1. Introduction

Hydraulic shaking tables are used in structural seismic testing due to their large output force, long stroke, and high velocity [

1]. In 6-degree-of-freedom shaking table systems, four redundant actuators are often employed in the horizontal direction to fulfill high load capacities and stability. However, in these coupled systems, manufacturing/installation errors, asymmetric load distribution, uneven actuation forces, and the inherent nonlinear hysteresis could add extra stresses to the platform [

2,

3]. This results in fatigue damage of crucial parts, weak system tracking accuracy, and severely complicates the table’s ability to reproduce complex excitation waveforms [

4].

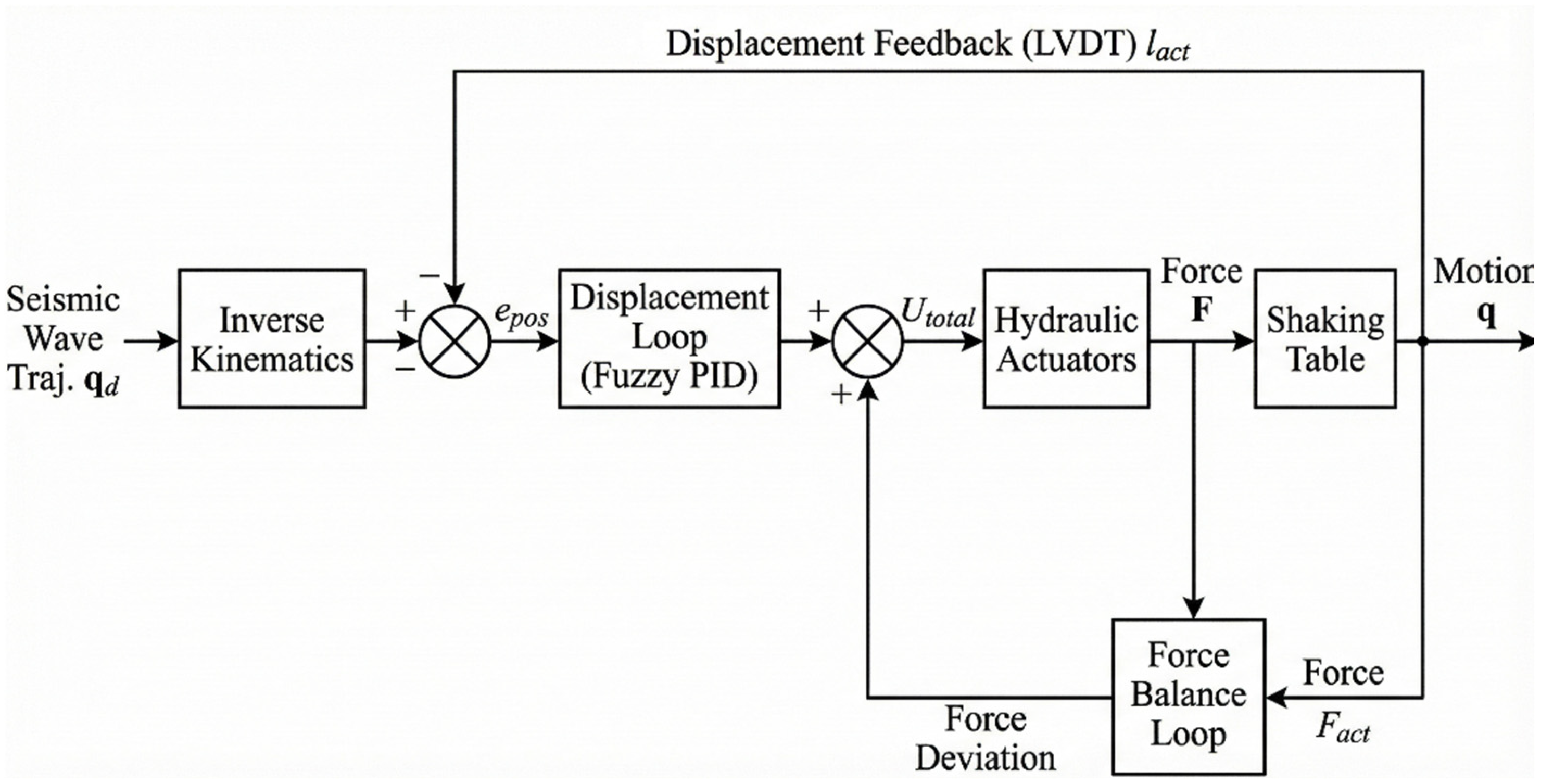

The control system for shaking tables presents a number of challenges. First, the system’s multivariable highly coupled dynamics, particularly the inherent internal force couplings resulting from the

Z-axis redundant actuator, impact platform posture and tracking accuracy [

5]. Second, the intrinsic nonlinearity and phase lag in hydraulic systems severely impair the efficiency of traditional linear controllers under broadband excitation [

6]. Finally, the time-dependent loads and the requirement for broadband excitations require the control system to be robust to these requirements.

