1. Introduction

Basalt, as a mineral material, can be obtained from volcanic rocks which are originated from frozen lava with a melting temperature in the range of 1500 °C to 1700 °C [

1]. Basalt fiber was originally developed by the former Soviet Union and its first industrial production furnace was finished at Ukraine fibre laboratory in 1985 after 30 years of research and development [

2]. The manufacturing process of basalt fiber is similar to glass fiber, but less energy and no additives are needed. Therefore, basalt fiber is in principle cheaper than glass fiber and it is also suitable to produce chopped or continuous fibers [

3]. The cost of the final products also depends on the raw materials, the production process and the demanded mechanical and physical properties [

4]. Although asbesto and basalt fiber have a similar composition, the latter has different morphology and surface properties which avoid carcinogenic or toxicity effects [

5]. Kogan et al. [

6] and McConnell et al. [

7] both verified the safety of basalt fiber by animal experiments. Compared to glass fiber, basalt fiber shows similar mechanical properties and several advantages (see

Table 1). Therefore, it has been considered as an alternative reinforcement for composite materials which can be used in marine, automotive, sporting equipment and civil sectors [

8].

In addition to basalt fiber, several types of plant fibers have also been considered as the reinforcements for panels and semi-structural components, with the idea to improve the material biodegradability and the end-of-life scenarios. Among them, jute and hemp fibers are increasingly hybridized for use in the recent years, with the aim to exploit their advantages such as lightweight, nonabrasive, combustible, nontoxic, low cost and biodegradable properties. Although jute/hemp fibers polymer composites have acceptable mechanical properties for many applications such as furnitures, they are still not suitable to some specific fields such as acting as a type of building material.

In this regard, particleboards (PBs) and medium density fiberboards (MDFs), which are practical and cheap alternatives to solid wood, have become leading building materials in the past decade [

9]. PB is a type of panel product made of sawdust and wood shavings bonded together by synthetic resin and pressed into sheets. However, the availability of wood residues restricts its development. In addition, formaldehyde, which is used as the resin material during the manufacturing process, is a type of carcinogen. Therefore, it is necessary to consider alternative post-consumer waste wood or waste paper or agricultural residues as raw materials and more benign resins [

10]. This also offers environmental benefits such as diversion of waste from landfills or burning. Among the agricultural residues, bagasse is one of the largest non-wood lignocellulose by-products which is left after the crushing and extraction of the juice from the sugarcane [

11].

Similarly to conventional composite structures, the strength properties in the transverse direction of PBs are limited and therefore they have poor impact resistance. Low-velocity impact is usually considered as a major threat to fiber-reinforced polymer composite structures. Such foreign object loading can occur during manufacturing, assembly, maintenance and operation. The impact damage can significantly reduce the residual mechanical properties of composites even though it is hardly visible. The impact damage is becoming increasingly essential for the behavior of natural fiber composites, as they are usually reported to exhibit a limited resistance to impact loading.

