.3. Binge Eating Disorder

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Paradigm | Stimulus | Conditions | Contrast | Tem-plate | Brain Area | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Passive viewing | High- and low-energy processed food, neutral non-food |

| BED > nonBEDFood > Non-food | MNI | Right INS right ACC left PCC right PCC Left MTG LEft CUN Right CUN Right LG Left PoCG Right V2 Right IPL Right dACC | 34, −4, 12 8, 8, 44 −38, −64, 18 24,−60, 8 −38, −64, 18 −38, −64, 18 16, −84, 26 24, −60, 8 −66, −22, 22 16,−84, 26 54, −38, 24 8, 8, 44 |

| BED > nonBEDHigh > Low | Left MFG Left SMA Left SFG | −16, −8, 50 −16, −8, 50 −16, −8, 50 | |||||

| 2 | Passive viewing (“image to eat the following item”) | Food, IAPS, EmoPics |

| ANFood > neutral supra (coordinates extrapolated from Appendix A) | MNI | left vSTR left vACC Left SOG Left FFG/PHG | −8, −2, −4 * −8, 46, −2 * −30, −90, 28 −26, −90, 28 |

| 3 | Passive viewing (“image to eat the food item or to use the non-food item”) | High and low-calorie food, non-food |

| ANFood > Non-food (RAN + BPAN) (multiple activations in the cerebellum. Selected one representative) | TAL | Left V2 Right dlPFC Right preCUN Left V2 Left CBM Right CBM Right SMA | −18, −74, −23 47, 7, 30 40, −63, 33 −14, −85, −13 −18, −74, −23 * 25, −63, −20 22, −4, 53 |

| BNFood > Non-food | Right V2 Left dlPFC Right INS Left PrCG | 11, −81, −4 −33, 30, 28 −46, 10, −4 −54, −15, 28 | |||||

| HCFood > Non-food | left CBM right STG (INS) right MTG left CN | −4, −63, −20 51, −11, −7 51, −37, 7 −4, 0, 20 | |||||

| AN > BNFood > Non-food (RAN + BPAN) | Right PL Left PCC right PrCG Left ITG | 54, −26, −35 −11, −52, 46 43, −4, 43 −36, −56, −17 | |||||

| BN > ANFood > Non-food (AN = RAN + BPAN) | Right CN Right STG(INS) Left SMA Left ITG Left FFG PCC Right ITG Left IPL Left CBM Left PHG Left PCC Right SMA | 40, −4, 13 14, 7, 21 −43, 4, 43 −58, −4, −10 −4, −67, −10 0, −41, 13 47, −37, 36 −4, −52, 46 −18, −63, −40 −22, 4, −26 −4, −67, 26 25, 7, 53 | |||||

| HC > BNFood > Non-food | Left STG/INS Right STG/INS Left PCC | 54, −26, −7 −51, −15, 0 44, −67, 26 | |||||

| 4 | Passive viewing (“image to eat the following item or to use the non-food item”) | High and low-calories sweet and savory non-food |

| ANFood > Non-food (RAN + BPAN) | TAL | Left CBM Left V2 Right dlPFC mPFC Left CBM Right CBM Right ITG | −25, −66, −16 −14, −83, −7 40, 5, 24 0, 42, 40 −4, −56, −27 25, −62, −14 22, −6, −44 |

| AN > HCFood > Non-food | right V2 right V3 right dlPFC | 29, −67, 15 29, −75, 20 40, 37, 15 | |||||

| HC > ANFood > Non-food | bil CBM right INS | 14, −33, −15 −7, −44, −17 43, −25, 1 | |||||

| RAN > BPANFood > Non-food | left V2 left PHG left ACC | −11, −78, 17 −18, −32, 2 −4, −18, 32 | |||||

| 5 | Passive viewing (“image to eat the food presented in the following images”) | High-calorie food, landscapes |

| AN > HCFood > Non-food | MNI | Left ACC Left mPFC Bil Midbrain | −8, 48, −2 −12, 54, −6 6, −36, −6 −2, −38, −4 |

| 6 | Perceptual discrimination (“same or different”) | High- and low-calorie food, Objects |

| BED > HC(F)Food > Non-food | TAL | Right aPFC Left aPFC | 23, 58, 0 −34, 63, 2 |

| BED > HC(PF)Food > Non-food | Right dlPFC Right OFC Right SFG Right PCC Right TC Right STG Left CBM | 0, 53, 21 29, 25, −9 17, 15, 48 18, −46, 0 29, 6, −9 44, 8, −11 −10, −44, −10 | |||||

| BED > HC(F)high-calorie > Non-food | Left aPFC | −33, 63, 0 | |||||

| BED > HC(PF)high-calorie > Non-food | Right PFC Right MFG Right OFC Left ACC Right CN Right HIP | 4, 23, 51 2, 47, 37 32, 29, −3 −4, 16, −15 8, 7, 14 27, −35, −2 | |||||

| BED > HC(F)low-calorie > Non-food | right aPFC left aPFC left SFG Right CBM | 42, 59, 12 −36, 60, 5 −3, 11, 60 47, −52, −33 | |||||

| BED > HC(PF)low-calorie > Non-food | Left aPFC Right SFG Right dlPFC RIght PCC Left CN Bil aTL Left SMG Right MTG | −16, 59, 3 20, 15, 47 0, 52, 24 21, −48, 3 −2, 22, 3 45, 4, −13 −50, 18, −13 −57, −50, 20 53, −63, 24 | |||||

| HC > BEDFood > Non-food | Left dlPFC Left PrCG Left PCC | −29, 28, 35 −46, 0, 7 −23, −26, 44 | |||||

| HC > BEDhigh-calorie > Low-calorie | Left PoCG Left INS Left PHG Bil CBM | −55, −12, 15 −40, −2, 15 −23, −12, −15 45, −50, −34 −16, −65, −19 | |||||

| HC > BEDhigh-calorie > Non-food | Left PFC Left INS Left ACC Left MTG Left STG Left PoCG | −31, 30, 39 −40, −1, 10 −14, −9, 42 −34, −1, −28 −43, −30, 17 −54, −18, 17 | |||||

| 7 | Passive viewing (“think about how much do you like each image and press a button after every image”) | High and low-calorie food, non-food |

| BEDFood > non- food | MNI (ROI) | AMG CN NAc PUT | All left and right ROIs were combined to form single bilateral structures |

| BEDHigh-calorie > low-calorie | AMG INS NAc PUT | ||||||

| 8 | A Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) task (“tap your index finger on the buzzers if you saw the same image twice in a row”). | High and low-calorie food, sweet and savory food, non-food, high- and low-energy food images associated to emotions (disgust, fear, happy) |

| HC > BEG Low energy disgust> neutral BEG(BN + BED) | MNI | Right CBM Left FFG right CBM right PrCG right CUN left IFG left MFG left PoCG Left PHG | 20, −36, −22 −34, −68, −8 8, −65, −10 38, −2, 30 10, −88, 22 −44, 40, −6 −16, −6, 48 −10, −42, 68 38, −12, −22 |

| BEG > HCLow energy fear > neutral | left PCC Right CBM Right PoCG Right MOG Left PhG | −30, −70, 10 14, −46, −8 46, −22, 24 38, −70, 10 −34, −32, −26 | |||||

| HC > BEGLow energy fear > neutral | Right SFG Right MFG Left CBM Right IFG | 4, 4, 64 32, 50, 26 −22, −82, −38 50, 22, −2 | |||||

| BEG > HCLow energy happy> neutral | left preCUN | −28, −68, 28 | |||||

| HC > BEGHigh energy disgust > neutral | right PCC left LG Left MOG right MTG | 10, −58, 4 −12, −60, −2 −40, −74, 10 42, 4, −34 | |||||

| HC > BEGHigh energy fear > neutral | right SFG right IFG | 10, 2, 66 24, 36, −8 | |||||

