A Comprehensive Survey of Cybersecurity Threats and Data Privacy Issues in Healthcare Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Motivation

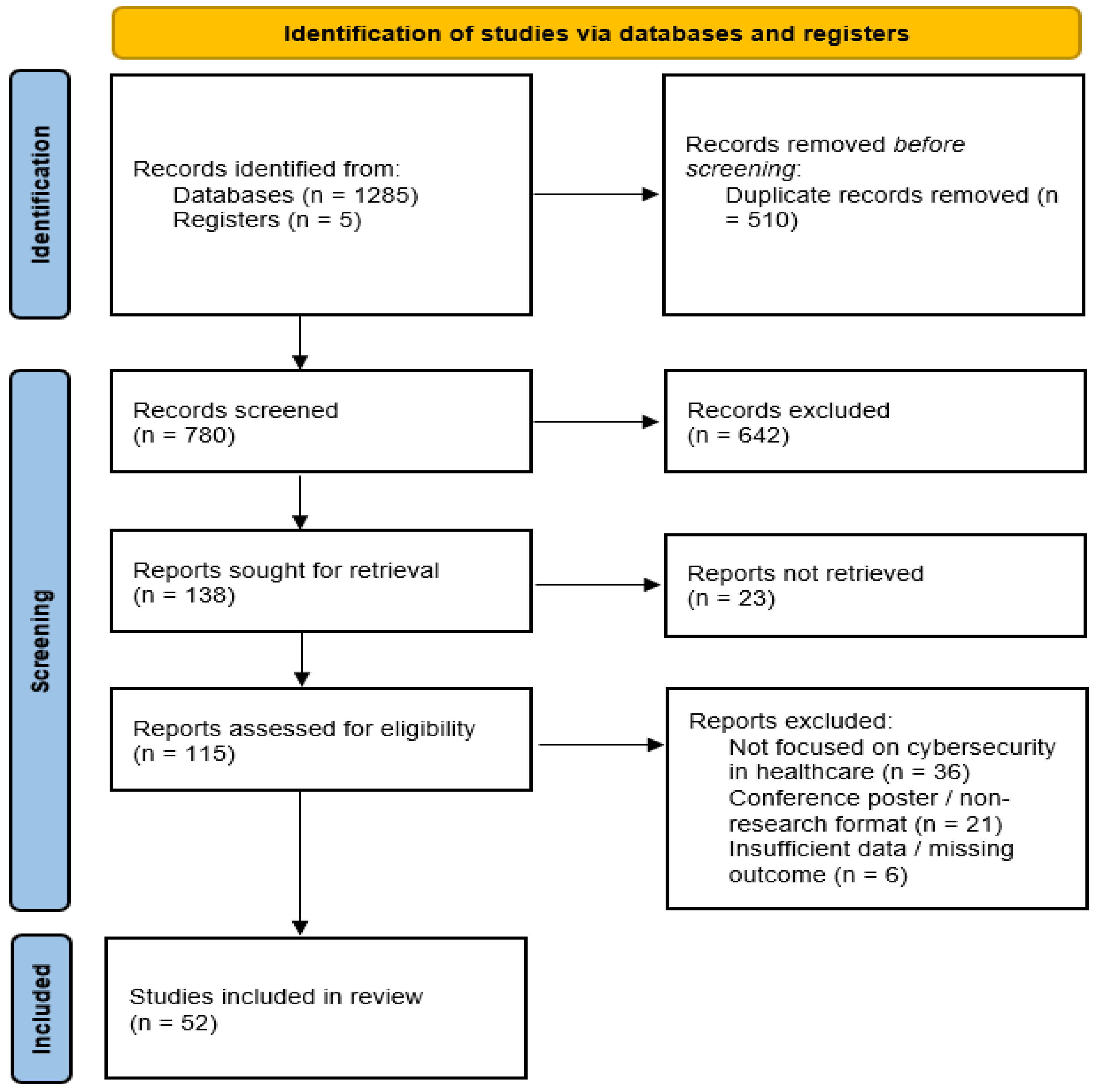

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Methodology Scope and Review Framework

3.2. Literature Search Strategy

3.3. Data Handling and Study Selection

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers.

- Studies focusing on cybersecurity threats and/or data privacy issues in healthcare systems.

- Publications proposing, analyzing, or reviewing technical, regulatory, or organizational security solutions in healthcare contexts.

3.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-peer-reviewed articles (e.g., editorials, opinion pieces, news items).

- Studies not specific to healthcare security or privacy.

- Duplicate publications or papers lacking sufficient technical or analytical detail to support synthesis.

3.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3.6. Quality and Bias Considerations

3.7. PRISMA-ScR–Aligned Review Process

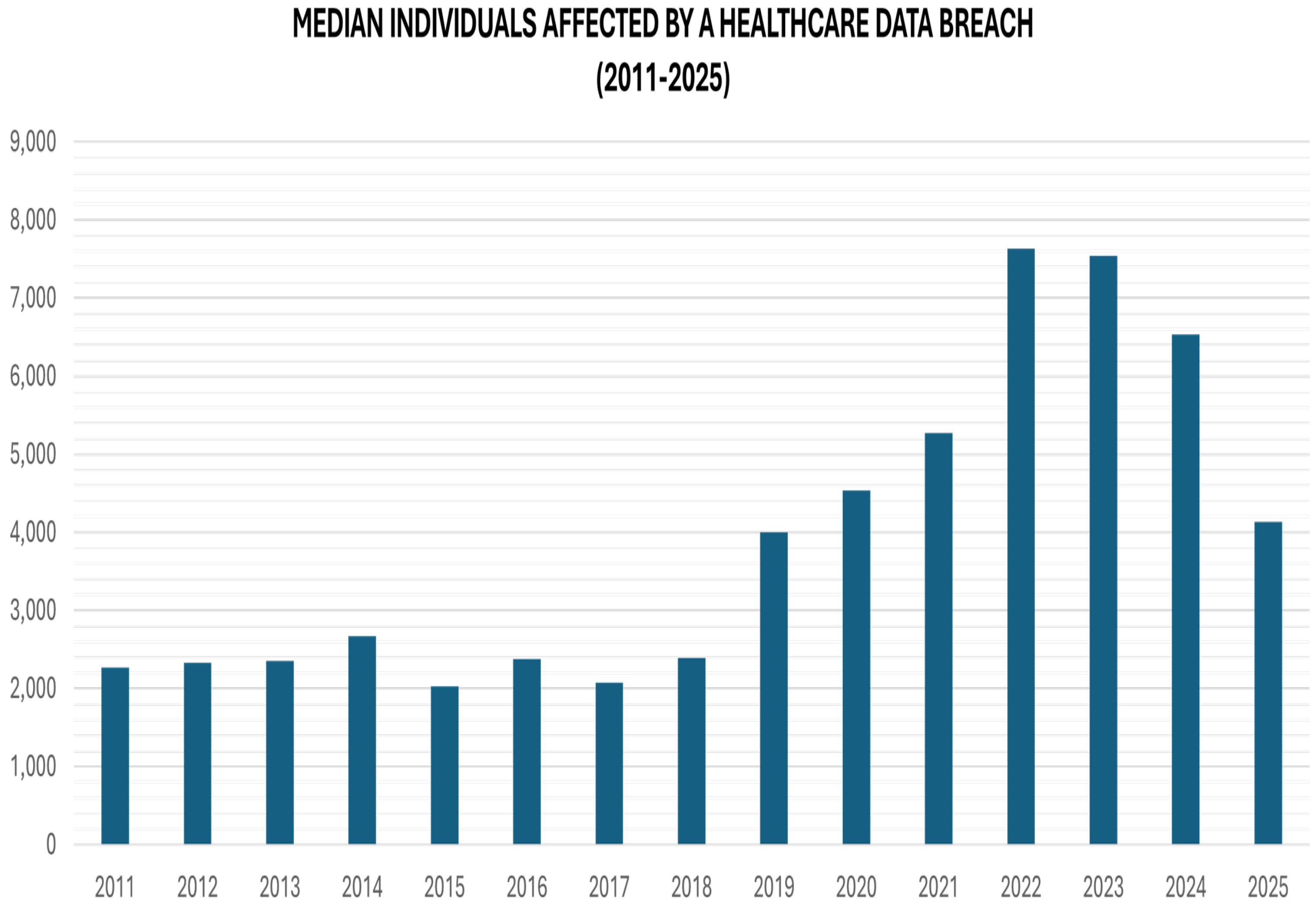

4. Cybersecurity Threat Landscape in Healthcare

4.1. Insider Threats

- Malicious Insiders: Malicious insiders are authorized users who intentionally misuse their access to harm healthcare systems or organizations. In healthcare environments, such threats often involve the deliberate theft of electronic health records (EHRs), intellectual property, or research data for financial gain, espionage, or personal motives. Studies report that malicious insiders may engage in data ex-filtration, system sabotage, or unauthorized disclosure of patient information, posing serious risks to patient privacy and institutional reputation. Although less frequent than other insider threat types, malicious insiders typically cause disproportionately high financial and reputational damage due to their deep system knowledge and privileged access. Detecting malicious insiders is challenging because their actions often resemble legitimate operational behavior until damage has occurred.

- Negligent Insiders: Negligent insiders are legitimate users who unintentionally cause security breaches due to carelessness or insufficient awareness. This category includes incidents such as lost devices, misdirected information, or improper handling of sensitive data. A common example is an employee accidentally sending PHI to the wrong recipient or failing to encrypt data. Although these actions are unintentional, they can be frequent, particularly among overburdened staff [22]. In healthcare systems, negligent behavior includes weak password practices, accidental data disclosure, improper configuration of systems, and falling victim to phishing attacks. Literature consistently identifies negligent insiders as the most common cause of healthcare data breaches, largely due to the complex workflows, high workload, and stress experienced by healthcare staff. Such incidents frequently result in large-scale exposure of sensitive patient data and regulatory non-compliance. Unlike malicious insiders, negligent insiders do not intend harm, making training, awareness programs, and usability-focused security controls critical for mitigation.

