The Accuracy of Predicted Acoustical Parameters in Ancient Open-Air Theatres: A Case Study in Syracusae

Abstract

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Section 2 (Case Study) includes a brief description of the state of conservation of the theatre chosen for this research.

- Section 3 (In Situ Measurements) includes a description of the acoustical measurement campaign carried out in the investigated theatre.

- Section 4 (Uncertainty Expression of the Acoustic Prediction Models) comprises the assessment of the uncertainty contribution related to the absorption (αw) and scattering (s) input data assigned to the materials, predicted with Odeon (v. 13.02) (Odeon A/S, Lyngby, Denmark), and with CATT-Acoustic (v. 9) (CATT, Gothenburg, Sweden) software.

- Section 5 (Discussion) is focused on analysing the differences between measured (in situ) and predicted (through software) acoustic parameters, and it includes a discussion on the overall limitations of the study.

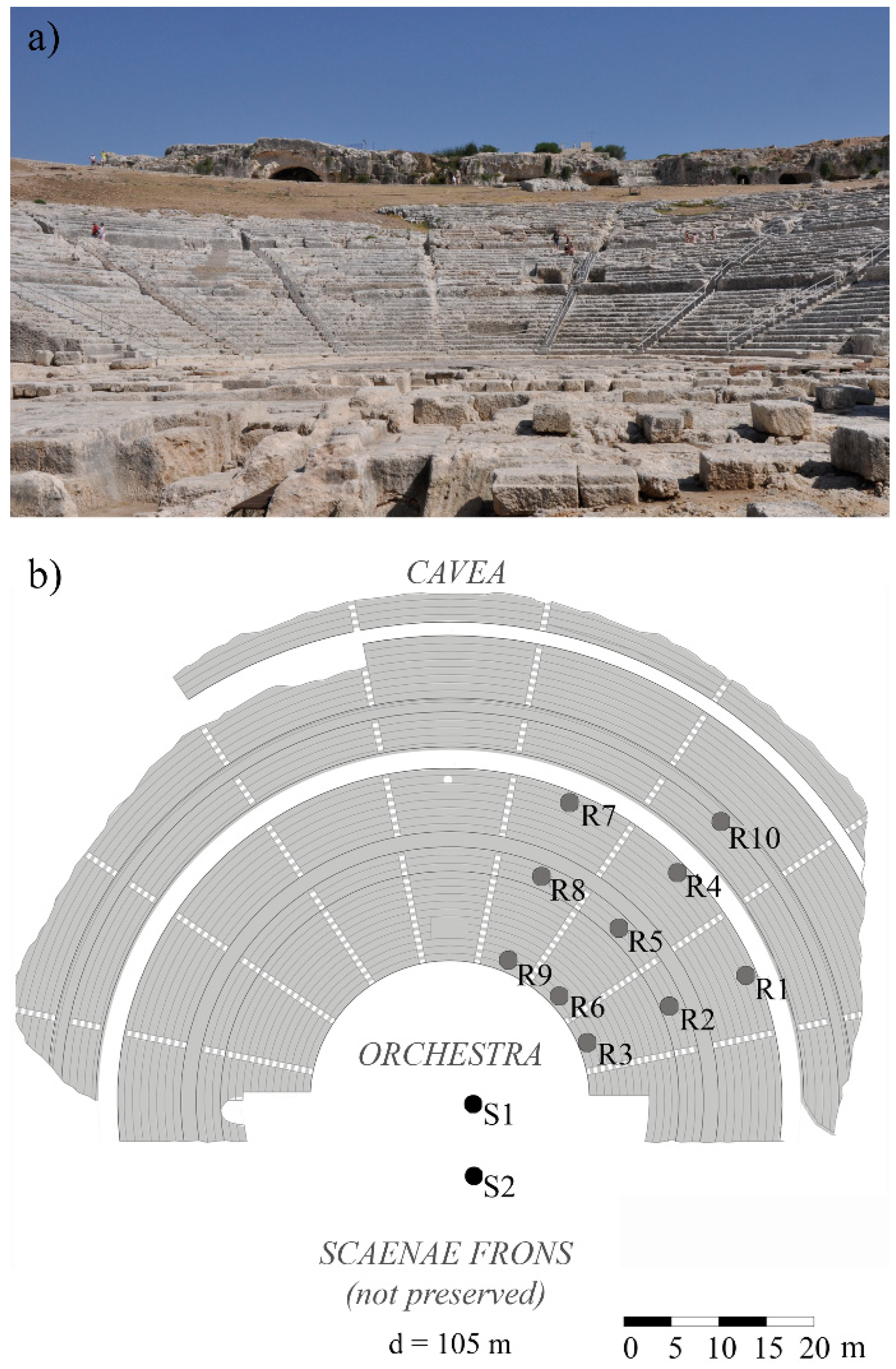

2. Case Study

3. In Situ Measurement Methods

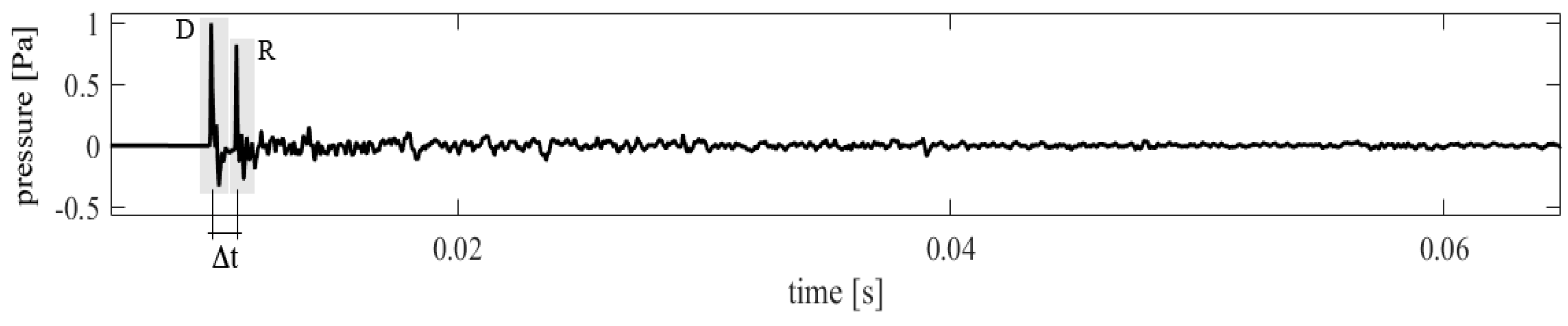

- Reverberation time, RT, (s): duration required for the space-averaged sound energy density in an enclosure to decrease by 60 dB after the source emission has stopped. The integrated impulse response method was applied to obtain the RT from the IR [2]. RT can be evaluated on a smaller dynamic range than 60 dB and extrapolated to a decay time of 60 dB. It is then labelled accordingly. The RT in SR was derived from decay values of 5 dB to 25 dB below the initial level, and it was therefore labelled T20.

- Clarity, C80, (dB): the balance between early- and late-arriving energy. This was calculated for an 80 ms early time limit, as the results were intended to relate to music conditions, using equation:where p(t) is the instantaneous sound pressure of the impulse response measured at the measurement point.

- Sound Strength, G, (dB): the logarithmic ratio of the measured sound energy (i.e., the squared and integrated sound pressure) to the sound energy that would arise in a free field at a distance of 10 m from a calibrated omnidirectional sound source, as expressed in the following equations:in whichandwhere:

