Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- To investigate the general emotional tone of dreams and the frequency of specific emotions in dreams through a repertoire of emotions broader than the one mostly used in dream literature;

- (b)

- To assess the associations of dream emotions with emotions of the previous day and previous weeks, as well as possible differences in the intensity and frequency of emotions across the dream and the waking periods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

- (a)

- Italian version of the modified Differential Emotions Scale (see Appendix A): The original modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES [47,48]) consists of 20 items corresponding to 20 different emotion categories (10 positive and 10 negative) whose intensity over the past 24 h is rated on a five-point Likert scale (from 0 = Not at all, to 4 = Extremely). Each category is described by three adjectives (e.g., “Grateful, appreciative or thankful”): for clarity purposes, throughout the manuscript, the noun referring to the first of the three adjectives will be used to identify specific emotion categories (e.g., “Gratefulness”). The scale has been validated on the Greek population [55] and has shown to have good psychometric properties in its various translations [26,56,57]. Fredrickson’s most recent version of the questionnaire [48] has been here translated into Italian and supplemented with two additional positive emotions (“sexual/desiring/flirtatious” and “sympathy/concern/compassion”), which were included in the earlier version of the instrument [47]. This standard version is here labeled WAKE-24hr mDES, in order to distinguish it from the other version of the mDES (WAKE-2wks form), assessing the frequency of each emotion over the past two weeks, which was also developed as part of this study following Fredrickson et al.’s suggestion [48]. Furthermore, a specific version has been created (DREAM mDES) for the evaluation of the intensity of dream emotions: it consists of a WAKE-24hr version of the mDES in which instructions are slightly modified, requiring the participant to refer to the emotions experienced during the last recalled dream rather than the past 24 h. The specific instructions provided in the DREAM and the WAKE-24hr mDES versions are the following: “Please think back to how you have felt during your last recalled dream/last 24 h. Using the 0–4 scale below, indicate the greatest amount that you’ve experienced each of the following feelings.” As for the WAKE-2wks form, the instructions are the following: “Please think back to how you have felt during the past two weeks. Using the 0–4 scale below, indicate the frequency with which you’ve experienced each of the following feelings.” (from 0 = Never, to 4 = Very frequently). Finally, the mDES also allows the use of aggregate measures of positive and negative emotionality (the Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA) subscales, i.e., average scores of the positive and negative emotion items, respectively), which have shown to have high internal reliability, ranging from 0.82 to 0.94 [58,59].

- (b)

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI [54]): This questionnaire assesses sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month time interval. It yields a global score, ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality.

- (c)

- Mannheim Dream Questionnaire (MADRE [53]): This questionnaire measures several variables related to dreams such as frequency of dream recall, nightmares and lucid dreaming, attitude towards dreams and the effects of dreams on waking life. Here we only report data on dream recall frequency, emotional intensity of dreams, affective tone of dreams, and nightmare frequency.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Instrument