- Compromised Insiders: Compromised insider threats occur when attackers hijack legitimate user credentials, often through phishing, malware, or credential theft. In healthcare environments, compromised accounts are particularly dangerous because attackers gain access to sensitive systems while appearing as trusted users. Research shows that compromised insiders are responsible for a significant portion of large-scale healthcare breaches, as attackers can move laterally across networks, access EHRs, and deploy ransomware. These threats blur the boundary between insider and outsider attacks, as external adversaries operate under internal identities. Effective mitigation requires multifactor authentication, continuous behavior monitoring, and anomaly detection, as traditional perimeter-based defenses are insufficient.

Existing Mitigation Approaches for Insider Threats

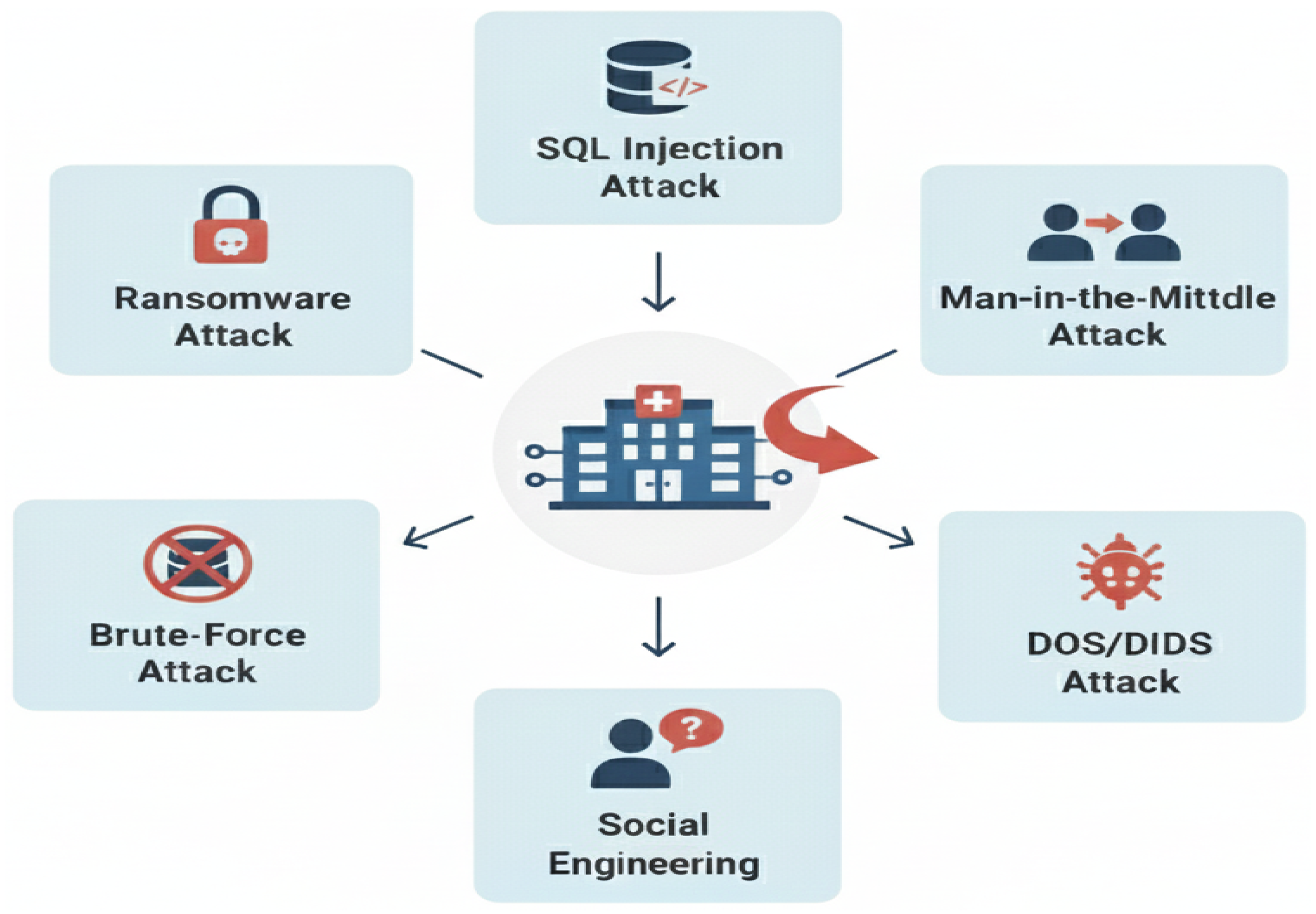

4.2. Outsider Threats

- Malware: In healthcare environments, malware represents a class of cyber threats involving harmful software intended to disrupt system functionality, extract sensitive patient information, or obtain unauthorized access to clinical networks and medical devices. Typical malware variants include ransomware, spyware, and trojans, which can interfere with electronic health records (EHRs), impair critical healthcare services, and pose direct risks to patient safety [29]. The extensive use of interconnected devices, along with the presence of legacy systems, further increases the susceptibility of healthcare infrastructures to malware-based attacks, making them a significant cybersecurity concern.Malware attacks generally involve the creation and deployment of malicious code or firmware that infiltrates systems under the guise of legitimate software. Once introduced, such code can manipulate or destroy data, perform intrusive actions, or otherwise compromise the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of system resources. Common malware categories include viruses, worms, trojan horses, rootkits, and other forms of malicious code capable of penetrating healthcare information systems [30].

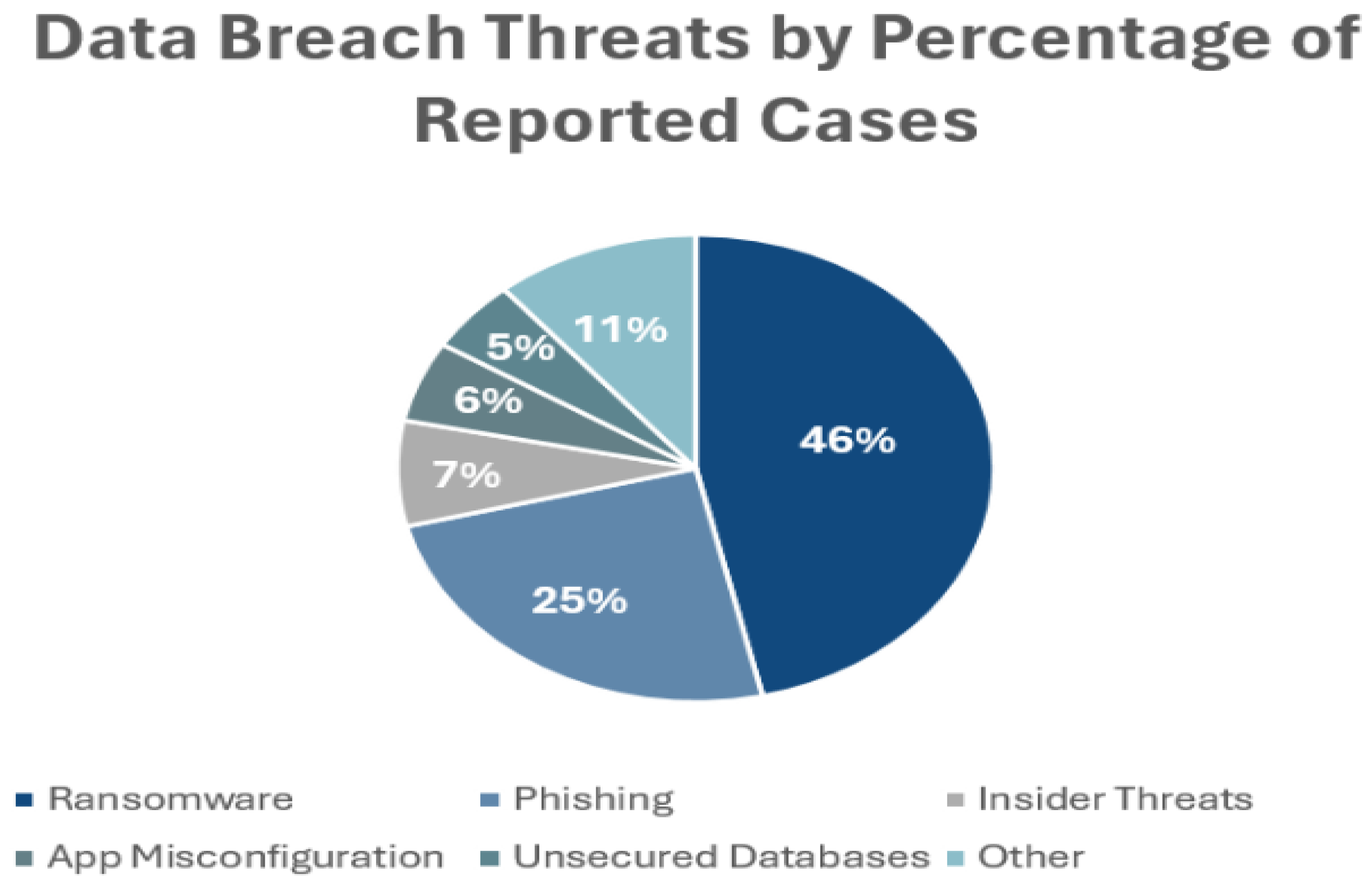

- Social Engineering/Phishing: Social engineering exploits the predictability of human behavior and plays a role in the majority of cyberattacks. It is also the fastest-growing attack vector, often described as increasing at an unprecedented rate. Social engineering is closely associated with data breaches, with approximately 95% of incidents linked to human error. The healthcare sector is particularly vulnerable, experiencing the highest average cost per breach, exceeding USD 7 million, surpassing all other industries. Globally, the projected economic impact of social engineering-related cyberattacks is expected to reach USD 10.5 trillion annually by 2025 [31].

