Diode Laser Welding/Brazing of Aluminum Alloy to Steel Using a Nickel Coating

Abstract

:1. Introduction

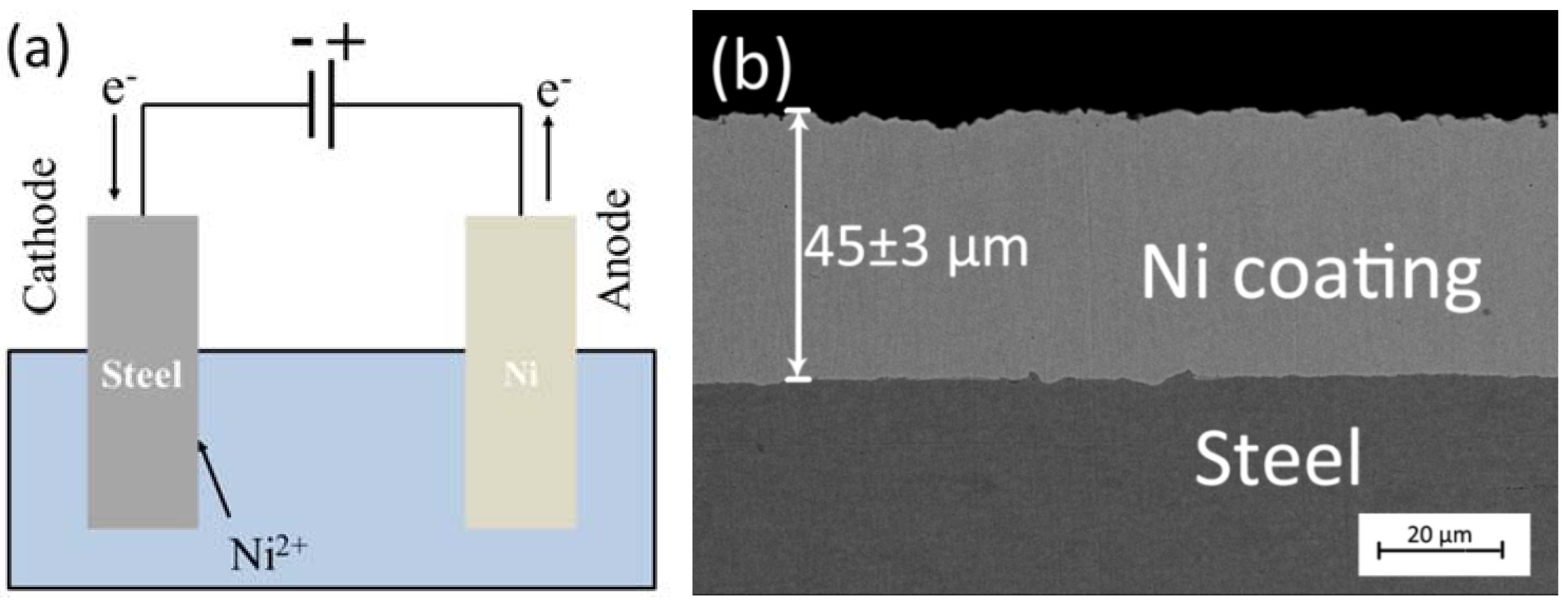

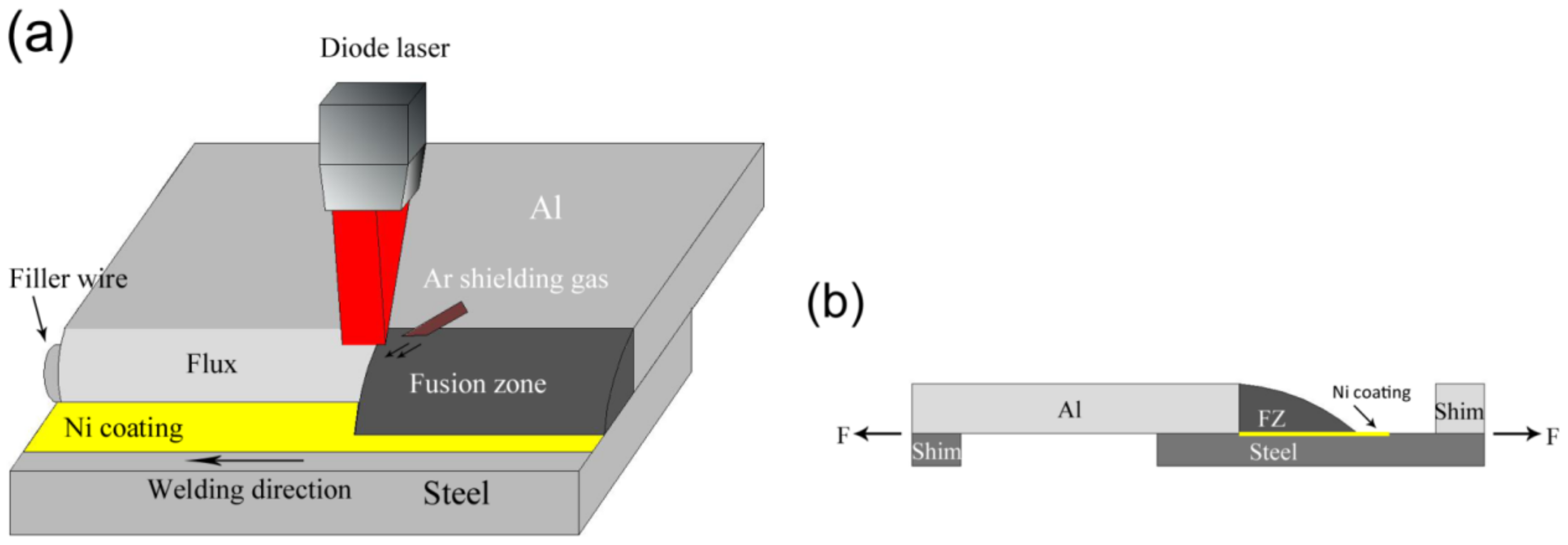