3.2. Descriptive Data of the Dream Study

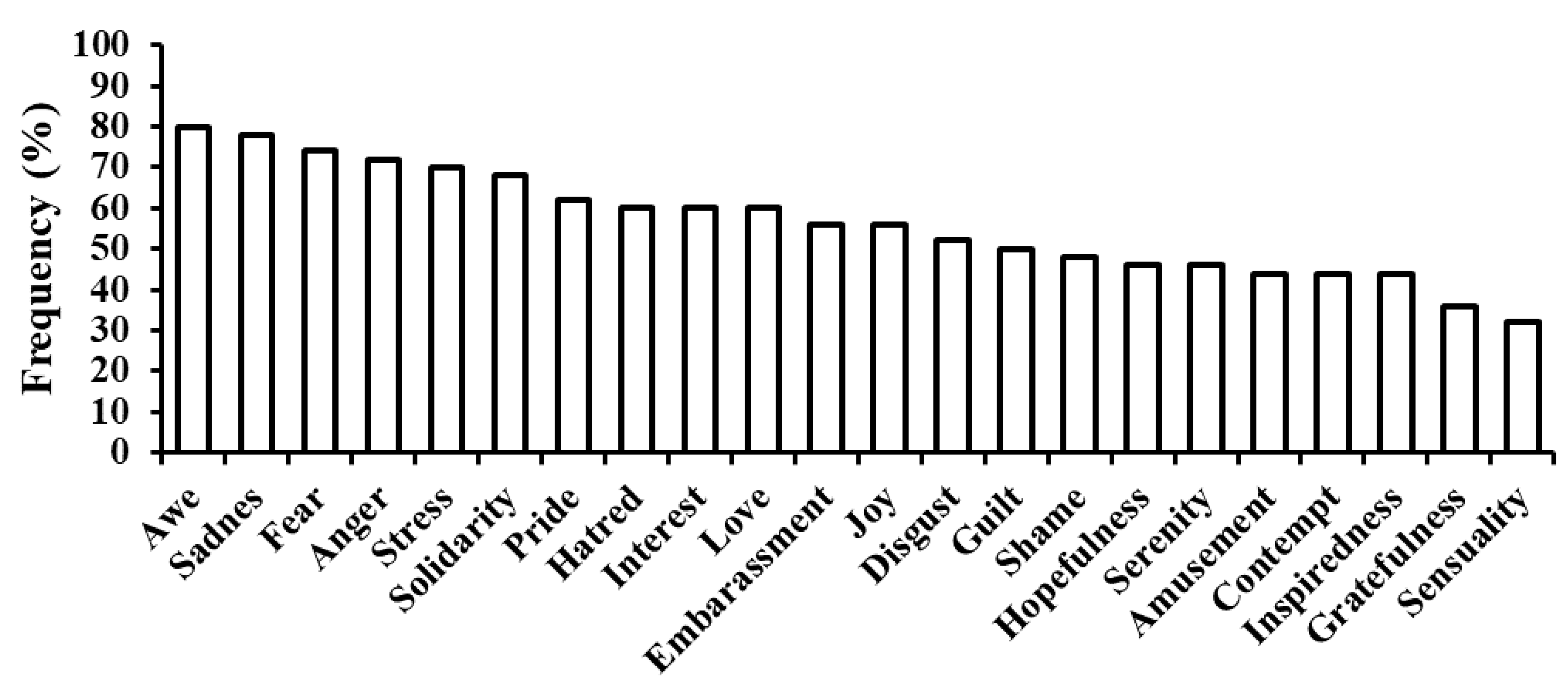

3.3. Characteristics of Dream Emotions

3.4. Differences between WAKE-2wks, WAKE-24hr, and Dream Emotions

3.5. Predictors of Dream Emotions

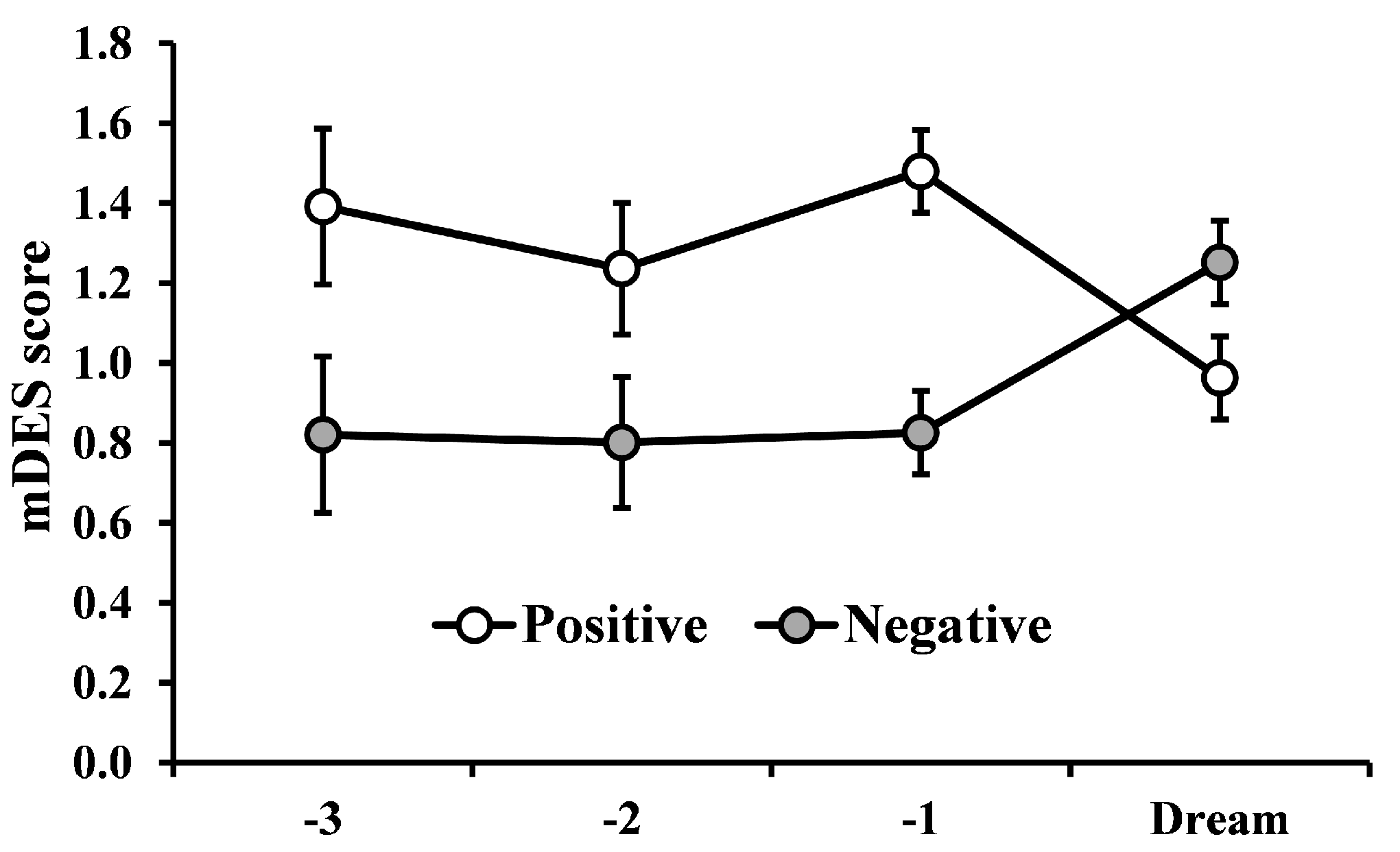

3.6. Lag Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychometric Properties of the mDES and General Observations on the Instrument

4.2. Frequency and Valence of Dream Emotions

4.3. Relationships between Wake and Dream Emotions

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Modified Differential Emotions Scale (MDES)—Dream |

|---|

| Please think back to how you have felt during your last recalled dream. Using the 0–4 scale below, indicate the greatest amount that you’ve experienced each of the following feelings. |

| 0 = Not at all, 1 = A little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = Quite a bit, and 4 = Extremely |

