Key Roles of Plasmonics in Wireless THz Nanocommunications—A Survey

Abstract

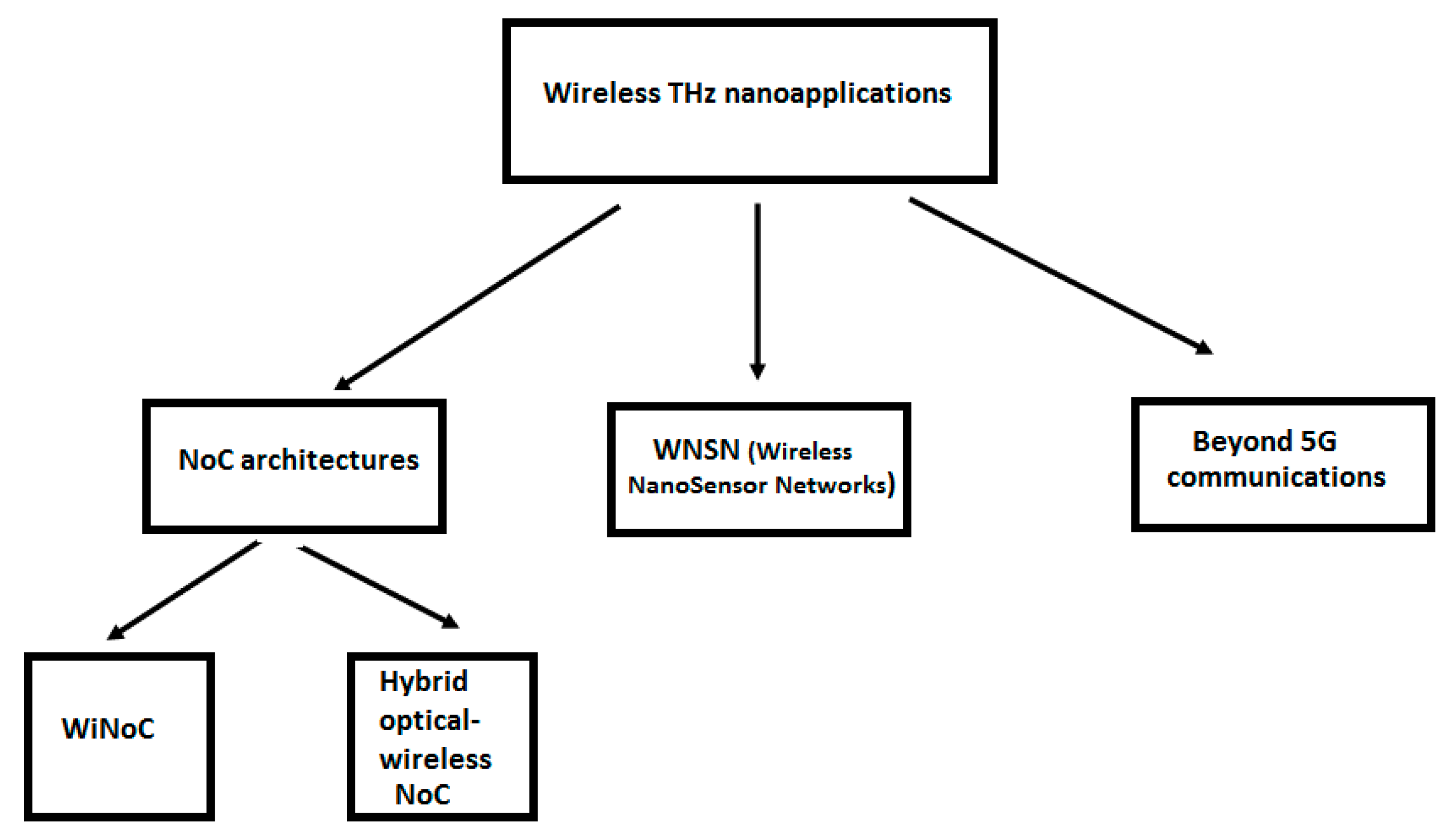

1. Introduction

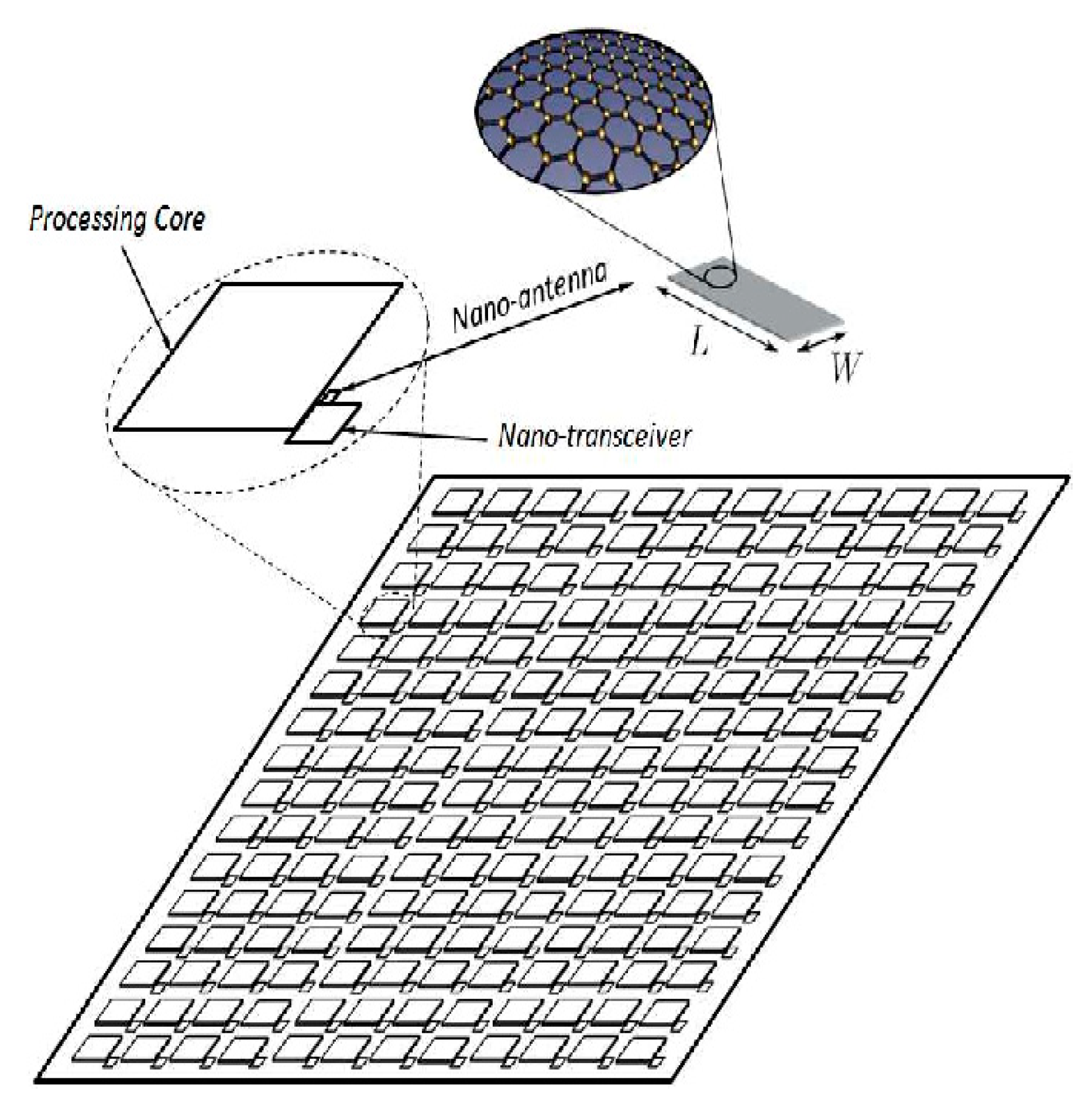

2. WiNoCs

2.1. WiNoC Architectures Potential

2.2. GWiNoCs

2.3. Hybrid Optical Wireless NoCs

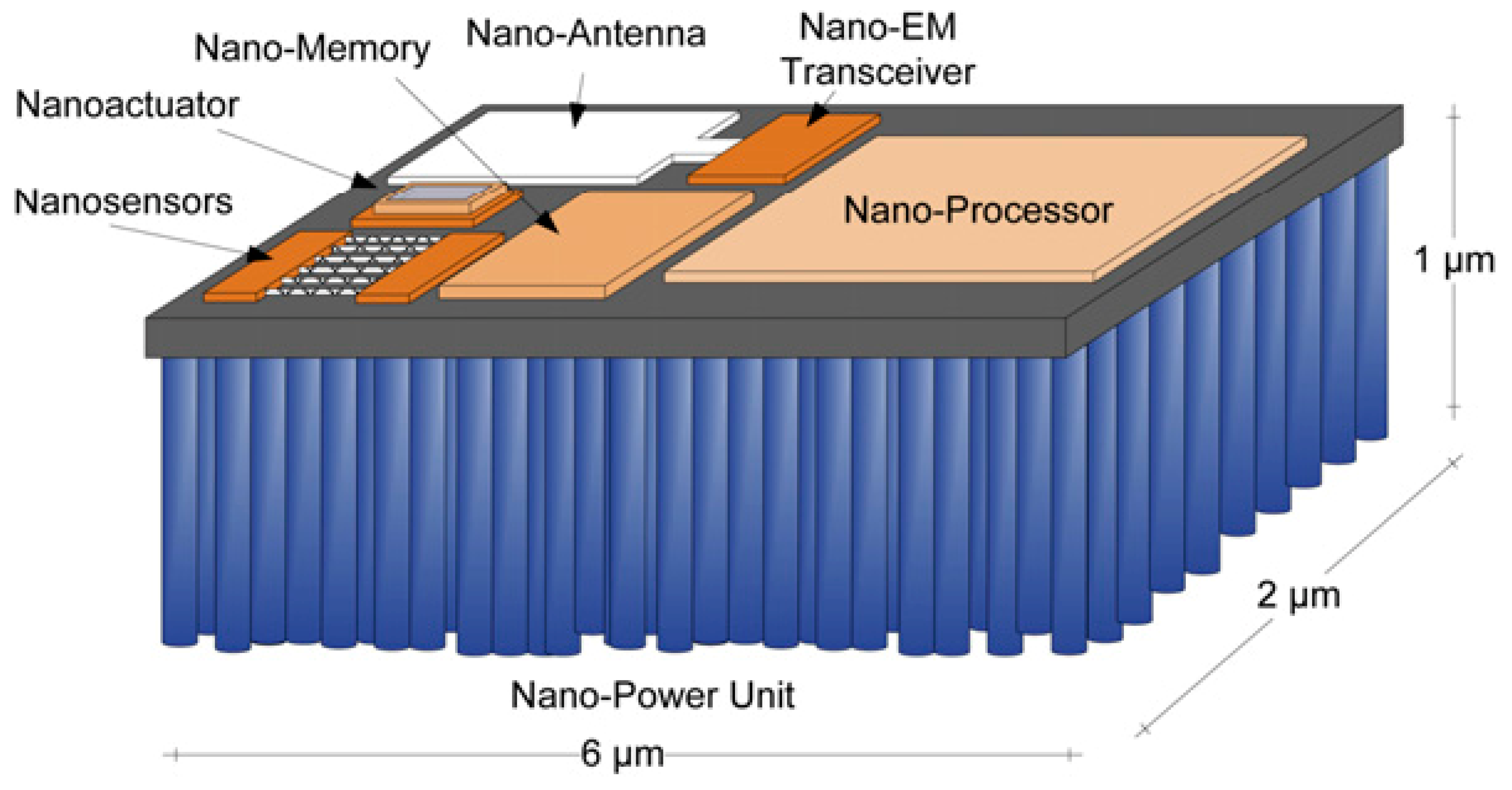

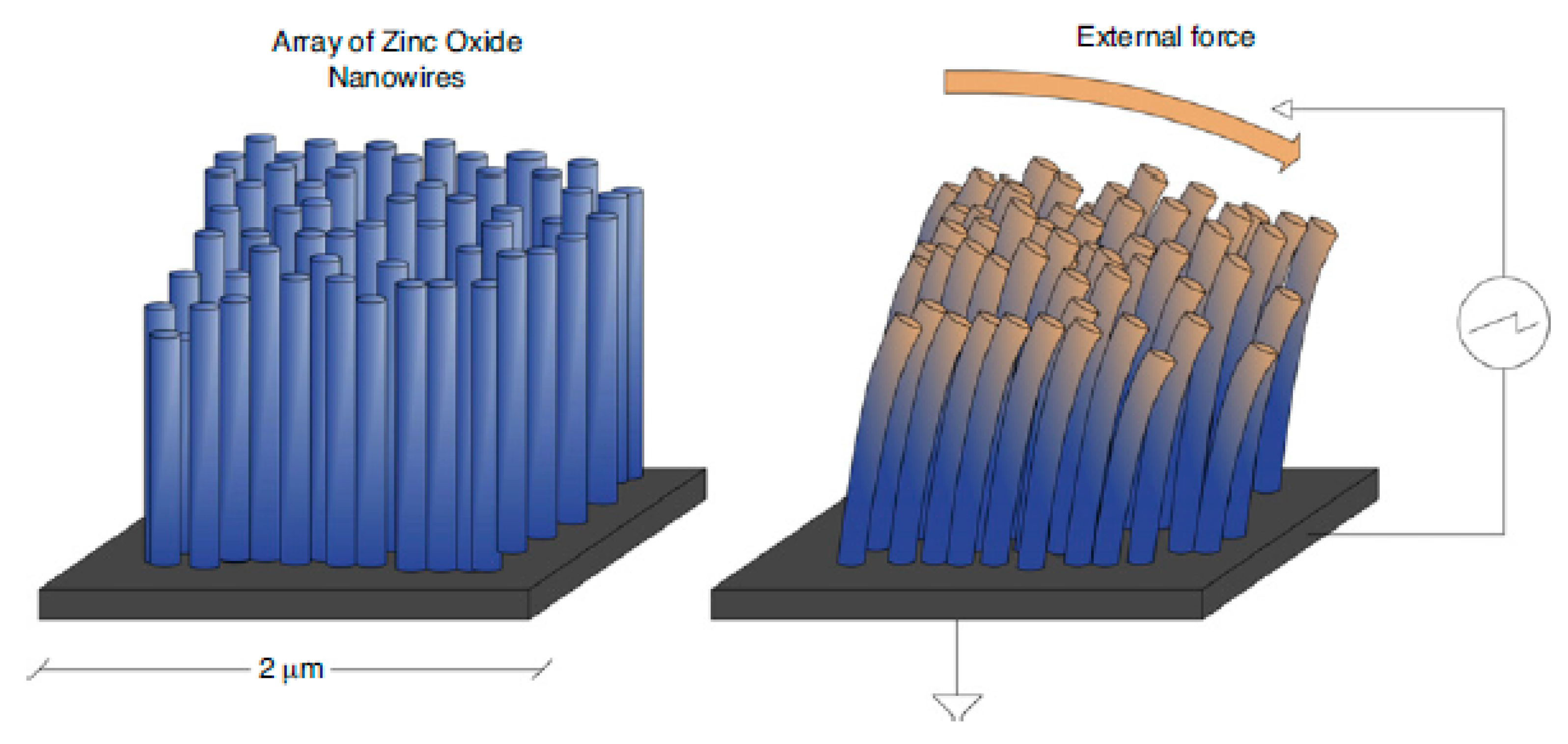

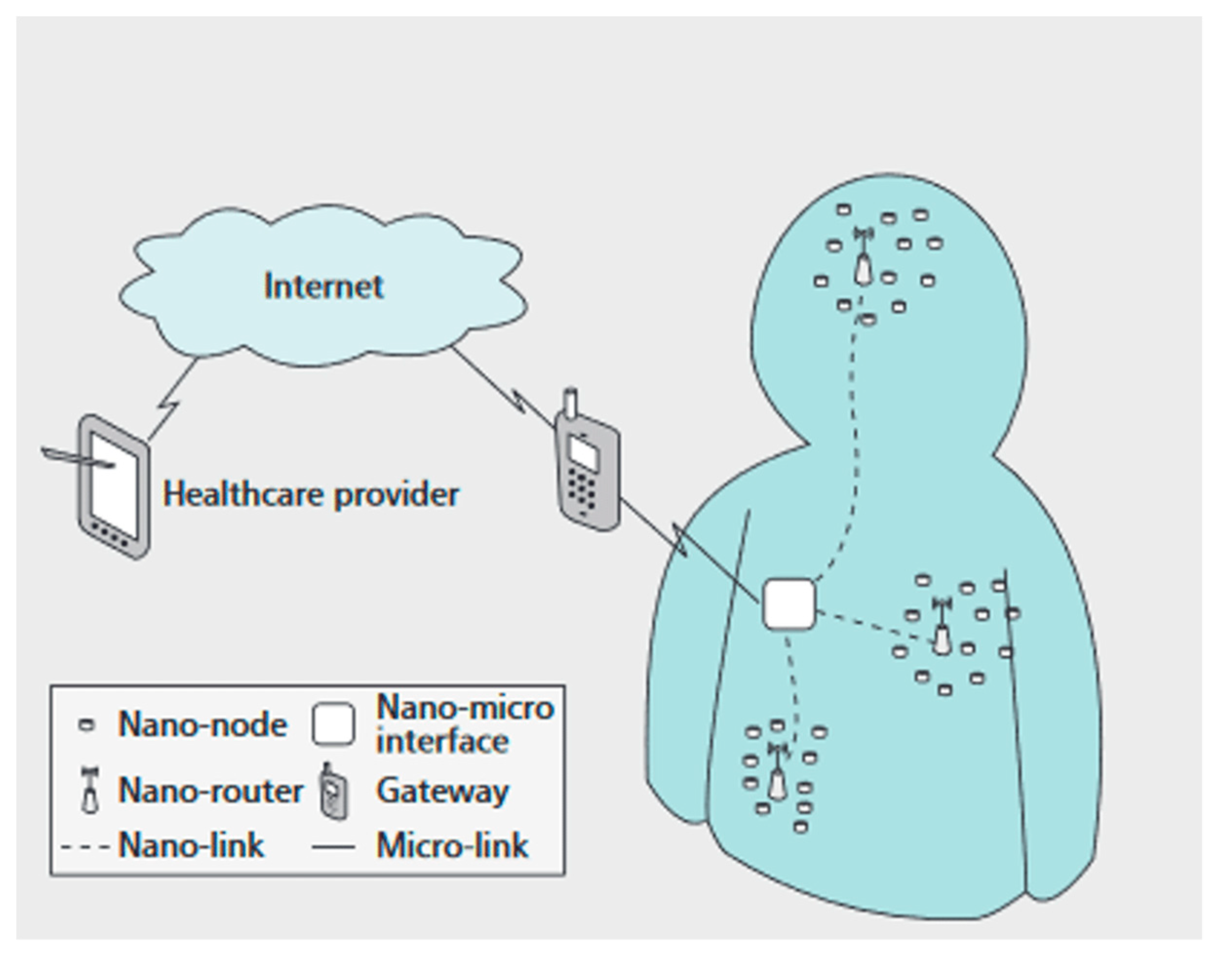

3. Wireless Nano Sensor Networks

4. Beyond 5G Networks: Towards to THz Band Communications

5. Plasmonic THz Wireless Nanoscale Link Components

5.1. Plasmonic THz Antennas

5.1.1. Design Issues

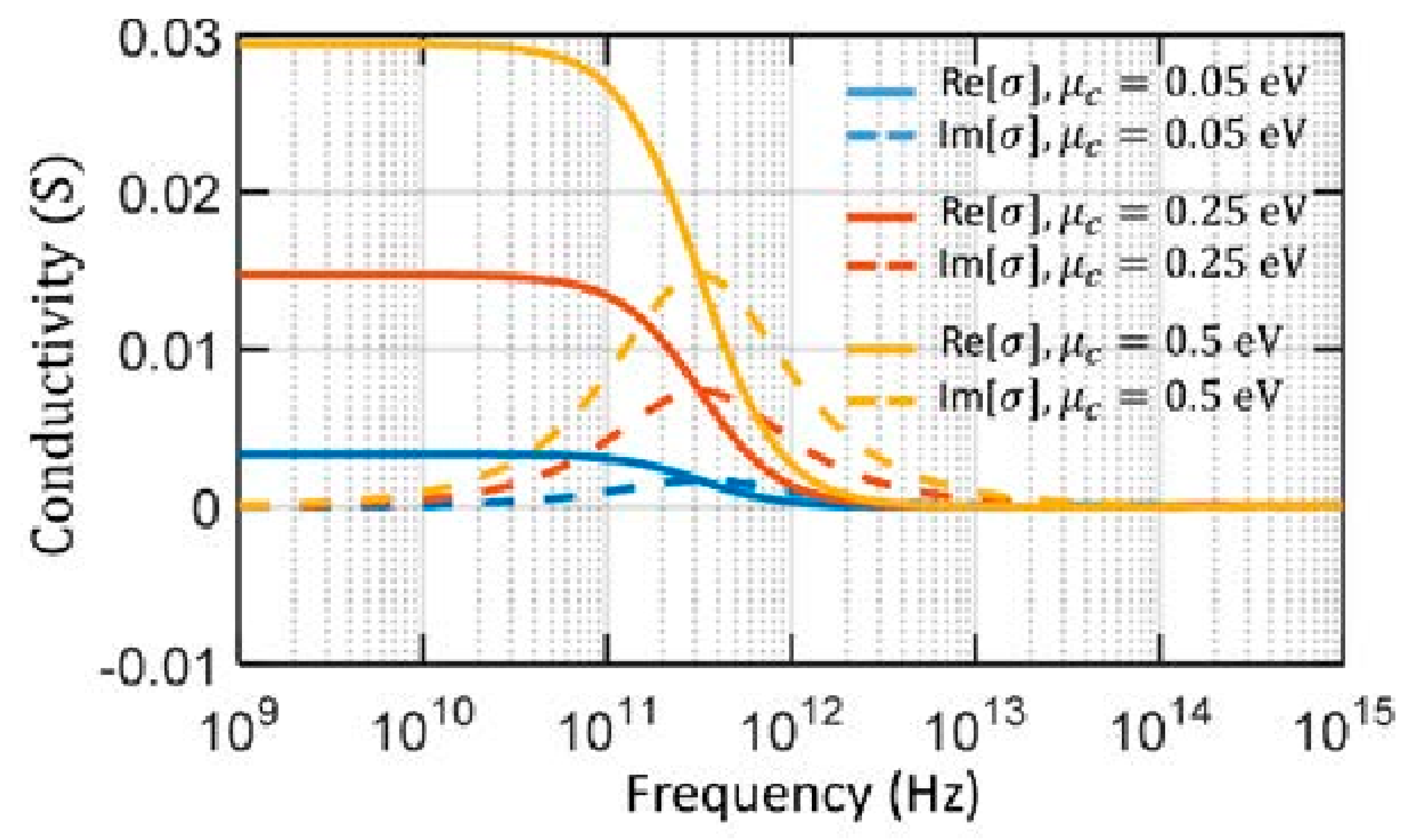

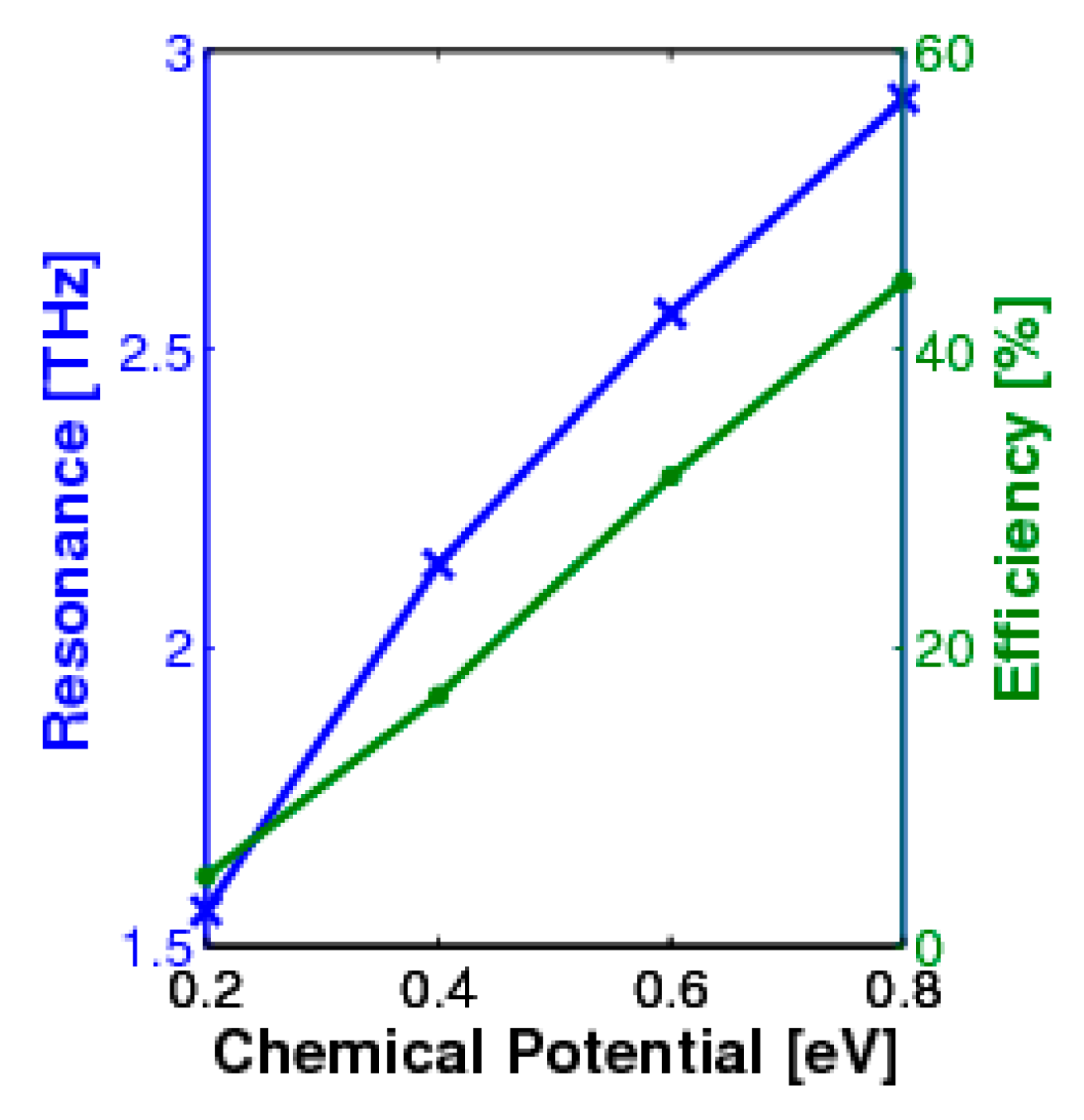

5.1.2. Graphennas

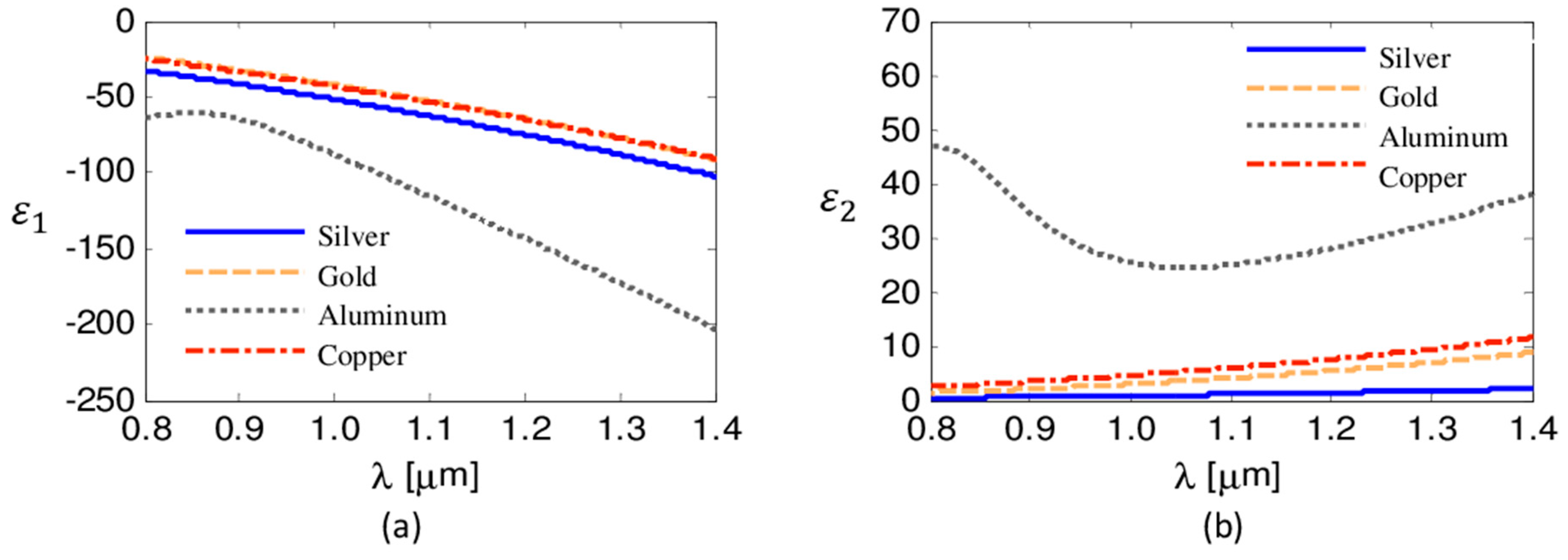

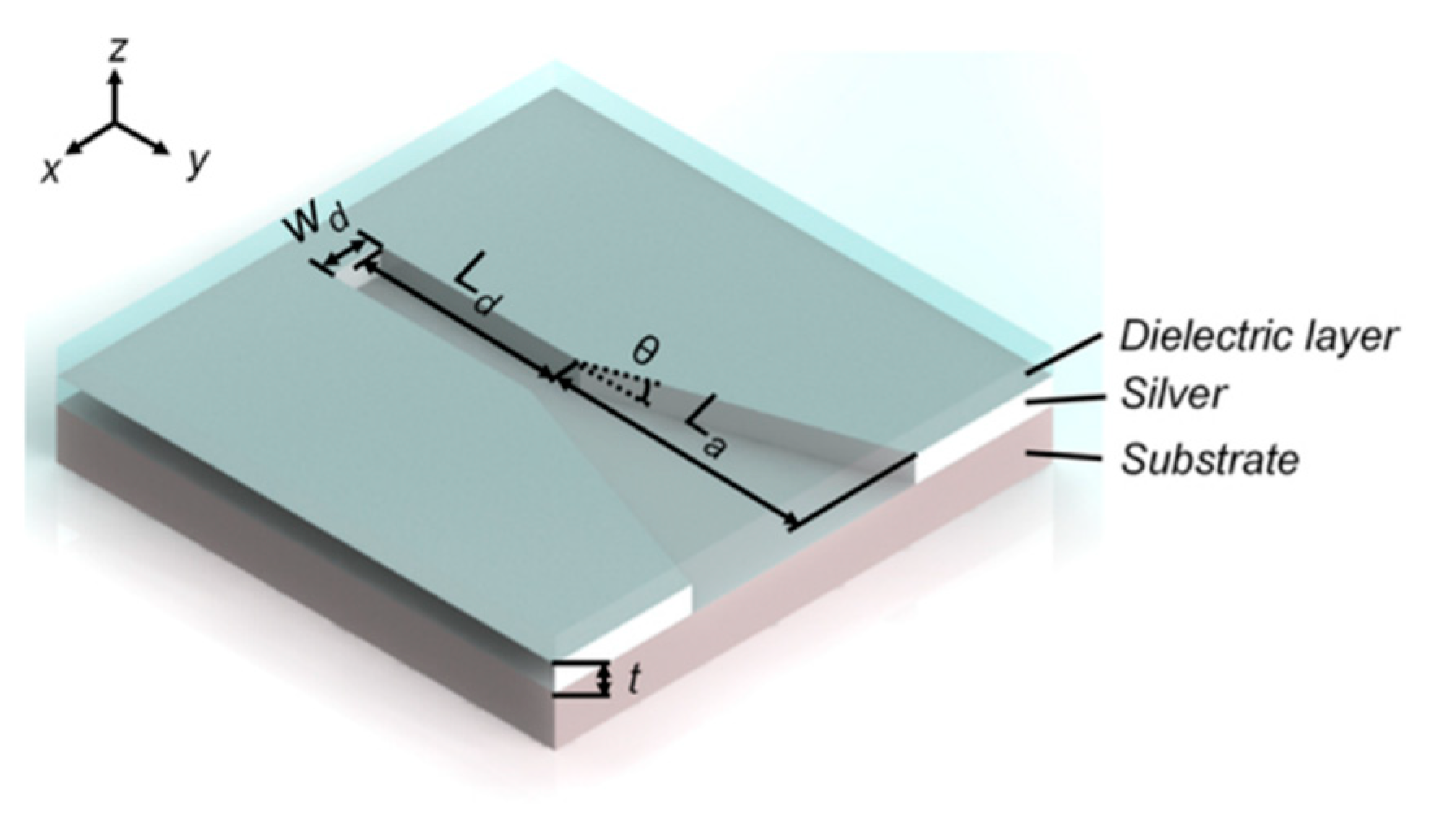

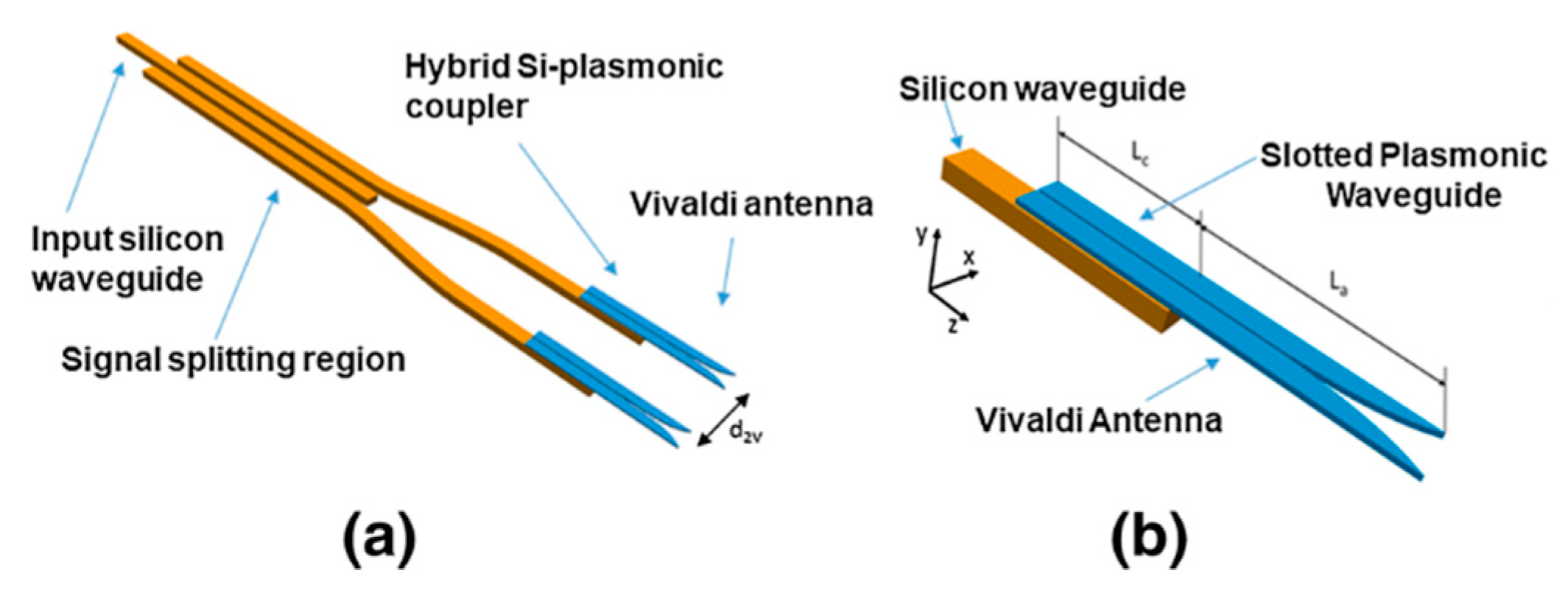

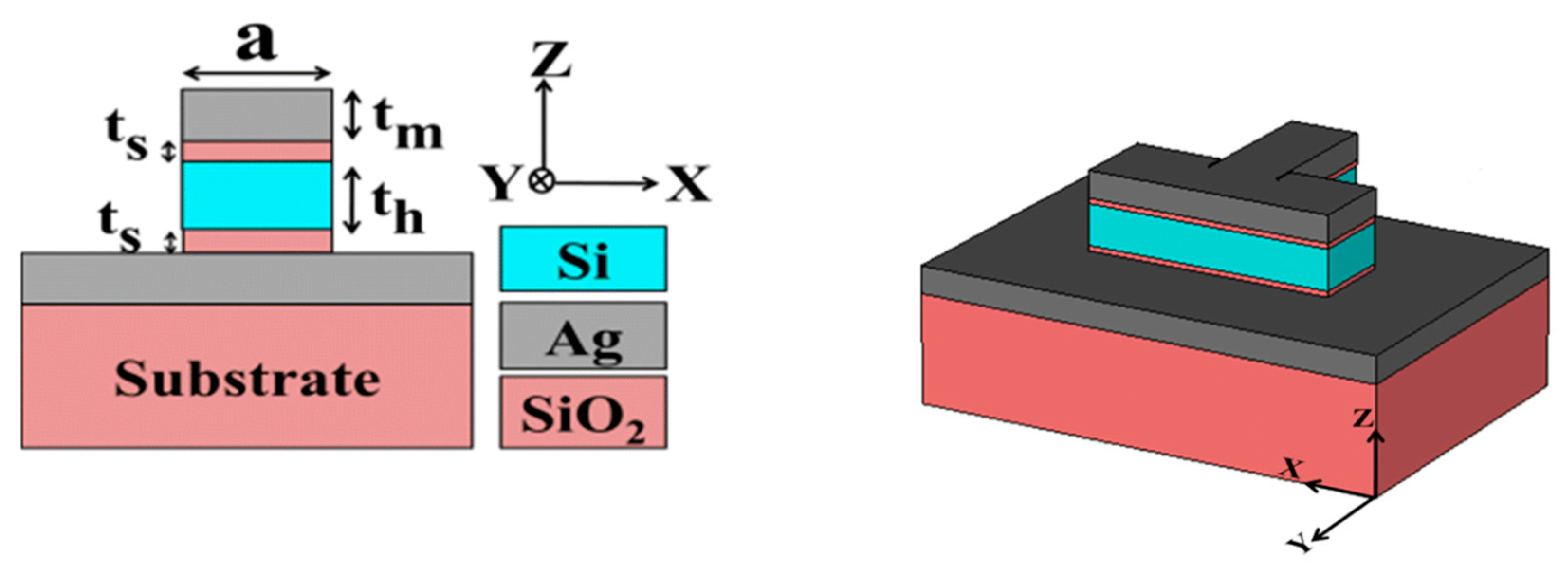

5.1.3. Other Plasmonic Nanoantennas

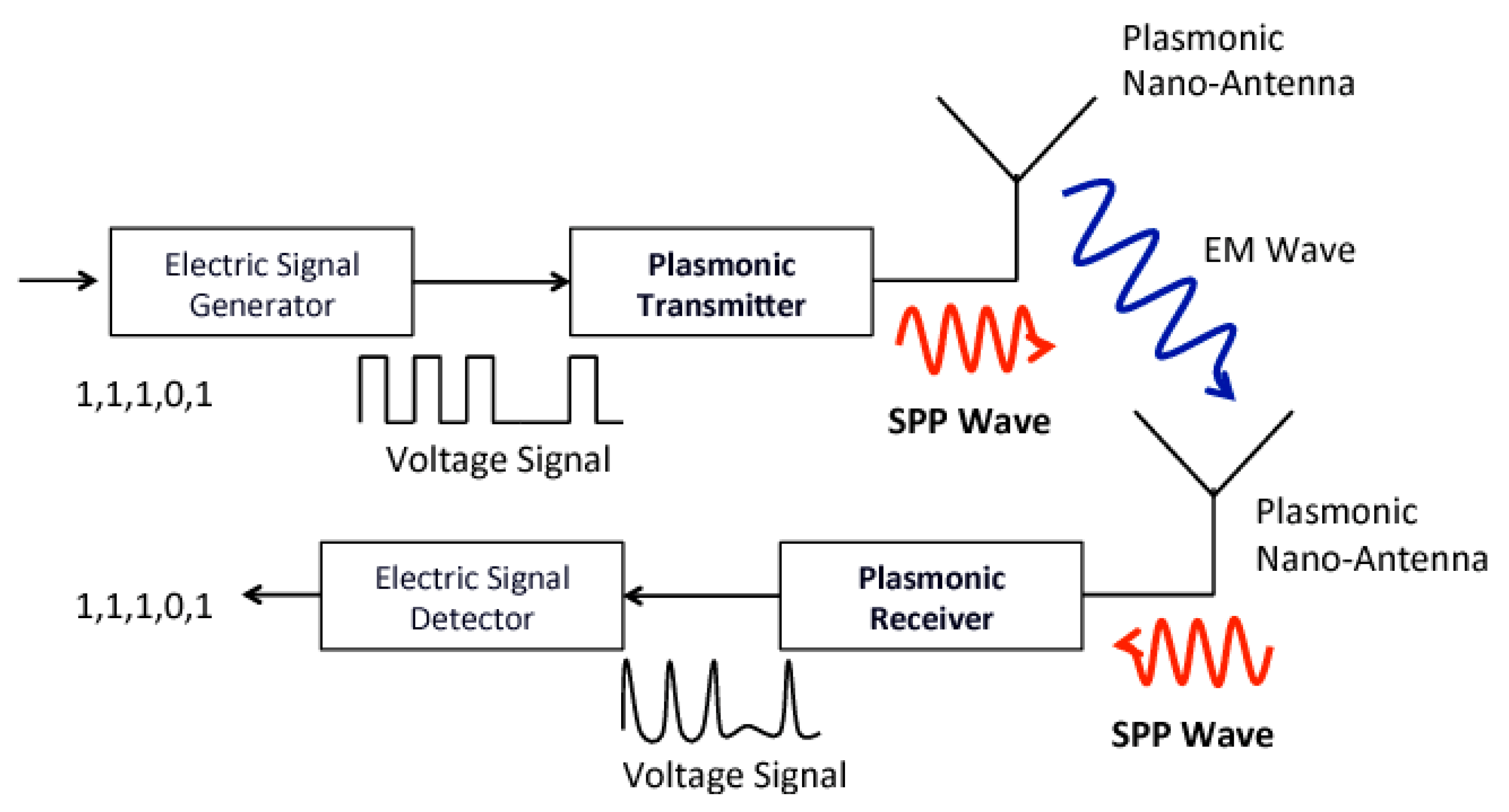

5.2. THz Band Nanotransceivers

5.2.1. THz Band Transmitters

5.2.2. THz Band Receivers

5.2.3. Graphene Based THz Transceiver Components

6. Summary and Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Index, C.V.N. Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology 2015–2020; White Paper; CISCO: San Jose, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Index, C.V.N. Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology 2016–2021; White Paper; CISCO: San Jose, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kürner, T.; Priebe, S. Towards THz communications—Status in research, standardization and regulation. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2014, 35, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.R. Towards a new internet for the year 2030 and beyond. In The 3rd ITU IMT-2020/5G Workshop; International Telecommunication Union (ITU): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abadal, S.; Alarcon, E.