Optimal Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks in Systems with Conventional Generation, Renewable, and Storage Systems Using DC Flows

Abstract

1. Introduction

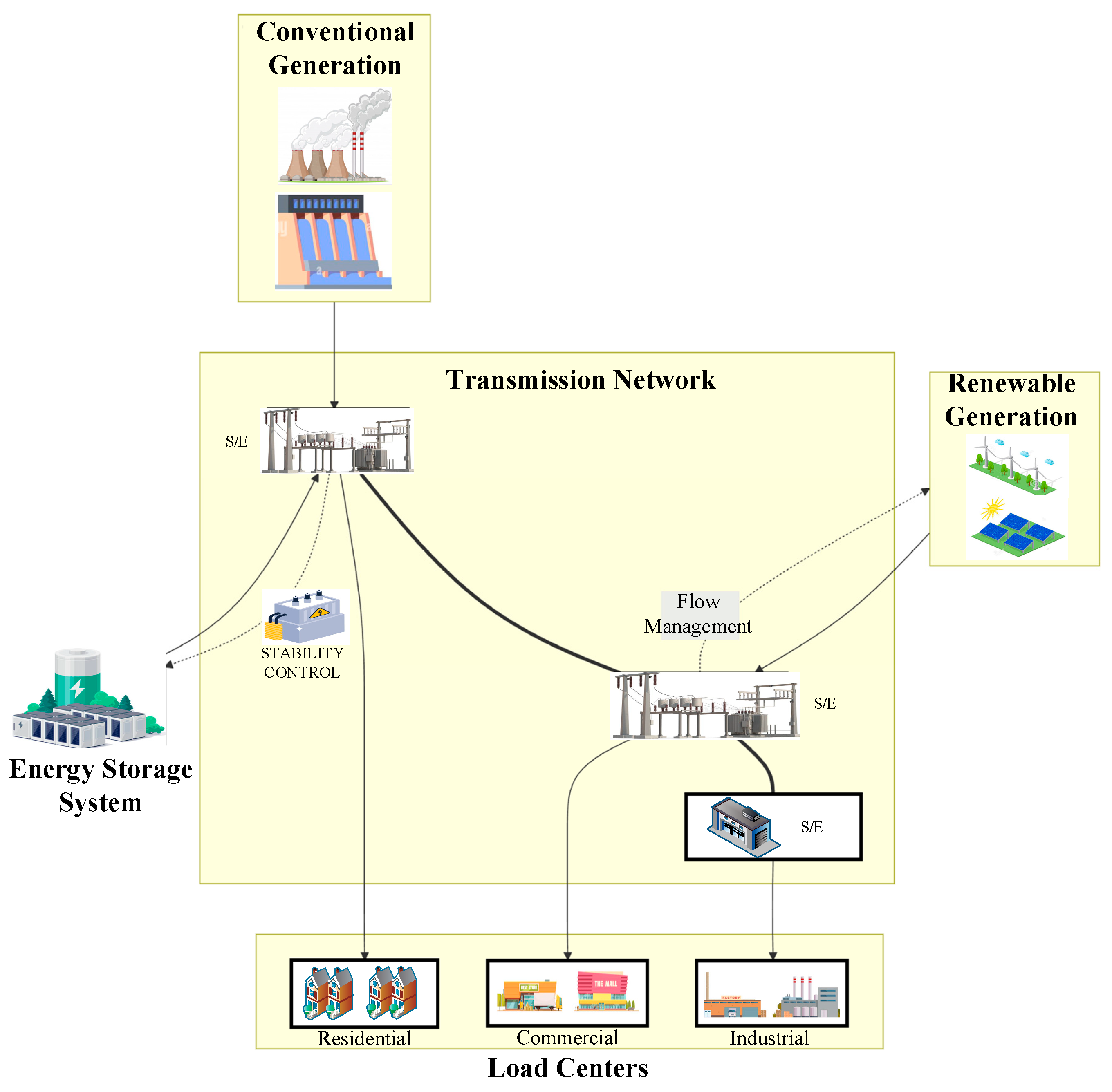

2. Renewable Generation and Storage in Modern Electrical Grids

2.1. Fundamentals of Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks (DEBH)

2.2. Integration of Conventional, Renewable Generation and Energy Storage Systems in the DEBH

3. Problem Statement

3.1. Time-Based Electricity Dispatch Model Using FPDC

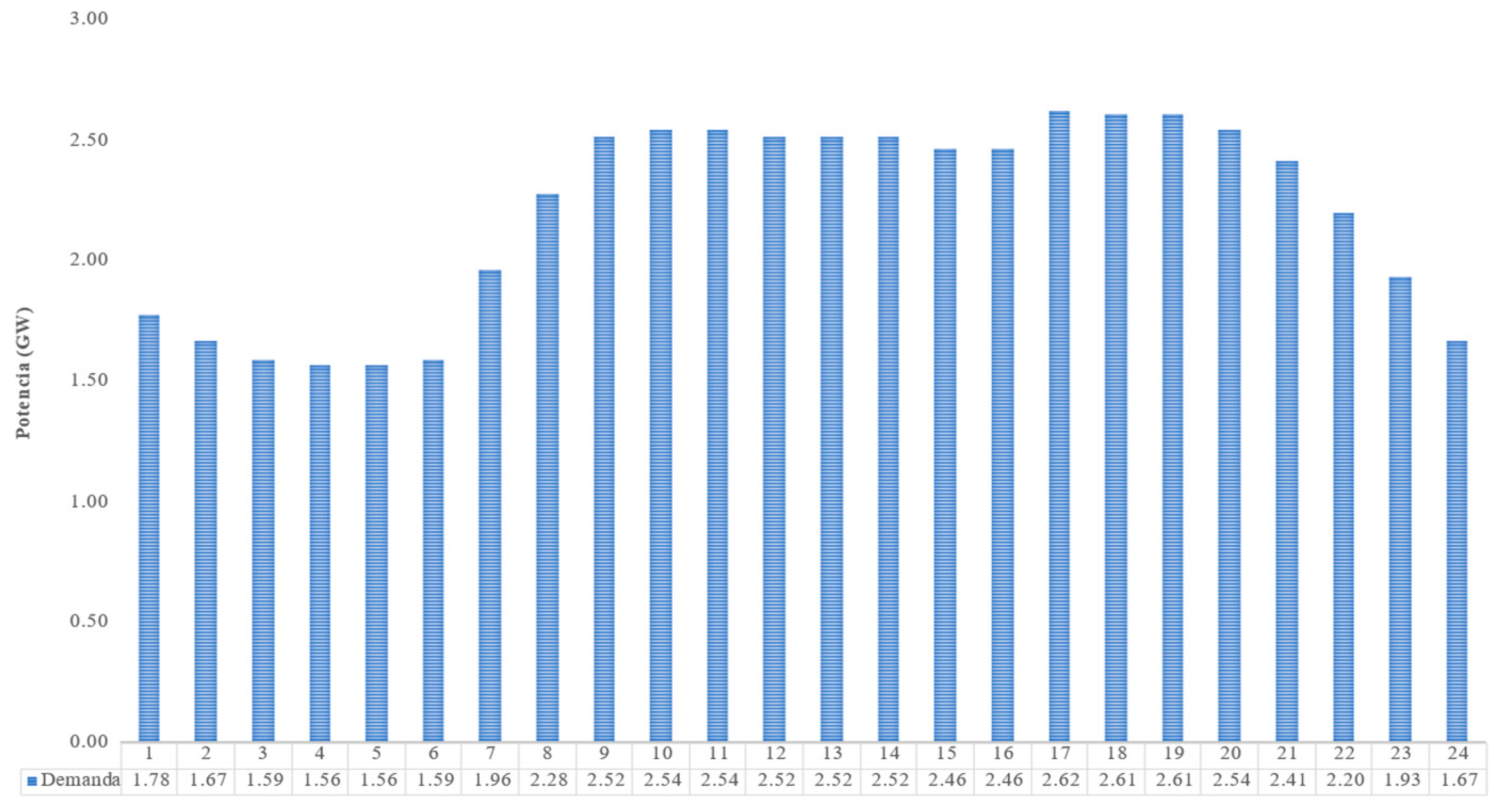

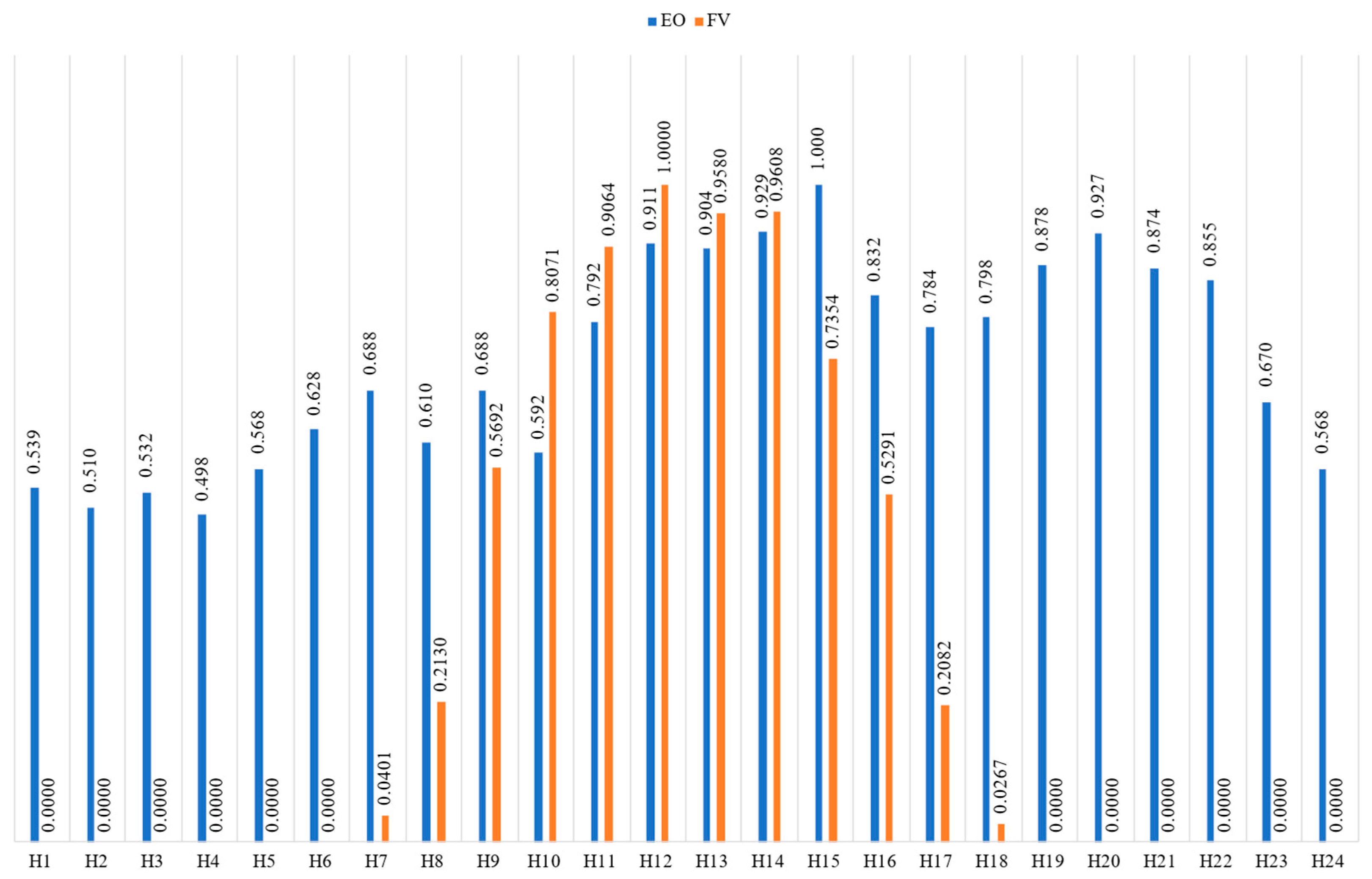

3.2. Characterization of the System Under Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

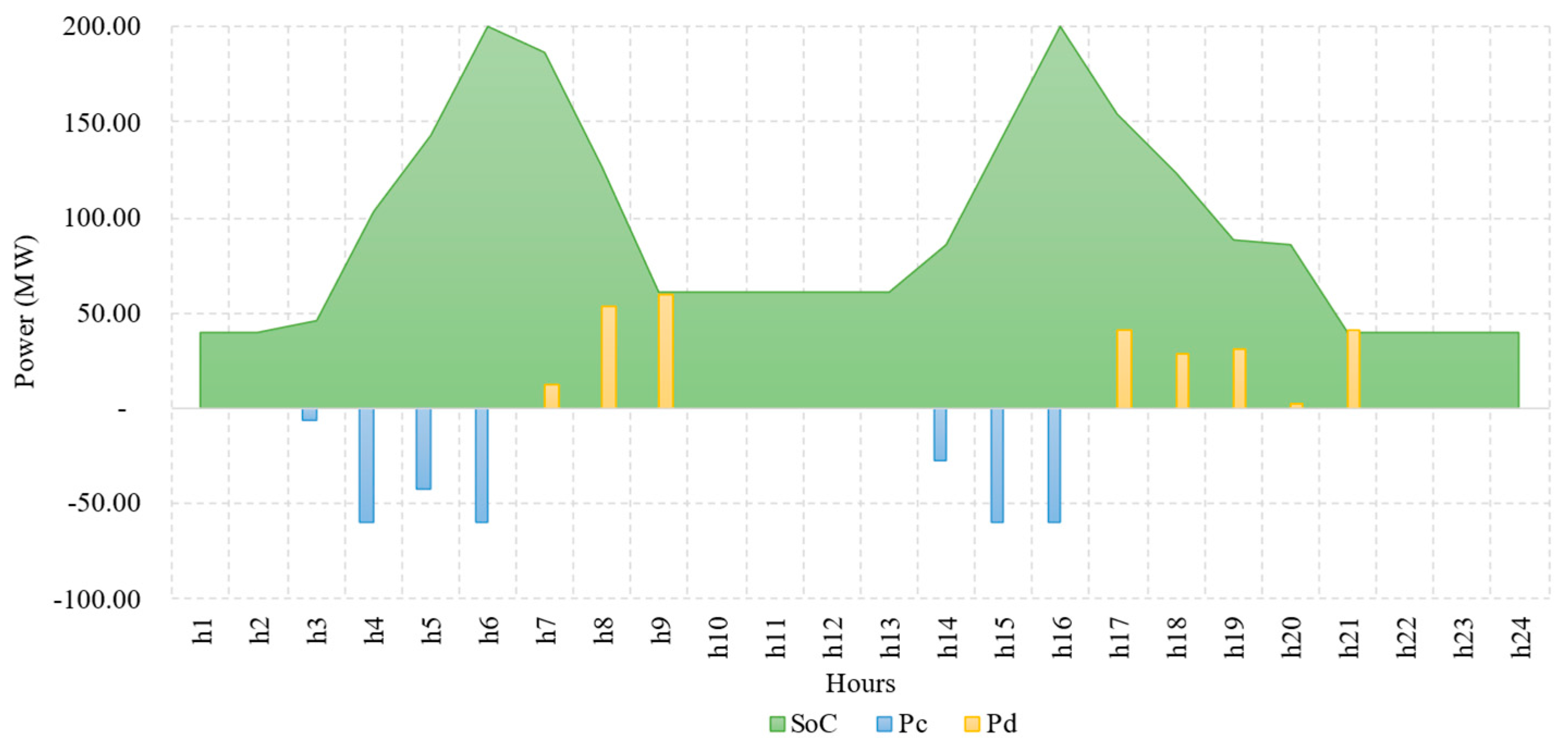

4.1. Energy Analysis

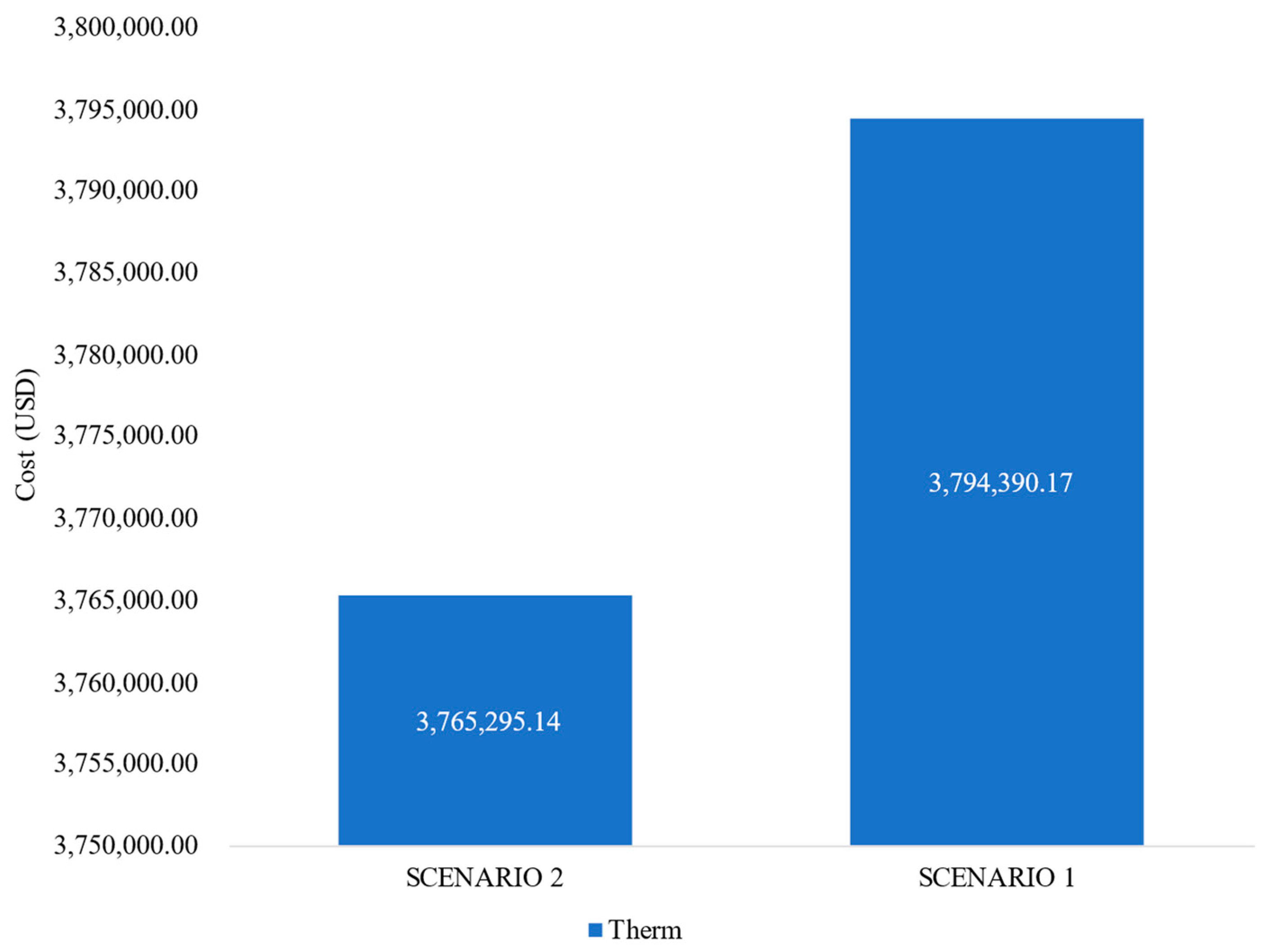

4.2. Economic Analysis

4.3. Peak Demand Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bistline, J.; Blanford, G.; Mai, T.; Merrick, J. Modeling variable renewable energy and storage in the power sector. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapalan, K.; Constant, E. Overview of Energy Storage Technologies for Excess Renewable Energy Production. In Proceedings of the 24th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, Virtual, 13–16 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Laugs, G.A.H.; Benders, R.M.J.; Moll, H.C. Balancing responsibilities: Effects of growth of variable renewable energy, storage, and undue grid interaction. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Korpås, M.; Botterud, A. Power system decarbonization: Impacts of energy storage duration and interannual renewables variability. Renew. Energy 2020, 156, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Du, E.; Zhang, N.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y. Power system planning with high renewable energy penetration considering demand response. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2021, 4, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, Z.; Mei, S.; Catalao, J.P.S. Impact of Energy Storage on Economic Dispatch of Distribution Systems: A Multi-Parametric Linear Programming Approach and its Implications. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2020, 7, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, N.; Hoque, M.E.; Rashid, F.; Aziz, M.; Uddin, M.S.; Islam, T. Effects of dispatch algorithms and fuel variation on techno-economic performance of hybrid energy system in remote island. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 109919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlalele, T.G.; Naidoo, R.M.; Zhang, J.; Bansal, R.C. Dynamic economic dispatch with maximal renewable penetration under renewable obligation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 38794–38808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, B.; Wahbah, M.; Moursi, M.S.E.; El-Fouly, T.H.M. Renewable Energy Management System: Optimum Design and Hourly Dispatch. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Almassalkhi, M. Optimal Corrective Dispatch of Uncertain Virtual Energy Storage Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4155–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, N.; Function, A.O. Economic Dispatch of Distribution Network with Distributed Energy Storage and PV Power Stations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Applied Superconductivity and Electromagnetic Devices (ASEMD), Tianjin, China, 16–18 October 2020; pp. 2020–2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Jian, G. Optimal operation of coordinated multi-carrier energy hubs for integrated electricity and gas networks. Energy 2024, 288, 129800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Mehrtash, M. Optimal operation of a residential energy hub participating in electricity and heat markets. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, M.; Daoud, M.; Khadem, S.K. Optimal dispatch of battery energy storage for multi-service provision in a collocated PV power plant considering battery ageing. Energy 2024, 293, 130744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, S.; Dubey, A. Stochastic Economic Dispatch with Battery Energy Storage considering Wind and Load Uncertainty. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.18100. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, J.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Escudero-Quintero, C.; Guzmán, J.P. Economic and environmental power dispatch for energy management systems applied to microgrids with wind energy resources and battery energy storage systems. