Abstract

As the effectiveness of conventional wastewater treatment processes is increasingly challenged by the growth of industrial activities, a demand for low-cost and low-impact treatments is emerging. A possible solution is represented by systems coupling solar concentration technology with advanced oxidation processes (AOP). In this paper, a review of solar concentration technologies for wastewater remediation is presented, with a focus on photocatalyst materials used in this specific research context. Recent results, though mostly on model systems, open promising perspectives for the use of concentrated sunlight as the energy source powering AOPs. We identify (i) the development of photocatalyst materials capable of efficiently working with sunlight, and (ii) the transition to real wastewater investigation as the most critical issues to be addressed by research in the field.

1. Introduction

The demand for clean water sources has been rapidly increasing in recent decades, led by industrialization, the expansion of agriculture and, especially, population growth. Access to safe water supplies has thus become an issue of global significance [1]. Moreover, the health risk associated with polluted water resources is projected to become a major global issue within the next few decades [2]. Among the various practical strategies and solutions proposed for more sustainable water management, wastewater reuse and recycling stands out as the most economically-viable and environmentally-friendly [3].

Presently, the most common wastewater treatments are based upon a combination of mechanical, biological, physical and chemical processes such as filtration, flocculation, chemical or biological oxidation of organic pollutants.

A common problem for current technologies is poorly biodegradable organic pollutants, the so-called bio-recalcitrant organic compounds (BROCs). A class of treatments capable of tackling BROCs is known as advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), relying on the formation of highly-reactive transient (e.g., superoxide, peroxide, hydroxyl radical) chemical species that can convert BROCs into more biodegradable compounds or, ideally, into inorganic carbon [4]. Among the most efficient AOPs are those based on hydroxyl radicals OH•, a powerful oxidant. These methods are generally based on the dissociation of hydrogen peroxide in water, either by direct absorption of ultraviolet (UV) photons or by mediation with metal ions (Fe and Co are among the most studied) through Fenton and photo-Fenton reactions [5,6,7]. In addition, and equally or even more important, is the possibility of generating OH• radicals by the interaction, in water, of artificial or natural light with semi-conductors. This process is commonly described as photocatalysis [8].

In recent decades, the photocatalytic degradation of several organic compounds has received growing attention as a water purification process. Irradiating semi-conductors, for example TiO2, in the form of micro- or nano-sized particles, on fixed supports or in aqueous suspensions, creates a redox environment that is reactive towards most organic species [9]. A number of reports have shown that surfactants, pesticides and dyes can be effectively converted into less dangerous products like carbon dioxide and hydrochloric acid. In 1998, the United States Environmental Protecting Agency (EPA) published a detailed list of molecules capable of being degraded by AOPs [10].

In photocatalysis, photons can be seen as reactants and/or co-catalysts, hence playing a critical role in the process. On this basis, considerable research effort has been made since the 90s to employ solar radiation as an abundant, renewable and potentially zero-cost light source. In this approach, solar photons are collected and directed into a photoreactor where they power catalytic reactions. Traditionally, solar collector systems are broadly classified as concentrating or non-concentrating, according to their concentration factor or to the temperature which can be reached by the system [11].

Combining wide versatility, potentially very low cost and the capability of total conversion to non-toxic products, the use of solar-powered AOPs for the treatment of urban and industrial wastewaters is likely the most promising application of AOP technology [12,13].

The application of solar disinfection (SODIS) has also been recently demonstrated on real wastewater samples with the possibility of integrating SODIS technology to an urban wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) [14,15]. Nanofiltration in combination with tertiary processes, including solar photocatalysis, is also the object of considerable research interest; however, it has presented uncertain results [16,17]. Another more material-oriented approach, albeit one that is still at an early stage in terms of literature reports, suggests the use of a combination between a photocatalyst and adsorbents. It is termed “integrated photocatalyst adsorbent” (IPCA), and is based on an adsorbent which has the ability to degrade organic matter in the presence of sunlight [18].

The investigation of different catalyst materials and the comparison of homogeneous vs. heterogeneous catalysis routes are also crucial points, and are hence the object of intense discussion.

This paper presents an up-to-date review of the solar collector systems and of the related catalysts applied to wastewater purification. In particular, we bring together all the collector designs which have been employed for solar photocatalysis to date. To the best of our knowledge, this was done only partially in previous reviews. In addition, we organize the reviewed literature according to the pollutant or pollutants investigated, and to whether the application is to model or real wastewaters. This is a novel angle of analysis; it seeks to highlight the importance of moving towards the investigation of real wastewaters.

Specifically, the first part details solar collector designs and their components. The second part focuses on the catalyst materials employed for solar AOPs. As the development of photocatalysts is a vast field in itself, we decided here to consider only those materials which have already been investigated in combination with a solar collector. Finally, a last section reviews a number of case studies on both model solutions and on real wastewater samples.

2. Solar Collector Systems Employed for Wastewater Treatment

The starting point for the use of solar collectors in wastewater remediation can be traced back to parabolic systems, originally developed for thermal energy applications, and then adapted in 1989 in Albuquerque, NM, USA for water purification. Immediately afterwards, in 1990, a dedicated facility started operations at the Plataforma Solar de Almeria—Spain. Ten years later, dedicated research on wastewater treatments started to be effectively performed [19]. Solar collectors can be concentrating or non-concentrating systems. The former can be classified depending on the principle adopted for focusing sunlight and based on whether they use a fixed or moving receiver [20], while the latter generally consist of flat panels which can be fixed or movable, i.e., following the sun. While in thermal solar applications all wavelengths of the sunlight spectrum are concentrated onto an absorber to produce an increase in temperature, for a solar AOP, the most effective photons are those on the high-energy side of the spectrum, in the UV or near UV range (300–400 nm wavelength), due to the prevalent use of wide band-gap semiconductors as catalyst materials. Wavelengths up to 600 nm are, to date, effectively exploited only by photo-Fenton reactions or by emerging catalyst materials designed ad-hoc for visible light absorption [21]. This is therefore an opportunity and a challenge for the materials science field. The use of light at wavelengths higher than 400 nm would also allow the use of silvered mirrors, which are simple and robust, but which present poor UV reflectance.

In fact, given that, to date, the range between 300 and 400 nm has been considered to be of exceptional importance, conventional silver mirrors have not been considered suitable as reflectors. This is mainly due to their low average reflectance in this wavelength interval, with a minimum at around 320 nm related to an interband transition [22]. Furthermore, the glass covering commonly present on silver mirrors contains iron impurities, which further contribute to reductions in UV reflected radiation.

Mirrors based on aluminum are generally considered a better option when working with processes requiring UV photons [23]. In fact, their reflectance is high (around 93%) and almost constant in the 300–400 nm range. As proposed by Kutscher and Wendelin [24,25], the best reflective surface for solar AOPs should be: (i) efficient in the UV range, (ii) weather resistant, (iii) reasonably cheap. At present, the benchmark solution is based on anodized and electro-polished aluminum surfaces. An available alternative is using aluminum mirrors protected with an acrylic coating [26].

The design of a solar AOP system requires consideration of a number of factors: the mirror materials and shaping, the catalyst, wastewater loading method (batch or once-through), flow type and rates, pressure drops, eventual pretreatment, eventual oxidant loading method, pH control and the use of a tracking system to enhance the direct solar radiation [21]. These criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Design factors for a solar wastewater remediation AOP.

Most existing literature reports are based on different combinations of these factors, giving rise to a variety of configurations [13,19,21]. Some of the main design choices for both concentrating and non-concentrating systems are reviewed in the following sections.

2.1. Concentrating Systems

Concentrating solar collector systems are those which focus incident sunlight through a reflective surface—generally a polished metal, metalized glass or plastic. Solar concentrators can also present tracking systems with one or more axis to follow the sun’s position during the day [27,28,29].

The advantages of concentrating systems are: (1) potentially small reactor tube area, thus allowing for easier handling of the wastewater; (2) a limited reactor area is also more compatible with supported catalysts and turbulent flows, thus avoiding the issue of catalyst sedimentation; (3) the evaporation of volatile compounds can be controlled.

Furthermore, it has been shown that degradation rates are generally improved by an increase of radiation intensity within given limits. This was clearly established for both photo-Fenton reactions and direct photocatalysis for SODIS applications [30,31,32], where a range of linear dependency between rates and irradiance was found and a minimum solar dose identified.

On the other hand, they present disadvantages such as the use of only (or primarily) direct solar radiation, possible high cost, and water overheating [19].