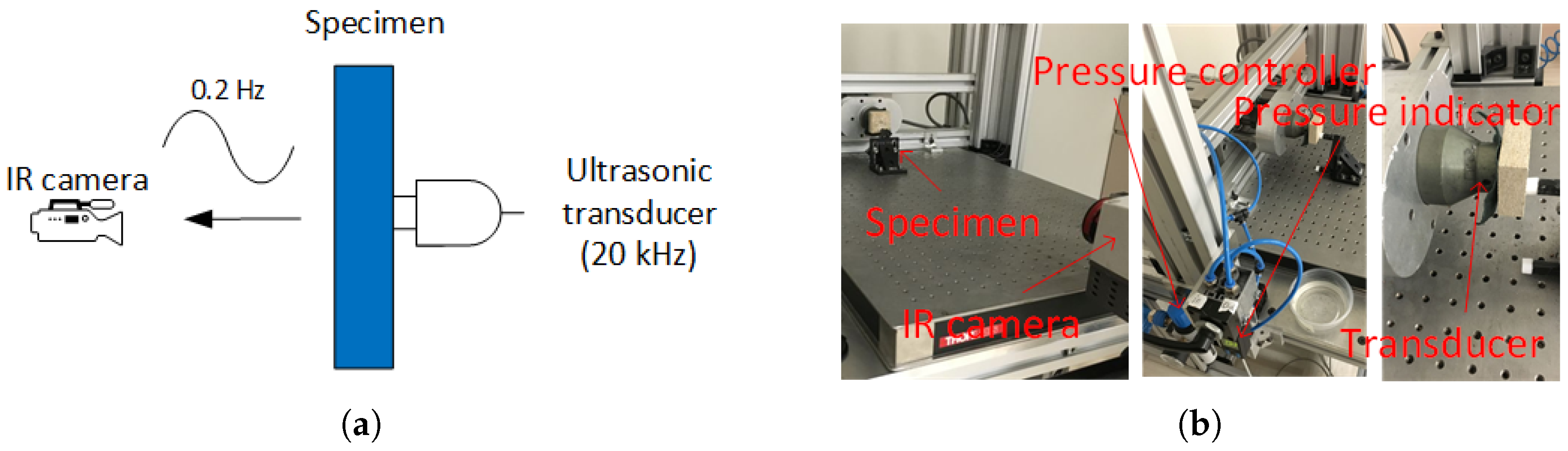

In addition to impact damage, some other manufacturing flaws such as porosities are also threats to the quality of the final product. In this regard, non-destructive testing (NDT) has been used for the evaluation of impact damage and overall quality in composite structures. The main NDT methods involve ultrasound, x-ray and infrared radiation etc. Ultrasound is a conventional and effective method for composite panels such as carbon fiber-reinforced polymer plastic (CFRP). It needs wedge such as water with the aim to get rid of air, but most of the plan fiber polymer composite materials are not water-proof. Air-coupled ultrasound has been developed, but it cannot penetrate thick materials which are often used in plant fiber composite applications. X-ray computed tomography (CT) is expensive, time-consuming, harmful to human body, and its contrast is relatively low [

12].

Recently infrared thermography (IRT) is becoming increasingly attractive as a NDT method due to the fact that it has faster inspection-acquisition rate, higher spatial resolution and contrast, and it is contactless. The development of infrared image processing algothrims also enhances its advantages for use. It has been used in different fields such as electrical components, medical imaging, thermal comfort, in-line industrial monitoring, buildings, artworks, composite materials [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Although IRT has been applied in many fields, quantitative analysis is becoming increasingly important aside from inspection, which need further study, e.g., depth information, etc. [

19,

20].