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, V.; Dubey, H.M.; Pandit, M.; Salkuti, S.R. Economic Dispatch in Microgrid with Battery Storage System using Wild Geese Algorithm. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2025, 4, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, S.; Pitchumani, R.; Maack, J.; Satkauskas, I.; Reynolds, M.; Jones, W. Stochastic economic dispatch of wind power under uncertainty using clustering-based extreme scenarios. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 229, 110158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Rotella, P., Jr.; Rocha, L.C.S.; Barbosa, A.d.S.; Bolis, I. Optimization methods of distributed hybrid power systems with battery storage system: A systematic review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yan, Y. Economic dispatching problem with group and resource considerations. In Proceedings of the 2012 24th Chinese Control and Decision Conference, CCDC 2012, Taiyuan, China, 23–25 May 2012; pp. 4114–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chung, S.; AlShelahi, A.; Kontar, R.; Byon, E.; Saigal, R. Look-ahead decision making for renewable energy: A dynamic ‘predict and store’ approach. Appl. Energy 2021, 296, 117068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, R.; Oikonomou, K.; Parvania, M. Look-ahead optimal participation of compressed air energy storage in day-ahead and real-time markets. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Park, W.-K.; Lee, I.-W. Economic Dispatch of Multiple Energy Storage Systems Under Different Characteristics. Energy Procedia 2017, 141, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gordon, D.; Scott, P. Receding horizon dispatch of multi-period look-ahead market for energy storage integration. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hu, X.; Chen, C.; Wu, R.; Wu, T.; Huang, H. Research on day-ahead and intraday scheduling strategy of distributed network based on dynamic partitioning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 160, 110078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Yao, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Day-ahead and intra-day optimal dispatching considering the observability and controllability of cyber–physical power grid. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.S.; Nguyen, T.N.; Bui, D.-K.; Ngo, T.D. Optimal sizing of renewable energy storage: A techno-economic analysis of hydrogen, battery and hybrid systems considering degradation and seasonal storage. Appl. Energy 2023, 336, 120817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Barkouki, B.; Laamim, M.; Rochd, A.; Chang, J.-W.; Benazzouz, A.; Ouassaid, M.; Kang, M.; Jeong, H. An economic dispatch for a shared energy storage system using MILP optimization: A case study of a Moroccan microgrid. Energies 2023, 16, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, A.; Hassankashi, A.; Pirouzi, S.; Lehtonen, M.; Arandian, B.; Baziar, A.A. A flexible-reliable operation optimization model of the networked energy hubs with distributed generations, energy storage systems and demand response. Energy 2022, 239, 121923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Asim, M. Advancement, challenges and solutions of PV integrated battery energy storage systems: A review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Shen, H. Optimal dispatch of a novel integrated energy system combined with multi-output organic Rankine cycle and hybrid energy storage. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wei, W. Hybrid energy storage sizing in energy hubs: A continuous spectrum splitting approach. Energy 2024, 300, 131504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggu, M.M.; Nagarajan, A.; Cutler, D.; Olis, D.; Bialek, T.O.; Symko-Davies, M. Coordinated optimization of multiservice dispatch for energy storage systems with degradation model for utility applications. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, M.; Yang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Pandzic, H. Optimal dispatching of an energy system with integrated compressed air energy storage and demand response. Energy 2021, 234, 121232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, T.; Litvinov, E. A multi-period market design for markets with intertemporal constraints. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Molzahn, D.K. Optimizing parameters of the DC power flow. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, H.; Li, S. Distributed dispatch of non-convex integrated electricity and gas systems considering AC power flow and gas dynamics. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 126025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaery, M.; Abouzeid, S.I.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Abido, M.A. Consensus-based economic dispatch for DC microgrids incorporating realistic cyber delays. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 107, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, J.; Cornachione, M.; Li, L.; Schweitzer, E.; Eldridge, B. Modeling distributed energy resource aggregations in security constrained unit commitment and economic dispatch. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 170, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, W.; Lu, P.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Lu, J. Multi-objective optimization and mechanism analysis of integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage system: Based on medium-long-term complementary dispatching model coupled with short-term power balance. Energy 2025, 332, 137246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoudis, C.; Pinson, P.; González, J.M.M.; Zugno, M. An Updated Version of the IEEE RTS 24-Bus System for Electricity Market and Power System Operation Studies; Technical University of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA—International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024. Abu Dhabi, 2024. Available online: www.irena.org (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ralon, P.; Taylor, M.; Ilas, A.; Diaz-Bone, H.; Kairies, K. Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to 2030; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2017; Volume 164, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- CENACE. Annual Report—CENACE 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.cenace.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2025/04/Informe-Anual-CENACE-2024-vf-1-88_c.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- CENACE—National Electricity Operator. Operational Information—CENACE. Available online: https://www.cenace.gob.ec/info-operativa/InformacionOperativa.htm (accessed on 18 September 2025).

