Nano–Micronutrients of Iron and Copper for Improved Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanisms of Nano–Micronutrient Delivery

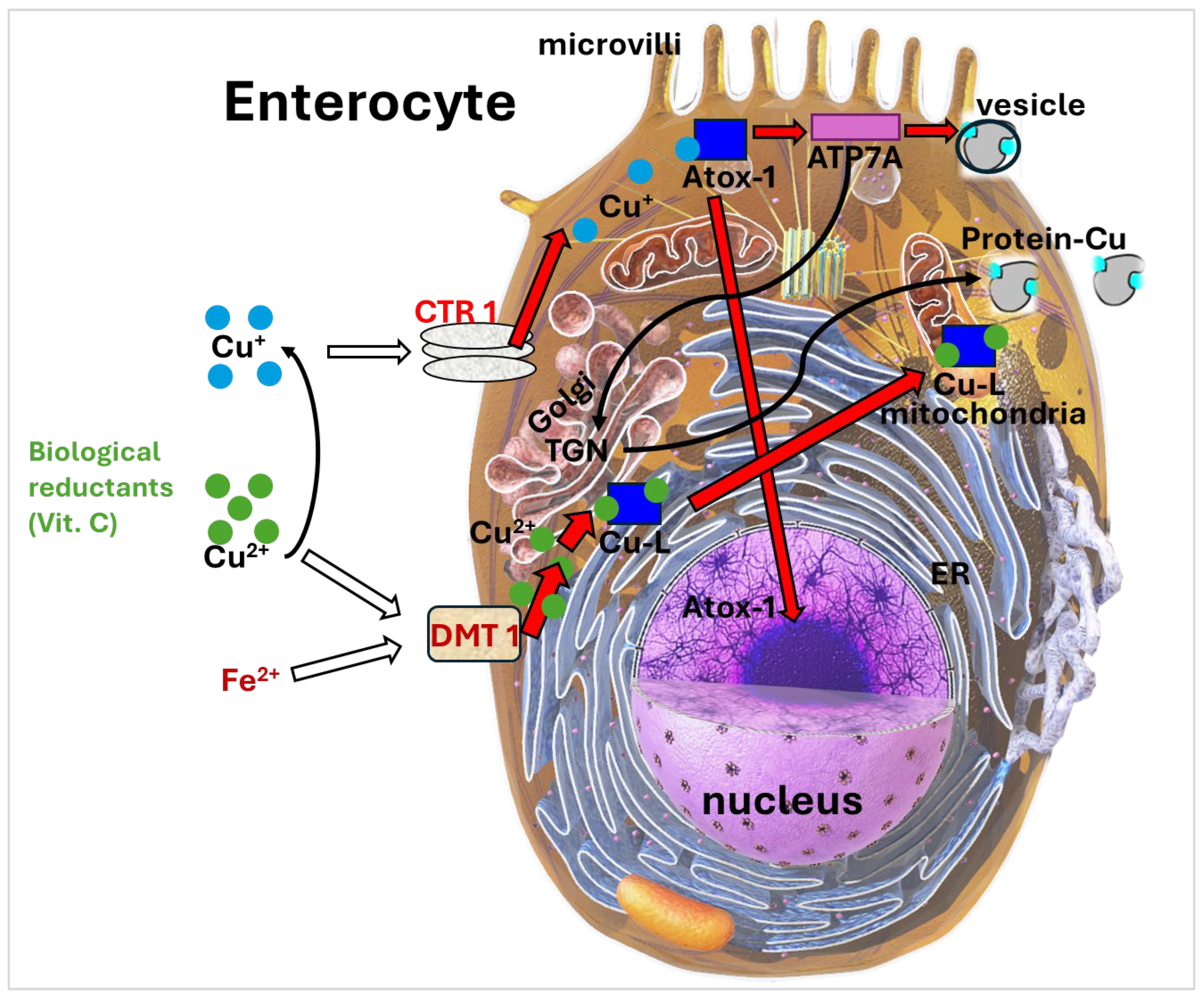

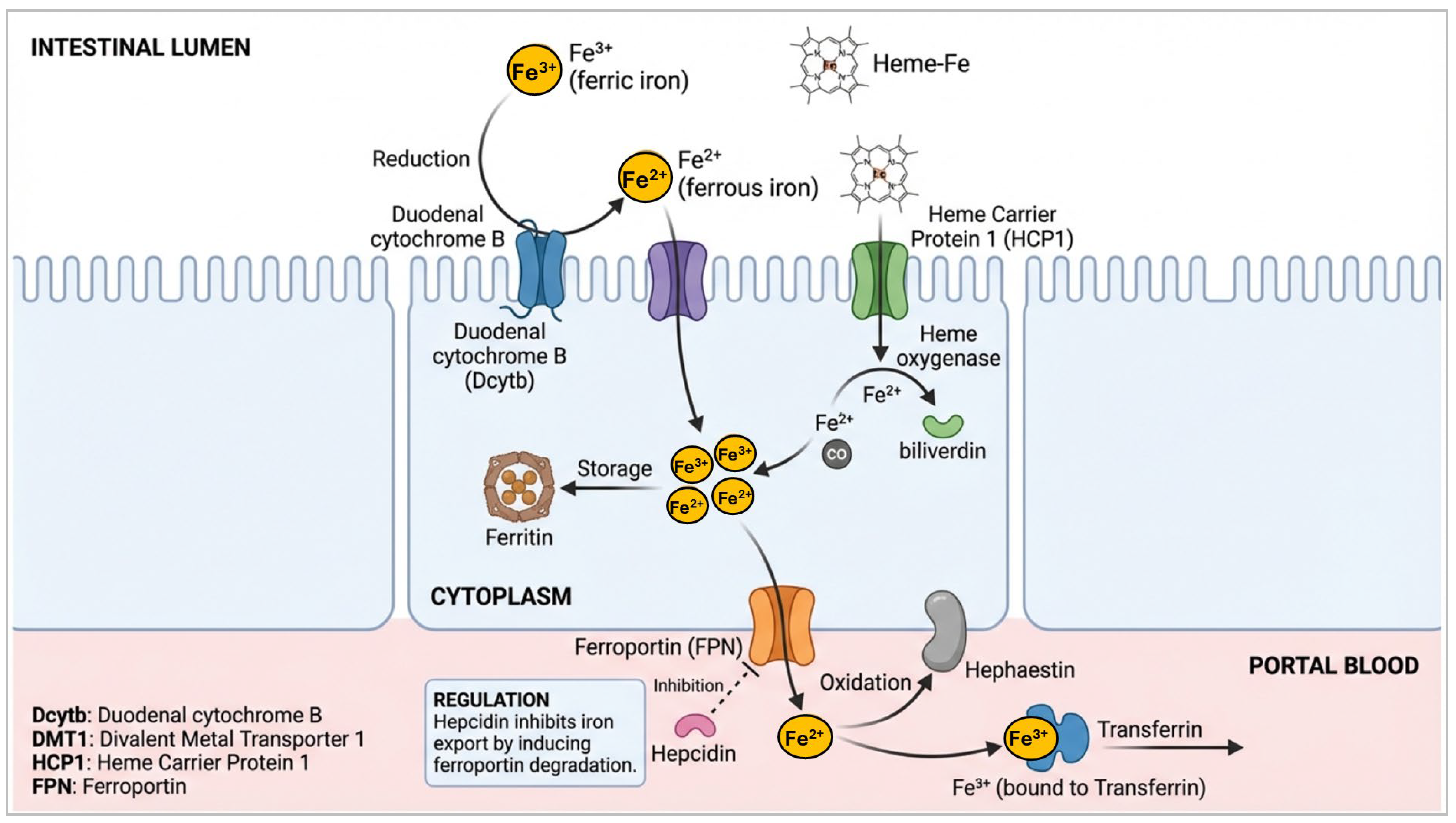

Mechanistic Insights into Iron and Copper Absorption

3. Benefits of Nano–Micronutrients for Human Nutrition

4. Challenges and Limitations

5. Public Health Implications

6. Future Outlook

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nogueira-de-Almeida, C.A.; Prozorovscaia, D.; Mosquera, E.M.B.; Ued, F.d.V.; Campos, V.C. Low bioavailability of dietary iron among Brazilian children: Study in a representative sample from the Northeast, Southeast, and South regions. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1122363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, A.E.; Moretti, D. The importance of iron status for young children in low- and middle-income countries: A narrative review. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Romaña, D.L.; Mildon, A.; Golan, J.; Jefferds, M.E.D.; Rogers, L.M.; Arabi, M. Review of intervention products for use in the prevention and control of anemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2023, 1529, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunuwar, D.R.; Sangroula, R.K.; Shakya, N.S.; Yadav, R.; Chaudhary, N.K.; Pradhan, P.M.S. Effect of nutrition education on hemoglobin level in pregnant women: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazgaj, R.; Lipiński, P.; Szudzik, M.; Jończy, A.; Kopeć, Z.; Stankiewicz, A.M.; Kamyczek, M.; Swinkels, D.; Żelazowska, B.; Starzyński, R.R. Comparative evaluation of sucrosomial iron and iron oxide nanoparticles as oral supplements in iron deficiency anemia in piglets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tako, E. Dietary trace minerals. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschke, R. Copper, iron, cadmium, and arsenic, All generated in the universe: Elucidating their environmental impact risk on human health including clinical liver injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Arcot, J. Fortification of foods with nano-iron: Its uptake and potential toxicity: Current evidence, controversies, and research gaps. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1974–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather-Tait, S. The role of meat in iron nutrition of vulnerable groups of the UK population. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1142252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.B.; Farag, H.A.M.; Salih, T.H.; Awlqadr, F.H.; Al-Manhel, A.J.A.; Vieira, I.R.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Application of nanoparticles in human nutrition: A review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Chauhan, A.K. Iron nanoparticles as a promising compound for food fortification in iron deficiency anemia: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 59, 3319–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Gowachirapant, S.; Zeder, C.; Wieczorek, A.; Guth, J.N.; Kutzli, I.; Siol, S.; von Meyenn, F.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Mezzenga, R. Oat protein nanofibril–iron hybrids offer a stable, high-absorption iron delivery platform for iron fortification. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, S.; Singh, S. Nanominerals packaged in pH-responsive alginate microcapsules exhibit selective delivery in small intestine and enhanced absorption and bioavailability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2408043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, M.E.; Esfandi, R.; Tsopmo, A. Potential of food hydrolyzed proteins and peptides to chelate iron or calcium and enhance their absorption. Foods 2018, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, A.; Leng, J.; Yang, R.; Zhao, W. Preparation of a novel and stable iron fortifier: Self-assembled iron-whey protein isolate fibrils nanocomposites. