Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study on Influencing Factors of Barium Sulfate Scaling in Low-Permeability Sandstone Reservoirs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Key Scaling Ions and Flow Conditions on Scaling Behavior

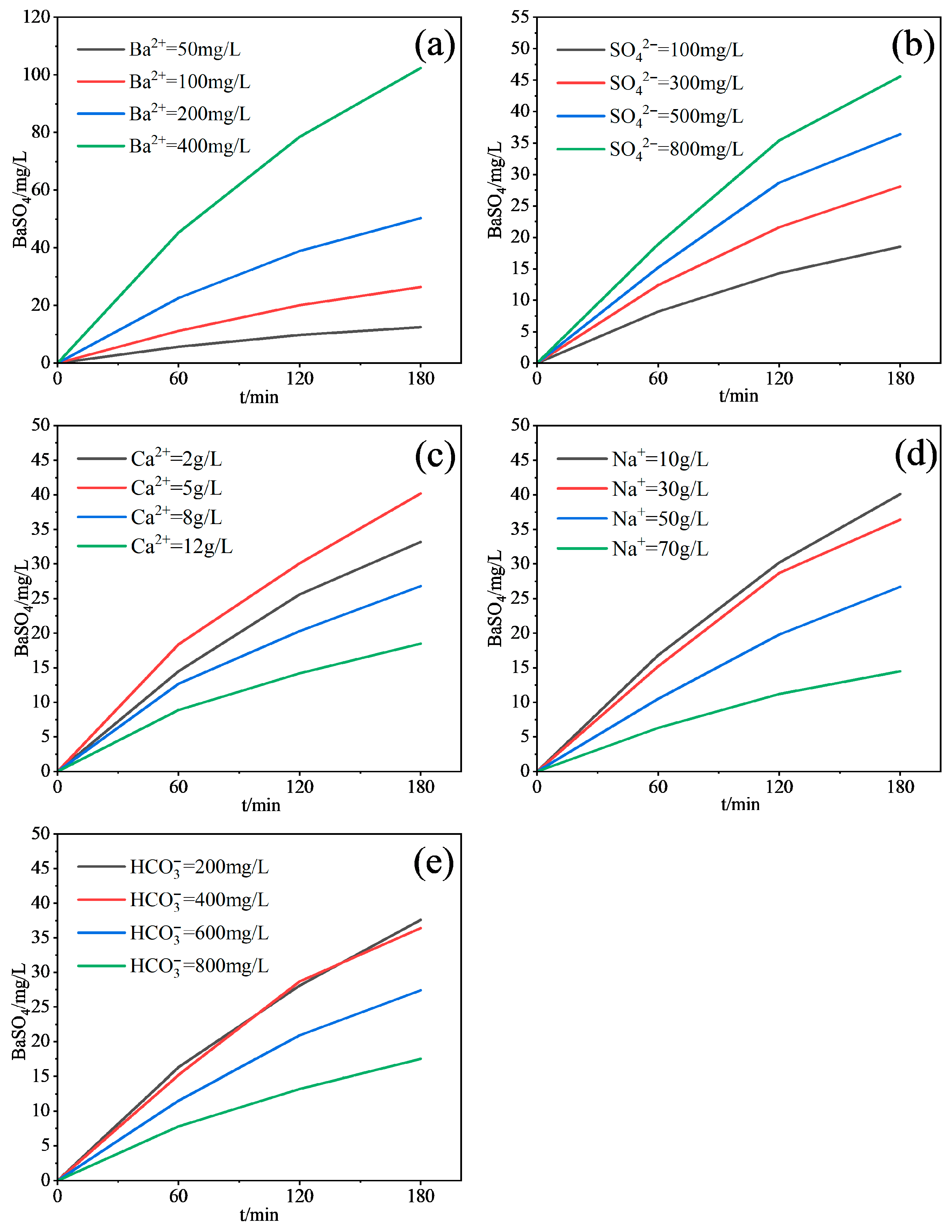

3.1.1. Influence of Key Scaling Ions