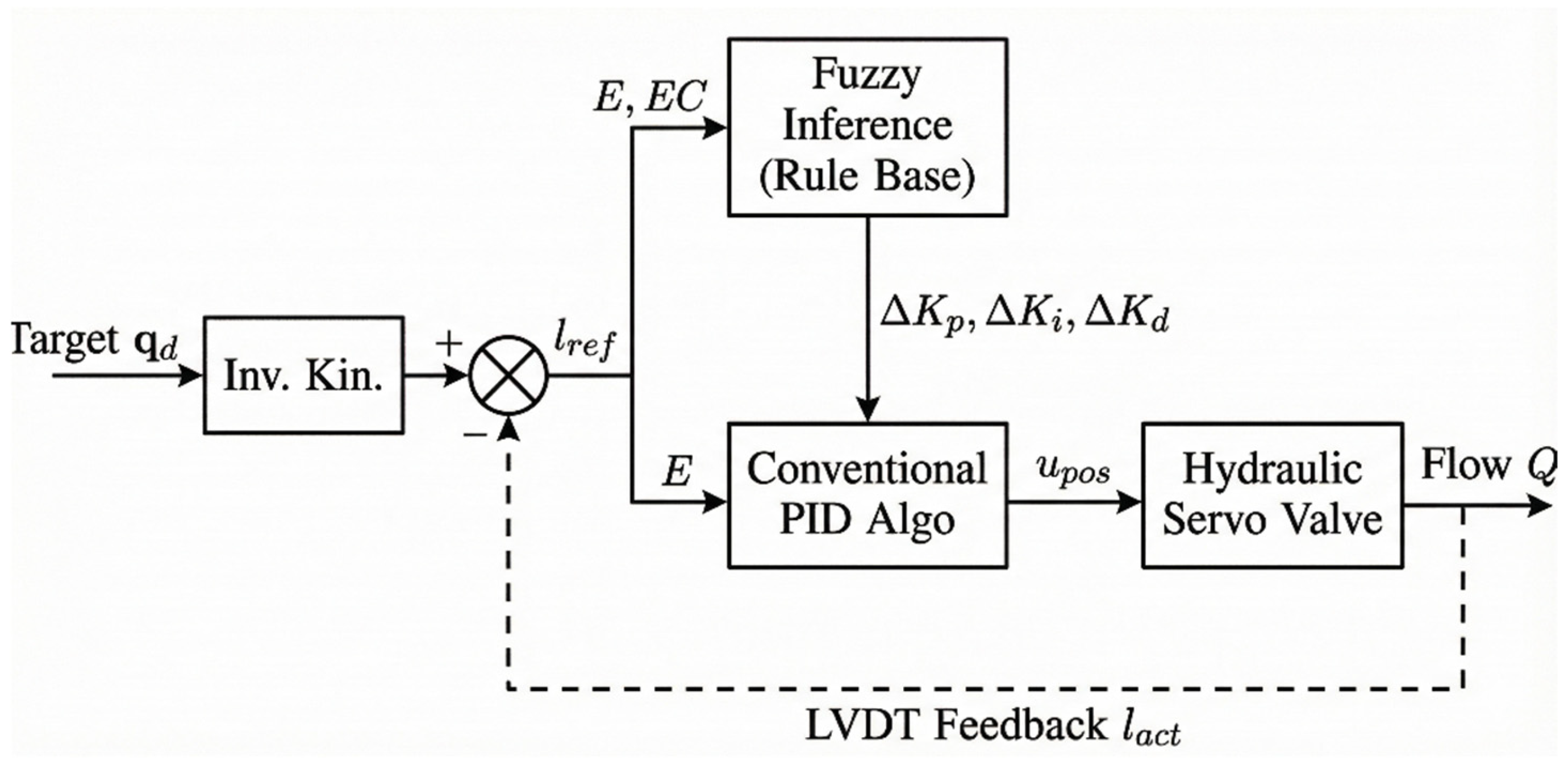

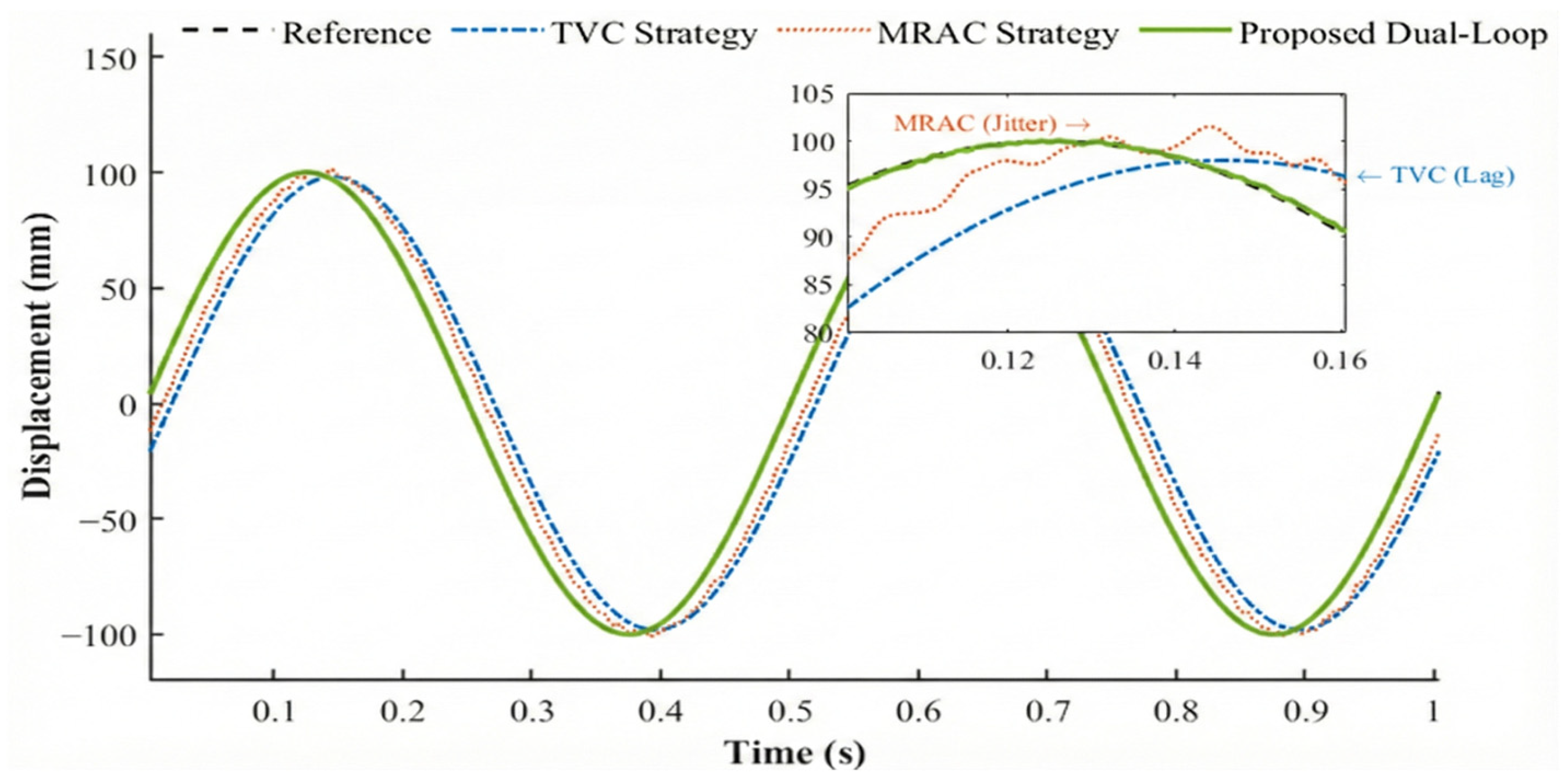

To address these challenges, various control strategies have been developed. The Three-Variable Control (TVC) [

7] is the industry standard, utilizing feedback of acceleration, velocity, and displacement to extend bandwidth. However, as a linear fixed-gain strategy, TVC lacks the adaptability to handle the strong coupling in redundant mechanisms. Iterative Learning Control (ILC) [

8] excels in improving tracking for repetitive waveforms but fails to suppress instantaneous internal force coupling in non-repetitive seismic tests. Other approaches, such as the kinematic-based strategy by Guan [

9] and the deformation-coupling model by Wei [

10], have made progress in theoretical decoupling. Liao Yang [

11] utilized sliding mode control and adaptive inverse control techniques to eliminate alien disturbance forces and compensate for system uncertainties, thereby achieving random vibration control for acceleration. To further enhance the fidelity of seismic reproduction, researchers have extensively explored advanced compensation strategies. Ren et al. [

12] investigated a dual-loop hybrid control method for electro-hydraulic shaking tables, demonstrating that combining pressure feedback with displacement control can effectively improve system damping and stability. In terms of frequency-domain compensation, Ji et al. [

13] developed a power-exponent feedforward method, which significantly reduces the amplitude and phase tracking errors in the high-frequency band. Similarly, Li et al. [

14] introduced a jerk-based control technique, utilizing the derivative of acceleration to smooth the trajectory and reduce mechanical impact during seismic reproduction. Furthermore, intelligent optimization algorithms have been applied to controller tuning; for instance, Gao et al. [

15] employed a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to auto-tune the PID parameters, achieving better transient response than manual tuning. Zhang et al. [

16] also proposed a hybrid control strategy for dual-shaking tables, emphasizing the importance of synchronized optimization. While they have advanced the state of the art in single-axis or decoupled control, they often treat kinematic errors and force tracking as separate problems. Consequently, they rarely address the specific ‘fighting’ issue caused by redundant actuation in multi-DOF systems, nor do they fully resolve the fundamental conflict between rigid position constraints and flexible force distribution under the influence of hydraulic nonlinearities [

17].

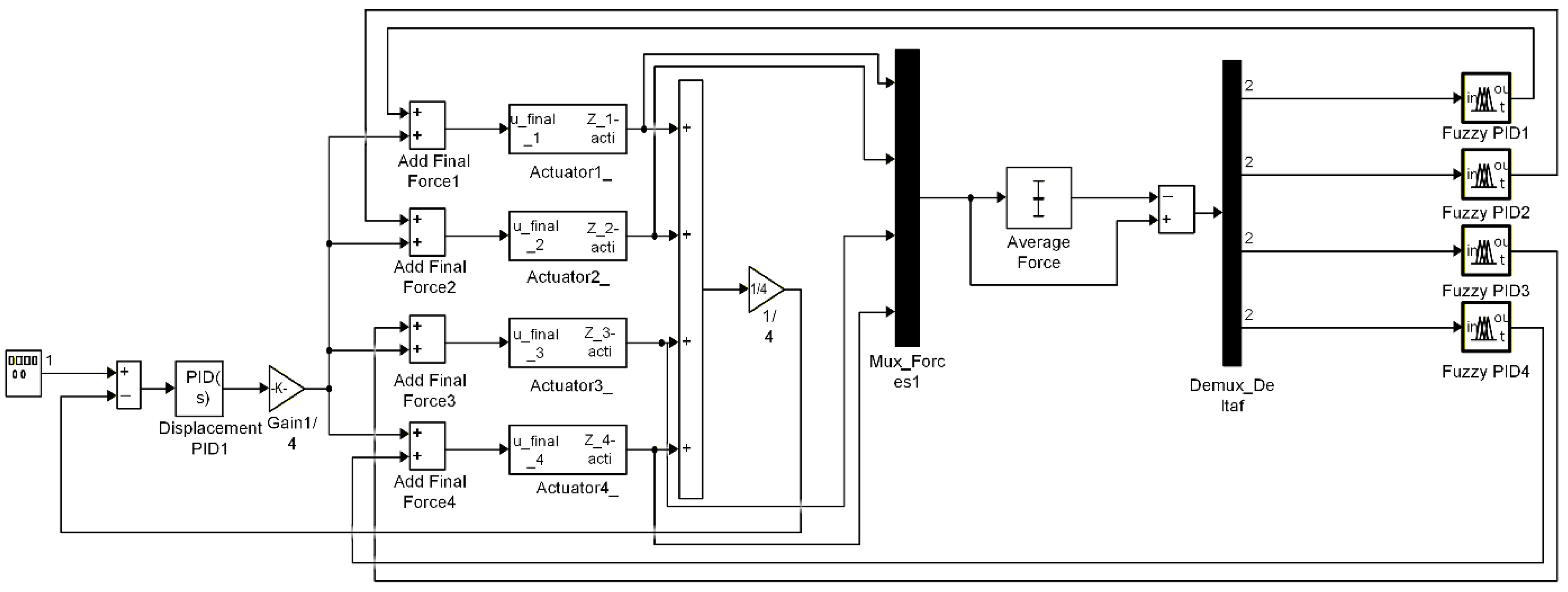

To bridge this gap, this paper proposes a displacement–force dual closed-loop cooperative control method. Unlike previous approaches that prioritize either position accuracy or force equalization, our strategy integrates a Fuzzy PID controller within a dual-loop architecture. This allows for real-time kinematic decoupling for trajectory tracking, and active compliance control for internal force minimization, thereby achieving a trade-off optimization between tracking precision and structural safety.