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Lemme, M.C.; Nemirovsky, M. Graphene-Enabled Wireless Communication for Massive Multicore Architectures. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fortuno, F.J.; Espinosa-Soria, A.; Martinez, A. Exploiting metamaterials, plasmonics and nanoantennas concepts in silicon photonics. J. Opt. 2016, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Shubair, R.M. Nanoscale Communication: State-of-Art and Recent Advances. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.07722. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, V.; Moltchanov, D.; Komar, M.; Antonov, A.; Kustarev, P.; Rakheja, S.; Koucheryavy, Y. Terahertz Band Intra-Chip Communications: Can Wireless Links Scale Modern x86 CPUs? IEEE Access 2017, 5, 6095–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Afshari, E. Filling the terahertz gap with sand: High-power terahertz radiators in silicon. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Bipolar/BiCMOS Circuits and Technology Meeting-BCTM, Boston, MA, USA, 26–28 October 2015; pp. 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Seok, E.; Shim, D.; Mao, C.; Han, R.; Sankaran, S.; Cao, C.; Knap, W.; Kenneth, K.O. Progress and challenges towards terahertz CMOS integrated circuits. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2010, 45, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. A Survey of ReRAM-Based Architectures for Processing-In-Memory and Neural Networks. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2019, 1, 75–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, P.; Li, S.; Xu, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y. PRIME: A novel processing-in-memory architecture for neural network computation in ReRAM-based main memory. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM/IEEE 43rd Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), Seoul, Korea, 18–22 June 2016; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Paper on AI Chip Technologies; Beijing Innovation Center for Future Chips (ICFC): Beijing, China, 2018.