| BEG > HCHigh energy happy > neutral | left ACC | −2, 2, −6 | |||||

| 9 | Passive viewing (“attend to the stimuli and queried after each run—hunger ratings and desire to eat”) | Visual and auditory food stimuli, binge food (desserts and high fat salty snacks) non-binge food(fruits and vegetable), Objects |

| BED (BE)Binge food > Non-binge food | TAL/BA | bil PrCG bil IFG left LG Left FG | BA (44) BA (45, 46, 57) BA (17, 18) BA (18, 19) |

| HC(noBE)Binge food > Non binge food | Left IOG Right LG left mOG left ITG | BA (18, 19) BA (17, 18) BA (19) BA (21, 39) | |||||

| BED(BE)Non binge food > Binge food | Right IFG Right FFG | BA (44) BA (18, 19, 37) | |||||

| HC(noBE)Non binge food > Binge food | right LG left MOG Left MTG | BA (17, 18) BA (19) BA (21, 39) | |||||

| 10 | Passive view (“pay attention to the picture”) | high-calorie food, IAPS, |

| AN(H)high-calories vs. non-food | TAL | right CUN left IOC left IPL left INS right MCC left PrCG LEft Thal Left AMG Right AMG right OFC | 16, −100, −2 −38, −94, −2 −44, −40, 58 −34, 8, 10 6,n8, 48 −58, −12, 30 −4, −20, −2 38, −20, −10 −32, −14, −12 46, 24, −16 |

| HC(H)high-calories vs. non-food | Right IOC left IOC left SPL right SPL left ACC left INS Left AMG Right AMG | 38, −70, −8 −40, −72, −14 −22, −60, 56 26, −72, 58 −2, 34, 18 −38, −6, 2 −22, −10, −16 30, 0, −22 | |||||

| AN(S)high-calories vs. non-food | right CUN Left IOC Right SPL Right OFC | 24, −90, −8 −44, −82, −8 28, −64, 54 −44, 22, −22 | |||||

| HC(S)high-calories vs. non-food | right CUN left IOC right SPL right PFC Left OFC Left AMG | 22, −100, 2 −36, −88, −4 26, −62, 56 48, 32, 6 −28, 50, −14 −24, −8, −20 | |||||

| 11 | Passive viewing (“Look at each picture and think how hungry it makes you feel and whether you would like to eat the food or not”) | Food, Objects |

| ANfood > non-food | MNI | left MOG right OG right LG Left IOG right INS left IOG bil SFG bil pMFC left SFG left MFG left MCC left PreCUN right SMG right PoCG | −21, −97, 8 33, −73, −7 15, −88, −4 −30, −76, −4 0, −31, 35 −12, 20, 65 −18, 50, 35 15, 38, 50 −6, 53, 38 9, 17, 68 0, 59, 23 −9, 56, −7 −9, −7, 32 −6, −52, 20 60, −16, 29 −60, −16, 26 |

| ANRECfood > non-food | bil INS left SOrbG left SFG Tlal | −36, −4, 11 39, −1, 2 −21, 35, −13 39, −1, 2 0, −7, 2 | |||||

| HCfood > non-food | right V1 left SFG left SOG left SPL left INS right SMG | 18, −94, 5 −15, 47, 44 −18, −91, 2 −24, −76, 47 −36, −7, 11 −60, −16, 32 | |||||

| AN > ANRECfood > non-food | left FG left V1 left MOG | −33, −58, 11 −21, −58, 8 −30, −73, 5 | |||||

| 12 | Passive viewing (“look at each image and press a button when pictures change”) | high and low-calorie food, objects |

| HC > AN(F)high-calorie food> non-food | MNI | Left HYP Left AMG Left HIP Right OFC Bil INS | −3, −7, −5 −21, −10, −11 −9, −40, 1 36, 23, −11 33, 8, 4 −30, 17, 7 |

| HC > ANrec(F)high-calorie food> non-food | Bil HYP Left AMG Right INS | 9, −7, −5 −6, −10, −5 −24, −10, −11 39, 26, −8 | |||||

| HC > AN(PF)high-calorie food vs. non-food | Left AMG Left INS | −30, −1, −20 −39, −7, 4 | |||||

| AN > ANrec(PF)high-calorie food vs. non-food | right AMG | 15, −1, −17 | |||||

| ANrec > AN(PF)high-calorie food vs. non-food | Bil INS | 36, −10, 13 −39, −7, 4 | |||||

| 13 | Appetite ratings (“look at each picture and rate its valence via button presses”) | Food, IAPS (negative, positive neutral) |

| AN > HCadult high-calorie | TAL | Bil CBM | 28, −70, −24 −18, −70, −24 |

| AN > HCadolescents high-calorie | Right IFG Right mPFC Left INS | 22, 28, −2 24, 39, −14 −27, 26, 15 | |||||

| AN > HCadult low-calorie | Bil CBM | 28, −70, −24 −41, −68, −21 | |||||

| AN > HCadolescents low-calorie | Left CBM Right mPFG Right IPL | −24, −75, −17 24, 39, −14 53, −43, 37 | |||||

| Adult > Adolescentshigh-calorie | Left SPL Right CBM | −2, −68, 56 36, −74, −16 | |||||

| Adolescents > Adultslow-calorie | Bil ACC Bil SFL Left CBM | 8, 35, 13 −3, 33, 24 5, 52, 24 −11, 51, 22 −27, −71, −15 | |||||

| 14 | Passive view (“Look at each picture and think how hungry it makes you feel and whether you would like to eat the food or not”) | Food, objects, Emotion |

| HCFood > Non-food | TAL | Left ACC left MFG left SFL bil INS | −6, 41, 5 −23, 33, 36 −11, 24, 51 34, −1, 11 −34, −7, 11 |

| ANFood > Non-food | right SFL right ACC left MFL AMG left MCC left PreCUN | 14, 50, 10 5, 35, 0 −23, 32, 49 29, −5, −6 −2, −14, 31 −5, −52, 22 | |||||

| AN > HCFood > Non-food | right AMG | 29, −5, −6 | |||||

| HC > ANFood > Non-food | right pMCC | 9, −33, 47 | |||||

| 15 | Passive view (“Look at each picture and think how hungry it makes you feel and whether you would like to eat the food or not”) | Food, objects, Emotion |

| HC > BNFood > Non-food | MNI | Right ACC Right MCC Right mTL | 15, 48,24 −9, −18, 48 45, 12, −27 |

| 16 | Passive view (“imagine tasting the food items or using the non-food items, press a button every time a picture change”) | High-calorie food, Objects |

| ANFood > Non-food | MNI | Bil IFG right SFG left ACC left aINS left PreCUN left CUN bil CBM | −51, 15, 4 59, 9, 18 15,7,60 −3, 21, 40 −35, 11, −4 −13, −47, 42 −15, −83, 8 17, −75, −20 −1, −69, −28 |

| BNFood > Non-food | Left aINS left CUN bil CBM | −35, 23, 6 3, −75, 6 41, −71, −24 −39, −67, −22 | |||||

| HCFood > Non-food | left MFG left CUN left LG Right CBM | −45, 27, 26 −5, −93, 10 −1, −85, −6 −37, −65, −20 | |||||

| AN > HCFood > Non-food | right IFG bil SFG left ACC Right CBM | 59, 9, 14 13, 7, 58 −7, −1, 46 −7, −35, −26 13, −75, −16 | |||||

| HC > ANFood > Non-food | Right IPL | 49, −31, 48 | |||||

| BN > HCFood > Non-food | right MFG right CBM | 41, 21, 28 5, −41, −8 | |||||

| HC > BNFood > Non-food | Right PoCG left IPL | 11, −41, 66 −27, −59, 42 | |||||