2. Model Construction of the Seismic Simulation Shaking Table

2.1. System Configuration and Modeling Assumptions

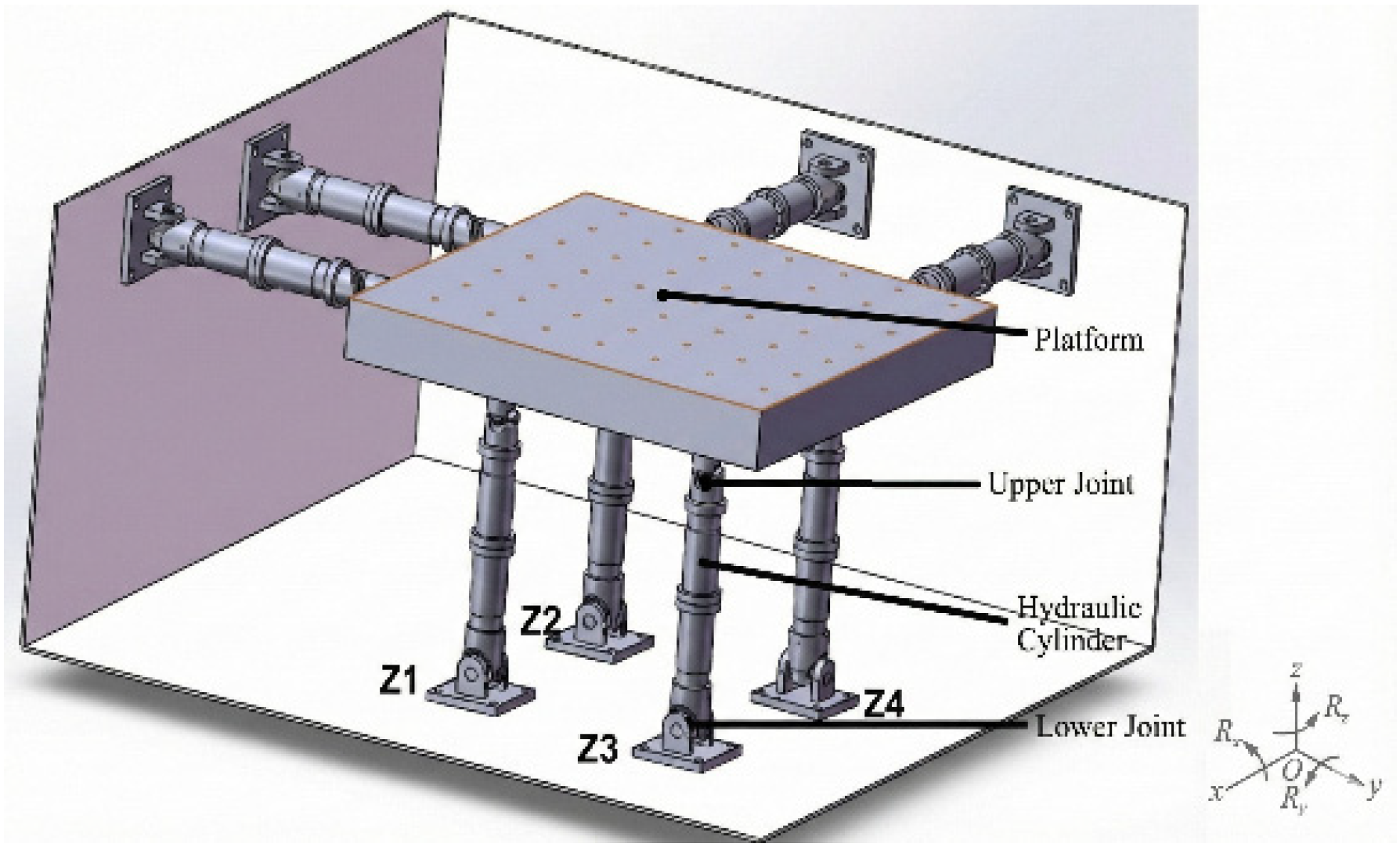

The experimental platform utilized in this study is a custom-developed 3 × 3 m 6-DOF hydraulic shaking table prototype, designed and constructed by the authors’ research group at Taiyuan University of Science and Technology. This prototype serves as a testbed for validating the proposed control strategies. The earthquake simulation system studied in this paper employs a spatially redundant parallel mechanism specifically designed for high-fidelity payload reproduction. Unlike the widely used Stewart platform (hexapod), which utilizes six inclined actuators to realize 6-DOF motion, this study adopts an orthogonal redundant actuation layout (n = 8 inputs driving m = 6 DOFs). The rationale for selecting this orthogonal configuration lies in its superior kinematic decoupling and load-carrying capacity. In a standard Stewart platform, the inclined orientation of the actuators results in strong coupling between vertical and horizontal forces. Conversely, the proposed orthogonal design allows the four vertical actuators (

) to directly bear the gravitational load without inducing parasitic horizontal components, thereby significantly enhancing the vertical payload capacity. Additionally, the redundant arrangement of these actuators at the four corners provides a larger resisting moment arm against overturning, which is critical for testing tall, heavy civil engineering structures that generate high overturning moments. However, this redundancy inherently introduces static indeterminacy (over-constraint), necessitating the specialized dual-loop control proposed in this study to actively manage the internal force distribution. As illustrated in the system schematic (refer to

Figure 1), the actuation architecture is categorized into two decoupled functional groups. The Vertical Group consists of four actuators (

) symmetrically mounted underneath the table corners; these actuators support the gravitational load and govern the vertical translation (

), roll (

), and pitch (

) motions. Complementing this, the Horizontal Group comprises four actuators arranged orthogonally, with two attached to Side-A (

X-axis) and two to Side-B (

Y-axis), which collaboratively drive the horizontal translations (

) and yaw rotation (

).

To facilitate the mathematical derivation and ensure the tractability of the control design, several standard assumptions are adopted regarding the system dynamics. First, both the moving platform and the base are modeled as ideal rigid bodies, neglecting any elastic deformation during operation. Second, the mechanical connections between the actuators and the platform are assumed to utilize frictionless spherical joints to simplify the kinematic constraints. Finally, the bulk modulus of the hydraulic fluid and the hydraulic supply pressure are considered constant parameters throughout the dynamic analysis.

An inertial coordinate frame is established at the foundation center, while a moving coordinate frame is attached to the geometric center of the platform. The generalized pose vector describing the platform’s motion is explicitly defined as , where denote the translational displacements along the three axes, and represent the rotational angles (roll, pitch, yaw) about the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. The system is driven by eight hydraulic actuators, indexed by , where actuators constitute the vertical group and constitute the horizontal group. This redundant configuration (n = 8 inputs driving m = 6 DOFs) is specifically adopted to enhance the vertical load-carrying capacity and the resistance to overturning moments compared to standard 6-actuator Stewart platforms, thereby meeting the rigorous requirements of heavy-duty seismic simulation.

2.2. Kinematic Formulation

To achieve precise mapping from the platform’s desired pose to individual actuator extensions—thereby providing setpoints for the displacement control loop—the inverse kinematics of the system must be formulated. Based on the closed-loop vector chain method, the length vector

of the

i-th actuator is expressed as:

where

denotes the translation vector of {

},

represents the rotation matrix derived from the

Euler angle sequence; and

and

are the position vectors of the upper and lower hinge points, respectively. The scalar control input is given by the Euclidean norm

.

Differentiating Equation (1) with respect to time yields the differential kinematic relationship:

where

is the system Jacobian matrix. A critical characteristic of this orthogonal configuration is that

is a non-square matrix with full column rank. This geometric over-constraint (8 inputs driving 6 outputs) implies that strictly coupled constraints exist among the actuators. Theoretically, the inverse kinematic solution is unique for a rigid body; however, in practice, manufacturing tolerances and installation errors disrupt this geometric consistency, necessitating the consideration of force–level coupling.

2.3. Dynamic Modeling and Force Indeterminacy

The dynamic behavior of the platform is governed by the rigid-body equations of motion derived via the Newton–Euler formulation [

18]. While the general formulation follows the standard Newton–Euler approach adapted from robotic dynamics literature, the specific force distribution model for this orthogonal redundant configuration is derived as follows. Considering the platform mass and inertia, the dynamic equilibrium in the task space is:

where

is the symmetric positive-definite inertia matrix,

represents the vector of Coriolis and centrifugal forces,

is the gravity vector, and

is the generalized driving force vector acting on the DOFs.

According to the principle of virtual work, the mapping between the actuator output forces

(where components

correspond to the

i-th actuator) and the generalized force

is established as:

Substituting Equation (4) into Equation (3) yields the relationship between the actuator forces and the platform motion. The physical utility of this formulation is to reveal the fundamental indeterminacy of the redundant system. Since the Jacobian matrix