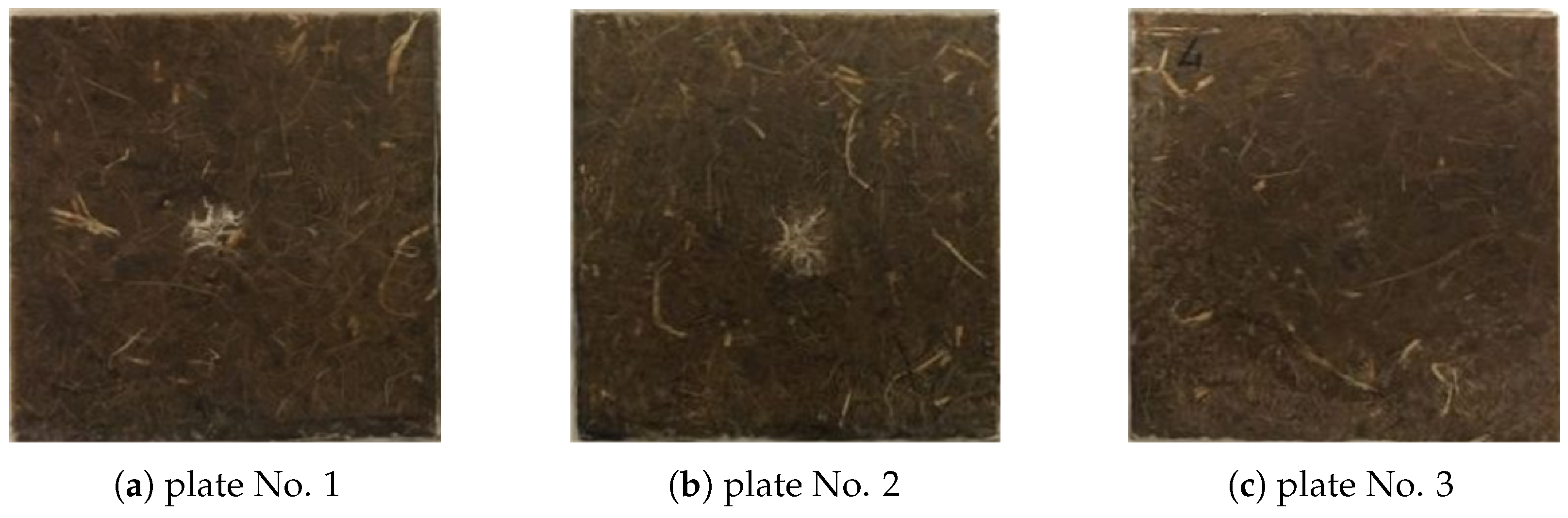

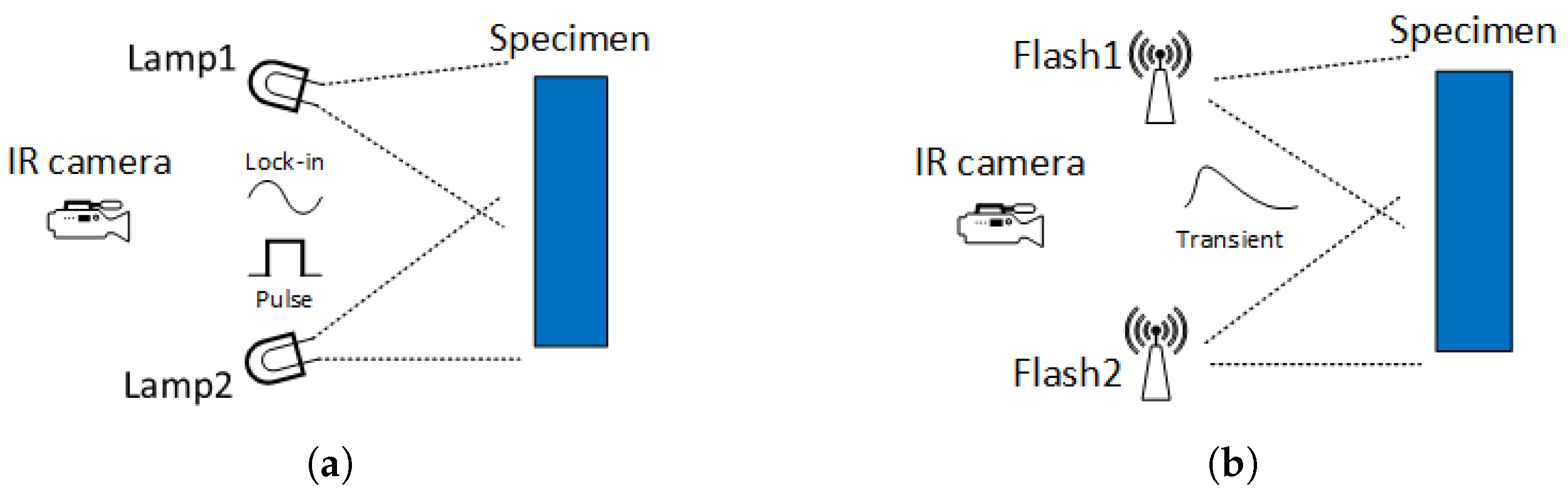

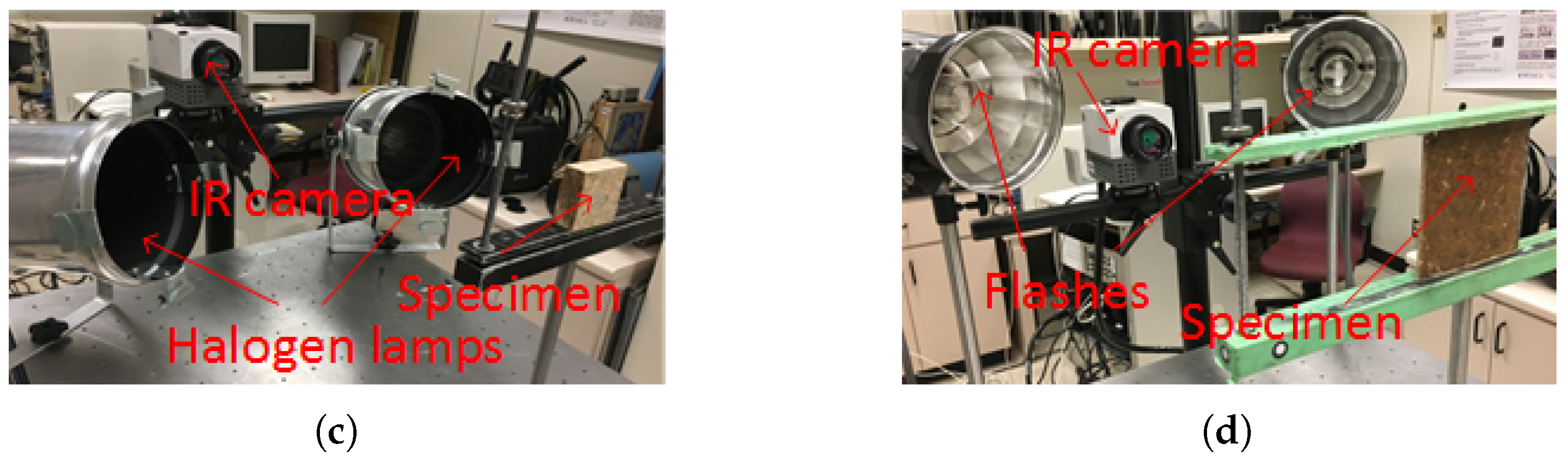

In this paper, IRT was used to evaluate impacted basalt fiber reinforced polymer laminates (BFRP), jute/hemp hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer laminates, and homogeneous particleboards of sugarcane bagasse (SCB). Different types of defects were analyzed in terms of impact damage, delaminations and resin abnormalities. Of particular interest, SCB is a new type of PB made of bagasse fibers and bio-resins derived from castor oil. Pulsed phase thermography (PPT) and principal component thermography (PCT) were used to process the raw data. Ultrasonic C-scan testing (UT) and emerging continuous wave terahertz (CW THz) imaging were used on the mineral fiber laminates for comparative purposes. Finally, an analytical comparison of different thermographic techniques for natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites inspection was given.