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sb | 100 | MVA | Base power of the system |

| VPC | 1533 | USD/MWh | Load loss value |

| H | 24 | hours | Optimization horizon |

| ID | Pmax [MW] | Pmin [MW] | Cost [USD/MWh] | Up [MW/h] | Dw [MW/h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gc1 | 100.00 | 30.40 | 136.64 | 14 | 14 |

| Gc2 | 100.00 | 30.40 | 136.64 | 14 | 14 |

| Gc3 | 300.00 | 75.00 | 200.70 | 49 | 49 |

| Gc4 | 591.00 | 206.85 | 50.93 | 21 | 21 |

| Gc5 | 60.00 | 12.00 | 278.22 | 21 | 21 |

| Gc6 | 100.00 | 54.25 | 167.04 | 7 | 7 |

| Gc7 | 100.00 | 54.25 | 127.04 | 21 | 21 |

| Gc8 | 300.00 | 100.00 | 12.04 | 47 | 47 |

| Gc9 | 300.00 | 100.00 | 10.94 | 47 | 47 |

| Gc10 | 200.00 | 10.00 | 20.26 | 35 | 35 |

| Gc11 | 250.00 | 108.50 | 131.04 | 21 | 21 |

| Gc12 | 250.00 | 140.00 | 129.78 | 28 | 28 |

| ID | Node | Pmax [MW] | Pmin [MW] | Cost [USD/MWh] | Guy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gren1 | i8 | 200.00 | 0.00 | 36.00 | FV |

| Gren2 | i19 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 44.00 | FV |

| Gren3 | i17 | 120.00 | 0.00 | 52.00 | EO |

| Gren4 | i13 | 90.00 | 0.00 | 60.00 | EO |

| ID | Node | Cap [MW] | ηc | ηd | |

| SA1 | i8 | 200 | 0.95 | 0.9 | |

| SA2 | i17 | 120 | 0.95 | 0.9 | |

| ID | Node | SoCmin [%] | SoC0 [%] | Pcmax [%] | Pdmax [%] |

| SA1 | i8 | 20% | 20% | 30% | 30% |

| SA2 | i17 | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| Node | x (pu) | Limit (MVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| i1 | i2 | 0.0146 | 175 |

| i1 | i3 | 0.2253 | 175 |

| i1 | i5 | 0.0907 | 350 |

| i2 | i4 | 0.1356 | 175 |

| i2 | i6 | 0.205 | 175 |

| i3 | i9 | 0.1271 | 175 |

| i3 | i24 | 0.084 | 400 |

| i4 | i9 | 0.111 | 175 |

| i5 | i10 | 0.094 | 350 |

| i6 | i10 | 0.0642 | 175 |

| i7 | i8 | 0.0652 | 350 |

| i8 | i9 | 0.1762 | 175 |

| i8 | i10 | 0.1762 | 175 |

| i9 | i11 | 0.084 | 400 |

| i9 | i12 | 0.084 | 400 |

| i10 | i11 | 0.084 | 400 |

| i10 | i12 | 0.084 | 400 |

| i11 | i13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| i11 | i14 | 0.0426 | 500 |

| i12 | i13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| i12 | i23 | 0.0985 | 500 |