Among the concentrating systems, 5 are of particular interest in the context of wastewater remediation: (1) the parabolic through collectors (PTCs), which concentrate sunlight in a line; (2) compound parabolic collectors (CPCs), a design variant of PTCs; (3) the parabolic dish, designed to focus on a specific spot; (4) Fresnel concentrators, that can be designed to both single spot or line systems; and (5) optical fiber photoreactors, which are presented as a possible solution for reaching remote and difficult-access contaminated water sources.

2.1.1. Parabolic Trough Collectors (PTC)

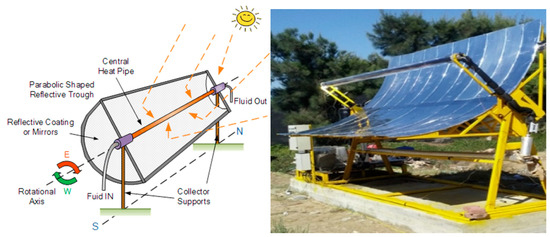

Early solar photoreactor designs for photochemical applications were mounted on parabolic-through-concentrators (PTCs), which were adapted from installations employed for thermal energy generation. PTCs can be defined as parabolic reflective surfaces that concentrate the sun’s radiation on a focal line, where the wastewater flows in a tubular reactor [33]. PTCs are constructed by bending a sheet of reflective or highly polished material, generally reflective silver or polished aluminum, into a parabolic shape. Figure 1 shows the schematic drawing of a PTC and an image of a constructed collector [34]. To increase the efficiency of direct solar radiation collection, the platform can work with one or two motor tracking systems, thereby keeping the aperture plane perpendicular to the incident radiation [13]. PTC applications are different depending on aperture areas, and can be divided in two fields according to temperature range [35]: the first for temperatures in the range between 100 and 250 °C and the second between 300 and 400 °C [36,37,38]. Examples include solar water heating [39], desalination [40,41], and water disinfection [42].

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of a parabolic through collector [43].

Considering the applications of PTC to wastewater purification, early examples consisted of solar thermal parabolic-trough collectors where wastewaters flowed in a borosilicate glass tube placed on the focal line [21,44]. Pyrex or Duran borosilicate glasses were chosen because of the necessity to have low levels of iron impurities. A tubular shape for the photoreactor configuration is considered optimal for sustaining the pressure and flow levels required by circulation systems [19].

2.1.2. Compound Parabolic Collectors (CPC)

A variant of the PTC concentrator described in the previous section is the CPC. With respect to PTCs, they offer the advantage of concentrating on the receiver all the radiation that arrives at the collector within a determined angle of acceptance, thus exploiting also part of the diffuse radiation. The concentration factor (CCPC) of a two dimensions CPC is related to the angle of acceptance, as per Equation (1):

where ϴa is the angle of acceptance, a is the mirror aperture and r is the reactor tube radius. Previous investigations point that a reactor diameter between 25 and 50 mm is optimal [19].

CCPC = 1/sinθa = a/2πr

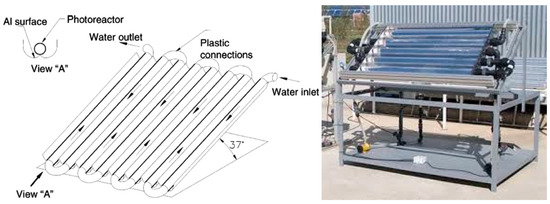

The design of a CPC-based system and an example picture are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing and picture of a compound parabolic collector [27,45].

Several CPC type configurations have been realized and tested by companies such as AO SOL and Energias Renováveis Lda, and have been central to recent research efforts such as Project CADOX, Almeria, Spain [46,47]. Finally, it is worth mentioning an extremely simplified version of the CPC, the compound triangular collector, consisting of two reflective surfaces forming a V-shape. This configuration is of very simple construction and easy maintenance, but it nonetheless recently demonstrated good performance in the treatment of bacterial contaminants in municipal wastewaters [48].

2.1.3. Parabolic Dish Concentrators (PDC)

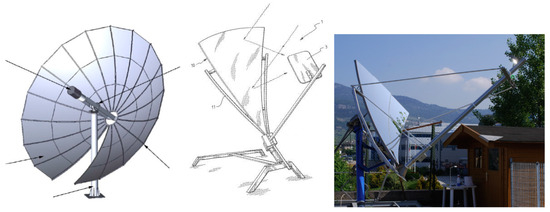

PDCs are widely studied and applied for converting solar energy into electrical or chemical energy, and are accepted as those of highest efficiency in terms of concentration factors. The work of John Ericsson, dating back to the 1880s [49], is recognized as being among first examples of solar energy conversion and the coupling of a PDC to a Stirling engine. A PDC is a type of concentrator which reflects the sun’s rays onto an absorber installed on its spot-like focus. It consists primarily of a support frame equipped with a sun-tracking system, a reflective concave parabolic dish, and an absorber [50]. In this case, tracking the sun is a necessity, since PDCs only work with direct radiation, and a two-axis tracker is commonly employed.

PDCs offer the possibility of being installed in hybrid operation plants in combination with distinct types of solar concentrators [51]. The solar dish system can achieve, if temperature is of interest, high values due to high concentration factors. Figure 3 presents a schematic drawing and an image of a parabolic module in use in our laboratories. This collector is based on an innovative process to manufacture parabolic mirrors, resulting in potentially very low production costs [52,53].

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing and picture of a parabolic dish [52,53].

In solar wastewater purification, the selection of a PDC is motivated by specific needs. Being the most effective concentrators—reaching concentration ratios higher than 2000 suns—they can provide an advantage in cases where a very high photon density and/or thermal processes enhance pollutant degradation, for example, when the rapid abatement of a high content of pollutant is needed [54].

2.1.4. Fresnel Solar Concentrators

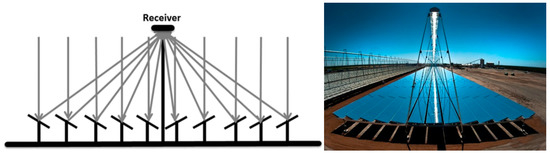

Fresnel solar collectors have been developed and applied for solar energy production, and can be found in both a line or point-focus design. They can work in two basic configurations exploiting either mirrors or lenses to produce the concentration effect. Usually they are ground-mounted mirrors or lenses with flat or nearly flat surfaces tracking the sun and concentrating onto a focal receiver which, for wastewater treatment, is usually of tubular design and is equipped with secondary reflectors [55].

Compared to PTCs, Fresnel configurations offer two distinct advantages: (1) the receiver is fixed and usually with a larger collection area, which can lead to a simpler photoreactor design; (2) mirrors can be smaller and flat or nearly flat, and are thus of simpler and cheaper fabrication. However, due to a greater distance between the receiver and the mirror array, they suffer from lower optical efficiency and are particularly prone to tracking errors [56].

Figure 4 presents the schematic drawing and an actual installation of Fresnel reflectors. This example shows the most common configuration, with evenly-placed, identical mirrors, a convenient design in terms of simplicity, but not necessarily the most efficient [57].

Figure 4.

Schematic drawing of a Fresnel lens receiver [56].

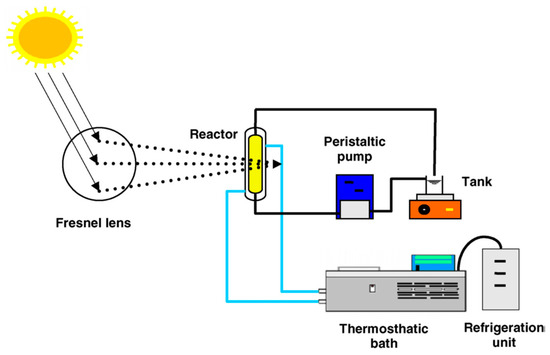

A few applications to wastewater purification can be found in the literature. For example, Fresnel transmitting concentrators, which employ lenses instead of mirrors, were recently investigated. The lenses were made of an acrylic material with a transmittance of 0.92 in the range 400–1100 nm [58,59]. Despite the drawback of difficulties of concentrating UV light (<400 nm), results evidenced a possible reasonable option if used with low costs catalysts to accelerate the degradation of orange II and blue 4 in water models, as a comparison of solely using direct solar radiation. A scheme of Fresnel lens transmitter concentrator is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fresnel lens transmitter concentrator scheme [60].