- p(t) is the instantaneous sound pressure of the impulse response measured at the measurement point;

- p10(t) is the instantaneous sound pressure of the impulse response measured at a distance of 10 m in a free field;

- LpE (dB) is the sound exposure level of p(t);

- LpE,10 (dB) is the sound exposure level of p10(t);

- p0 is the reference sound pressure of 20 μPa;

- T0 is the reference time interval of 1 s.

Measurements Results

4. Uncertainty of the Geometrical Acoustic Prediction Models

4.1. General Procedure for the Implementation of the Models

- Geometrical model: MATLAB software, version R2015b, was used to create a parametric open-air theatre script. Two 3D cavea model script outputs were created, one suitable for Odeon (dxf file) and the other for CATT-Acoustic (.geo file). In order to reduce the simulation time, the theatre geometry was simplified and designed as symmetric. A few geometrical simplifications have been performed in both Odeon and CATT-A models. The number of surfaces was 1357 in CATT-Acoustic and 1362 in Odeon. As recommended previously [14], the steps were modelled. The higher number of surfaces in Odeon corresponds to an additional boundary box with totally absorbing walls and top which is required in Odeon to simulate open-air conditions [22]. CATT-A algorithms are implemented in order to detect lost rays, i.e., rays that escape from the geometrical model. In open cases, such as an open-air ancient theatre, rays disappear whenever they do not hit any surface during the calculation time. This principle is similar to the one used in Odeon, where the escaping rays disappear since they are totally absorbed by the boundary box. The circular geometry was modelled with 20 segments, as recommended by Charmouziadou [40], who showed that a number between 12 and 24 segments is optimal with respect to the influence on the objective acoustic parameters.

- Source-receivers: The source-receiver path was defined as in the measurement set-up, considering the theatre as unoccupied. For an easier comparison, only the source in position S1 was considered, as shown in Figure 3a.