4. Infrared Image Processing

Principal component thermography (PCT) [

33] has been used as an infrared image processing technique to extract the image features and reduce undesirable signals. Different from classical principal component analysis, PCT relies on singular value decomposition (SVD) which extracts spatial and temporal data from a matrix in a compact manner by projecting original data onto empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs). Original data can often be adequately represented with only a few EOFs. Usually, an infrared sequence of 1000 images can be replaced by 10 or less EOF [

34]. Another advantage of PCT is its suitability to be combined with other image processing techniques, e.g., in [

35,

36,

37].

Fast Fourier transform can be used to extract amplitude and phase information from the raw thermal data. It provides the possibility to obtain quantitative results in a straightforward manner. Usually phase is more useful than amplitude because it can retrieve the deeper information. In addition, phase is less affected than raw and amplitude data by environmental reflections, emissivity variations, non-uniform heating, surface geometry and orientation [

27]. This method has been used for LT and it is known as phase transform. When used for PT, it is known as pulsed phase thermography (PPT) [

38].

The relationship exists between the depth

z of a defect and the thermal diffusion length

. Empirical expressions have been proposed [

39]:

where,

is known as the blind frequency - the frequency at which a given defect has enough (phase or amplitude) contrast to be detected, and

is an empirical constant.

It has been observed that

1 for amplitude transform [

40], while reported values for phase transform are in the range of 1.5 to 2 [

40], with

= 1.82 typically adopted [

41]. Therefore, phase transform is more important than amplitude because it can access the deeper information [

27].

According to Equation (

1), the thermal diffusivity

is a parameter of particular importance for calculating the depth by PPT.

can be expressed as follows:

where

(J/kgK) is the specific heat at constant pressure,

(kg/m

3) is the density, and

k (W/mK) is the thermal conductivity.

For composite materials,

can be calculated by:

where N is the number of constituent materials in the composites.

Therefore, the thermal diffusivity

can be obtained by calculating

,

and

k in

Table 5.

In this paper, recursive median filter (RMF) and cold image subtraction (CIS) [

42] were used as the pre-processing methods.

Table 6 shows the applied experimental and image processing methods for different specimens.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

Figure 8 shows the PT results of BFRP. PPT was performed and then the depth information was obtained by Equations (

1) and (

2) using the physical properties in

Table 5. The images from the depths of 0.28 mm (0.6 Hz), 0.85 mm (0.065 Hz) and 1 mm (0.048 Hz) were obtained in flashes and halogen lamps modalities, respectively.

In

Figure 8a,b, the resin-rich areas A and C were detected at the depth of 0.28 mm, and were barely detected at the depths of 0.85 mm (

Figure 8d,e), then were not detected at all at the depth of 1 mm (

Figure 8g,h). The resin-rich areas B and F were detected at the depth of 0.85 mm (

Figure 8d,f) in the clearest view; they were not detected at the depth of 1 mm (

Figure 8g,i). The delamination in

Figure 8h (marked in purple) was detected at the depth of 1 mm, which suggests its depth. The impact damage (marked in yellow) grew along with the depth increase. Overall, flashes modality provided clearer results than halogen lamps modality, and PPT can provide the additional information. In particular, it can provide the depth information via frequencies for quantitative analysis, which is advantageous.

