1. Introduction

The detection of concealed objects on the human body through non-invasive methods to prevent the need for physical pat-downs is increasingly important in public safety and security screening systems. Their main goal is to enhance threat identification while preserving comfort and privacy. Among various wave-based modalities, acoustic methods offer advantages due to their ability to penetrate textile and soft-tissue layers, providing localized scattering signatures that may indicate the presence of foreign objects. However, challenges arise due to the complexity of wave interactions with anatomical heterogeneities, clothing layers, and environmental boundaries.

In recent years, various models and numerical strategies have been developed to simulate wave scattering phenomena involving penetrable or non-penetrable scatterers [

1,

2,

3]. In particular, multiple scattering problems have found applications across acoustics [

2], biomedical imaging, and non-destructive testing in various layered media [

3]. Several methods have been employed in the literature for modelling the scattering behaviour of cylindrical and arbitrarily shaped inclusions. For example, the distorted Born approximation has been applied to acoustic inverse problems [

4,

5]. At the same time, high-order boundary integral techniques have been used to solve Helmholtz-type formulations in media containing clusters of scatterers [

6,

7]. Other contributions highlight the effectiveness of Krylov subspace solvers and Fourier-based truncation schemes in accelerating convergence and managing computational complexity [

8,

9,

10]. Previous research has explored 2D and 3D models for acoustic scattering using numerical solvers and inverse problem formulations. Bibicu et al. [

11] conducted extensive simulations on the low-frequency acoustic detection of hidden objects using a simplified human body model, analysing the effects of various boundary conditions, including rigid and absorbing enclosures. Their findings demonstrated the sensitivity of the backscattered field to material composition and wave frequency, highlighting the potential of passive or active acoustic detection in confined environments.

This study tackles the challenge of border security by quickly detecting drugs, explosives, weapons, and illicit goods hidden on people. To do this, it models a simplified human body. This model consists of penetrable cylindrical acoustic scatterers representing bone, muscle, fat, and textile layers. Concealed inclusions are embedded within the model to mimic non-biological items (e.g., steel, salt, PVC), and simulations are conducted across a wide frequency range (20 Hz–1000 Hz). The PVC cylinders were placed on the body surface to mimic how smugglers or malicious individuals conceal illicit items. Simulations are performed using the µ-diff MATLAB R2023a toolbox [

12], which offers a fast and accurate solver for multiple scattering problems through boundary integral equations and spectral Fourier-based discretization.

The main goal of this work is not to propose a new boundary integral formulation but to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method when applied to a common and widely used boundary integral equation formulation. The single- and double-layer operators were selected due to their simplicity and computational efficiency. The numerical framework enables efficient modeling of both wave propagation and wave-object interactions in complex geometries, including confined domains with reflecting or absorbing walls. The numerical experiments and applications presented in the manuscript are deliberately restricted to frequency ranges that avoid the problematic interior resonance frequencies. Within this regime, both the single- and double-layer formulations are well-posed and yield unique, stable solutions, as confirmed by our numerical observations. Consequently, the reported results are not affected by the non-uniqueness issues associated with resonant frequencies. We are aware that our approach can be directly applied to well-posed alternatives, such as combined-field integral equations. However, the choice of boundary integral operators in our work was also influenced by experimental considerations. The system is expected to provide a decision within a short timeframe.

The main contributions of this paper include the following:

- -

Introduce a low-frequency regime, where the wavelength is large compared to the characteristic size of the investigated features, which is motivated by several considerations. First, low frequencies reduce sensitivity to noise, which enhances the robustness of the detection procedure. Second, from a numerical standpoint, the low-frequency regime avoids dispersion and pollution effects that typically affect high-frequency simulations, ensuring stable and reliable solutions within the adopted computational framework.

- -

Conduct a simulation experiment using a simplified dummy human body. This body will have integrated concealed objects represented as a cluster of penetrable tangent circular cylinders. These cylinders have acoustic properties that mimic muscle, fat, bone, clothing, and PVC.

- -

Propose a detection mechanism that relies on the contrast between the material properties of the target and the surrounding medium, i.e., an impedance mismatch. At low frequencies, the scattered response is primarily governed by this contrast rather than by resonant or geometric effects. As a result, the presence of the target can be inferred from measurable variations in the field induced by the impedance mismatch, which makes the detection strategy robust and less sensitive to modeling uncertainties.

While previous work [

11] examined the human body in enclosures, this study is the first to introduce penetrable tissue models combined with concealed high-contrast inclusions in an absorbing cabin environment. By analysing the spatial patterns and amplitude modulations in the acoustic field, this study contributes to the development of non-invasive detection systems for use in enclosed spaces such as airport checkpoints, transport cabins, or industrial environments.

This paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 details the materials and methods, including the mathematical model of the scattering problem and the associated geometry.

Section 4 presents the results, while

Section 5 discusses them. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Related Works

Literature analysis revealed a limited number of research papers focused on the proposed theme. Many papers addressed either multi-scatterer 2D algorithms, human tissue modelling in 3D, or room/enclosure acoustics. However, few combined a two-dimensional multi-scatterer formulation of a dummy human-shaped model within a bounded enclosure with carefully modelled boundary conditions across a low frequency range. The Boundary Element Method (BEM) is a classic, widely used approach for exterior acoustic scattering, as it reduces problem dimensionality and naturally enforces radiation conditions [

13,

14]. BEM is a good baseline for 2D Helmholtz formulation and for references on singular integrals, quadrature, and inverse problems. Hybrid BEM–FEM (Finite Element Method) and improved FEM/BEM coupling methods have been developed to address interior–exterior coupling and complex material behaviour like elastic shells and solid–fluid interactions. Recent surveys and numerical studies reveal trade-offs between domain and boundary methods for coupled problems [

15,

16]. Multi-scatterer problems (e.g., many obstacles or inclusions) are often handled via multiple-scattering series, T-matrix methods, or boundary-integral formulations accelerated with the Fast Multipole Method (FMM). Fast high-order and FMM-accelerated boundary element method implementations for 2D and 3D scattering are well-established and essential for simulating numerous scatterers or at high frequencies [

17]. These methods are considered relevant if the human body is approximated by numerous sub-elements like limbs, a torso, and clothing, or if multiple reflecting objects are present within the enclosure.