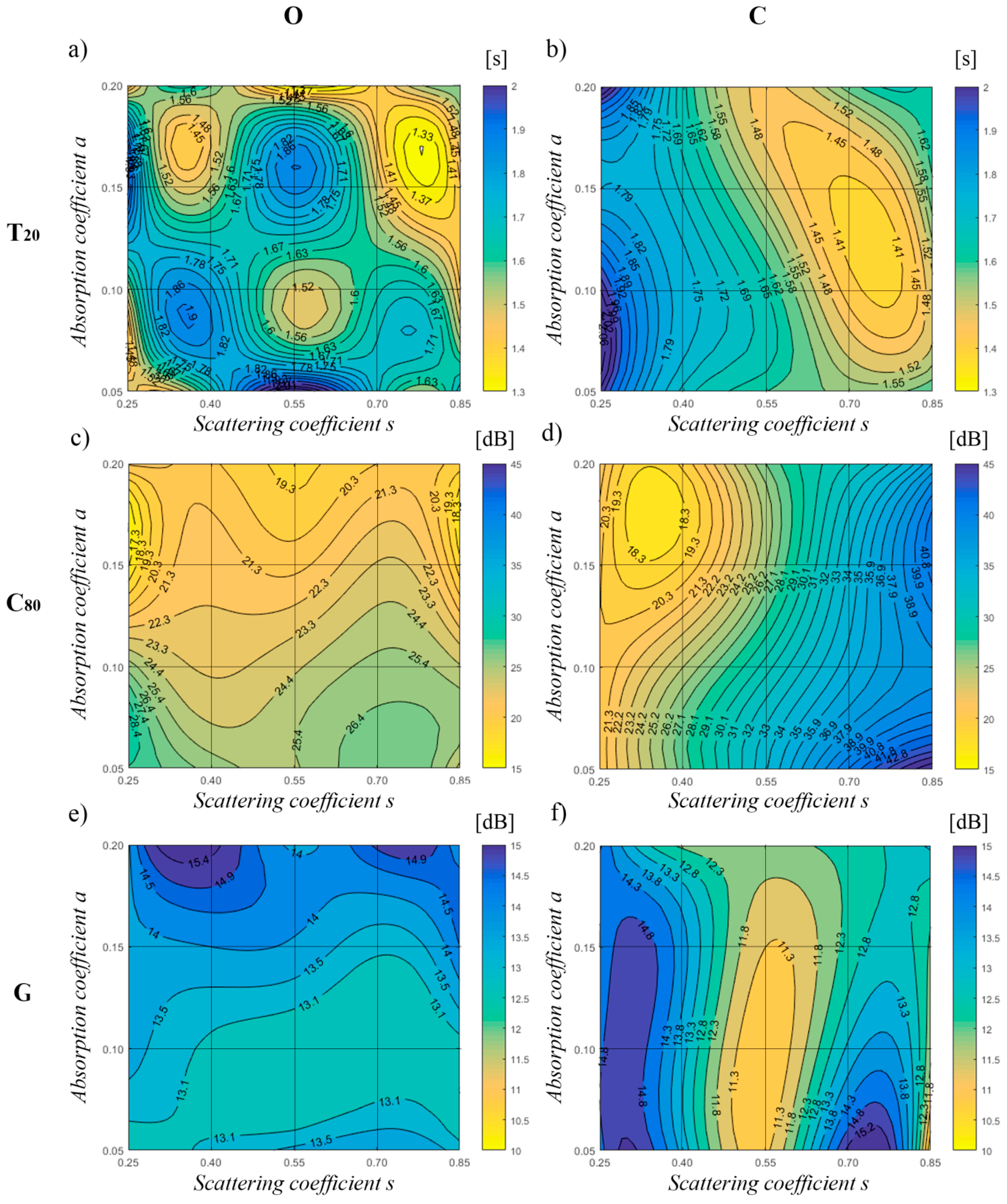

- Surface material properties: The main surface considered in the model was the cavea, the stone and steps of which are not well-conserved. In both types of software, 20 material alternatives were assigned to the cavea stone, that is, from the most reflective one, with αw = 0.05 and s = 0.25, to the most porous one, with αw = 0.2 and s = 0.85, and all the intermediate combinations of αw were tested in steps of 0.05, while s was tested in steps of 0.15, as explained in Figure 4b [14]. Other elements were then added: the remains of the ancient entrances to the orchestra area (aditi maximi), which was considered as an aperture (αw = 0.9; s = 0), and the floor, which includes the ruins of the scaenae frons (αw = 0.8; s = 0.8) and the better conserved orchestra area (αw = 0.1; s = 0.2). Odeon and CATT-Acoustic software allow for frequency dependent absorption coefficients. The same absorption coefficients have been used for both software. The Odeon software allows giving as input value for the scattering coefficient the value as an average between 500 and 1000 Hz, and considers a frequency dependent scattering by using default interpolation curves as shown in the Manual. These curves have been used in CATT-Acoustic, i.e., a frequency dependent scattering coefficient, by inserting each value for each octave-band. The values given in Figure 4b refer to the mean values at 500 and 1000 Hz.