| i13 | i23 | 0.0884 | 500 |

| i14 | i16 | 0.0594 | 500 |

| i15 | i16 | 0.0172 | 500 |

| i15 | i21 | 0.0249 | 1000 |

| i15 | i24 | 0.0529 | 500 |

| i16 | i17 | 0.0263 | 500 |

| i16 | i19 | 0.0234 | 500 |

| i17 | i18 | 0.0143 | 500 |

| i17 | i22 | 0.1069 | 500 |

| i18 | i21 | 0.0132 | 1000 |

| i19 | i20 | 0.0203 | 1000 |

| i20 | i23 | 0.0112 | 1000 |

| i21 | i22 | 0.0692 | 500 |

| Initialization | Load system configuration (Sb, VPC, nodes, lines) Set time horizon (24 h) Define sets of conventional and renewable generators Define technical values of the network, storage systems and variable load. |

| Declare decision variables | |

| Establish objective function | |

| Restrictions | |

| Resolution | Construct the Aeq matrix of the nodal balance for each hour. Build a vector beq with hourly demand and renewable contributions. Construct matrices A and b for constraints:

SOLVE LP problem with linprog Options = optimoptions (‘linprog’,’ Display’,’ iter’, ‘Algorithm’, ‘dual-simplex’,’MaxIterations’,1e6); [x, fval, exitflag, output] = linprog(f, Aineq, bineq, Aeq, beq, lb, ub, options); Verify convergence: If exitflag > 0 then: Register fval, generation, SoC and DC flows. But: Report infeasibility and identify active restrictions |

| Results | They extract results: F_res = zeros (N, N, H); for e = 1:num_directed_edges i = Iidx(e); j = Jidx(e); for h = 1:H F_res(i,j,h) = x(getF(e,h)) * Sb; end end Reports and export

|

| Energy (MWh) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Sc 2 | Sc 1 |

| PG-Thermal | 35,601.48 | 35,641.97 |

| PG-Hydro | 11,520.00 | 11,520.00 |

| PG-FV | 1947.12 | 1947.12 |

| PG-EO | 3680.89 | 3572.44 |

| PCSA | −468.68 | |

| PdSA | 400.72 | |

| Demand | 52,681.53 | 52,681.53 |

| Costs (USD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Scenario 2 | Scenario 1 |