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 4296–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, O.; Lafazanis, K.; Mourdikoudis, S.; Vourlias, G.; Lialiaris, T.; Pantazaki, A.; Dendrinou-Samara, C. Biological relevance of CuFeO2 nanoparticles: Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity, genotoxicity, DNA and protein interactions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Puniya, A.K.; Dhewa, T. Enhancing micronutrients bioavailability through fermentation of plant-based foods: A concise review. Fermentation 2021, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glahn, R.; Tako, E.; Gore, M.A. The germ fraction inhibits iron bioavailability of maize: Identification of an approach to enhance maize nutritional quality via processing and breeding. Nutrients 2019, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, H.; Woods, P.; Green, B.D.; Nugent, A.P. Can sprouting reduce phytate and improve the nutritional composition and their bioaccessibility in cereals and legumes? Nutr. Bull. 2022, 47, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Polyphenols as plant-based nutraceuticals: Health effects, encapsulation, nano-delivery, and application. Foods 2022, 11, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, Z.W.; Oo, T.H.; Thein, K.Z.; Tun, A.M.; Saeed, H. Copper deficiency anemia: Review article. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altarelli, M.; Ben-Hamouda, N.; Schneider, A.; Berger, M.M. Copper deficiency: Causes, manifestations, and treatment. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.; Yacoubian, C.; Watson, N.; Morrison, I. The risk of copper deficiency in patients prescribed zinc supplements. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 68, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churio, O.; Durán, E.; Guzmán-Pino, S.A.; Valenzuela, C. Use of encapsulation technology to improve the efficiency of an iron oral supplement to prevent anemia in suckling pigs. Animals 2018, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, C.; Lagos, G.; Figueroa, J.; Tadich, T. Behavior of suckling pigs supplemented with an encapsulated iron oral formula. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 13, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.S.; Jones, C.P.; McBride, K.E.; Fritz, E.A.P.; Hirsch, J.; German, J.B.; Siegel, J.B. Acid-active proteases to optimize dietary protein digestibility: A step towards sustainable nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1291685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhu, L.; Qiao, S.; Song, L.; Zhang, M.; Xue, T.; Lv, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Preparation, characterization, and bioavailability evaluation of antioxidant phosvitin peptide-ferrous complex. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 104, 3090–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiełbik, P.; Jończy, A.; Kaszewski, J.; Gralak, M.; Rosowska, J.; Sapierzyński, R.; Witkowski, B.; Wachnicki, Ł.; Lawniczak-Jablonska, K.; Kuzmiuk, P.; et al. Biodegradable zinc oxide nanoparticles doped with iron as carriers of exogenous iron in the living organism. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, I.; Sarbadhikary, P.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Metal-based nanoplatforms for enhancing the biomedical applications of berberine: Current progress and future directions. Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, D.; Goede, J.S.; Zeder, C.; Jiskra, M.; Chatzinakou, V.; Tjalsma, H.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Brittenham, G.; Swinkels, D.W.; Zimmermann, M.B. Oral iron supplements increase hepcidin and decrease iron absorption from daily or twice-daily doses in iron-depleted young women. Blood 2015, 126, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Tan, G.; Shi, R.; Chen, D.; Qin, Y.; Han, J. In vitro bioaccessibility of inorganic and organic copper in different diets. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.; Yoon, S.Y.; ul-Haq, A.; Jo, S.; Kim, S.; Rahim, M.A.; Park, H.A.; Ghorbanian, F.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, M.Y.; et al. The effects of iron deficiency on the gut microbiota in women of childbearing age. Nutrients 2023, 15, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohaska, J. Role of copper transporters in copper homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 826S–829S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, L.M.; Libedinsky, A.; Elorza, A.A. Role of copper on mitochondrial function and metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 711227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, M.; Muñoz, P.; Mura, C.; Núñez, M. DMT1, a physiologically relevant apical Cu1+ transporter of intestinal cells. AJP Cell Physiol. 2003, 284, C1525–C1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; He, J. Cuproptosis: Mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Makova, M.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Essential metals in health and disease. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.; Mar, D.; Ishida, M.; Vargas, R.; Gaite, M.; Montgomery, A.; Linder, M.C. Mechanism of copper uptake from blood plasma ceruloplasmin by mammalian cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashino, T.; Varadarajan, S.; Urao, N.; Oshikawa, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Huo, Y.; Finney, L.; Vogt, S.; McKinney, R.D.; et al. Unexpected role of the copper transporter ATP7A in PDGF-induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Copper trafficking systems in cells: Insights into coordination chemistry and toxicity. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 15277–15296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Xu, K.; Wang, G.; Zhang, F. Copper homeostasis and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 20, 3124–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Collins, J. Transcriptional regulation of the Menkes copper ATPase (Atp7a) gene by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF2α) in intestinal epithelial cells. AJP Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C1298–C1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsenko, S.; Barnes, N.; Bartee, M.; Dmitriev, O. Function and regulation of human copper-transporting ATPases. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 1011–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimnicka, A.; Ivy, K.; Kaplan, J. Acquisition of dietary copper: A role for anion transporters in intestinal apical copper uptake. AJP Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C588–C599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; Lutsenko, S. Copper Transport in Mammalian Cells: Special Care for a Metal with Special Needs. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 25461–25465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Cheng, M.; Yang, R.; Li, H.; Lu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Feng, J.; Tu, L. Research Progress on the Mechanism of Nanoparticles Crossing the Intestinal Epithelial Cell Membrane. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midander, K.; Cronholm, P.; Karlsson, H.; Elihn, K.; Möller, L.; Leygraf, C.; Wallinder, I.O. Surface Characteristics, Copper Release, and Toxicity of Nano- and Micrometer-Sized Copper and Copper(II) Oxide Particles: A Cross-Disciplinary Study. Small 2009, 5, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Qi, J.; Gogoi, R.; Wong, J.; Mitragotri, S. Role of nanoparticle size, shape and surface chemistry in oral drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2016, 238, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapnir, R. Copper absorption and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 1054S–1060S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemhild, K.; Maltzahn, F.; Weiskirchen, R.; Knüchel, R.; Stillfried, S.; Lammers, T. Iron metabolism: Pathophysiology and pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu, P.T.; Heiskala, M.; Peterson, P.A.; Yang, Y. The roles of iron in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2001, 2, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, S.; Haile, D. A novel mammalian iron-regulated protein involved in intracellular iron metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 19906–19912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Yu, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, M. The effect of psychological stress on iron absorption in rats. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashchenko, G.; MacGillivray, R. Multi-copper oxidases and human iron metabolism. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2289–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldvogel-Abramowski, S.; Waeber, G.; Gassner, C.; Buser, A.; Frey, B.M.; Favrat, B.; Tissot, J.-D. Physiology of iron metabolism. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2014, 41, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, A.; Lima, C.; Pinkus, J.; Pinkus, G.; Zon, L.; Robine, S.; Andrews, N. The iron exporter ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis. Cell Metabol. 2005, 1, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonne-Hergaux, F.; Zhang, A.; Ponka, P.; Gros, P. Characterization of the iron transporter DMT1 (NRAMP2/DCT1) in red blood cells of normal and anemic mk/mkmice. Blood 2001, 98, 3823–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edison, E.; Bajel, A.; Chandy, M. Iron homeostasis: New players, newer insights. Eur. J. Haematol. 