is non-square (

), the inverse mapping from the required generalized force

to the actuator driving forces

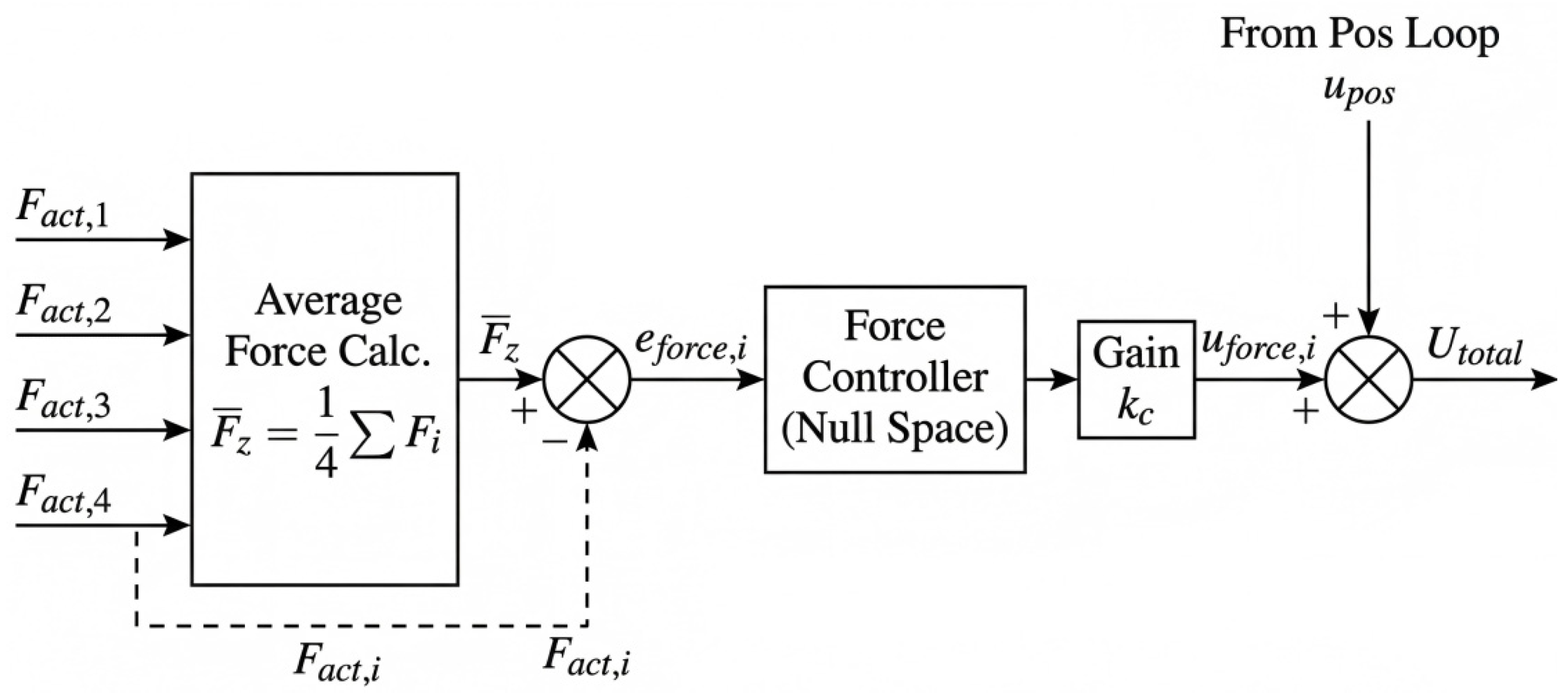

is not unique. This mathematical property allows the actuator force vector to be decomposed into two orthogonal components: the motion-inducing force and the internal null-space force. Equation (5) below provides the mathematical basis for this decomposition, which is the theoretical foundation of the proposed dual-loop control strategy.

where

denotes the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse, and

represents the total dynamic load. The first term

represents the minimum-norm force required to drive the motion. The second term (

) resides in the null space of

and represents the internal forces. The vector

is arbitrary, indicating that infinite force combinations can produce the same motion. Without active regulation,

is determined uncontrolledly by structural stiffness and geometric errors, leading to the “fighting” phenomenon between actuators.

2.4. Mechanism of Z-Axis Internal Force Coupling

This study specifically targets the coupling within the Vertical Group (). Due to the static indeterminacy described in Equation (5), the four vertical actuators form a hyperstatic structure. Ideally, the load should be distributed symmetrically. However, physical inconsistencies (e.g., sensor drift, mounting errors ) violate the ideal constraint surface. To quantify the mechanism of ‘actuator fighting’, we establish the relationship between kinematic error and internal force.

Based on the geometric compatibility condition and Hooke’s law, the antagonistic internal force induced by a kinematic mismatch

can be approximated by:

where

represents the equivalent stiffness of the hydraulic oil column. The utility of this formulation extends beyond physical modeling, it reveals the fundamental limitation of single-loop control. Given the high bulk modulus of hydraulic fluid, the equivalent stiffness

is typically very large (>10

7 N/m). Consequently, even a sub-millimeter geometric error (

) is amplified into a significant internal force distortion. This parasitic force does not contribute to the platform motion but generates structural stress, consumes hydraulic energy, and accelerates seal wear. It is important to note that Equation (6) represents a linearized model of the force–structure interaction. In actual operation, the system exhibits complex structural non-linearities (e.g., joint friction and time-varying stiffness). Instead of establishing a high-order complex model which is difficult to identify in real-time, this study treats these unmodeled structural non-linearities as lumped disturbances. The proposed control strategy relies on the adaptive capability of the Fuzzy logic (

Section 3.4) to compensate for these uncertainties online, ensuring the control robustness without requiring an explicit non-linear structural model. Therefore, the proposed dual-loop control strategy is essential to actively regulate the null-space component

toward zero.

2.5. Linearized Model of Hydraulic Actuator

To facilitate the control system design, the dynamics of the valve-controlled hydraulic cylinder are modeled. Each actuator is driven by a critical-center servo valve. Neglecting minor leakage and assuming the dynamic response of the servo valve is significantly faster than the hydraulic natural frequency, the linearized flow equation for the

i-th actuator is given by:

where

is the load flow,

is the valve spool displacement,

is the load pressure difference,

is the flow gain, and

is the flow-pressure coefficient.

Applying the continuity equation to the cylinder chambers yields:

where

is the effective piston area,

is the total leakage coefficient,

is the total control volume, and

is the effective bulk modulus.

Finally, the force balance equation for the piston rod is:

where

is the equivalent mass of the piston rod and

is the viscous damping coefficient. Combining Equations (7)–(9), the plant model relating the valve input

to the output force

and displacement

is established. This third-order hydraulic dynamics, coupled with the rigid-body dynamics derived in

Section 2.3, constitutes the complete plant model for the subsequent controller design.

5. Shaking Table Experiments and Result Analysis

The experimental validation was conducted on a 3 × 3 m 6-DOF hydraulic shaking table prototype. This platform was designed and constructed specifically by the authors’ research group at Taiyuan University of Science and Technology to serve as an open-architecture testbed for redundant actuation research. Unlike commercial systems with encapsulated controllers, this custom-developed prototype allows direct access to the underlying servo control loops, which is essential for implementing the proposed dual-loop strategy.

In practice, the key metrics for evaluating control strategies for shaking tables primarily include: acceleration waveform distortion, signal-to-noise ratio, non-uniformity, transverse ratio, and displacement waveform distortion [

25]. This paper takes acceleration waveform distortion as an example. The formula for acceleration waveform distortion is given by:

where

is Amplitude of the

i-th harmonic component of the acceleration output signal,

is Amplitude of the fundamental component of the acceleration output signal.

In addition to THD, to strictly quantify the performance enhancement reported in the simulation and experimental sections (e.g., the reduction in internal force), the percentage improvement rate (

) is calculated as:

where

represents the peak metric (e.g., maximum internal force or tracking error) under the baseline single-loop control, and

is the corresponding metric under the proposed dual-loop control.

Taking the output of the center-table acceleration sensor as the primary reference, the distortion of the acceleration waveform of the shaking table was tested. The test parameters are listed in

Table 3.

To ensure rigorous data acquisition, the experimental system is equipped with high-precision sensors and a real-time control platform. The platform states are measured using magnetostrictive displacement sensors (MTS Series, resolution < 1 μm) and capacitive accelerometers (PCB Series, bandwidth 0–100 Hz). The control algorithm is implemented on a dSPACE real-time simulation system (DS1104) with a sampling frequency set to 1 kHz. During data post-processing, the raw acceleration signals were processed using a zero-phase low-pass Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 50 Hz to eliminate high-frequency measurement noise while preserving the fidelity of the waveform in the effective bandwidth.

Three experimental groups [

26], as specified in

Table 4, were conducted using a sinusoidal input signal with an amplitude of 0.2 g and a frequency of 10 Hz.

In the experimental validation phase, this study focuses on the Fixed-Frequency Sinusoidal Test (10 Hz, 0.2 g), a specific regime selected to serve as a rigorous ‘stress test’ for the control strategy. The frequency of 10 Hz was chosen because it lies within the critical hydraulic resonance bandwidth of the system, where the phase lag caused by fluid compressibility is most pronounced and flow-pressure nonlinearity is severe. Simultaneously, the amplitude of 0.2 g was selected because, under this 10 Hz excitation, it generates sufficient inertial force to induce significant dynamic coupling between the redundant actuators. The expectation by using these combined values is to explicitly expose the ‘actuator fighting’ phenomenon and the harmonic distortion caused by the hydraulic dead-zone. Consequently, achieving low Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) under this challenging condition serves as robust evidence of the proposed dual-loop controller’s superiority in handling system nonlinearities and geometric over-constraints.