While not directly related to applications involving <1000 Hz acoustic waves, several studies are related to security screening research, particularly in hidden object detection and imaging technologies. Thus, Lee et al. [

18] utilize ultrasonic waves to nondestructively detect and characterize concealed weapons and internal contents like liquid chemical agents. They analyzed the propagated wave signals outside sealed containers. This highlights ultrasonic sensing’s potential as a portable and safer alternative to radiographic techniques in security and forensic applications. Win et al. [

19] investigated shape detection of objects behind thin media using kHz-range ultrasonic sensors operating just above the low audible/ultrasonic range. Their experiments demonstrated that inexpensive transducers can extract shape information from objects concealed behind a thin medium. This practical study revealed echoes and reflections of acoustic waves from hidden objects.

Several recent studies model 3D wave propagation and scattering within human tissues for medical imaging and tomography. These models predominantly utilise high-frequency domains. These works cover frequency-dependent material properties, attenuation, and complex internal scattering. While primarily 3D, these works offer essential material models and validation approaches for adapting to a 2D idealised human model [

20,

21]. There is an emerging 2D simulation study specifically investigating active detection of hidden items based on scattering from dummy human bodies at low frequencies [

11]. This study examined the role of boundary conditions and enclosure effects on the human-scattering problem. Previous 2D detection studies prioritised sensitivity to boundary conditions. They explicitly model the impedance and modal structure of the enclosure and quantify their impact on scattering signatures [

22]. The authors [

23] have significantly contributed to the development of fast BEM techniques based on H-matrices, which provide competitive alternatives to the FMM.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mathematical Model of the Scattering Problem Under Simplifying Conditions

To simulate the interaction between time-harmonic acoustic waves and penetrable objects placed on or near the human body, we employed the open-source MATLAB R2023a toolbox µ-diff [

12,

24,

25,

26]. The µ-diff algorithm is based on boundary integral equations (BIE) combined with spectrally accurate Fourier-based discretization for cylindrical geometries. The simulations aim to reproduce realistic security-screening conditions, accounting for the presence of high-contrast inclusions (e.g., metallic items or illicit substances) that may be concealed on the body surface or underneath garments.

Let

denote the union of M disjoint circular disks with center

and radii

. An incident wave,

, is assumed to be a plane wave:

where

is the spatial coordinate,

is the unit vector that indicates the direction of propagation, β is the incidence angle and k is the wavenumber. The acoustic wavefield is governed by the following transmission problem, which is reformulated using boundary integral equations suitable for spectral discretization:

Here, and denote the interior and exterior acoustic fields, respectively. The domain represents the union of the penetrable scatterers, while denotes the unbounded exterior region. The interface between the two media is denoted by . The parameters and are the wavenumbers inside and outside the scatterers, respectively. The operator denotes the Laplacian, and represents the normal derivative with respect to the outward unit normal vector n on . The last equation in system (2) represents the Sommerfeld radiation condition at infinity, which ensures the uniqueness and physical relevance of the scattered field in the unbounded domain. Here, denotes the Euclidean norm, and is the gradient operator.

The exterior field

and interior field

are represented as single-layer potentials, denoted by

:

where

are densities,

are Green functions of Helmholtz equation in exterior/interior domain, and Γ is the boundary of the collection of scatterers. Here,

, and

denotes the boundary integration element. Green functions are defined as follows, where

denotes the Hankel function of the first kind, and zero order and

is the Euclidean distance between the points x and y:

Imposing the continuity of the total field and the normal component of the flux across each interface leads to the following system of integral equations on Γ:

where

denotes the normal derivative of the single-layer operator in the exterior and interior domains, respectively:

The total acoustic field in the exterior is then reconstructed as the sum of the incident wave

and the scattered field

:

The boundary integral equations are discretized using a truncated Fourier series representation of the surface densities ρ±, exploiting the circular geometry of the inclusions. This spectral approach, implemented in the µ-diff toolbox, ensures high numerical accuracy and computational efficiency, particularly for problems involving large numbers of cylindrical scatterers.

The following simplified conditions are used:

- -

The Sommerfeld radiation condition still applies, and the field varies more slowly. This slower decay is due to the small , meaning the waves spread out more slowly, i.e., weaker scattering. However, different materials directly affect the acoustic propagation. It is worth noting that in our idealised model, real tissues have attenuation. However, to simplify calculations, we assume a real k instead of a complex one.

- -

The attenuation coefficient is only considered for the absorption wall included in the cabin.

- -

At low frequency, the velocity gradients are smaller, flux differences are less pronounced, and the boundary flux is affected to a lesser extent.

- -

Different densities of acoustical media are generally independent and correspond to the selected tissues with distinct physical properties. These differing densities modify the flux condition and ensure impedance contrast effects.

- -

It is well-known that the impedance contrast/flow of acoustic energy, Q factor, and damping are intrinsically linked. Within a cabin with rigid walls, impedance contrast, a high Q factor, and low damping work together to allow modal energy to persist effectively, masking small disturbances. In the presence of an absorbing wall, the Q factor decreases, causing the system to lose energy quickly, and the modes become broader and less pronounced. Existing objects in the acoustic field further perturb the modes by altering local pressure gradients. Following these related mechanisms, the proposed approach explicitly accounts for impedance contrast through the density ratio, which represents the dominant physical mechanism governing the observed scattering behavior.

By modelling the materials as fluids, this dominant impedance mismatch is captured, which is the crucial physical mechanism behind the detection strategy.