3.1.2. Influence of Injection Conditions

Influence of Injection Velocity

Influence of Injection Pressure

3.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Barium Sulfate Deposition

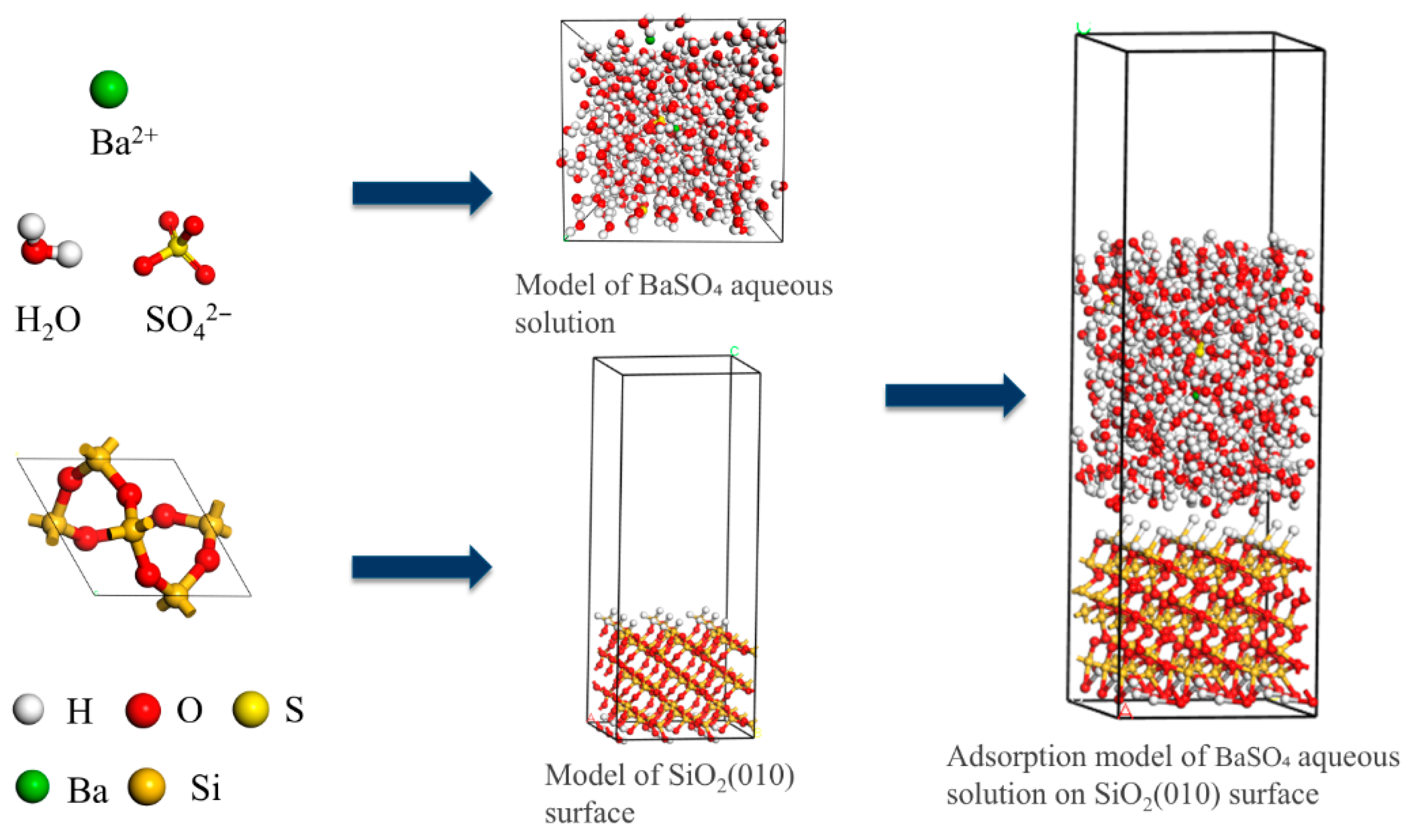

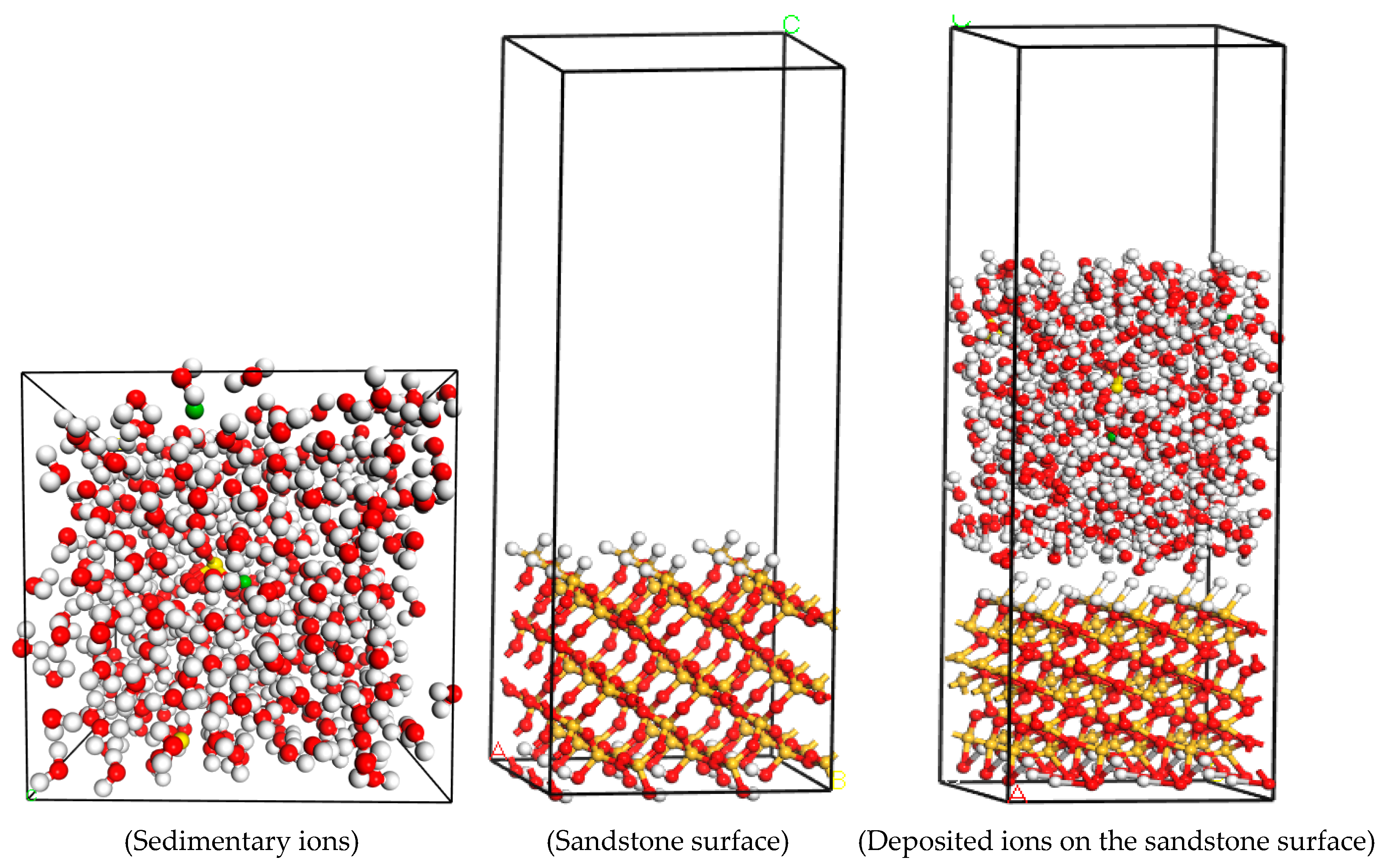

3.2.1. Model Establishment

