Acoustic Absorption Behavior of Boards Made from Multilayer Packaging Waste

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Materials Processing Methodology

2.3. Morphological Analysis

2.4. Acoustic Properties

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Characterization

3.2. Sound Absorption Coefficients

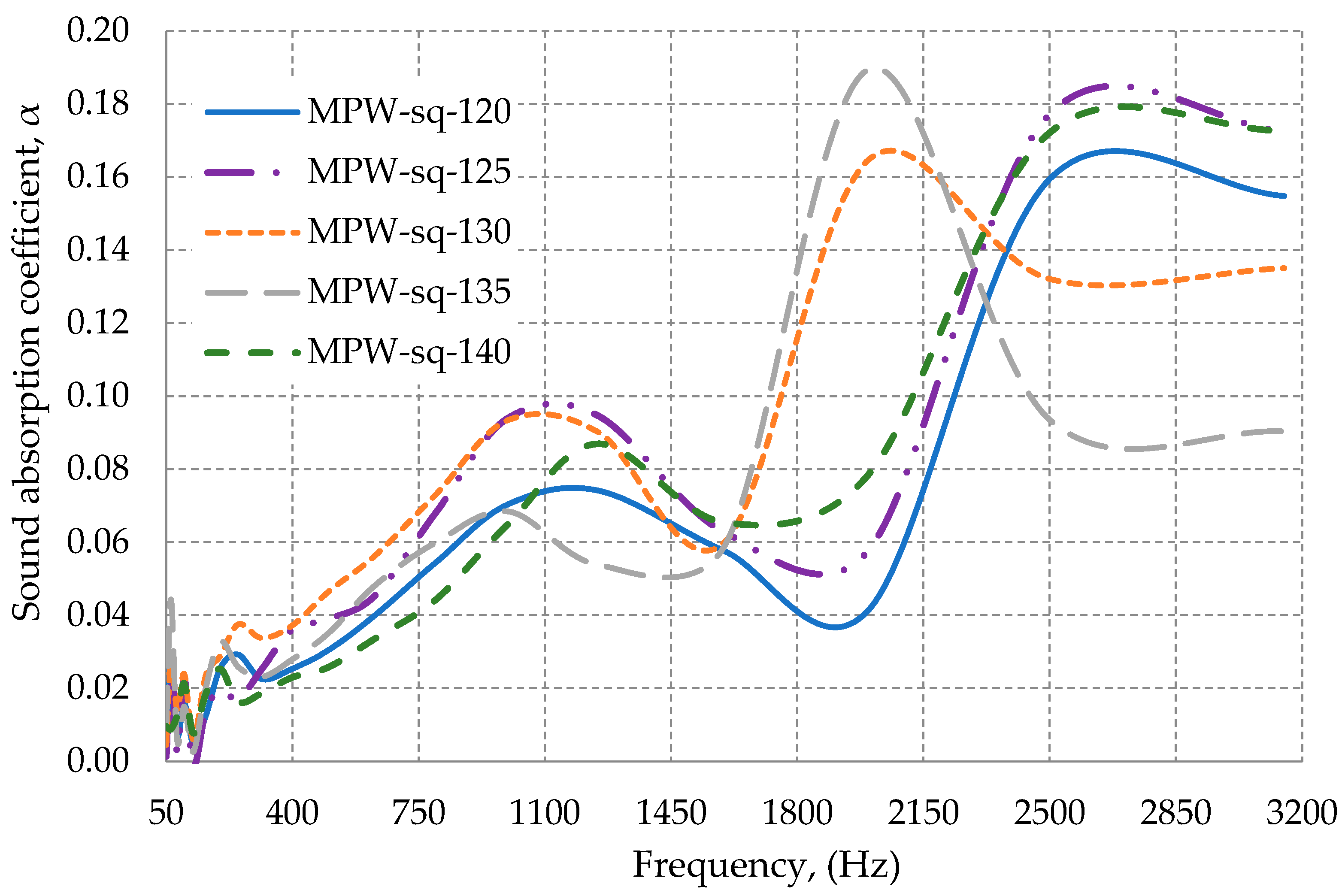

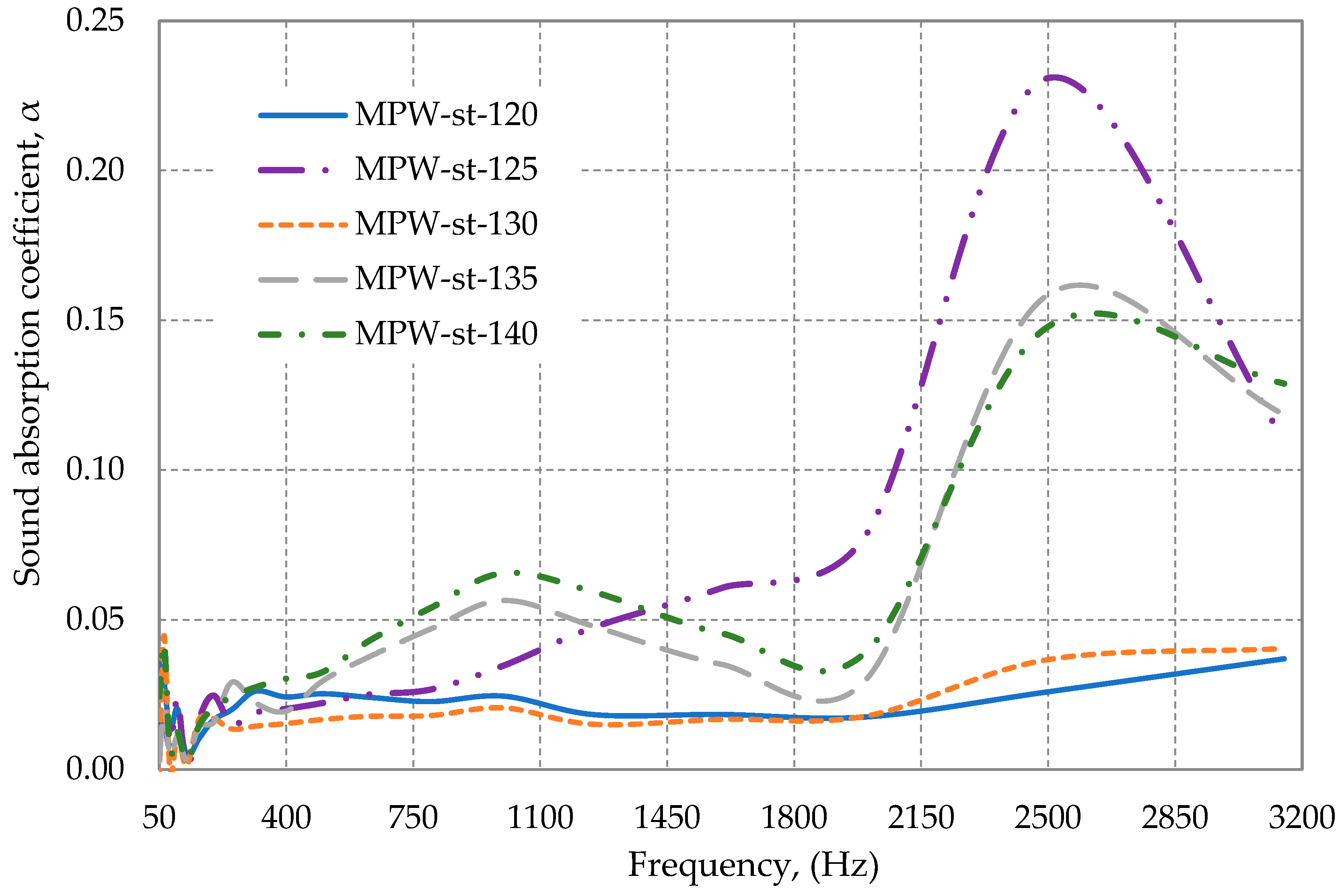

3.2.1. Influence of the Shape of Multilayer Packaging Waste on Sound Absorption Coefficient

3.2.2. Influence of the Temperature on Sound Absorption Coefficient

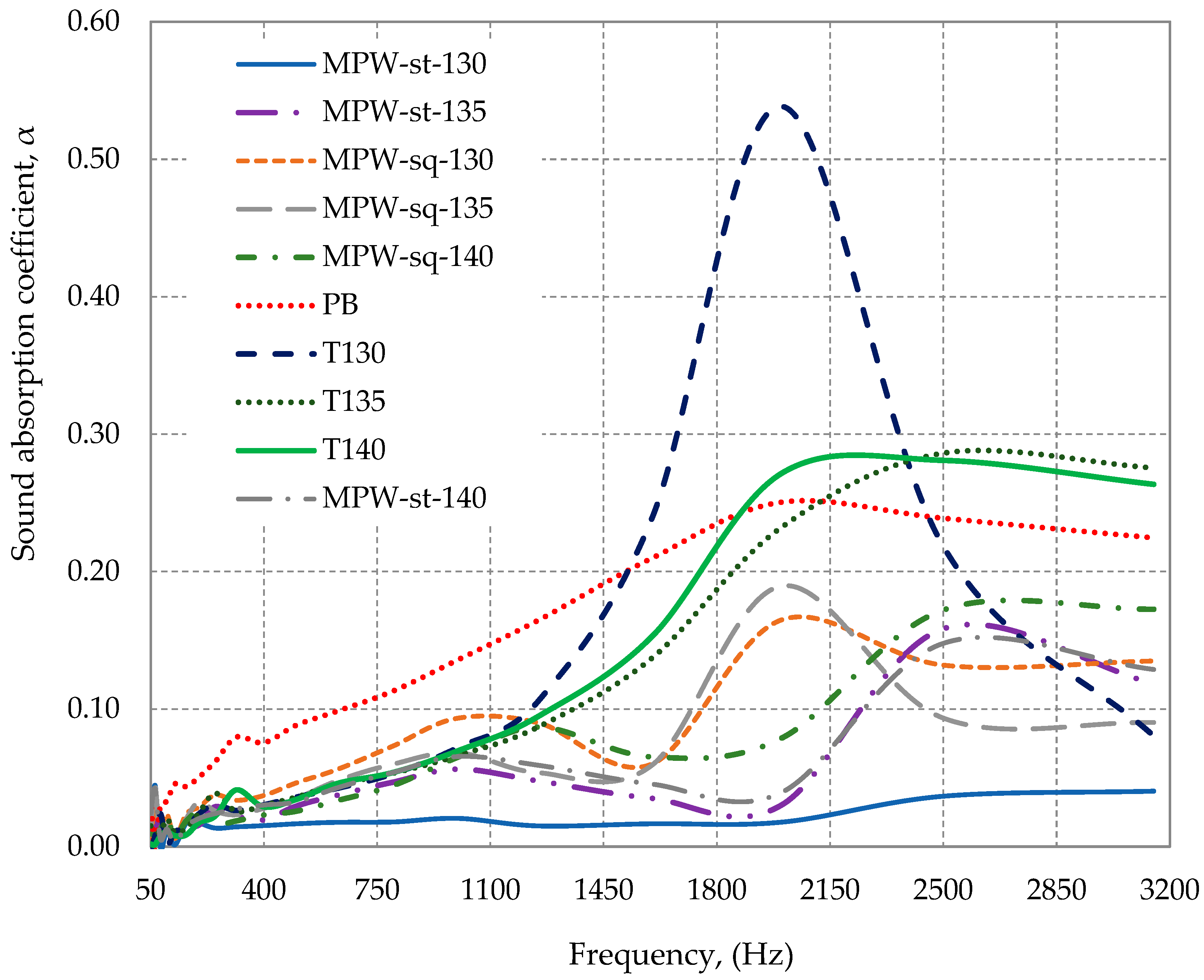

3.2.3. Comparison of the Absorption Coefficient with Other Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Recupido, F.; Lama, G.C.; Lavorgna, M.; Buonocore, G.G.; Marzella, R.; Verdolotti, L. Post-consumer recycling of Tetra Pak®: Starting a ‘new life’ as filler in sustainable polyurethane foams. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhofer, S.; Schneider, F.; Obersteiner, G. The ecological relevance of transport in waste disposal systems in Western Europe. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, S47–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadiak, J. Tetra Pak Recycling—Current Trends and New Developments. Am. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E. Environmental Impact of Compostable Polymer Materials. In Compostable Polymer Materials; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, C.I.K.; Lavoie, J.-M.; Huneault, M.A. Separation and reuse of multilayer food packaging in cellulose reinforced polyethylene composites. Waste Biomass Val. 2016, 8, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Barrera, G.; De la Colina-Martínez, A.L.; Martínez-Lopez, M.; del Coz-Díaz, J.J.; Gencel, O.; Avila-Cordoba, L.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Varela-Guerrero, V.; Martínez-Lopez, A. Recovery and reuse of waste tetra pak packages by using a novel treatment. In Trends in Beverage Packaging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 303–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seier, M.; Archodoulaki, V.M.; Koch, T.; Duscher, B.; Gahleitner, M. Polyethylene terephthalate based multilayer food packaging: Deterioration effects during mechanical recycling. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, K.E.; Zhou, C.; Rojas, O.J.; Nkeuwa, W.N.; Dai, C. Moulded pulpibers for disposable food packaging: A state-of-the-art review. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydary, J.; Susa, D.; Dudáš, J. Pyrolysis of aseptic packages (tetrapak) in a laboratory screw type reactor and secondary thermal/catalytic tar decomposition. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, G.L. Recycling of aseptic beverage cartons: A review. Recycling 2021, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúniga-Muro, N.M.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Mendoza-Castillo, D.I.; Duran-Valle, C.J.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Reynel-Ávila, H.E.; Tapia-Picazo, J.C. Recycling of Tetra Pak wastes via pyrolysis: Characterization of solid products and application of the resulting char in the adsorption of mercury from water. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulou, I.; Pappa, G.D.; Vouyiouka, S.N.; Magoulas, K. Recycling of post-consumer multilayer Tetra Pak® packaging with the Selective Dissolution-Precipitation process. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 165, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Batista, M.J.; Blázquez, G.; Franco, J.F.; Calero, M.; Martín-Lara, M.A. Recovery, separation and production of fuel, plastic and aluminum from the Tetra Pak waste to hydrothermal and pyrolysis processes. Waste Manag. 2022, 137, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, L.L.; Luo, K.; Sun, Z.X.; Mei, X.X. Separation properties of aluminium-plastic laminates in post-consumer Tetra Pak with mixed organic solvent. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, G.G.; Karaboyacı, M. Process and machinery design for the recycling of Tetra Pak components. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Barrera, G.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Cuevas-Yañez, E.; Varela-Guerrero, V.; Vigueras-Santiago, E.; Ávila-Córdoba, L.; Martínez-López, M. Waste cellulose from Tetra Pak packages as reinforcement of cement concrete. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2015, 682926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platnieks, O.; Barkane, A.; Ijudina, N.; Gaidukova, G.; Thakur, V.K.; Gaidukovs, S. Sustainable Tetra Pak recycled cellulose/ Poly(Butylene succinate) based woody-like composites for a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, M.; Martínez-Barrera, G.; Barrera-Díaz, C. Waste Tetra Pak particles from beverage containers as reinforcements in polymer mortar: Effect of gamma irradiation as an interfacial coupling factor. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, M.; Russo, V.; Oliviero, M.; Verdolotti, L.; Sorrentino, A.; di Serio, M.; Tesser, R.; Iannace, S.; Lavorgna, M. Synthesis and characterization of sustainable polyurethane foams based on polyhydroxyls with different terminal groups. Polymer 2018, 149, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Gryshchuk, L.; Moimare, P.; Bossa, F.d.L.; Santillo, C.; Barak-Kulbak, E.; Verdolotti, L.; Boggioni, L.; Lama, G.C. Chemically functionalized cellulose nanocrystals as reactive filler in bio-based polyurethane foams. Polymers 2021, 13, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białkowska, A.; Krzykowska, B.; Zarzyka, I.; Bakar, M. Polymer/layered clay/polyurethane nanocomposites: P3HB hybrid nanobiocomposites—Preparation and properties evaluation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomboș, A.M.; Nemeș, O.; Soporan, V.F.; Vescan, A. Toward new composite materials starting from Multi-layer waste. Studia UBB Chemia 2008, 53, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rancea, M.; Nemeș, O.; Bizo, L. Thermal behaviour of composite materials obtained from recycled TETRA PAK® by thermoplasting forming. Studia UBB Chemia 2025, 70, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamir, L.; Nongkynrih, B.; Gupta, S.K. Community noise pollution in urban India: Need for public health action. Indian J. Community Med. 2014, 39, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, S.; Kucuk, H. Investigation of industrial tea-leaf-fibre waste material for its sound absorption properties. Appl. Acoust. 2009, 70, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN ISO 604:2002; Plastics—Determination of Compressive Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- EN ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN 1602:2013; Plastics—Determination of Apparent Density—Part 1: General Principles. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- ISO EN 10534-2:2002; Acoustics—Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient and Impedance in Impedances Tubes Part 2: Transfer-Function Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Gwon, J.G.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, J.H. Sound absorption behavior of flexible polyurethane foams with distinct cellular structures. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, R.; Vasanthakumari, R.; Padmanabhan, C. Sound Absorption, thermal and mechanical behavior of polyurethane foam modified with nano silica, nano clay and crumb rubber fillers. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 4, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, G.H.; Ha, C.S. Sound absorption properties of polyurethane/nanosilica nanocomposite foams. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 2384–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.H.