- DoS/DDoS: The primary challenge facing m-health technologies is ensuring the security of medical and other sensitive data, with data availability being one of the most critical concerns. Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks pose a significant threat by disrupting continuous access to patient information and impeding data transmission across interconnected networks. Beyond data compromise, DDoS attacks can severely restrict authorized users from accessing essential healthcare services and information portals [32].Denial-of-service (DoS) attacks aim to disrupt services by overwhelming networks with excessive traffic, thereby preventing legitimate users from accessing critical systems. Such attacks can significantly degrade or completely shut down healthcare networks, severely impacting operational continuity. For instance, a DoS attack in 2014 temporarily disabled the administrative systems of Boston Children’s Hospital, resulting in substantial operational and financial losses. Beyond economic damage, these attacks critically hinder healthcare providers’ ability to access, transmit, and manage essential patient information during the attack period, posing serious risks to patient care and safety [31].

- Network Intrusion: Network intrusion in healthcare systems represents a critical cyber security threat due to the highly interconnected nature of modern clinical environments and the sensitivity of medical data. Attackers exploit vulnerabilities such as weak network configurations, un-patched systems, insecure remote access, and compromised credentials to gain unauthorized access to hospital networks [33]. Once inside, intrusions can enable lateral movement across clinical and administrative systems, allowing adversaries to ex-filtrate patient data, deploy ransomware, disrupt medical devices, or manipulate health records. These incidents not only compromise patient privacy but can also interrupt clinical workflows, delay diagnoses or treatments and pose direct risks to patient safety. The growing adoption of cloud services, tele-medicine platforms and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices further expands the attack surface, making robust intrusion detection systems, network segmentation, continuous monitoring and timely incident response essential components of healthcare cyber-security strategies.

- Brute Force: Brute-force attacks attempt to gain unauthorized access by repeatedly guessing username and password combinations. In-hospital management information systems, such attacks can lead to serious data breaches and financial losses due to the sensitivity of stored information. To mitigate these risks, healthcare organizations should enforce strong password policies, implement robust authentication and multi-factor authentication, encrypt patient data, and deploy effective monitoring and response mechanisms. These measures help secure hospital systems while ensuring the safe delivery of healthcare services [34].

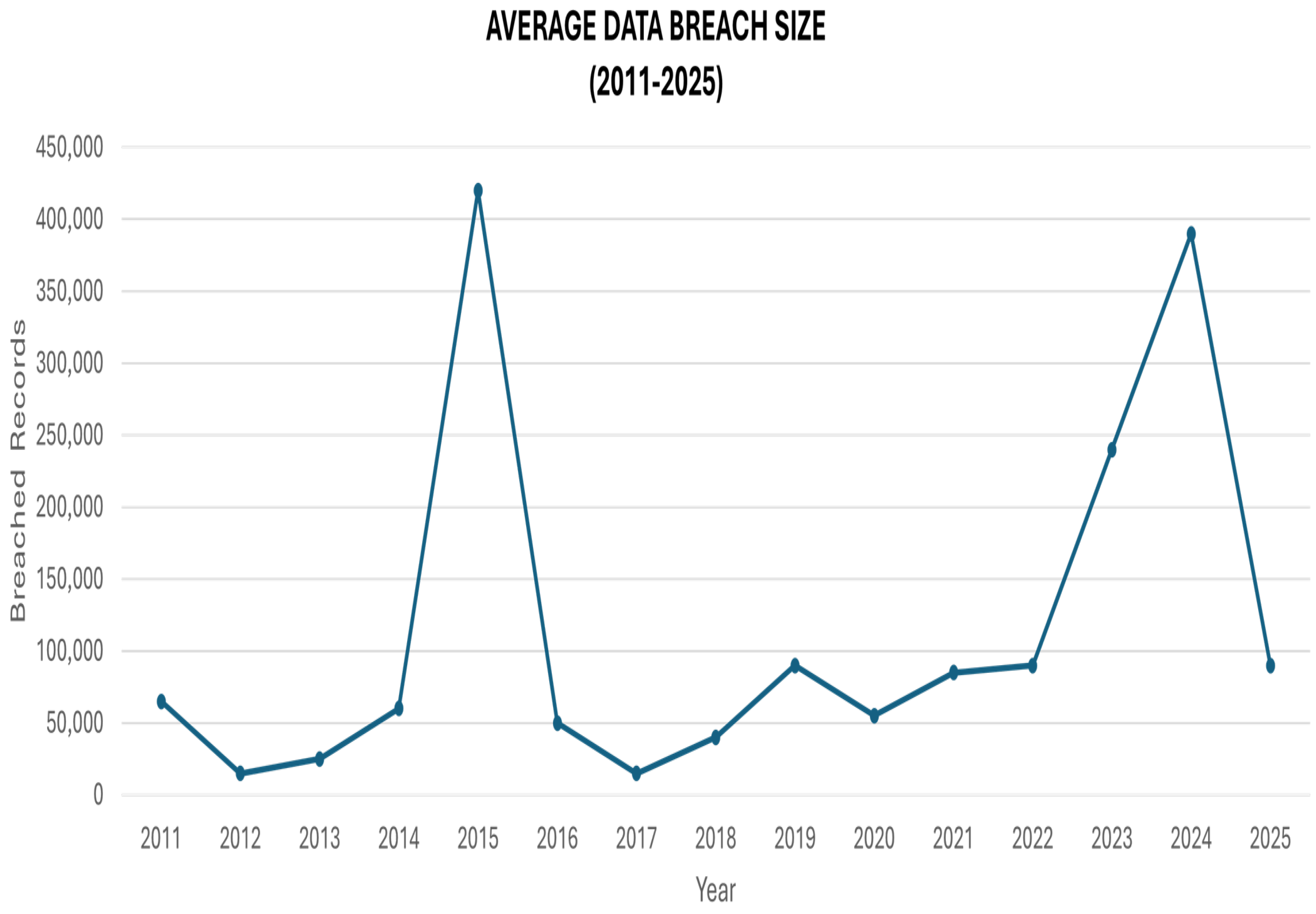

- Ransomware: Healthcare remains one of the most cyber attack-prone sectors due to its rapid digital transformation and increasing reliance on interconnected healthcare services. This shift has exposed significant security vulnerabilities that are increasingly exploited by cyber criminals, with ransomware emerging as one of the most severe and rapidly growing threats. Ransomware attacks have escalated in frequency and sophistication in recent years, causing substantial operational and financial disruptions to healthcare organizations. This study presents a comprehensive survey of ransomware attacks in healthcare and systematically categorizes existing mitigation and prevention strategies, including blockchain-based solutions, software-defined networking, machine learning techniques, and other security tools. It also highlights the key challenges faced by researchers in designing effective ransomware defenses for healthcare systems. Overall, the study offers valuable insights for researchers, healthcare institutions, and cyber security practitioners working to strengthen information security in healthcare environments.

- Man-In-The-Middle Attack: The healthcare sector is particularly vulnerable to man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks due to the rapid adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies in clinical environments. IoT-enabled healthcare applications, including electronic health records, telemedicine, telesurgery, mobile health, and remote patient monitoring, have significantly improved service delivery but have also expanded the attack surface. Modern hospitals deploy thousands of network-connected devices, averaging approximately 17 devices per hospital bed. Despite this growth, many medical IoT devices lack robust security mechanisms such as strong encryption and secure authentication [35].According to an industry analysis reported by Ordr [36], approximately 15–19% of IoMT devices deployed in healthcare environments continue to operate on Windows 7, an operating system that has reached end-of-life and no longer receives security updates. This estimate is derived from telemetry data collected across healthcare deployments primarily in North America and Europe, rather than a fully global sample. The continued use of unsupported operating systems significantly increases the attack surface of IoMT infrastructures, exposing medical devices to known vulnerabilities and facilitating cyberattacks such as ransomware, data breaches, and man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks. These risks are further exacerbated by resource-constrained medical sensors and insecure wireless communication protocols, making robust security mechanisms essential for ensuring data confidentiality, integrity, and availability in IoMT systems.In an IoMT environment, a man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack arises when an adversary successfully positions itself between medical sensors and a local processing unit (LPU), such as a smartphone, tablet, or gateway. This positioning is typically achieved by exploiting weaknesses in short-range wireless communication protocols, including Bluetooth Low Energy, in combination with the limited computational resources and security mechanisms available on medical sensors. As a result, the attacker gains unauthorized access to the communication channel without being detected by either endpoint [37]. After establishing this intermediary position, the attacker can passively monitor the exchanged physiological data, including parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation, thereby compromising patient confidentiality. More critically, the attacker may actively manipulate communication by modifying or replaying transmitted data. In emergency scenarios, abnormal physiological measurements can be replaced with previously recorded normal values before reaching the LPU, causing the monitoring system to incorrectly interpret the patient’s condition and suppress the generation of medical alerts.The threat is further amplified by the availability of off-the-shelf tools that enable the interception and manipulation of wireless traffic over distances exceeding the typical operating range of IoMT devices. Even when encryption is employed, flaws in device pairing, key establishment, and authentication procedures may allow attackers to decrypt messages or inject forged packets. Consequently, MitM attacks represent a severe risk in IoMT systems, as they compromise not only data privacy but also data integrity and the reliability of real-time clinical decision-making.

