Using Hybrid Telepractice for Supporting Parents of Children with ASD during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Feasibility Study in Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Telepractice

1.2. Supporting Families in Iran

1.3. Country Profile

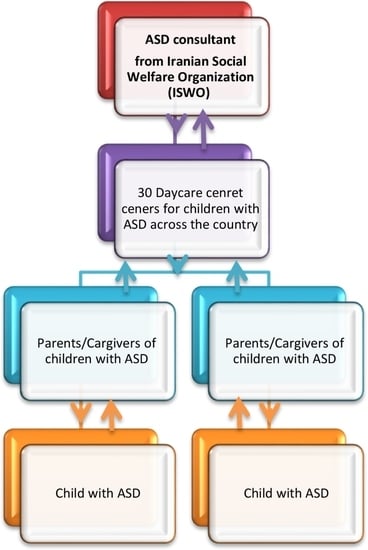

1.4. Developing a Hybrid Telepractice for Families

- Is telepractice a feasible approach for providing services to family caregivers and children with ASD in a less affluent country such as Iran?

- What are the factors that contribute to caregivers’ positive attitudes regarding the telepractice services provided to them and their children with ASD, in the absence of in-person daycare center services?

- Is it possible to increase the effectiveness of telepractice services for caregivers of children with ASD?

2. Methods

2.1. Setting up the Telepractice Service

- Suitable resource materials from Iran—written and visual—were identified to act as a guide for center staff, as well as for sharing with caregivers as appropriate.

- Each participating center nominated a key person as the main coordinator of the center’s telepractice. In most instances, this was a person with the required qualification to supervise the daycare center’s daily services. During the lockdown, other center staff were involved with caregivers and children on a scheduled daily basis for routine contact, but the key person’s responsibility was the coordination, supervision, and monitoring of the prepared online telepractice program.

- An online group was created for the course supervisor and daycare center staff for them to develop procedures relating to freeing up time from other clinical work; making different reading materials accessible for parents, the provision of high-quality supervision and training, establishing peer-learning working groups and planning periodic evaluation of the program.

- Identifying and creating video-based parental training materials for use alongside written materials. Videos are reported to be more effective [29].

- Caregivers needed to have smartphones or similar devices with home internet access and the freeware program, WhatsApp version 4.0.0 (Mountain View, California, 2009), with the free calling feature. This app was also used for documents and link sharing, online video calls, observing the home session, and coaching the parent.

2.1.1. The Main Aims of the Telepractice Service

- To devise individual learning plans for a child with ASD in conjunction with caregivers to use at home.

- To boost the confidence of caregivers in managing their child with ASD at home.

- To answer caregivers’ questions through the provision of accurate personalized information.

- To provide updated information relating to ASD.

2.1.2. Implementing the Telepractice Service

2.1.3. Evaluating Telepractice

- 1.

- What is the most important advantage of the online training course?

- 2.

- What is the most obvious shortcoming of the online training course?

- 3.

- If you have to continue using online courses for a long time, what are your recommendations for improvement of the quality of the course?

- 4.

- Which part of the information was most useful for you?

- 5.

- Which part was less useful for you?

- 6.

- Do you have any further comments about the course?