| 1. What is the most amused, fun-loving, or silly you felt? |

| 2. What is the most angry, irritated, or annoyed you felt? |

| 3. What is the most ashamed, humiliated, or disgraced you felt? |

| 4. What is the most awe, wonder, or amazement you felt? |

| 5. What is the most contemptuous, scornful, or disdainful you felt? |

| 6. What is the most disgust, distaste, or revulsion you felt? |

| 7. What is the most embarrassed, self-conscious, or blushing you felt? |

| 8. What is the most grateful, appreciative, or thankful you felt? |

| 9. What is the most guilty, repentant, or blameworthy you felt? |

| 10. What is the most hate, distrust, or suspicion you felt? |

| 11. What is the most hopeful, optimistic, or encouraged you felt? |

| 12. What is the most inspired, uplifted, or elevated you felt? |

| 13. What is the most interested, alert, or curious you felt? |

| 14. What is the most joyful, glad, or happy you felt? |

| 15. What is the most love, closeness, or trust you felt? |

| 16. What is the most proud, confident, or self-assured you felt? |

| 17. What is the most sad, downhearted, or unhappy you felt? |

| 18. What is the most scared, fearful, or afraid you felt? |

| 19. What is the most serene, content, or peaceful you felt? |

| 20. What is the most stressed, nervous, or overwhelmed you felt? |

| 21. What is the most sensual, excited, in mood for flirting you felt? |

| 22. What is the most solidarity, care for the others, compassion you felt? |

References

- Tempesta, D.; Socci, V.; De Gennaro, L.; Ferrara, M. Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 40, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, M.; Wang, Y.L. Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: An intimate relationship. AIMS Neurosci. 2017, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Lombardo, C.; Riemann, D. Sleep and emotions: A focus on insomnia. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove, M.; Cluydts, R. The emotional brain and sleep: An intimate relationship. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquet, P.; Peters, J.; Aerts, J.; Delfiore, G.; Degueldre, C.; Luxen, A.; Franck, G. Functional neuroanatomy of human rapid-eye-movement sleep and dreaming. Nature 1996, 383, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Maquet, P. Sleep imaging and the neuro-psychological assessment of dreams. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2002, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofzinger, E.A.; Mintun, M.A.; Wiseman, M.; Kupfer, D.J.; Moore, R.Y. Forebrain activation in REM sleep: An FDG PET study. Brain Res. 1997, 770, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace-Schott, E.F.; Hobson, J.A. The neurobiology of sleep: Genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.N.; Walker, M.P. The role of sleep in emotional brain function. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Coplan, J.D.; Kent, J.M.; Gorman, J.M. The noradrenergic system in pathological anxiety: A focus on panic with relevance to generalized anxiety and phobias. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schredl, M.; Wittmann, L. Dreaming: A psychological view. Dreaming 2005, 484, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpelli, S.; D’Atri, A.; Gorgoni, M.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. EEG oscillations during sleep and dream recall: State- or trait-like individual differences? Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.P.; van der Helm, E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Nielsen, T. Nightmares, Bad Dreams, and Emotion Dysregulation: A Review and New Neurocognitive Model of Dreaming. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R.; Agargun, M.Y.; Kirkby, J.; Friedman, J.K. Relation of dreams to waking concerns. Psychiatry Res. 2006, 141, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R.; Luten, A.; Young, M.; Mercer, P.; Bears, M. Role of REM sleep and dream affect in overnight mood regulation: A study of normal volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1998, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revonsuo, A. The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 23, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revonsuo, A.; Tuominen, J. The Avatars in the Machine: Dreaming as a Simulation of Social Reality. In Open MIND; Metzinger, T., Windt, J.M., Eds.; MIND Group: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpelli, S.; Bartolacci, C.; D’Atri, A.; Gorgoni, M.; De Gennaro, L. The Functional Role of Dreaming in Emotional Processes. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagrove, M.; Henley-Einion, J.; Barnett, A.; Edwards, D.; Seage, C.H. A replication of the 5–7 day dream-lag effect with comparison of dreams to future events as control for baseline matching. Conscious. Cogn. 2011, 20, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, E.; Eichenlaub, J.; Lewis, P.; Walker, M.; Gaskell, M.; Malinowski, J.; Blagrove, M. The dream-lag effect: Selective processing of personally significant events during Rapid Eye Movement sleep, but not during Slow Wave Sleep. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2015, 122, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenlaub, J.B.; van Rijn, E.; Phelan, M.; Ryder, L.; Gaskell, M.G.; Lewis, P.A.; Walker, M.P.; Blagrove, M. The nature of delayed dream incorporation (‘dream-lag effect’): Personally significant events persist, but not major daily activities or concerns. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson-Daoust, E.; Julien, S.; Beaulieu-Prévost, D.; Zadra, A. Predicting the affective tone of everyday dreams: A prospective study of state and trait variables. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koninck, J.; Koulack, D. Dream content and adaptation to a stressful situation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1975, 84, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, P.; Pesonen, H.; Revonsuo, A. Peace of mind and anxiety in the waking state are related to the affective content of dreams. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, S.; Davidson, J.; Shakespeare-Finch, J. Dream emotions, waking emotions, personality characteristics and well-being – a positive psychology approach. Dreaming 2007, 17, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamis, D.A.; Innamorati, M.; Erbuto, D.; Berardelli, I.; Montebovi, F.; Serafini, G.; Amore, M.; Krakow, B.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M. Nightmares and suicide risk in psychiatric patients: The roles of hopelessness and male depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komasi, S.; Soroush, A.; Khazaie, H.; Zakiei, A.; Saeidi, M. Dreams content and emotional load in cardiac rehabilitation patients and their relation to anxiety and depression. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2018, 21, 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R.; Nielsen, T.A. Disturbed dreaming, posttraumatic stress disorder, and affect distress: A review and neurocognitive model. Psych. Bull. 2007, 133, 482–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, B.; Nanovska, S.; Baglioni, C.; Bier, B.; Cabrera, L.; Diemers, S.; Quellmalz, M.; Siegel, M.; Xeni, I.; Szentkiralyi, A.; et al. Insomnia—Perchance a dream? Results from a NREM/REM sleep awakening study in good sleepers and patients with insomnia. Sleep 2018, 41, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Fireman, G.; Spendlove, S.; Pope, A. The Relative Contribution of Affect Load and Affect Distress as Predictors of Disturbed Dreaming. Behav. Sleep Med. 2011, 9, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schredl, M. Effects of state and trait factors on nightmare frequency. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 253, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagrove, M.; Fisher, S. Trait-state interactions in the etiology of nightmares. Dreaming 2009, 19, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer-Dudek, N.; Shahar, G. Daily stress interacts with trait dissociation to predict sleep-related experiences in young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011, 120, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.A.; Alfano, C.A. Sleep and emotion regulation: An organizing, integrative review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 31, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.S.; Van de Castle, R.L. The Content Analysis of Dreams; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, F. The phenomenology of dreaming. In The Psychodynamic Implications of the Physiological Studies on Dreams; Madow, L., Snow, L., Eds.; Charles S Thomas: Springfield, MO, USA, 1970; pp. 124–151. [Google Scholar]