2.1.5. Optical Fiber Photoreactors

Optical fiber photoreactors have recently been studied for water remediation. The basic principle here is to use optical waveguides, usually in the form of optical fibers, to convey photons into the bulk of a wastewater. An interesting possibility is that of using a photocatalyst directly supported on the waveguides to achieve very high surface area to volume ratios. Some reports show values even higher than for a conventional photoreactors with suspended photocatalysts [61]. The use of optical fibers as waveguides has been investigated mostly with artificial light [62,63]. Extending the concept for use with sunlight would be much more complicated, with the need for a very accurate reflectors/tracking system to compensate for the sun’s movement.

The main advantage of this design is that the distance between the light collection system and the photoreactor can be great and non-linear, thanks to the properties of optical fibers. This would make it possible to reach otherwise inaccessible wastewater reservoirs, for example within buildings or subterranean reservoirs [64]. To date however, its complexity and low efficiency makes this design impractical [33].

2.2. Non-Concentrating Systems (NCC)

Non-concentrating collectors usually consist of flat mirrors oriented to the equator line with a predetermined inclination angle depending on the installation place latitude. They can be static or movable systems, and are generally on a single axis.

Their main advantages are: (1) simple design and low fabrication cost when compared to curved mirrors [65], and (2) they work with both direct and diffuse radiation. Also, they present high optical and quantum efficiency but usually do not heat water efficiently, which can be an advantage depending on the particular application. The main drawback is that they are generally designed for laminar flows, for which mass transfer rates are known to be suboptimal [19]. Among the non-concentrating systems, two deserve particular attention: (1) inclined plate collectors (IPC) and (2) water-bell photoreactors.

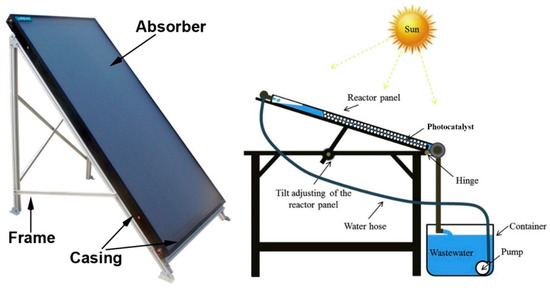

2.2.1. Inclined Plate Collectors (IPC)

Inclined plate collectors (IPC) are flat or corrugated panels over which a thin (typically < 1 mm) laminar flow (usually 0.15–1.0 L/min) of wastewater is sustained. It is probably the simplest available design and offers the advantage of a large surface to support the photocatalyst material, in a configuration known as “thin film fixed bed reactor” (TFFBR). It is to be noted that water heating is not an issue with this design, with temperature typically between 70 and 95 °C [66]. IPCs are considered to be particularly suitable for small-scale applications [67]. Figure 6 presents an image and a scheme of an IPC.

Figure 6.

Examples of inclined plate collectors [68].

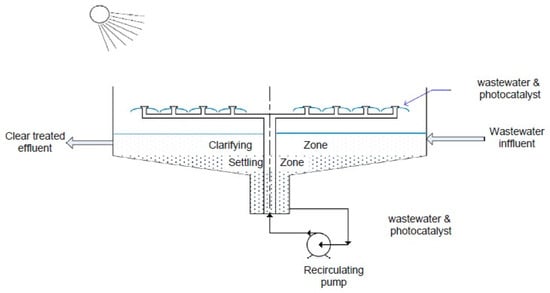

2.2.2. Water-Bell Photoreactor

This type of photoreactor, as shown in Figure 7, is similar in general design to the IPC reactor. The main differences are as follows: (1) the water film is generated by ejecting the fluid through nozzles with the shape of a water-bell, and (2) the photocatalyst is dispersed in powder form in the liquid phase. As positive points, it permits a turbulent flow [69,70] and avoids sedimentation of the catalyst due the constant pumping of liquid through the nozzles [71]. High flow rates can provide intense mixing and avoid dead zones in the system. On the other hand, the advantages provided by supported photocatalysts, as in the IPC design, are lost.

Figure 7.

Schematic drawing of a water-bell photoreactor [72].

3. Advanced Oxidation Processes and Photocatalysis

AOPs are commonly defined by the chemistry and chemical engineering community as water treatments aimed at the removal of pollutants via oxidation by highly-reactive radicals, such as the hydroxyl (OH•) or others (e.g., superoxide, peroxide, sulphate). As we are interested here in processes which can be activated by sunlight, we will limit this review to those involving photocatalysis. In wastewater remediation, the most common process employs hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as the hydroxyl radicals source, activated by UV light. Although oxidation reactions by OH• have been known for more than a century, with the use of Fenton’s reagent in analytical chemistry, the application to wastewater remediation was only considered when evidence of OH• generation in “sufficient quantity to carry out water purification” was given in the late 1980s [73]. Even though AOPs are of special interest for several applications, among which aromatics and pesticides degradation in water purification processes [74], oil derivatives, and volatile compounds [75], they have not yet been employed for large-scale commercial use. AOPs offer important advantages in water remediation, such as the possibility to effectively eliminate organic compounds in the aqueous phase, rather than collecting or transferring pollutants into another phase. Indeed, the contaminants can, in principle, be converted by complete oxidation into inorganic compounds, such as carbon dioxide; this process is called mineralization. Also, OH• can, in principle, react with almost every organic aqueous pollutant without discriminating, potentially targeting a wide variety of compounds. A notable exception is that of Perfluorinated compounds, which are not attacked by OH• radicals due to the stability of the C-F bond [76]. Some heavy metals can also be precipitated as M(OH)x [77]. AOPs currently have a number of serious drawbacks, affecting cost and limiting their large-scale application. For example, a constant input of reagents is usually necessary to keep an AOP operational, because the quantity of hydroxyl radicals in solution needs to be high enough to react with all the target pollutants at useful rates. Scavenging processes can occur in the presence of species which react with OH radicals without leading to degradation, for example, bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) [78] and chlorides [79] should be removed by a pre-treatment or the AOPs will be compromised. In particular, the interference role of bicarbonate, chloride and dissolved silica anions has been recently studied in depth [80,81,82]. Finally, most existing processes rely on TiO2 as the catalyst material. Although it offers important advantages in terms of stability, robustness and catalytic activity, it also has the serious limitation of requiring activation by UV light [83]. As such, it is mostly employed with artificial UV-sources, which are expensive, have short operational lifetimes, and require a high energy input.

For these reasons, it is not economically reasonable to use only AOPs to treat large amounts of wastewater, but AOPs can be conveniently integrated with conventional treatments as a final or intermediate step [84]. In this context, the use of solar radiation to promote AOPs could contribute to greatly reducing costs by relying on a free and renewable source of photons, even if the cost problems mentioned above must be mitigated in order to have an efficient and competitive water purification technology. This possibility, along with increasing efforts towards the implementation of water reuse worldwide, are currently accelerating research towards the implementation of large-scale AOPs [4].

3.1. Principles of Solar Photocatalysis

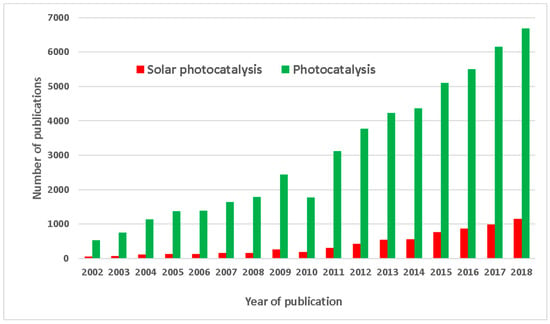

Solar photocatalysis currently plays a minor role, since the growth of research focusing on solar systems applied therein has shown a smaller increase compared to overall photocatalysis research, as demonstrated on Figure 8. This information points to the opportunity to dedicate efforts to this clean technology connected to the abundant solar energy source.

Figure 8.

Publications on photocatalysis compared to those on solar photocatalysis. Data from Scopus comparing “photocatalysis” with “solar AND photocatalysis” as search terms within the “article title, abstract, keywords” search field.

Major types of photocatalysis include heterogeneous photocatalysis, where the catalyst and substrates are in different phases, and homogeneous photocatalysis, where they are in the same phase. We adopt this classification for the following sections.

3.1.1. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis

In heterogeneous photocatalysis processes, the catalyst is generally a semiconductor material activated by absorption of UV or UV-Visible photons. Several semiconductors have been investigated as catalysts, such as TiO2, ZnO, Fe2O3, CdS, GaP, Co3O4, ZnS, etc. Among these, TiO2 has received the most investigation efforts since its good photocatalytic properties under UV irradiation were already known in the early 1970s. However, novel types of catalysts focused to solar applications are rapidly emerging, especially those which are able to efficiently absorb visible light.