2.2. Participants

Key Persons

2.3. Activity Records

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Findings

3.2. Quantitative Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herschell, A.D.; McNeil, C.B.; McNeil, D.W. Clinical child psychology’s progress in disseminating empirically supported treatments. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-Lewis, H.; Kershaw, T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.R.; Lygidakis, C.; Neupane, D.; Gyawali, B.; Uwizihiwe, J.P.; Virani, S.S.; Kallestrup, P.; Miranda, J.J. Combating non-communicable diseases: Potentials and challenges for community health workers in a digital age, a narrative review of the literature. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camden, C.; Pratte, G.; Fallon, F.; Couture, M.; Berbari, J.; Tousignant, M. Diversity of practices in telerehabilitation for children with disabilities and effective intervention characteristics: Results from a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismara, L.A.; McCormick, C.E.B.; Wagner, A.L.; Monlux, K.; Nadhan, A.; Young, G.S. Telehealth parent training in the early start Denver model: Results from a randomized controlled study. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2016, 33, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narzisi, A. Phase 2 and Later of COVID-19 Lockdown: Is it possible to perform remote diagnosis and intervention for autism spectrum disorder? An online-mediated approach. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, D.; Cordier, R.; Vaz, S.; Lee, H. Parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely for children with autism spectrum disorder living outside of urban areas: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes-Gillan, S.; Lincoln, M. Parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has preliminary evidence for parent intervention fidelity and improving parent knowledge and children’s social behaviour and communication skills. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2018, 65, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConachie, H.; Diggle, T. Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2007, 13, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, M.; Lang, R.; Andrianopoulos, M.; Boscardin, M.L. Telepractice in the assessment and treatment of individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2010, 13, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.; Trembath, D.; Roberts, J. Telehealth and autism: A systematic search and review of the literature. Int. J. Speech-Language Pathol. 2018, 20, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudding, C. Reimbursement and telepractice. Perspect. Telepractice 2013, 3, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.A.; McConkey, R. Autism in developing countries: Lessons from Iran. Autism Res. Treat. 2011, 2011, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadi, S.A.; McConkey, R.; Kelly, G. Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2013, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.A.; McConkey, R.; Bunting, B. Parental wellbeing of Iranian families with children who have developmental disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.A.; Mahmoodizadeh, A. Omid early intervention resource kit for children with autism spectrum disorders and their families. Early Child Dev. Care 2013, 184, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.A.; Mahmoodizadeh, A. Parents’ reports of their involvement in an Iranian parent-based early intervention programme for children with ASD. Early Child Dev. Care 2013, 183, 1720–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19: Vulnerable and High Risk Groups. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/high-risk-groups (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- UNESCO. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 5 April 2020.).

- Samadi, S.A.; Mahmoodizadeh, A.; McConkey, R. A national study of the prevalence of autism among five-year-old children in Iran. Autism 2011, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, H.; Harrison, G.G.; Mohammad, K. An accelerated nutrition transition in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanparast, S.; Baum, F.; LaBonte, R.; Sanders, D. Community health workers’ Perspectives on their contribution to rural health and well-being in Iran. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelvanovska, N.; Rogy, M.; Rossotto, C.M. Broadband Networks in the Middle East and North Africa: Accelerating High-Speed Internet Access; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanzadeh, D.; Saeednia, H.R. Examining telegram users’ motivations, technical characteristics, trust, attitudes, and positive word-of-mouth: Evidence from Iran. Int. J. Electron. Mark. Retail. 2018, 9, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.; Shahabi, S.; Lankarani, K.B.; Kamali, M.; Mojgani, P. COVID-19 and disabled people: Perspectives from Iran. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, L.A.; Young, G.S.; Stahmer, A.C.; Griffith, E.M.; Rogers, S.J. Dissemination of evidence-based practice: Can we train therapists from a distance? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1636–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorpita, B.F. Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii empirical basis to services task force. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2002, 9, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, H.; Jayanthi, K.; Prabavathy, S.; Renuka, K.; Bhargavan, R. Effectiveness of video assisted teaching on knowledge, attitude and practice among primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Adv. Autism 2019, 5, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaspohler, P.D.; Meehan, C.; Maras, M.A.; Keller, K.E. Ready, willing, and able: Developing a support system to promote implementation of school-based prevention programs. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, K.E.; Wainer, A.L.; Bailey, K.M.; Ingersoll, B.R. A mixed-method evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth-based parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2016, 20, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, S.A.; Nouparst, Z.; Mohammad, M.P.; Ghanimi, F.; McConkey, R. An Evaluation of a training course on autism spectrum disorders (ASD) for care centre personnel in Iran. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2018, 67, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkaia, A.; Stokes, T.F.; Mikiashvili, T. Intercontinental telehealth coaching of therapists to improve verbalizations by children with autism. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2017, 50, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, E.G.; Stainbrook, J.A.; Staubitz, J.E.; Weitlauf, A.S.; Juárez, A.P. The promise of telepractice to address functional and behavioral needs of persons with autism spectrum disorder. In International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities; Hodapp, R.M., Fidler, D.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 235–295. [Google Scholar]

- Coolican, J.; Smith, I.M.; Bryson, S.E. Brief parent training in pivotal response treatment for preschoolers with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, F.; Almalki, N. Parents’ perceptions of early interventions and related services for children with autism spectrum disorder in Saudi Arabia. Int. Educ. Stud. 2016, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, J.; Wolfe, A.; Burke, B.L.; Hepburn, S.; Lindgren, S.; Coury, D. A systematic review of telemedicine in autism spectrum disorders. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 3, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainer, A.L.; Ingersoll, B. Disseminating ASD interventions: A pilot study of a distance learning program for parents and professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 43, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, S.; Marciscano, I.; Holcomb, M.; Erps, K.A.; Major, J.; Lopez, A.M.; Barker, G.P.; Weinstein, R.S. Testing a top-down strategy for establishing a sustainable telemedicine program in a developing country: The Arizona telemedicine program–U.S. Army–Republic of Panama initiative. Telemed. e-Health 2013, 19, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male 5 (17%) |