3.2. Acoustic Scene Geometry

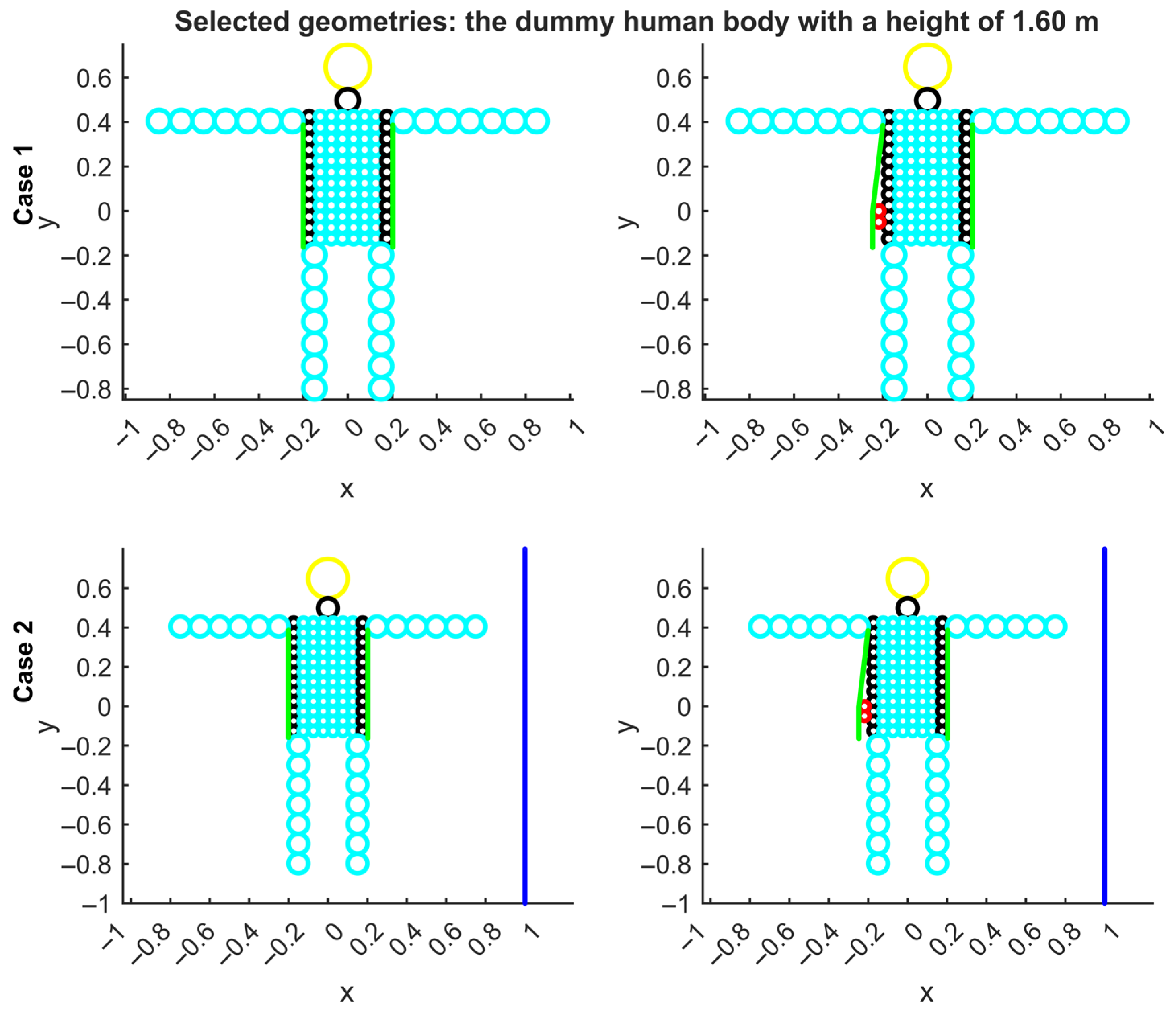

The geometrical configuration of the simplified human model and the positioning of hidden items are displayed in

Figure 1, which also includes the variation between reflective and absorbing boundary conditions. The acoustic cabin is modelled as a rectangular enclosure with dimensions 6 m (length) × 2.5 m (width). The walls of the cabin are treated as either rigid (reflective) or partially absorbing, depending on the simulation scenario, allowing analysis of boundary effects on wave propagation and scattering behaviour. The absorbing walls are modelled using 900 cylindrical elements, each with a radius of 0.1 cm, to represent the acoustic properties of commercial polyester (SD) foam. These cylinders are arranged to simulate a porous, sound-absorbing surface, enabling analysis of wave attenuation and scattering pattern alterations within the enclosure.

We used a simplified cylindrical model of the human body that closely resembles the real anatomical structure. The dummy human body model, constructed from a set of acoustic cylinders, represents major anatomical components using simplified geometries and material approximations. The example provided depicts a person 1.60 m tall, and the vertical sum of the cylinders’ diameters corresponds to this height. Furthermore, we have attempted to replicate the average size of the main anatomical structures in the best manner possible. The configuration includes:

- -

One central cylinder with radius r_head = 10 cm, simulating the head (modelled as bone);

- -

One cylinder with radius r_neck = 5 cm, representing the neck (modelled as fat);

- -

Fourteen cylinders (2 × 7) with radius r_arm = 5 cm, simulating the arms (modelled as muscle);

- -

Twenty-four cylinders (2 × 12) with radius r_body = 2.5 cm, representing body fat, and seventy-two cylinders (6 × 12) with the same radius, representing body muscle;

- -

Fourteen cylinders (2 × 7) with radius r_leg = 5 cm, modelling the legs (modeled as muscle).

Each cylindrical element is assigned acoustic properties corresponding to its biological tissue type (fat, muscle, or bone). This simplifies the model while still providing a functional representation for acoustic wave scattering analysis.

A total of 550 cylinders, each with a radius of 0.1 cm, are used to simulate the effect of flax fabric, representing the clothing layer on the body model. These cylinders are distributed over the surface of the simplified human body model to approximate the acoustic impact of woven textile material. The centre-to-centre spacing of the clothing cylinders is 0.1 cm because they are tangent to each other reciprocally. The collective response of these closely spaced cylinders reproduces the macroscopic acoustic behavior of a thin, porous fabric layer, with scattering primarily governed by the overall impedance contrast and thickness, rather than by fine microstructural details.

Fluid-equivalent models are commonly used in low-frequency ultrasound and acoustic scattering studies where the goal is detection rather than detailed characterisation of internal elastic wave phenomena. The biological tissues (bone, muscle, fat) and the investigated objects (e.g., PVC) are modeled as penetrable acoustic scatterers represented by fluid equivalents, and support only compressional (longitudinal) waves. This approximation is justified by the low-frequency range considered in this study. At frequencies between 20 and 1000 Hz, the corresponding wavelengths in soft tissues and in typical solids of interest are significantly larger than the characteristic dimensions of the modeled structures. In this regime, shear wave effects are negligible in the scattered acoustic field, and the interface response is dominated by impedance contrast. At low frequencies, the scattering behaviour is mainly governed by the density and bulk modulus differences between the scatterer and the surrounding medium.

To simulate hidden objects, 2, 3, or 4 cylindrical inclusions with a radius of r3 = 2.5 cm were embedded within the body model. These cylinders are assigned the acoustic properties of PVC, representing concealed non-biological items such as plastic contraband or foreign objects.

The simulations were performed at a range of discrete frequencies: 20, 50, 125, 160, 300, 500, and 1000 Hz. These frequencies were selected to cover low to mid-range acoustic bands, allowing analysis of frequency-dependent scattering behaviour and the sensitivity of detection to object size, material contrast, and environmental absorption.