- Choi, W.; Duraisamy, K.; Kim, R.G.; Doppa, J.R.; Pande, P.P.; Marculescu, D.; Marculescu, R. On-Chip Communication Network for Efficient Training of Deep Convolutional Networks on Heterogeneous Manycore Systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2018, 67, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thraskias, C.A.; Lallas, E.N.; Neumann, N.; Schares, L.; Offrein, B.J.; Henker, R.; Plettemeier, D.; Ellinger, F.; Leuthold, J.; Tomkos, I. Survey of Photonic and Plasmonic Chip-Scale Interconnect Technologies for Intra-Datacenter and High-Performance Computing Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 2758–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, L.P.; Pande, P.; Xie, Y. Networks-on-chip in emerging interconnect paradigms: Advantages and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Networks-on-Chip, Washington, DC, USA, 10–13 May 2009; pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Zyuban, V.; Tullsen, D.M. Interconnections in Multi-core Architectures: Understanding Mechanisms, Overheads and Scaling. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA’05), Madison, WI, USA, 4–8 June 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kash, J.A.; Pepeljugoski, P.; Doany, F.E.; Schow, C.L.; Kuchta, D.M.; Schares, L.; Budd, R.; Libsch, F.; Dangel, R.; Horst, F. Communication Technologies for Exascale Systems. In Proceedings of the SPIE OPTO: Integrated Optoelectronic Devices, San Jose, CA, USA, 24 January 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, M.O.; Ahmadinia, A.; Shahrabi, A. Heterogeneous 3d network-on-chip architectures: Area and power aware design techniques. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2013, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socher, E.; Chang, M.