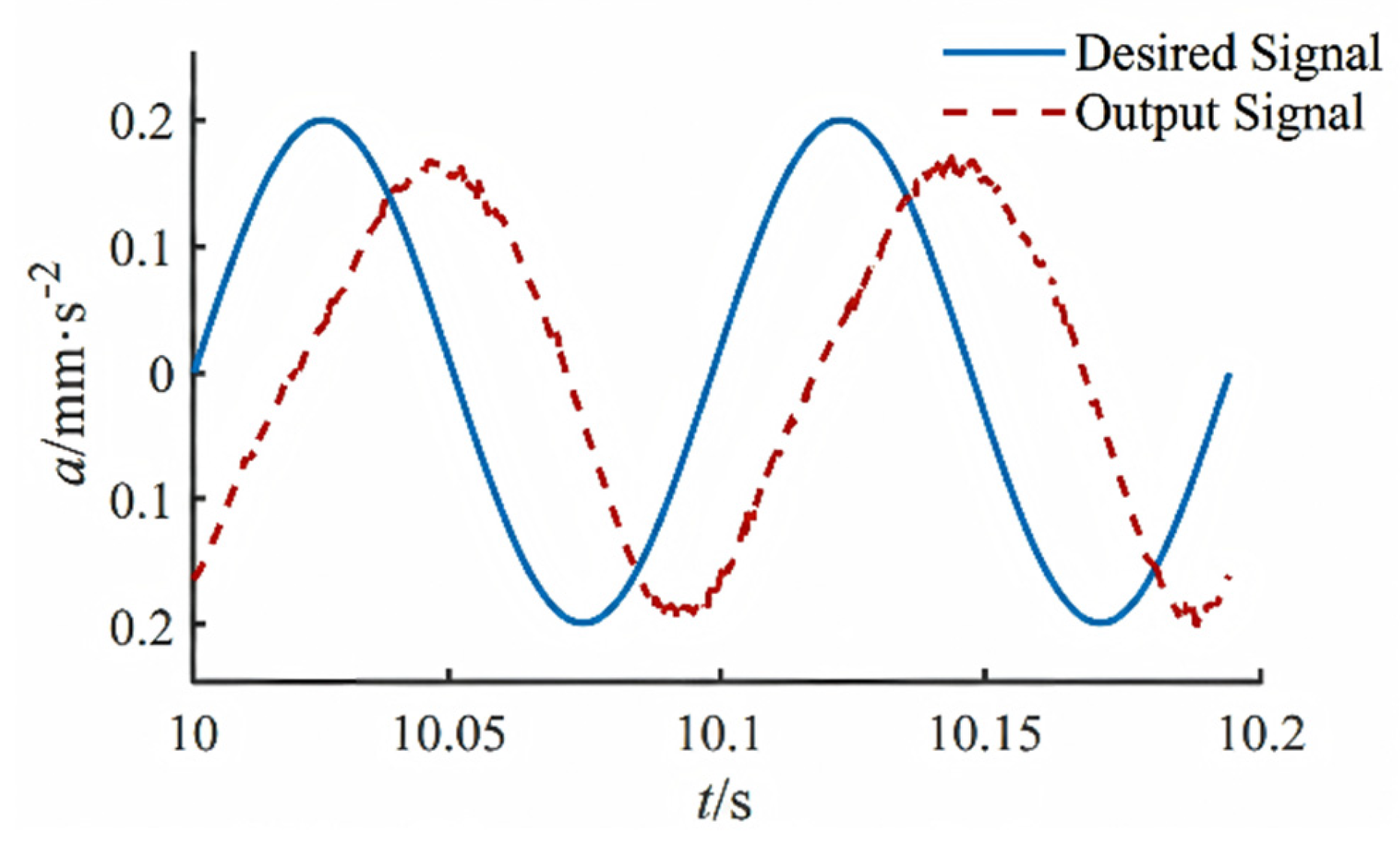

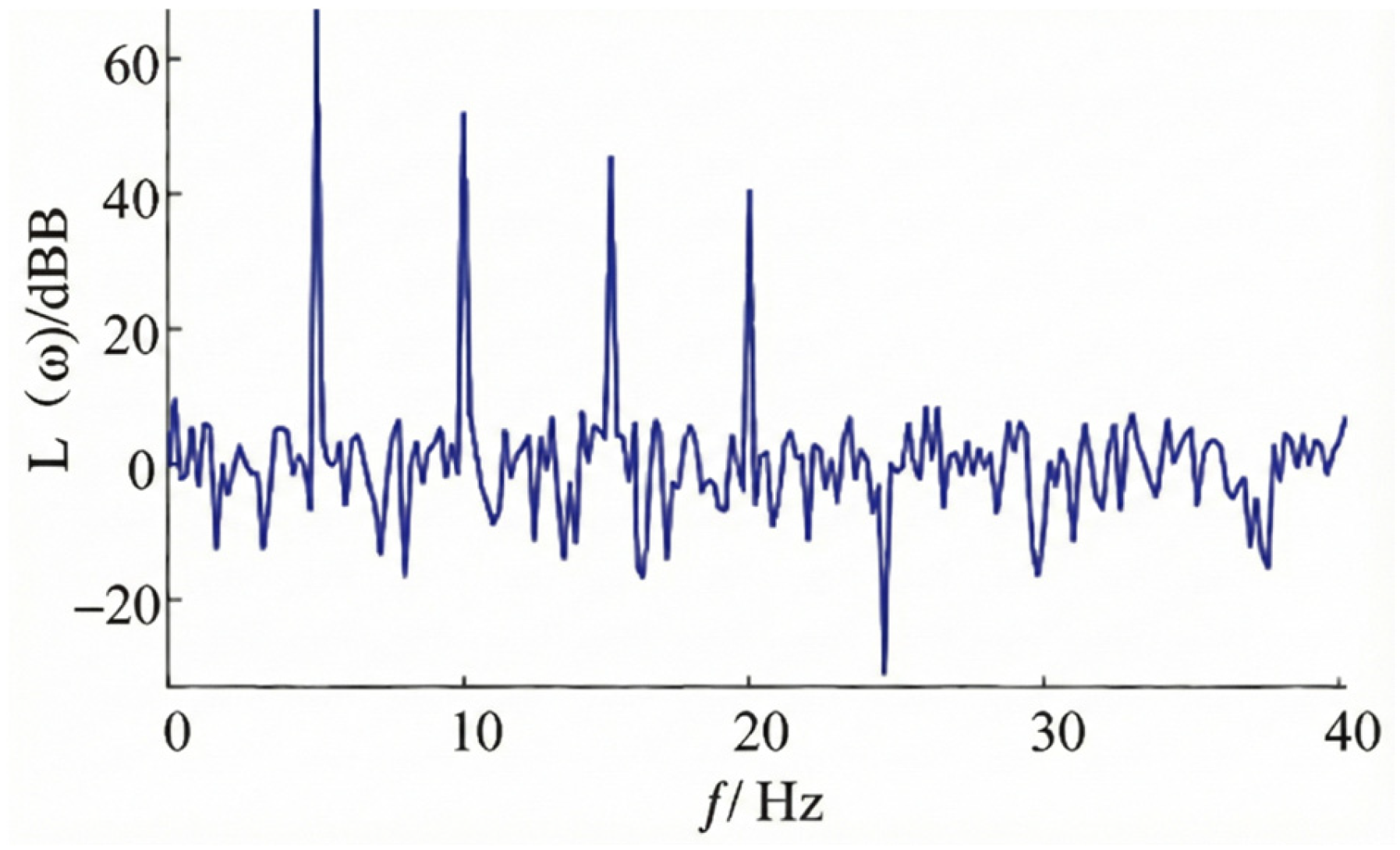

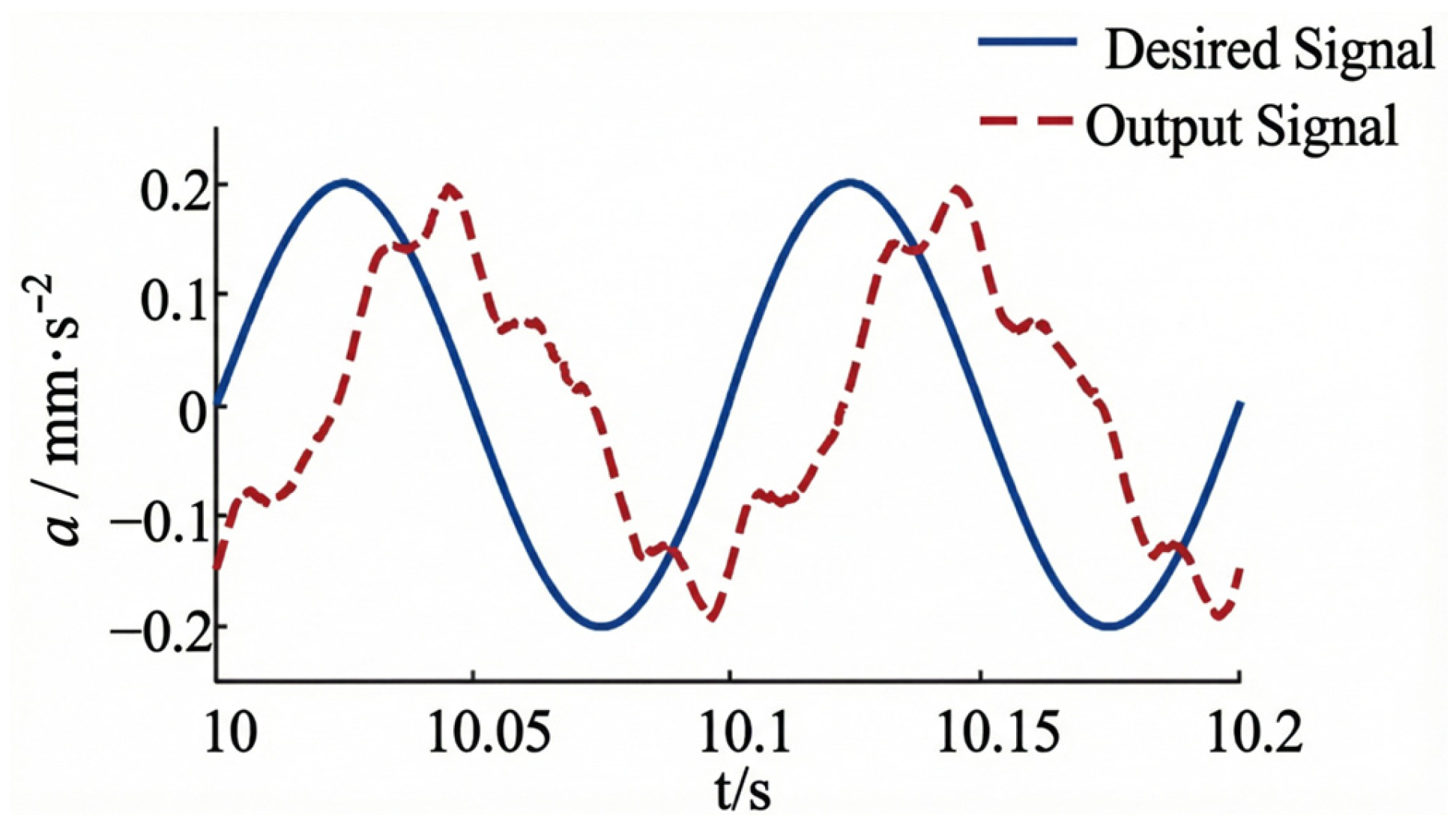

For Group 1, as shown in

Figure 11, the tracking curve exhibits significant amplitude attenuation (0.34 g actual vs. 0.4 g target). The amplitude spectrum in

Figure 12 reveals a Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of 15.2%. The prominence of higher-order harmonics (20 Hz, 30 Hz peaks) in the spectrum indicates that the single-loop controller fails to linearize the hydraulic system.