| AN > BNFood > Non-food | bil ACC | 1, 19, 42 −11, 17, 32 | |||||

| BN > ANFood > Non-food | right MTG | 53, −63, 12 | |||||

| 17 | Passive viewing | high- and low-calorie food, objects |

| AN > HC (F) | MNI | left HYP left AMG left HIP right OFC Bil INS | −3, −7, −5 −21, −10, −11 −9, −40, 1 36, 23, −11 33, 8, 4 −30, 17, 7 |

| ANrec > HC (F) | Bil HYP left AMG right INS | 9, −7, −5 −6, −10, −5 −24, −10, −11 39, 26, −8 | |||||

| AN > HC (PF) | left AMG left INS | −30, −1, −20 −33, 5, −5 | |||||

| ANrec > HC (PF) | right AMG bil INS | 15, −1, −17 36, −10, 13 −39, −7, 4 | |||||

| 18 | Interference from food stimuli on cognitive control | Food, Objects |

| ED > HC (BN + BED) | MNI | left dlPFC left OFC left PMC right vSTR right PoCC V2-v3 | −18, 44, 48 −24, 20, −8 −42, 8, 54 6, 6, 2 60, 0, 26 16, −92, −4 |

| BN> HCFood > Non-food | Bil dlPFC right dSTR Left PMC Right TPJ Bil V2- v3 | 20, 44, 48 −16, 34, 58 8, 14, 8 −42, 8, 54 −48, −44, −4 26, −70, 2 −34, −72, 34 | |||||

| BED > HCFood > Non-food | Right vSTR right PoCC | 6, 6, 2 60, 0, 28 | |||||

| BN > BEDFood > Non-food | bil dlPFC right dSTR left PMC Right TPJ Bil V2-v3 | 20, 44, 48 −16, 34, 58 6, 14, 10 −40, 8, 52 48, −44, −4 26, −70, 2 −34, −72, 34 | |||||

| BED > BNFood > Non-food | right PoCC left V2-V3 | 60, 0, 28 −28, −86, 0 | |||||

| 19 | Passive viewing | Food, utensils, objects |

| ANhigh > neutral | MNI | Left MOG right IFG bil LG Bil IOG Bil PreCUN right CUN left CUlmen left MTG right SFG left MFG | −48, −76, −4 50, −70, −4 24, −82, −12 −20, −90, −12 40, −76, −10 −30, −88, −14 16, −84, 38 −28, −68, 38 28, −86, 32 −30, −32, −24 −66, −12, −16 16, 56, 22 −46, 50, −12 |

| ANlow > neutral | right INS | 34, 24, 14 | |||||

| ANdeactivations | left MFG right dlPFC | −8, 52, 26 8, 54, 28 | |||||

| ANutensil > neutral | right STG left MFG left claustrum right CC left SupraMG right CG | 40, −38, 8 −42, 2, 54 −28, 6, 22 4, 12, 24 −42, −48, 38 4, −40, 40 | |||||

| HCutensil > neutral | right MFG right dlPFC | 44, 52, 16 50, 46, 10 | |||||

| HCdeactivations | left PreCUN | −22, −70, 32 | |||||

| 20 | Passive viewing | High- and low-calories, sweet and savory, Utensils |

| AN rec> HCfood | MNI | right CN right CBM left PoCG left MFG | 10, 8, 14 6, −76, −14 −42, −28, 42 −34, 4, 50 |

| AN > HCfood | right CBM left MFG | 30, −68, −22 −34, 4, 50 | |||||

| HC > ANfood | right SFG right PreCUN | 14, 40, 50 14, −52, 38 | |||||

| 21 | Rating stimuli inside fMRI (pleasant, neutral or unpleasant), “keep looking at each picture for as long as it was presented” | High-caloric, sweet and savory food, Objects |

| AN < HCS | TAL | left IPL | −50, −28, 26 |

| AN < HCH | right LG | 12, −82, −8 | |||||

| ANS | right IOG right CBM left LG left CBM | 27, −91, −6 30, −77, −21 −18, −96, −3 −18, −86, −21 | |||||

| ANH | left CUN right FG | −24, −93, −2 24, −79, −14 | |||||

| ANS > H | right MOG | 18, −93, 12 | |||||

| HCS | right CUN right MOG left CUN left IOG | 18, −93, 0 30, −90, 10 −12, −99, 0 −12, −91, −8 | |||||

| HCH | right LG Right FG Left LG | 21, −91, −3 33, −71, −17 −15, −96, −3 | |||||

| HCS > H | right ACC left OFC left MTG | 15, 19, 27 −33, 40, −12 −48, −10, −15 | |||||

| 22 | Passive viewing (“focus on how much you want each of the different foods, right now”) | High/low-calorie, savory and sweet, |

| HC > ANfood > baseline | MNI | right PoCG right PreCUN left SPL right PoCG | 40, −30, 58 2, −66, 26 −40, −44, 56 48, −24, 58 |

| AN > HChigh-calorie AND HC > ANlowcalories | right LFP | 28, 64, 0 | |||||

| HC > ANlowcalories | right vmPFC right dlPFC right dmPFC right SMG | 8, 52, −20 44, 28, 32 8, 52, 44 62, −48, 16 | |||||

| 23 | Passive viewing | High- and low-calorie disgusting item, neutral (household articles) |

| BEDFood > Non-food | MNI | left MOG left MFG Bil INS Bil ACC Bil lOFC Bil mOFC | −15, −96, 0 −24, 30, −21 −36, 6, −15 39, 0, −3 −9, 39, −3 15, 36, 15 −24, 30, −21 21, 27, −21 0, 36, −15 3, 36, −15 |

| BNFood > Non-food | right LG Bil INS Bil ACC Bil lOFC left AMG right vSTR | 15, −84, −9 −39, 6, −9 39, 3, −3 −3, 18, 21 6, 18, 21 −27, 33, −12 24, 24, −18 −30, 3, −18 12, 9, −6 | |||||

| HCFood > Non-food | right LG right IFG bil INS Bil ACC Bil lOFC left mOGC Bil AMG left vSTR | 9, −93, −6 27, 27, −18 −36, −6, 6 30, 24, −21 −3, 39, 9 3, 33, 12 −27, 33, −15 27, 27, −18 −9, 63, −3 −18, −3, −21 27, 0, −27 −9, 9, −6 | |||||

| BED > BNFood > Neutral | right lOFC right mOFC | 36, 33, −12 12, 27, −12 | |||||

| BED > HCFood > Neutral | Bil mOFC | 0, 33, −18 6, 36, −12 | |||||

| BN > BEDFood > Neutral | Bil ACC right INS | 0, 15, 21 3, 15, 24 39, −3, −12 | |||||

| BN > HCFood > Neutral | Bil ACC Bil INS | −6, 21, −6 6, 15, 21 38, −3, −9 −36, −6, −9 | |||||

| 24 | Passive view (“Imagine eating/using the food/object presented”) | Low- and high-calorie and sweet and savory foods, Objects |

| AverageFood > non-food (AN, ANrec, HC—supplementary) | MNI | right MOG left LG left MOG right LG left FFG left CBM right FFG Right AG Bil HPC left MFG vermis left IFG left SupraMG right PoCG left PCL left PreCUN left ACC | 30, −84, 6 22, −76, −10 −26, −84, 2 18, −88, −5 −25, −72, −14 −30, −54, −18 34, −56, −18 26, −60, 42 −22, −32, −2 22, −28, −6 −50, 16, 38 2, −40, −6 −46, 12, 30 50, −28, 42 62, −16, 38 −14, −32, 70 −2, −40, 62 −2, 4, 30 |

| 25 | Passive view (“Look at each picture and think how hungry it makes you feel and whether you would like to eat the food or not”) | savory and sweet, objects, Emotional stimuli (IAPS) |

| ANrecFood > Non-food | TAL | bil mPFC right lPFC left lPFC right IFG right ACC left CBM | −1, 54, 19 1, 54, 19 36, 53, −7 −48, 44, 6 51, 17, 12 5, 22, 32 −40, −71, −71 |