2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results

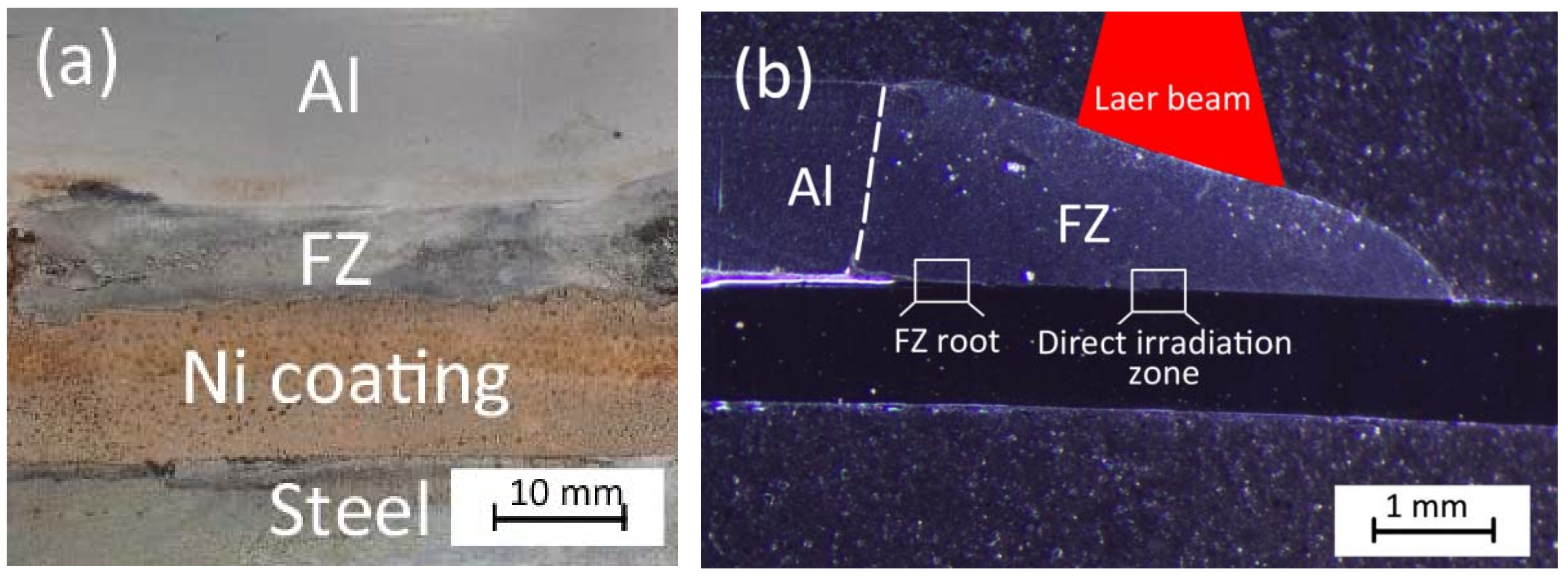

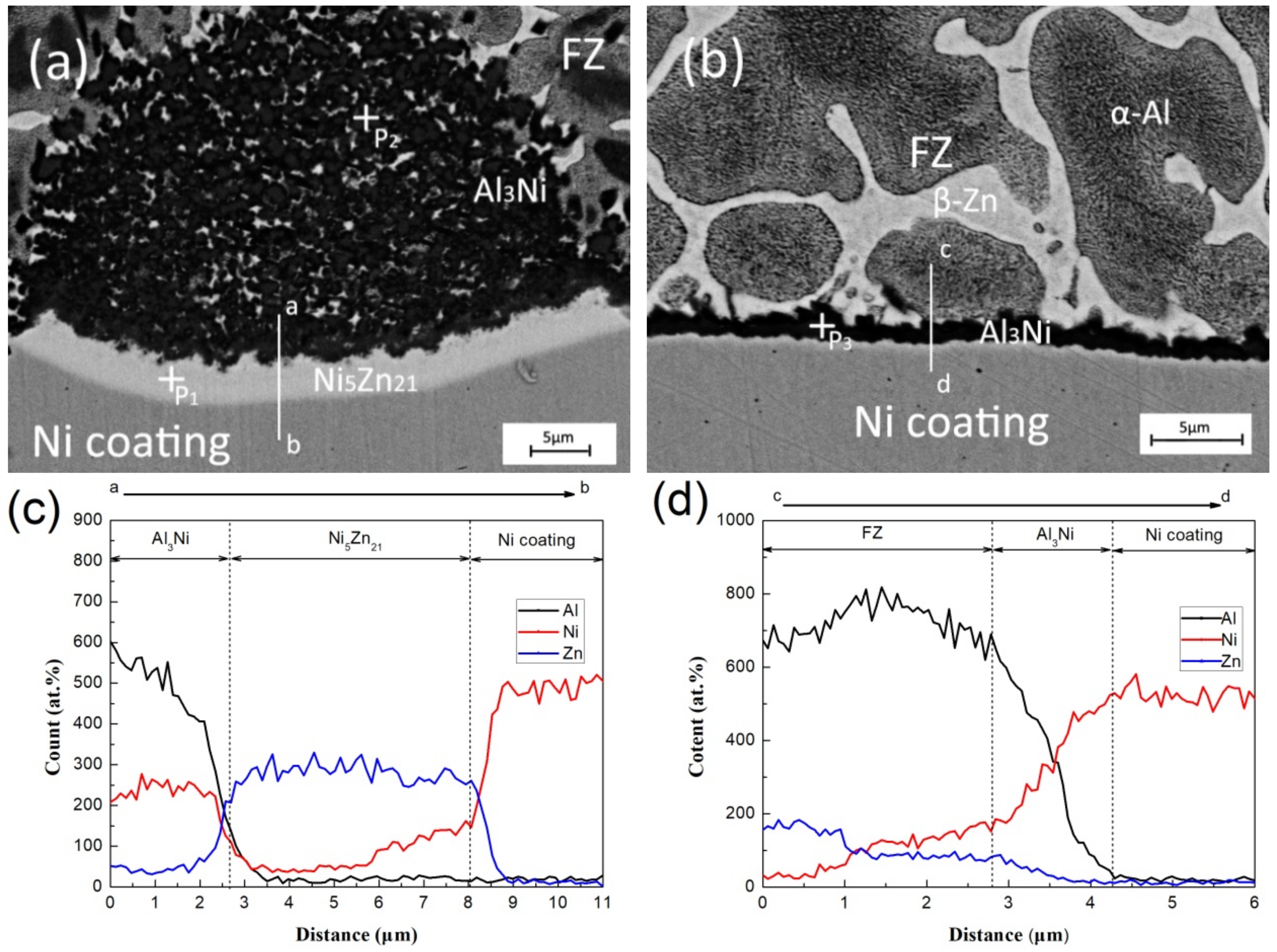

3.1. Microstructures