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, K.S.; Oh, S.M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Jeong, H.M. Sound Damping of a PU Foam Nanocomposite. In Proceedings of the 2008 Third International Forum on Strategic Technologies, Novosibirsk, Russia, 23–29 June 2008; IEEE: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2008; pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.-M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Drzal, L.T.; Lee, E.; Mielewski, D.F.; Misra, M. Effect of sequential mixing and compounding conditions on cellulose acetate/layered silicate nanocomposites. J. Polym. Environ. 2006, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doutres, O.; Atalla, N.; Dong, K. A Semi-phenomenological model to predict the acoustic behavior of fully and partially reticulated polyurethane foams. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 054901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doutres, O.; Atalla, N.; Dong, K. Effect of the microstructure closed pore content on the acoustic behavior of polyurethane foams. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 064901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, G.; Castro, A.; Vechiatti, N.; Iasi, F.; Armas, A.; Marcovich, N.E.; Mosiewicki, M.A. Biobased porous acoustical absorbers made from polyurethane and waste tire particles. Polym. Test. 2017, 57, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Fu, Q.; Si, Y.; Ding, B.; Yu, J. Porous materials for sound absorption. Compos. Commun. 2018, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Khair, A.; Yang, J.; Han, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of sound absorption performance in porous concrete pavement with crushed stone base course. Sci. Rep. 2026, 16, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso, M.; de Brito, J.; Silvestre, J.D. Characterization of eco-efficient acoustic insulation materials (traditional and innovative). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiqah, A.; Jawaid, M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ishak, M.R. Dynamic mechanical properties of sugar palm/glass fiber reinforced thermoplastic polyurethane hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koruk, H.; Koc, B.; Genc, G. Acoustic and mechanical properties of biofibers and their composites. In Advances in Bio-Based Fiber; Rangappa, S.M., Puttegowda, M., Parameswaranpillai, J., Siengchin, S., Gorbatyuk, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 407–446. [Google Scholar]