- Strauch, I.; Meier, B. Search of Dreams: Results of Experimental Dream Research; SUNY Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T.A.; Deslauriers, D.; Baylor, G.W. Emotions in dream and waking event reports. Dreaming 1991, 1, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, J.M.; Stickgold, R.; Pace-Schott, E.; Williams, J.; Hobson, J.A. Emotion Profiles in the Dreams of Men and Women. Conscious. Cogn. 1994, 3, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosse, R.; Stickgold, R.; Hobson, J.A. The mind in REM sleep: Reports of emotional experience. Sleep 2001, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, P.; Valli, K.; Virta, T.; Revonsuo, A. I know how you felt last night, or do I? Self- and external ratings of emotions in REM sleep dreams. Conscious. Cogn. 2014, 25, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, P.; Feilhauer, D.; Valli, K.; Revonsuo, A. How you measure is what you get: Differences in self- and external ratings of emotional experiences in home dreams. Am. J. Psychol. 2017, 130, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-C.C. Emotions before, during, and after dreaming sleep. Dreaming 2007, 17, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, P.; Revonsuo, A.; Noreika, V.; Valli, K. EEG Frontal Alpha Asymmetry and Dream Affect: Alpha Oscillations over the Right Frontal Cortex during REM Sleep and Presleep Wakefulness Predict Anger in REM Sleep Dreams. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 4775–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Tugade, M.M.; Waugh, C.E.; Larkin, G.R. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive Emotions Broaden and Build. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology: Positive Emotions Broaden and Build; Devine, G., Plant, E.A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikka, P.; Revonsuo, A.; Sandman, N.; Tuominen, J.; Valli, K. Dream emotions: A comparison of home dream reports with laboratory early and late REM dream reports. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, B. Translation and cultural adaptation of the survey instruments. Third Int. Math. Sci. Study (TIMSS) Tech. Rep. 1996, 1, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Schredl, M.; Berres, S.; Klingauf, A.; Schellhaas, S.; Göritz, A.S. The Mannheim Dream Questionnaire (MADRE): Retest reliability, age and gender effects. Int. J. Dream Res. 2014, 7, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.L. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M.; Stalikas, A.; Pezirkianidis, C.; Karakasidou, I. Reliability and Validity of the Modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES) in a Greek Sample. Psychology 2016, 7, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, D.; Bobowik, M.; Carrera, P.; Bosco, S. Evaluación de Afectividad durante diferentes episodios emocionales. In Superando la Violencia Colectiva y Construyendo Cultura de paz [Overcoming Collective Violence and Building Culture of Peace]; Páez, D., Martin Beristain, C., González-Castro, J.L., de Rivera, J., Basabe, N., Eds.; Fundamentos: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sahar, N.; Muzaffar, N.M. Role of Family System, Positive Emotions and Resilience in Social Adjustment Among Pakistani Adolescents. JEHCP 2017, 6, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A.; Coffey, K.A.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S.M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M.A.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Brown, S.L.; Mikels, J.A.; Conway, A.M. Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 2009, 9, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schredl, M.; Doll, E. Emotions in diary dreams. Conscious. Cog. 1998, 7, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, T.L.; LaBerge, S. Cognition and metacognition in dreaming and waking: Comparisons of first and third-person ratings. Dreaming 1996, 6, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, T.L.; LaBerge, S.P. Dreaming and waking: Similarities and differences revisited. Conscious. Cog. 2011, 20, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domhoff, G.W. The content of dreams: Methodologia and theoretical implications. In Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th ed.; Kryger, M., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Saunders, W.B.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 522–534. [Google Scholar]