- General settings: The following settings were considered for all the simulations: a 100 dB source sound power level, 1500 ms as the impulse response length, and 4 million rays. The Transition Order (TO) in Odeon was limited to 1, which better resembles the impulse response characteristics in the real condition with only one specular reflection from the stage floor. The third calculation algorithm in CATT-Acoustic, described above, was chosen as it is the most suitable for the simulation of open-air spaces. Scattering and diffraction settings were defined as in Table 2 in order to allow a more coherent comparison between the two software. The diffraction phenomenon occurs when a sound wave hits edges, i.e., intersections between surfaces, or when the surface dimensions are limited. Both these events are taken into account by the software Odeon and CATT-A when the Reflection-Based Scattering and Diffuse reflection method are enabled. In Odeon, the Lambert and the Oblique Lambert functions for scattering were disabled, as suggested in a previous paper [39]. The uniform scattering distribution was considered more suitable for the cavea which is made of steps that can be reassembled as periodic triangular section [39,40,41], as shown in Figure 3a. In CATT-Acoustic, the diffraction after 1st order option was deactivated, even though it is usually suggested for ancient theatres [42], in order to take into account the current large amount of damage to the cavea steps in SR. In this way, it was possible to avoid the typical “chirp” echo due to diffraction phenomenon which has been attested to come from the regular stone steps in ancient theatres in empty conditions [43]. This phenomenon was not encountered during in situ measurements or recordings in SR. However, the first order diffraction has been taken into account since it occurs in coherence to the scattering phenomena. Moreover, based on the literature [44], it was found that higher orders and combinations of edge diffraction components were not usually as significant as first-order diffraction components when the receiver was visible to the source. The environmental data considered in both of the prediction tools were those obtained during the in situ measurements (t = 33 °C, RH = 65%).

- Data analysis: the analysis algorithm has been taken into account. Odeon conducts an energy based analysis, while the CATT-Acoustic software conducts both energy and pressure-based analyses. The variation of different types of analysis algorithms can lead to different results, as pointed out in Katz [45]. Thus, in order to avoid further uncertainty in the results, the simulated IRs have been exported and analysed by means of Aurora, version 4.4, in the same way as the measurements.

