1. Introduction

Almost three million die every year in workplace accidents, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Moreover, an estimated 395 million accidents and cases of occupational disease take place globally on a yearly basis. While most of these accidents are non-lethal, a significant portion causes the victims to be temporarily disabled [

1].

Among these industries, the highest risks to workers are in construction, forestry, fishing, manufacturing, and mining sectors, which together account for around 63% of reported fatal accidents [

2]. Of the sectors, metalworking is the most affected by workplace injuries [

3].

Serious accidents, in particular, are often caused by electrical mishaps. The first few minutes following the fall are crucial, as it is essential to turn off the electricity (without touching the victim) and call emergency services. These accidents take place primarily while working on stationary low-voltage installations (cabinets, boxes, sockets), operating electrical tools, and in the surroundings of aerial lines, transformer substations, and underground pipes.

The magnitude of these problems has motivated a large body of work on understanding, predicting, and preventing accidents in the workplace, including that supported by machine learning technology. Such methods allow for the detection of risk factors as well as the prediction of the severity of events with historical data.

A few studies have investigated the use of machine learning for the analysis and prediction of workplace accidents. For instance, ref. [

4] tested the Random Forests (RF) and the Stochastic Gradient Tree Boosting (SGTB) algorithms to predict injury category, body part affected, and accident severity from construction site reports.

Meanwhile, ref. [

5] compared a set of algorithms (Support Vector Machines (SVM), Logistic Regression (LR), RF, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Decision Trees (DT), and Naive Bayes (NB)) for accident report classification. The SVM model exhibited the best outcome, with an F1 score ranging from 0.45 to 0.92.

In terms of cognitive factors, ref. [

6] integrated Reasoned Action Theory (RAT) into machine learning models for the prediction of the percentage of risky actions of construction workers. They employed a decision tree-based model with an accuracy of 97.6%.

Likewise, ref. [

7] employed distinct models (DT, RF, LR, k-NN, and SVM) to forecast accident severity, where the Random Forest model was found to be the most potent.

More recently, ref. [

8] applied machine learning techniques to classify injury types in construction accidents using large-scale Australian datasets comparable to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) statistics, demonstrating the effectiveness of supervised learning for handling heterogeneous accident data.

In Korea, ref. [

9] developed a predictive model to determine the likelihood of fatal accidents, with a prediction rate of 91%. Reference [

10] used the Random Forest algorithm to categorize accident types in a system that deals with class imbalance by subsampling, achieving 71.3 percent accuracy.

Some other studies, such as [

11], addressed the role of safety training and fall height in the severity level of accidents. Reference [

12] developed a hybrid approach, logistic regression combined with neuro-fuzzy systems—ANFIS, to predict the risk of scaffolding falls.

More recently, several research works have followed these analyses. Reference [

13] applied ML algorithms to predict the severity of collapse-related incidents in the construction industry and showed that ML models are sufficient to rank the critical causes. In another study [

14], it was shown that a customized combination of multiple machine learning algorithms can be used to predict occupational accidents, indicating the influence of feature selection on prediction performance. In the industrial field, several studies, for example [

15], have highlighted the potential of classification models such as random forest or gradient boosting to anticipate dangerous events. In a different application context, a study conducted in South African national parks applied several machine learning algorithms—including Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), XGBoost, and Neural Networks—to predict occupational injury types and analyze unsafe conditions using data from national parks in South Africa [

16]. In addition, ref. [

17] applied learning and ensemble learning approaches to automatically identify the causes of fall-related accidents from investigation reports, enabling automatic extraction of human and environmental factors. Other research, such as that by [

18], has proposed interpretable models for analyzing major risk indicators in the offshore oil industry, combining machine learning and explainability of results. In another study that examined the energy industry, a number of machine learning models were employed to classify industrial accidents, and their findings indicated that these procedures can facilitate the extraction of useful patterns to know more about the different groups of incidents [

19]. Finally, recent studies [

20,

21] have compared different machine learning methods applied to national accident databases, particularly in the metallurgical sector, and have incorporated feature optimization techniques to improve the detection and prevention of occupational injuries. Similarly, ref. [

22] predicted occupational accidents at the level of Brazilian states using multiple machine learning models, including regression-based approaches and LightGBM, highlighting regional disparities in accident occurrence.

In the transportation domain, ref. [

23] applied machine learning models to predict traffic accident severity in Montreal, showing that data-driven approaches can effectively identify high-risk scenarios and support preventive decision-making. Similarly, ref. [

24] proposed a classification-based framework to identify high-risk road segments and accident severity patterns using categorical data, highlighting the effectiveness of machine learning in handling heterogeneous accident-related variables.

In addition to road traffic safety, machine learning techniques have also been widely used for the analysis of construction and industrial accidents. Reference [

25] built a factor and scenario-based prediction framework of construction accidents based on a machine learning method and highlighted the significance of human, technical, and environmental factors for predicting accidents. Their results are consistent with previous studies that emphasized the importance of classification and ensemble learning techniques in occupational safety.

In a more recent study, ref. [

26] used interpretable machine learning techniques along with data augmentation to discover infrastructure-related causes that contribute to accidents on the road. Their work points to the increasing relevance of model interpretability in potentially life-saving applications, where it is important to know how individual risk factors contribute to supporting urgent decision-making.

While these works demonstrated the power of machine learning to predict accident severities and conduct risk analysis, there are few studies that consider both severities of accident outcomes at the same time and analyze cross-domain accidents. Those two outcomes of occupational health and safety predictive modeling have received little attention in the past, especially for predicting both the human and environmental factors in accidents, such as those that may occur in the energy sector. This research gap motivates the present study, which aims to compare multiple machine learning models to predict accident-related human and environmental factors and to support data-driven risk management strategies.

Overall, existing research demonstrates the potential of machine learning for proactive prevention of workplace accidents. However, several methodological limitations remain. A number of studies use small datasets and focus only on a subset of accidents or do not explicitly examine the issue regarding class imbalance, which can have a drastic impact on performance measures (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score). Furthermore, the selection and reporting of evaluation metrics differ greatly between studies, which further complicates comparison and lowers reproducibility. Moreover, the majority of related works focus on either building or overall industrial industries or only work with structural data, not many utilize natural language descriptions or have special attention to the energy domain.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes building a predictive model using structured variables and textual accident reports in the energy sector to identify fatal and non-fatal factors that lead to an accident. We use a common set of evaluation metrics that are justified to a reasonable level, which can help achieve reliable performance assessment and provide some assurance against class imbalance. The goal of this study is to provide more stable, interpretable, and generalizable predictions that can be followed up on in the safety management process as an early preventive measure based on a data-driven approach using a relatively large dataset and several classification algorithms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Structuring and Source Description

The dataset is based on accident cases, and it includes 4739 reported industrial accidents, where each contains the following eight key variables: accident date, narrative summary, degree of injury, nature of injury, affected body part, accident type, human factors, and environmental factors.