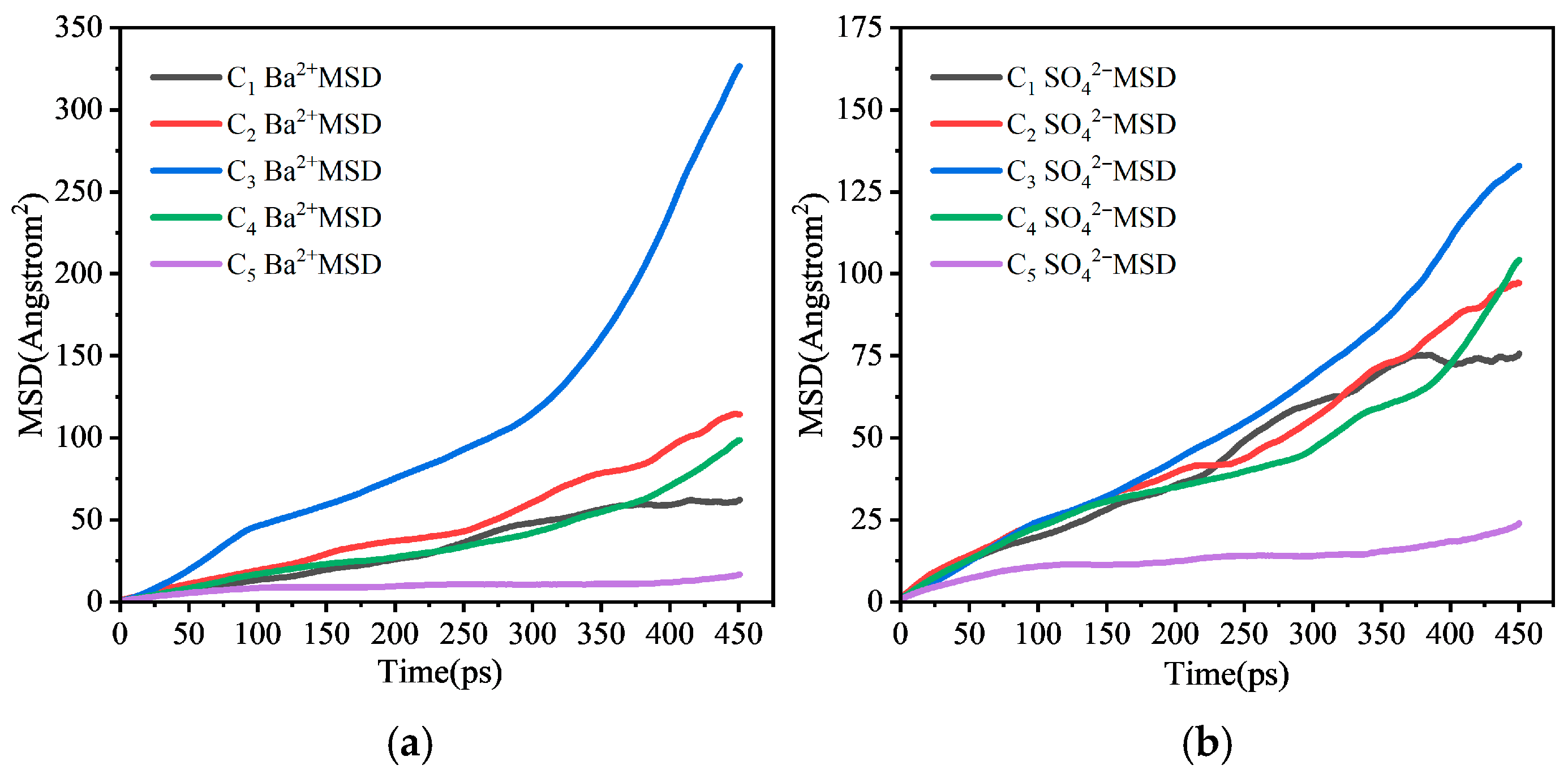

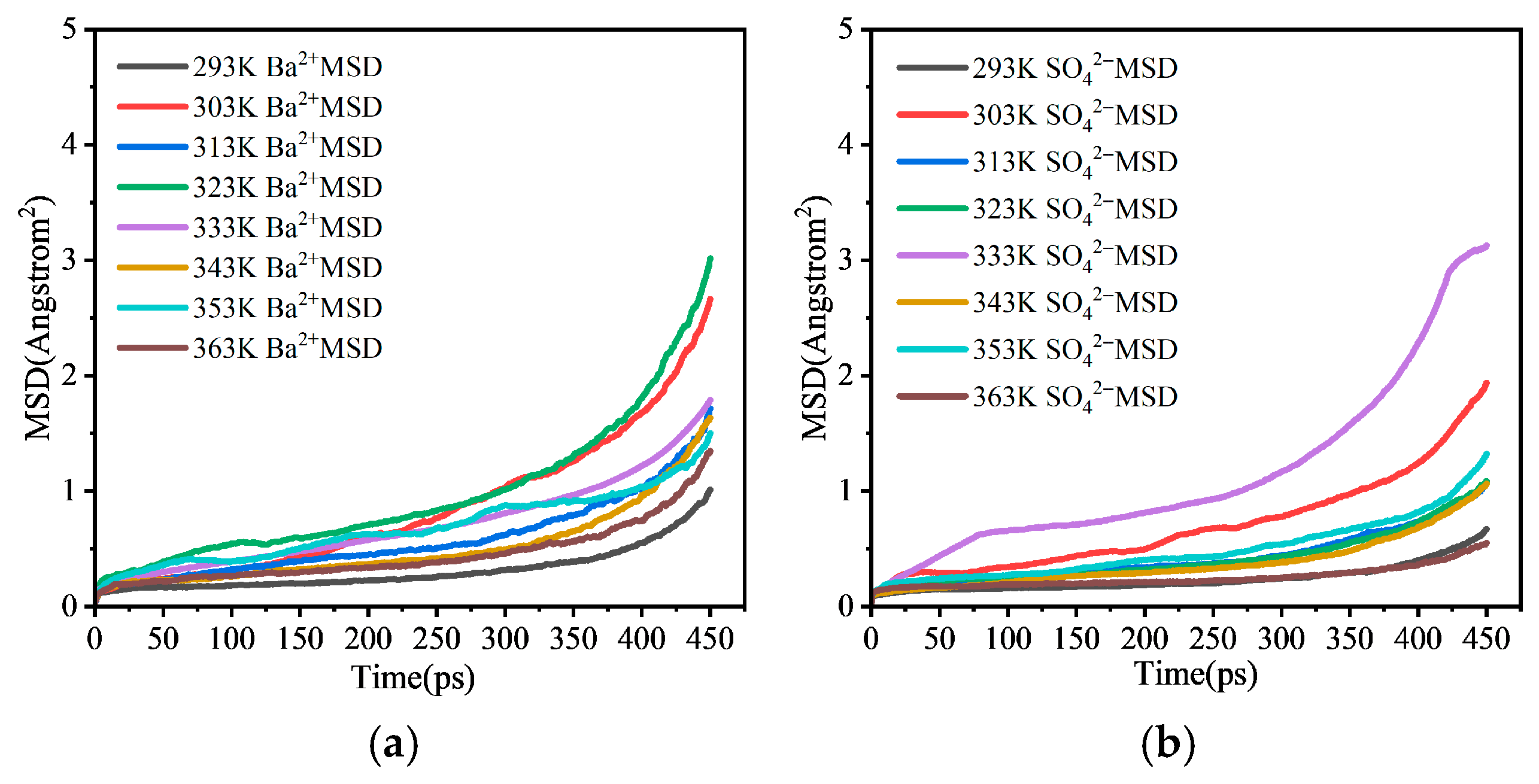

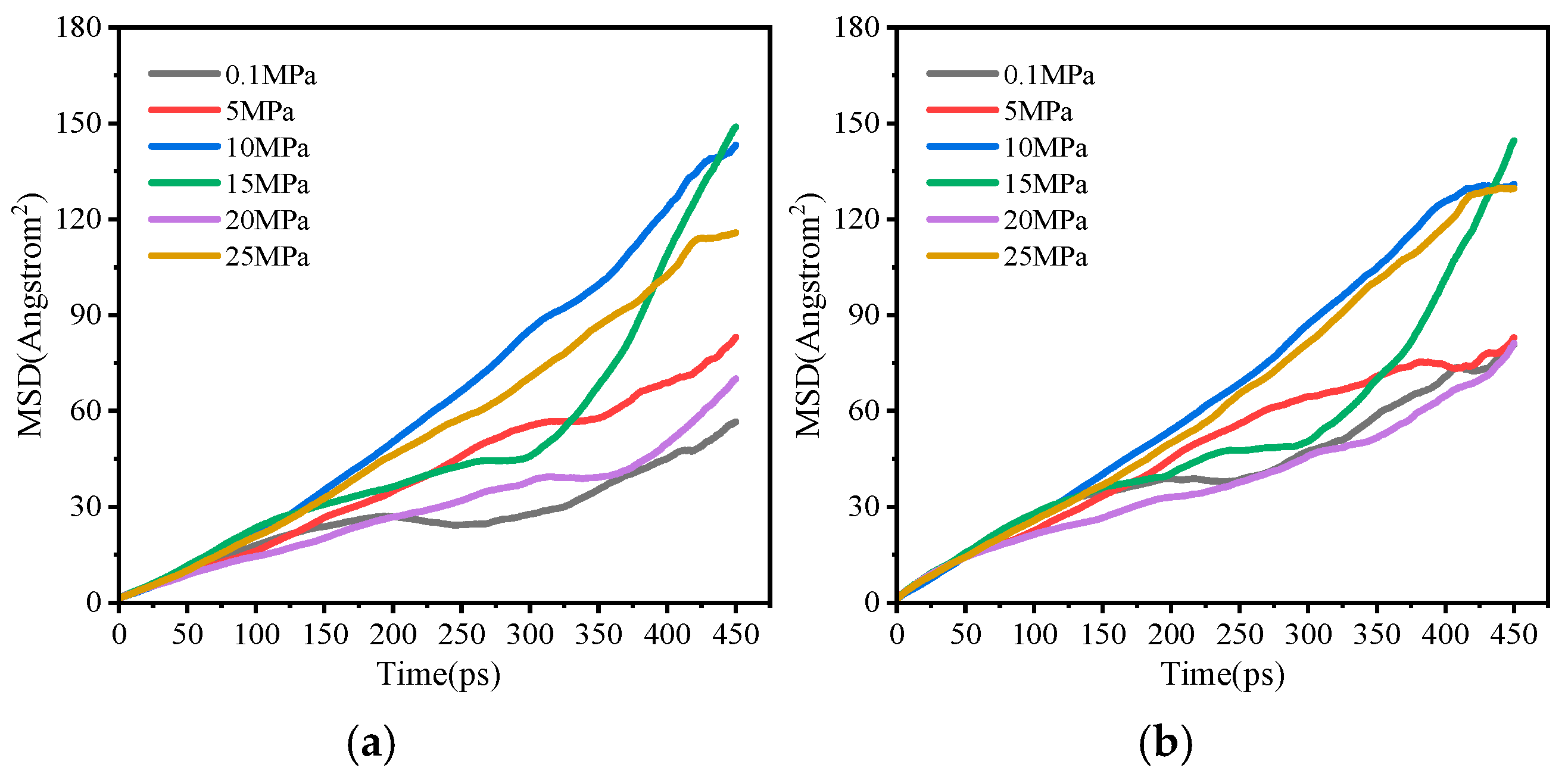

3.2.2. Influence of Different Factors on Ion Diffusion and Deposition Tendency

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Ba2+ and SO42− are the primary controlling ions for barium sulfate scaling. Increasing their concentrations significantly enhances scaling mass. Ca2+ may promote scaling at moderate concentrations (~5000 mg/L) by affecting interfacial properties, but excess (>8000 mg/L) causes competitive adsorption inhibition. High Na+ concentration (>70,000 mg/L) inhibits scaling via ionic strength effects. HCO3− concentration above 600 mg/L indirectly inhibits BaSO4 deposition by inducing CaCO3 coprecipitation.

- (2)

- Increased injection velocity promotes scaling by enhancing ion convection and mass transfer. Elevated injection pressure inhibits scaling by compressing pore space and reducing ion migration rates.

- (3)

- Molecular dynamics simulations reveal from a micro-scale perspective: increased ion concentration enhances deposition tendency by lowering MSD values and restricting diffusion; elevated temperature inhibits scaling by increasing MSD values and enhancing ion diffusion; pressure has an insignificant effect on ion diffusion behavior at the molecular scale.

- (4)