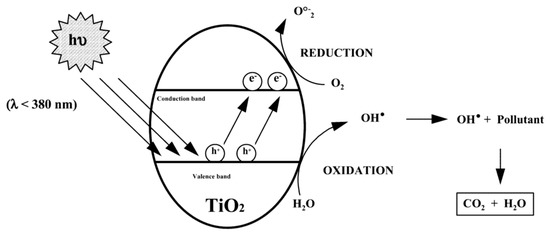

Heterogeneous photocatalysis by semiconductors can be explained in the framework of the band theory for the electronic structure of solids. In Figure 9 the first step is shown, where an electron (e−) in the valence band (VB) is excited to the vacant conduction band (CB) by absorption of a photon of energy hv (see Figure 9) equal to or greater than its optical band gap, leaving a positive hole (h+) in the VB. The excited electrons can reduce available acceptor species, such as oxygen in proximity of the surface, while holes are often powerful oxidants. The photo-generated electrons and holes can thus drive redox reactions with species for which the involved redox potentials are an appropriate match. However, the electrons and holes can also recombine without participating in any redox process, in a competing deactivation event. This is a major issue in the design of materials, and is the reason why the time scale of the recombination process must be kept as large as possible.

Figure 9.

General mechanism of the heterogeneous photocatalysis [8].

In the case of TiO2 photocatalysis in water with UV photons of energy ≥3.2 eV for anatase and 3.0 eV for rutile (corresponding to about 387 and 413 nm wavelength respectively), photo-generated electron-hole pairs at the solid-liquid interface can promote redox reactions with adsorbed water and dissolved oxygen. This process results in the formation of OH• and O2− radicals respectively, which are powerful oxidant species capable of reacting with most organic substances. The two most common configurations for heterogeneous photocatalytic reactors are: (1) reactors where the photocatalyst is in powder form suspended in water, and (2) reactors where the photocatalyst is immobilized on a surface. The first configuration is more explored, due to the simplicity of synthesis methods for powders; however, it needs an additional separation step, generally sedimentation and/or filtration, to recover the catalyst material. In the case of TiO2, commercial products such as P25 and P100 from Degussa are the most commonly-employed in the literature. Catalyst separation and recovery is a major drawback for large-scale applications [1]; thus, it is possible to identify here an open space on the research field aimed at the immobilization of the photocatalyst. This is highlighted by emerging manufacturing technologies, as exemplified by the use of pulsed laser deposition (PLD) for the production of nanocatalysts with controlled properties [85,86]. Discussions highlighting the use of TiO2 catalysts with sunlight on PTR and IPC reactors can be found in the literature [87,88]. Also, advances in photocatalyst immobilization for TiO2, to be used with concentrated sunlight, present alternatives as mesoporous clays, nanofibers, nanowires, nanorods, membranes and surface doping modifications [1]. The possibility to produce glasses or polypropylene tubes with supported TiO2 has also been reported [45]. In practice, however, novel applications of TiO2 have been hindered due to their wide optical band gaps allowing only little or no absorption of visible-light [89,90]. The use of doping has been extensively investigated with the goal of increasing the catalyst absorption in the visible range, among which modifications of TiO2 by W [91], Pt [92], N, V and V-N [93], Cu and N [94], Co and B [95], and Ag [96] showed promising results for the photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds. Many studies have also been devoted to the design of other metal oxide photocatalyst materials, such as perovskite-type oxides, which can work under visible light illumination [18,97,98]. Other catalysts investigated for wastewater purification with sunlight are Bi2WO6 and Ag-BiVO4, for their absorption closer to the visible range (420 nm) [99]. In a theoretical work, density functional theory (DFT) calculations explored the modification of a β-Bi2O3 photocatalyst with 32 elements to design visible-light-responsive photocatalysts. Based on this, a series of photocatalysts were identified as good candidates for the reduction of chlorinated organic compounds in water [100]. Recently, Co3O4 hierarchical urchin-like structures were produced by PLD and tested on model dyes, raising great interest in the synthesis of hierarchical 3D nanostructures for applications in water purification [85]. Iron oxide-based nanostructures have also been fabricated by PLD and studied for photocatalytic water purification [101]. Other catalysts such as ZnO, SnO2, WO3, and ZnS have also been reported which can operate either via the reductive pathway (ZnS), the oxidative one (SnO2 and WO3) or both (ZnO) [102,103].

An interesting study employed volcanic ashes in a solar photocatalytic reactor. The volcanic ashes are rich in titanomagnetite, labradorite, augite and ferrous magnesium hornblende capable of performing photocatalysis in the visible-NIR ranges [104]. Reports of novel materials focusing on visible light response catalysts are rapidly emerging and are increasingly successful. Their application to solar concentration for wastewater purification appears to represent an interesting opportunity to advance the field. Table 2 below shows a selection of references implementing the design strategies discussed above.

Table 2.

Selected references for catalyst materials. Selection is based on two criteria: materials developed for visible light absorption and materials introducing an advancement over benchmark TiO2.

3.1.2. Homogeneous Photocatalysis

In the homogeneous photocatalysis process, important efforts were devoted to the investigation of the Fenton reaction in an aqueous solution containing metal ions and hydrogen peroxide, capable of providing hydroxyl radicals. When UV/visible radiation (wavelength ≤ 600 nm) is introduced in the process, it becomes catalytic; this is known as “photo-Fenton” [7,111,112]. In the photo-Fenton reaction, the metal ion initially reacts with the H2O2 added to the contaminated water, producing OH• radicals (Equation (2)):

Metal2+ + H2O2 → Metal3+ + OH− + OH•

Metal3+ + OH− + hv → Metal2+ + OH•

The absorption of a photon (Equation (3)) then not only restores the initial Metal2+, the crucial catalytic species for the Fenton reaction, but also produces additional radicals that can contribute to the oxidation of organic pollutants [113].

Though less interesting from an industrial point of view due to the difficulty of separating and recovering the catalyst, a photo-Fenton process in the homogeneous route has been recently demonstrated for SODIS technology, using ethylendiamine-N′,N′-disuccinic acid as a complexing agent to prevent iron precipitation as ferric hydroxide [114].

3.2. Homogeneous Versus Heterogeneous Photocatalysis

Among the major solar photoreactor system design issues is whether to use a homogeneous route with a dissolved catalyst or a heterogeneous one with a suspended or supported catalyst. This decision is greatly affected by the availability of facile and cost-effective fabrication methods. A large part of the investigations performed so far have used suspended particles in the contaminated water, which, as with the case of a dissolved catalyst, demands a final extra step to separate and recover the catalyst. A solution to this problem is the use of supported catalyst configurations, but this has, to date, been hindered by higher costs due to more complex synthesis procedures. Thus, research efforts on improved manufacturing techniques, such as the use of PLD, will likely offer possible solutions to this issue [85,101,115,116,117,118,119].

A supported-catalyst design also needs to take into account several additional problems. As the catalyst dispersion is not optimal, the greatest possible surface area is needed to ensure a good contact between active sites and target substrates, and an effective irradiation geometry must be identified. A good adhesion with the supporting material is also critical, as it dictates the capability of withstanding the mechanical wear from the water flow, and thus, the durability and operational lifetime of the catalyst coating. All these issues can, however, be addressed by careful design and improvements in coating technology.

Overall, the heterogeneous route to photocatalytic water treatments with supported semiconductors is a more promising technology when compared to its suspended catalyst counterpart or to the homogeneous route, mainly due to the necessity of easy industrial handling and replacement of the materials.

4. Wastewaters

Since investigations dedicated to water purification with the use of sunlight began, several types of pollutants have been investigated. These have generally been model compounds, while real wastewaters, due to their greater complexity, are still less explored. In the following sections, papers investigating important model and real wastewaters are presented in tables organized by the main class of pollutant considered.

4.1. Model Pollutants

In the initial studies of the solar concentration for wastewaters research field, several types of model pollutants were investigated using concentrated sunlight and AOPs [120]. The United States Environmental Protecting Agency (EPA) made an inventory of more than 800 molecules that can be degraded by advanced oxidation processes [10]. In Table 3, works that investigated BROCs from the industrial general chemical products sector are presented. The investigations collected were performed from 1999 until today, and are representative of the importance of solar collectors to the wastewater purification field. Among the pollutants tested on the water models, substances such as phenols, amines, gaseous toluene and acetaldehyde, detergents, trichloroethylene, phenolate, diverse acids and phosphates deserve attention. In terms of the solar collector employed, special emphasis was devoted to the PTC and CPC configurations (12 reports), IPC (5 reports), optical fiber (2 reports), and PDC (1 report). In terms of catalysts, all the investigations primarily reported on the use of TiO2 as a catalyst material, with variations in terms of the supporting system, doping element and particle structure. As a solid catalyst, TiO2 was consequently employed in the heterogeneous route for catalysis.