- SQL Injection: SQL injection is a significant cyber security threat to healthcare systems due to the extensive use of web-based applications such as electronic health records, patient portals, and billing platforms that rely on backend databases [38]. This attack occurs when malicious SQL code is inserted into input fields and executed by poorly secured applications, allowing attackers to access, modify, or delete sensitive data. In healthcare environments, successful SQL injection attacks can lead to unauthorized disclosure of protected health information, corruption of medical records, disruption of clinical services, and violations of regulatory requirements such as HIPAA [39]. The presence of legacy systems, inadequate input validation, and insufficient access controls further increases the susceptibility of healthcare organizations to such attacks. Consequently, mitigating SQL injection risks through secure coding practices, including parameterized queries, rigorous input validation, and regular security assessments, is essential to ensuring data integrity, patient safety, and trust in digital healthcare infrastructures.

Existing Mitigation Approaches for Outsider Threats

4.3. Blockchain Based Security Solutions

4.4. ML/DL Based Security Solutions

4.5. AI-Based Security Solutions

4.6. Cryptography Based Security Solutions

4.7. Research Gaps in Existing Literature

- Lack of real-world validation and cross-domain generalization: Most intrusion-detection or anomaly-detection frameworks are evaluated on synthetic or proprietary datasets. For example, a recent AI-driven IDS achieved high accuracy on NSL-KDD, but further tuning was needed to detect more complex attacks and operate with low latency. Others acknowledge that pilot deployments are required to test scalability and compliance in clinical settings. Real-world experiments, cross-institutional datasets, and longitudinal studies would strengthen evidence.

- Scalability and energy efficiency of blockchain-based solutions: Papers report strong security but also high computational overhead and transaction latency. Future work calls for optimizing consensus mechanisms and partitioning techniques to handle growing healthcare data volumes. Lightweight blockchains or off-chain strategies are needed to support resource-constrained medical devices without compromising security.

- Handling heterogeneous and complex threat landscapes: Many IDSs focus on DoS/grayhole attacks and assume homogeneous sensor networks. One study explicitly highlighted that improving detection rates for more complex intrusions and reducing latency should be targeted. Broader threat models (e.g., multi-vector attacks, insider threats, side-channel exploits) and datasets reflecting diverse IoT devices are required.

- Privacy-preserving analytics and decentralized identity management: Several approaches rely on centralized key authorities or share raw data among participants. The survey on blockchain-AI integration identified privacy-preserving techniques (differential privacy, secure multi-party computation) as an area for future research. Developing self-sovereign identity frameworks and integrating zero-knowledge proofs could minimize trust assumptions.

- Integration of quantum technologies: Quantum-based cryptography frameworks are proposed but remain largely conceptual and lack practical evaluation. Research should explore how quantum key distribution or quantum-secure algorithms can interoperate with existing healthcare blockchains and IoT devices.

- Explainability and regulatory compliance: High-accuracy deep-learning models often behave as black boxes. There is little discussion on explainable AI to support clinical decision-making or on how systems meet regulations such as HIPAA or GDPR. One review emphasizes the need for regulatory compliance to be addressed before widespread adoption of localhost. Future work should incorporate interpretable models and formal compliance checking.

- Dynamic trust management and user-centric design: Although some frameworks incorporate trust scores or fuzzy logic, they do not account for changing contexts, biases, or the needs of clinicians and patients. More research is needed on adaptive trust management, human-factor evaluations, and usability studies to ensure secure systems are acceptable in practice.

4.8. Vulnerabilities in Healthcare Systems

- Outdated medical devices with un-patched software: Healthcare environments rely heavily on legacy medical devices such as infusion pumps, imaging systems, and patient monitors that often run on outdated operating systems and firmware [76]. Many clinical devices, such as imaging systems, infusion pumps, patient monitors, and laboratory equipment, rely on legacy operating systems that cannot be easily updated due to vendor restrictions, certification requirements, or the risk of disrupting clinical operations. As a result, known vulnerabilities remain unaddressed for extended periods, making these devices attractive targets for cyber attacks. Un-patched systems are particularly susceptible to malware infections, ransomware, and network-based attacks [77], which can compromise device functionality, patient data confidentiality, and overall hospital operations. Furthermore, outdated devices often lack modern security mechanisms such as strong encryption, secure authentication, and intrusion detection capabilities [78]. Given their direct integration into clinical workflows, the exploitation of such vulnerabilities can have severe consequences, including service disruption, data breaches, and risks to patient safety. Addressing this issue requires coordinated efforts involving timely patch management, network segmentation, vendor accountability, and the gradual replacement of legacy medical devices with security-by-design alternatives.As a result, un-patched medical devices are commonly associated with ransomware infections, malware propagation, remote code execution, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, which can disrupt clinical operations and compromise patient safety.

- Network Mis-configurations: Network mis-configurations represent a critical vulnerability in healthcare systems, arising from improper setup of firewalls, access controls, segmentation policies, and communication protocols [79]. Common issues include overly permissive access rules, exposed services, default credentials, and insufficient network segmentation between clinical, administrative, and IoT device networks. Such weaknesses can enable attackers to move laterally within hospital networks, escalate privileges, and access sensitive patient data. Given the complexity and scale of healthcare IT infrastructures, mis-configurations are often unintentional [80] but can significantly increase the likelihood and impact of cyber incidents if not systematically identified and corrected. These weaknesses often enable man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks, lateral movement, privilege escalation, and data ex-filtration, allowing adversaries to intercept sensitive data or compromise multiple systems simultaneously.

- Default system credentials: The continued use of default or weak system credentials remains a critical security weakness in healthcare environments [81]. Many medical devices, network equipment, and healthcare applications are deployed with vendor-provided default usernames and passwords that are rarely changed due to operational oversight or usability concerns. Attackers commonly exploit these credentials through automated scanning and brute-force techniques to gain unauthorized access. Once compromised, default credentials can enable attackers to manipulate device functionality, access sensitive health data, or deploy malicious software [82]. Addressing this vulnerability requires enforcing strong authentication policies, mandatory credential changes, and the adoption of multi-factor authentication where feasible.This vulnerability is frequently linked to brute-force attacks, credential stuffing, unauthorized system access, and insider-assisted breaches, ultimately leading to data theft, system manipulation, or ransomware deployment.

- Insecure Firmware: Insecure firmware is a critical vulnerability in healthcare systems, as it operates at a low level and directly controls the behavior of medical devices, network equipment, and embedded systems [83]. When firmware is poorly designed, outdated, unsigned, or lacks integrity verification, attackers can exploit it to gain persistent and often undetectable access to devices. Compromised firmware is particularly dangerous in healthcare because it can survive system reboots and software updates, allowing long-term control over critical devices such as infusion pumps, imaging systems, patient monitors, and IoMT gateways.This vulnerability can enable several types of attacks. Firmware without secure boot or cryptographic signing can be modified to install backdoors, leading to advanced persistent threats (APTs) within hospital networks. Attackers may exploit insecure firmware update mechanisms to inject malicious code, resulting in device hijacking or malware propagation across connected systems [84]. In some cases, compromised firmware can be used to manipulate device behavior, causing data integrity attacks (e.g., falsifying patient readings) or denial-of-service (DoS) attacks that disrupt clinical operations. Additionally, insecure firmware may facilitate lateral movement, allowing attackers to pivot from a compromised medical device to other critical healthcare IT infrastructure [12].

- Unencrypted data storage or transmission: The absence of encryption for data at rest or in transit exposes sensitive healthcare information to unauthorized access and interception. Patient records, credentials, and operational data stored or transmitted in plain text can be easily captured by attackers monitoring network traffic or accessing compromised storage systems [85]. This vulnerability directly enables man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks, eavesdropping, and data leakage, and can also support identity theft and credential harvesting. In clinical systems, unencrypted communications between devices and servers may further allow attackers to alter or inject data, leading to data tampering and potential disruption of medical decision-making processes.

- Legacy systems lacking modern security controls: Legacy healthcare systems often operate on outdated platforms that lack contemporary security mechanisms such as strong encryption, fine-grained access control, continuous monitoring, and compatibility with modern authentication protocols [86]. These systems are frequently retained due to high replacement costs, regulatory constraints, or dependence on specialized clinical workflows. However, their limited security capabilities make them attractive targets for cyber adversaries. The absence of modern protections increases susceptibility to ransomware attacks, where attackers exploit known weaknesses to encrypt critical clinical data and disrupt healthcare operations [87]. Legacy systems are also vulnerable to unauthorized access and privilege escalation attacks, as they often lack support for multi-factor authentication and robust logging mechanisms [88]. Additionally, outdated protocols and unsupported software components can enable man-in-the-middle attacks, allowing adversaries to intercept or manipulate sensitive healthcare data during transmission. As healthcare infrastructures continue to integrate digital services, the continued reliance on legacy systems significantly amplifies the overall cyber risk profile of healthcare organizations [53].