4.2. Run-to-Run Variation

4.3. Number of Rays

4.4. Absorption and Scattering Coefficients

5. Discussion

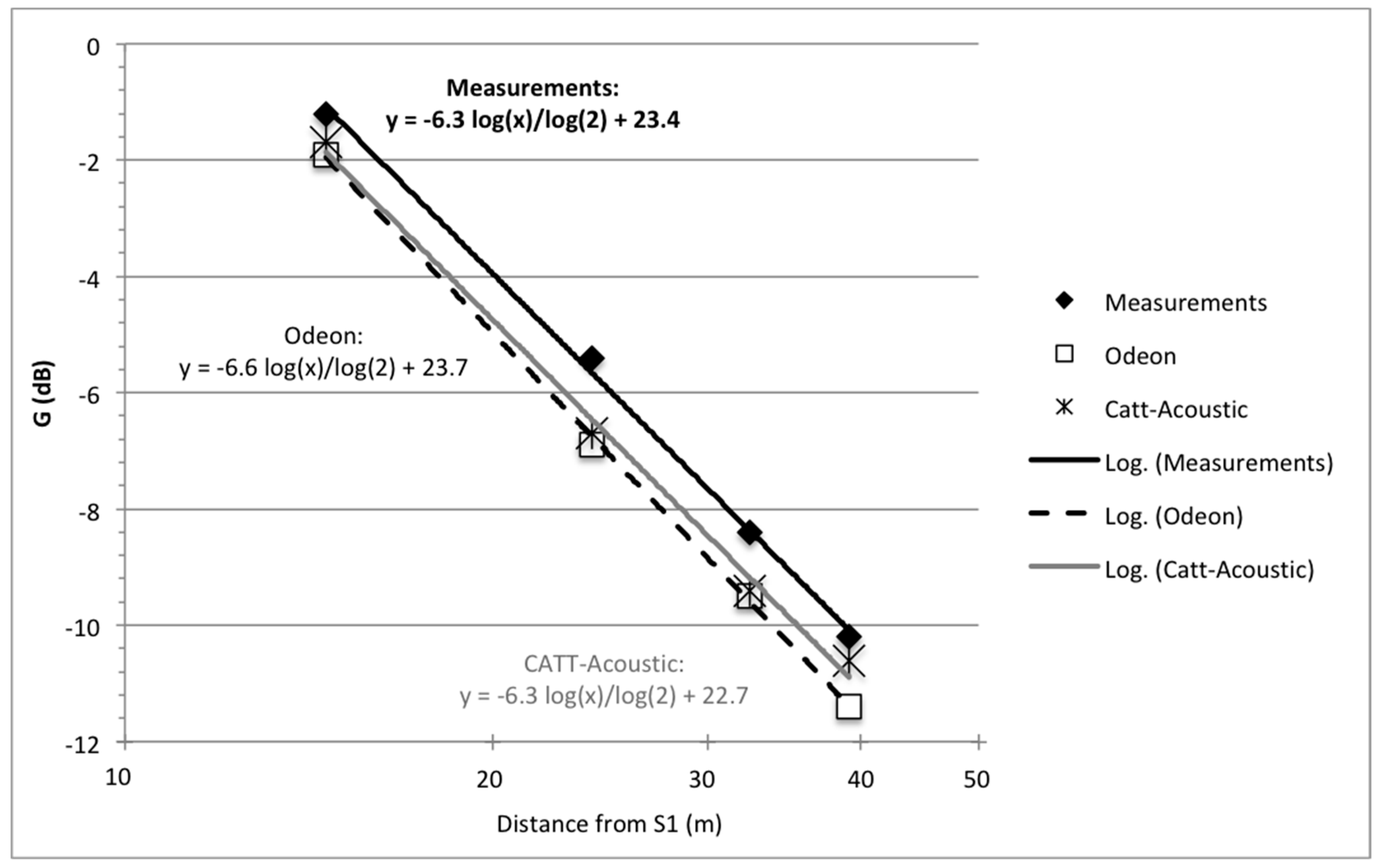

5.1. Comparison of the Measured and Simulated Results

5.2. Limitations of the Study

6. Concluding Remarks

- The uncertainty, due to the input variability of αw and s, is lower than the JND for T20 and C80, when the Odeon software is considered, and for G when both types of software are considered;

- Apart from T20, Odeon software is more sensitive to variation of sound absorption than of sound scattering, while the opposite occurs for CATT-Acoustics;

- Comparable behaviour of the simulated values of G has been shown for both types of software; G has been found to be the most suitable parameter for the calibration of the open-air theatre model;

- A good agreement with the measured values has been found, at the limit of the JNDs, in the calibrated model for all the parameters, in spite of the limitation of the GA software that has emerged in this case study, for both types of software.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scarre, C.; Lawson, G. Archeoacoustics; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 3382-1:2009. Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters—Part 1: Performance Spaces; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rindel, J.H. ERATO; Final Report, INCO-MED Project ICA3-CT-2002-10031; ERATO Project: Lyngby, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Farnetani, A.; Prodi, N.; Pompoli, R. On the acoustic of ancient Greek and Roman Theatres. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 124, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chourmouziadou, K.; Kang, J. Acoustic evolution of ancient Greek and Roman theatres. Appl. Acoust. 2008, 69, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J. The Conventional RT is Not Applicable for Testing the Acoustical Quality of Unroofed Theatres. Build. Acoust. 2013, 20, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannace, G.; Trematerra, A.; Masullo, M. The large theatre of Pompeii: Acoustic evolution. Build. Acoust. 2013, 20, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannace, G.; Trematerra, A. The rediscovery of Benevento Roman theatre acoustics. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guski, M. Influences of External Error Sources on Measurements of Room Acoustic Parameters. Ph.D. Thesis, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akama, T.; Suzuki, H.; Omoto, A. Distribution of selected monaural acoustical parameters in concert halls. Appl. Acoust. 2010, 71, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelorson, X.; Vian, J.P.; Polack, J.D. On the variability of room acoustical parameters: Reproducibility and statistical validity. Appl. Acoust. 1992, 37, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, P.; Zastawnik, M.; Wiciak, J.; Kamisinski, T. The influence of the measurement chain on the impulse response of a reverberation room and its application listening tests. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2011, 119, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorländer, M. Computer simulations in room acoustics: Concepts and uncertainties. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisa, M.; Rindel, J.H.; Christensen, C.L. Predicting the acoustics of open-air theatres: The importance of calculation methods and geometrical details. In Proceedings of the Baltic-Nordic Acoustics Meeting, Mariehamn, Aland, 8–10 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gade, A.C.; Lynge, C.; Lisa, M.; Rindel, J.H. Matching simulations with measured acoustic data from Roman Theatres using the Odeon program. In Proceedings of the Forum Acusticum, Budapest, Hungary, 29 August–2 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vorländer, M. International round robin on room acoustical computer simulations. In Proceedings of the 15th International Congress on Acoustics, Trondheim, Norway, 26–30 June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bork, I. A comparison of room simulation software—the 2nd Round Robin on Room Acoustical Computer Simulations. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2000, 86, 943–946. [Google Scholar]

- Bork, I. Report on the 3rd Round Robin on Room Acoustical Computer Simulation—Part II: Calculations. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2005, 91, 753–763. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 354:2003. Acoustics—Measurement of Sound Absorption in a Reverberation Room; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 17497-1:2004. Acoustics—Sound-Scattering Properties of Surface—Part 1: Measurement of the Random-Incidence Scattering Coefficient in a Reverberation Room; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farnetani, A.; Prodi, N.; Roberto, P. Measurements of the sound scattering of the steps of the cavea in ancient open air theatres. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Room Acoustics, Seville, Spain, 10–12 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.L.; Koutsouris, G. Odeon Room Acoustics Software. Version 13. Full User’s Manual, Odeon A/S, Lyngby, Denmark. 2015. Available online: https://www.odeon.dk/ (accessed on 10 January 2015).