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.3. Fractography

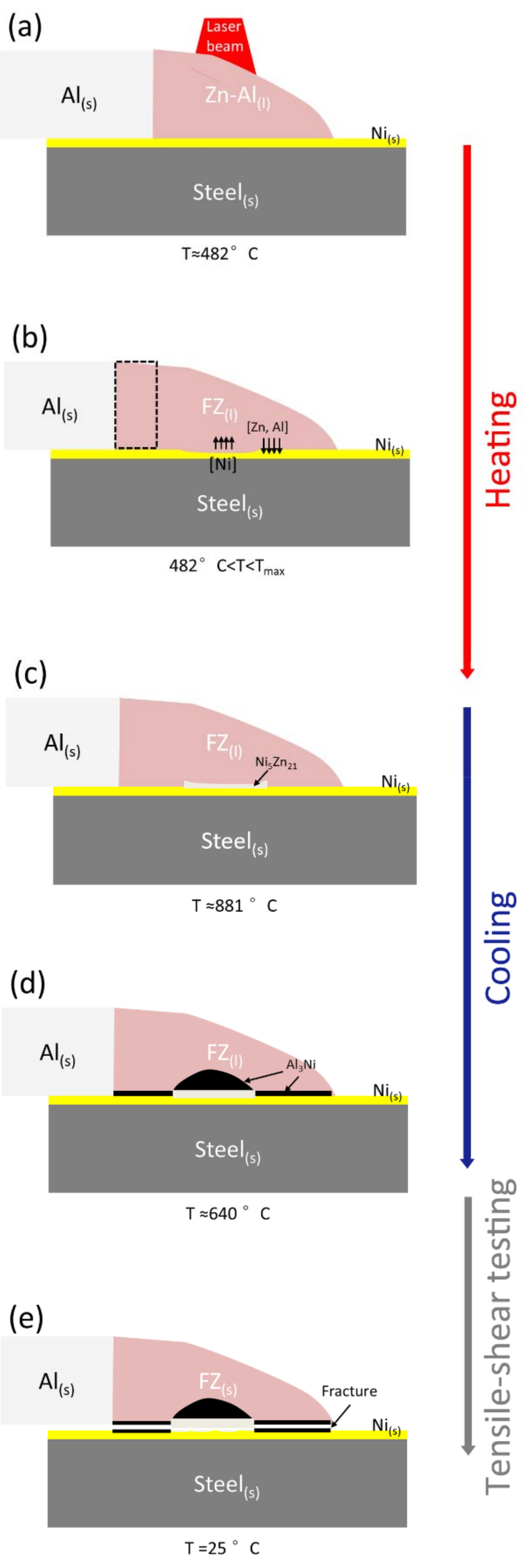

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

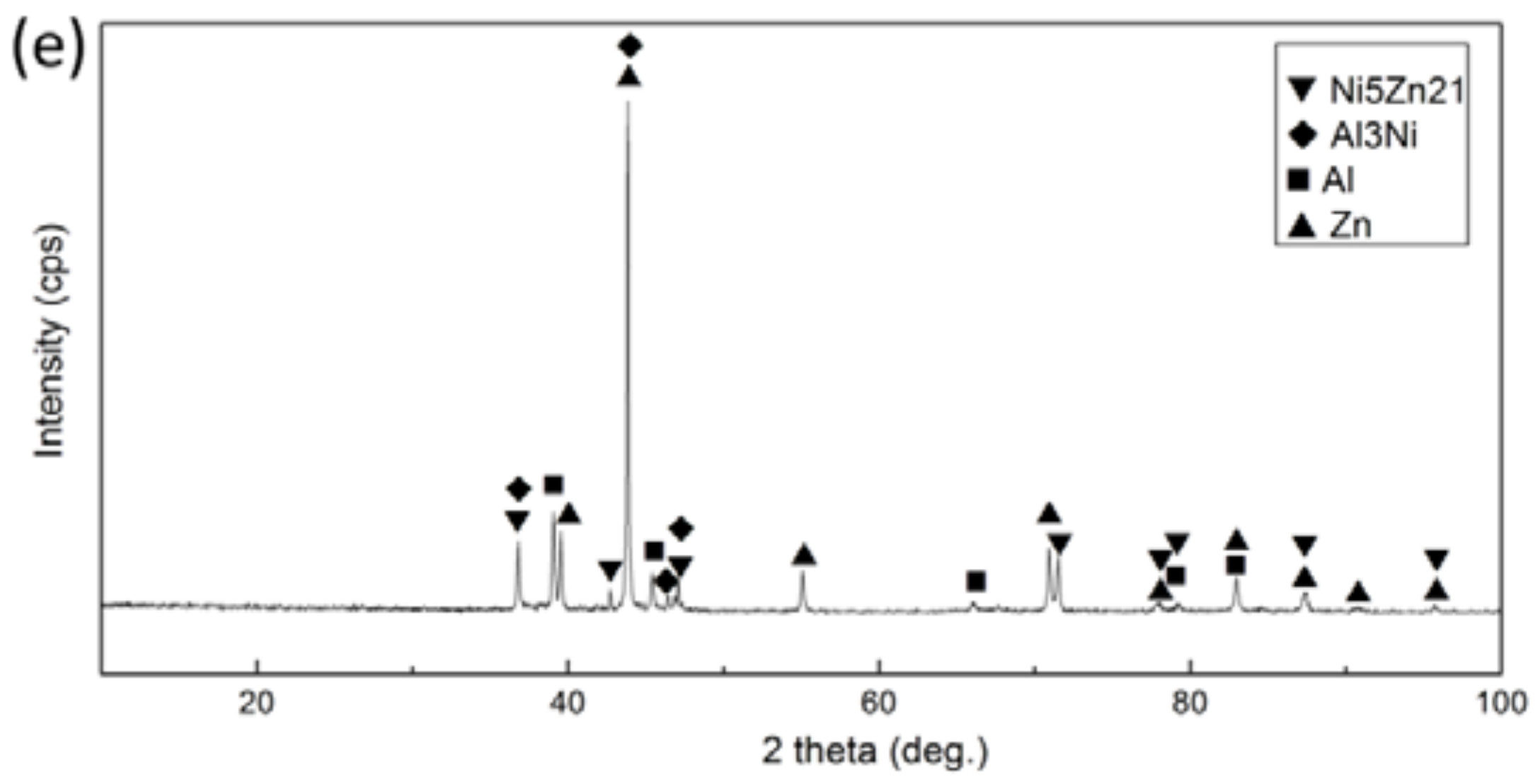

- For the Al/Ni-coated steel joint, a nonhomogeneous reaction layer was observed at the interface: Ni5Zn21 formed at the direct irradiation zone, while Al3Ni formed at the FZ root.