4. Results

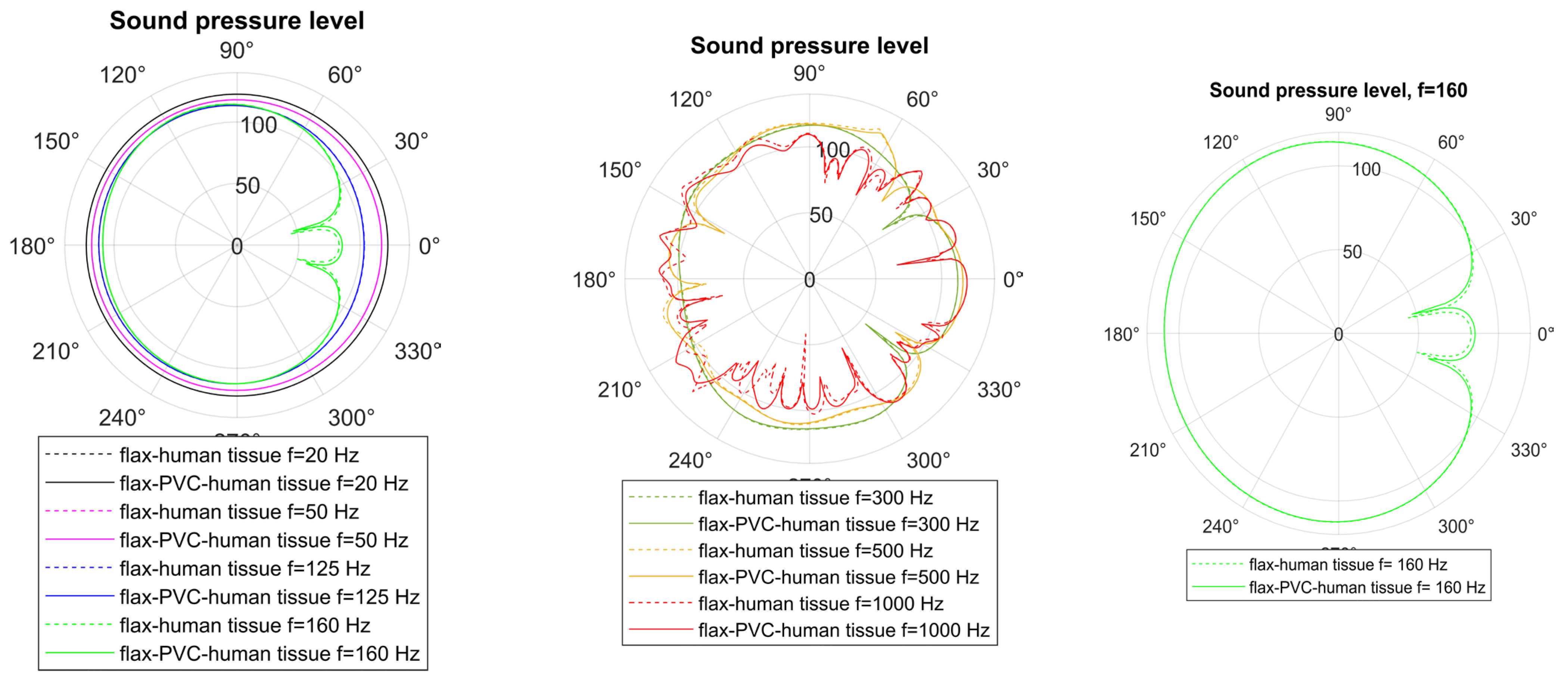

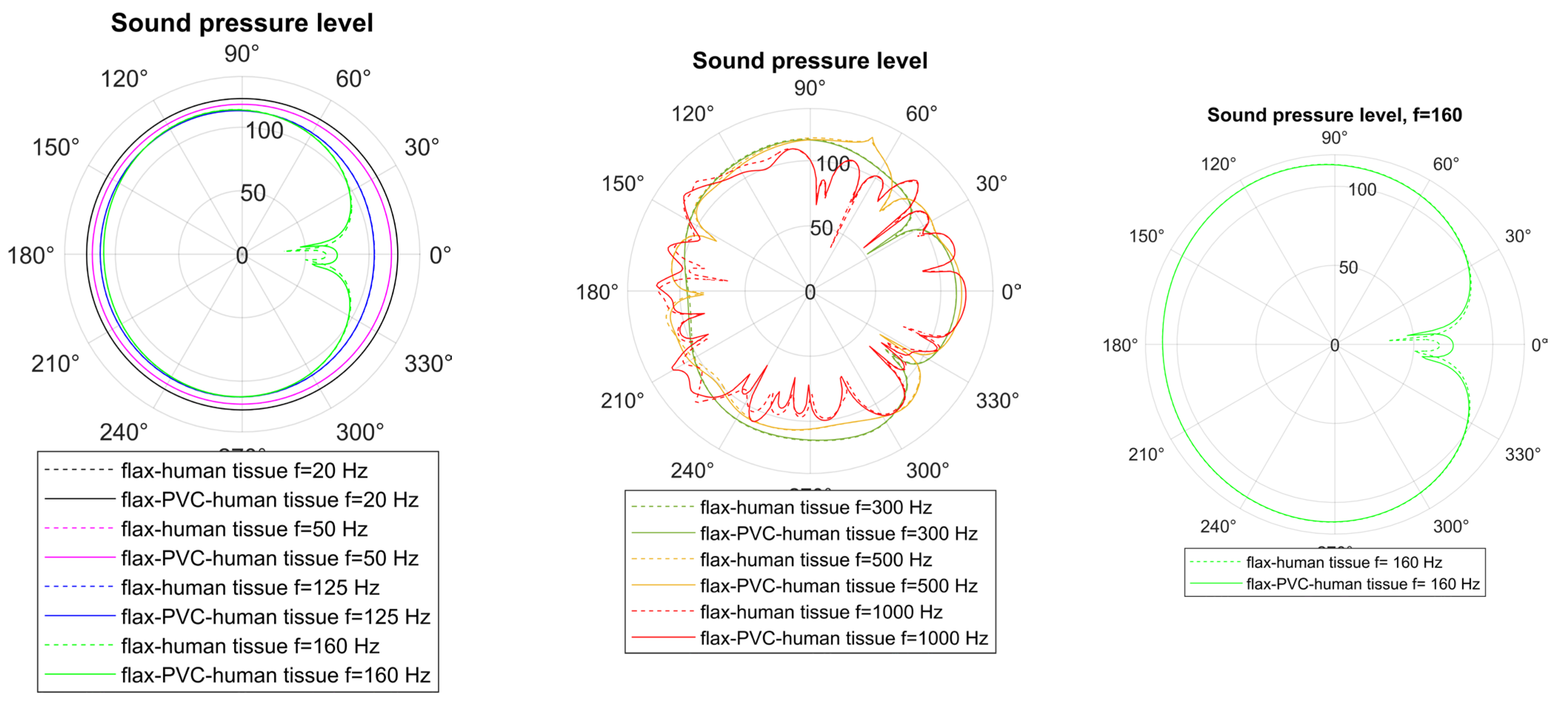

The simulation results primarily analyse the sound pressure level (SPL) distribution surrounding the human body model and its variation at a 1 m distance due to the presence of concealed objects. Polar plots of the scattered field reveal differences between the baseline body model and configurations containing embedded PVC inclusions, with pronounced effects observed at frequencies around 160 Hz.