-C.F. Can RF Help CMOS Processors? IEEE Commun. Mag. 2007, 45, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalighi, M.A.; Uysal, M. Survey on free space optical communication: A communication theory perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2014, 16, 2231–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, A.; Bergman, K.; Carloni, L.P. Photonic networks-on-chip for future generations of chip multiprocessors. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2008, 57, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Pasricha, S. Silicon nanophotonics for future multicore architectures: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Des. Test 2014, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Ganguly, A.; Pande, P.P.; Belzer, B.; Heo, D. Wireless NoC as interconnection backbone for multicore chips: Promises and challenges. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2012, 2, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matolak, D.W.; Kodi, A.; Kaya, S.; Ditomaso, D.; Laha, S.; Rayess, W. Wireless networks-on-chips: Architecture, wireless channel, and devices. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2012, 19, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Chang, K.; Deb, S.; Pande, P.P.; Belzer, B.; Teuscher, C. Scalable hybrid wireless network-on-chip architectures for multicore systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2011, 60, 1485–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, M.O.; Vien, Q.T.; Ahmadinia, A.; Yakovlev, A.; Tong, K.F.; Mak, T.S. A resilient 2-D waveguide communication fabric for hybrid wired-wireless NoC design. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2017, 28, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Jornet, J.M.; Han, C. TeraNets: Ultra-broadband communication networks in the terahertz band. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2014, 21, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correas-Serrano, D.; Gomez-Diaz, J.S. Graphene-based Antennas for Terahertz Systems: A Review. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.00371. [Google Scholar]