| Female 25 (83%) | |

| Age | Mean (37.10) SD (6.32) |

| (Min 25 Max 55,) | |

| Education | Undergraduate 5 (17%) |

| Graduate 22 (73%) | |

| Postgraduate 3 (10%) | |

| Profession | Psychologist 19 (63%) |

| Occupational Therapist 5 (18%) | |

| Speech and Language Therapist 2 (7%) | |

| Educational Science 3 (10%) | |

| General Health 1 (3%) | |

| Experience with ASD in years | Mean (8.26) SD (3.23) |

| (Min 1, Max 15) |

| Variable | Completed Course Group | Drop Out Group |

|---|---|---|

| N = 336 | N = 81 | |

| Relationship with the child with ASD | Mother: 279 (83%) | Mother: 57 (70%) |

| Father: 17 (5%) | Father: 12 (15%) | |

| Sibling: 9 (3%) | Sibling: 4 (5%) | |

| Grandparent: 1 (0.3%) | Grandparent: (−%) | |

| Both Parents: 30 (9%) | Both Parents: 8(10%) | |

| Caregivers age | Mean (35.79) SD (6.51) | Mean (37.88) SD (6.87) |

| (Max 70, Min 18) | (Max 56, Min 22) | |

| Caregivers education in years | Under-university education: 210 (62.5%) | Under-university education: 57 (70%) |

| University Education: 126 (37.7%) | University Education: 24 (30%) | |

| Caregivers Profession | Housewife: 216 (64%) | Housewife: 54 (67%) |

| Public work: 60 (18%) | Public work: 14 (17%) | |

| Technician: 26 (8%) | Technician: 6 (7%) | |

| Education: 16 (5%) | Education: 3 (4%) | |

| Medical and Health: 14 (4%) | Medical and Health: 4 (5%) | |

| Unemployed: 4 (1%) | Unemployed: (−%) | |

| Having assistance with caregiving from the family members | Yes: 192 (57%) | Yes: 43 (53%) |

| No: 144 (43%) | No: 38(47%) |

| Variable | Completed Course Group | Drop Out Group |

|---|---|---|

| N = 336 | N = 81 | |

| Children’s Age | Mean (8.06) SD (2.78) | Mean (10.81) SD (2.31) |

| (Max 14, Min 3) | (Max 14, Min 3) | |

| Children’s Gender | Boys 261 (78%), Girls 75 (22%) | Boys 60 (74%), Girls 21 (26%) |

| Birth Order | First born: 203 (60%) | First born: 47 (58%) |

| Second born: 102 (30%) | Second born: 29 (38%) | |

| 3rd and above born: 31 (10%) | 3rd and above born: 5 (4%) | |

| Children’s diagnosis | ASD: 158 (55.5%) | ASD: 19 (23.5%) |

| Dual Diagnosis (diagnosis of ASD and other impairments such as Attention Deficit and Hyper Activity (ADHD), Cerebral Palsy (CP), or Intellectual Disability ID): 151 (45%) | Dual Diagnosis: 62 (76.5%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samadi, S.A.; Bakhshalizadeh-Moradi, S.; Khandani, F.; Foladgar, M.; Poursaid-Mohammad, M.; McConkey, R. Using Hybrid Telepractice for Supporting Parents of Children with ASD during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Feasibility Study in Iran. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110892

Samadi SA, Bakhshalizadeh-Moradi S, Khandani F, Foladgar M, Poursaid-Mohammad M, McConkey R. Using Hybrid Telepractice for Supporting Parents of Children with ASD during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Feasibility Study in Iran. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(11):892. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110892

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamadi, Sayyed Ali, Shahnaz Bakhshalizadeh-Moradi, Fatemeh Khandani, Mehdi Foladgar, Maryam Poursaid-Mohammad, and Roy McConkey. 2020. "Using Hybrid Telepractice for Supporting Parents of Children with ASD during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Feasibility Study in Iran" Brain Sciences 10, no. 11: 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110892

APA StyleSamadi, S. A., Bakhshalizadeh-Moradi, S., Khandani, F., Foladgar, M., Poursaid-Mohammad, M., & McConkey, R. (2020). Using Hybrid Telepractice for Supporting Parents of Children with ASD during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Feasibility Study in Iran. Brain Sciences, 10(11), 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110892