| ANrec > HCFood > Non-food | bil ACC left CBM | 3, 40, 29 −30, −62, −28 | |||||

| HC > ANrecFood > Non-food | left SPL left IPL left V1 | −34, −45, 46 −51, −20, 21 −14, −75, 29 | |||||

| ANrec > ANFood > Non-food | left PFC left mPFC right dACC right lPFC left OP left CBM | −5, 58,−15 2, 47, 28 6, 23, 33 50, 19, 12 −34, −60, 39 −34, −62, −22 | |||||

| AN > ANrecFood > Non-food | right LG | 5, −61, 6 | |||||

| 26 | Passive view (“Look at each picture and think how hungry it makes you feel”) | savory and sweet, objects, Emotional stimuli (IAPS) |

| ED > HCFood > Non-food | TAL | left vmPFC | −16, 28, −17 |

| HC > EDFood > Non-food | left lPFC left dlPFC left IPL left OC left CBM | −40, 42, 3 −49, 9, 26 −36, −42, 48 −15, −72, 33 −32, −74, −4 | |||||

| AN > HCFood > Non-food | Left vmPFC Right LG | −13, 29, −20 19, −72,−4 | |||||

| HC > ANFood > Non-food | left IPL Left CBM | −33, −47, 44 −32, −73, −20 | |||||

| BN > HCFood > Non-food | Left vmPFC Left LG Bil CBM | −17, 35, −13 −38, −60, −9 2, −54, −20 | |||||

| HC > BNFood > Non-food | left dlPFC left lPFC | −46, 23, 26 −42, 40, 0 | |||||

| AN > BNFood > Non-food | right apicalPFC right lPFC right LG | 13, 64, −2 47, 36, −5 17, −72, 1 | |||||

| BN > ANFood > Non-food | right CBM | 29, −57, −24 | |||||

| 27 | Passive viewing (“imagine eating these foods” or “imagine using these tools”) | food, body images, objects |

| BNFood > Non-food | TAL | Left SFG Left MFG Left LG | −3.6, 55.6, 29.7 0, 25.9, 36.3 −14.4, −85.2, 0 |

| BN > HCFood > Non-food | Bil CUN | 21.7, 77.7, 8.3 −21.7, 77.7, 8.3 | |||||

| HCFood > Non-food | left MFG right CUN | −3.6, 11.1, 42.9 21.7, −77.8, 9.9 | |||||

| 28 | Distractive task(related to EMA) (“indicate stimulus orientation (landscape vs. portrait) with the button”) | Sweet and savory food, IAPs |

| BNfood > neutral | MNI | Bil AMG | - |

| 29 | Passive viewing (VAS on anxiety) | high and low-calorie, sweet and savory food, objects |

| HCFood > Non-food | MNI | left CN left V1 Left ACC right CN left Thal left LG | −12, 9, −12 −10, −98, −12 −3, 36, 4 10, 10, −12 −3, −20, 3 −10, −40, −3 |

| HCNon-food > Food | left mOL right CUN left SPL right PreCUN right mTL right IPL | −45, −70, 1 14, −78, 30 −24, −56, 66 12, −52, 54 51, −56, −2 54, −48, 40 | |||||

| HC > ANFood > Non-food | right pgACC | 6, 48, 12 | |||||

| 30 | Passive viewing (“how hungry it makes you feel” VAS on appeals every block) | Food (sweet, processed snack, fast food, meats/fruit), Objects |

| ANfood > non-food | MNI | Bil V1 Bil LG Bil IOG Right CUN | 2, −87, −10 |

| ANNon-food > food | right OG right mTL right CUN right PreCUN right SPL right AG left MTL left STG left OG left SMG | 44, −76, 23 −54, −39, 11 |

References

- Gordon, R.A. Anorexia and Bulimia: Anatomy of a Social Epidemic; Basil Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0631148515. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fini, G.; Veglia, F. Life themes and attachment system in the narrative self-construction: Direct and indirect indicators. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köster, E.P.; Mojet, J. From Mood to Food and from Food to Mood: A Psychological Perspective on the Measurement of Food-Related Emotions in Consumer Research. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Centis, E.; Marzocchi, R.; El Ghoch, M.; Marchesini, G. Major Factors for Facilitating Change in Behavioral Strategies to Reduce Obesity. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2013, 6, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avena, N.M.; Bocarsly, M.E. Dysregulation of Brain Reward Systems in Eating Disorders: Neurochemical Information from Animal Models of Binge Eating, Bulimia Nervosa, and Anorexia Nervosa. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Urbán, R.; Szabo, A.; Magi, A.; Eisinger, A.; Demetrovics, Z. Emotion Dysregulation Mediates the Relationship between Psychological Distress, Symptoms of Exercise Addiction and Eating Disorders: A Large-Scale Survey among Fitness Center Users. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2022, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, Z.; Messer, M.; Anderson, C.; Liu, C.; Linardon, J. Which Dimensions of Emotion Dysregulation Predict the Onset and Persistence of Eating Disorder Behaviours? A Prospective Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monell, E.; Clinton, D.; Birgegård, A. Emotion Dysregulation and Eating Disorder Outcome: Prediction, Change and Contribution of Self-image. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 95, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders in Europe: Prevalence, Incidence, Comorbidity, Course, Consequences, and Risk Factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall Dahlgren, C.; Wisting, L.; Rø, Ø. Feeding and Eating Disorders in the DSM-5 Era: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Rates in Non-Clinical Male and Female Samples. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000–2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagnino, M.; Civilotti, C.; Cussino, M.; Callerame, C.; Fernandez, I. EMDR in Anorexia Nervosa: From a Theoretical Framework to the Treatment Guidelines. In Eating Disorders—A Paradigm of the Biopsychosocial Model of Illness; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbert, K.M.; Racine, S.E.; Klump, K.L. Research Review: What We Have Learned about the Causes of Eating Disorders—A Synthesis of Sociocultural, Psychological, and Biological Research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, K.J. Animal Models of Human Psychology: Critique of Science, Ethics, and Policy; Hogrefe & Huber: Seattle, WA, USA, 1998; ISBN 088937189X. [Google Scholar]

- Overton, A.; Selway, S.; Strongman, K.; Houston, M. Eating Disorders—The Regulation of Positive as Well as Negative Emotion Experience. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2005, 12, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo, G.; Wiemerslage, L.; Swenne, I.; Zhukowsky, C.; Salonen-Ros, H.; Larsson, E.-M.; Gaudio, S.; Brooks, S.J.; Schiöth, H.B. Limbic-Thalamo-Cortical Projections and Reward-Related Circuitry Integrity Affects Eating Behavior: A Longitudinal DTI Study in Adolescents with Restrictive Eating Disorders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172129. [Google Scholar]