- Samaiyar, A.; Ram, S.S.; Deb, S. Millimeter-Wave Planar Log Periodic Antenna for On-Chip Wireless Interconnects. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP 2014), The Hague, The Netherlands, 6–11 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llatser, I.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Alarcón, E.; Jornet, J.M.; Mestres, A.; Lee, H.; Pareta, J.S. Scalability of the Channel Capacity in Graphene-enabled Wireless Communications to the Nanoscale. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2015, 63, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafari, M.; Feng, L.; Jornet, J.M. On-chip Wireless Optical Channel Modeling for Massive Multi-Core Computing Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), SanFransisco, CA, USA, 19–22 March 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llatser, I.; Kremers, C.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Jornet, J.M.; Alarcón, E.; Chigrin, D.N. Graphene-based Nano-Patch Antenna for Terahertz Radiation. Photonics Nanostruct.-Fundam. Appl. 2012, 10, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornet, J.M.; Akyildiz, I.F. Graphene-Based Nano-Antennas for Electromagnetic Nanocommunications in the Terahertz Band. In Proceedings of the Fourth European Conference on Antennas and Propagation, Barcelona, Spain, 12–16 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Jornet, J.M. Electromagnetic wireless nanosensor networks. Nano Commun. Netw. 2010, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Qiu, T.; Lu, W.; Ni, Z. Plasmons in graphene: Recent progress and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2013, 74, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakheja, S.; Sengupta, P. Gate-voltage tunability of plasmons in single and multi-layer graphene structures: Analytical description and concepts for terahertz devices. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.00658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jenkins, K.A.; Valdes-Garcia, A.; Farmer, D.B.; Zhu, Y.; Bol, A.A.; Dimitrakopoulos, C.; Zhu, W.; Xia, F.; Avouris, P.; et al. State-of-the-art graphene high-frequency electronics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3062–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Alu, A. All-graphene terahertz analog nanodevices and nanocircuits. In Proceedings of the 2013 7th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Gothenburg, Sweden, 8–12 April 2013; pp. 697–698. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, L.; Foster, A.C. Waveguide-fed optical hybrid plasmonic patch nano-antenna. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 18326–18335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Gong, H.; Li, Q.; Qiu, M. Plasmonic sectoral horn nanoantennas. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 3204–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Qiu, M. Broadband nanophotonic wireless links and networks using on-chip integrated plasmonic antennas. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanca, G.; Calo, G.; Kaplan, A.E.; Bassi, P.; Petruzzelli, V. Integrated Vivaldi plasmonic antenna for wireless on-chip optical communications. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 16214–16227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, A.; Kocabas, S.E. Beam steering and impedance matching of plasmonic horn nanoantennas. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 25647–25652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango, F.B.; Kwadrin, A.; Koenderink, A.F. Plasmonic Antennas Hybridized with Dielectric Waveguides. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 10156–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRose, C.T.; Kekatpure, R.D.; Trotter, D.C.; Starbuck, A.; Wendt, J.R.; Yaacobi, A.; Watts, M.R.; Chettiar, U.; Engheta, N.; Davids, P.S. Electronically controlled optical beam-steering by an active phased array of metallic nanoantennas. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 5198–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calo, G.; Bellanca, G.; Kaplan, A.E.; Bassi, P.; Petruzzelli, V. Double Vivaldi antenna for wireless optical networks on chip. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2018, 50, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, G.; Bellanca, G.; Kaplan, A.E.; Kaplan, A.E.; Bassi, P.; Petruzzelli, V. Array of plasmonic Vivaldi antennas coupled to silicon waveguides for wireless networks through on-chip optical technology–WiNOT. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 30267–30277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayyar, A.; Puri, V.; Le, D.N. Internet of Nano Things (IoNT): Next Evolutionary Step in Nanotechnology. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 7, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Jornet, J.M. The Internet of Nano-Things. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Mag. 2010, 17, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupani, V.; Kargathara, S.; Sureja, J. A Review on Wireless Nanosensor Networks Based on Electromagnetic Communication. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2015, 6, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer, C.; Helbling, T.; Obergfell, D.; Schöberle, B.; Tripp, M.K.; Jungen, A.; Roth, S.; Bright, V.M.; Hierold, C. Fabrication of single walled carbon nanotube based pressure sensors. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfer, C.; Jungen, A.; Hierold, C. Fabrication of discrete nanoscaled force sensors based on single-walled carbon nanotubes. IEEE Sens. J. 2006, 6, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfer, C.; Linderman, R.; Obergfell, D.; Jungen, A.; Roth, S.; Hierold, C. Nano electromechanical displacement sensing based on single walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2006, 7, 1449–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo-Dinh, T.; Cullum, B.M.; Stokes, D.L. Nanosensors and biochips: Frontiers in biomolecular diagnostics. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 74, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouris, P. Carbon nanotube electronics and photonics. Phys. Today 2009, 62, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonzon, C.R.; Stuart, D.A.; Zhang, X.; McFarland, A.; Haynes, C.L.; Van Duyne, R.P. Towards advanced chemical and biological nanosensors an overview. Talanta 2005, 67, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Thostenson, E.T.; Chou, T.-W. Sensors and actuators based on carbon nanotubes and their composites: A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Kim, N.H.; Kuila, T.; Lau, K.-T.; Lee, J.H. Electrochemical performance of a graphene-polypyrrole nanocomposite as a supercapacitor electrode. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 295202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.; King, B.; Burkhead, T.; Xu, P.; Bessler, N.; Terentjev, E.; Panchapakesan, B. Graphene-nanoplatelet-based photomechanical actuators. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 045501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Tan, Z.; Kuykendall, T.; An, E.J.; Fu, Y.; Battaglia, V.; Zhang, Y. Multilayer nanoassembly of sn-nanopillar arrays sandwiched between graphene layers for high-capacity lithium storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Towards self-powered nanosystems: From nanogenerators to nanopiezotronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 3553–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Song, J. Piezoelectric nanogenerators based on zinc oxide nanowire arrays. Science 2006, 312, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.W. Dyadic green’s functions and guided surface waves for a surface conductivity model of graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 064302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.-M.; Bol, A.A.; Jenkins, K.A.; Xia, F.; Farmer, D.B.; Zhu, Y.; Avouris, P. High-frequency, scaled graphene transistors on diamond-like carbon. Nature 2011, 472, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Wei, H.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H. Recent advances in plasmonic sensors. Sensors 2014, 14, 7959–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Drakeley, S.; Millyard, M.J.; Murphy, A.; White, R.; Spigone, E.; Kivioja, J.; Baumberg, J.J. Zero-Reflectance Metafilms for Optimal Plasmonic Sensing. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, A.; Aid, S.R.; Xie, F. Infra-Red Plasmonic Sensors. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanovic-Miklicanin, E.; Maksimovic, M. Nanosensors applications in agriculture and food industry, Technical paper. Bull. Chem. Technol. Bosnia Herzeg. 2016, 47, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Vj, L. Nanoscale Materials and Devices for Future Communication Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, J.F.; Schulkin, B.; Huang, F.; Gary, D.; Barat, R.; Oliveira, F.; Zimdars, D. THz imaging and sensing for security applications explosives, weapons and drugs. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2005, 20, S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hao, Y.; Alomainy, A.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Qaraqe, K. Channel modelling of human tissues at terahertz band. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference Workshops (WCNCW), Doha, Qatar, 3–6 April 2016; pp. 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafari, M.; Jornet, J.M. Metallic plasmonic nano-antenna for wireless optical communication in intra-body nanonetworks. In Proceedings of the 10th EAI International Conference on Body Area Networks, Sydney, Australia, 28–30 September 2015; pp. 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, B.S.; Gelev, V.; Bishop, A.R.; Usheva, A.; Rasmussen, K. DNA breathing dynamics in the presence of a terahertz field. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 374, 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, D.; Limaj, O.; Janner, D.; Etezadi, D.; García de Abajo, F.J.; Pruneri, V.; Altug, H. Mid-infrared plasmonic biosensing with graphene. Science 2015, 349, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plusquellic, D.F.; Heilweil, E.J. Terahertz spectroscopy of biomolecules. In Terahertz Spectroscopy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Huang, H.; Akinwande, D.; Alu, A. Graphene-Based Plasmonic Platform for Reconfigurable Terahertz Nanodevices. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Sakhdari, M.; Hajizadegan, M.; Shahini, A.; Akinwande, D.; Chen, P.Y. Toward transparent and self-activated graphene harmonic transponder sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 173503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Pyattaev, A.; Moltchanov, D.; Koucheryavy, Y. Terahertz band communications: Applications, research challenges, and standardization activities. In Proceedings of the 2016 8th International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems and Workshops (ICUMT), Lisbon, Portugal, 18–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, J.; Moeller, L. Review of terahertz and subterahertz wireless communications. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, A.; Ruder, M.A.; Akyildiz, I.F.; Gerstacker, W.H. Los and nlos channel modeling for terahertz wireless communication with scattered rays. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Austin, TX, USA, 8–12 December 2014; pp. 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, S.; Lopez-Diaz, D.; Antes, J.; Boes, F.; Henneberger, R.; Leuther, A.; Tessmann, A.; Schmogrow, R.; Hillerkuss, D.; Palmer, R.; et al. Wireless sub-THz communication system with high data rate. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, H.; Shao, T.; Fice, M.J.; Anandarajah, P.M.; Renaud, C.C.; Van Dijk, F.; Barry, L.P.; Seeds, A.J. 100 Gb/s Multicarrier THz Wireless Transmission System with High Frequency Stability Based on A Gain-Switched Laser Comb Source. IEEE Photonics J. 2015, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Caballero, A.; Dogadaev, A.; Arlunno, V.; Borkowski, R.; Pedersen, J.S.; Deng, L.; Karinou, F.; Roubeau, F.; Zibar, D.; et al. 100 Gbit/s hybrid optical fiber-wireless link in the W-band (75–110 GHz). Opt. Express 2011, 19, 24944–24949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsuma, T.; Ducournau, G.; Renaud, C.C. Advances in terahertz communications accelerated by photonics. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayan, H.; Amin, O.; Shubair, R.M.; Alouini, M.S. Terahertz communication: The opportunities of wireless technology beyond 5G. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Communication Technologies and Networking, Marrakech, Morocco, 2–4 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, M.; Bonjour, R.; Salamin, Y.; Abrecht, F.C.; Haffner, C.; Heni, W.; Hoessbacher, C.; Baeuerle, B.; Josten, A.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; et al. Plasmonic Modulators for Microwave Photonics Applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 Asia Communications and Photonics Conference (ACP), Guangzhou, China, 10–13 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, R.; Novak, D. Realizing 5G: Microwave Photonics for 5G Mobile Wireless Systems. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2015, 16, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Marpaung, D.; Choudhary, A.; Eggleton, B.J. Highly selective and reconfigurable Si3N4 RF photonic notch filter with negligible RF losses. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), San Jose, CA, USA, 14–19 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, I.F.; Rodriguez, S.; Puerta, R.; Vegas Olmos, J.J.; Cerqueira, J.A.; Da Silva, L.G.; Spadoti, D.; Monroy, I.T. Photonic Downconversion and Optically Controlled Reconfigurable Antennas in mm-waves Wireless Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), Ananheim, CA, USA, 20–24 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marpaung, D.; Roeloffzen, C.; Heideman, R.; Leinse, A.; Sales, S.; Capmany, J. Integrated microwave photonics. Laser Photonics Rev. 2013, 7, 506–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, R.; Singleton, M.; Gebrewold, S.A.; Salamin, Y.; Abrecht, F.C.; Baeuerle, B.; Josten, A.; Leuchtmann, P.; Hafner, C.; Leuthold, J. Ultra-Fast Millimeter Wave Beam Steering. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2016, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayan, H.; Amin, O.; Shihada, B.; Shubair, R.M.; Alouini, M.S. Terahertz Band: The Last Piece of RF Spectrum Puzzle for Communication Systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.05043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Pang, X.; Ozolins, O.; Yu, X.; Hu, H.; Yu, J.; Guan, P.; Da Ros, F.; Popov, S.; Jacobsen, G.; et al. 0.4 THz photonic-wireless link with 106 Gb/s single channel bitrate. IEEE J. Lightwave Technol. 2018, 36, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, C.; Chelladurai, D.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Josten, A.; Baeuerle, B.; Heni, W.; Watanabe, T.; Cui, T.; Cheng, B.; Saha, S.; et al. Low-loss plasmon-assisted electro-optic modulator. Nature 2018, 556, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeuerle, B.; Heni, W.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Josten, A.; Haffner, C.; Watanabe, T.; Elder, D.L.; Dalton, L.R.; Leuthold, J. Plasmonic-organic hybrid modulators for optical interconnects beyond 100G/λ. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), San Jose, CA, USA, 13–18 May 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoessbacher, C.; Josten, A.; Baeuerle, B.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Hettrich, H.; Salamin, Y.; Heni, W.; Haffner, C.; Kaiser, C.; Schmid, R.; et al. Plasmonic modulator with >170 GHz bandwidth demonstrated at 100 GBd NRZ. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummethala, S.; Harter, T.; Köhnle, K.; Muehlbrandt, S.; Kutuvantavida, Y.; Kemal, J.N.; Schaefer, J.; Massler, H.; Tessmann, A.; Garlapati, S.K.; et al. Terahertz-to-optical conversion using a plasmonic modulator. In Proceedings of the CLEO-Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, OSA Technical Digest (Optical Society of America, 2018), paper STu3D.4, San Jose, CA, USA, 13–18 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burla, M.; Hoessbacher, C.; Heni, W.; Haffner, C.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Werner, W.; Watanabe, T.; Massler, H.; Elder, D.L.; Dalton, L.R.; et al. 500 GHz plasmonic Mach-Zehnder modulator enabling sub-THz microwave photonics. APL Photonics 2019, 4, 056106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummethala, S.; Harter, T.; Koehnle, K.; Li, Z.; Muehlbrandt, S.; Kutuvantavida, Y.; Kemal, J.; Schaefer, J.; Tessmann, A.; Kumar Garlapati, S.; et al. THz-to-Optical Conversion in Wireless Communications Using an Ultra-Broadband Plasmonic Modulator. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Arezoomandan, S.; Condori, H.; Sensale-Rodriguez, B. Graphene terahertz devices for communications applications. Nano Comm. Netw. 2016, 10, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornet, J.M.; Akyildiz, I.F. Graphene-based plasmonic nanotransceiver for terahertz band communication. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP 2014), Hague, The Netherlands, 6–11 April 2014; pp. 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elayan, H.; Shubair, R.M.; Kiourti, A. On Graphene-based THz Plasmonic Nano-Antennas. In Proceedings of the 16th Mediterranean Microwave Symposium (MMS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–16 November 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