Table 1 presents typical acoustic (longitudinal) sound speeds, c, and mass densities, ρ, for the materials used in simulations. For the frequency range 20–1000 Hz, these properties are frequency-independent for homogeneous materials.

Table 2 presents the technical indicators of the commercial polyester (SD) foams employed in the simulations.

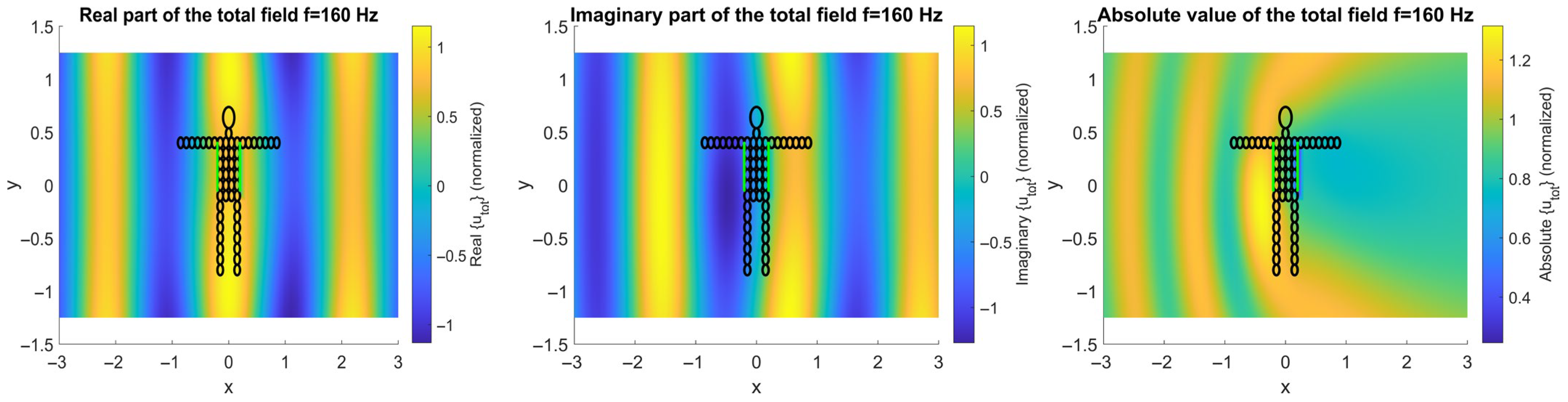

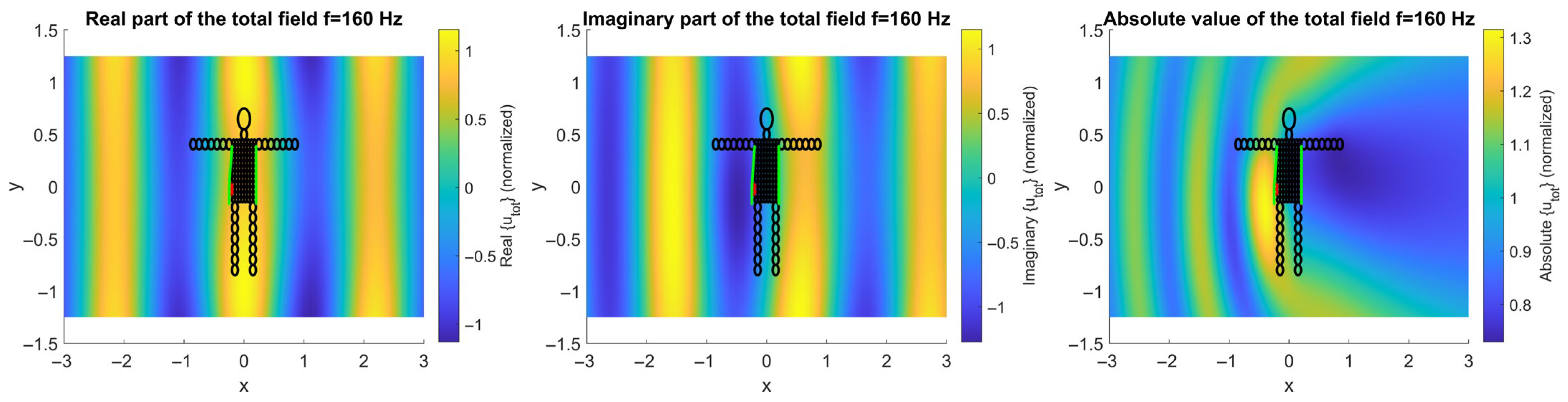

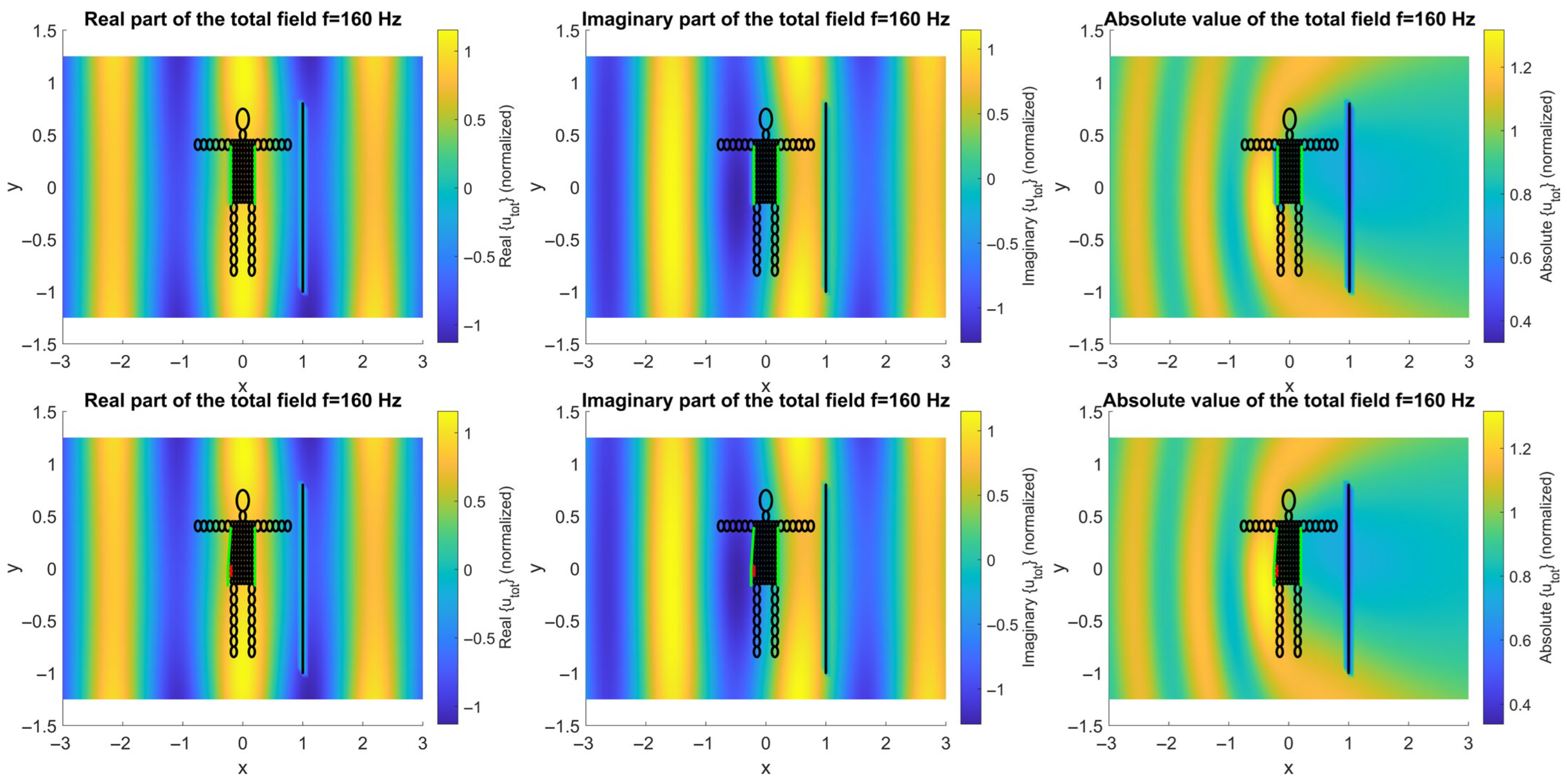

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the computed acoustic field distributions for the simplified human body model subjected to an incident plane wave at a frequency of 160 Hz. The visualizations include the real part, imaginary part, and absolute magnitude of the total acoustic field, with and without the presence of hidden objects. The color maps show the complex total field

, defined in Equation (7), at a frequency of 160 Hz. Since the incident plane wave is defined with unit amplitude, the field values are reported in normalized units.

In

Figure 2, the simulation is performed without any enclosure wall. The top row shows the case where the body is dressed with a clothing layer (modelled using flax material). The bottom row adds two embedded PVC cylinders to simulate hidden items. The comparison reveals clear scattering and interference effects due to the presence of foreign inclusions, especially visible in the changes in field amplitude and phase around the embedded objects.

Figure 3 presents the same configuration but with an absorbing wall placed at the right-hand side of the scene. The absorbing wall is modelled using a dense distribution of polyester-based cylindrical elements, mimicking acoustic treatment panels. Compared to the free-field case, the presence of the absorbing wall reduces field reflections, which significantly alters the global field pattern. While hidden items still generate localized scattering, the overall amplitude of reflected waves is lower due to boundary absorption, which may improve the detection clarity in specific scenarios.

Data in