5. Internet of Things (IoMT) Medical Devices and Equipment

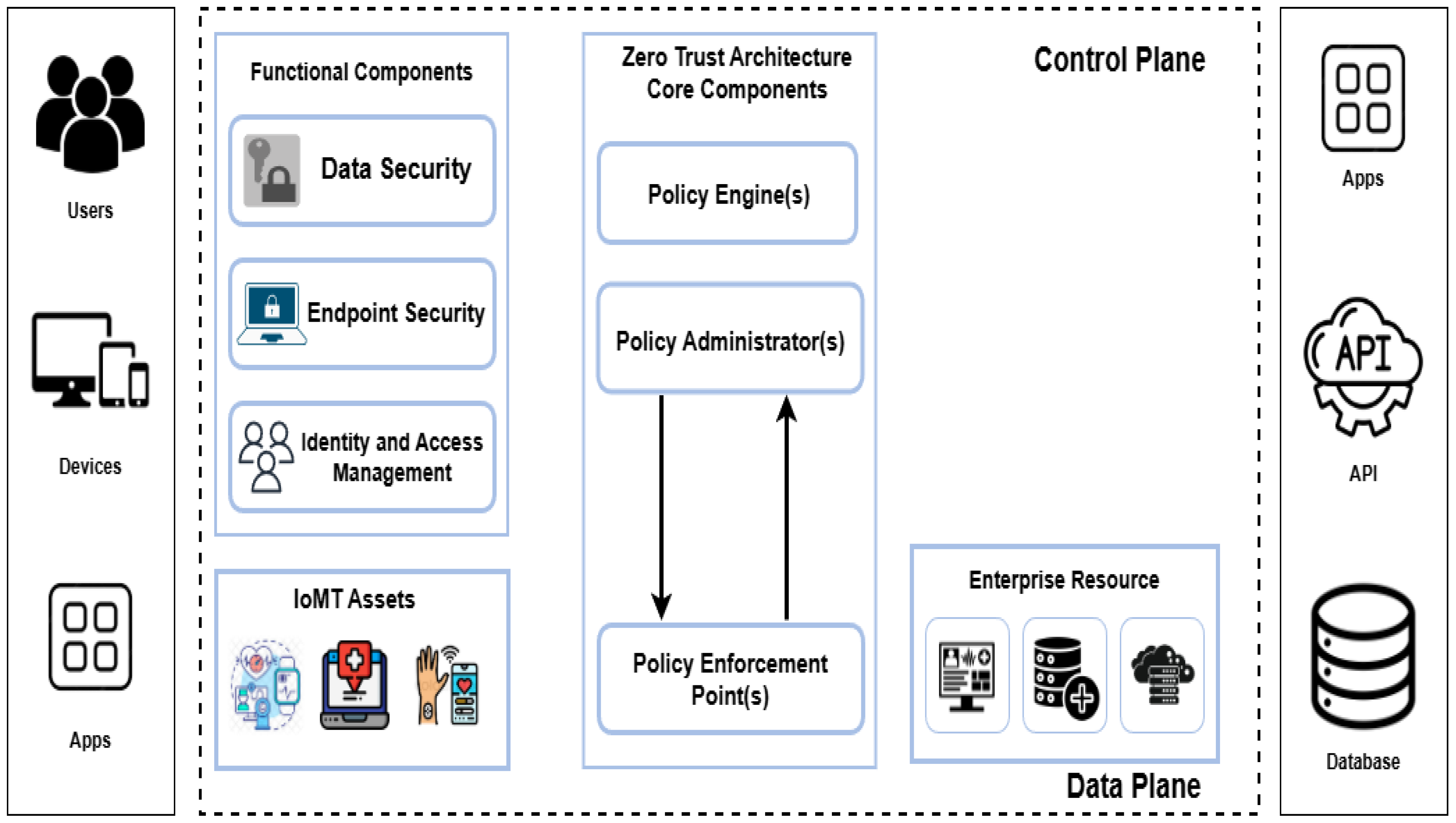

5.1. Zero-Trust Brokerage Between IoMT Devices and EHR Systems

5.2. Research Gaps and Open Challenges in IoMT Cyber Security

- 1.

- Resource Constraints and Lightweight Security: One of the fundamental challenges in IoMT security is the severe resource limitation of medical devices, including constrained processing power, memory, and battery life. Many conventional cryptographic and intrusion detection mechanisms designed for traditional IT systems are unsuitable for implantable or wearable medical devices [30]. Although lightweight cryptographic schemes have been proposed, there is still a lack of standardized, clinically validated solutions that balance security, energy efficiency, and real-time responsiveness.

- 2.

- Security versus Safety Trade-offs: A critical research gap lies in the interaction between cyber security and patient safety. Security mechanisms such as frequent authentication, encryption, or firmware updates may introduce latency or operational disruptions that are unacceptable in life-critical medical applications. Current literature often treats security and safety as separate concerns, whereas IoMT systems require integrated frameworks that explicitly model and manage their inter-dependencies [92]. Establishing formal methods to evaluate the safety impact of security controls remains an open challenge.

- 3.

- Lack of Real-World Validation and Deployment Studies: Most existing IoMT security solutions are evaluated through simulations or small-scale testbeds. There is a notable lack of real-world deployment studies demonstrating long-term effectiveness, usability, and resilience in clinical environments [90]. Healthcare organizations operate under strict regulatory, operational, and financial constraints, which are often overlooked in academic research. Bridging the gap between laboratory research and hospital-scale implementation is essential.

- 4.

- Heterogeneity and Interoperability Challenges: IoMT ecosystems are inherently heterogeneous, comprising devices from multiple vendors, legacy medical equipment, diverse communication protocols, and cloud services. This heterogeneity complicates the enforcement of uniform security policies and consistent patch management [30]. Interoperability requirements often force security compromises, creating weak links that attackers can exploit. Future research must address secure interoperability without sacrificing compatibility or clinical usability.

- 5.

- Limited Incident Reporting and Threat Intelligence Sharing: Another major gap is the lack of transparent incident reporting and shared threat intelligence in the healthcare sector. Cyber incidents involving medical devices are often under-reported due to reputational concerns and regulatory implications [90]. This limits the availability of real-world attack data, hindering the development of accurate threat models and evidence-based defense mechanisms.

- 6.

- Regulatory and Compliance Challenges: While regulatory bodies such as the FDA and European MDR emphasize cyber security, regulations often lag behind rapidly evolving threats. Existing standards provide high-level guidance but lack detailed technical specifications for secure-by-design IoMT systems [92]. Moreover, global variations in regulatory requirements complicate cross-border IoMT deployments and data sharing, highlighting the need for harmonized cyber security standards.

- 7.

- Emerging Threats and Future Technologies: The increasing integration of AI, cloud computing, and edge intelligence into IoMT introduces new attack vectors, including data poisoning, model inversion, and adversarial learning attacks. Current IoMT security literature provides limited coverage of these emerging threats [92]. As healthcare systems move toward data-driven and autonomous decision-making, securing both data and learning processes becomes a critical research priority.

- 8.

- Need for Proactive and Adaptive Security Frameworks: Most existing approaches focus on reactive defenses, such as detecting known attacks or patching vulnerabilities after discovery. There is a growing need for proactive, adaptive, and risk-aware security frameworks capable of anticipating threats and responding dynamically to changing attack surfaces [91]. Incorporating continuous monitoring, threat intelligence, and adaptive defense mechanisms remains an open research challenge.