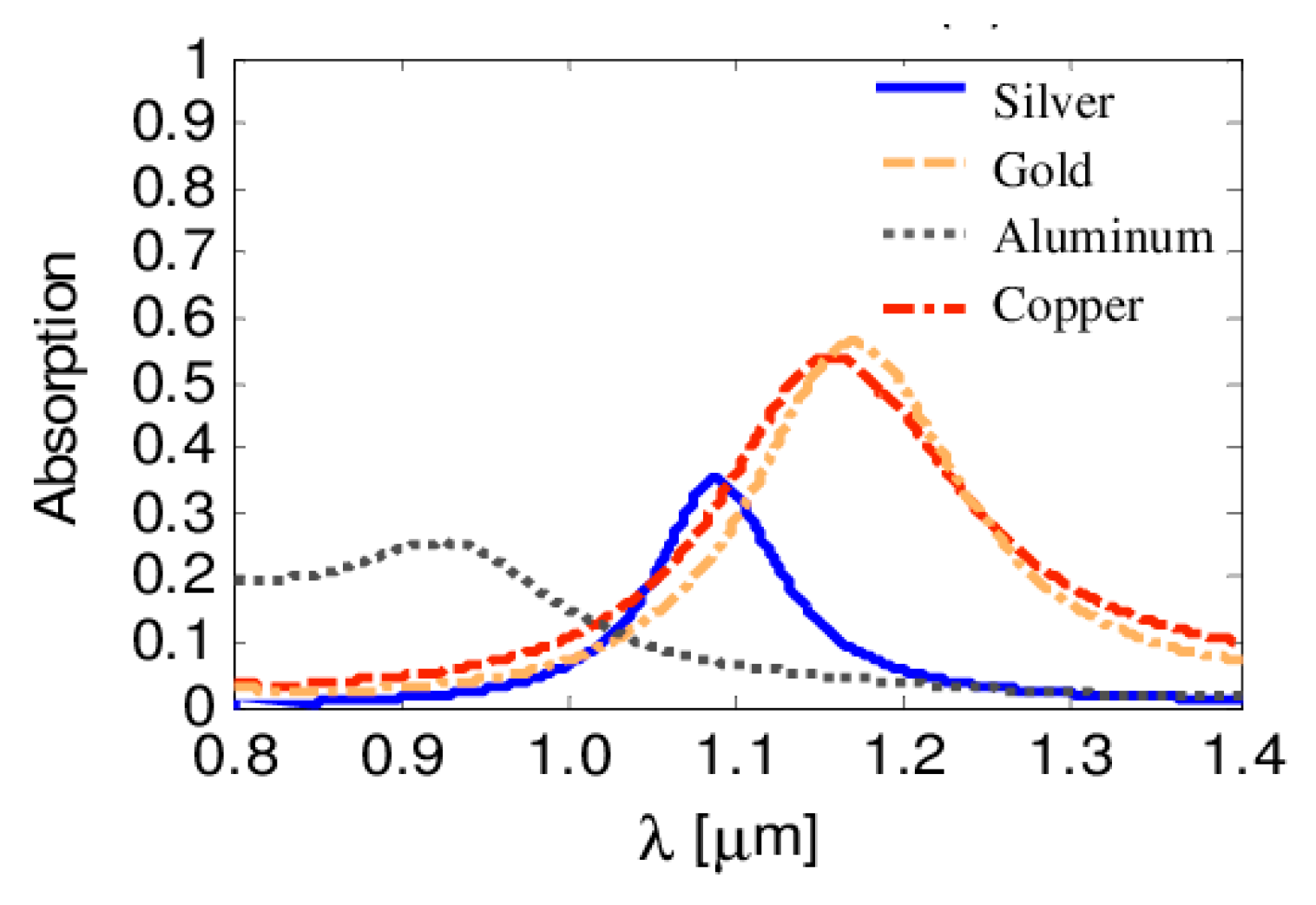

- Mohammadi, A.; Sandoghdar, V.; Agio, M. Gold, copper, silver and aluminum nanoantennas to enhance spontaneous emission. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2009, 6, 2024–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadal, S.; Hosseininejad, S.E.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Alarcón, E. Graphene-based Terahertz Antennas for Area-Constrained Applications. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Barcelona, Spain, 5–7 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahab, M.A.; Dawoud, S.; Zainud-Deen, H.; Malhat, H.A. Tapered Metal Nanoantenna Structures for Absorption Enhancement in GaAs Thin-Film Solar Cells. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Mech. 2018, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Llatser, I.; Kremers, C.; Chigrin, D.; Jornet, J.M.; Lemme, M.C.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Alarcón, E. Radiation Characteristics of Tunable Graphennas in the Terahertz Band. Radioeng. J. 2012, 21, 946–953. [Google Scholar]

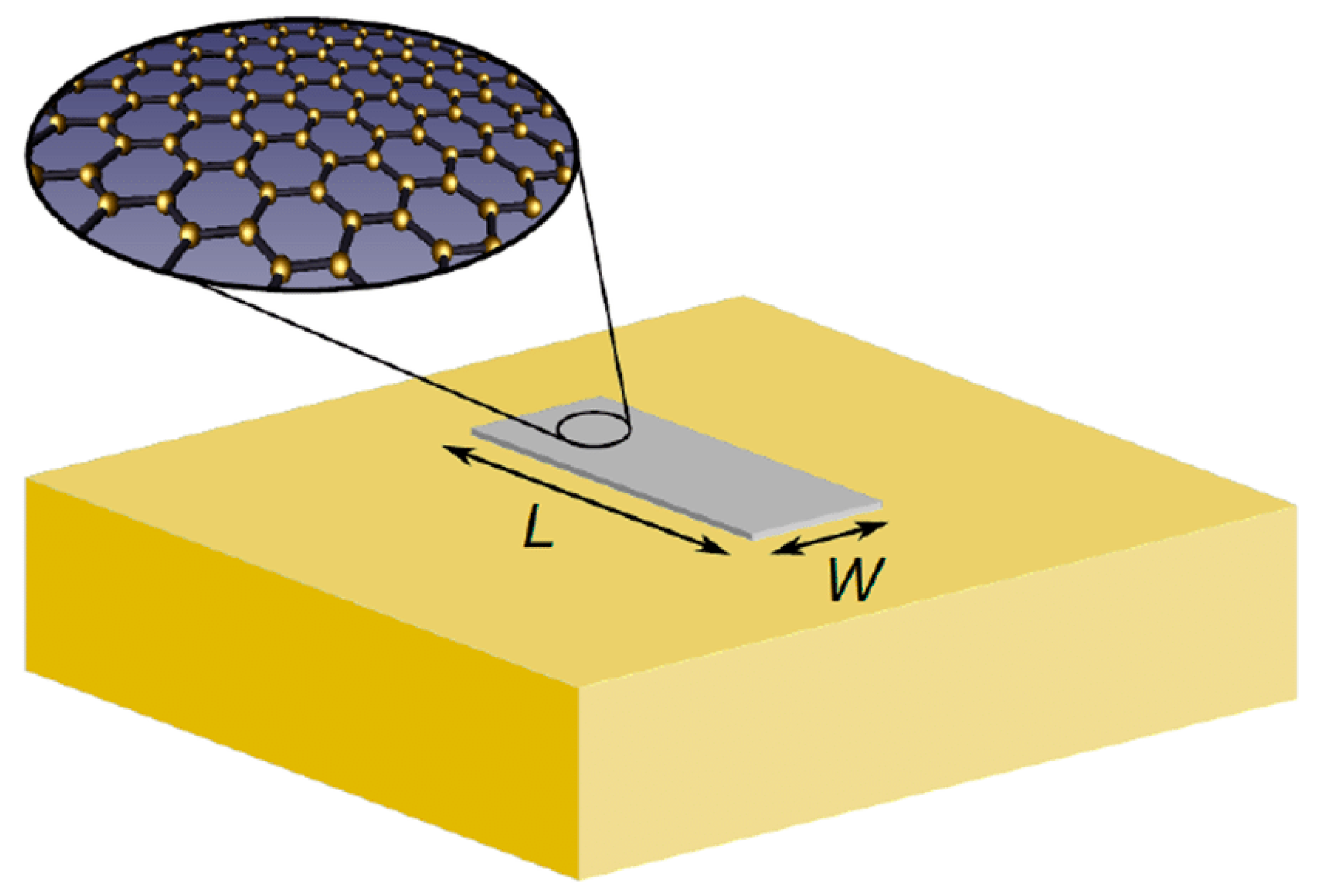

- Nafari, M.; Jornet, J.M. Modeling and Performance Analysis of Metallic Plasmonic Nano-Antennas for Wireless Optical Communication in Nanonetworks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 6389–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadal, S.; Mestres, A.; Iannasso, M.; Paretta, J.C.; Alarcón, E.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A. Evaluating the Feasibility of Wireless Networks-on-Chip Enabled by Graphene. In Proceedings of the NoCArc’14 International Workshop on Network on Chip Architectures, Cambridge, UK, 13–14 December 2014; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Jr.; Wu, H.; Su, Y.; Gao, L.; Sugavanam, A.; Brewer, J.E.; Kenneth, K.O. Communication using antennas fabricated in silicon integrated circuits. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2007, 42, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Tam, S.W.; Pefkianakis, I.; Lu, S.; Chang, M.F.; Guo, C.; Reinmann, G.; Peng, C.; Naik, M.; Zhang, L.; et al. A scalable micro wireless interconnect structure for cmps. In Proceedings of the MobiCom’09 15th annual international conference on Mobile computing and networking, Beijing, China, 20–25 September 2009; pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yin, W.Y.; Liu, Q.H. Performance prediction of carbon nanotube bundle dipole antennas. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2008, 7, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, Y. Sd-mac: Design and synthesis of a hardware efficient collision-free qos-aware mac protocol for wireless network-on-chip. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2008, 57, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science 2009, 324, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jornet, J.; Akyildiz, I. Graphene-based plasmonic nano-antenna for terahertz band communication in nanonetworks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