Table 1 shows an example of an accident scenario that is extracted from the dataset.

The data were downloaded from Kaggle in the dataset titled “OSHA HSE DATA_ALL ABSTRACTS 15–17_FINAL”, and represent a set of industrial accident records gathered from public summaries issued by occupational safety organizations. Despite the structured attributes, the dataset contains textual descriptions of accident scenarios, which allows for the joint analysis of information from both unstructured and structured sources.

Human and environmental factors were categorized in the original dataset using predetermined categories derived from occupational safety classifications established for various industrial domains. The authors did not conduct additional manual annotation. Before modeling, an extensive data pre-processing stage was performed to ensure the quality and consistency of the raw data. This involved addressing missing structured values by imputation (or discarding where appropriate), standardizing consistent non-line item labeling, aggregating low-occurrence categorical values, and eliminating redundant records. Also, the free-form narrative text descriptions were cleaned, and the categorical variables were encoded to make them compatible with suitable machine learning models before training.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

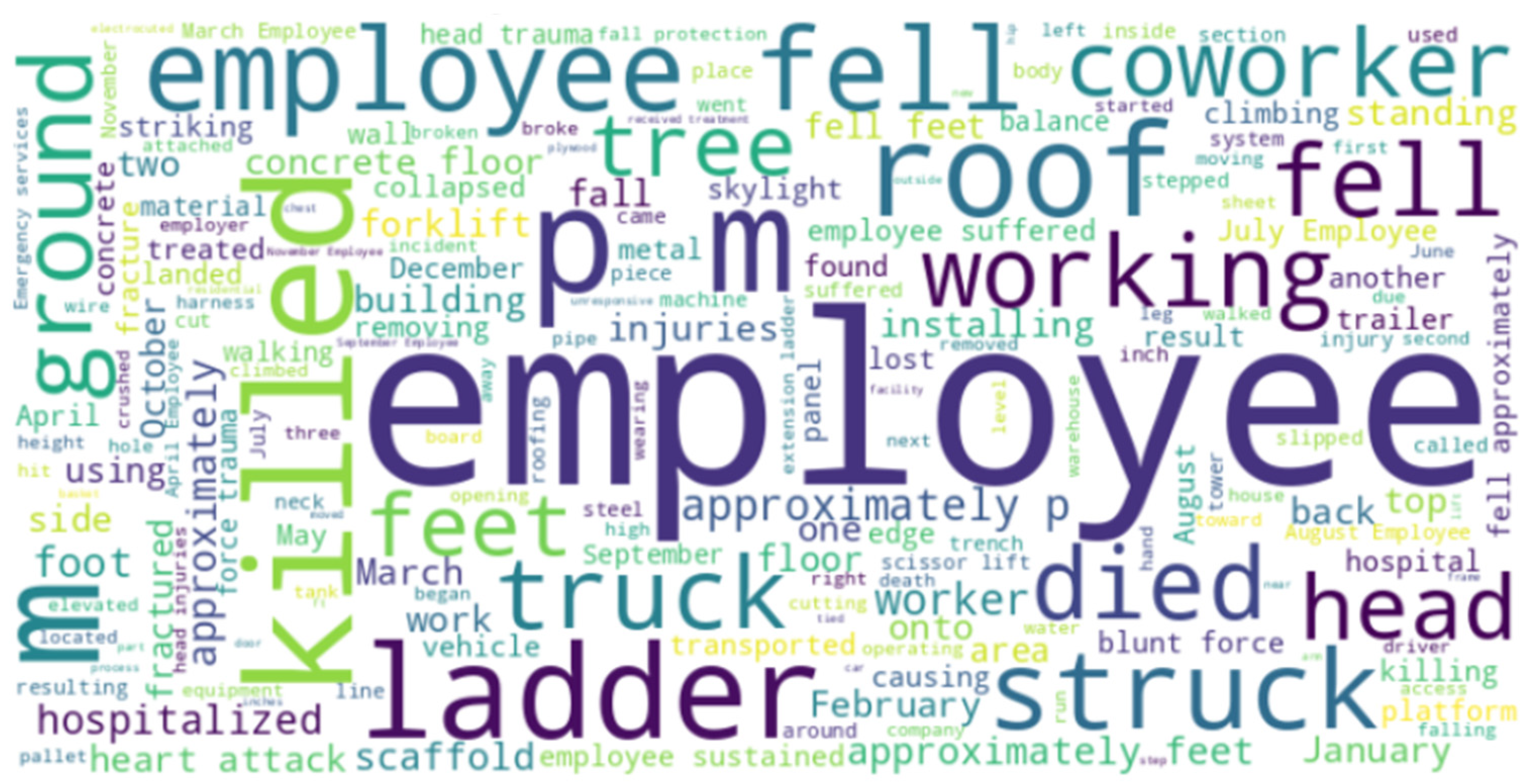

To obtain deeper semantic and analytical insights from the dataset, a comprehensive data preprocessing phase was carried out prior to the analysis. This step aims to enhance data quality, reduce noise, and ensure the reliability of subsequent modeling tasks. In addition to the general preprocessing of structured variables, particular attention was given to the textual data contained in the dataset.

For the textual attributes, a dedicated text preprocessing pipeline was applied. First, text normalization was performed to ensure consistency across documents. This included converting all characters to lowercase, removing punctuation marks, numbers, and special characters, and correcting encoding inconsistencies.

Next, tokenization was applied, whereby each text entry was segmented into individual tokens (words). This step enables the transformation of raw text into analyzable units suitable for natural language processing tasks.

Subsequently, stop word removal was conducted to eliminate common and non-informative words (such as articles, prepositions, and conjunctions) that do not contribute significantly to the semantic meaning of the text. This helps reduce dimensionality and improve the efficiency of the analysis.

To further refine the textual representation, stemming and lemmatization techniques were employed. Stemming reduces words to their root forms by removing suffixes, while lemmatization maps words to their canonical dictionary forms, taking into account their grammatical context. These processes help group semantically similar terms and mitigate vocabulary sparsity.