- (2)

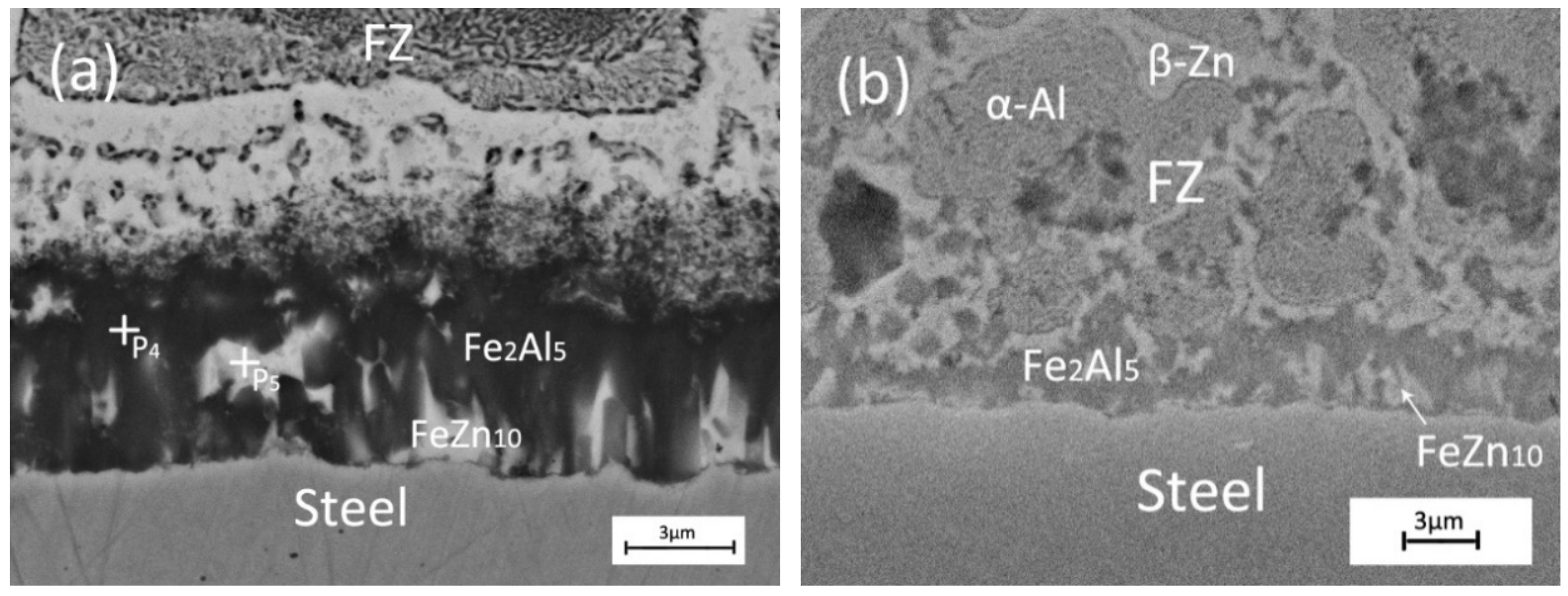

- For the Al/bare steel joint, a homogeneous reaction layer consisting of Fe2Al5 and FeZn10 was formed at the interface.

- (3)