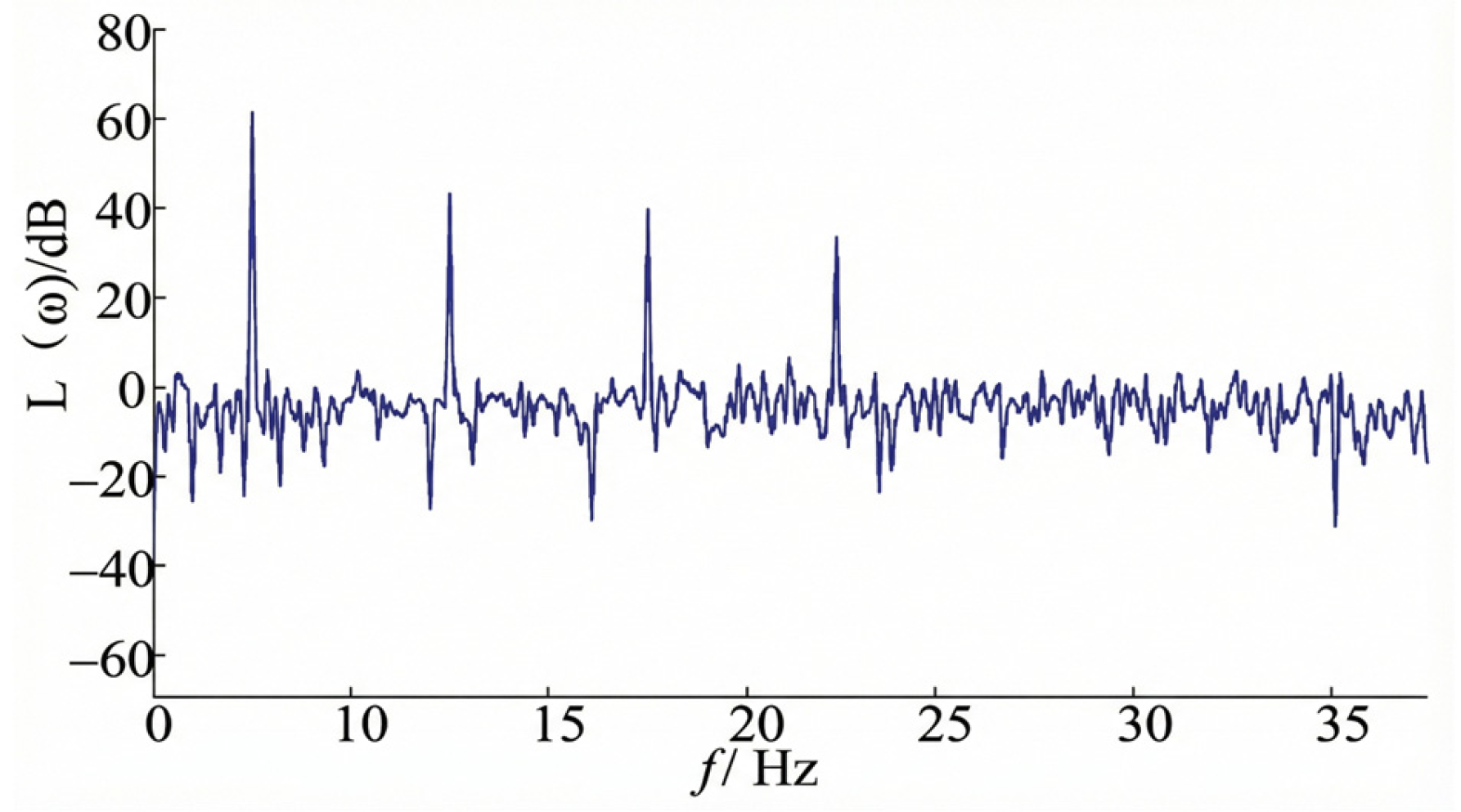

For Group 2, the lack of position constraints results in waveform drift, as shown in

Figure 13. Although the peak-to-peak value increases to 0.392 g,

Figure 14 shows a THD of 17.8%. The chaotic spectrum distribution indicates that without the kinematic stiffness provided by the displacement loop, the system cannot maintain stable trajectory tracking.