6. Impact of Cyber Threats on Patient Safety and Operations

7. Data Privacy Challenges in Healthcare

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, J.; Hu, G. Twenty-five years of evolution and hurdles in electronic health records and interoperability in medical research: Comprehensive review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eappen, P.; Vajjhala, N.R. (Eds.) Healthcare Informatics Innovation Post COVID-19 Pandemic, 1st ed.; Auerbach Publications (Taylor & Francis): New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbodo, D.C.; Awan, I.-U.; Cullen, A.; Zahrah, F. From Regulation to Reality: A Framework to Bridge the Gap in Digital Health Data Protection. Electronics 2025, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, A.Y. Strengthening compliance with data privacy regulations in US healthcare cybersecurity. Asian J. Res. Comput. Sci. 2025, 18, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-K.; Zeng, N.-C.; Zhang, D.-M.; Argyroudis, S.; Mitoulis, S.-A. Resilience models for tunnels recovery after earthquakes. Engineering 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoisi, S.E.; Ottah, I.O. Data security, confidentiality in healthcare management in Nigeria: Need for compliance with health information law. Med. Health Sci. Eur. J. 2025, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ewoh, P.; Vartiainen, T. Vulnerability to cyberattacks and sociotechnical solutions for health care systems: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, M.R. Cybercrime and other threats faced by the healthcare industry. Trend Micro 2017, 5566. Available online: http://sitemaps.b51.nl/sites/default/files/pdf/wp-cybercrime-%26-other-threats-faced-by-the-healthcare-industry.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, I.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Saha, R. Cybersecurity Challenges in IT Infrastructure and Data Management: A Comprehensive Review of Threats, Mitigation Strategies and Future Trend. Glob. Mainstream J. Innov. Eng. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 1, 36–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwo, O.J.; Adesokan-Imran, T.O.; Babarinde, D.C.; Oyekunle, S.M.; Olutimehin, A.T.; Olaniyi, O.O. Advancing security in cloud-based patient information systems with quantum-resistant encryption for healthcare data. Asian J. Res. Comput. Sci. 2025, 18, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbe, N.; Almalki, M. IoT-enabled healthcare transformation leveraging deep learning for advanced patient monitoring and diagnosis. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 21331–21344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuya, R.; Liu, X. Policy and management implications of firmware vulnerabilities in medical IoT devices: A multi-case analysis. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alserhani, F. Intrusion Detection and Real-Time Adaptive Security in Medical IoT Using a Cyber-Physical System Design. Sensors 2025, 25, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snigdha, E.Z.; Jalil, M.S.; Dahwal, F.M.; Saeed, M.; Mehedy, M.T.J.; Hasan, S.K.; Al Mamun, A.; Khan, M.D.N. Cybersecurity in Healthcare IT Systems: Business Risk Management and Data Privacy Strategies. Am. J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 7, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, D.; Budaragade, A.P.; Salunkhe, U.; Gurav, U.P.; Patil, A. Internet of Medical Things: Architecture, Trends, Challenges and the Evolution Towards IoMT 5.0. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2025, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeanyim, O.C.; Nwabunwanne, E.C.; Igbokwe, N.C.; Nwamekwe, C.O. Patient Flow and Service Efficiency in Public Hospitals. J. Health Indones. 2025, 3, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, Z.; Abdelgawad, A.; Elsayed, N. Cybersecurity and Frequent Cyber Attacks on IoT Devices in Healthcare: Issues and Solutions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.11250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, A. Addressing Challenges in Cybersecurity Implementation Across Diverse Industrial and Organizational Sectors. SSRN 2025, SSRN 5268082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, P.; Vlahu-Gjorgievska, E.; Chow, Y.-W. Security and privacy of technologies in health information systems: A systematic literature review. Computers 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarkas, O.; Ko, R.; Dong, N.; Mahmud, R. A Container Security Survey: Exploits, Attacks and Defenses. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, B. Cybersecurity in Healthcare: New Threat to Patient Safety. Cureus 2025, 17, e83614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erukayenure, O.; Bashir, H.A.; Adekunbi, A.; Abere, S.E.; Okpan, O.; Guwa, A.A. Human factor vulnerabilities in healthcare cybersecurity: Mitigating insider threats in medical facilities. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 17, 024–031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, S. A Lightweight AI Model for Detecting Insider Threats in Hospital Networks. Res. Prepr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.D.D. Advanced Privacy-Preserving Decentralized Federated Learning for Insider Threat Detection in Collaborative Healthcare Institutions. Ph.D. Thesis, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I. Analysis of insider threats in the healthcare industry: A text mining approach. Information 2022, 13, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, N.; Hasan, M.N.; Koo, I. Few-Shot Transfer Learning-Based Fault Classification in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 55017–55033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagala, L.P.; Hossain, G. Analyzing insider threats and human factors in healthcare 5.0. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life Using AI, Robotics and IoT (HONET), Boca Raton, FL, USA, 4–6 December 2023; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Deep, G.; Sidhu, J.; Mohana, R. Insider threat prevention in distributed database as a service cloud environment. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.A.; Lakhan, A.; Zebari, D.A.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Nedoma, J.; Martinek, R.; Tariq, U.; Alhaisoni, M.; Tiwari, P. Adaptive secure malware efficient machine learning algorithm for healthcare data. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, M.; Karageorgou, M.; Mantas, G.; Sucasas, V.; Essop, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Lymberopoulos, D. A survey on security threats and countermeasures in internet of medical things (IoMT). Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, K.S.; Nenova, M.; Iliev, G. A study of cyber attacks: In the healthcare sector. In Proceedings of the 2021 Sixth Junior Conference on Lighting, Gabrovo, Bulgaria, 23–25 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.; Mishra, K.N.; Dutta, S. Detection and prevention of DDoS attacks on M-healthcare sensitive data: A novel approach. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2022, 14, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, N.; Jan, S.U.; Hasan, M.N.; Koo, I. A Hybrid LATAM and Few-Shot Learning Framework for Fault Diagnosis in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 43102–43116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, A.K.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Ganesh, A.; Kiruthiga, T. Emerging cyber security and brute force attacks in hospital management information systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second International Conference on Smart Technologies for Smart Nation (SmartTechCon), Singapore, 18–19 August 2023; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Verizon Business. How to Prevent Man-in-the-Middle Attacks in Healthcare. Available online: https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/articles/s/how-to-prevent-man-in-the-middle-attacks-in-healthcare/ (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- ORDR. Rise of the Machines Report 2024. ORDR 2024. Available online: https://ordr.net/resources/rise-of-the-machines-report-2024 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Salem, O.; Alsubhi, K.; Shaafi, A.; Gheryani, M.; Mehaoua, A.; Boutaba, R. Man-in-the-middle attack mitigation in Internet of Medical Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, M.M.; Aldaghmi, N.; Aljuaid, H. IoT Security in Healthcare: A Recent Trend and Predictive Study of SQL Injection Attacks. J. Eng. 2025, 2025, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrin, T. Managing HIPAA compliance includes legal and ethical considerations. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaranathan, S.; Geetha, R. Deep learning enabled blockchain based electronic heathcare data attack detection for smart health systems. Meas. Sens. 2024, 31, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiofor, O.; Akinsola, A. Securing the future of healthcare: Building a resilient defense system for patient data protection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.16170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, A.; Rao, B.S.; Akthar, N.; Rafi, S.M.; Singh, P.; Das, S.; Manikandan, G. A novel algorithm to secure data in new generation health care system from cyber attacks using iot. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. (IJEER) 2022, 10, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamoli, A.; Kirsali, A.; Sharma, S. Cyber Attack Prevention Method for Enhanced Privacy of Patients Digital Healthcare Data in Smart Hospitals. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT), Kollam, India, 8–9 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Akinade, S.K. Implementing AI-driven anomaly detection for cyber-security in healthcare networks. ATBU J. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2024, 12, 598–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kilincer, I.F.; Ertam, F.; Sengur, A.; Tan, R.-S.; Acharya, U.R. Automated detection of cybersecurity attacks in healthcare systems with recursive feature elimination and multilayer perceptron optimization. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 43, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünözkan, H.; Ertem, M.; Bendak, S. Using attack graphs to defend healthcare systems from cyberattacks: A longitudinal empirical study. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2022, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ul Sami, I.; Ahmad, M.B.; Asif, M.; Ullah, R. DoS/DDoS detection for E-Healthcare in internet of things. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Minocha, S.; Joshi, K.; Sharma, A.; Namasudra, S. Research challenges and future work directions in smart healthcare using IoT and machine learning. Adv. Comput. 2025, 137, 353–381. [Google Scholar]