- Platon, M.A.; Nemeș, O.; Tiuc, A.E.; Vasile, O.; Padurețu, S. Phono-Absorbent behavior of new fiberglass plates from mixed plastic material wastes. In Advanced Structured Materials, Materials Design and Applications III; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 149, pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Temperature (°C) | Multilayer Packaging Waste Shape |

|---|---|---|

| MPW-sq-120 | 120 | square |

| MPW-sq-125 | 125 | |

| MPW-sq-130 | 130 | |

| MPW-sq-135 | 135 | |

| MPW-sq-140 | 140 | |

| MPW-st-120 | 120 | strips |

| MPW-st-125 | 125 | |

| MPW-st-130 | 130 | |

| MPW-st-135 | 135 | |

| MPW-st-140 | 140 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rancea, M.; Nemeș, O.; Tiuc, A.-E.; Vasile, O. Acoustic Absorption Behavior of Boards Made from Multilayer Packaging Waste. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031206

Rancea M, Nemeș O, Tiuc A-E, Vasile O. Acoustic Absorption Behavior of Boards Made from Multilayer Packaging Waste. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031206

Chicago/Turabian StyleRancea, Miron, Ovidiu Nemeș, Ancuța-Elena Tiuc, and Ovidiu Vasile. 2026. "Acoustic Absorption Behavior of Boards Made from Multilayer Packaging Waste" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031206

APA StyleRancea, M., Nemeș, O., Tiuc, A.-E., & Vasile, O. (2026). Acoustic Absorption Behavior of Boards Made from Multilayer Packaging Waste. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031206