- Dalenback, B.I.L. CATT-A v9.0, User’s Manual, CATT-Acoustic v9, CATT, Sweden. 2011. Available online: https://www.catt.se/ (accessed on 10 January 2015).

- Prodi, N.; Farnetani, A.; Fausti, P.; Pompoli, R. On the use of ancient open-air theatres for modern unamplified performances: A scale model approach. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2013, 99, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, E.; Astolfi, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Pelegrín Garcia, D.; Puglisi, G.E.; Shtrepi, L.; Rychtarikova, M. The modern use of ancient theatres related to acoustic and lighting requirements: Stage design guidelines for the Greek theatre of Syracuse. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, M.; La Pica, A.; Rodonò, G.; Vinci, V. Acoustic characterization of the ancient theatre at Syracuse. In Proceedings of the Acoustics Conference, Paris, France, 29 June–4 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A. Personal Communications, Syracuse Measurements Data (Realised in 2003). 2013. Available online: http://www.angelofarina.it/Siracusa/ (accessed on 30 September 2016).

- Bo, E.; Bergoglio, M.; Astolfi, A.; Pellegrino, A. Between the Archaeological Site and the Contemporary Stage: An Example of Acoustic and Lighting Retrofit with Multifunctional Purpose in the Ancient Theatre of Syracuse. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindel, J.H. Echo problems in ancient theatres and a comment to the sounding vessels described by Vitruvius. In Proceedings of the Acoustics of Ancient Theatres Conference, Patras, Greece, 18–21 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- San Martin, R.; Arana, M.; Machin, J.; Arregui, A. Impulse source versus dodecahedral loudspeaker for measuring parameters derived from the impulse response in room acoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelo Farina’s personal Home Page. Available online: http://pcfarina.eng.unipr.it/Aurora_XP/index.htm (accessed on 4 July 2016).

- Martellotta, F. The just noticeable difference of center time and clarity index in large reverberant spaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, M.G.; Buck, A.T.; Peng, Z.; Wang, L.M. Quantifying the just noticeable difference of reverberation time with band-limited noise centered around 1000 Hz using a transformed up-down adaptive method. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Room Acoustics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–11 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.J.; Davies, W.J.; Lam, Y.W. The sensitivity of listeners to early sound field changes in auditoria. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1993, 79, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J.S.; Reich, R.; Norcross, S.G. A just noticeable difference in C50 for speech. Appl. Acoust. 1999, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, D.; Pohl, A. Modeling (non-)uniform scattering distributions in geometrical acoustics. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Acoustics, ICA 2013, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–7 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, U.M. Eine Schallteilchen-Computer-Simulation zur Berechnung der für die Hörsamkeit in Konzertsälen maßgebenden Parameter. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1985, 59, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rindel, J.H. A new scattering method that combines roughness and diffraction effects. In Proceedings of the Forum Acusticum, Budapest, Hungary, 29 August–2 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shtrepi, L.; Astolfi, A.; Puglisi, G.E.; Masoero, M.C. Effects of the Distance from a Diffusive Surface on the Objective and Perceptual Evaluation of the Sound Field in a Small Simulated Variable-Acoustics Hall. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmouziadou, K. Ancient and Contemporary Use of the Open-Air Theatres: Evolution and Acoustic Effects of Scenery Design. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Architecture, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.J.; D’Antonio, P. Acoustic Absorbers and Diffusers: Theory, Design and Application; Spon: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–476. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, P.; Charalampous, P. The significance of sound diffraction effects in predicting acoustics in ancient theatres. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2013, 99, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, N.F.; Degrick, J.; Briers, R.; Leroy, O. A theoretical study of special acoustic effects caused by the staircase of the El Castillo pyramid at the Maya ruins of Chichen-Itza in Mexico. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 116, 3328–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, R.R.; Svensson, U.P.; Kleiner, M. Computation of edge diffraction for more accurate room acoustics auralization. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 109, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, B.F.G. International round robin on room acoustical response analysis software. Acoust. Res. Lett. 2004, 5, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC Guide 43-1. Proficiency Testing by Interlaboratory Comparisons. Part 1: Development and Operation of Proficiency Testing Schemes; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, B.N.J.; Katz, B.F.G. Creation and calibration method of acoustical models for historic virtual reality auralizations. Virtual Real. 2015, 19, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorländer, M. Auralization: Fundamentals of Acoustics, Modeling, Simulation, Algorithms and Acoustic Virtual Reality; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shtrepi, L.; Astolfi, A.; Pelzer, S.; Vitale, R.; Rychtarikova, M. Objective and perceptual assessment of the scattered sound field in a simulated concert hall. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2015, 138, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JCGM 100:2008. Expression of Measurement Data—Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement; Bureau International des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, G.; Germak, A.; Genta, G. Measurements for Decision Making. Measurements and Basic Statistics; Esculapio: Bologna, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, W. A Comparative Study of Different Distances for Similarity Estimation. In Intelligent Computing and Information Science; Chen, R., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 134. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, Y.W. A comparison of three diffuse reflection modeling methods used in room acoustics computer models. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996, 100, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M. Interpretation of Early Decay Time in concert auditoria. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1995, 81, 320–331. [Google Scholar]