Table 3.

BROCs model wastewaters (Industrial general chemical products).

Table 4 presents the published papers dedicated to the investigation of model waters containing dyes as the main pollutant. The first studies were reported in 1994 and continue to receive interest to the present day. Dyes such as methyl-orange, Remazol red B, rhodamine, indigo carmine, methylene blue, and reactive black 5, among others, were studied by employing either CPC or IPC solar collectors. Also, 3 investigations were performed using the homogeneous route with ferrous salts solutions, and the majority with the heterogenous one.

Table 4.

BROCs model wastewaters (Dyes).

Table 5 instead presents the use of solar photocatalysis, mostly under the heterogenous route with IPC and CPC solar collectors, to investigate the degradation of pesticides as model pollutants. In this segment of pollutants, investigations have gained attention since the year 2000. Eight miscellaneous pesticides (ethoprophos, isoxaben, metalaxyl, metribuzin, pencycuron, pendimethalin, propanil and tolclofos-methyl) were studied. Initial investigations on this sector have paved the way for further research on real water sources from extensive agriculture areas.

Table 5.

BROCs model wastewaters (Pesticides).

A last BROC contaminant reported in the literature was a pharmaceutical product, as reported in Table 6. In 2005, a CPC solar collector using commercial P-25 TiO2 as the catalyst and heterogeneous photocatalysis was utilized to investigate the degradation of the antibiotic Lincomycin.

Table 6.

BROCs model wastewaters (Pharmaceuticals).

In another field of application of solar collectors applied for wastewater purification, solar disinfection (SODIS) was employed to study the removal of bacteria as E. Coli, faecalis and Salmonella and fungi, such as fusarium spores as shown in Table 7. Investigations were mostly developed with CPC solar collectors. Both heterogeneous and homogeneous routes are represented, with a prevalence of TiO2 catalyst for the former and of ferrous solutions for the latter.

Table 7.

SODIS model wastewaters (Bacteria and Fungi).

4.2. Real Pollutants

The investigation of real wastewaters samples has taken place mainly in the last decade. Anyhow, the increasing importance of this approach demonstrates a constant switch from model investigations to real wastewater sources with the aim of solving the critical situation of pollution worldwide. Table 8 shows real industrial effluents already investigated such as olive mill wastewater, effluents from the beverage industry, micropollutants in municipal effluents, metallic wastes and surfactant-rich industrial wastewaters, mostly with CPC solar collectors. Both heterogeneous and homogeneous routes were used.

Table 8.

Real wastewaters (Industrial general chemical products).

Residual dyes from the textile industry were studied in 2015 as shown in Table 9 under homogeneous route using CPC solar collectors and ferrous solutions as catalyst.

Table 9.

Real wastewaters (Dyes).

Table 10 shows investigation of real wastewater sources contaminated with pesticides containing Chlorpyrifos, lambda-cyhalothrin and diazinon using CPC or IPC solar collectors, employing homogeneous and heterogeneous photocatalysis routes.

Table 10.

Real wastewaters (Pesticides).

Municipal wastewaters contaminated with pharmaceuticals were treated and results are reported on the publications in Table 11. Among the contaminants, presences of acetaminophen, antipyrine, atrazine, carbamazepine, diclofenac, flumequine, hydroxy biphenyl, ibuprofen, isoproturon, ketorolac, ofloxacin, progesterone, sulfamethoxazole and triclosan were investigated. Novel Fe-TiO2 composite catalysts with the objective of performing both photocatalysis and photo-Fenton have been studied for the treatment. Their degradation performances were evaluated in a CPC reactor under the homogeneous and heterogeneous route.

Table 11.

BROCs real wastewaters (Pharmaceuticals).

In terms of SODIS, as shown in Table 12, application to real wastewater sources, municipal effluents were mostly used to investigate the inactivation of bacteria and fungi using the homogeneous and heterogeneous routes. CPC solar collectors were used and ferrous salts and TiO2 were used as catalysts.

Table 12.

SODIS real wastewaters (Bacteria and Fungi).

All the analyzed studies present relevant information about degradation rates and the processes involved in the use of solar light for the degradation of pollutants in wastewaters. In particular, a relevant quantity of pollutants were tested and the development of low-cost solar systems evolved. Also, it is observed that TiO2 is a very well-established catalyst for use in solar wastewater degradation, but new catalysts and possible cost reductions offer interesting opportunities for research.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Although solar water treatments have produced significant interest in research, they have not yet reached commercialization; there are only a few examples of medium to large-scale solar wastewater processing plants in industry. However, recent literature results demonstrate that solar wastewater treatment has the potential to be successfully employed both as a cheaper and more environmentally-friendly alternative to conventional processes, or integrated in existing plants, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing operating costs. However, further research towards industrialization is needed. Two directions emerge as particularly promising: advances in materials science towards immobilized photocatalysts, which can effectively use sunlight, and switching to the investigation of real, rather than model, wastewaters.

Regarding the former, photocatalysts working with UV-visible light would make it possible to better harness sunlight and ease the design requirements for solar collectors and photoreactors. For example, by eliminating the need for UV radiation, it would be possible to use conventional mirrors, which are significantly less expensive and more durable than UV-reflecting mirrors.

Regarding wastewaters, investigations which initially began with water models have turned to real wastewater sources in recent years. These are much more complicated samples, generally containing a variety of species which can interfere with the treatment. This complexity needs to be tackled by directed research efforts, particularly by the chemistry and chemical engineering community, in order to progress towards industrial application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.F., M.O., A.M. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.F.; writing—review and editing M.O., A.M.; supervision A.Q. and A.M.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Trento, project ERICSOL, in a collaboration between the industrial engineering and physics departments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Polo-López, M.I.; Mosteo, R.; Ormad, M.P.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P. Disinfection of real and simulated urban wastewater effluents using a mild solar photo-Fenton. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 150–151, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwal, A.; Chaudhary, R. Feasibility study for the treatment of municipal wastewater by using a hybrid bio-solar process. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 177, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.R.; Nunes, O.C.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Silva, A.M.T. An overview on the advanced oxidation processes applied for the treatment of water pollutants defined in the recently launched Directive 2013/39/EU. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrini, O.; Oliveros, E.; Braun, A.M. Photochemical processes for water treatment. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 671–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, G.; Bauer, R.; Heisler, G. The photo-Fenton reaction—An effective photochemical wastewater treatment process. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1993, 73, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwi, J.; Pulgarin, C.; Peringer, P. Effect of Fenton and photo-Fenton reactions on the degradation and biodegradability of 2 and 4-nitrophenols in water treatment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 1994, 3, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, D.; Malato, S. Solar photocatalysis: A clean process for water detoxification. Sci. Total. Environ. 2002, 291, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavello, M. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis; Wiley Series in Photoscience & Photoengineering; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-662-48717-4. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Design Manual: Constructed Wetlands and Aquatic Plant Systems for Municipal Wastewater Treatment; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Rabl, A. A Solar Collectors and Their Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1985; ISBN 978-0-195-0354-69. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, J.; Buckles, J.D.; Moeller, J.R. the Role of Solar Ultraviolet Radiation in ‘Natural’ Water Purification. Photochem. Photobiol. 1976, 24, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasiano, D.; Marotta, R.; Malato, S.; Fernandez-Ibañez, P.; Di Somma, I. Solar photocatalysis: Materials, reactors, some commercial, and pre-industrialized applications. A comprehensive approach. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 170–171, 90–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Alfaro, S.; Rueda-Márquez, J.J.; Perales, J.A.; Manzano, M.A. Combining sun-based technologies (microalgae and solar disinfection) for urban wastewater regeneration. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukkasi, S.; Terdthaichairat, W. Improving the efficacy of solar water disinfection by incremental design innovation. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Schmid, A.; Tarpani, R.R.Z.; Miralles-Cuevas, S.; Cabrera-Reina, A.; Malato, S.; Azapagic, A. Environmental assessment of solar photo-Fenton processes in combination with nanofiltration for the removal of micro-contaminants from real wastewaters. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, H.; Ali, W.; Haydar, S.; Tesfamariam, S.; Sadiq, R. Modeling exposure period for solar disinfection (SODIS) under varying turbidity and cloud cover conditions. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, N.; Aziz, F.; Jamaludin, N.A.; Mutalib, M.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Salleh, W.N.; Jaafar, J.; Yusof, N.; Ludin, N.A. A review of integrated photocatalyst adsorbents for wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7411–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.M.; Gálvez, J.B.; Rubio, M.I.M.; Ibáñez, P.F.; Padilla, D.A.; Pereira, M.C.; Mendes, J.F.; De Oliveira, J.C. Engineering of solar photocatalytic collectors. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharoon, D.A.; Rahman, H.A.; Omar, W.Z.W.; Fadhl, S.O. Historical development of concentrating solar power technologies to generate clean electricity efficiently—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 996–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichat, P. Photocatalysis and Water Purification: From Fundamentals to Recent Applications; Wiley Series in New Materials for Sustainable Energy and Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-352-733-1871. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, Y.-C.; Søndergaard, T.; Skovsen, E.; Gurevich, L.; Pedersen, K.; Pedersen, T.G. Pore size dependence of diffuse light scattering from anodized aluminum solar cell backside reflectors. Opt. Express 2013, 21, A84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, G.J.; Govindarajan, R. Ultraviolet Reflector Materials for Solar Detoxification of Hazardous Waste. Proc. SPIE 1991, 1536, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelin, T. Outdoor Testing of Advanced Optical Materials for Solar Thermal Electric Applications; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 1992.