- Friederich, H.-C.; Wu, M.; Simon, J.J.; Herzog, W. Neurocircuit Function in Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, A.E.; Hong, F.; Amir, C.; Tarullo, A.R.; Samkavitz, A.; Ashy, M.; Malley-Morrison, K. Relationships among Childhood Maltreatment, Limbic System Dysfunction, and Eating Disorders in College Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farstad, S.M.; McGeown, L.M.; von Ranson, K.M. Eating Disorders and Personality, 2004–2016: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 46, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Stein, D.; Maguire, S. Has the Time Come for a Staging Model to Map the Course of Eating Disorders from High Risk to Severe Enduring Illness? An Examination of the Evidence. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 9, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, C.L.; Su, J.; Hlynsky, J.A.; Goldner, E.M.; Gao, M. The Mortality Rate from Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 38, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehler, P.S.; Watters, A.; Joiner, T.; Krantz, M.J. What Accounts for the High Mortality of Anorexia Nervosa? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhausen, H.-C. The Outcome of Anorexia Nervosa in the 20th Century. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.I.; Hiripi, E.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Kessler, R.C. The Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.L.; Byrne, S.M.; Oddy, W.H.; Crosby, R.D. DSM–IV–TR and DSM-5 Eating Disorders in Adolescents: Prevalence, Stability, and Psychosocial Correlates in a Population-Based Sample of Male and Female Adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.A.; Crow, S.J.; Le Grange, D.; Swendsen, J.; Merikangas, K.R. Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grange, D.; Swanson, S.A.; Crow, S.J.; Merikangas, K.R. Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Presentation in the US Population. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangweth-Matzek, B.; Rupp, C.I.; Hausmann, A.; Gusmerotti, S.; Kemmler, G.; Biebl, W. Eating Disorders in Men: Current Features and Childhood Factors. Eat. Weight Disord. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2010, 15, e15–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raevuori, A.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Hoek, H.W. A Review of Eating Disorders in Males. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.M.; Zatorre, R.J.; Dagher, A.; Evans, A.C.; Jones-Gotman, M. Changes in Brain Activity Related to Eating Chocolate: From Pleasure to Aversion. Brain 2001, 124, 1720–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubeati, S.; Avery, A.; Tench, C.R.; Lobo, D.N.; Salter, A.; Eldeghaidy, S. Mapping Brain Activity of Gut-Brain Signaling to Appetite and Satiety in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Functional Neuroimaging Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 136, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Schwab, Z.J.; Weber, M.; Kipman, M.; DelDonno, S.R.; Weiner, M.R.; Rauch, S.L. Daytime Sleepiness Affects Prefrontal Regulation of Food Intake. Neuroimage 2013, 71, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.K.; Martin, A.; Barsalou, L.W. Pictures of Appetizing Foods Activate Gustatory Cortices for Taste and Reward. Cereb. Cortex 2005, 15, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, J.; Rolls, E.T.; Francis, S.; Bowtell, R.; McGlone, F.; Kobal, G.; Renner, B.; Ahne, G. Sensory-Specific Satiety-Related Olfactory Activation of the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A.N.; Yokum, S.; Orr, P.T.; Stice, E.; Corbin, W.R.; Brownell, K.D. Neural Correlates of Food Addiction. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, E.P.; Ivan, V.J.; Friedman, J.M.; Stern, S.A. Higher-Order Inputs Involved in Appetite Control. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, N.B.; Krebs, L.; Kobiella, A.; Grimm, O.; Pilhatsch, M.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Zimmermann, U.S.; Smolka, M.N. Fasting Levels of Ghrelin Covary with the Brain Response to Food Pictures. Addict. Biol. 2013, 18, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; White, D.J.; Scholey, A. Resting State FMRI Reveals Differential Effects of Glucose Administration on Central Appetite Signalling in Young and Old Adults. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBar, K.S.; Gitelman, D.R.; Parrish, T.B.; Kim, Y.H.; Nobre, A.C.; Mesulam, M.M. Hunger Selectively Modulates Corticolimbic Activation to Food Stimuli in Humans. Behav. Neurosci. 2001, 115, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, O.; Jacob, M.J.; Kroemer, N.B.; Krebs, L.; Vollstädt-Klein, S.; Kobiella, A.; Wolfensteller, U.; Smolka, M.N. The Personality Trait Self-Directedness Predicts the Amygdala’s Reaction to Appetizing Cues in fMRI. Appetite 2012, 58, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.M.; Dougherty, D.D.; Rauch, S.L.; Emans, S.J.; Grace, E.; Lamm, R.; Alpert, N.M.; Majzoub, J.A.; Fischman, A.J. Neuroanatomy of Human Appetitive Function: A Positron Emission Tomography Investigation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 27, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.E.; Stutz, S.J.; Hommel, J.D.; Anastasio, N.C.; Cunningham, K.A. Anterior Insula Activity Regulates the Associated Behaviors of High Fat Food Binge Intake and Cue Reactivity in Male Rats. Appetite 2019, 133, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schur, E.A.; Kleinhans, N.M.; Goldberg, J.; Buchwald, D.; Schwartz, M.W.; Maravilla, K. Activation in Brain Energy Regulation and Reward Centers by Food Cues Varies with Choice of Visual Stimulus. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewaybricker, L.E.; Melhorn, S.J.; Rosenbaum, J.L.; Askren, M.K.; Tyagi, V.; Webb, M.F.; De Leon, M.R.B.; Grabowski, T.J.; Schur, E.A. Reassessing Relationships between Appetite and Adiposity in People at Risk of Obesity: A Twin Study Using FMRI. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 239, 113504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Thanos, P.K.; Logan, J.; Alexoff, D.; Ding, Y.-S.; Wong, C.; Ma, Y. Low Dopamine Striatal D2 Receptors Are Associated with Prefrontal Metabolism in Obese Subjects: Possible Contributing Factors. Neuroimage 2008, 42, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, S. Appetite and Reward. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2010, 31, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Rodriguez, O.; Burrows, T.; Pursey, K.M.; Stanwell, P.; Parkes, L.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Verdejo-Garcia, A. Food Addiction Linked to Changes in Ventral Striatum Functional Connectivity between Fasting and Satiety. Appetite 2019, 133, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, I.; Kube, J.; Morys, F.; Schrimpf, A.; Kanaan, A.S.; Gaebler, M.; Villringer, A.; Dagher, A.; Horstmann, A.; Neumann, J. Liking and Left Amygdala Activity during Food versus Nonfood Processing Are Modulated by Emotional Context. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 20, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsen, L.M.; Zarcone, J.R.; Thompson, T.I.; Brooks, W.M.; Anderson, M.F.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Nollen, N.L.; Savage, C.R. Neural Mechanisms Underlying Food Motivation in Children and Adolescents. Neuroimage 2005, 27, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringelbach, M.L. Food for Thought: Hedonic Experience beyond Homeostasis in the Human Brain. Neuroscience 2004, 126, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zald, D.H. The Human Amygdala and the Emotional Evaluation of Sensory Stimuli. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 41, 88–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Cai, W.; Ryali, S.; Supekar, K.; Menon, V. Distinct Global Brain Dynamics and Spatiotemporal Organization of the Salience Network. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, J.D.; Lawrence, A.D.; Van Ditzhuijzen, J.; Davis, M.H.; Woods, A.; Calder, A.J. Individual Differences in Reward Drive Predict Neural Responses to Images of Food. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 5160–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, T.A.; O’doherty, J.; Camerer, C.F.; Schultz, W.; Rangel, A. Dissociating the Role of the Orbitofrontal Cortex and the Striatum in the Computation of Goal Values and Prediction Errors. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 5623–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, A.P.; de Hernandez, C.G.P.; Beaver, J.D.; Muhammed, K.; Croese, C.; Bell, G.; Durighel, G.; Hughes, E.; Waldman, A.D.; Frost, G.; et al. Fasting Biases Brain Reward Systems towards High-Calorie Foods. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidenko, O.; Bonny, J.-M.; Morrot, G.; Jean, B.; Claise, B.; Benmoussa, A.; Fromentin, G.; Tomé, D.; Nadkarni, N.; Darcel, N. Differences in BOLD Responses in Brain Reward Network Reflect the Tendency to Assimilate a Surprising Flavor Stimulus to an Expected Stimulus. Neuroimage 2018, 183, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giel, K.E.; Friederich, H.-C.; Teufel, M.; Hautzinger, M.; Enck, P.; Zipfel, S. Attentional Processing of Food Pictures in Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa—An Eye-Tracking Study. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, Y.; Ramesh, R.N.; Burgess, C.R.; Levandowski, K.M.; Madara, J.C.; Fenselau, H.; Goldey, G.J.; Diaz, V.E.; Jikomes, N.; Resch, J.M. Homeostatic Circuits Selectively Gate Food Cue Responses in Insular Cortex. Nature 2017, 546, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Cross, L.; O’Doherty, J.P. Elucidating the Underlying Components of Food Valuation in the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, L.T.; Borgland, S.L. The Orbitofrontal Cortex, Food Intake and Obesity. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020, 45, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group the PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Prism. Statement BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar]