- Sumarac-Pavlovic, D.; Mijic, M.; Kurtovic, H. A simple impulse sound source for measurements in room acoustics. Appl. Acoust. 2008, 69, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acoustical Parameters | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row | Receiver | No. of Repetitions | Distance from Source (m) | T20 (s) (St. Dev.) | C80 (dB) (St. Dev.) | G (dB) (St. Dev.) | INR (dB) | ||||||

| S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | ||

| First row | R3 | 2 | 2 | 13.8 | 18.7 | 0.58 (0.09) | 0.80 (0.02) | 20.8 (3.0) | 13.3 (0.6) | −0.3 (0.3) | −3.0 (0.1) | 58 | 60 |

| R6 | 3 | 2 | 14.6 | 21.2 | 0.70 (0.04) | 0.84 (0.01) | 16.9 (2.3) | 15.2 (0.6) | −0.9 (0.4) | −5.2 (0.1) | 51 | 57 | |

| R9 | 2 | 2 | 15.5 | 23.0 | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.14) | 22.1 (0.5) | 16.9 (0.8) | −2.4 (0.1) | −9.7 (0.0) | 52 | 55 | |

| Sp. mean | 14.6 | 20.9 | 0.53 (0.20) | 0.75 (0.13) | 19.9 (2.7) | 15.1 (1.8) | −1.2 (1.1) | −6.0 (3.4) | - | - | |||

| Second row | R2 | 2 | 2 | 23.3 | 27.5 | 0.81 (0.07) | 0.83 (0.01) | 16.5 (0.7) | 11.0 (0.8) | −4.8 (0.2) | −6.4 (0.1) | 57 | 55 |

| R5 | 2 | 2 | 24.0 | 30.2 | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.85 (0.03) | 19.2 (3.8) | 13.3 (0.2) | −5.4 (1.0) | −7.2 (0.1) | 50 | 52 | |

| R8 | 2 | 2 | 24.9 | 32.3 | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.91 (0.11) | 15.9 (2.8) | 13.0 (1.6) | −6.0 (0.0) | −8.5 (0.4) | 50 | 54 | |

| Spatial mean | 24.1 | 30.0 | 0.73 (0.08) | 0.87 (0.04) | 17.2 (1.8) | 12.4 (1.3) | −5.4 (0.6) | −7.4 (1.1) | - | - | |||

| Third row | R1 | 2 | 2 | 31.7 | 35.6 | 0.98 (0.05) | 0.96 (0.01) | 15.4 (2.0) | 11.2 (0.1) | −7.8 (0.5) | −8.3 (0.1) | 52 | 53 |

| R4 | 3 | 2 | 32.4 | 38.4 | 0.94 (0.15) | 0.98 (0.03) | 16.9 (1.8) | 12.7 (1.1) | −8.0 (0.7) | −9.6 (0.3) | 51 | 51 | |

| R7 | 2 | 2 | 33.3 | 40.6 | 1.04 (0.09) | 1.05 (0.01) | 15.7 (0.2) | 13.9 (0.0) | −9.3 (0.2) | −10.5 (0.0) | 51 | 50 | |

| Spatial mean | 32.5 | 38.2 | 0.99 (0.05) | 1.00 (0.05) | 16.0 (0.8) | 12.6 (1.3) | −8.4 (0.8) | −9.4 (1.1) | - | - | |||

| R10 | 2 | 2 | 39.2 | 45.6 | 1.31 (0.03) | 1.91 (0.05) | 14.3 (0.2) | 12.3 (0.1) | −10.2 (0.3) | −11.2 (0.4) | 52 | 49 | |

| Phenomenon | Model | Odeon | CATT-Acoustic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scattering | Lambert | Disabled | Late part of the IR (not manageable by the user) |

| Oblique Lambert | Disabled | Not managed by the software | |

| Uniform | Enabled, for early and late part of the IR | Early part of the IR (not manageable by the user) | |

| Edge + surface diffraction | Enabled (i.e., Reflection-Based Scattering) | Enabled (in CATT-A, i.e., Diffuse reflection) | |

| Diffraction after 1st order | Not managed by the software | Disabled (in TUCT) |