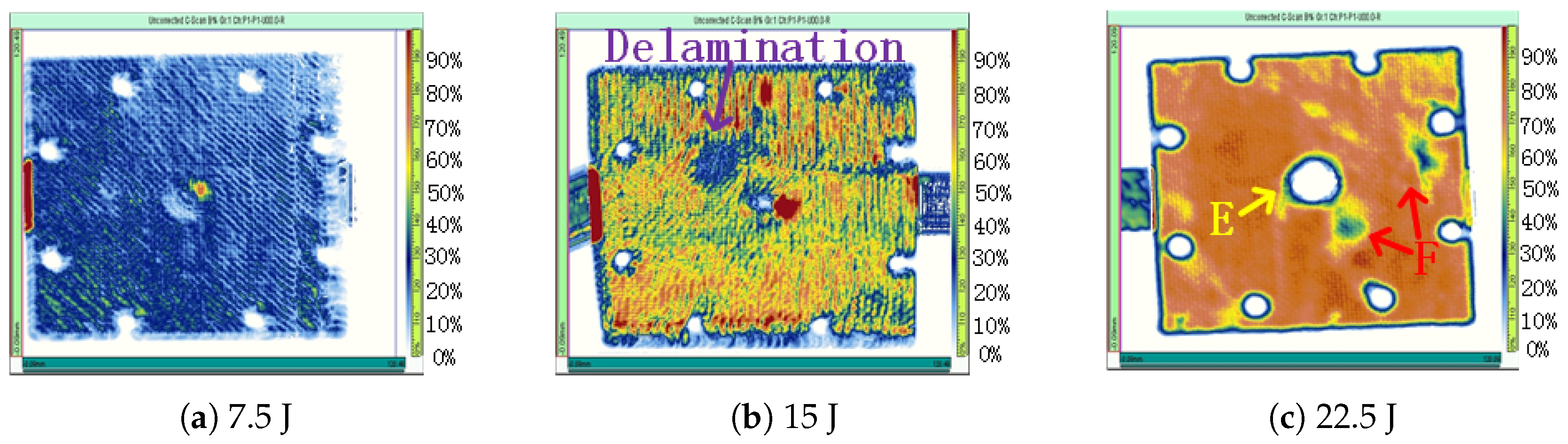

Taking into account the UT results in

Figure 9, the PT results evidently provided more information, especially for resin-rich areas (marked in red). The VT results in

Figure 10 only showed clear identification for delamination, but not for resin-rich and impact damage areas.

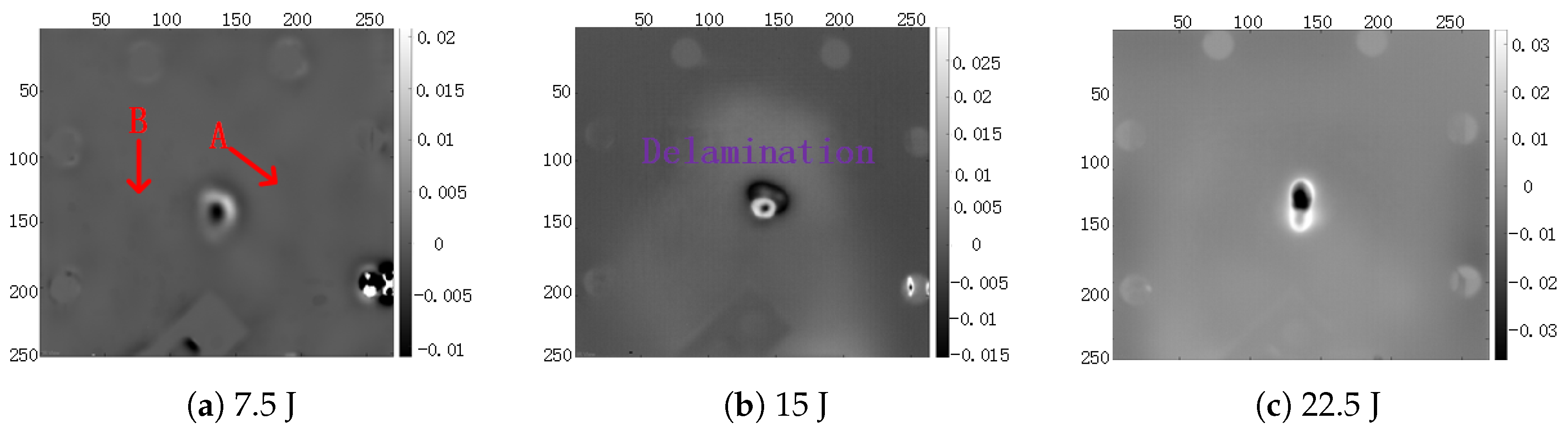

The delamination was shown more clearly in the front-side inspection in

Figure 11. PPT provided additional information (

Figure 11e–g, in which the delamination shrinked along with the depth increase. CW sub-THz can detect the delamination, but showed a rough result (

Figure 11c). This may be caused by the low resolution (∼3 mm) linked to its low radiation frequency (∼0.1 THz). The depth information in CW inspection is inaccessible. The intensity curve of the CW sub-THz result in

Figure 11d showed the delamination feature, which is deepest in the central zone. The fiber information was not detected in BFRP.