| Burden | 60,892.09 | |

| Discharge | −78,207.39 | |

| Wind | 203,981.11 | 197,891.68 |

| FV | 74,546.88 | 74,546.88 |

| Hydro | 147,098.63 | 147,170.11 |

| Thermal | 3,765,295.14 | 3,794,390.17 |

| Total | 4,173,606.45 | 4,213,998.84 |

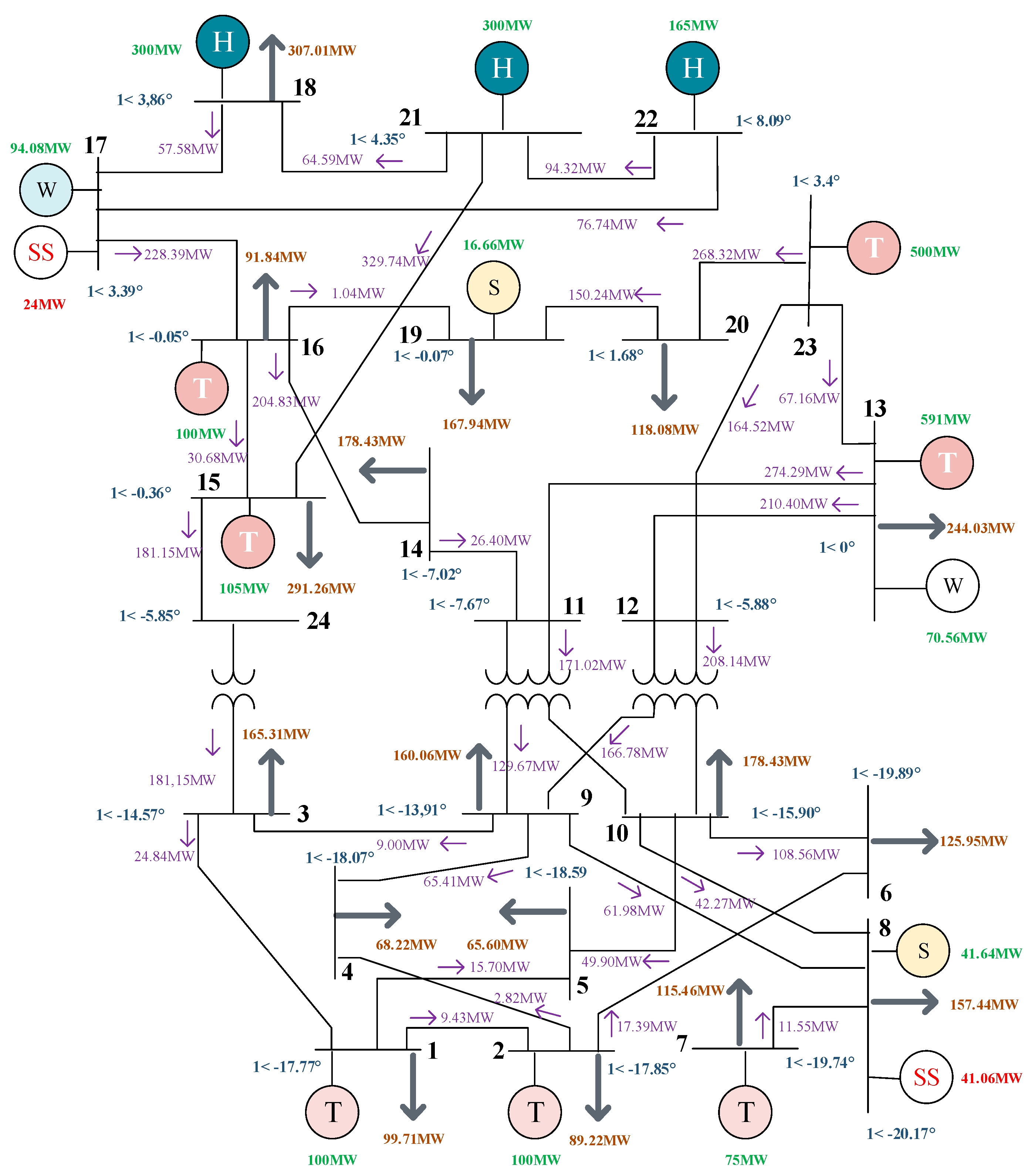

| Node | GT | GH | GFV | GEO | PDes | Dem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i1 | 100.00 | 99.71 | ||||

| i2 | 100.00 | 89.22 | ||||

| i3 | 165.31 | |||||

| i4 | 68.22 | |||||

| i5 | 65.60 | |||||

| i6 | 125.95 | |||||

| i7 | 75.00 | 115.46 | ||||

| i8 | 41.64 | 41.06 | 157.44 | |||

| i9 | 160.06 | |||||

| i10 | 178.43 | |||||

| i13 | 591.00 | 70.56 | 244.03 | |||

| i14 | 178.43 | |||||

| i15 | 105.00 | 291.26 | ||||

| i16 | 100.00 | 91.84 | ||||

| i17 | 94.08 | 24.00 | ||||

| i18 | 300.00 | 307.01 | ||||

| i19 | 16.66 | 167.94 | ||||

| i20 | 118.08 | |||||

| i21 | 300.00 | |||||

| i22 | 165.00 | |||||

| i23 | 500.00 | |||||

| Total | 1571.00 | 765.00 | 58.30 | 164.64 | 65.06 | 2624.00 |

| Node i | Node j | Flow (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| i1 | i2 | 9.43 |

| i1 | i5 | 15.70 |

| i2 | i4 | 2.82 |

| i2 | i6 | 17.39 |

| i3 | i1 | 24.84 |

| i7 | i8 | 11.55 |

| i9 | i3 | 9.00 |

| i9 | i4 | 65.41 |

| i9 | i8 | 61.98 |

| i10 | i5 | 49.90 |

| i10 | i6 | 108.56 |

| i10 | i8 | 42.27 |

| i11 | i10 | 171.02 |

| i11 | i9 | 129.67 |

| i12 | i10 | 208.14 |

| i12 | i9 | 166.78 |

| i13 | i11 | 274.29 |

| i13 | i12 | 210.40 |

| i14 | i11 | 26.40 |

| i15 | i24 | 181.15 |

| i16 | i14 | 204.83 |

| i16 | i15 | 30.68 |

| i16 | i19 | 1.04 |

| i17 | i16 | 228.39 |

| i18 | i17 | 57.58 |

| i20 | i19 | 150.24 |

| i21 | i15 | 329.74 |

| i21 | i18 | 64.59 |

| i22 | i17 | 76.74 |

| i22 | i21 | 94.32 |

| i23 | i12 | 164.52 |

| i23 | i13 | 67.16 |

| i23 | i20 | 268.32 |

| i24 | i3 | 181.15 |

| Technology | Power (MW) | Stake (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal generation (GT) | 1571 | 59.9% |

| Hydropower generation (GH) | 765 | 29.2% |

| Photovoltaic generation (PVG) | 58.3 | 2.2% |

| Wind power generation (GEO) | 164.6 | 6.3% |

| Download SAE (Pdes) | 65.1 | 2.5% |

| Generation + total download | 2624 | 100% |

| Indicator | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal utilization factor | 0.85 | The thermal units operate close to their nominal power, ensuring reliability |

| Renewable penetration (GH + GFV + GEO) | 37.7% | High non-conventional energy contribution, with grid stability |

| SAE participation | 2.5% | A key addition during peak hours |

| Maximum flow/line capacity | 0.85 pu | No overloads are present |

| Nodal balance compliance | 100% | Consistency of the optimization model |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Paredes, E.; Chilig, E.; Lata-García, J. Optimal Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks in Systems with Conventional Generation, Renewable, and Storage Systems Using DC Flows. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031372

Paredes E, Chilig E, Lata-García J. Optimal Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks in Systems with Conventional Generation, Renewable, and Storage Systems Using DC Flows. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031372

Chicago/Turabian StyleParedes, Erika, Edwin Chilig, and Juan Lata-García. 2026. "Optimal Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks in Systems with Conventional Generation, Renewable, and Storage Systems Using DC Flows" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031372

APA StyleParedes, E., Chilig, E., & Lata-García, J. (2026). Optimal Electrical Dispatch by Time Blocks in Systems with Conventional Generation, Renewable, and Storage Systems Using DC Flows. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031372