- Aviram-friedman, R.; Astbury, N.; Ochner, C.N.; Contento, I. Physiology & Behavior Neurobiological Evidence for Attention Bias to Food, Emotional Dysregulation, Disinhibition and de Fi Cient Somatosensory Awareness in Obesity with Binge Eating Disorder. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 184, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, I.; King, J.A.; Bernardoni, F.; Geisler, D.; Seidel, M.; Ritschel, F.; Goschke, T.; Haynes, J.-D.; Roessner, V.; Ehrlich, S. Subliminal and Supraliminal Processing of Reward-Related Stimuli in Anorexia Nervosa. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.J.; ODaly, O.G.; Uher, R.; Friederich, H.-C.; Giampietro, V.; Brammer, M.; Williams, S.C.R.; Schiöth, H.B.; Treasure, J.; Campbell, I.C. Differential Neural Responses to Food Images in Women with Bulimia versus Anorexia Nervosa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.J.; O’Daly, O.; Uher, R.; Friederich, H.-C.; Giampietro, V.; Brammer, M.; Williams, S.C.R.; Schiöth, H.B.; Treasure, J.; Campbell, I.C. Thinking about Eating Food Activates Visual Cortex with Reduced Bilateral Cerebellar Activation in Females with Anorexia Nervosa: An fMRI Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Navarrete, J.J.; Alcauter-Solórzano, S.; Miguel-Bueno, C.; Gonzalez-Olvera, J.J.; Carrillo-Mezo, R.; De Lourdes Martínez-Gudiño, M.; De Jesús Caballero-Romo, A. Neurofunctional Areas Related to Food Appetency in Anorexia Nervosa. J. Psychol. Res. 2012, 5, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, A.; Tkach, J.; Ho, A.; Kennedy, J. Greater Corticolimbic Activation to High-Calorie Food Cues after Eating in Obese vs. Normal-Weight Adults. Appetite 2012, 58, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, C.M.; O’Neill, B.; Beaver, J.; Makwana, A.; Bani, M.; Merlo-Pich, E.; Fletcher, P.C.; Koch, A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Nathan, P.J. Effect of the Dopamine D 3 Receptor Antagonist GSK598809 on Brain Responses to Rewarding Food Images in Overweight and Obese Binge Eaters. Appetite 2012, 59, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, B.; Williams, M.; Touyz, S.; Madden, S.; Kohn, M.; Clark, S.; Caterson, I.; Russell, J. Neural Response to Low Energy and High Energy Foods in Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder: A Functional MRI Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 687849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geliebter, A.; Ladell, T.; Logan, M.; Schweider, T.; Sharafi, M.; Hirsch, J. Responsivity to Food Stimuli in Obese and Lean Binge Eaters Using Functional MRI. Appetite 2006, 46, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizewski, E.R.; Rosenberger, C.; de Greiff, A.; Moll, A.; Senf, W.; Wanke, I.; Forsting, M.; Herpertz, S. Influence of Satiety and Subjective Valence Rating on Cerebral Activation Patterns in Response to Visual Stimulation with High-Calorie Stimuli among Restrictive Anorectic and Control Women. Neuropsychobiology 2010, 62, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göller, S.; Nickel, K.; Horster, I.; Endres, D.; Zeeck, A.; Domschke, K.; Lahmann, C.; Van Elst, L.T.; Maier, S.; Joos, A.A.B. State or Trait: The Neurobiology of Anorexia Nervosa-Contributions of a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsen, L.M.; Lawson, E.A.; Blum, J.; Ko, E.; Makris, N.; Fazeli, P.K.; Klibanski, A.; Goldstein, J.M. Food Motivation Circuitry Hypoactivation Related to Hedonic and Nonhedonic Aspects of Hunger and Satiety in Women with Active Anorexia Nervosa and Weight-Restored Women with Anorexia Nervosa. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012, 37, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horndasch, S.; Roesch, J.; Forster, C.; Doerfler, A.; Lindsiepe, S.; Heinrich, H.; Graap, H.; Moll, G.H.; Kratz, O. Neural Processing of Food and Emotional Stimuli in Adolescent and Adult Anorexia Nervosa Patients. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, A.A.B.; Saum, B.; Tebartz, L.; Elst, V.; Perlov, E.; Glauche, V.; Hartmann, A.; Freyer, T.; Tüscher, O.; Zeeck, A. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging Amygdala Hyperreactivity in Restrictive Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2011, 191, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, A.A.B.; Saum, B.; Zeeck, A.; Perlov, E.; Glauche, V.; Hartmann, A.; Freyer, T.; Sandholz, A.; Unterbrink, T.; Van Elst, L.T.; et al. Frontocingular Dysfunction in Bulimia Nervosa When Confronted with Disease-Specific Stimuli. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.R.; Ku, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Jung, Y.-C. Functional and Effective Connectivity of Anterior Insula in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 521, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, E.A.; Holsen, L.M.; Santin, M.; Meenaghan, E.; Eddy, K.T.; Becker, A.E.; Herzog, D.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; Klibanski, A. Oxytocin Secretion Is Associated with Severity of Disordered Eating Psychopathology and Insular Cortex Hypoactivation in Anorexia Nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E1898–E1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, J.E.; Namkoong, K.; Jung, Y.-C. Impaired Prefrontal Cognitive Control over Interference by Food Images in Binge-Eating Disorder and Bulimia Nervosa. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 651, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, Y.; Buchwald, C.; Georgiewa, P.; Bohner, G.; Bauknecht, H.-C.; Ballmaier, M.; Klapp, B.F.; Klingebiel, R. Compulsivity Predicts Fronto Striatal Activation in Severely Anorectic Individuals. Neuroscience 2011, 197, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuroscience, B.; Sanders, N.; Smeets, P.A.M.; Van Elburg, A.A.; Danner, U.N.; Van Meer, F.; Hoek, H.W.; Adan, R.A.H. Altered Food-Cue Processing in Chronically Ill and Recovered Women with Anorexia Nervosa. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santel, S.; Baving, L.; Krauel, K.; Muente, T.F.; Rotte, M. Hunger and Satiety in Anorexia Nervosa: FMRI during Cognitive Processing of Food Pictures. Brain Res. 2006, 1114, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaife, J.C.; Godier, L.R.; Reinecke, A.; Harmer, C.J.; Park, R.J. Differential Activation of the Frontal Pole to High vs Low Calorie Foods: The Neural Basis of Food Preference in Anorexia Nervosa? Psychiatry Res. 2016, 258, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schienle, A.; Schaefer, A.; Hermann, A.; Vaitl, D. Binge-Eating Disorder: Reward Sensitivity and Brain Activation to Images of Food. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultson, H.; Van Meer, F.; Sanders, N.; Van Elburg, A.A.; Danner, U.N.; Hoek, H.W.; Adan, R.A.H.; Smeets, P.A.M. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging Associations between Neural Correlates of Visual Stimulus Processing and Set-Shifting in Ill and Recovered Women with Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2016, 255, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, R.; Brammer, M.J.; Murphy, T.; Campbell, I.C.; Ng, V.W.; Williams, S.C.R.; Treasure, J. Recovery and Chronicity in Anorexia Nervosa: Brain Activity Associated with Differential Outcomes. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, R.; Murphy, T.; Brammer, M.J.; Dalgleish, T.; Phillips, M.L.; Ng, V.W.; Andrew, C.M.; Williams, S.C.; Campbell, I.C.; Treasure, J. Medial Prefrontal Cortex Activity Associated with Symptom Provocation in Eating Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eynde, F.; Giampietro, V.; Simmons, A.; Uher, R.; Andrew, C.M.; Harvey, P.; Campbell, I.C.; Schmidt, U. Brain Responses to Body Image Stimuli but Not Food Are Altered in Women with Bulimia Nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonderlich, J.A.; Breithaupt, L.E.; Crosby, R.D.; Thompson, J.C.; Engel, S.G.; Fischer, S. The Relation between Craving and Binge Eating: Integrating Neuroimaging and Ecological Momentary Assessment. Appetite 2017, 117, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S.; Rennalls, S.J.; Leppanen, J.; Mataix-cols, D.; Simmons, A.; Suda, M.; Campbell, I.C.; Daly, O.O.; Cardi, V. Journal of A Ff Ective Disorders Exposure to Food in Anorexia Nervosa and Brain Correlates of Food-Related Anxiety: Fi Ndings from a Pilot Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, A.; O’Donnell, J.M.; Ofei-Tenkorang, N.; Meisman, A.R.; Nash, J.K.; Mitan, L.P.; DiFrancesco, M.; Altaye, M.; Gordon, C.M. Correlation of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Response to Visual Food Stimuli With Clinical Measures in Adolescents With Restrictive Eating Disorders. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Horvath, T.L. Neurobiology of Feeding and Energy Expenditure. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 30, 367–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Young, A.D.; Femia, L.A.; Bogorodzki, P.; Rogowska, J.; Yurgelun-Todd, D.A. Cortical and Limbic Activation during Viewing of High- versus Low-Calorie Foods. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, R.; Sjödén, P.O. A Functional Analysis of Food Habits. Scand. J. Nutr. 1992, 36, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls, B.J. Do Chemosensory Changes Influence Food Intake in the Elderly? Physiol. Behav. 1999, 66, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.C.; Petrovich, G.D. A Neural Systems Analysis of the Potentiation of Feeding by Conditioned Stimuli. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 86, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowdrey, F.A.; Park, R.J.; Harmer, C.J.; McCabe, C. Increased Neural Processing of Rewarding and Aversive Food Stimuli in Recovered Anorexia Nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Barbarich-Marsteller, N.C.; Frank, G.K.; Bailer, U.F.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Crosby, R.D.; Henry, S.E.; Vogel, V.; Plotnicov, K.; McConaha, C. Personality Traits after Recovery from Eating Disorders: Do Subtypes Differ? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006, 39, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führer, D.; Zysset, S.; Stumvoll, M. Brain Activity in Hunger and Satiety: An Exploratory Visually Stimulated FMRI Study. Obesity 2008, 16, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.M.; Pollatos, O. The Relevance of Interoception for Eating Behavior and Eating Disorders. Interoceptive Mind Homeost. Aware. 2018, 4, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. The Role of the Dorsal Striatum in Choice Impulsivity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1451, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.J.; Stopyra, M.A.; Friederich, H.-C. Neural Processing of Disorder-Related Stimuli in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa: A Narrative Review of Brain Imaging Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.; Wiseman, C.V.; Sunday, S.R.; Klapper, F.; Alkalay, L.; Halmi, K.A. Neurocognitive Evidence Favors “Top down” over “Bottom up” Mechanisms in the Pathogenesis of Body Size Distortions in Anorexia Nervosa. Eat. Weight Disord. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2001, 6, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civilotti, C.; Franceschinis, M.; Gandino, G.; Veglia, F.; Anselmetti, S.; Bertelli, S.; Agostino, A.D.; Redaelli, C.A.; Del Giudice, R.; Giampaolo, R.; et al. State of Mind Assessment in Relation to Adult Attachment and Text Analysis of Adult Attachment Interviews in a Sample of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 1760–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlén, M. What Constitutes the Prefrontal Cortex? Science 2017, 358, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parto Dezfouli, M.; Zarei, M.; Constantinidis, C.; Daliri, M.R. Task-Specific Modulation of PFC Activity for Matching-Rule Governed Decision-Making. Brain Struct. Funct. 2021, 226, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gaal, S.; Lamme, V.A.F. Unconscious High-Level Information Processing: Implication for Neurobiological Theories of Consciousness. Neuroscience 2012, 18, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.G.; Vacca, G.; Ahn, S. A Top-down Perspective on Dopamine, Motivation and Memory. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008, 90, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarter, M.; Givens, B.; Bruno, J.P. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Sustained Attention: Where Top-down Meets Bottom-Up. Brain Res. Rev. 2001, 35, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kloet, E.R.; de Kloet, S.F.; de Kloet, C.S.; de Kloet, A.D. Top-down and Bottom-up Control of Stress-coping. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 31, e12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Gothelf, A.; Leor, S.; Apter, A.; Fennig, S. The Impact of Comorbid Depressive and Anxiety Disorders on Severity of Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescent Girls. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.E.; Crow, S. Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2006, 19, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, W.H.; Bulik, C.M.; Thornton, L.; Barbarich, N.; Masters, K.; Group, P.F.C. Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders with Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2215–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, H. The Golden Cage: The Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa; Cambridge USA Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 0674005848. [Google Scholar]