- Based on integrated findings, it is recommended to control the SO42− concentration in injected water below 300 mg/L for water injection development in low-permeability sandstone reservoirs. Optimizing the concentrations of Na+, Ca2+, and HCO3− to regulate ionic strength and competitive effects, while avoiding excessively high injection rates, can effectively mitigate the risk of barium sulfate scaling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, F.L. Research and Application of Advance Water Injection Technology in Low-Permeability Oilfields. China Pet. Chem. Stand. Qual. 2025, 45, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Tang, F.; Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Yao, R. Performance Evaluation of GX-S Nano-Based Oil Displacement Agent. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2022, 45, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.X.; Ren, K.F.; Luo, G.; Pan, D.C.; Chen, K. Synthesis and mechanism study of a novel barium sulfate scale inhibitor. Chem. Eng. 2024, 38, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y.Q.; Bai, H.L.; Ouyang, X.N.; Jiang, Y.M.; Pan, C.; Liang, Z.H. Preparation and performance evaluation of a novel barium sulfate scale inhibitor. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2021, 44, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z.Q.; Fan, J.C.; Guo, T.K.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, X.Q. Preparation and performance evaluation of barium sulfate scale inhibitor. Oilfield Chem. 2021, 38, 536–539. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.T. Research on Scale Prevention Technology in X block of Changqing Oilfield. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Research on Squeeze Scale Inhibition Technology for Barium-Strontium Scale Formation in LP Oilfield. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Dongying, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.J.; Ren, Z.; Yang, Y.S.; Ren, M. Preparation of Metal Oxides with Different Morphologies and Their Application in Industrial Catalytic Reactions. Acta Chim. Sin. 2021, 72, 2972–3001. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.C. Development and Prevention Mechanism Research of Barium/Strontium Sulfate Scale Inhibitor. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Dongying, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.Z. Study on Sulfate Scaling Model Based on Thermodynamic and Kinetic Principles. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.J.; Yu, X.Z.; Zhou, W.J.; Zhu, M.; Cui, X.Y. Study on the model of barium sulfate scaling effect on core permeability. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2017, 17, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Xian, H.; Li, T.; Yin, L.; Ma, Z.; Xing, C.; Feng, M.; Li, H.; Wang, K. Mechanism insight into the role of hydrogen on xylan hydropyrolysis by the combination of experiments and ReaxFF-MD simulation. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2026, 194, 107573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, I.; Dašić, M.; Jovanović, M.; Martini, A. Effects of Water Content on the Transport and Thermodynamic Properties of Phosphonium Ionic Liquids. Langmuir 2024, 40, 9049–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Song, D.; Du, W. Simulation and experiment of adsorption behavior of calcite, aragonite and vaterite on alpha-Fe2O3 surface. Comput. Mater. 2020, 182, 109762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dašić, M.; Stanković, I.; Gkagkas, K. Influence of confinement on flow and lubrication properties of a salt model ionic liquid investigated with molecular dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. E 2018, 41, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, X.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Q. Simulation of Free Water and Hydrated Calcium Silicate Pore Water Freezing Based on Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Mech. 2024, 41, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dašić, M.; Ponomarev, I.; Polcar, T.; Nicolini, P. Tribological properties of vanadium oxides investigated with reactive molecular dynamics. Tribol. Int. 2022, 175, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.Y. Reaction Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Thermal Decomposition Mechanisms for Multiple Energetic Plasticisers. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shabani, A.; Kalantariasl, A.; Abbasi, S.; Shahrabadi, A.; Aghaei, H. A coupled geochemical and fluid flow model to simulate permeability decline resulting from scale formation in porous media. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 107, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Yang, X.N. Molecular dynamicssimulation of wetting on modified amorphous silica surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 9078–9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Yang, X.N.; Qin, Y. Molecular dynamicssimulation of wetting behavior at CO2/water/solid interfaces. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 2252–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.F.; Cagin, T. Wetting of crystalline polymer sur-faces: A molecular dynamics simulation. J. ChemPhys. 1995, 103, 9053–9061. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Shu, Z.; Luo, P.; Zhu, S.; Liu, W. Molecular Simulation Study on the Adsorption of Hydrophobic Associating Polymers and Anionic Surfactants on Sandstone Surfaces. Bull. Polym. Sci. 2025, 38, 472–479. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhai, H.Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Effects of High-Pressure Fluids on Shale Fracturing and Fracture Development Processes. Acta Geophys. Sin. 2025, 68, 4851–4867. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.Z.; Ma, J.M.; Zhao, Y.C.; He, J.; Yu, J.J. Molecular simulation study on diffusion characteristics of waste cooking oil components in aged asphalt. New Chem. Mater. 2024, 11, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, J. Simulation of the relationship between calcium carbonate fouling and corrosion of iron surface. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 582, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L. Molecular Dynamics Study on Deposition Characteristics of Mixed Silica and Calcium Carbonate Fouling. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Electric Power University, Jilin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of CaCO3 Growth Characteristics on Its Fouling Surface in Solution. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Separdar, L.; Rino, J.P.; Zanotto, E.D. Crystal Growth Kinetics in BaS Semiconductor: Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Theoretical Calculations. Acta Mater. 2024, 267, 119716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Liu, D.; Luo, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Dong, Y. Studies on the dissolution mechanism of barium sulfate by different alkaline metal hydroxides: Molecular simulations and experiments. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 418, 126708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Gao, S.; Huang, X. Preparation of barium sulfate chelating agent DTPA-5Na and molecular dynamics simulation of chelating mechanism. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 34455–34463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, X. High-Performance Barium Sulfate Scale Inhibitors: Monomer Design and Molecular Dynamics Studies. Processes 2025, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Variable Ion | Concentration Gradient (mg/L) | Fixed Concentration of Other Ions (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ba2+ | 50, 100, 200, 400 | SO42− = 500, Na+ = 30,000, Ca2+ = 5000, HCO3− = 400 |