- Kutscher, C.; Davenport, R.; Farrington, R.; Jorgensen, G.; Lewandowski, A.; Vineyard, C. Low-Cost Collectors. System Development Progress Report; Solar Energy Research Institute: Golden, CO, USA, 1984.

- Alanod Aluminium-Veredlung GmbH & Co. Available online: https://www.alanod.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Tanveer, M.; Tezcanli Guyer, G. Solar assisted photo degradation of wastewater by compound parabolic collectors: Review of design and operational parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullikkas, A.; Kourtis, G.; Hadjipaschalis, I. Parametric analysis for the installation of solar dish technologies in Mediterranean regions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2772–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.V.; Link, H.; Bohn, M.; Gupta, B. Development of solar detoxification technology in the USA—An introduction. Sol. Energy Mater. 1991, 24, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gómez, E.; Martín, M.M.B.; García, B.E.; Pérez, J.A.S.; Ibáñez, P.F. Wastewater disinfection by neutral pH photo-Fenton: The role of solar radiation intensity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 181, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichel, C.; Tello, J.; de Cara, M.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P. Effect of UV solar intensity and dose on the photocatalytic disinfection of bacteria and fungi. Catal. Today 2007, 129, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndounla, J.; Kenfack, S.; Wéthé, J.; Pulgarin, C. Relevant impact of irradiance (vs. dose) and evolution of pH and mineral nitrogen compounds during natural water disinfection by photo-Fenton in a solar CPC reactor. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 148–149, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braham, R.J.; Harris, A.T. Review of major design and scale-up considerations for solar photocatalytic reactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 8890–8905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, S.A.; Gulhane, N.P. Optical evaluation of compound parabolic collector with low acceptance angle. Opt. Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2017, 149, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, A.; Rojas, E.; Pérez, M.; Silva, R.; Hernández-Escobedo, Q.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. A parabolic-trough collector for cleaner industrial process heat. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 89, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.B.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Optimization of concentrating solar thermal power plant based on parabolic trough collector. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 89, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, M.J.; Rovira, A.; Muñoz, M.; Martínez-Val, J.M. Performance analysis of an Integrated Solar Combined Cycle using Direct Steam Generation in parabolic trough collectors. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3228–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Soud, M.S.; Hrayshat, E.S. A 50 MW concentrating solar power plant for Jordan. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valan Arasu, A.; Sornakumar, T. Design, manufacture and testing of fiberglass reinforced parabola trough for parabolic trough solar collectors. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S. Use of parabolic trough solar energy collectors for sea-water desalination. Appl. Energy 1998, 60, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari Mosleh, H.; Mamouri, S.J.; Shafii, M.B.; Hakim Sima, A. A new desalination system using a combination of heat pipe, evacuated tube and parabolic through collector. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 99, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigoni, R.; Kötzsch, S.; Sorlini, S.; Egli, T. Solar water disinfection by a Parabolic Trough Concentrator (PTC): Flow-cytometric analysis of bacterial inactivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 67, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafie, M.; Ben Aissa, M.F.; Guizani, A. Energetic end exergetic performance of a parabolic trough collector receiver: An experimental study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, D.J.; Sprung, J.L.; Pacheco, J.E.; Prairie, M.R.; Reilly, H.E.; Milne, T.A.; Nimlos, M.R. Sandia National Laboratories’ work in solar detoxification of hazardous wastes. Sol. Energy Mater. 1991, 24, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Blanco, J.; Sichel, C.; Malato, S. Water disinfection by solar photocatalysis using compound parabolic collectors. Catal. Today 2005, 101, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOSOL Paineis Solares. Available online: http://www.aosol.pt/ (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- CADOX Project Website. Available online: https://www.psa.es/en/projects/cadox/ (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Sacco, O.; Vaiano, V.; Rizzo, L.; Sannino, D. Photocatalytic activity of a visible light active structured photocatalyst developed for municipal wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, J.; Andraka, C. Dish systems for CSP. Sol. Energy 2017, 152, 140–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, H.; Mokhiamar, O.; Elsamni, O. Mechanical design of a low cost parabolic solar dish concentrator. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarpani, R.R.Z.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle costs of advanced treatment techniques for wastewater reuse and resource recovery from sewage sludge. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettonte, M.; Miotello, A.; Brusa, R.S. Solar Concentrator, Method and Equipement for Its Achievement. 2007. Available online: http://www.sumobrain.com/patents/wipo/%20Solar-concentrator-method-equip ment-its/WO2008074485A1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Eccher, M.; Turrini, S.; Salemi, A.; Bettonte, M.; Miotello, A.; Brusa, R.S. Construction method and optical characterization of parabolic solar modules for concentration systems. Sol. Energy 2013, 94, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, M.; Filosa, N.; Bettonte, M.; Fendrich, M.; Girardini, M.; Battistini, T.; Miotello, A. Treatment of surfactant-rich industrial wastewaters with concentrated sunlight: Toward solar wastewater remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletta, S. A Solar Fresnel Collector Based on an Evacuated Flat Receiver. Energy Procedia 2016, 101, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, M.J.; Rubbia, C.; Abbas, R.; Martínez-Val, J.M. A comparative analysis of configurations of linear fresnel collectors for concentrating solar power. Energy 2014, 73, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boito, P.; Grena, R. Optimization of the geometry of Fresnel linear collectors. Sol. Energy 2016, 135, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, J.M.; Durán, A. Fresnel lens to concentrate solar energy for the photocatalytic decoloration and mineralization of orange II in aqueous solution. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Monteagudo, J.M. Solar photocatalytic degradation of reactive blue 4 using a Fresnel lens. Water Res. 2007, 41, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, J.M.; Durán, A.; Guerra, J.; García-Peña, F.; Coca, P. Solar TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of IGCC power station effluents using a Fresnel lens. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.K. A new photocatalytic reactor for destruction of toxic water pollutants by advanced oxidation process. Catal. Today 1998, 44, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.D.; Nakajima, A.; Watanabe, I.; Watanabe, T.; Hashimoto, K. TiO2-coated optical fiber bundles used as a photocatalytic filter for decomposition of gaseous organic compounds. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2000, 136, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danion, A.; Disdier, J.; Guillard, C.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Malic acid photocatalytic degradation using a TiO2-coated optical fiber reactor. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2007, 190, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peill, N.J.; Hoffmann, M. Solar Powered photocatalytic Fiber-Optic Cable Reactor for Waste Stream Remediation. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 1997, 119, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillert, R.; Cassano, A.E.; Goslich, R.; Bahnemann, D. Large scale studies in solar catalytic wastewater treatment. Catal. Today 1999, 54, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Perers, B.; Furbo, S.; Fan, J. Annual measured and simulated thermal performance analysis of a hybrid solar district heating plant with flat plate collectors and parabolic trough collectors in series. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sivakumar, M.; Yang, S.; Enever, K.; Ramezanianpour, M. Application of solar energy in water treatment processes: A review. Desalination 2018, 428, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutisna; Rokhmat, M.; Wibowo, E.; Khairurrijal; Abdullah, M. Prototype of a flat-panel photoreactor using TiO2 nanoparticles coated on transparent granules for the degradation of Methylene Blue under solar illumination. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2017, 27, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, O.M.; Bahnemann, D.; Cassano, A.E.; Dillert, R.; Goslich, R. Photocatalysis in water environments using artificial and solar light. Catal. Today 2000, 58, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minero, C.; Pelizzetti, E.; Malato, S.; Blanco, J. Large solar plant photocatalytic water decontamination: Degradation of pentachlorophenol. Chemosphere 1993, 26, 2103–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Puma, G. Dimensionless analysis of photocatalytic reactors using suspended solid photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 83, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, Y.K.; Imam, E.; Ramadan, A.R. TiO2 water-bell photoreactor for wastewater treatment. Sol. Energy 2018, 170, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaze, W.H.; Kang, J.W.; Chapin, D.H. The chemistry of water treatment processes involving ozone, hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet radiation. Ozone Sci. Eng. 1987, 9, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N. The contribution of non-thermal and advanced oxidation technologies towards dissipation of pesticide residues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Mur, E.; Sauleda, R.; Sànchez, L.; Peral, J.; Domènech, X.; Casado, J. Aniline mineralization by AOP’s: Anodic oxidation, photocatalysis, electro-Fenton and photoelectro-Fenton processes. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 1998, 16, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Ali, I.; Kim, J.O. Photodegradation of perfluorooctanoic acid by graphene oxide-deposited TiO2 nanotube arrays in aqueous phase. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 218, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehos, M.; Turchi, C.; Boegel, A.J.; Merrill, T.; Stanley, R. Pilot-Scale Study of the Solar Detoxification of VOC-Contaminated Groundwater; National Renewable Energy Laborary: Golden, CO, USA, 1992.