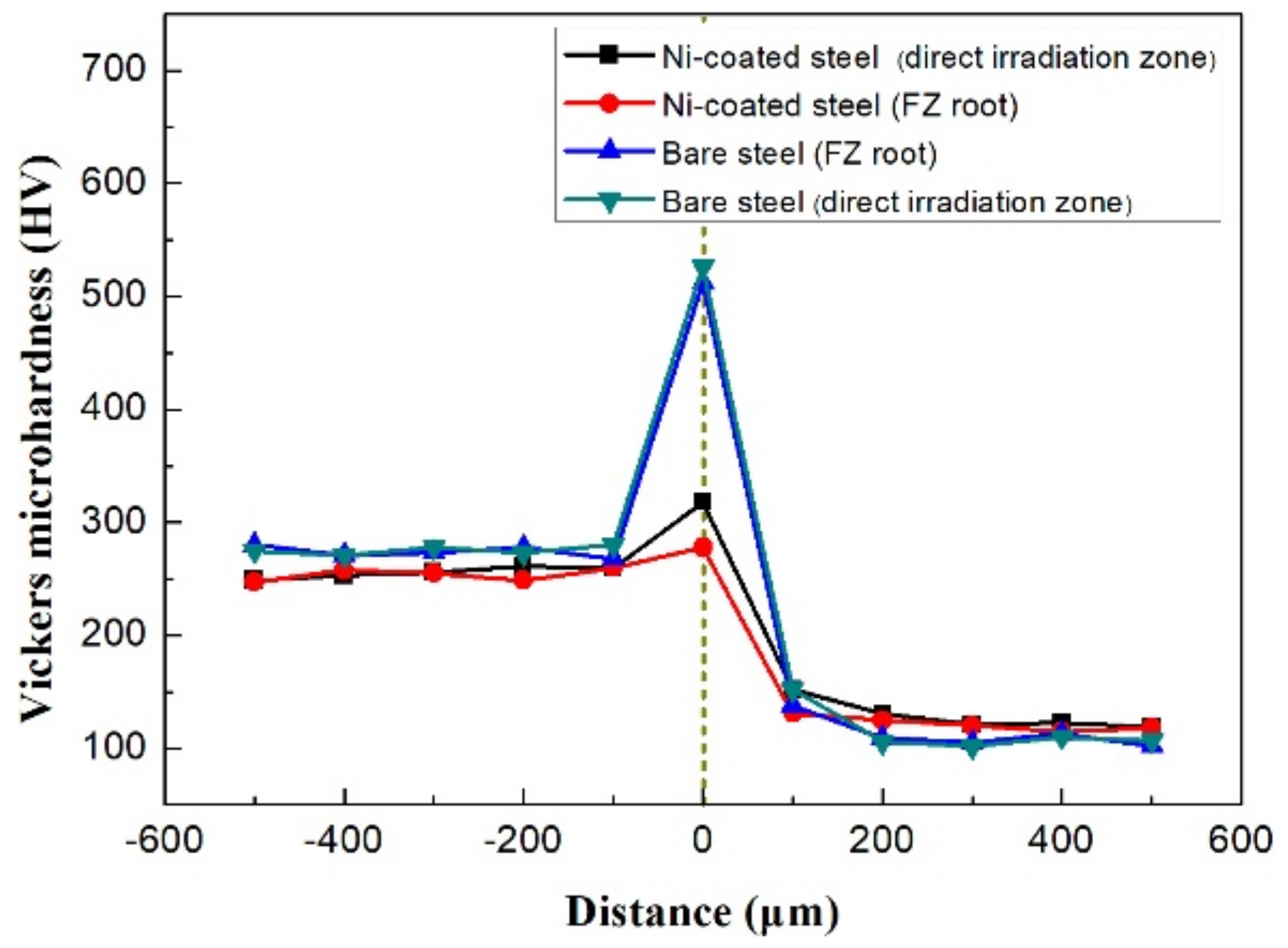

- The microhardness of the interfacial reaction layer in an Al/Ni-coated steel joint is 278–318 HV, which is much lower than that of the Al/bare steel joint (~512–526 HV).

- (4)

- The fracture load of the Al/bare steel joint was only 743 ± 65 N, but it improved to 932 ± 92 N by adding the Ni coating.

- (5)