Figure 4 presents the sound pressure level (SPL) distribution for the simplified human body model, representing a person with a height of 1.60 m. The acoustic enclosure features rigid, fully reflective walls with no absorption. Simulations were performed at discrete frequencies of 20, 50, 125, 160, 300, 500, and 1000 Hz to evaluate frequency-dependent scattering effects. At 160 Hz, the SPL distribution exhibits only a marginal variation, making it challenging to distinctly identify the presence of concealed objects. In Case 1, without an absorbing wall, the SPL curves for different frequencies and materials nearly overlap. This suggests no significant change in measured sound pressure level. Within the analysed frequency range, the materials create marginal impedance perturbations. Consequently, the acoustic impedance contrasts are minimal, and absorption is weak at these frequencies.

Data in

Figure 5 presents the sound pressure level (SPL) distribution for the simplified human body model, representing a person with a height of 1.60 m, inside an acoustic enclosure featuring an absorbing wall. Simulations were conducted at multiple frequencies of 20, 50, 125, 160, 300, 500, and 1000 Hz to evaluate frequency-dependent scattering effects. It is well-known that the human body vibrates in multiple modes when placed in an acoustic field. Frequencies around 60–120 Hz might have higher coupling due to thoracic resonance. Frequencies around 150–400 Hz are more likely to excite skull/upper body structural modes [

28]. At 160 Hz, the SPL distribution exhibits a distinct variation attributable to the presence of concealed objects, enhancing the detectability of hidden PVC inclusions within the model. This difference suggests that absorption by the enclosure walls improves the acoustic signature of concealed items, facilitating more effective identification compared to non-absorbing conditions. Even unrelated to this study, we can speculate that this frequency might relate to human body vibrational modes. Further investigation is needed, but this hypothesis could expand the proposed methodology’s application to new medical fields.

The excitation signal used in this study is a linear frequency-modulated chirp spanning the frequency range 20–1000 Hz. A source level of 100 dB was selected to ensure adequate penetration and measurable scattered fields after interaction with clothing layers and biological tissues. Also, if we examine the phon (i.e., perceived loudness level)–dB relationship at low frequencies, based on equal-loudness contours, a much higher dB SPL is required to achieve the same phon value. From a human perspective, this extremely high sound level, exceeding 100 dB, is harmless. However, from a physical perspective, an absorption wall was incorporated into the experiment.