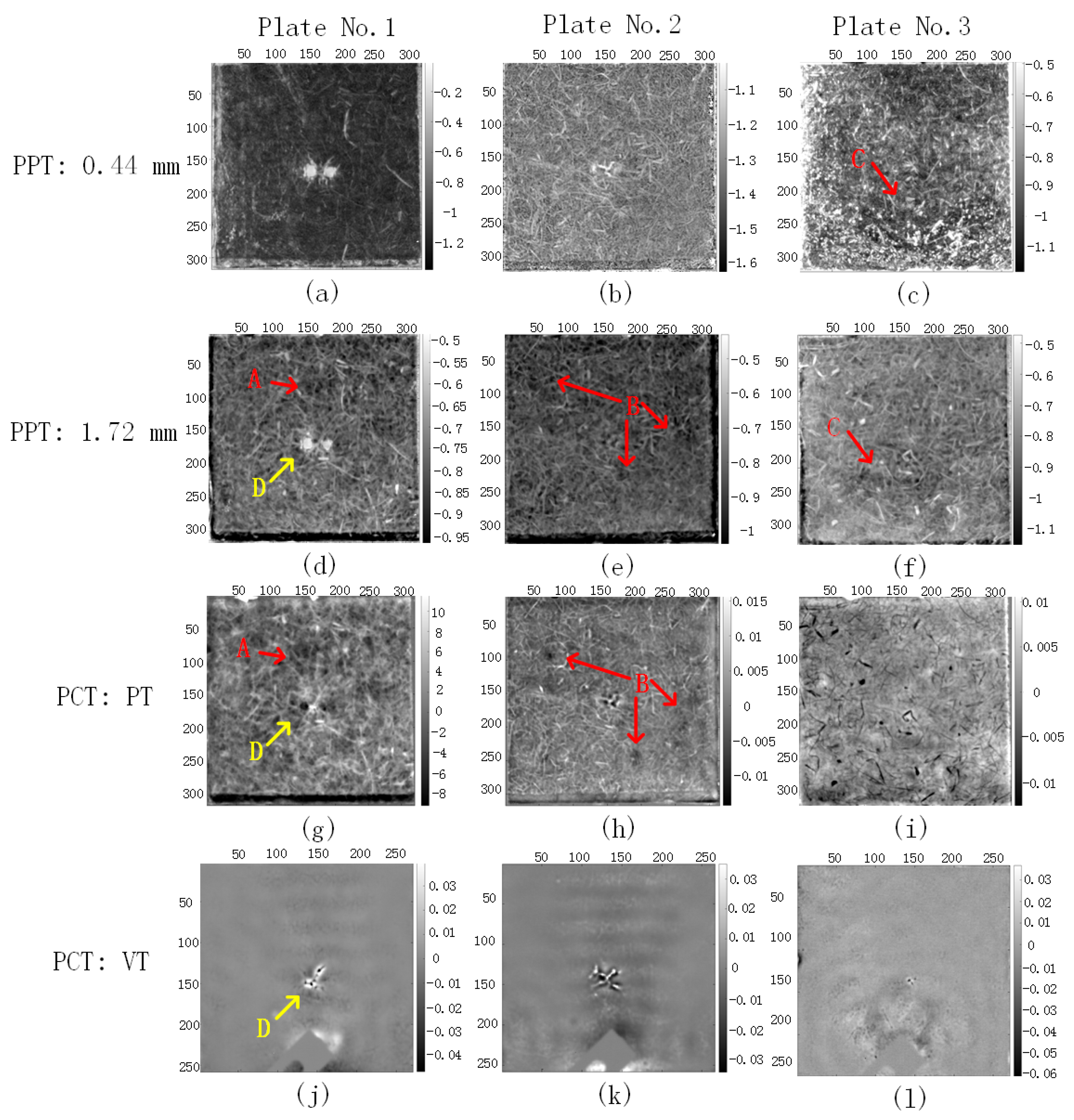

Figure 12 shows the thermographic results of jute/hemp hybrid laminates. The results are linked to the flashes modality because it provides clearer results, and the full thickness can be detected due to the higher thermal diffusivity

. The images from the depths of 0.44 mm (1 Hz) and 1.72 mm (0.066 Hz) were obtained by PPT. Impact damage areas (marked in yellow) other than the visible zones were detected, but not as clear as that in BFRP. The resin-rich areas (marked in red) were clearly detected. The fibers can be identified very clearly, which provides the possibility for the evaluation of fiber orientation. PPT (

Figure 12a–f) provided more information than PCT (

Figure 12g–i) and VT (

Figure 12j–l), especially for the identification of the flaws by means of defect depth retrieval via frequencies. PCT showed the clear identification for both resin-rich and impact damage areas, but the impossibility to perform a quantitative analysis is the disadvantage. VT only showed the impact damage areas, although additional information of resin-rich areas and fibers can be visualized.