- Zadra, A.; Domhoff, G.W. Dream content: Quantitative findings. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed.; Kryger, M.H., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 515–522. [Google Scholar]

- Ashare, R.L.; Norris, C.J.; Wileyto, E.P.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Strasser, A. Individual differences in positivity offset and negativity bias: Gender-specific associations with two serotonin receptor genes. Pers. Indiv. Diff. 2013, 55, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schredl, M. Dream content analysis: Basic principles. Int. J. Dream Res. 2010, 3, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan, T.L.; Claudatos, S. Phenomenological features of dreams: Results from dream log studies using the Subjective Experiences Rating Scale (SERS). Conscious. Cogn. 2016, 41, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. General Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.; Lortie-Lussier, M.; Mercier, P.; Grenier, J.; De Koninck, J. Emotions in the Diary and REM Dreams of Young and Late Adulthood Women and Their Relation to Life Satisfaction. Dreaming 2005, 15, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussy, F.; Brunette, M.; Mercier, P.; Gonthier, I.; Grenier, J.; SiroisBerliss, M.; Lortie Lussier, M.; De Koninck, J. Daily events and dream content: Unsuccessful matching attempts. Dreaming 2000, 10, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M.; Wenzlaff, R.M.; Kozak, M. Dream rebound: The return of suppressed thoughts in dreams. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, F.; Bryant, R.A. The tendency to suppress, inhibiting thoughts, and dream rebound. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröner-Borowik, T.; Gosch, S.; Hansen, K.; Borowik, B.; Schredl, M.; Steil, R. The effects of suppressing intrusive thoughts on dream content, dream distress and psychological parameters. J. Sleep Res. 2013, 22, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freud, S. The Interpretation of Dreams; Wordsworth: Hertfordshire, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sterpenich, V.; Perogamvros, L.; Tononi, G.; Schwartz, S. Fear in dreams and in wakefulness: Evidence for day/night affective homeostasis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, E.; Woldgabreal, Y.; Guharajan, D.; Day, A.; Kiageri, V.; Ramtahal, N. Social Desirability Bias Against Admitting Anger: Bias in the Test-Taker or Bias in the Test? J. Pers. Assess. 2018, 101, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, C.; Stemmler, G. Substance and Bias in Social Desirability Responding. Pers. Indiv. Diff. 2003, 35, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is Stronger than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.; Loeffler, M. Comparison of dream content of depressed vs non-depressed dreamers. Psychol. Rep. 1992, 70, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geißler, C.; Schredl, M. College students’ erotic dreams: Analysis of content and emotional tone. Sexologies 2020, 29, e11–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agargun, M.Y.; Cartwright, R. REM sleep, dream variables and suicidality in depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 119, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, J.A.; Pace-Schott, E.F.; Stickgold, R. Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 23, 793–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsley, E.J.; Hirota, Y.; Tucker, M.A.; Smith, M.R.; Antrobus, J.S. Circadian and ultradian influences on dreaming: A dual rhythm model. Brain Res. Bull. 2007, 71, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PA | NA | T | Pholm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WAKE-2wks | 1.97 ± 0.66 | 1.34 ± 0.51 | 3.91 | 0.001 |