- Moraes, J.E.F.; Quina, F.H.; Nascimento, C.A.O.; Silva, D.N.; Chiavone-Filho, O. Treatment of Saline Wastewater Contaminated with Hydrocarbons by the Photo-Fenton Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, N.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kato, S.; Yang, Y. Effect of HCO3− concentration in groundwater on TiO2 photocatalytic water purification. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 242, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; An, H.; Zhai, J.; Li, Q.; Cui, H. Photocatalytic activity of Pt-TiO2 films supported on hydroxylated fly ash cenospheres under visible light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 324, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, N.; Sugasawa, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; Hirami, Y.; Koura, S. Effect of dissolved silica on photocatalytic water purification with a TiO2 ceramic catalyst. Water Res. 2019, 150, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterloh, F.E. Inorganic nanostructures for photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 2294–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.L.; Yates, J.T. Surface Science Studies of the Photoactivation of TiO2 New Photochemical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4428–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edla, R.; Patel, N.; Orlandi, M.; Bazzanella, N.; Bello, V.; Maurizio, C.; Mattei, G.; Mazzoldi, P.; Miotello, A. Highly photo-catalytically active hierarchical 3D porous/urchin nanostructured Co3O4 coating synthesized by Pulsed Laser Deposition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166–167, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbone, M.; Buccheri, M.A.; Cacciato, G.; Sanz Gonzàlez, R.; Rappazzo, G.; Boninelli, S.; Reitano, R.; Romano, L.; Privitera, V.; Grimaldi, M.G. {P}hotocatalytical and antibacterial activity of {T}i{O}2 nanoparticles obtained by laser ablation in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 165, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnemann, D. Photocatalytic water treatment: Solar energy applications. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, A.C.; Onyango, M.S.; Ochieng, A.; Momba, M.N.B. UV and solar photocatalytic disinfection of municipal wastewater: Inactivation, reactivation and regrowth of bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Soin, N.; Roy, S.S. Role of graphene/metal oxide composites as photocatalysts, adsorbents and disinfectants in water treatment: A review. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3823–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-García, N.; Maldonado, M.I.; Coronado, J.M.; Malato, S. Degradation study of 15 emerging contaminants at low concentration by immobilized TiO2 in a pilot plant. Catal. Today 2010, 151, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn-Chul, O. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Contaminants in Water; Iowa University: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gaya, U.I.; Abdullah, A.H. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over titanium dioxide: A review of fundamentals, progress and problems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2008, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Jaiswal, R.; Warang, T.; Scarduelli, G.; Dashora, A.; Ahuja, B.L.; Kothari, D.C.; Miotello, A. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic water pollutants using V-N-codoped TiO2 thin films. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 150–151, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Bharambe, J.; Patel, N.; Dashora, A.; Kothari, D.C.; Miotello, A. Copper and Nitrogen co-doped TiO2 photocatalyst with enhanced optical absorption and catalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 168–169, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Patel, N.; Dashora, A.; Fernandes, R.; Yadav, M.; Edla, R.; Varma, R.S.; Kothari, D.C.; Ahuja, B.L.; Miotello, A. Efficient Co-B-codoped TiO2 photocatalyst for degradation of organic water pollutant under visible light. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 183, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.S.; Thorat, N.; Fernandes, R.; Kothari, D.C.; Patel, N.; Miotello, A. Dependence of photocatalysis on charge carrier separation in Ag-doped and decorated TiO2nanocomposites. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 8428–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.Y.; Wen, T.; Fan, C.M.; Gao, G.Q.; Zhong, S.L.; Xu, A.W. Efficient adsorption/photodegradation of organic pollutants from aqueous systems using Cu2O nanocrystals as a novel integrated photocatalytic adsorbent. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14563–14570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.; Razmjou, A.; Wang, K.; Hapgood, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. TiO2 based photocatalytic membranes: A review. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 472, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Maldonado, M.I.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Oller, I.; Polo, I.; Sánchez-Moreno, R. Decontamination and disinfection of water by solar photocatalysis: The pilot plants of the Plataforma Solar de Almeria. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2016, 42, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Yin, L.; Dai, Y.; Bao, Y.; Crittenden, J.C. Design of visible light responsive photocatalysts for selective reduction of chlorinated organic compounds in water. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2016, 521, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edla, R.; Tonezzer, A.; Orlandi, M.; Patel, N.; Fernandes, R.; Bazzanella, N.; Date, K.; Kothari, D.C.; Miotello, A. 3D hierarchical nanostructures of iron oxides coatings prepared by pulsed laser deposition for photocatalytic water purification. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 219, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, J.; Hellín, P.; Martínez, C.M.; Flores, P.; Navarro, S. Semiconductor oxides-sensitized photodegradation of fenamiphos in leaching water under natural sunlight. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 115–116, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.B.; Nabi, G.; Rafique, M.; Khalid, N.R. Nanostructured-based WO3 photocatalysts: Recent development, activity enhancement, perspectives and applications for wastewater treatment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 2519–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.E.; Sierra, M.; Esparza, P. Solar photocatalysis at semi-pilot scale: Wastewater decontamination in a packed-bed photocatalytic reactor system with a visible-solar-light-driven photocatalyst. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, T.; Negishi, N.; Takeuchi, K.; Matsuzawa, S. Degradation of toluene and acetaldehyde with Pt-loaded TiO2 catalyst and parabolic trough concentrator. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, N.; Calín, M.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Garrido, I.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, S. Solar reclamation of wastewater effluent polluted with bisphenols, phthalates and parabens by photocatalytic treatment with TiO2/Na2S2O8 at pilot plant scale. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, E.M.; Fernández, G.; Klamerth, N.; Maldonado, M.I.; Álvarez, P.M.; Malato, S. Efficiency of different solar advanced oxidation processes on the oxidation of bisphenol A in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 95, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradov, N.Z. Solar detoxification of nitroglycerine-contaminated water using immobilized titania. Sol. Energy 1994, 52, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villén, L.; Manjón, F.; García-Fresnadillo, D.; Orellana, G. Solar water disinfection by photocatalytic singlet oxygen production in heterogeneous medium. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2006, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Verma, A.; Talwar, S. Detoxification of real pharmaceutical wastewater by integrating photocatalysis and photo-Fenton in fixed-mode. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 349, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatello, J.J.; Oliveros, E.; Mackay, A. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Organic Contaminant Destruction Based on the Fenton Reaction and Related Chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 36, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Vogelpohl, A. Degradation of Organic Pollutants by the Photo-Fenton-Process. Chem. Eng. Technol. 1998, 21, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruales-Lonfat, C.; Barona, J.F.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Bensimon, M.; Vélez-Colmenares, J.; Benítez, N.; Pulgarín, C. Iron oxides semiconductors are efficients for solar water disinfection: A comparison with photo-Fenton processes at neutral pH. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166–167, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, I.; Miralles-Cuevas, S.; Oller, I.; Malato, S.