2008, 81, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.H.; Oates, P.S. Mechanisms and regulation of intestinal iron absorption. Blood Cells Mole. Dis. 2002, 29, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittenham, G.; Weiß, G.; Brissot, P.; Lainé, F.; Guillygomarc’h, A.; Guyader, D.; Moirand, R.; Deugnier, Y. Clinical consequences of new insights in the pathophysiology of disorders of iron and heme metabolism. ASH Educ. Program Book 2000, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadini, P.; Biasiotto, G.; Poli, M.; Levi, S.; Verardi, R.; Zanella, I.; Derosas, M.; Ingrassia, R.; Corrado, M.; Arosio, P. RNA silencing of the mitochondrial ABCB7 transporter in HeLa cells causes an iron-deficient phenotype with mitochondrial iron overload. Blood 2006, 109, 3552–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Gerdtzen, Z.; Núñez, M.; Salgado, J. Mathematical modeling of the relocation of the divalent metal transporter DMT1 in the intestinal iron absorption process. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ignatyeva, N.; Xu, H.; Wali, R.; Toischer, K.; Brandenburg, S.; Lenz, C.; Pronto, J.; Fakuade, F.E.; Sossalla, S.; et al. An alternative mechanism of subcellular iron uptake deficiency in cardiomyocytes. Circul. Res. 2023, 133, E19–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zariwala, M.; Somavarapu, S.; Farnaud, S.; Renshaw, D. Comparison study of oral iron preparations using a human intestinal model. Sci. Pharm. 2013, 81, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.; Bruggraber, S.; Faria, N.; Poots, L.; Tagmount, M.; Aslam, M.; Frazer, D.M.; Vulpe, C.D.; Anderson, G.J.; Powell, J.J. Nanoparticulate iron(III) oxo-hydroxide delivers safe iron that is well absorbed and utilised in humans. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2014, 10, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Liu, D.; Qin, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, P. Mucoadhesive-to-mucopenetrating nanoparticles for mucosal drug delivery: A mini review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settles, M.; Etzrodt, M.; Kosanke, K.; Schiemann, M.; Zimmermann, A.; Meier, R.; Braren, R.; Huber, A.; Rummeny, E.J.; Weissleder, R.; et al. Different capacity of monocyte subsets to phagocytose iron-oxide nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.; Bonaterra, G.; Rudelius, M.; Settles, M.; Rummeny, E.; Daldrup-Link, H. Capacity of human monocytes to phagocytose approved iron oxide MR contrast agents in vitro. Eur. Radiol. 2004, 14, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, N.; Sun, C.; Fichtenholtz, A.; Gunn, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, M. Methotrexate-immobilized poly(ethylene glycol) magnetic nanoparticles for MR imaging and drug delivery. Small 2006, 2, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Z.; Kou, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhu, H.; Tian, J. Comparative transcriptomics revealed neurodevelopmental impairments and ferroptosis induced by extremely small iron oxide nanoparticles. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1402771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramani, C.; Newehy, A.; Alsaif, M.; Al-Numair, K. Vitamin A- and C-rich Pouteria camito fruit derived superparamagnetic nanoparticles synthesis, characterization, and their cytotoxicity. African Health Sci. 2022, 22, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.-U.; Huma, N.; Tarar, O.M.; Shah, W.H. Efficacy of non-heme iron fortified diets: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Hernández, H.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Nano-biofortifying crops with micronutrients and beneficial elements: Toward improved global nutrition. Food Biosci. 2025, 69, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Gulshad, L.; Haq, I.U.; Farooq, M.A.; Al-Farga, A.; Siddique, R.; Manzoor, M.F.; Karrar, E. Nanotechnology: A novel tool to enhance the bioavailability of micronutrients. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 3354–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Song, C.; Wu, T. Effects of nano-copper on antioxidant function in copper-deprived Guizhou black goats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 2201–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szudzik, M.; Starzyński, R.R.; Jończy, A.; Mazgaj, R.; Lenartowicz, M.; Lipiński, P. Iron supplementation in suckling piglets: An ostensibly easy therapy of neonatal iron deficiency anemia. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberal, Â.; Pinela, J.; Vívar-Quintana, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L. Fighting iron-deficiency anemia: Innovations in food fortificants and biofortification strategies. Foods 2020, 9, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanog, A.D.; Calayugan, M.I.C.; Descalsota-Empleo, G.I.; Amparado, A.; Inabangan-Asilo, M.A.; Arocena, E.C.; Sta Cruz, P.C.; Borromeo, T.H.; Lalusin, A.; Hernandez, J.E.; et al. Zinc and iron nutrition status in the Philippines population and local soils. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Venter, C.; Roth-Walter, F. Malnutrition and allergies: Tipping the immune balance towards health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, B.L.; Thakur, S.S.; Goutam, P.K.; Prajapati, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Kumar, A. The role of bio-fortification in enhancing the nutritional quality of vegetables: A review. Adv. Res. 2024, 25, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connorton, J.M.; Balk, J. Iron biofortification of staple crops: Lessons and challenges in plant genetics. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.; Boy, E.; Wirth, J.P.; Hurrell, R.F. Review: The potential of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) as a vehicle for iron biofortification. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1144–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Golestan, L.; Baei, M.S. Studying the enrichment of ice cream with alginate nanoparticles including Fe and Zn salts. J. Nanopart. 2013, 2013, 754385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razack, S.A.; Suresh, A.; Sriram, S.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Sadanandham, S.; Veerasamy, M.; Nagalamadaka, R.B.; Sahadevan, R. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Hibiscus rosa-sinensis for fortifying wheat biscuits. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewińska, E.; Ognik, K.; Fotschki, B.; Zduńczyk, Z.; Juśkiewicz, J. Comparison of the effect of dietary copper nanoparticles and one copper (II) salt on the copper biodistribution and gastrointestinal and hepatic morphology and function in a rat model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzec, A.; Cholewińska, E.; Fotschki, B.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Ognik, K. Inulin improves the redox response in rats fed a diet containing recommended copper nanoparticle (CuNPs) levels, while pectin or psyllium in rats receive excessive CuNPs levels in the diet. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasco, J.; Anderson, K.; Williams, L.; Stuart, A.; Hyde, N.; Holloway-Kew, K. Dietary intakes of copper and selenium in association with bone mineral density. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, X.; He, P.; Zhou, C.; Zu, C.; Meng, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.; et al. J-shaped association between dietary copper intake and all-cause mortality: A prospective cohort study in Chinese adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 129, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbik, P.; Kaszewski, J.; Dominiak, B.; Damentko, M.; Serafińska, I.; Rosowska, J.; Gralak, M.A.; Krajewski, M.; Witkowski, B.S.; Gajewski, Z.; et al. Preliminary Studies on Biodegradable Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Doped with Fe as a Potential Form of Iron Delivery to the Living Organism. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, A.; Okebe, J.; Yahav, D.; Paul, M. Oral iron supplements for children in malaria-endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD006589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Y.; Gabay, E.; Božić, D.; Shibli, J.A.; Ginesin, O.; Asbi, T.; Takakura, L.; Mayer, Y. The Impact of Nutritional Components on Periodontal Health: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, I.; Farinha, C.; Barreto, P.; Coimbra, R.; Pereira, P.; Marques, J.P.; Pires, I.; Cachulo, M.L.; Silva, R. Nutritional Genomics: Implications for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkundabombi, M.G.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Muyonga, J.H. Effect of processing methods on nutritional, sensory, and physicochemical characteristics of biofortified bean flour. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, S.A.; Ömür, A.D. Nanoparticles as food additives and their possible effects on male reproductive systems. In Nanotechnology in Reproduction; Öztürk, A.E., Ed.; Özgür Publications: Istanbul, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Gong, P.; Su, P.; Fan, L.; Li, G. Emerging nanoparticles in food: Sources, application, and safety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 3564–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognik, K.; Stępniowska, A.; Cholewińska, E.; Kozłowski, K. The effect of administration of copper nanoparticles to chickens in drinking water on estimated intestinal absorption of iron, zinc, and calcium. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroczek-Sosnowska, N.; Sawosz, E.; Vadalasetty, K.P.; Łukasiewicz, M.; Niemiec, J.; Wierzbicki, M.; Kutwin, M.; Jaworski, S.; Chwalibog, A. Nanoparticles of copper stimulate angiogenesis at systemic and molecular level. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 4838–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaningini, A.G.; Nelwamondo, A.M.; Azizi, S.; Maaza, M.; Mohale, K.C. Metal nanoparticles in agriculture: A review of possible use. Coatings 2022, 12, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameli, K.; Ahmad, M.; Zamanian, A.; Sangpour, P.; Parvaneh Shabanzadeh, P.; Abdollahi, Y.; Mohsen, Z. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Curcuma longa tuber powder. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 5603–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftel, J.; Loechl, C.; Mokhtar, N.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Use of stable isotopes to evaluate bioefficacy of provitamin A carotenoids, vitamin A status, and bioavailability of iron and zinc. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Georgieff, M.K.; Brittenham, G.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Hurrell, R.F.; McArdle, H.J.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of nutrition for development (BOND)—Iron review. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1001S–1067S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymlek-Gay, E.A.; Rooney, H.; Ordner, J.; Atkins, L.A. Dietary iron bioavailability in premenopausal Australian women. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2025, 84, E103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białowąs, W.; Blicharska, E.; Drabik, K. Biofortification of plant- and animal-based foods in limiting the problem of microelement deficiencies—A narrative review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peroni, D.G.; Hufnagl, K.; Comberiati, P.; Roth-Walter, F. Lack of iron, zinc, and vitamins as a contributor to the etiology of atopic diseases. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1032481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, C.; Kodama, H.; Sato, Y.; Mimaki, M.; Yagi, M.; Awano, H.; Matsuo, M.; Shintaku, H.; Yoshida, S.; Takayanagi, M.; et al. Early clinical signs and treatment of Menkes disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2022, 31, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; Mangan, D.; O’Keefe, J.H. Copper deficiency may be a leading cause of ischaemic heart disease. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevay, L.M. IHD from copper deficiency: A unified theory. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Weber, R.; Buckley, A.; Mazzolini, J.; Robertson, S.; Delgado-Saborit, J.; Rappoport, J.Z.; Warren, J.; Hodgson, A.; Sanderson, P.; et al. Environmentally relevant iron oxide nanoparticles produce limited acute pulmonary effects in rats at realistic exposure levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, M.; Luo, J.; Zhao, L.; Ye, G.; Shi, F.; Lv, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Liver toxicity assessments in rats following sub-chronic oral exposure to copper nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youness, E.; Arafa, A.; Aly, H.; EL-Meligy, E. Therapeutic potential of quercetin on biochemical deteriorations induced by copper oxide nanoparticles. Asian J. Res. Biochem. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, L.; Laing, E.; Peake, J.; Uyeminami, D.; Mack, S.; Li, X.; Smiley-Jewell, S.; Pinkerton, K.E. Repeated iron–soot exposure and nose-to-brain transport of inhaled ultrafine particles. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 46, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lei, C.; Shen, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Guo, M.; Huang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Yao, S. Analysis of copper nanoparticles toxicity based on a stress-responsive bacterial biosensor array. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharsana, U.; Varsha, M.; Behlol, A.; Veerappan, A.; Raman, T. Sulfidation modulates the toxicity of biogenic copper nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30248–30259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bussche, A.; Kabadi, P.; Kane, A.; Hurt, R. Biological and environmental transformations of copper-based nanomaterials. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 8715–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, V.; Spitzmiller, M.; Hong-Hermesdorf, A.; Kropat, J.; Damoiseaux, R.; Merchant, S.; Mahendra, S. Copper status of exposed microorganisms influences susceptibility to metallic nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 35, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffitt, R.; Luo, J.; Gao, J.; Bonzongo, J.; Barber, D. Effects of particle composition and species on toxicity of metallic nanomaterials in aquatic organisms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1972–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.; Pinheiro, J.; Cancio, I.; Pereira, C.; Cardoso, C.; Bebianno, M. Effects of copper nanoparticles exposure in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9356–9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unrine, J.; Tsyusko, O.; Murph, S.; Judy, J.; Bertsch, P. Effects of particle size on chemical speciation and bioavailability of copper to earthworms (Eisenia fetida) exposed to copper nanoparticles. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1942–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffitt, R.; Weil, R.; Hyndman, K.; Denslow, N.; Powers, K.; Taylor, D.; Barber, D.S. Exposure to copper nanoparticles causes gill injury and acute lethality in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 8178–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa-Sanzana, S.; Moya-Osorio, J.; Morejón Terán, Y.; Ríos-Castillo, I.; Becerra Granados, L.M.; Prada Gómez, G.; Ramos de Ixtacuy, M.; Fernández Condori, R.C.; Nessier, M.C.; Guerrero Gómez, A.; et al. Food insecurity and sociodemographic factors in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. PAJPH 2024, 48, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceddia, M.G. The impact of income, land, and wealth inequality on agricultural expansion in Latin America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2527–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO New UN Report: 74 Percent of Latin American and Caribbean Countries Are Highly Exposed to Extreme Weather Events, Affecting Food Security. FAO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/new-un-report--74-percent-of-latin-american-and-caribbean-countries-are-highly-exposed-to-extreme-weather-events--affecting-food-security/en (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Villegas, E.; Hammons, A.J.; Wiley, A.R.; Fiese, B.H.; Teran-Garcia, M. Cultural Influences on Family Mealtime Routines in Mexico: Focus Group Study with Mexican Mothers. Children 2022, 9, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, M.; Talsma, E.F.; Taleon, V.; Londoño, L.; Brychkova, G.; Gallego, S.; Raatz, B.; Spillane, C. Iron, Zinc and phytic acid retention of biofortified, low phytic acid, and conventional bean varieties when preparing common household recipes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, L.J.; Monteiro, A.; Piñon, A. Recent advances in understanding the influence of zinc, copper, and manganese on the gastrointestinal environment of pigs and poultry. Animals 2021, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, I.; Taarji, N.; Johnson, P.N.T.; Barrett, J.; Cairncross, C.; Rush, E. Plant-based food by-products: Prospects for valorisation in functional bread development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazan, R.; Maillot, M.; Reboul, E.; Darmon, N. Pulses twice a week in replacement of meat modestly increases diet sustainability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh Ra Singh Ri Singh, P.K.; Shivangi Singh, O. Climate smart foods: Nutritional composition and health benefits of millets. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, J.L.; Marshall, R.; McCormick, R.; Truong, S.K.; Styles, D.; Gerde, J.A.; Gonzalez-Escobar, E.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Janes-Bassett, V.; Logue, J.; et al. European soybean to benefit people and the environment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Hao, Q.; Zeng, H.; He, Y. Research and progress on the mechanism of iron transfer and accumulation in rice grains. Plants 2021, 10, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics | Study Duration | Characteristics and Dose of Nanoparticles Used | Health Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Wistar rats/group; 5-week-old males | 4 weeks | Cu NP powder; 40–60 nm; 6.5 or 3.25 mg/kg BW | Significant improvement in Cu absorption and distribution; enhanced gastrointestinal health was observed by low dose, whereas high dose caused liver toxicity | Cholewińska et al. [85] |