- Premchand, P.; Lakshmi, M.V.; Zameer, S.R.; Rao, V.S.; Krishna, K.G. The SQL Injection Uses Malicious Code to Manipulate Your Database into Revealing Information. Fuzzy Syst. Soft Comput. 2025, 16, 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, C. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and Encryption Techniques for Enhancing Relational Database Security. Res. Prepr. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392346447_ROLE-BASED_ACCESS_CONTROL_RBAC_AND_ENCRYPTION_TECHNIQUES_FOR_ENHANCING_RELATIONAL_DATABASE_SECURITY (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Piskachev, G. Adapting Taint Analyses for Detecting Security Vulnerabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paderborn, Paderborn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, S.S. Securing against advanced cyber threats: A comprehensive guide to phishing, XSS and SQL injection defense. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 6, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, A.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Sallos, M.P.; Martinez-Caro, E.; Chinnaswamy, A. Resilience in healthcare systems: Cyber security and digital transformation. Technovation 2023, 121, 102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulatif, A.; Khalil, I.; Saidur Rahman, M. Security of blockchain and AI-empowered smart healthcare: Application-based analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapaaking, A.P.; Khalil, I.; Yi, X. Blockchain-based federated learning with SMPC model verification against poisoning attack for healthcare systems. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2023, 12, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfakeeh, A.S. A blockchain-enabled IoT framework for secure attack detection and advanced feature selection in smart healthcare. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 28219–28223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamro, H.; Marzouk, R.; Alruwais, N.; Negm, N.; Aljameel, S.S.; Khalid, M.; Alsaid, M.I. Modeling of blockchain assisted intrusion detection on IoT healthcare system using ant lion optimizer with hybrid deep learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 82199–82207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, R.; Gupta, G.P.; Islam, A.N.; Shorfuzzaman, M. Permissioned blockchain and deep learning for secure and efficient data sharing in industrial healthcare systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 8065–8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Tariq, N.; Ashraf, M.; Khan, F.A.; Asim, M.; Imran, M. Securing smart healthcare cyber-physical systems against blackhole and greyhole attacks using a blockchain-enabled gini index framework. Sensors 2023, 23, 9372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshay Kumaar, M.; Samiayya, D.; Vincent, P.D.R.; Srinivasan, K.; Chang, C.Y.; Ganesh, H. A hybrid framework for intrusion detection in healthcare systems using deep learning. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 824898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thilagam, K.; Beno, A.; Lakshmi, M.V.; Wilfred, C.B.; George, S.M.; Karthikeyan, M.; Karunakaran, P. Secure IoT healthcare architecture with deep learning-based access control system. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 2638613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengan, S.; Khalaf, O.I.; Sharma, D.K.; Hamad, A.A. Secured and privacy-based IDS for healthcare systems on e-medical data using machine learning approach. Int. J. Reliab. Qual. E-Healthc. 2022, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ali, H.; Saeed, A.; Ahmed Khan, A.; Tin, T.T.; Assam, M.; Mohamed, H.G. Blockchain-powered healthcare systems: Enhancing scalability and security with hybrid deep learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Pasha, M.F.; Ali, J.; Fang, O.H.; Masud, M.; Jurcut, A.D.; Alzain, M.A. Deep learning based homomorphic secure searchable encryption for keyword search in blockchain healthcare system: A novel approach to cryptography. Sensors 2022, 22, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Otaibi, S.; Ayouni, S.; Sarwar, N.; Irshad, A.; Ullah, F. AI-driven security framework for medical sensor networks: Enhancing privacy and trust in smart healthcare systems. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, W.; Martinez, E.; Hernandez, D.; Lopez, B.; Gonzalez, R.; Wilson, S.; Anderson, J. A Hybrid AI Framework for Detecting Insider Threats in Hospital Information Systems. ResearchGate 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Olatunji-Isreal/publication/398453610_A_Hybrid_AI_Framework_for_Detecting_Insider_Threats_in_Hospital_Information_Systems/links/693708f706a9ab54f8450fde/A-Hybrid-AI-Framework-for-Detecting-Insider-Threats-in-Hospital-Information-Systems.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Bonagiri, K.; Nici Marx, V.S.; Gopalsamy, M.; Iyswariya, A.; Reni Hena Helan, R.; Sultanuddin, S.J. AI-driven healthcare cyber-security: Protecting patient data and medical devices. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Intelligent Cyber Physical Systems and Internet of Things (ICoICI), Coimbatore, India, 28–30 August 2024; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Moparthi, N.R.; Namasudra, S.; Shanmuganathan, V.; Hsu, C.H. Blockchain-based IoT architecture to secure healthcare system using identity-based encryption. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhiri, S.; Egio, A.; Compastié, M.; Cosio, P. Proxy re-encryption for enhanced data security in healthcare: A practical implementation. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna, Austria, 30 July–2 August 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Saxena, D.; Rani, P.; Kumar, J.; Makkar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Lee, C.N. An intelligent quantum cyber-security framework for healthcare data management. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 6884–6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Bansal, A.; Gupta, D.; Juneja, S.; Turabieh, H.; Elarabawy, M.M.; Bitsue, Z.K. Using identity-based cryptography as a foundation for an effective and secure cloud model for e-health. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 7016554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.M.; Kumar, R.M.S. Efficient lightweight cryptographic solutions for enhancing data security in healthcare systems based on IoT. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1522184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kore, A.; Patil, S. Cross-layered cryptography based secure routing for IoT-enabled smart healthcare system. Wirel. Netw. 2022, 28, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TechMagic. Cyber-Attacks in Healthcare: Types, Risks, and Prevention Strategies. TechMagic Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.techmagic.co/blog/cyber-attacks-in-healthcare (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- HIPAA Journal. Healthcare Data Breach Statistics. HIPAA J. 2026. Available online: https://www.hipaajournal.com/healthcare-data-breach-statistics/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Ogunseye, O. Securing the Future of Healthcare: Addressing Cybersecurity Risks in Legacy Medical IoT Devices. Master’s Thesis, Bowie State University, Bowie, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R.; Ridder, E. Healthcare Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cybersecurity and Cybercrime, Boston, MA, USA, 16–18 November 2022; Volume 9, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz, N.; Banoori, F.; Koo, I. Reshaping bioacoustics event detection: Leveraging few-shot learning (FSL) with transductive inference and data augmentation. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Papastergiou, S.; Kalogeraki, E.-M.; Kioskli, K. Cyberattack path generation and prioritisation for securing healthcare systems. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, H.; Kwon, J.; Im, G. Taming complexity in the cybersecurity of multihospital systems: The role of enterprise-wide data analytics platforms. MIS Q. 2025, 49, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleski, T.; Ahmed, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, E. A review of multi-factor authentication in the Internet of Healthcare Things. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231177144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Ghazal, T.M.; Saeed, R.A.; Pandey, B.; Gohel, H.; Eshmawi, A.A.; Abdel-Khalek, S.; Alkhassawneh, H.M. A review on security threats, vulnerabilities, and counter measures of 5G enabled Internet-of-Medical-Things. IET Commun. 2022, 16, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Haq, S.; Singh, Y.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, R.; Gupta, D. A survey on IoT and embedded device firmware security: Architecture, extraction techniques, and vulnerability analysis frameworks. Discov. Internet Things 2023, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Saeed, U.; Koo, I. Robust sensor fault detection in wireless sensor networks using a hybrid conditional generative adversarial networks and convolutional autoencoder. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 13912–13926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunoori, V. A Comprehensive Review of Encryption and Protection Techniques for Healthcare Data. In Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Information Systems—Security and Privacy Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Xu, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Bao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, H. A review of security issues and solutions for precision health in Internet-of-Medical-Things systems. Secur. Saf. 2023, 2, 2022010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Saeed, U.; Koo, I. FedLSTM: A federated learning framework for sensor fault detection in wireless sensor networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, W. Modernization framework to enhance the security of legacy information systems. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2022, 32, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, A.I.; Sikder, A.K.; Rahman, M.A.; Uluagac, A.S. A survey on security and privacy issues in modern healthcare systems: Attacks and defenses. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 2021, 2, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaw, S.T.; Troncoso-Pastoriza, J.R.; Lacey, D.; Florin, M.-V.; Calcavecchia, F.; Anderson, D.; Burleson, W.; Vogel, J.M.; O’Leary, C.; Eshaya-Chauvin, B.; et al. Cybersecurity of Hospitals: Discussing the Challenges and Working Towards Mitigating the Risks. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.S.; Sagayarajan, S.; Baskar, D.T.; George, A.S.H. Extending Detection and Response: How MXDR Evolves Cybersecurity. Partners Univers. Int. Innov. J. 2024, 2, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Lupu, E.; Drakakis, E.M.M.; Bharath, A.A.; Leung, Z.K.; Ma, G.R.; Chattopadhyay, A. Securing the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): Real-World Attack Taxonomy and Practical Security Measures. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.19609. [Google Scholar]

- Obrik-Uloho, E.P.; Ejiofor, V.O.; Egonwanne, C.H.; Kolo, F.H.O.; Olasege, R.O. Zero-trust architecture for smart hospitals: A virtual blueprint for cyber-resilient healthcare infrastructure. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2025, 25, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topflight Apps. Zero-Trust Architecture in Healthcare: Why It Matters and How It Works. Topflight Apps Blog. 2024. Available online: https://topflightapps.com/ideas/zero-trust-architecture-healthcare/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- FedTech Magazine. Zero trust stands as a secure foundation for the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). FedTech Magazine, 21 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shammar, E.; Cui, X.; Zahary, A.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Al-qaness, M.A.A. Threat to trust: A systematic review on Internet of Medical Things security. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2025, 206, 105172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, I.; Odeh, A. Security and privacy of electronic health records: Concerns and challenges. Egypt. Inform. J. 2021, 22, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, S.L.; Sharma, J.B. Medical oversight and public trust of medicine: Breaches of trust. In The Complex Role of Patient Trust in Oncology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report. IBM Security Report. 2024. Available online: https://cdn.table.media/assets/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/30132828/Cost-of-a-Data-Breach-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Basil, N.N.; Ambe, S.; Ekhator, C.; Fonkem, E.; Nduma, B.N. Health records database and inherent security concerns: A review of the literature. Cureus 2022, 14, e30168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitta, S.; Crawly, J.; Reddy, S.G.; Kumar, D. Balancing data sharing and patient privacy in interoperable health systems. Distrib. Learn. Broad Appl. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 886–925. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, J.; Jahankhani, H.; Kendzierskyj, S. Cyber-Physical Attacks and the Value of Healthcare Data: Facing an Era of Cyber Extortion and Organised Crime. In Blockchain and Clinical Trial: Securing Patient Data; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, A.E.; Omolayo, O.; Aduloju, T.D.; Okare, B.P.; Oyasiji, O.; Okesiji, A. Human-centered privacy protection frameworks for cyber governance in financial and health analytics platforms. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2021, 2, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.L.; Pérez, M.G.; Ruiz-Martínez, A. A comprehensive model for securing sensitive patient data in a clinical scenario. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 137083–137098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, K.; Simon, D.A.; Lucassen, A. Patient data ownership: Who owns your health? J. Law Biosci. 2021, 8, lsab023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwej, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Kulshrestha, N.; Mishra, P. A methodical analysis of medical internet of things (MIoT) security and privacy in current and future trends. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2022, 9, d346–d371. [Google Scholar]

- Jaime, F.J.; Muñoz, A.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.; Jerez-Calero, A. Strengthening privacy and data security in biomedical microelectromechanical systems by IoT communication security and protection in smart healthcare. Sensors 2023, 23, 8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, E.S.N.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Rao, N.T. Managing information security risk and Internet of Things (IoT) impact on challenges of medicinal problems with complex settings: A complete systematic approach. In Multi-Chaos, Fractal and Multi-Fractional Artificial Intelligence of Different Complex Systems; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, K.; Venkatesh, R.; Venkatesh, P. A Review on Smart Healthcare Employing Quantum Internet of Things. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2025, 53, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xie, L.; Zhang, D.; Lei, X.; Xu, F.; Liu, Z. Shardora: Towards Scaling Blockchain Sharding via Unleashing Parallelism. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2024, 2024/1896. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Namasudra, S.; Chilamkurti, N.; Kim, B.-G.; Gonzalez Crespo, R. Blockchain-based privacy preservation for IoT-enabled healthcare system. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2023, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Y.; Ma, L.; Du, S.; Zhu, H.; Pei, Q.; Shen, X. A Federated Learning Based Privacy-Preserving Smart Healthcare System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Ning, Z.; Zhu, B. Privacy-preserved electronic medical record exchanging and sharing: A blockchain-based smart healthcare system. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 26, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padinjappurathu Gopalan, S.; Chowdhary, C.L.; Iwendi, C.; Farid, M.A.; Ramasamy, L.K. An efficient and privacy-preserving scheme for disease prediction in modern healthcare systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayub, M.S.; Saadi, M.; Koo, I. Optimization of RIS-Assisted 6G NTN Architectures for High-Mobility UAV Communication Scenarios. Drones 2025, 9, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ransomware Family | Initial Compromise Vector | Payload Execution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| WannaCry | Exploitation of un-patched SMB services (EternalBlue vulnerability) | Executes the ransomware payload by encrypting local files using embedded cryptographic routines after successful exploitation, followed by optional self-propagation via SMB scanning. |

| Locky | Phishing emails containing malicious document attachments | Embedded macros or scripts download and execute the ransomware binary on compromised hosts. |

| SamSam | Unauthorized access via weak RDP credentials or vulnerable web services | Performs privilege escalation and manually encrypts systems across the network using customized tools. |