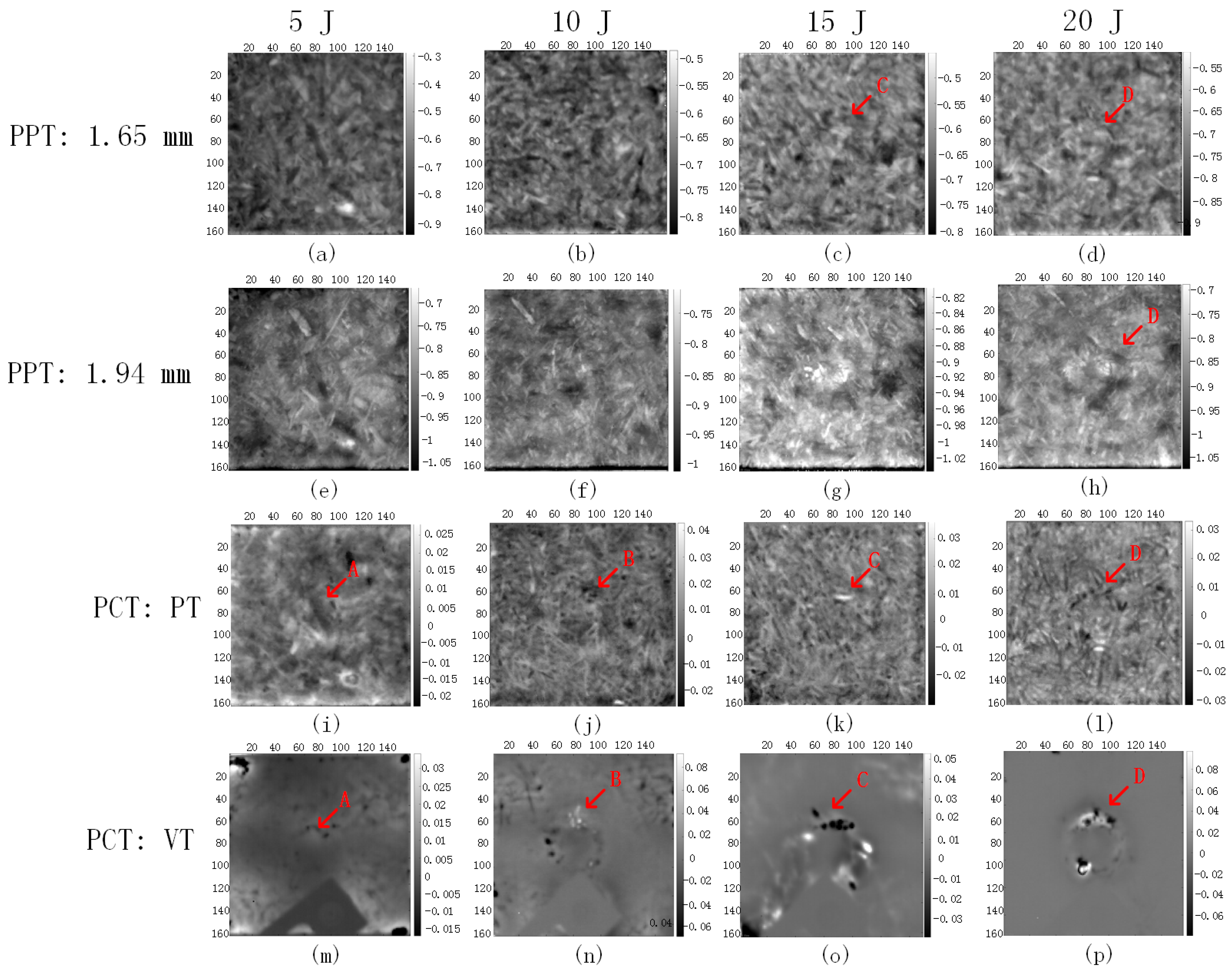

Figure 13 shows the thermographic results of SCB. The images from the depths of 1.65 mm (0.066 Hz) and 1.94 mm (0.048 Hz) were obtained. The resin-rich areas were detected, and the fibers can be identified. The fiber orientation evaluation is more difficult in the case of SCB due to the thermal characteristics. The impact damage areas A and B in

Figure 13a,b,e,f were not detected at the depths of 1.65 mm and 1.94 mm because they are too close to the surface. The impact damage area C was detected at the depth of 1.65 mm in

Figure 13c, and the impact damage area D was detected at depths of both 1.65 mm and 1.94 mm in

Figure 13d,h. The depth information is a little bit deeper than the mechanical measurement because the thermal diffusivity

value was calculated using similar and reasonable data present in the scientific literature. Nevertheless, the growing trend of the impact damage areas coincides with the theoretical estimation. The impact damage areas in the four specimens can be detected by PCT. Of interest, VT showed the clearest results for the impact damage inspection of SCB.

Table 7 shows the relationship between modulated frequency

and depth

z according to Equation (

1) for phase-based LT.