After completing the text preprocessing steps, the cleaned and standardized textual features were integrated with the structured variables. The main variables are then described qualitatively in

Table 2, emphasizing what they measure, their structure, and their contribution to accident characterization.

2.3. Factors Taken into Account in the Database

Table 3 shows the two factors included in the dataset that were extracted from the database used, grouped into two main categories: human factors and environmental factors. This classification supports accident cause analysis and the development of targeted prevention strategies.

2.4. Encoding of Categorical Variables and Textual Data

Categorical features were digitized in a manner consistent with the characteristics of the variables themselves prior to model training. The binary outcome variable, “Degree of Injury”, was defined as 1 for fatal accidents and 0 for non-fatal ones. Other categorical variables, such as “Part of Body”, “Accident Type”, “Nature of Injury”, as well as human and environmental factors, were converted into labels and assigned unique integer codes to ensure computational compatibility while preserving data brevity for nominal fields.

For the textual component, the accident descriptions “Accident Summary” were first subjected to a text preprocessing phase. After preprocessing, the cleaned textual data were vectorized using the Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) method. The n-gram range was set to (1, 2) to capture both individual terms and common word sequences.

Table 4 summarizes the encoding and vectorization techniques applied.

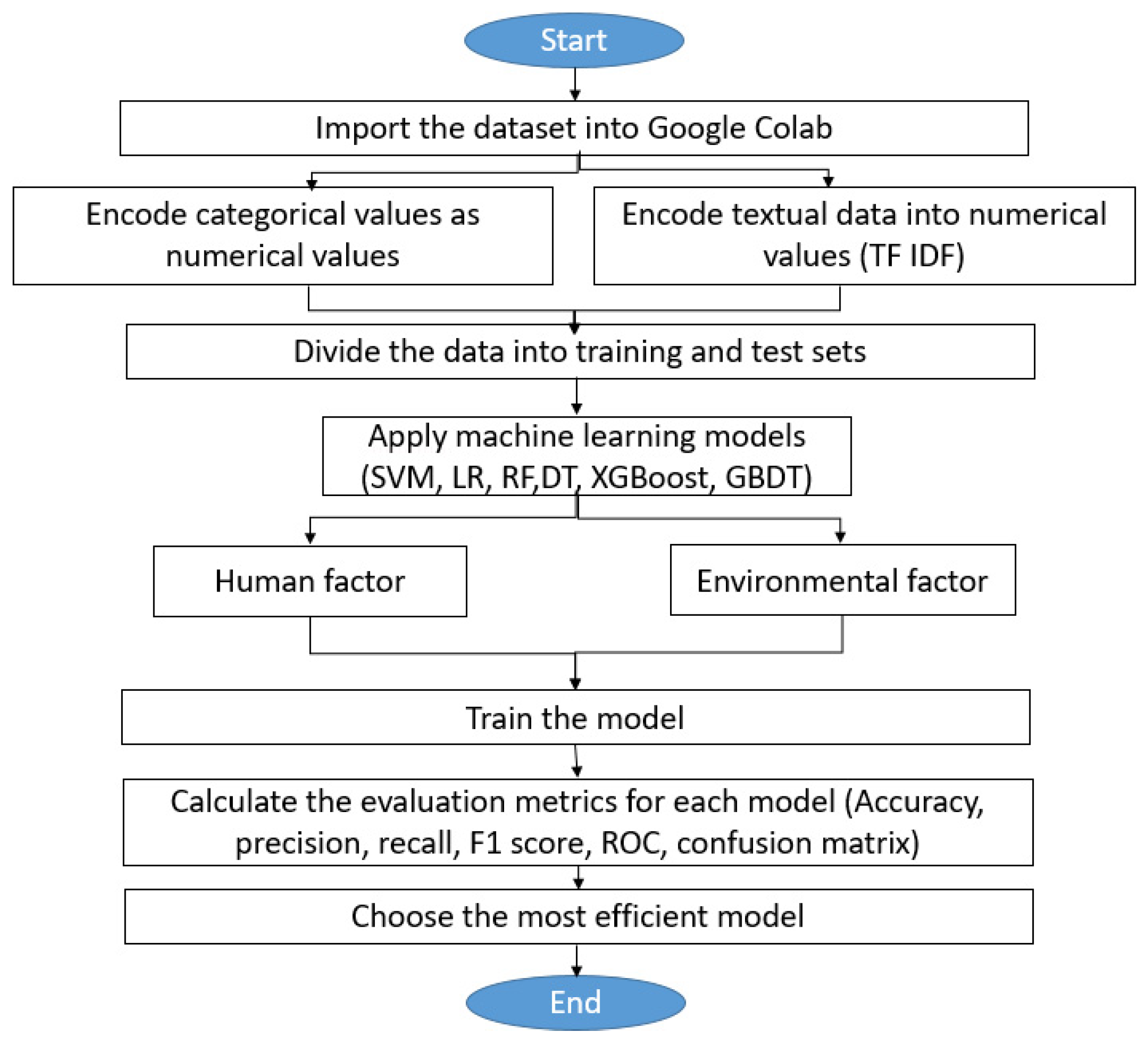

2.5. Model Configuration and Evaluation Strategy

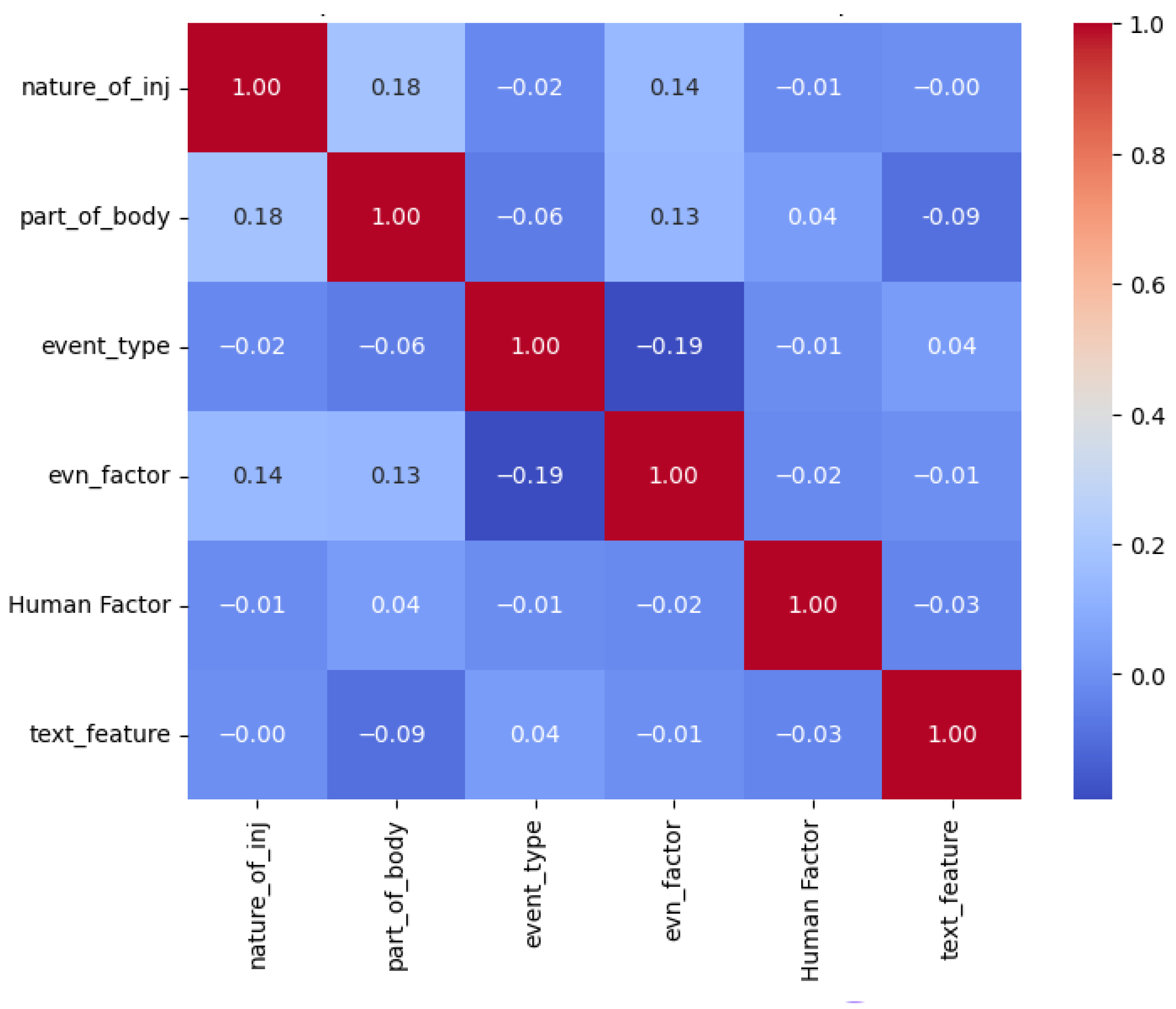

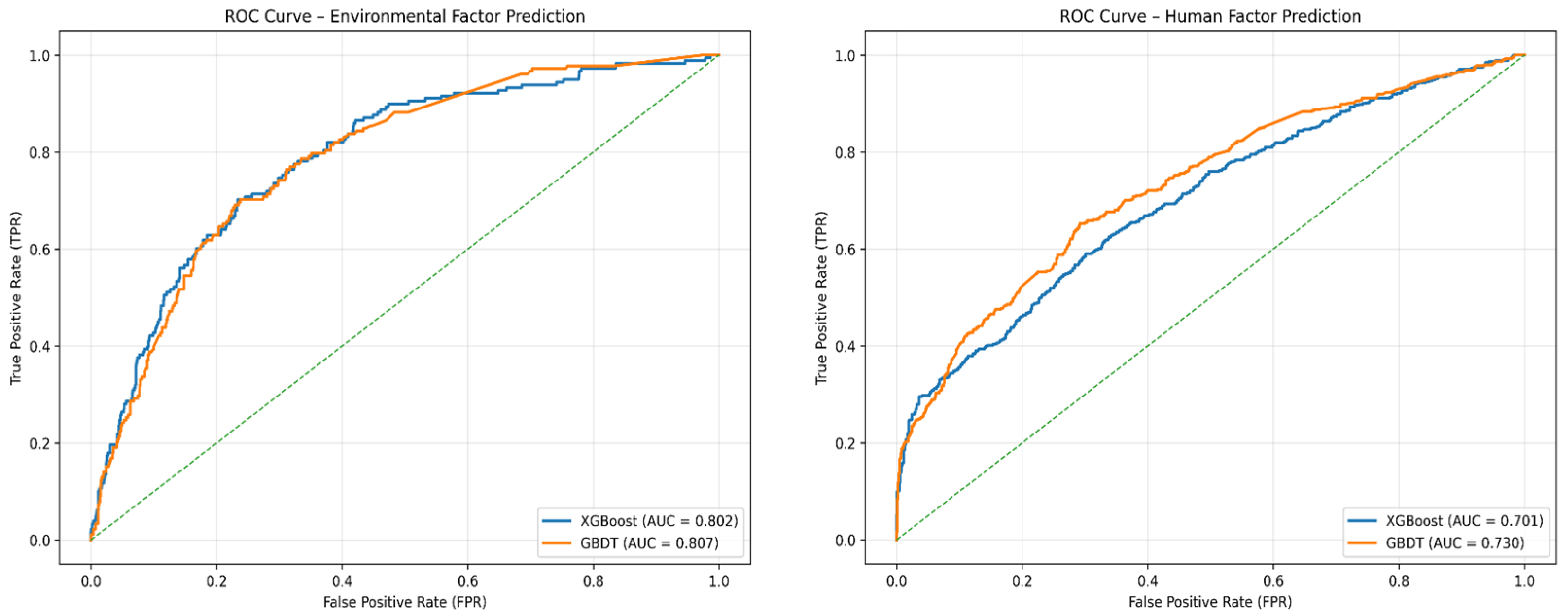

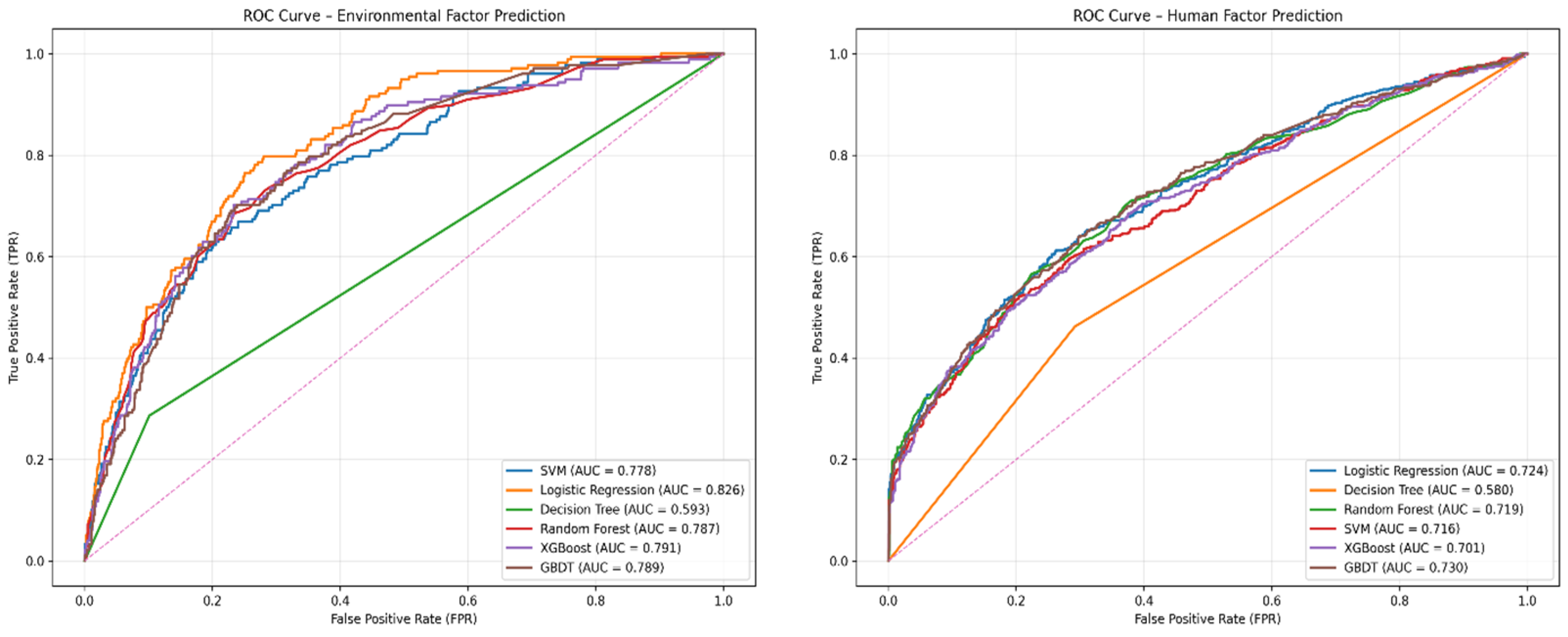

Six machine learning models were applied to the dataset, including Random Forest, decision trees, logistic regression, support vector classification, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT). Before training, categorical values were encoded as numerical values, and textual data was transformed into numerical values using the TF-IDF method. In total, 70% of the data was used for model training and 30% for testing. After training and testing the models, evaluation metrics—accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score—were calculated for each factor to estimate classification performance. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was then plotted. The best model according to the results obtained was chosen, and several other results were taken into account, such as the correlation heat map, feature importance, ROC curve, confusion matrix, and graphical representation of each factor. All steps, including data import and model testing, were performed on Google Colab.

Figure 1 shows the methodological logic we followed in this study. All ML-models were trained using the default parameters from scikit-learn.