| Acoustical Parameter | JND | UO | UC |

|---|---|---|---|

| T20 (s) | 5% ≈ 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| C80 (dB) | 1 | 0.50 | 1.20 |

| G (dB) | 1 | 0.01 | 0.30 |

| Acoustical Parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row | Receiver | T20 (s) | C80 (dB) | G (dB) | ||||||

| Measured | Pred. (Odeon) | Pred. (Catt) | Measured | Pred. (Odeon) | Pred. (Catt) | Measured | Pred. (Odeon) | Pred. (Catt) | ||

| First row | R3 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 20.8 | 17.0 | 15.1 | −0.3 | −1.7 | −1.0 |

| R6 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 16.9 | 17.0 | 15.2 | −0.9 | −2.3 | −2.6 | |

| R9 | 0.31 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 22.1 | 15.4 | 15.3 | −2.4 | −1.8 | −1.4 | |

| spatial mean | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 19.9 | 16.5 | 15.2 | −1.2 | −1.9 | −1.7 | |

| Second row | R2 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 16.5 | 14.6 | 14.5 | −4.8 | −6.7 | −6.4 |

| R5 | 0.66 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 19.2 | 15.3 | 14.6 | −5.4 | −7.1 | −6.7 | |

| R8 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 15.9 | 14.5 | 15.4 | −6.0 | −7.0 | −7.0 | |

| spatial mean | 0.73 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 17.2 | 14.8 | 14.8 | −5.4 | −6.9 | −6.7 | |

| Third row | R1 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 15.4 | 14.0 | 13.0 | −7.8 | −9.0 | −9.0 |

| R4 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 16.9 | 13.9 | 12.5 | −8.0 | −9.8 | −9.6 | |

| R7 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 15.7 | 13.8 | 14.2 | −9.3 | −9.8 | −9.7 | |

| spatial mean | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 16.0 | 13.9 | 13.2 | −8.4 | −9.5 | −9.4 | |

| R10 | 1.31 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 15.2 | −10.2 | −11.4 | −10.6 | |

| ISO 3382-1 Section | Recommendation | Implemented | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4. Measurement conditions | Temperature and Relative Humidity: these quantities should be measured with an accuracy of ±1 °C and 5%, respectively. | X | |

| Equipment: omnidirectional sources and receivers. Maximum deviations of directivity for an omnidirectional source are indicated. | X | The deviation of directivity of the used sound source respected the maximum values indicated by the standards [30,54,55]. | |

| Number of source positions: minimum 2, located where the natural sound source would take position. Height of sources: 1.5 m. | X | ||

| Number of microphone positions: Microphone positions should be at positions representative of positions where listeners would normally be located. For reverberation time measurements, it is important that the measurement positions sample the entire space; for the room acoustic parameters, they should also be selected to provide information on possible systematic variations with position in the room. Height of the receivers: 1.2 m. | X | ||

| 5. Measurement procedures | Integrated Impulse Response method: any source is allowed provided that its spectrum is broad enough to cover from 125 Hz to 4 kHz. The peak sound pressure level has to ensure a decay curve starting at least 35 dB above the BNL. | X | In some receiving positions, the 125 Hz frequency band did not guarantee the required 35 dB over the BNL, with the firecrackers. |

| Time averaging: it is necessary to verify that the averaging process does not alter the measured impulse responses. | |||

| 6. Decay curves | Regression analysis: a least-squares fit line shall be computed for the decay curve. If the curves are wavy or bent, this may indicate a mixture of modes with different reverberation times and thus the result may be unreliable. | The open-air condition is characterised by a cliff-decay curve [54] linked to a few strong reflections, but this case is not considered by the standard. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bo, E.; Shtrepi, L.; Pelegrín Garcia, D.; Barbato, G.; Aletta, F.; Astolfi, A. The Accuracy of Predicted Acoustical Parameters in Ancient Open-Air Theatres: A Case Study in Syracusae. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8081393

Bo E, Shtrepi L, Pelegrín Garcia D, Barbato G, Aletta F, Astolfi A. The Accuracy of Predicted Acoustical Parameters in Ancient Open-Air Theatres: A Case Study in Syracusae. Applied Sciences. 2018; 8(8):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8081393

Chicago/Turabian StyleBo, Elena, Louena Shtrepi, David Pelegrín Garcia, Giulio Barbato, Francesco Aletta, and Arianna Astolfi. 2018. "The Accuracy of Predicted Acoustical Parameters in Ancient Open-Air Theatres: A Case Study in Syracusae" Applied Sciences 8, no. 8: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8081393

APA StyleBo, E., Shtrepi, L., Pelegrín Garcia, D., Barbato, G., Aletta, F., & Astolfi, A. (2018). The Accuracy of Predicted Acoustical Parameters in Ancient Open-Air Theatres: A Case Study in Syracusae. Applied Sciences, 8(8), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8081393