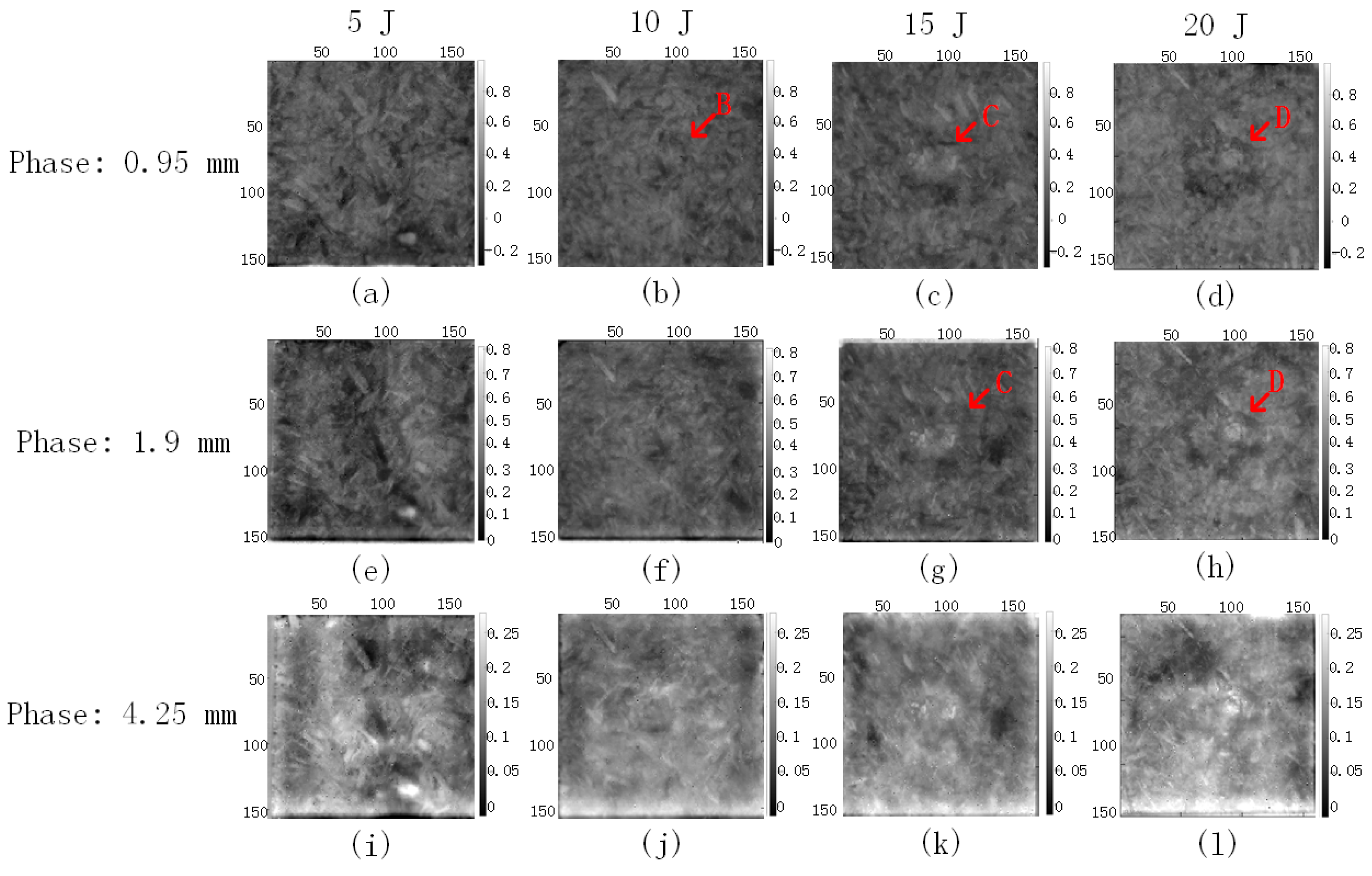

Figure 14 shows the LT (phase) results of SCB at depths of 0.95 mm, 1.9 mm and 4.25 mm. The impact damage area A was not detected at the depths of 0.95 mm and 1.9 mm in

Figure 14a,e because it is located so close to the surface. The impact damage area B was detected at the depth of 0.95 mm in

Figure 14b, but not at the depth of 1.9 mm in

Figure 14f, which coincides with the mechanical measurement. The impact damage areas C and D were detected at the depths of 0.95 mm (

Figure 14c,d) and 1.9 mm (

Figure 14g,h) which is due to the calculation of the thermal diffusivity

from literature data. All the impact damage areas were not detected at the depth of 4.25 mm. The growing trend of impact damage in SCB coincides with the theoretical estimation. The resin-rich areas were also detected by phase-based LT, which showed clearer results, but the longer inspection time is the disadvantage.