4. Discussion

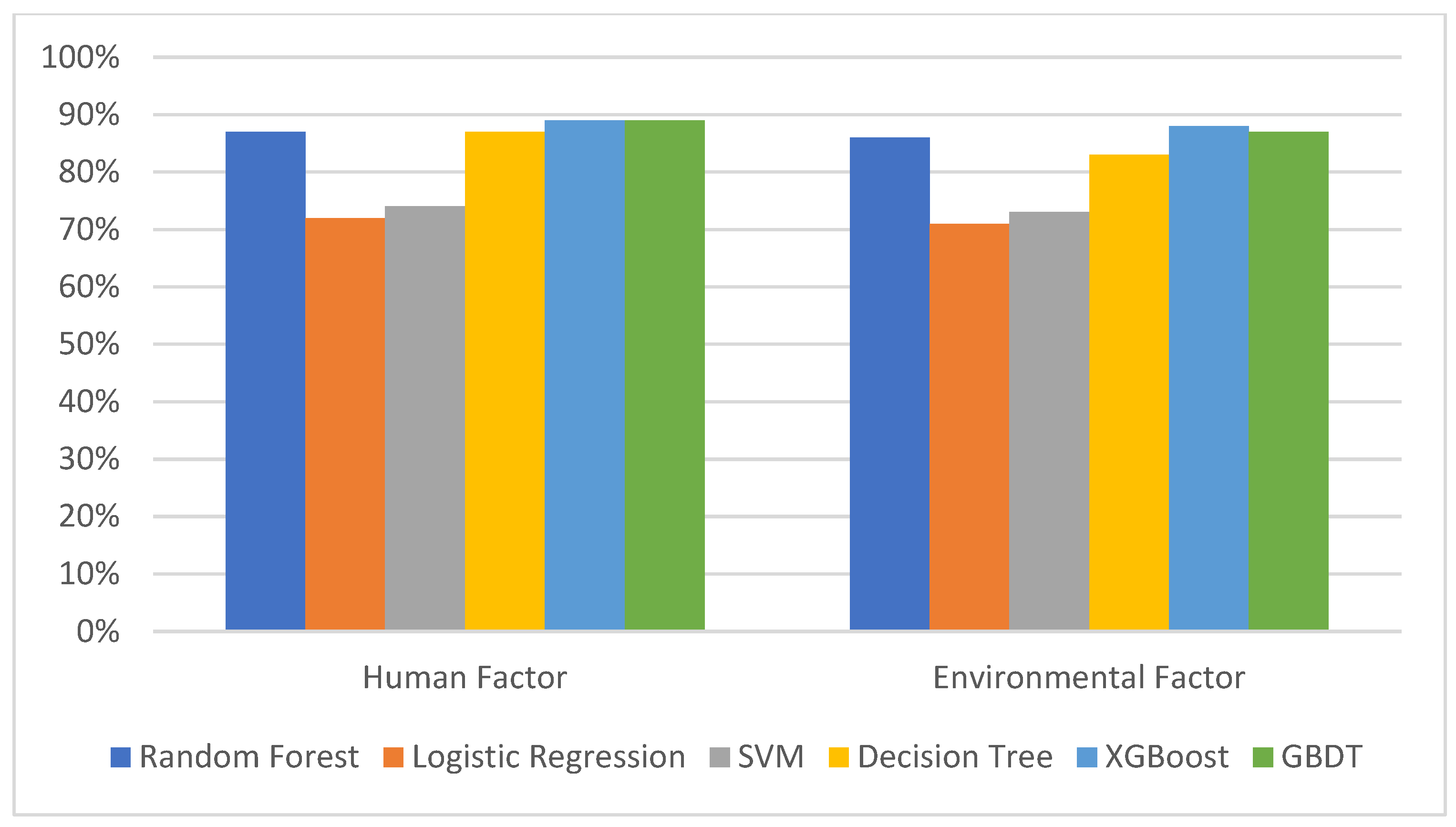

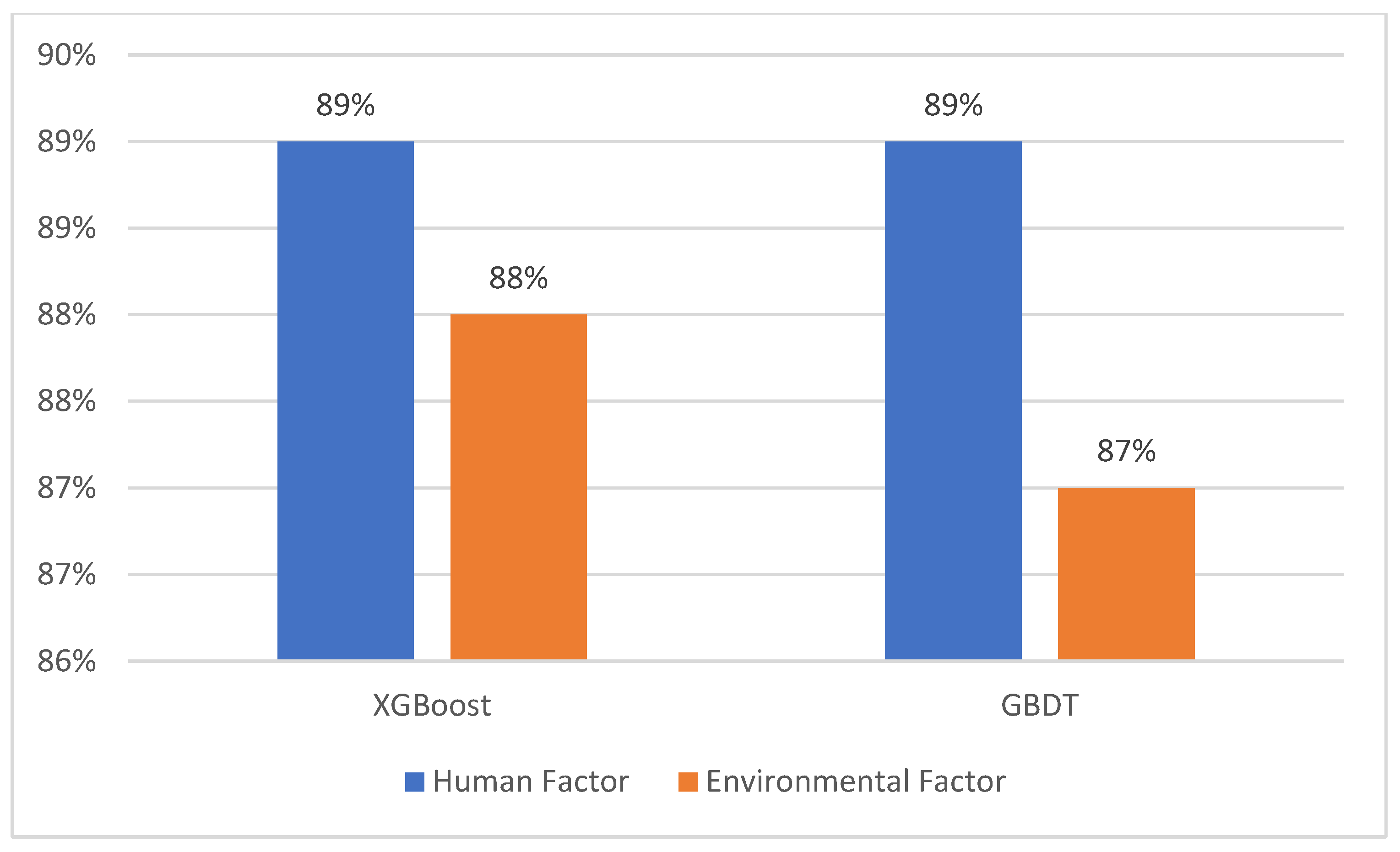

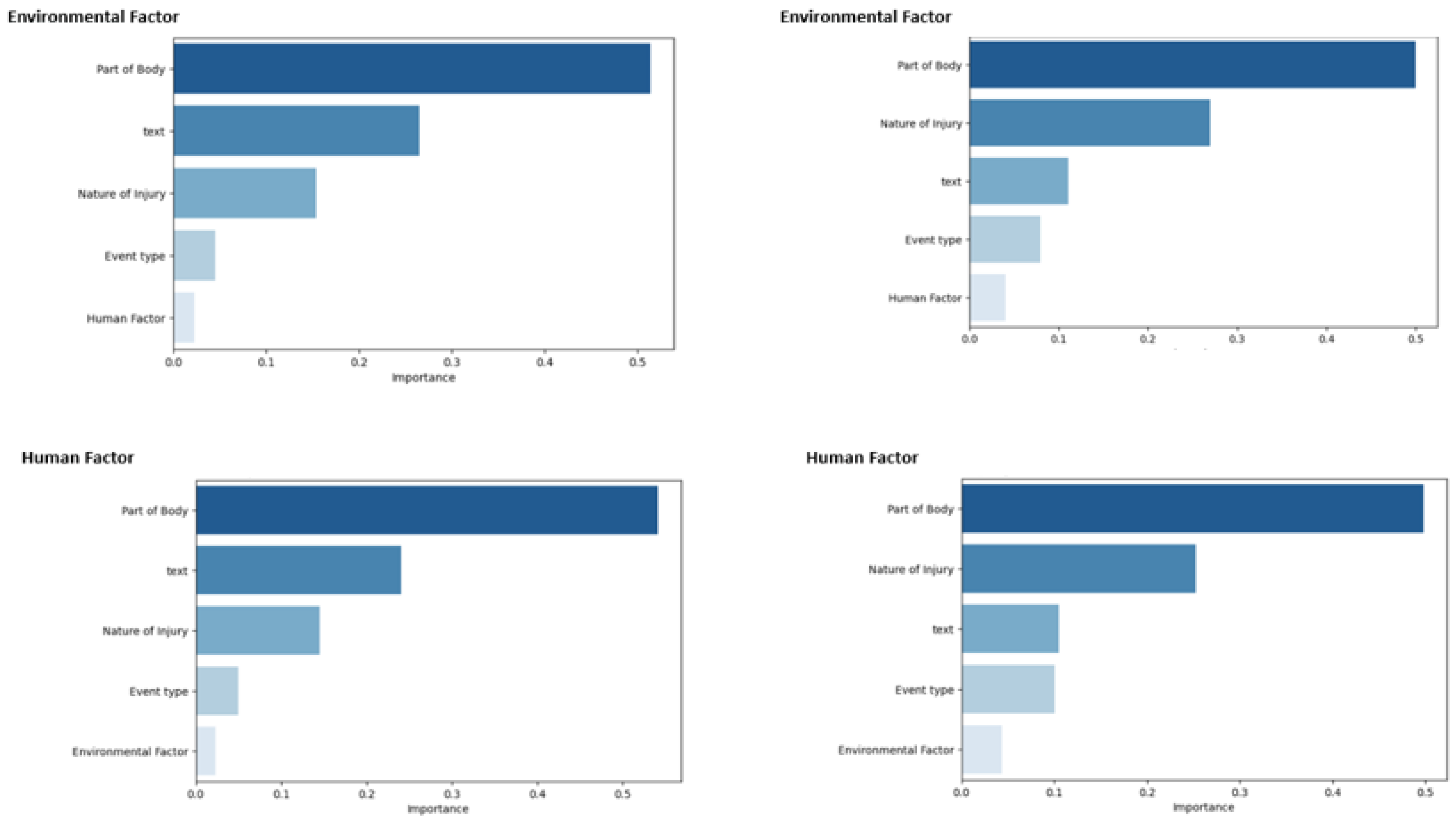

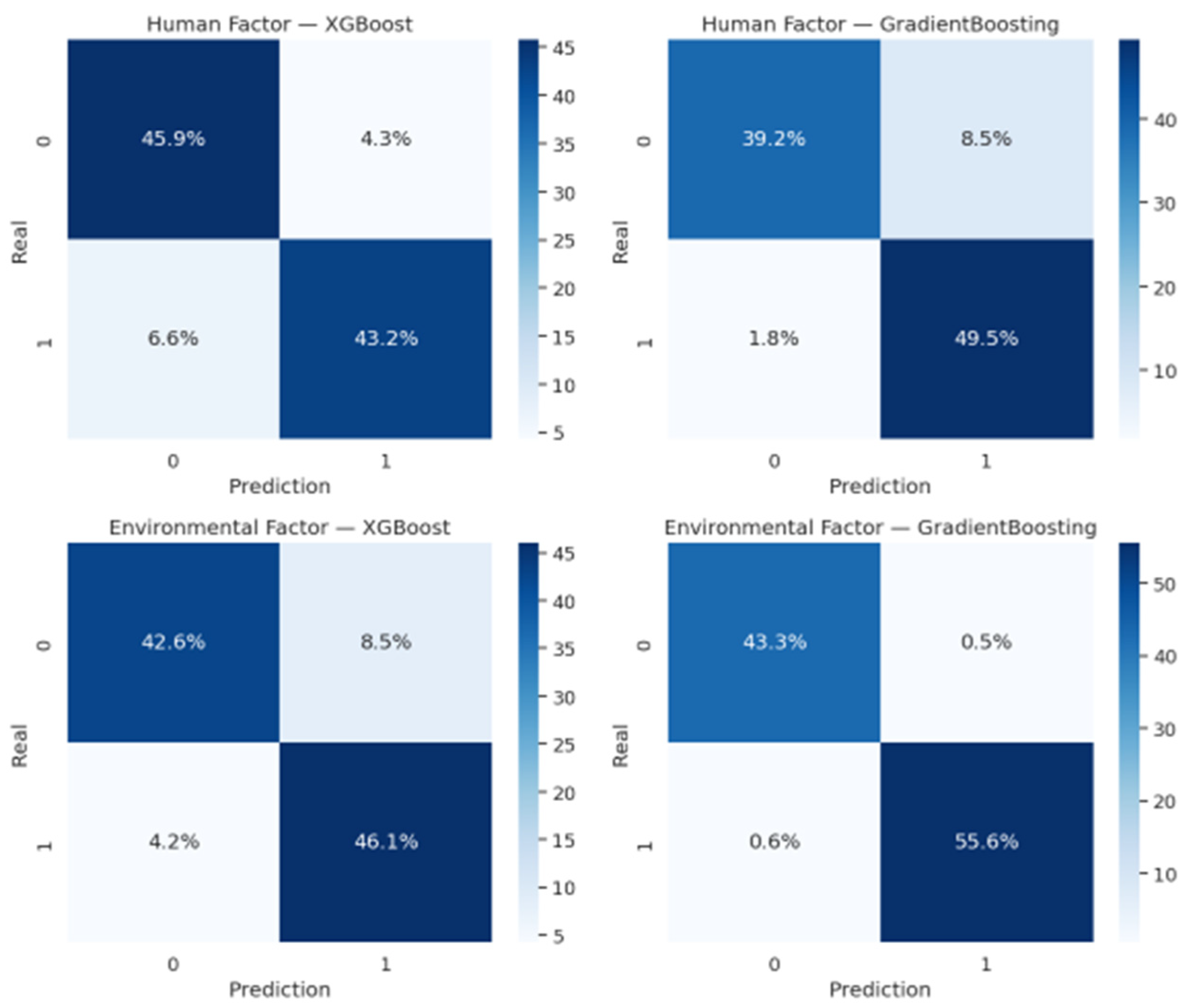

The findings of this research validate the efficiency of machine learning to predict industrial accidents in terms of human and environmental factors. Of the tested models, gradient boosting-based algorithms (particularly XGBoost and GBDT) showed superior accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score compared with conventional models like logistic regression, decision tree, and SVM. This superior performance could be attributed to their capability of modeling intricate nonlinear relationships of explanatory variables with accident occurrence, while controlling interactions among diverse risk factors.

Comparing these results to the literature, a high level of agreement is observed. References [

13,

14] have also indicated the good performance of gradient boosting models to classify and predict occupational accidents. Also, ref. [

17] confirmed that ensemble learning methods improve the robustness of automatic accident cause identification. These findings indicate that boosting-based models are an effective way to enhance the performance of industrial risk management systems.

Early foundational studies laid the groundwork for applying machine learning to occupational safety analysis. For example, ref. [

11] demonstrated the influence of safety training and fall height on injury severity using statistical and machine learning approaches. Similarly, ref. [

4] were among the first to apply ensemble learning methods to predict injury severity and affected body parts from construction accident reports. These studies established the feasibility of data-driven approaches for occupational accident analysis, which later research expanded using larger datasets and more advanced algorithms.