- Jäncke, L.; Mirzazade, S.; Shah, N.J. Attention Modulates Activity in the Primary and the Secondary Auditory Cortex: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study in Human Subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 266, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaley, A.; Cooney, J.W.; Rissman, J.; D’esposito, M. Top-down Suppression Deficit Underlies Working Memory Impairment in Normal Aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1298–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbo, M.; Zaccagnino, M.; Cussino, M.; Civilotti, C. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2017, 14, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Civilotti, C.; Cussino, M.; Callerame, C.; Fernandez, I.; Zaccagnino, M. Changing the Adult State of Mind With Respect to Attachment: An Exploratory Study of the Role of EMDR Psychotherapy. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2019, 13, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slof-Op’t Landt, M.C.T.; Dingemans, A.E.; Giltay, E.J. Eating Disorder Psychopathology Dimensions Based on Individual Co-Occurrence Patterns of Symptoms over Time: A Dynamic Time Warp Analysis in a Large Naturalistic Patient Cohort. Eat. Weight Disord. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 3649–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.R.; Freeman, C.P.; Munro, J. Impulsivity and Dyscontrol in Bulimia Nervosa: Is Impulsivity an Independent Phenomenon or a Marker of Severity? Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1993, 87, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Smith, G.T.; Anderson, K.G. Clarifying the Role of Impulsivity in Bulimia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 33, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Testa, G.; Lozano-Madrid, M.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Granero, R.; Perales, J.C.; Navas, J.F.; Megías-Robles, A. Emotional and Non-emotional Facets of Impulsivity in Eating Disorders: From Anorexia Nervosa to Bulimic Spectrum Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnis, A.; Celeghin, A.; Diano, M.; Mendez, C.A.; Spadaro, G.; Mosso, C.O.; Avenanti, A.; Tamietto, M. Functional Neuroanatomy of Racial Categorization from Visual Perception: A Meta-Analytic Study. Neuroimage 2020, 217, 116939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Chun, J.-W.; Park, C.-H.; Cho, H.; Choi, J.; Yang, S.; Ahn, K.-J.; Kim, D.J. The Correlation between the Frontostriatal Network and Impulsivity in Internet Gaming Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, D.; Enewoldsen, N.; Weisel, K.K.; Saur, S.; Fuhrmann, L.; Lang, C.; Berking, M.; Zink, M.; Ahnert, A.; Falkai, P. Lower Emotion Regulation Competencies Mediate the Association between Impulsivity and Craving during Alcohol Withdrawal Treatment. Subst. Use Misuse 2022, 57, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Song, Z.; Tian, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhu, C.; Ji, G.; Luo, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Mao, Y. Basolateral Amygdala Input to the Medial Prefrontal Cortex Controls Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder-like Checking Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3799–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.G.; Corneliussen, S.J.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Crosby, R.D.; Le Grange, D.; Crow, S.; Klein, M.; Bardone-Cone, A.; Peterson, C.; Joiner, T. Impulsivity and Compulsivity in Bulimia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 38, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Gregertsen, E.C.; Hindocha, C.; Serpell, L. Impulsivity and Compulsivity in Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ranson, K.M.; Kaye, W.H.; Weltzin, T.E.; Rao, R.; Matsunaga, H. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms before and after Recovery from Bulimia Nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanzhula, I.A.; Kinkel-Ram, S.S.; Levinson, C.A. Perfectionism and Difficulty Controlling Thoughts Bridge Eating Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms: A Network Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, M.; Lambert, E.; Treasure, J. Towards a Translational Approach to Food Addiction: Implications for Bulimia Nervosa. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2019, 6, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, M.; Rousselet, M.; Brunault, P.; Thiabaud, E.; Lambert, S.; Rocher, B.; Challet-Bouju, G.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Food Addiction among Female Patients Seeking Treatment for an Eating Disorder: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L.; Le Grange, D. Bulimia Nervosa in Adolescents: Prevalence and Treatment Challenges. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2018, 9, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.G.; Robbins, T.W. The Neurobiological Underpinnings of Obesity and Binge Eating: A Rationale for Adopting the Food Addiction Model. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáuregui-Lobera, I.; Montes-Martínez, M. Emotional Eating and Obesity. In Psychosomatic Medicine; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 1839682337. [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg, M.J.; Steiger, H.; Gauvin, L.; Wonderlich, S.A. Binge Antecedents in Bulimic Syndromes: An Examination of Dissociation and Negative Affect. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007, 40, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Mela, C.; Maglietta, M.; Castellini, G.; Amoroso, L.; Lucarelli, S. Dissociation in Eating Disorders: Relationship between Dissociative Experiences and Binge-Eating Episodes. Compr. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, J.M.; Zirkel, S. Dissociation in the Binge–Purge Cycle of Bulimia Nervosa. J. Trauma Dissociation 2008, 9, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.W.; Frewen, P.A.; van der Kolk, B.A.; Lanius, R.A. Neural Correlates of Reexperiencing, Avoidance, and Dissociation in PTSD: Symptom Dimensions and Emotion Dysregulation in Responses to Script-driven Trauma Imagery. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzinga, B.M.; Ardon, A.M.; Heijnis, M.K.; De Ruiter, M.B.; Van Dyck, R.; Veltman, D.J. Neural Correlates of Enhanced Working-Memory Performance in Dissociative Disorder: A Functional MRI Study. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roydeva, M.I.; Reinders, A.A.T.S. Biomarkers of Pathological Dissociation: A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 123, 120–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, E.; Gray, K.; Miller, G.; Tyler, R.; Wiers, C.E.; Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J. Food Addiction: A Common Neurobiological Mechanism with Drug Abuse. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Ikuta, T. Caudate-Precuneus Functional Connectivity Is Associated with Obesity Preventive Eating Tendency. Brain Connect. 2017, 7, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Mussap, A.J. The Relationship between Dissociation and Binge Eating. J. Trauma Dissociation 2008, 9, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Authors | Date | Eating Disorder | Patients Group (Mean Age or Range) | Healthy Group (Mean Age or Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aviram-Friedman et al. [66] | 2018 | BED | 13 BED (18–65) | 28 (18–65) |