| WAKE-24hr | 1.48 ± 0.78 | 0.82 ± 0.69 | 4.07 | <0.001 |

| Dream | 0.96 ± 0.74 | 1.25 ± 0.80 | −1.797 | 0.372 |

| Emotion | F2,98 | p | np2 | WAKE-2wks vs. WAKE-24hr | WAKE-2wks vs. Dream | WAKE-24hr vs. Dream |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amusement | 40.058 | 0.001 | 0.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Anger | 13.52 | 0.014 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.069 |

| Shame | 4.599 | 0.019 | 0.09 | 0.022 | 0.822 | 0.028 |

| Awe | 8.15 | 0.007 | 0.14 | 0.002 | 0.919 | 0.002 |

| Contempt | 3.806 | 0.035 | 0.07 | 0.042 | 0.803 | 0.053 |

| Disgust | 2.593 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.476 | 0.476 | 0.075 |

| Embarassment | 3.706 | 0.036 | 0.07 | 0.024 | 0.262 | 0.234 |

| Gratefulness | 29.23 | 0.004 | 0.37 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Guilt | 3.687 | 0.047 | 0.06 | 0.271 | 0.303 | 0.038 |

| Hatred | 6.33 | 0.065 | 0.06 | 0.316 | 0.345 | 0.059 |

| Hopefulness | 10.32 | 0.003 | 0.17 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.021 |

| Inspiredness | 15.42 | 0.002 | 0.24 | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Interest | 18.92 | 0.002 | 0.27 | 0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Joy | 12.48 | 0.007 | 0.2 | 0.098 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Love | 15.5 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.096 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pride | 19.62 | 0.004 | 0.29 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 |

| Sadness | 5.791 | 0.007 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.928 | 0.11 |

| Fear | 9.43 | 0.003 | 0.16 | 0.003 | 0.371 | <0.001 |

| Serenity | 17.36 | 0.004 | 0.26 | 0.316 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Stress | 8.06 | 0.005 | 0.141 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.862 |

| Sensuality | 19.6 | 0.005 | 0.29 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Solidarity | 14.92 | 0.009 | 0.233 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.327 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conte, F.; Cellini, N.; De Rosa, O.; Caputo, A.; Malloggi, S.; Coppola, A.; Albinni, B.; Cerasuolo, M.; Giganti, F.; Marcone, R.; et al. Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100690

Conte F, Cellini N, De Rosa O, Caputo A, Malloggi S, Coppola A, Albinni B, Cerasuolo M, Giganti F, Marcone R, et al. Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(10):690. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100690

Chicago/Turabian StyleConte, Francesca, Nicola Cellini, Oreste De Rosa, Antonietta Caputo, Serena Malloggi, Alessia Coppola, Benedetta Albinni, Mariangela Cerasuolo, Fiorenza Giganti, Roberto Marcone, and et al. 2020. "Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale" Brain Sciences 10, no. 10: 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100690

APA StyleConte, F., Cellini, N., De Rosa, O., Caputo, A., Malloggi, S., Coppola, A., Albinni, B., Cerasuolo, M., Giganti, F., Marcone, R., & Ficca, G. (2020). Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100690