- The Ni coating acted a physical barrier to avoid the direct mixing of elements Fe and Al, which inhibited the formation of brittle Fe2Al5. Hence, it led to the improvement of joint strength.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, W.; Wan, Z.; Peng, P.; Jia, Q.; Zou, G.; Peng, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of fiber laser welded QP980 steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 256, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Zhao, X.; Tan, C.; Chen, B.; Song, X.; Li, L. Effect of Si content on the interfacial reactions in laser welded-brazed Al/steel dissimilar butted joint. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 258, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbikain, G.; Perez, J.M.; López de Lacalle, L.N.; Andueza, A. Combination of friction drilling and form tapping processes on dissimilar materials for making nutless joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 232, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gerlich, A.P. Refill friction stir spot welding of dissimilar aluminum alloy and AlSi coated steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 30, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.A.; Macwan, A.; Bhole, S.D.; Chen, D.L.; Chen, X.G. Effect of welding energy on microstructure and strength of ultrasonic spot welded dissimilar joints of aluminum to steel sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 668, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarer, M.; Demir, B. An investigation of mechanical and metallurgical properties of explosive welded aluminum–dual phase steel. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 4158–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of pulsed laser welded Al/steel dissimilar joint. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Chang, J.H.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, X.B.; Yan, Y.J.; Chen, J.H. Behaviors and effects of Zn coating on welding-brazing process of Al-Steel and Mg-steel dissimilar metals. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 31, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Amirkhiz, B.S.; Liang, J.; Zhang, R. Formation of nanometer scale intermetallic phase at interface of aluminum-to-steel spot joint by welding–brazing process. Mater. Lett. 2014, 137, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhou, N. Influence of alloy elements on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al/steel dissimilar joint by laser welding/brazing. Weld. World 2018, 62, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, L.; Mi, G.; Jiang, P.; Shao, X.; Rong, Y. The influence of heat input on microstructure and mechanical properties for dissimilar welding of galvanized steel to 6061 aluminum alloy in a zero-gap lap joint configuration. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 726, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Ji, Y.; Ma, H.; Ao, Z. Effect of modified flux on MIG arc brazing-fusion welding of aluminum alloy to steel butt joint. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 245, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Lu, Q.; Chen, B.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y. Influence of laser power on microstructure and mechanical properties of laser welded-brazed Mg to Ni coated Ti alloys. Opt. Laser Technol. 2017, 89, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Niknejad, S.T.; Zhang, G.; Lee, M.K.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of resistance spot welded AZ31/AA5754 using a nickel interlayer. Mater. Des. 2015, 87, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, N. Laser welding/brazing of 5182 aluminium alloy to ZEK100 magnesium alloy using a nickel interlayer. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.P.; Panton, B.; Zeng, Z.; Andrei, C.M.; Zhou, Y.; Miranda, R.M.; Fernandes, F.B. Laser joining of NiTi to Ti6Al4V using a niobium interlayer. Acta Mater. 2016, 105, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Ma, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X. Influence of a Ni-foil interlayer on Fe/Al dissimilar joint by laser penetration welding. Mater. Lett. 2012, 79, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Ma, K.; Zhao, X.; Vivek, A. Microstructures and mechanical properties of laser penetration welding joint with/without Ni-foil in an overlap steel-on-aluminum configuration. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, 3064–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Weckman, D.; Zhou, N. Dissimilar laser welding/brazing of 5754 aluminum alloy to DP 980 steel: Mechanical properties and interfacial microstructure. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 5149–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tan, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, W.; Hu, X. Influence of Zn coating on interfacial reactions and mechanical properties during laser welding-brazing of Mg to steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2012, 43, 4740–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Y. Control of interfacial intermetallic compounds in Fe–Al joining by Zn addition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 645, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Tu, H.; Su, X. The 600 °C Isothermal Section of the Al-Ni-Zn Ternary System. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2017, 38, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, V. Al-Fe-Zn (Aluminum-Iron-Zinc). J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2013, 34, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H. Ni-Zn (nickel-zinc). J. Phase Equilib. 2003, 24, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H. Al-Ni (aluminum-nickel). J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2004, 25, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Mg | Cr | Mn | Si | Cu | Zn | Ti | Fe | Mo | C | Al | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP 980 steel | - | 0.15 | 2.1 | 0.05 | - | - | - | Bal. | 0.35 | 0.135 | 0.45 | 0.007 |

| Al 5754 | 2.6–3.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.4 | - | - | Bal. | - |

| Zn-22Al | - | - | - | - | <0.003 | Bal. | - | <0.02 | - | - | 22 | - |

| Materials | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP980 steel | 666 ± 36 | 1005 ± 7 | 12.5 ± 0.7 |

| Al 5754 | 85 ± 11 | 239 ± 3 | 16.2 ± 1.3 |

| Plating Solution Composition (g/L) | Electrodeposition Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NiSO4·6H2O | 180 | Cathode current density | 300 mA/mm2 |

| NH4Cl | 25 | Temperature | 43–60 °C |

| H3BO3 | 30 | pH | 5.6–5.9 |

| Time | 10–25 min | ||

| Welding Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Laser power (kW) | 2.6 |

| Defocusing amount (mm) | 3 |

| Welding speed (m/min) | 0.5 |

| Flow rate of shielding gas Ar (L/min) | 15 |

| Point | Al | Fe | Zn | Ni | Possible Phases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | - | 74.4 ± 0.3 | 19.4 ± 0.5 | Ni5Zn21 |

| P2 | 68.9 ± 0.9 | - | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 27.6 ± 0.4 | Al3Ni |

| P3 | 69.5 ± 5.1 | - | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 23.2 ± 4.5 | Al3Ni |

| P4 | 71.6 ± 0.5 | 23.8 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | - | Fe2Al5 |

| P5 | 10.8 ± 3.6 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 79.5 ± 3.1 | - | FeZn10 |

| Area | Al | Zn | Ni | Possible Phases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