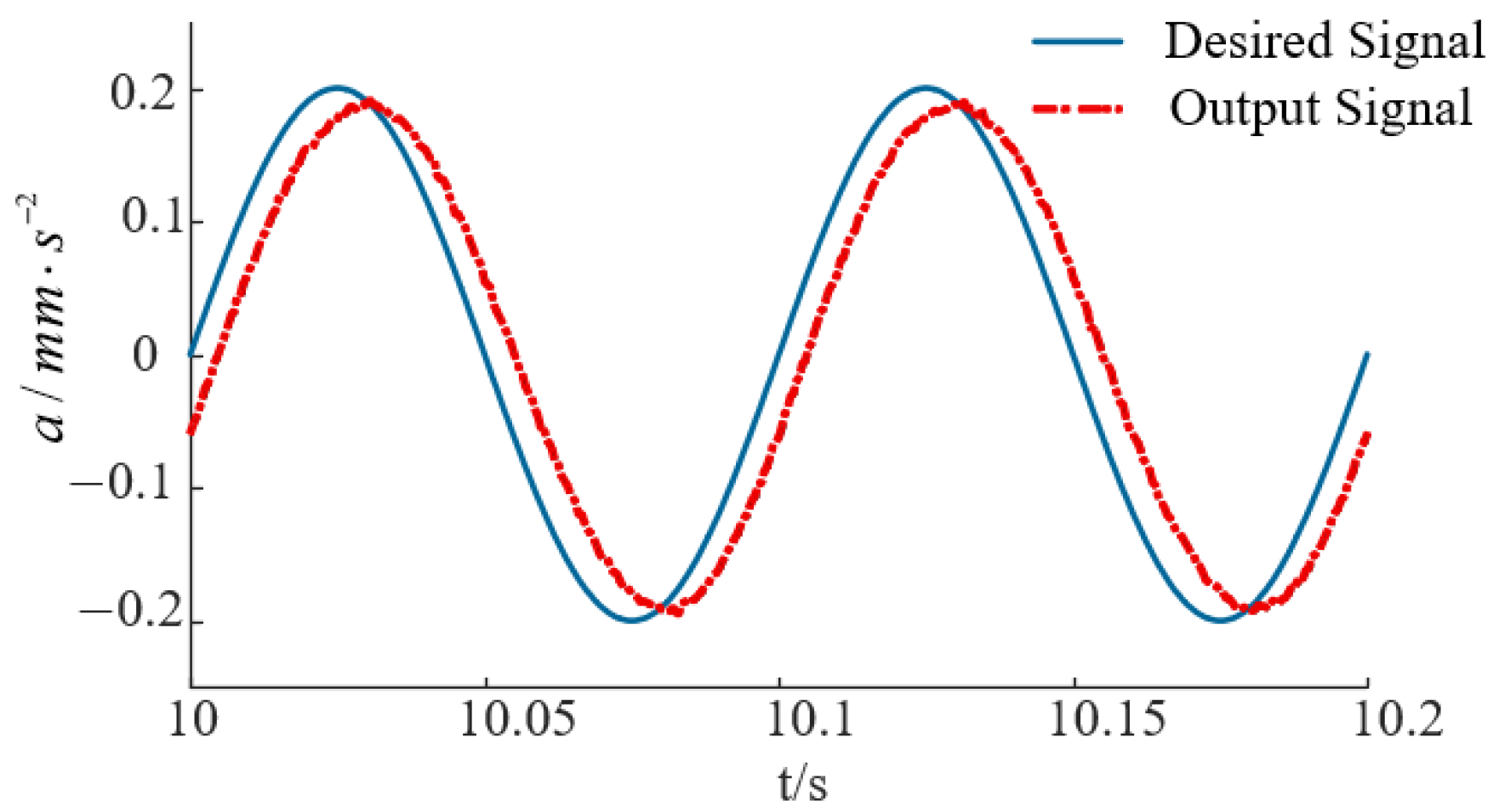

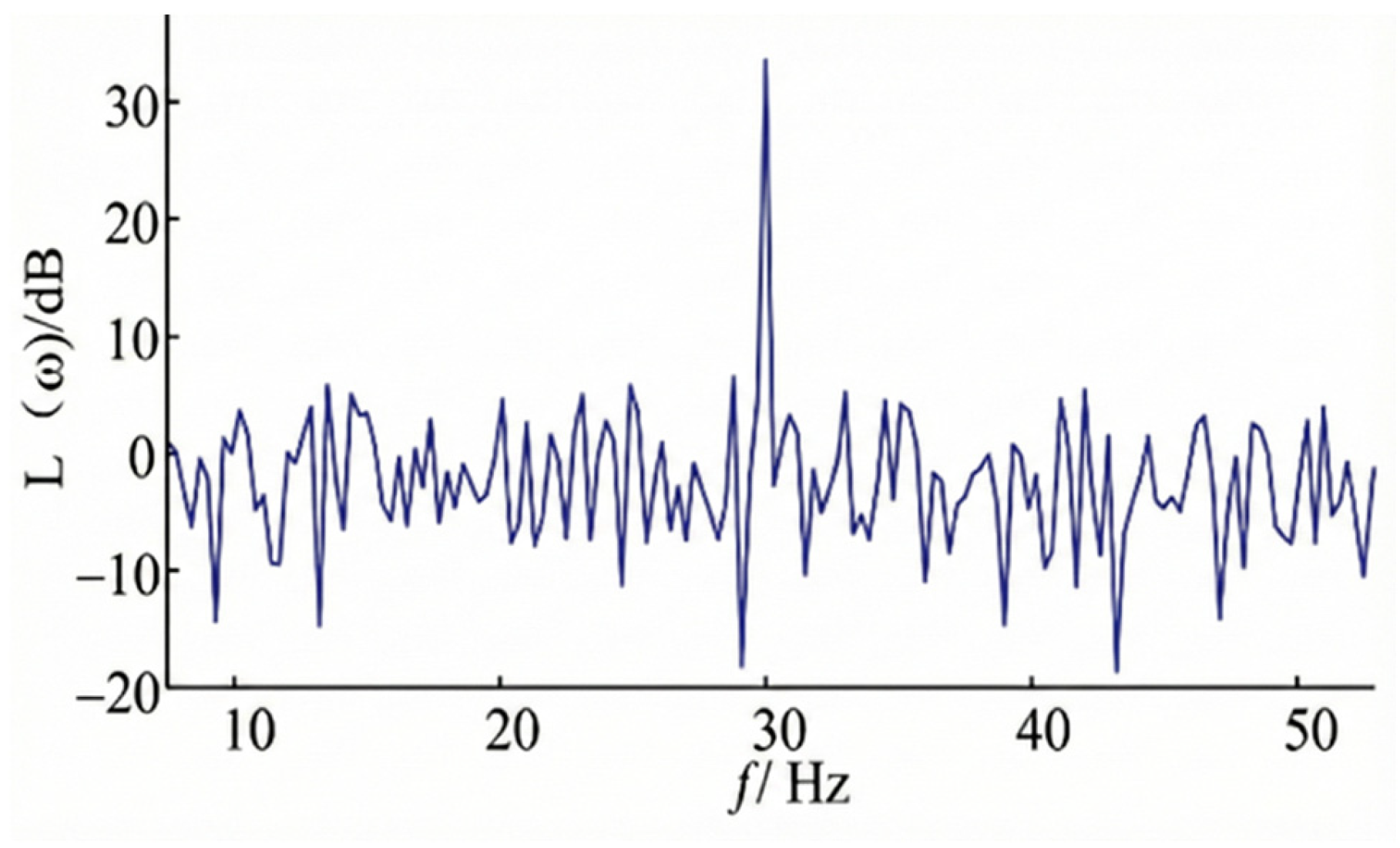

For Group 3 (Dual-Loop),

Figure 15 shows that the output signal closely matches the reference with a peak-to-peak value of 0.412 g, effectively compensating for the amplitude loss seen in Group 1. Most importantly, the amplitude spectrum in

Figure 16 demonstrates a clean spectral response. The harmonic components are suppressed, reducing the THD to 3.2%. This 79% reduction in distortion (compared to Group 1) confirms the proposed method’s capability to linearize the system output under critical resonance conditions.

THD is a key metric for evaluating the waveform-reproduction fidelity of shaking tables. The proposed method reduces THD to a level well below the standard threshold (typically required to be below 10%), demonstrating its effectiveness in suppressing harmonic distortion caused by system nonlinearities and internal force coupling. This capability is particularly critical in practical seismic-simulation tests: it ensures that the excitation signal loaded onto the test specimen is more precise, thereby yielding more reliable structural dynamic-response data and substantially enhancing the accuracy and engineering-guidance value of the test results [

27]. The experimental results presented in

Table 5 demonstrate that the proposed dual-loop control strategy reduces the total harmonic distortion (THD) of the output acceleration signal to 3.2%, which is significantly lower than that achieved by the displacement single-loop control (15.2%) and the force single-loop control (17.8%). According to the general engineering criterion for high-fidelity shaking-table testing, which typically requires a THD below 10%, the dual-loop strategy fully satisfies the specification. In contrast, both single-loop strategies exceed the allowable THD limit, exhibiting noticeable waveform distortion [

28].

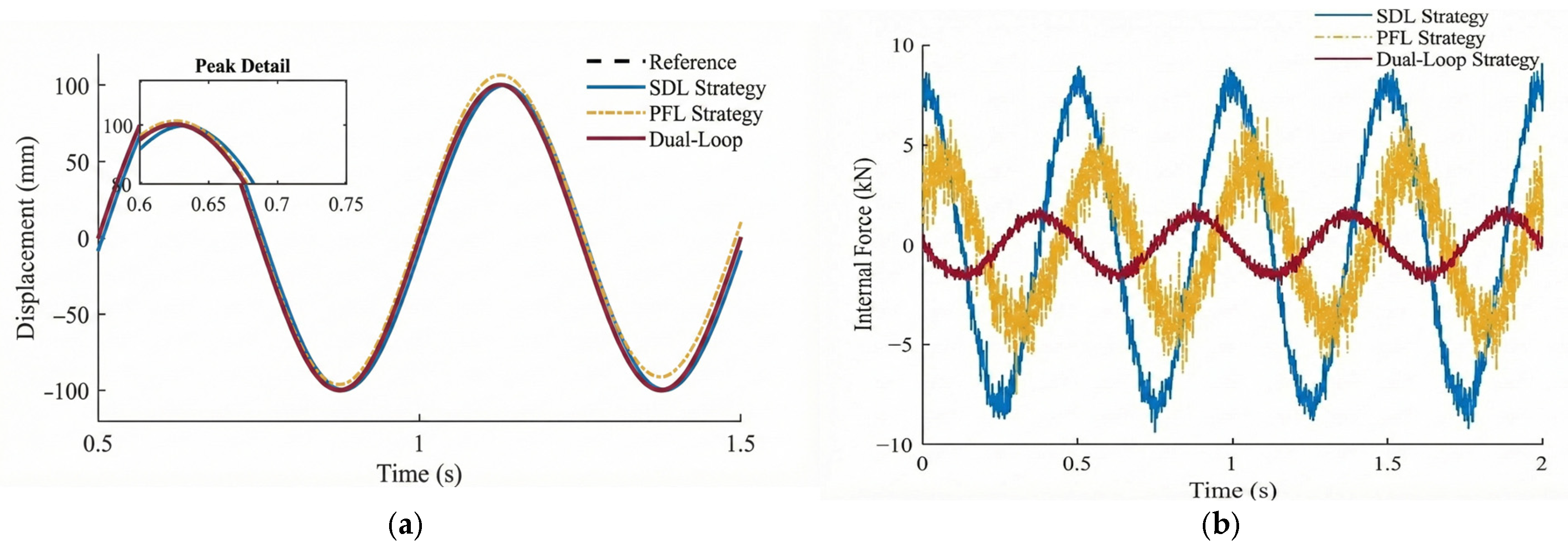

To rigorously validate the model’s handling of force-structure interactions, this study extends the performance metric beyond simple kinematic accuracy. As evidenced by the Internal Force Fluctuation analysis (specifically the 87% suppression shown in the ablation studies), the system effectively actively manages the redundant constraints. This reduction in internal fighting provides direct physical validation that the dual-loop controller correctly models and regulates the dynamic interaction between the hydraulic actuators and the rigid platform structure.

The experimental validation on the 3 × 3 m prototype raises the question of how the proposed strategy scales to platforms of different sizes or masses. Regarding robustness to payload variations, the reduction ratio of internal forces is theoretically insensitive to mass changes. The force balance loop regulates the null-space force component, which is primarily induced by geometric kinematic inconsistencies (e.g., installation errors

in Equation (6)) rather than the inertial load. Therefore, even if the payload mass changes, the controller continues to actively eliminate the differential geometric conflict. Regarding dimensional scalability, the proposed dual-loop architecture is mathematically generalized. Since the control law is formulated based on the system Jacobian matrix (Equation (2)) and the pseudo-inverse force distribution (Equation (5)), it is structurally independent of specific geometric dimensions. For platforms of different sizes (e.g., 6 × 6 m) or varying tonnage, the control strategy remains valid provided the actuator configuration follows the same orthogonal redundancy principle; one simply needs to update the geometric parameters in the kinematic model. Furthermore, the Adaptive Fuzzy PID (

Section 3.4) inherently compensates for the changes in hydraulic natural frequency that accompany size scaling, ensuring consistent performance across different scales.