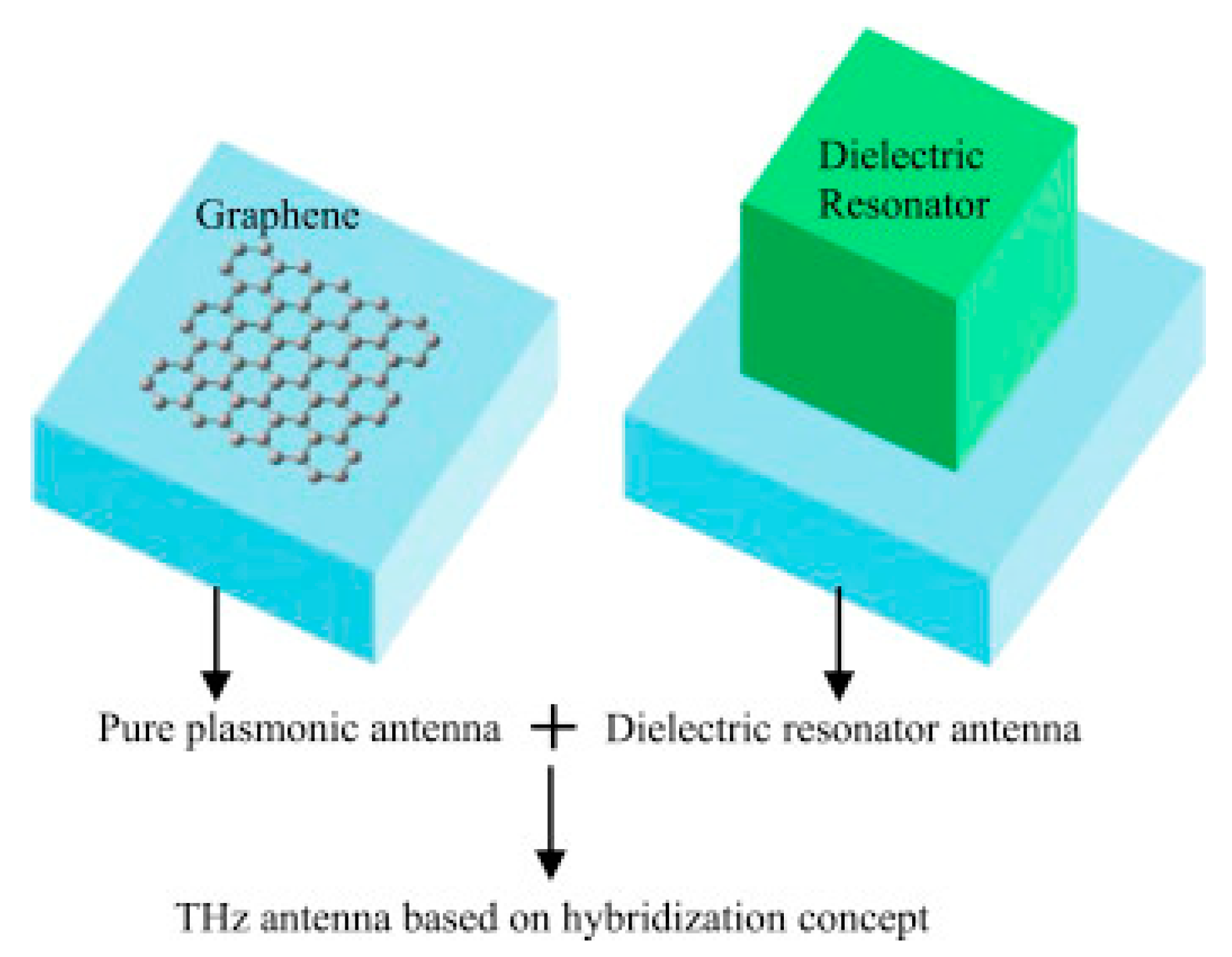

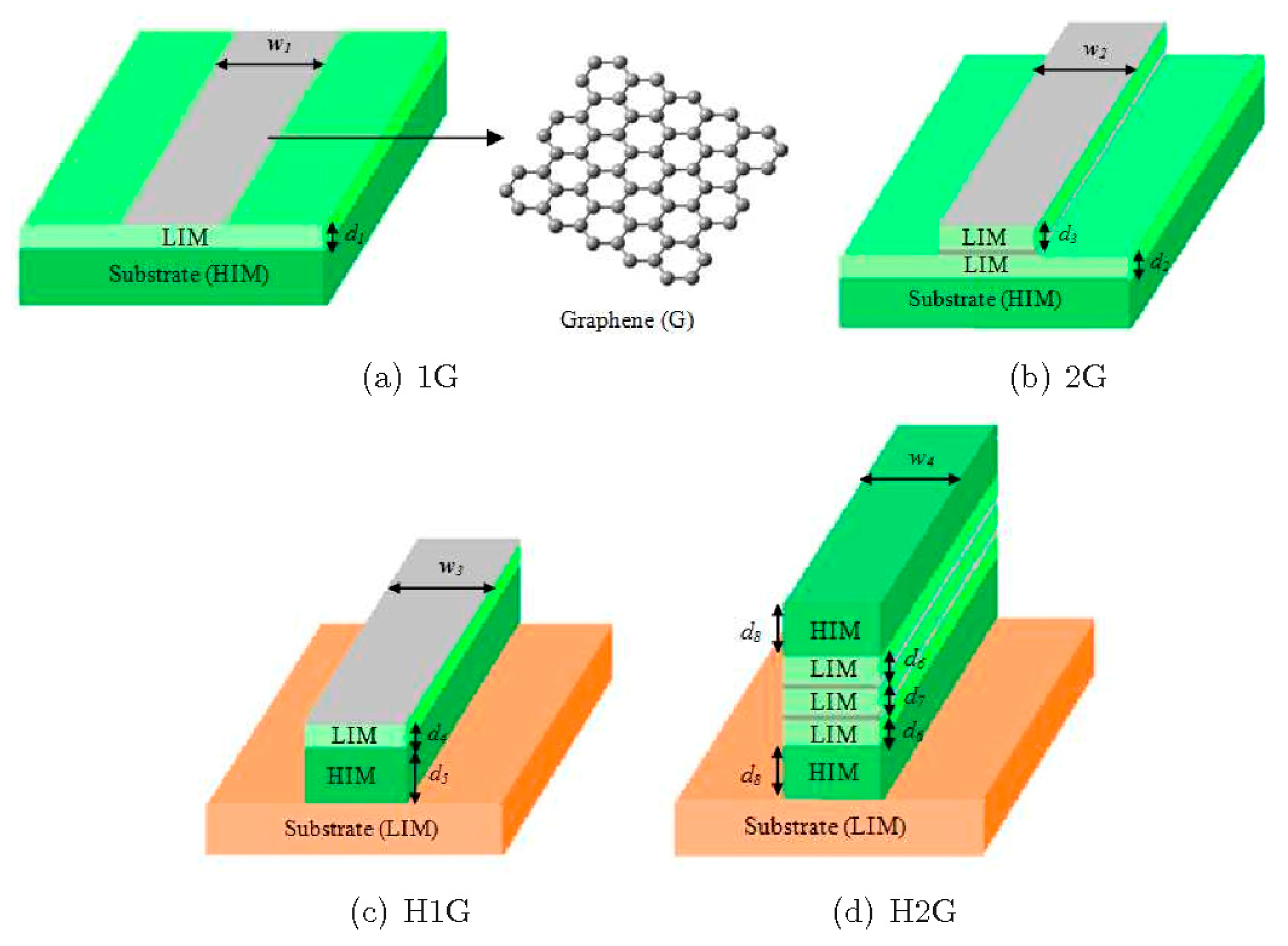

- Hosseininejad, S.E.; Alarcón, E.; Komjani, N.; Abadal, S.; Lemme, M.C.; Bolívar, H.P.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A. Study of Hybrid and Pure Plasmonic Terahertz Antennas Based on Graphene Guided-wave Structures. Nano Commun. Netw. 2017, 12, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.Y.; Guinea, F.; Garcıa-Vidal, F.J.; Martın-Moreno, L. Edge and waveguide terahertz surface plasmon modes in graphene microribbons. Phys. Rev. B-Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 84, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.H.; Chu, H.S.; Li, E.P. Synthesis of highly confined surface plasmon modes with doped graphene sheets in the mid infrared and terahertz frequencies. Phys. Rev. B-Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 125431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Lin, I.T.; Liu, J.M. Extremely confined terahertz surface plasmon-polaritons in graphene-metal structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 071103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Cai, W.; Wang, L.; Xu, J. Surface Plasmon modes in graphene wedge and groove waveguides. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 32432–32440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, R.; Jian, S. The Field Enhancement of the Graphene Triple-Groove Waveguide. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2016, 28, 2649–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Hong, W.; Li, X. A graphene-based hybrid plasmonic waveguide with ultra-deep subwavelength confinement. IEEE J. Lightwave Technol. 2014, 32, 4199–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagnone, M.; Diaz, J.S.G.; Perruisseau-Carrier, J.; Mosig, J.R. High-impedance frequency-agile THz dipole antennas using graphene. In Proceedings of the 2013 7th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Gothenburg, Sweden, 8–12 April 2013; pp. 533–536. [Google Scholar]