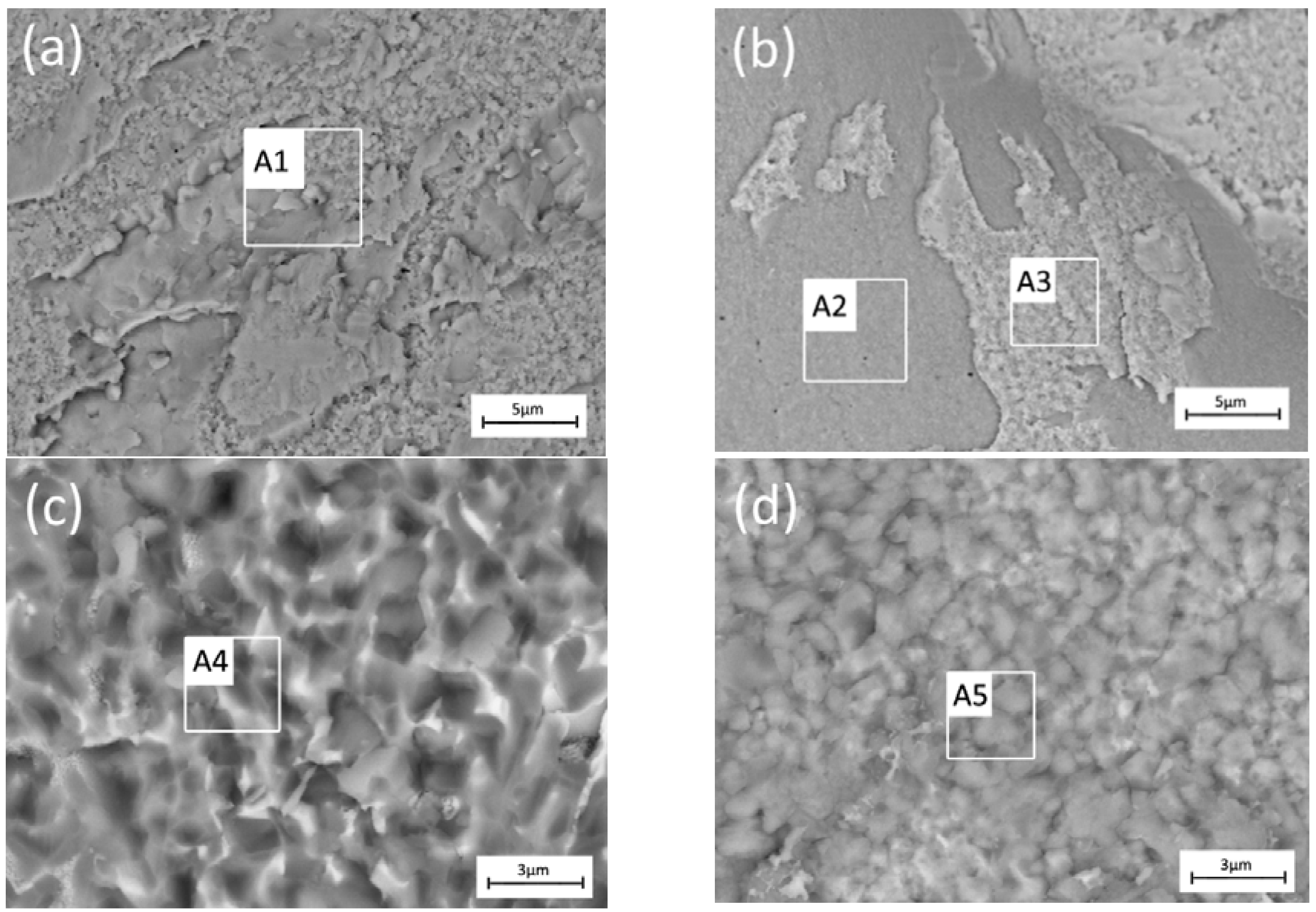

| A1 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 74.0 ± 2.7 | 23.1 ± 3.0 | Ni5Zn21 |

| A2 | - | - | 100.0 | Ni |

| A3 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 72.2 ± 1.8 | 21.9 ± 1.6 | Ni5Zn21 |

| A4 | 64.5 ± 2.5 | 8.5 ± 3.3 | 27.0 ± 1.3 | Al3Ni |

| A5 | 66.1 ± 2.3 | 10.0 ± 3.1 | 23.9 ± 2.2 | Al3Ni |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, N. Diode Laser Welding/Brazing of Aluminum Alloy to Steel Using a Nickel Coating. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060922

Yang J, Chen J, Zhao W, Zhang P, Yu Z, Li Y, Zeng Z, Zhou N. Diode Laser Welding/Brazing of Aluminum Alloy to Steel Using a Nickel Coating. Applied Sciences. 2018; 8(6):922. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060922

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jin, Jieshi Chen, Wanqin Zhao, Peilei Zhang, Zhishui Yu, Yulong Li, Zhi Zeng, and Norman Zhou. 2018. "Diode Laser Welding/Brazing of Aluminum Alloy to Steel Using a Nickel Coating" Applied Sciences 8, no. 6: 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060922

APA StyleYang, J., Chen, J., Zhao, W., Zhang, P., Yu, Z., Li, Y., Zeng, Z., & Zhou, N. (2018). Diode Laser Welding/Brazing of Aluminum Alloy to Steel Using a Nickel Coating. Applied Sciences, 8(6), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060922