| 10 Wistar rats/group | 6 weeks | Cu NP combined with fibers (cellulose, pectin, inulin, or psyllium); 40–60 nm; 6.5 or 13 mg/kg BW | Enhanced antioxidant capacity and reduced oxidative stress markers noted in rats consuming Cu NPs with inulin | Marzec et al. [86] |

| 522 Australian women | Cross-sectional | Dietary intake of ionic Cu and Se was assessed independently | Ionic Cu and Se intakes were independently associated with improved bone mineral density, suggesting a role for Cu in bone health | Pasco et al. [87] |

| 17,310 participants | 1997 to 2015, prospective open-cohort study | Dietary intake assessed via survey | Lower cardiovascular risks were associated with moderate ionic Cu intake, highlighting the importance of Cu in overall health | Gan et al. [88] |

| 4 adult mice experimental group and 2 mice control group | 24 h | Biodegradable ZnO: Fe nanoparticles; 10 mg/mL; 0.3 mL/mouse | Enhanced Fe bioavailability and safety; nanoparticles effectively delivered Fe to various body tissues | Kiełbik et al. [89] |

| 31,955 children <18 yr-old; review | 1973–2013 | Standard Fe supplements | Fe supplementation did not result in an excess of severe malaria, and led to fewer anemic children at follow-up | Neuberger et al. [90] |

| Review | NA | Dietary intake of micronutrients such as Fe and Cu was assessed | Supplementation of specific micronutrients such as Fe and Cu may benefit periodontal therapy, although evidence remains inconclusive. | Berg et al. [91] |

| Narrative review | NA | Dietary intake of various supplements, including Cu assessed | Supplements, including Cu, can reduce the progression to advanced age-related macular degeneration | Figueiredo et al. [92] |

| Model Organism | Dose | Chemical Composition & Size | Toxicity/Health Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprague–Dawley rats | nose-only exposure, 50 µg/m3 and 500 µg/m3, 3 h/d × 3 d | FeOxNPs (size not specified) | No clinical signs of toxicity, including no significant changes in transcriptomic or metabolomic responses in lung or BEAS-2B cells, to suggest adverse effects | Guo et al. [108] |

| Sprague–Dawley rats (8-week-old) | 50-200 mg/kg/day via oral gavage | CuNP; 82.5 ± 33.4 nm | Significant hepatic oxidative stress, inflammation, and dose-dependent increases in liver toxicity | Tang et al. [109] |

| Female rats | Intraperitoneal injection of 3 and 50 mg/kg of CuO-NPs for 7 days | CuO-NPs; >20 nm | Induced liver toxicity with diminished PON1 activity; improvement noted with quercetin treatment | Youness et al. [110] |

| Adult female C57B6 mice | 40 μg/m of Fe oxide nanoparticles; 6 h/day, 5 days/week for 5 consecutive weeks | Fe soot (ultrafine particles) | Evidence of neural inflammation and transport to the brain via the olfactory region post-exposure | Hopkins et al. [111] |

| E. coli-based biosensor | NA | CuNP (size not specified) | CuNPs led to H2O2 generation via release of Cu(I) ions, and caused damage to protein, DNA, and cell membrane in E. coli | Li et al. [112] |

| Zebrafish | NA | Biogenic CuNP and CuSNP | Reduced oxidative stress in liver and brain acetylcholinesterase activity of CuNP observed with sulfidation; insights into minimizing adverse effects in biological systems | Dharsana et al. [113] |

| In vitro lung cells | NA | CuNP and CuONP, including micrometer-size Cu particles (size not specified) | Induced a higher degree of DNA damage by nanoparticles compared to micro particles; ion released could not account for the higher toxicity | Midander et al. [47] |

| Murine macrophage cell line (J774.A1) | 5–20 mg/L (ppm) | CuONP and CuSNP; 50 nm, −25 mV | CuONPs induced significantly higher toxicity than CuSNPs after 24 h and 48 h, due to lower Cu bioavailability with CuSNP | Wang et al. [114] |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 20 mg/L | CuNP; 20–50 nm | Rapid aggregation of nanoparticles into micro-sized particles in algal tris-acetate-phosphate medium; CuNPs were less toxic than CuCl2 | Reyes et al. [115] |

| Zebrafish and Daphnia magna | N/A | CuNP (size not specified) | Nanoparticulate forms of metals were less toxic than soluble ions based on mass added; toxicity was lower for zebrafish than D. magna Induced gill injury and lethality; high levels of reactive oxygen species linked to toxicity were demonstrated. | Griffitt et al. [116] |

| Mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) | 10 µg Cu/L; 15 days | CuNP and Cu2+ ions; 31 ± 10 nm, but aggregated in seawater with size of 238 to 338 nm | Significant gill metal accumulation and stress response markers indicating toxic effects were observed for both compounds | Gomes et al. [117] |

| Earthworms (Eisenia fetida) | up to 65 mg/kg soil | CuNP; <100 nm | CuNPs up to 65 mg kg−1 caused no adverse effects on ecologically relevant endpoints, but may be toxic at higher concentrations (>65 mg Cu kg−1 soil) | Unrine et al. [118] |

| Zebrafish | Up to 100 µg/L | CuNP; 80 nm | CuNP led to different morphological effects and gene expression patterns in the gill than soluble Cu | Griffitt et al. [119] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pokhrel, L.R.; Fallah, S.; Garcia, L.C. Nano–Micronutrients of Iron and Copper for Improved Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031478

Pokhrel LR, Fallah S, Garcia LC. Nano–Micronutrients of Iron and Copper for Improved Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031478

Chicago/Turabian StylePokhrel, Lok R., Sina Fallah, and Lauren C. Garcia. 2026. "Nano–Micronutrients of Iron and Copper for Improved Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031478

APA StylePokhrel, L. R., Fallah, S., & Garcia, L. C. (2026). Nano–Micronutrients of Iron and Copper for Improved Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031478