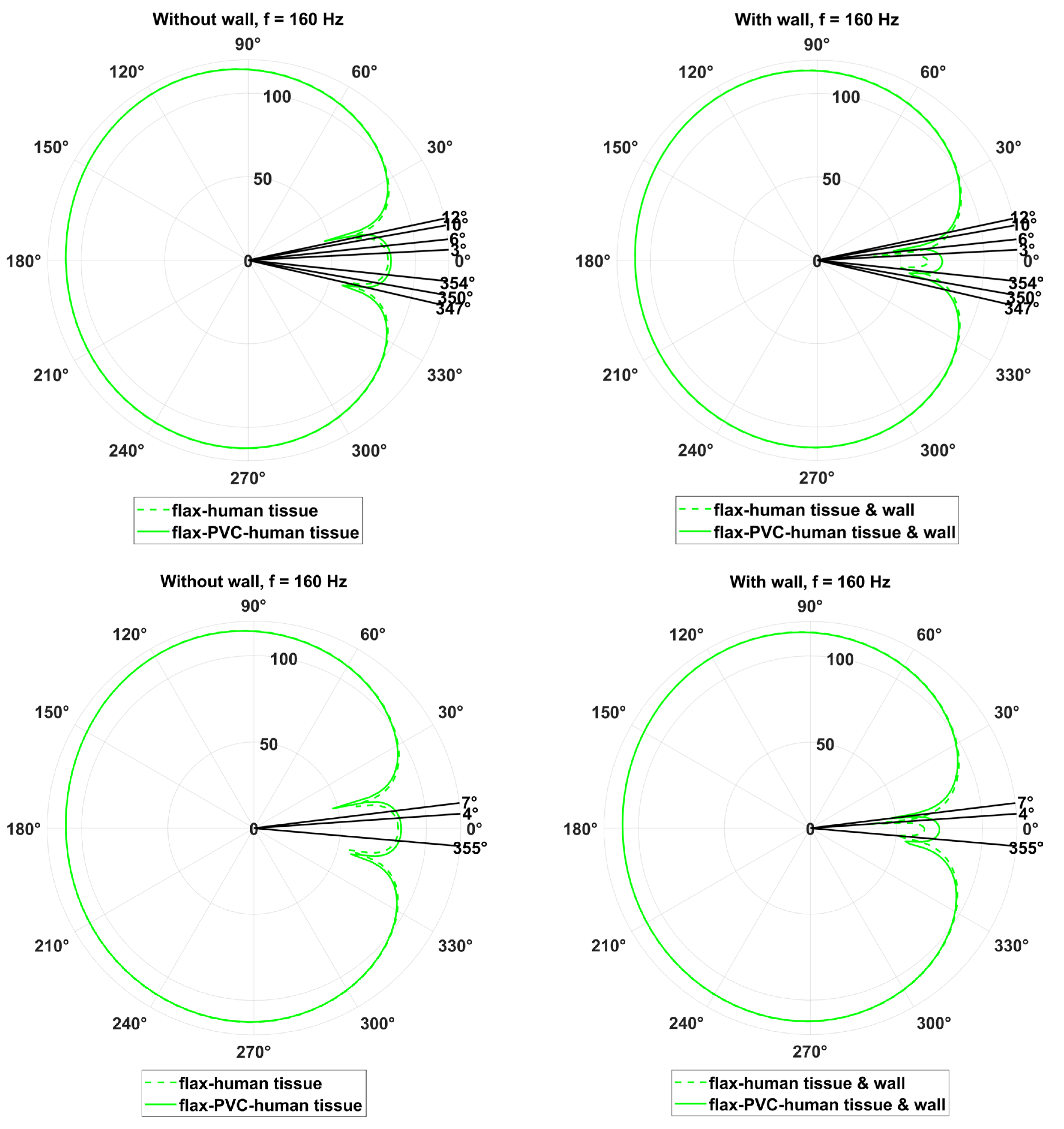

The absolute difference between SPL values in particular theta angles, presented in

Figure 6, were calculated as follows:

where

is the baseline SPL value of flax-human-tissue (Case 1) and

represents the SPL value of flax–PVC–human tissue (Case 2). The results are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3 presents the absolute differences in SPL values between the baseline, i.e., flax-clothes-based human tissue model denoted as Case 1, and scenarios involving PVC hidden cylinders, denoted as Case 2, measured at selected angles at 160 Hz. This analysis highlights the impact of the number of concealed objects on acoustic scattering and wave redirection.

We have also investigated whether the 160 Hz frequency matches a cabin’s modal frequency. Room modes occur when sound waves reflect and interfere, forming standing waves at specific frequencies. For a rectangular room, the modal frequencies are determined by:

where c is the speed of sound in air;

,

, and

are mode numbers (0, 1, 2, …) in each direction; and L, W, and H are room dimensions (length, width, height).

In the case of lengthwise mode (x-direction): . This results in possible frequency multiples of 57.16 Hz, 85.74 Hz, 114.32 Hz, 142.9 Hz, and 171.5 Hz. The 160 Hz frequency is close to 142.9 Hz and 171.5 Hz, so it might resonate weakly.

For the widthwise mode (z-direction): , with possible multiples of 114.3 Hz and 171.5 Hz. In this case, 160 Hz does not perfectly match but is close to 171.5 Hz, so some marginal coupling may occur.

For the heightwise mode (y-direction and assuming H = 2.5m): . The possible multiples are 137.2 Hz, 205.8 Hz. In this case, the frequency of 160 Hz does not align with these values but sits between nearby harmonics.

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of the Number of Hidden Cylinders

A clear trend emerges in which the SPL differences increase with the number of hidden cylinders. Specifically, in the scenarios with two hidden PVC cylinders, the average SPL absolute differences are relatively moderate, at 4.62 and 12.69, respectively. However, in the cases involving four hidden cylinders, the average SPL absolute differences rise substantially, reaching 6.92 and 18.42. This increase suggests that the presence of more obstacles significantly alters the propagation of acoustic waves, likely due to enhanced scattering and reflection. Such findings indicate that configurations with more hidden elements may be more easily detectable through acoustic backscattering analysis.

5.2. Effect of the Absorption Wall

The introduction of an absorbing wall (as in Case 2) results in notably higher SPL differences compared to the corresponding cases without absorption (Case 1). This confirms that the absorbing boundary condition contributes to the dissipation of incident energy, thereby amplifying the SPL contrast between tissue-only and object-hidden scenarios. The impact is particularly strong in the Case 2 study, where both the number of cylinders and the absorbing wall contribute to the highest observed SPL differences.

In the rigid-wall configuration, the cabin boundaries are modeled as acoustically hard surfaces by imposing a sound-hard (Neumann) boundary condition, which corresponds to perfectly reflective walls with zero normal particle velocity and a reflection coefficient equal to one. The global sound field is controlled primarily by cavity resonances. Local scattering by hidden objects is partially masked by dominant reflections filling the cavity and by cavity geometry.