| 2 | SO42− | 100, 300, 500, 800 | Na+ = 30,000, Ca2+ = 5000, HCO3− = 400 |

| 3 | Na+ | 10,000, 30,000, 50,000, 70,000 | SO42− = 500, Ca2+ = 5000, HCO3− = 400 |

| 4 | Ca2+ | 2000, 5000, 8000, 12,000 | SO42− = 500, Na+ = 30,000, HCO3− = 400 |

| 5 | HCO3− | 200, 400, 600, 800 | SO42− = 500, Na+ = 30,000, Ca2+ = 5000 |

| Group | Inj. Velocity (mL/min) | Time (h) | Effluent [Ba2+] (mg/L) | Avg. [Ba2+] (mg/L) | BaSO4 Scale (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 480 | 485 | 3.1 |

| 1-2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 488 | ||

| 1-3 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 490 | ||

| 1-4 | 0.5 | 12.0 | 482 | ||

| 1-5 | 0.5 | 24.0 | 483 | ||

| 2-1 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 460 | 465 | 6.2 |

| 2-2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 468 | ||

| 2-3 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 470 | ||

| 2-4 | 1.0 | 12.0 | 462 | ||

| 2-5 | 1.0 | 24.0 | 463 | ||

| 3-1 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 440 | 445 | 9.3 |

| 3-2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 448 | ||

| 3-3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 450 | ||

| 3-4 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 442 | ||

| 3-5 | 2.0 | 24.0 | 443 |

| ID | Inj. Pressure (MPa) | Time (h) | Effluent [Ba2+] (mg/L) | Avg. [Ba2+] (mg/L) | BaSO4 Scale (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-1 | 5 | 0.5 | 450 | 455 | 8.3 |

| 7-2 | 5 | 1.0 | 458 | ||

| 7-3 | 5 | 12.0 | 452 | ||

| 7-4 | 5 | 24.0 | 451 | ||

| 8-1 | 10 | 0.5 | 460 | 465 | 6.2 |

| 8-2 | 10 | 1.0 | 468 | ||

| 8-3 | 10 | 12.0 | 462 | ||

| 8-4 | 10 | 24.0 | 463 | ||

| 9-1 | 15 | 0.5 | 470 | 475 | 4.1 |

| 9-2 | 15 | 1.0 | 478 | ||

| 9-3 | 15 | 12.0 | 472 | ||

| 9-4 | 15 | 24.0 | 471 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Xie, X.; Dou, M.; Wei, A.; Lei, M.; Ma, C. Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study on Influencing Factors of Barium Sulfate Scaling in Low-Permeability Sandstone Reservoirs. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031204

Yang H, Xie X, Dou M, Wei A, Lei M, Ma C. Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study on Influencing Factors of Barium Sulfate Scaling in Low-Permeability Sandstone Reservoirs. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031204

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Haien, Xuan Xie, Miao Dou, Ajing Wei, Ming Lei, and Chao Ma. 2026. "Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study on Influencing Factors of Barium Sulfate Scaling in Low-Permeability Sandstone Reservoirs" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031204

APA StyleYang, H., Xie, X., Dou, M., Wei, A., Lei, M., & Ma, C. (2026). Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study on Influencing Factors of Barium Sulfate Scaling in Low-Permeability Sandstone Reservoirs. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031204