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Polo-López, M.I. Inactivation of E. coli and E. faecalis by solar photo-Fenton with EDDS complex at neutral pH in municipal wastewater effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edla, R.; Gupta, S.; Patel, N.; Bazzanella, N.; Fernandes, R.; Kothari, D.C.; Miotello, A. Enhanced H2 production from hydrolysis of sodium borohydride using Co3O4 nanoparticles assembled coatings prepared by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2016, 515, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, M.; Dalle Carbonare, N.; Caramori, S.; Bignozzi, C.A.; Berardi, S.; Mazzi, A.; El Koura, Z.; Bazzanella, N.; Patel, N.; Miotello, A. Porous versus Compact Nanosized Fe(III)-Based Water Oxidation Catalyst for Photoanodes Functionalization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 20003–20011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenato, M.; Ricardo, C.L.A.; Scardi, P.; Edla, R.; Miotello, A.; Orlandi, M.; Morrish, R. Effect of annealing and nanostructuring on pulsed laser deposited WS2 for HER catalysis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2016, 510, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, A.; Miotello, A. Simulation of phase explosion in the nanosecond laser ablation of aluminum. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 489, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizio, C.; Edla, R.; Michieli, N.; Orlandi, M.; Trapananti, A.; Mattei, G.; Miotello, A. Two-step growth mechanism of supported Co3O4-based sea-urchin like hierarchical nanostructures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Blanco, J.; Alarcón, D.C.; Maldonado, M.I.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Gernjak, W. Photocatalytic decontamination and disinfection of water with solar collectors. Catal. Today 2007, 122, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ibañez, P.; Malato, S.; Enea, O. Photoelectrochemical reactors for the solar decontamination of water. Catal. Today 1999, 54, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klare, M.; Scheen, J.; Vogelsang, K.; Jacobs, H.; Broekaert, J.A.C. Degradation of short-chain alkyl- and alkanolamines by TiO2- and Pt/TiO2-assisted photocatalysis. Chemosphere 2000, 41, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Aoshima, A.; Horikoshi, S.; Hidaka, H.; Zhao, J.; Serpone, N. Solar photocatalysis, photodegradation of a commercial detergent in aqueous TiO2 dispersions under sunlight irradiation. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minero, C.; Pelizzetti, E.; Malato, S.; Blanco, J. Large solar plant photocatalytic water decontamination: Effect of operational parameters. Sol. Energy 1996, 56, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandala, E.R.; Arancibia-Bulnes, C.A.; Orozco, S.L.; Estrada, C.A. Solar photoreactors comparison based on oxalic acid photocatalytic degradation. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Blanco, J.; Richter, C.; Curcó, D.; Giménez, J. Low-concentration CPC collectors for photocatalytic water detoxification: Comparison with a medium concentrating solar collector. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 35, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorjahan, M.; Reddy, M.P.; Kumari, V.D.; Lavédrine, B.; Boule, P.; Subrahmanyam, M. Photocatalytic degradation of H-acid over a novel TiO2 thin film fixed bed reactor and in aqueous suspensions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2003, 156, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitz, A.J.; Boyden, B.H.; Waite, T.D. Evaluation of two solar pilot scale fixed-bed photocatalytic reactors. Water Res. 2000, 34, 3927–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.C.; Chan, C.K.; Barford, J.P.; Porter, J.F. Solar photocatalytic thin film cascade reactor for treatment of benzoic acid containing wastewater. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Well, M.; Dillert, R.H.G.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Benz, V.W.; Mueller, M.A. A Novel Nonconcentrating Reactor for Solar Water Detoxification. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 1997, 119, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ao, Y.; Fu, D.; Lin, J.; Lin, Y.; Shen, X.; Yuan, C.; Yin, Z. Photocatalytic activity on TiO2-coated side-glowing optical fiber reactor under solar light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2008, 199, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kositzi, M.; Poulios, I.; Malato, S.; Caceres, J.; Campos, A. Solar photocatalytic treatment of synthetic municipal wastewater. Water Res. 2004, 38, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, V.; Baiocchi, C.; Bianco Prevot, A.; García-López, E.; Loddo, V.; Malato, S.; Marcí, G.; Palmisano, L.; Pazzi, M.; Pramauro, E. Azo-dyes photocatalytic degradation in aqueous suspension of TiO2 under solar irradiation. Chemosphere 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva Roselin, L.; Rajarajeswari, G.R.; Selvin, R.; Sadasivam, V.; Sivasankar, B.; Rengaraj, K. Sunlight/ZnO-Mediated photocatalytic degradation of reactive red 22 using thin film flat bed flow photoreactor. Sol. Energy 2002, 73, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, H.B.; Karkmaz, M.; Puzenat, E.; Guillard, C.; Herrmann, J.M. From the fundamentals of photocatalysis to its applications in environment protection and in solar purification of water in arid countries. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2005, 31, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Reina, A.; Miralles-Cuevas, S.; Rivas, G.; Sánchez Pérez, J.A. Comparison of different detoxification pilot plants for the treatment of industrial wastewater by solar photo-Fenton: Are raceway pond reactors a feasible option? Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 648, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteagudo, J.M.; Durán, A.; San Martín, I.; Aguirre, M. Effect of continuous addition of H2O2 and air injection on ferrioxalate-assisted solar photo-Fenton degradation of Orange II. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 89, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montaño, J.; Pérez-Estrada, L.; Oller, I.; Maldonado, M.I.; Torrades, F.; Peral, J. Pilot plant scale reactive dyes degradation by solar photo-Fenton and biological processes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2008, 195, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberidou, C.; Kitsiou, V.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Antoniadis, A.; Ntonou, E.; Zalidis, G.C.; Poulios, I. Evaluation of an alternative method for wastewater treatment containing pesticides using solar photocatalytic oxidation and constructed wetlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 195, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, V.; García-López, E.; Loddo, V.; Malato-Rodríguez, S.; Maldonado, I.; Marcì, G.; Molinari, R.; Palmisano, L. Degradation of lincomycin in aqueous medium: Coupling of solar photocatalysis and membrane separation. Sol. Energy 2005, 79, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, O.A.; Kehoe, S.C.; McGuigan, K.G.; Duffy, E.F.; Al Touati, F.; Gernjak, W.; Oller Alberola, I.; Malato Rodríguez, S.; Gill, L.W. Solar disinfection of contaminated water: A comparison of three small-scale reactors. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenhammer, H.; Bahnemann, D.; Bousselmi, L.; Geissen, S.U.; Ghrabi, A.; Saleh, F.; Si-Salah, A.; Siemon, U.; Vogelpohl, A. Detoxification and recycling of wastewater by solar-catalytic treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 35, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-López, M.I.; García-Fernández, I.; Velegraki, T.; Katsoni, A.; Oller, I.; Mantzavinos, D.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P. Mild solar photo-Fenton: An effective tool for the removal of Fusarium from simulated municipal effluents. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 111–112, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahim-Granados, S.; Sánchez Pérez, J.A.; Polo-Lopez, M.I. Effective solar processes in fresh-cut wastewater disinfection: Inactivation of pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enteritidis. Catal. Today 2018, 313, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguas, Y.; Hincapie, M.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Polo-López, M.I. Solar photocatalytic disinfection of agricultural pathogenic fungi (Curvularia sp.) in real urban wastewater. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 607–608, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzmanova, Y.; Ustundas, M.; Stoller, M.; Chianese, A. Photocatalytic treatment of olive mill wastewater by n-doped titanium dioxide nanoparticles under visible light. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2013, 32, 2233–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Monteagudo, J.M.; Gil, J.; Expósito, A.J.; San Martín, I. Solar-photo-Fenton treatment of wastewater from the beverage industry: Intensification with ferrioxalate. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 270, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienza, M.; Mahdi Ahmed, M.; Escande, A.; Plantard, G.; Scrano, L.; Chiron, S.; Bufo, S.A.; Goetz, V. Use of solar advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: Follow-up on degradation products, acute toxicity, genotoxicity and estrogenicity. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onotri, L.; Race, M.; Clarizia, L.; Guida, M.; Alfè, M.; Andreozzi, R.; Marotta, R. Solar photocatalytic processes for treatment of soil washing wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 318, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]