In the partially absorbing configuration, the cabin walls are modeled using an impedance (Robin) boundary condition, which accounts for energy dissipation at the boundary. The impedance is chosen to represent a uniform, frequency-independent wall absorption corresponding to a specific absorption coefficient (

Table 2 and ref. [

27]). In this scenario, reflected energy is reduced, and more of the field is influenced by local scattering from internal objects and absorption, which eliminates cavity echo buildup. Consequently, the wavefield around a dummy human body becomes object-sensitive rather than cavity-dominated as internal reflections no longer overpower scattering effects. Our investigation related to whether the 160 Hz frequency matches a cabin’s modal frequency confirms that the cabin has no significant influence. In a cabin with rigid walls, the cavity quickly fills with a highly reverberant standing-wave field. This field overrides any small modifications caused by internal objects. However, when an absorbing wall is added, the reverberant energy is largely suppressed, and the acoustic field becomes more spatially localised. The presence of the hidden objects causes variance in SPL values because the cavity’s natural modes no longer dominate the pressure distribution.

5.3. Angular Distribution Observations

The angular distribution of SPL differences reveals that the most significant deviations occur at small forward angles, specifically in the ranges 0–12° and 347–360°. These angles correspond to the direction of wave propagation, where strong reflections and interference patterns result in elevated SPL values. This behaviour suggests that hidden objects have a greater impact on the acoustic field in the forward direction, particularly when the object configuration leads to constructive interference.

An analysis of SPL absolute differences at specific angular positions (θ = 4°, 7°, and 355°), as shown in

Figure 6 and highlighted rows in

Table 3, reveals a marked contrast between scenarios with and without the presence of an absorbing wall. In Case 2 (with the absorbing wall), these angles consistently show significantly higher SPL absolute differences for the two-cylinder configuration, reaching up to 37.55 at 4°, 24.39 at 7°, and 21.49 at 355°. In contrast, Case 1 (without the wall) yields much smaller differences at the same angles, approximately 1.96, 2.54, and 1.96, respectively. This pronounced disparity highlights the amplifying effect of the absorbing boundary on acoustic field perturbations caused by hidden objects. The absorbing wall reduces global reflections, thereby increasing the contrast between the baseline and perturbed configurations. As a result, concealed items become more detectable at specific forward and near-forward angular positions.

These angular positions likely correspond to zones of constructive interference, where acoustic path differences amplify SPL sensitivity to internal structural variations. This observation underscores the critical role of boundary condition design in acoustic sensing environments. It also suggests that targeting angular windows with high differential responses, such as θ = 4°, 7°, and 355°, can significantly enhance detection performance in practical applications. Lower SPL differences are observed at other angular positions, particularly at side angles (e.g., 90°, 120°) and in the backscattering region (e.g., 160–180°). These regions are characterized by reduced acoustic radiation levels, especially in scenarios with symmetric geometries or the presence of absorbing boundaries. The observed attenuation in the backscattering domain is consistent with theoretical expectations for plane wave interactions, where most acoustic energy propagates forward rather than reflecting backward.

5.4. The Effect of Cabin Modal Frequencies

The 160 Hz frequency does not precisely match any primary modal frequencies but is close to several harmonics, especially around 171.5 Hz. This could potentially create a slight resonant response within the cabin. The results reinforce several important principles:

- -

The width and strength of the main lobe increase as the number of hidden items increases.

- -

Backscattering levels are generally lower for plane waves, especially with absorbing surroundings.

- -

Detection becomes more efficient when the hidden structure significantly disturbs the wavefront, as seen in higher SPL differences.

- -

A narrower main lobe and reduced side lobes are desirable for achieving better directional sensitivity in detection applications.

These findings offer practical guidance for designing acoustic detection systems and highlight the significance of wave-object interaction analysis in situations involving concealment structures.

This work uses the most appealing variant of a 2D model where scatterers are represented as infinitely long cylinders. This idealised approach is simpler to use in a simulation environment where an obstacle consists of multiple objects perceived as continuously heterogeneous fluid equivalents without compromising the scattering mechanisms. This configuration remains unchanged along the out-of-plane direction. This approximation is valid when the dominant acoustic interaction occurs in a plane perpendicular to that dimension. When the out-of-plane dimensions of the body, clothing, and objects vary slowly along that direction, and the assumption of spatially invariant mass density throughout all space holds, the scattered field can be reasonably approximated as quasi-two-dimensional. This means edge and end effects are minimal, and the infinite-cylinder assumption accurately describes the dominant scattering mechanisms.

We acknowledge that this approximation would no longer be valid at higher frequencies, where shear and mode-conversion effects become non-negligible.

6. Conclusions

This work presented the first study addressing a 2D numerical investigation of acoustic wave scattering involving a simplified human body model within an enclosed cabin, using the µ-diff MATLAB toolbox. The human model was constructed from cylindrical elements approximating biological tissues and included PVC inclusions to simulate concealed non-biological objects. The boundary condition assures the penetrable scattering condition. The simulation results revealed that:

- -

The number of hidden items influences the scattered acoustic field. Increasing the number of PVC inclusions led to higher differences in SPL values, suggesting enhanced detectability through backscattering analysis.

- -

Absorbing boundary conditions amplified SPL contrasts, especially in scenarios with multiple hidden objects. The presence of an acoustic absorbing wall reduced global reflections and improved the localization of scattering caused by concealed items.

- -

Angular analysis revealed that SPL differences were most pronounced in the forward direction (0–12° and 347–360°), where wave–object interactions generated strong constructive interference. In contrast, backscattering angles exhibited minimal variation, indicating lower energy radiation in those directions for plane wave incidence.

- -

The cabin’s fundamental modal frequencies have no significant influence on the backscattering frequency used for hidden-item detection, although they can generate a weak resonant response inside the cabin.

These findings confirm that both object configuration and enclosure boundary conditions play a crucial role in the acoustic signature of the scene. By combining numerical simulation with directional SPL analysis, this work contributes to the development of wave-based, non-invasive detection techniques applicable in enclosed environments such as transport cabins or security checkpoints. Our analysis takes an average approach to understanding potential acoustic field effects. The proposed method can detect “something is present” but cannot specify whether it is PVC, drugs, or something else.

This study has some limitations, the main one being its use of an idealised simple 2D model. The 2D formulation serves primarily as a proof-of-concept and a computationally efficient framework for exploring the underlying physical mechanisms and the practicality of the proposed detection strategy. While it effectively captures the essential low-frequency impedance-based scattering behaviour, we recognise that fully three-dimensional effects like finite-length scattering out-of-plane diffraction and edge phenomena are not accounted for. Future research could extend this framework to 3D models and real-time inverse reconstruction algorithms. This would significantly enhance the effectiveness and practicality of acoustic detection systems in real-world scenarios, paving the way for further research. From the perspective of real cabin walls, frequency-dependent absorption is common. Different materials dampen low and high frequencies differently. A single absorption coefficient may underestimate or overestimate damping in certain frequency bands, so further research is needed to clarify this.