| Ryuk | Phishing-based malware delivery through infected email attachments | Uses PowerShell or script-based loaders to deploy ransomware and enable lateral movement. |

| Maze | Social engineering via phishing emails carrying malicious files | Downloads the payload, encrypts local and shared files, and threatens public disclosure of stolen data. |

| Petya/NotPetya | Combination of SMB exploitation and phishing campaigns | Harvests credentials, leverages native tools (e.g., PsExec), and disrupts system boot processes. |

| Cerber | Email-based phishing attacks and exploit kits | Deploys ransomware via scripts or macros and communicates with distributed command-and-control servers. |

| Ref | Problem Focus | Proposed Approach | Attacks/Threats | Data/Evaluation Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Protecting smart-health and personal medical device (PMD) data integrity | Blockchain-enabled framework integrating IPFS, FHIR APIs, and a GAN-based intrusion detection system for monitoring PMD communication | DoS, replay attacks, man-in-the-middle (MitM), false data injection | Approximately 98.7% detection accuracy with an F1-score close to 98% across multiple attack scenarios |

| [41] | Cyberattack detection in healthcare cyber-physical systems (HCPSs) | Cognitive machine learning assisted attack detection framework (CML-ADF) supporting secure data sharing and intelligent threat prediction | DoS, sniffing, routing attacks, impersonation, code injection | Achieves 98.2% accuracy and a 96.5% attack prediction rate with reduced communication overhead |

| [42] | Availability protection for mobile healthcare (m-health) cloud systems | Novel DDoS detection and prevention algorithm evaluated in a cloud-based simulation environment | Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks | Simulation results demonstrate effective DDoS detection and mitigation |

| [43] | Privacy preservation of patient data in smart hospitals | Cyberattack prevention framework employing two-factor authentication (OTP and CAPTCHA), encrypted credentials, and role-based access control | Unauthorized access, credential compromise, spamming | Design-oriented evaluation emphasizing enhanced privacy and access control mechanisms |

| [44] | Secure storage and transmission of healthcare data during large-scale digitization | Cryptography-based data protection approach using AES, DES, 3DES, and RSA algorithms | General cyber threats against digital healthcare data | Conceptual analysis and comparison of cryptographic techniques without experimental benchmarking |

| [32] | Prediction and mitigation of healthcare data breach risks | Gradient boosting—a predictive model for assessing the severity of healthcare data breaches | Hacking incidents, network/server breaches, IT-related attacks | Evaluated using datasets from the US Department of Health and Human Services and Kaggle, demonstrating strong predictive performance |

| Ref & Year | Methods | Techniques | Problem Focus | Network Model | Dataset | Evaluation Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] (2023) | Blockchain-based IDS | GAN, blockchain | PMD attack detection | Smart PMD IoT network | Simulated PMD traffic | Accuracy >98% | High detection accuracy | Evaluated only on simulated data |

| [55] (2023) | Blockchain-secured IDS | CNN | Intrusion detection | IoT healthcare network | OCTMNIST, TissueMNIST | Accuracy, precision | Data privacy | High computational costs and energy resources |

| [68] (2021) | Blockchain-based authentication | IBS, AES, blockchain | Secure IoT authentication | IoT healthcare sensors | Hospital records | Qualitative analysis (scalability, integrity, and access control) | Strong access control | Relies on trusted authority |

| [57] (2022) | Blockchain-based IDS | ALO, CNN-LSTM | Intrusion detection | IoT healthcare | Simulated IoT data | Accuracy, F1-score | High IDS performance | Lacks real deployment |

| [58] (2022) | Permissioned blockchain | SNNA, RBM | Secure data sharing | Industrial healthcare | Proprietary data | Accuracy, FPR | Efficient data validation | Scalability not tested |

| [59] (2023) | Blockchain-based routing security | Gini index, blockchain | Grayhole attacks | Healthcare CPS routing | Simulated routing | PLR, delay, energy | Improved routing metrics | Blockchain overhead |

| [67] (2024) | Deep-learning IDS | CNN/LSTM, ECC | Intrusion detection and authentication | IoT medical sensors | NSL-KDD | Accuracy , | High accuracy | Benchmark-limited |

| [70] (2025) | Quantum security | Quantum encryption | Secure data management | Distributed hospitals | Hospital records | Accuracy up to 3.13–16.13% (maximum improvement) | Improved confidentiality | High complexity; no blockchain |

| [72] (2025) | Lightweight chaotic-map encryption | Chaos theory, logistic map | Medical image security | Stand-alone system | Medical images | NPCR , UACI | Strong diffusion | Encryption-only; no IDS |

| [66] (2024) | Hybrid AI | ML/DL, encryption | Cyber-threat detection | IoT healthcare | Simulated log | not specified | Adaptive detection | Simulated data |

| [40] (2024) | Deep learning and blockchain-based | GAN, ANN, SVM, and KNN | Integrity attack detection | Smart health system | PMD communication traffic dataset | Accuracy >98%, % | High detection accuracy | Limited to four attacks |

| Threat Category | Threat Type | Description | Insider/Outsider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malware Attacks | Ransomware | Encrypt clinical and administrative data to extort ransom, often disrupting hospital operations and patient care | Outsider |

| Malware Attacks | Spyware/Trojan | Covertly gather sensitive patient or credential data for unauthorized access or illicit use | Outsider |

| Network-Based Attacks | Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) | Intercept communications between medical devices, clinicians, and servers, enabling data manipulation or theft | Outsider |

| Network-Based Attacks | Denial-of-Service (DoS/DDoS) | Flood healthcare networks or services, causing downtime and delaying clinical services | Outsider |

| Credential-Based Attacks | Brute Force Attacks | Attempt repeated username–password combinations to gain unauthorized system access | Outsider |

| Credential-Based Attacks | Credential Theft | Use phishing or malware to obtain healthcare staff credentials, enabling unauthorized access | Insider/Outsider |

| Insider Threats | Malicious Insider | Authorized personnel deliberately misuse access to steal, alter, or disclose sensitive patient data | Insider |

| Insider Threats | Negligent Insider | Unintentional exposure of data due to poor security practices or policy violations | Insider |

| System Vulnerabilities | Exploitation of Legacy Systems | Target outdated healthcare systems lacking modern security controls or timely patches | Outsider |

| Cloud and Data Threats | Data Leakage | Unauthorized disclosure of EHRs due to misconfigurations or weak access control mechanisms | Insider/Outsider |

| Healthcare Vulnerability | Associated Attack Types | MITRE ATT&CK Tactics | Healthcare Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outdated medical devices with unpatched software | Ransomware, malware injection, remote code execution | Initial Access, Execution, Persistence | Legacy infusion pumps and imaging systems running outdated operating systems have been exploited during ransomware campaigns such as WannaCry, causing service disruption in hospitals |

| Network misconfigurations | Man-in-the-middle attacks, lateral movement, data exfiltration | Lateral Movement, Credential Access, Collection | Improperly segmented hospital networks allow attackers to pivot from compromised workstations to electronic health record (EHR) systems, enabling large-scale data breaches |

| Default system credentials | Unauthorized access, privilege escalation, insider misuse | Initial Access, Privilege Escalation | Medical devices and administrative systems deployed with factory-default passwords have enabled attackers to gain unauthorized access to clinical systems |

| Insecure firmware | Persistent malware, backdoor installation, stealth attacks | Persistence, Defense Evasion | Unverified firmware updates in medical devices can allow attackers to implant persistent backdoors that survive system reboots, posing long-term risks to patient safety |

| Unencrypted data storage or transmission | Eavesdropping, data leakage, man-in-the-middle attacks | Collection, Exfiltration | Unencrypted transmission of patient data over internal hospital networks has resulted in exposure of personally identifiable information (PII) and protected health information (PHI) |

| Legacy systems lacking modern security controls | Exploit-Kit-based attacks, Ransomware, exploitation of known vulnerabilities, denial-of-service | Initial Access, Impact | Older healthcare information systems lacking MFA, endpoint protection, or intrusion detection remain highly vulnerable to modern ransomware and denial-of-service attacks |

| Aspect | HIPAA | GDPR |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Applicability | U.S.-based healthcare providers, insurers, and business associates | All organizations processing personal data of EU residents |

| Type of Data Covered | Protected Health Information (PHI) | Personal data and special category data, including health data |

| Breach Notification Window | Within 60 days of breach discovery | Within 72 h of breach discovery |

| Encryption Requirement | Addressable safeguard; recommended but not mandatory | Explicitly encouraged through encryption and pseudonymization |

| Access Control | Role-based access controls required | Principle of least privilege and access minimization |

| Data Minimization | Not explicitly defined | Explicitly mandated as a core principle |

| Patient/Data Subject Rights | Right to access and amend records | Rights to access, rectification, erasure, and data portability |

| Cross-Border Data Transfer | No explicit restrictions | Strict controls requiring adequacy decisions or safeguards |

| Penalties for Non-Compliance | Civil and criminal penalties with capped fines | Fines up to EUR 20 million or 4% of global annual turnover |

| Privacy by Design | Not explicitly required | Explicitly mandated by regulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qureshi, R.; Koo, I. A Comprehensive Survey of Cybersecurity Threats and Data Privacy Issues in Healthcare Systems. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031511

Qureshi R, Koo I. A Comprehensive Survey of Cybersecurity Threats and Data Privacy Issues in Healthcare Systems. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031511

Chicago/Turabian StyleQureshi, Ramsha, and Insoo Koo. 2026. "A Comprehensive Survey of Cybersecurity Threats and Data Privacy Issues in Healthcare Systems" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031511

APA StyleQureshi, R., & Koo, I. (2026). A Comprehensive Survey of Cybersecurity Threats and Data Privacy Issues in Healthcare Systems. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031511