6. Conclusions

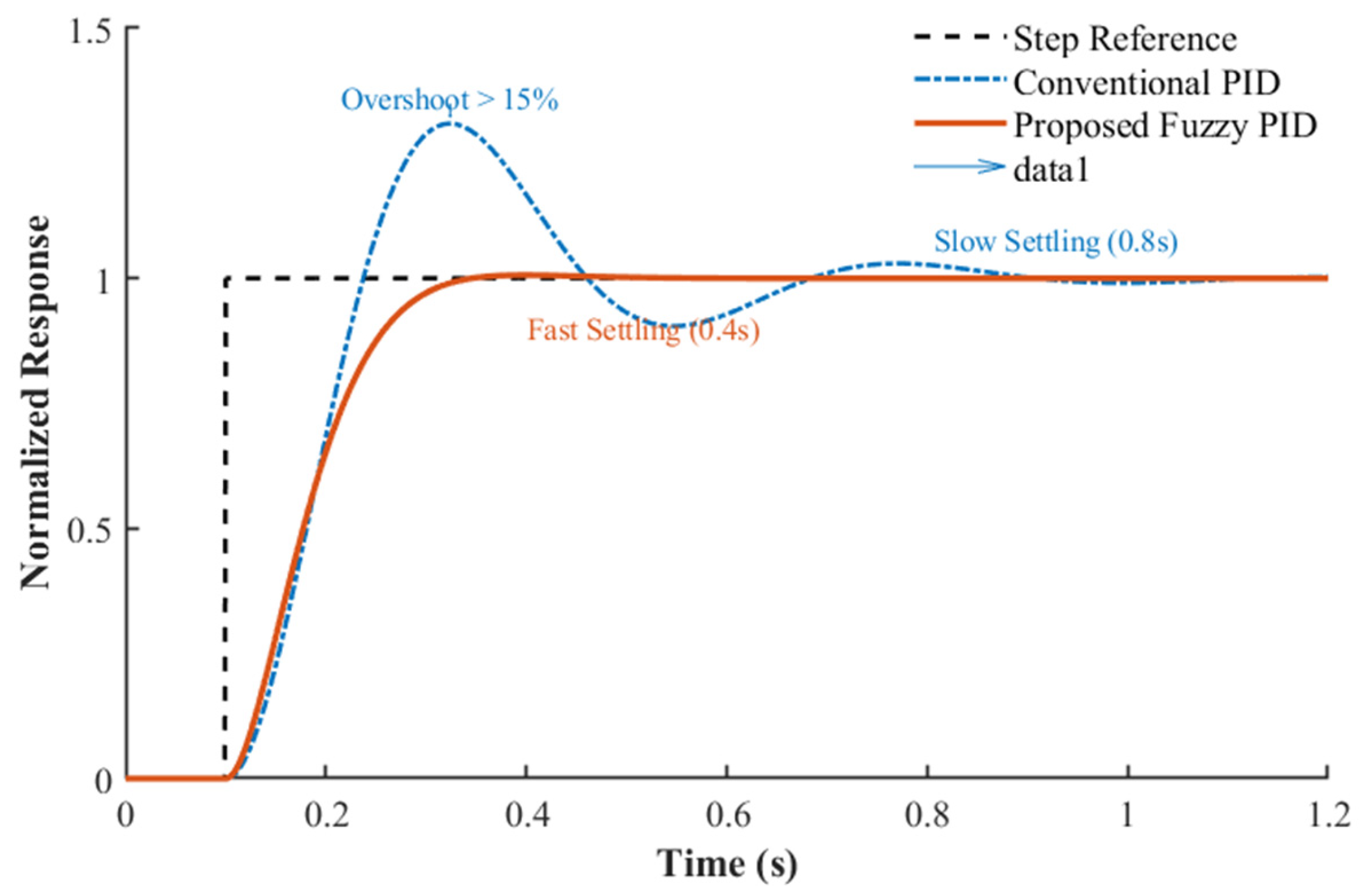

This paper addresses the critical challenges of internal force coupling and hydraulic nonlinearity in redundantly actuated shaking tables by proposing a displacement-force dual-loop cooperative control strategy integrated with an adaptive Fuzzy PID algorithm. Through theoretical modeling, simulation, and experimental validation on a 3 × 3 m physical prototype, the following conclusions are drawn:

1. Quantitative Performance Enhancement: The proposed dual-loop strategy significantly improves waveform fidelity. Experimental results under resonance conditions (10 Hz) demonstrate that the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of the acceleration waveform is reduced from 15.2% (single-loop) to 3.2% (dual-loop), satisfying the strict engineering criterion (THD < 10%).

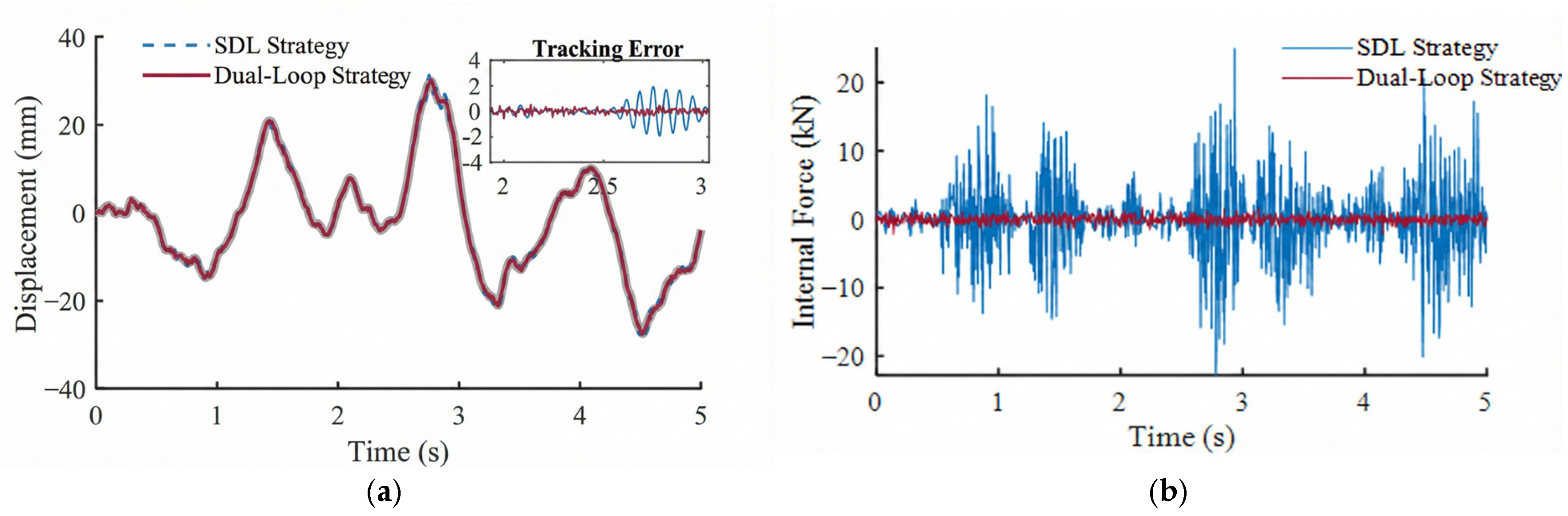

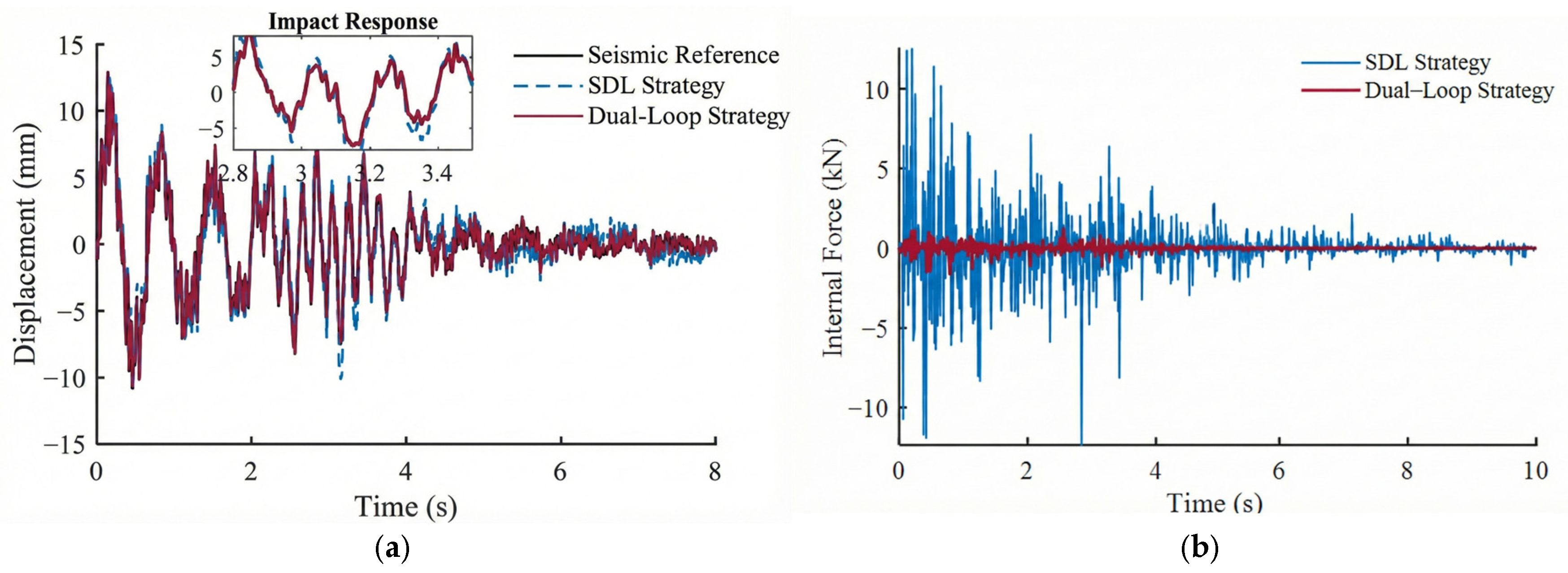

2. Effective Internal Force Suppression: The force balance loop successfully resolves the geometric over-constraints. Under random excitation, the internal force fluctuation amplitude was suppressed by over 87% (from 4.5 kN to 0.58 kN), effectively protecting the mechanism from fatigue damage while maintaining a displacement tracking error as low as 0.22 mm.

3. Robustness via Fuzzy Logic: Compared to linear PID, the fuzzy gain scheduling mechanism provides superior adaptability. Step response tests confirmed that the overshoot was suppressed to less than 5%, validating the controller’s ability to compensate for time-varying hydraulic parameters.

Notwithstanding these achievements, the method presents certain limitations. The current fuzzy inference rules are constructed based on expert experience, which introduces a degree of subjectivity and may not be optimal for all varying operating conditions. Additionally, the bandwidth of the force loop is inherently constrained by the hydraulic response speed. Consequently, future research will focus on integrating data-driven techniques, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), to automate the tuning of control parameters and model complex force-structure interactions more accurately. Further validation will also be extended to near-fault seismic excitations with impulsive pulses to test the system’s transient limits under extreme conditions.