Analysis of the most important factors showed that variables associated with human error, together with some forms of environmental degradation (e.g., temperature or visibility conditions and workspace clutter), are highly determinant of accidents. This finding supports what has been confirmed in previous research [

18,

21] that addresses the integration between mechanical and human factors to obtain a comprehensive picture of industrial risk.

In addition, recent studies highlight the diversity of applications and regional contexts. In North America, ref. [

21] used public OSHA data to predict injury severity using multiple machine learning models. In South America, ref. [

22] applied similar techniques at the state level in Brazil, demonstrating regional disparities in accident occurrence. Reference [

8] focused on construction in Australia, using large-scale datasets aligned with OECD standards to classify injury types, while [

16] analyzed unsafe conditions in South African national parks using SVM, k-NN, and XGBoost, illustrating adaptability in a non-industrial context. These regional differences emphasize the importance of adaptable machine learning frameworks that can generalize across various industrial and environmental contexts.

We should, however, point out some limitations of the proposed models despite their good performance. The success of predictions is highly contingent on the representativeness and balance of the available data. Even though the use of TF-IDF vectorization has allowed us to appropriately handle the text-based variables, using unbalanced and/or incomplete data can lead to a bias in learning. On the other hand, boosting models are quite efficient yet still partially “black-box,” thereby limiting their interpretability, which is a major concern for their application in industrial settings like the energy sector.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, our approach introduces methodological improvements that address several of these challenges. Compared to previous studies, the present work extends the literature in several ways. Most prior research focuses on single outcomes or specific sectors, whereas this study jointly analyzes human and environmental factors and considers both fatal and non-fatal outcomes. Unlike studies relying solely on structured data, the proposed framework integrates structured variables with textual accident descriptions, enhancing the richness of extracted risk patterns. Furthermore, the use of consistent evaluation metrics and explicit handling of class imbalance addresses methodological limitations often reported in prior studies.

Building on the above discussion, there are a few recommendations. If explainability is desired, then one can also incorporate explainability, such as SHAP or LIME, to understand the importance of each factor in the prediction. Also, combining a variety of data (incident reports, industrial sensors, feedback) may help make the model more robust. Lastly, incorporating these predictive models into industrial risk management systems can serve as a proactive system capable of identifying early warnings and safety information useful for making safety-related decisions.

The proposed machine learning models demonstrate promising performance in predicting human and environmental risk factors associated with industrial accidents. In the energy sector, these models can support proactive risk identification across various domains, such as electricity generation and transmission, oil and gas operations, and nuclear energy facilities.

In the electricity sector, the models are particularly applicable to accident scenarios involving maintenance activities, electrical hazards, and environmental conditions such as weather-related risks. The availability of structured incident reports and operational logs facilitates the integration of machine learning-based risk prediction tools into safety management systems.

In the oil and gas industry, where accidents often involve complex interactions between human factors, hazardous materials, and harsh environmental conditions, the models can assist in identifying recurring risk patterns related to human error, fatigue, and unsafe operational practices. However, the diversity of operational contexts (onshore vs. offshore) and the presence of rare but high-consequence events may limit generalization without sector-specific data.

For the nuclear energy sector, although the number of accidents is relatively limited, the critical nature of potential consequences highlights the importance of robust risk assessment. The applicability of data-driven models in this domain may be constrained by data scarcity, strict confidentiality requirements, and highly regulated operational environments. As a result, machine learning models should be considered as decision-support tools rather than standalone risk assessment mechanisms.

Overall, while the proposed approach shows strong potential for enhancing safety management in the energy industry, its effectiveness depends on data quality, representativeness, and sector-specific adaptation. Future research may focus on incorporating domain-specific features, expert knowledge, and advanced modeling techniques to improve generalization across different energy subsectors.

5. Conclusions

This research illustrated that the use of machine learning processes to predict industrial accidents, considering human and environmental factors, is important. Based on a structured database and TF-IDF vectorization for processing text variables, some algorithm models were used to compare the performances, such as Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, Random Forest, XGBoost, and GBDT. The results indicate that the best overall performance is provided by the models based on gradient boosting (XGBoost and GBDT), which confirms their capacity to capture complex relationships among the explanatory variables and accident occurrence.

The findings reported here have resulted in an improved comprehension of the mechanism of development of accidents, emphasizing the role played by human and environment in their genesis. The aforementioned model also allows the risk analysis process to be more objectifiable and less dependent on expert judgement, enabling decisions to be made on the basis of numerical information.

From a practical standpoint, models can be implemented in risk management systems to reinforce prevention and forecast hazardous situations, making them available for industrial safety policy. Yet, the limitations we have uncovered—and, in particular, concerns over data quality and balance, as well as model interpretability—point to opportunities for further work to make predictions more transparent and actionable.

Future research directions will thus include incorporating explainability methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME), employing more sophisticated resampling techniques to address class imbalance with various loss functions and metrics, and leveraging the next generation of language models (BERT, RoBERTa) for improved understanding of accident-related language. In the long-term, we hope that this approach can contribute to the digitization and automation of industrial models management using AI techniques in order to improve safety, reliability, and resilience in complex systems.

In this study, the default hyperparameters provided by the scikit-learn library were used for all evaluated machine learning models to ensure a fair and consistent comparison across algorithms. The main objective of this work is not to optimize or fine-tune model hyperparameters, but rather to evaluate and compare classical machine learning techniques for identifying human and environmental factors influencing industrial accidents. By adopting uniform baseline configurations, the analysis highlights the relative performance of each algorithm under comparable conditions and establishes a reference framework for future research. Hyperparameter optimization is considered a potential extension of this work and will be addressed in future studies to further enhance model performance.

Although the present study focuses on model development and performance evaluation, the practical integration of the proposed machine learning framework into existing Safety Management Systems (SMS) represents an important direction for future work. In operational settings, the predicted human and environmental risk indicators could be incorporated as decision-support inputs within SMS dashboards to enable continuous risk monitoring. Such predictions may support proactive safety interventions, including targeted training programs addressing identified human-factor vulnerabilities, adaptive operational procedures under elevated environmental risk conditions, and prioritized inspections or audits for high-risk scenarios. Future research should further investigate system interoperability, real-time data integration, and the definition of actionable risk thresholds to ensure that model outputs can be translated into effective, timely, and context-aware safety management interventions.