| 2 | Boehm et al. [67] | 2018 | AN | 35 AN (12–29) | 35 (12–29) |

| 3 | Brooks et al. [68] | 2011 | BN AN | 8 BN (16–50) 42 AN (16–50) | 24 (16–50) |

| 4 | Brooks et al. [69] | 2012 | AN | 18 AN (16–50) | 24 (16–50) |

| 5 | Cervantes-Navarrete et al. [70] | 2012 | AN | 5 AN (19–24) | 5 |

| 6 | Dimitropoulos et al. [71] | 2012 | BED | 22 BED (24.8) | 16 (24.6) |

| 7 | Dodds et al. [72] | 2012 | BED | 26 BED (35.1; 15 M) | / |

| 8 | Donnelly et al. [73] | 2022 | BN BED | 14 BN (26.63) 5 BE (26.63) | 19 (21.74) |

| 9 | Geliebter et al. [74] | 2006 | BED | 10 BED (29–41) | 10 (20–24) |

| 10 | Gizewski et al. [75] | 2010 | AN | 12 AN (18–52) | 12 (21–35) |

| 11 | Göller et al. [76] | 2022 | AN ANrec | 31 AN (24.1) 18 ANrec (27.4) | 27 (23.6) |

| 12 | Holsen et al. [77] | 2012 | AN, ANrec | 12 AN (21.8) 10 ANrec (23.4) | 11 (21.6) |

| 13 | Horndash et al. [78] | 2018 | AN young AN adult | 15 AN young (16.41) 16 AN adult (26.71) | 18 young (15.95) 16 adult (16.88) |

| 14 | Joos et al. [79] | 2011 | AN | 11 AN (25) | 11 (26) |

| 15 | Joos et al. [80] | 2011 | BN | 13 BN (25.2) | 13 (27) |

| 16 | Kim et al. [81] | 2012 | AN BN | 18 AN (25.2) 20 BN (22.9) | 20 (23.3) |

| 17 | Lawson et al. [82] | 2012 | AN ANrec | 13 AN (18–28) 9 AN rec (18–28) | 13 (18–28) |

| 18 | Lee et al. [83] | 2017 | BN BED | 12 BN (23.7) 13 BED (23.6) | 14 (23.2) |

| 19 | Rothemund et al. [84] | 2011 | AN | 12 AN (24) | 12 (26) |

| 20 | Sanders et al. [85] | 2015 | AN ANrec | 15 AN (25.6) 15 ANrec (24.3) | 15 (25,8) |

| 21 | Santel et al. [86] | 2006 | AN | 13 AN (16.1) | 10 (16.8) |

| 22 | Scaife et al. [87] | 2016 | AN | 12 AN (18–60) 14 ANrec (18–60) | 16 (18–60) |

| 23 | Schienle et al. [88] | 2009 | BN BED | 14 BN (23.1) 17 BED (26.4) | 36 (23.65) |

| 24 | Sultson et al. [89] | 2016 | AN ANrec | 14 AN (25.57) 14 ANrec (24.79) | 15 (25.8) |

| 25 | Uher et al. [90] | 2003 | AN ANrec | 8 AN (25.6) 9 ANrec (26.9) | 9 (26.6) |

| 26 | Uher et al. [91] | 2004 | AN BN | 16 AN (26.93) 10 BN (29.8) | 19 (26.68) |

| 27 | Van den Eynde et al. [92] | 2013 | BN | 21 BN (28) | 23 (27.3) |

| 28 | Wonderlich et al. [93] | 2017 | BN | 16 BN (22.85) | / |

| 29 | Young et al. [94] | 2020 | AN | 16 AN (31.4) | 20 (26.7) |

| 30 | Ziv et al. [95] | 2020 | AN | 18 AN (16.2) | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Celeghin, A.; Palermo, S.; Giampaolo, R.; Di Fini, G.; Gandino, G.; Civilotti, C. Brain Correlates of Eating Disorders in Response to Food Visual Stimuli: A Systematic Narrative Review of FMRI Studies. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030465

Celeghin A, Palermo S, Giampaolo R, Di Fini G, Gandino G, Civilotti C. Brain Correlates of Eating Disorders in Response to Food Visual Stimuli: A Systematic Narrative Review of FMRI Studies. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(3):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030465

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeleghin, Alessia, Sara Palermo, Rebecca Giampaolo, Giulia Di Fini, Gabriella Gandino, and Cristina Civilotti. 2023. "Brain Correlates of Eating Disorders in Response to Food Visual Stimuli: A Systematic Narrative Review of FMRI Studies" Brain Sciences 13, no. 3: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030465

APA StyleCeleghin, A., Palermo, S., Giampaolo, R., Di Fini, G., Gandino, G., & Civilotti, C. (2023). Brain Correlates of Eating Disorders in Response to Food Visual Stimuli: A Systematic Narrative Review of FMRI Studies. Brain Sciences, 13(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030465