- Cabellos-Aparicio, A.; Llatser, I.; Alarcon, E.; Hsu, A.; Palacios, T. Use of THz Photoconductive Sources to Characterize Tunable Graphene RF Plasmonic Antennas. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2015, 14, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Jornet, J.M. Realizing Ultra-Massive MIMO (1024 × 1024) communication in the (0.06–10) Terahertz band. Nano Commun. Netw. 2016, 8, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagnone, M.; Diaz, J.S.G.; Mosig, J.; Perruisseau-Carrier, J. Hybrid graphene-metal reconfigurable terahertz antenna. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest (MTT), Seattle, WA, USA, 2–7 June 2013; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininejad, S.E.; Komjani, N. Waveguide-fed Tunable Terahertz Antenna Based on Hybrid Graphene-metal structure. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2016, 64, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininejad, S.E.; Alarcón, E.; Komjani, N.; Abadal, S.; Lemme, M.C.; Bolívar, H.P.; Cabellos-Aparicio, A. Surveying of Pure and Hybrid Plasmonic Structures Based on Graphene for Terahertz Antenna. In Proceedings of the NANOCOM’16 3rd ACM International Conference on Nanoscale Computing and Communication, New York, NY, USA, 28–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alu, A.; Engheta, N. Wireless at the nanoscale: Optical interconnects using matched nanoantennas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 213902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, D.M.; Taboada, J.M.; Obelleiro, F.; Landesa, L. Optimization of an optical wireless nanolink using directive nanoantennas. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregely, D.; Lindfors, K.; Lippitz, M.; Engheta, M.; Totzeck, M.; Giessen, H. Imaging and steering an optical wireless nanoantenna link. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.L.; da Costa, K.Q. Broadband Wireless Optical Nanolink Composed by Dipole-Loop Nanoantennas. IEEE Photonics J. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, T.; He, J.; Wan, Q. Large scalable and compact hybrid plasmonic nanoantenna array. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 087101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dinesh Kumar, V. Multilayer Hybrid Plasmonic Nano Patch Antenna. Plasmonics 2019, 14, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Ajito, K.; Muramoto, Y.; Wakatsuki, A.; Nagatsuma, T.; Kukutsu, N. Uni-travelling-carrier photodiode module generating 300 GHz power greater than 1 mW. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 2012, 22, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walthera, C.; Fischer, M.; Scalari, G.; Terazzi, R.; Hoyler, N.; Faistb, J. Quantum cascade lasers operating from 1.2 to 1.6 THz. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 131122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.C.; Drouin, B.J.; Maestrini, A.; Mehdi, I.; Ward, J.; Lin, R.H.; Yu, S.; Gill, J.J.; Thomas, B.; Lee, C.; et al. Demonstration of a room temperature 2.48–2.75 thz coherent spectroscopy source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2011, 82, 093105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojefors, E.; Grzyb, J.; Zhao, Y.; Heinemann, B.; Tillack, B.; Pfeiffer, U.R. A 820 GHz SiGe Chipset for Terahertz Active Imaging Applications. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Fransisco, CA, USA, 20–24 February 2011; pp. 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, M.S.; Scalari, G.; Williams, B.; Natale, P.D. Quantum cascade lasers: 20 Years of challenges. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 5167–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.S.; Kumar, S.; Callebaut, H.; Hu, Q. Terahertz quantum-cascade laser at λ ≈ 100 μm using metal waveguide for mode confinement. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jin, Y.; Reno, J.L.; Kumar, S. Large static tuning of narrow-beam terahertz plasmonic lasers operating at 78k. APL Photonics 2017, 2, 026101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Khanal, S.; Reno, J.L.; Kumar, S. Terahertz plasmonic laser radiating in an ultra-narrow beam. Optica 2016, 3, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsuma, T.; Horiguchi, S.; Minamikata, Y.; Yoshimizu, Y.; Hisatake, S.; Kuwano, S.; Yoshimoto, N.; Terada, J.; Takahashi, H. Terahertz wireless communications based on photonics technologies. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizov, F.; Rogalski, A. THz detectors. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2010, 34, 278–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Jian, H.Y.; Pan, B.; Xu, X.; Chang, M.C.F.; Liu, W.; Fetterman, H. CMOS THz Generator with Frequency Selective Negative Resistance Tank. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisic, V.; Leong, K.M.K.H.; Mei, X.; Sarkozy, S.; Yoshida, W.; Deal, W.R. Power Amplification at 0. 65 THz using INP HEMTs. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2012, 60, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knap, W.; Lusakowski, J. Terahertz emission by plasma waves in 60 nm gate high electron mobility transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 2331–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knap, W.; Teppe, F.; Dyakonova, N.; Coquillat, D.; Lusakowski, J. Plasma wave oscillations in nanometer field effect transistors for terahertz detection and emission. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 384205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuji, T.; Watanabe, T.; Tombet, B.; Satou, A.; Knap, W.M.; Popov, V.V.; Ryzhii, M.; Ryzhii, V. Emission and detection of terahertz radiation using two-dimensional electrons in iii-v semiconductors and graphene. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chung, C.J.; Subbaraman, H.; Pan, Z.; Chen, C.T.; Chen, R.T. Design of a plasmonic-organic hybrid slot waveguide integrated with a bowtie-antenna for terahertz wave detection. In Proceedings of the SPIE 9756, Photonic and Phononic Properties of Engineered Nanostructures VI, San Francisco, CA, USA, 14 March 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.C.; Seo, M.-K.; Sarmiento, T.; Huo, Y.; Harris, J.S.; Brongersma, M.L. Electrically driven subwavelength optical nanocircuits. Nature Photon. 2014, 8, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, R. Nanolasers. Ever-smaller lasers pave the way for data highways made of light. Science 2010, 328, 810–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropers, C.; Neacsu, R.C.; Elsaesser, T.; Albrecht, M.; Raschke, M.B.; Lienau, C. Grating-coupling of surface plasmons onto metallic tips: A nanoconfined light source. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 2784–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenbaum, E.; Orenstein, M. Backward propagating slow light in inverted plasmonic taper. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 2465–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryieuski, A.; Malureanu, R.; Biagi, G.; Holmgaard, T.; Lavrinenko, A. Compact dipole nanoantenna coupler to plasmonic slot waveguide. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 1124–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Ren, F.; Wang, A.X. Plasmonic Integrated Circuits with High Efficiency Nano-Antenna Couplers. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Optical Interconnects Conference (OI), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, T.; Muehlbrandt, S.; Ummethala, S.; Schmid, A.; Nellen, S.; Hahn, L.; Freude, W.; Koos, C. Silicon-plasmonic integrated circuits for terahertz signal generation and coherent detection. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbenko, I.V.; Kachorovskii, V.Y.; Shur, M. Terahertz plasmonic detector controlled by phase asymmetry. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 4004–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Diaz, J.S.; Perruisseau-Carrier, J. Graphene-based plasmonic switches at near infrared frequencies. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 15490–15504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correas-Serrano, D.; Gomez-Diaz, J.S.; Perruisseau-Carrier, J.; Alvarez-Melcon, A.A. Graphene-based plasmonic tunable low-pass filters in the terahertz band. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2014, 13, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Argyropoulos, C.; Alu, A. Terahertz antenna phase shifters using integrally-gated graphene transmission-lines. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2013, 61, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuji, T.; Tombet, S.B.; Satou, A.; Ryzhii, M.; Ryzhii, V. Terahertz-Wave Generation Using Graphene: Toward New Types of Terahertz Lasers. Proc. IEEE (Early Access) 2013, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensale-Rodriguez, B.; Yan, R.; Kelly, M.M.; Fang, T.; Tahy, K.; Hwang, W.S.; Jena, D.; Liu, L.; Xing, H.G. Broadband graphene terahertz modulators enabled by intraband transitions. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Yang, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Broadband black phosphorus optical modulator in visible to mid-infrared spectral range. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.05992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, B.; Meng, C.; Fang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tong, L.; Wang, H.; et al. Ultrafast all-optical graphene modulator. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Hu, X.; Yu, X.; Shen, Y.; Li, L.H.; Davies, A.G.; Linfield, E.H.; Liang, H.K.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.F.; et al. Integrated Terahertz Graphene Modulator with 100% Modulation Depth. ACS Photonics 2015, 2, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phare, C.T.; Lee, Y.D.; Cardenas, J.; Lipson, M. Graphene electro-optic modulator with 30 GHz bandwidth. Nat. Photonics 2015, 9, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Ulin-Avila, E.; Geng, B.; Zentgraf, T.; Ju, L.; Wang, F.; Zzhang, X. A graphene-based broadband optical modulator. Nature 2011, 474, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.K.; Aizin, G.; Thawdar, N.; Medley, M.; Jornet, J.M. Graphene-based Plasmonic Phase Modulator for Terahertz-band Communication. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Davos, Switzerland, 10–15 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Mueller, T.; Lin, Y.; Valdes-Garcia, A.; Avouris, P. Ultrafast graphene photodetector. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicarelli, L.; Vitiello, M.S.; Coquillat, D.; Lombardo, A.; Ferrari, A.C.; Knap, W.; Polini, M.; Pellegrini, V.; Tredicucci, A. Graphene field effect transistors as room-temperature Terahertz detectors. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Kikunage, K.; Wang, H.; Sun, S.; Amin, R.; Tahersima, M.; Maiti, R.; Miscuglio, M.; Dalir, H.; Sorger, V.J. Compact Graphene Plasmonic Slot Photodetector on Silicon-on-insulator with High Responsivity. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.00894. [Google Scholar]

- Viti, L.; Politano, A.; Vitiello, M.S. Black phosphorus nanodevices at terahertz frequencies: Photodetectors and future challenges. APL Mater. 2017, 5, 035602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, Z.L.; Yen, S.C.; McDonald, K.F.; Knight, K.; Li, S.; Hewak, D.W.; Tsai, D.P.; Zheludev, N.I. Chalcogenide glasses in active plasmonics. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) Rapid Res. Lett. 2010, 4, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wireless THz Application | *SoA | Beyond *SoA |

|---|---|---|

| NoCs | PCB, 3D, FSO, IR | Graphene based WiNoCs |

| Si photonic/nanophotonics | Hybrid optical-wireless NoCs (plasmonic resonators with dielectric waveguide) | |

| WNSNs (wireless nanosensor networks) | Graphene nanoribbon (GNR)/carbon nanotube (CNT) nanosensors, nanoprocessors, nanoantennas, nanotransceivers | Graphene (GFET) based THz antennas and transceiver parts |

| Nanoscale energy harvesting systems | ||

| Au and Ag plasmon sensors | Nanomemories | |

| Beyond 5G communications | Si photonics based uni-travelling photodiodes (UTC-PDs) and comb sources at mm waves | FSO THz/optical links, |

| Integrated microwave photonics (IMWP) in THz, | ||

| Plasmon or POH modulator (THz/O) | ||

| Graphene multiple-input-multiple-output (MIMO) antennas structures |

| THz Band Transceiver Components | *SoA | Beyond *SoA |

|---|---|---|

| Antenna | Silicon integrated antennas, CNT based antennas, ultra-wide broadband (UWB) and multi-band antennas | Graphene based nanoantennas (patch antenna, dipole, MIMO) |

| Hybrid graphene-dielectric antennas (H2G- two graphene monolayers separated by a thin dielectric) | ||

| Plasmonic antenna with dielectric waveguides (single/dipole loop plasmon nanoantenna, plasmonic horn nanoantennas, single/double/array Vivaldi plasmon antenna/hybrid Plasmon dielectric array) | ||

| Plasmonic nanopatch antenna, with hybrid metal insulator metal (HMIM) plasmonic waveguide | ||

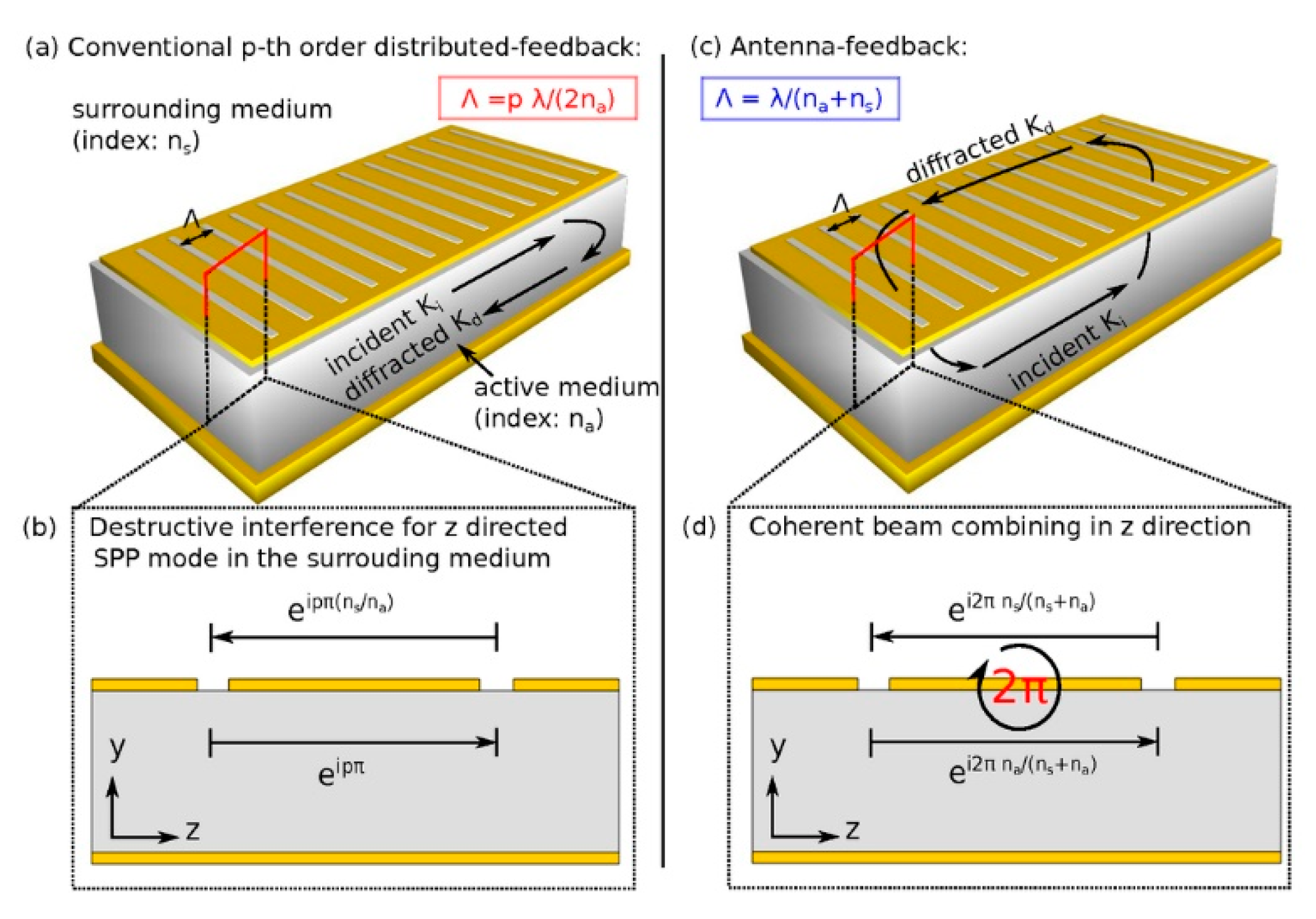

| THz band transmitters | Silicon photonic THz band transmitters (UTC-PDs III/V (InP), QCLs, SiGe-heterojunction bipolar transistors, HBTs) | THz plasmonic lasers (plasmonic quantum cascade lasers (QCLs), THz QCLs with metallic cavities, single-mode metal-clad plasmonic lasers) |

| Hybrid THz transmitters III-V semiconductor based HEMT, enhanced with graphene | ||

| Plasmonic slot waveguides-nanocouplers with on chip sources (nanoLEDs, nanolasers) | ||

| THz band receivers | GaAs Schottky barrier diodes (SBDs), CMOS with high electron mobility transistors (HEMTs) | Hybrid plasmon THz wave detectors (POH slot waveguide with a bowtie-antenna, graphene slot photodetector on SOI) |

| Plasmonic teraFET, graphene-FET | ||

| THz band transceiver package | plasmonic internal photoemission detectors (PIPED) package (Tx, Rx) integrated on si-photonic chip platform | |

| THz band transceiver other parts | Graphene (GFET) based switch, LPF, BPF, phase shifter, graphene THz modulator |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lallas, E. Key Roles of Plasmonics in Wireless THz Nanocommunications—A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245488

Lallas E. Key Roles of Plasmonics in Wireless THz Nanocommunications—A Survey. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(24):5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245488

Chicago/Turabian StyleLallas, Efthymios. 2019. "Key Roles of Plasmonics in Wireless THz Nanocommunications—A Survey" Applied Sciences 9, no. 24: 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245488

APA StyleLallas, E. (2019). Key Roles of Plasmonics in Wireless THz Nanocommunications—A Survey. Applied Sciences, 9(24), 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245488