Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Considering Thrust Ripple Suppression

Abstract

1. Introduction

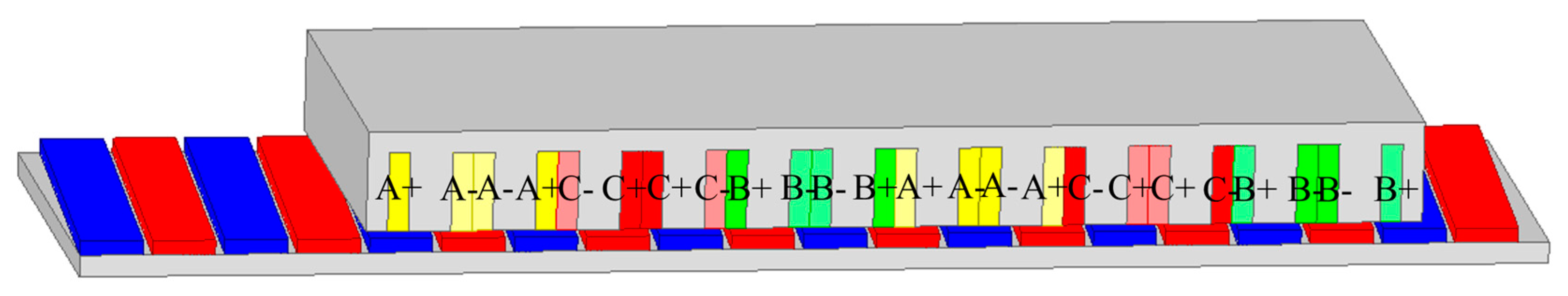

2. Thrust Ripple Analysis of PMSLM

2.1. End Force Analysis

2.2. Cogging Force Analysis

2.3. Winding Asymmetry Force Analysis

3. Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of PMSLM

3.1. Layered Multi-Objective Optimization Principle Analysis

3.1.1. Objective Function

3.1.2. Optimization Variable

3.1.3. Constraint Condition

3.1.4. Mechanism of Layered Multi-Objective Optimization Method

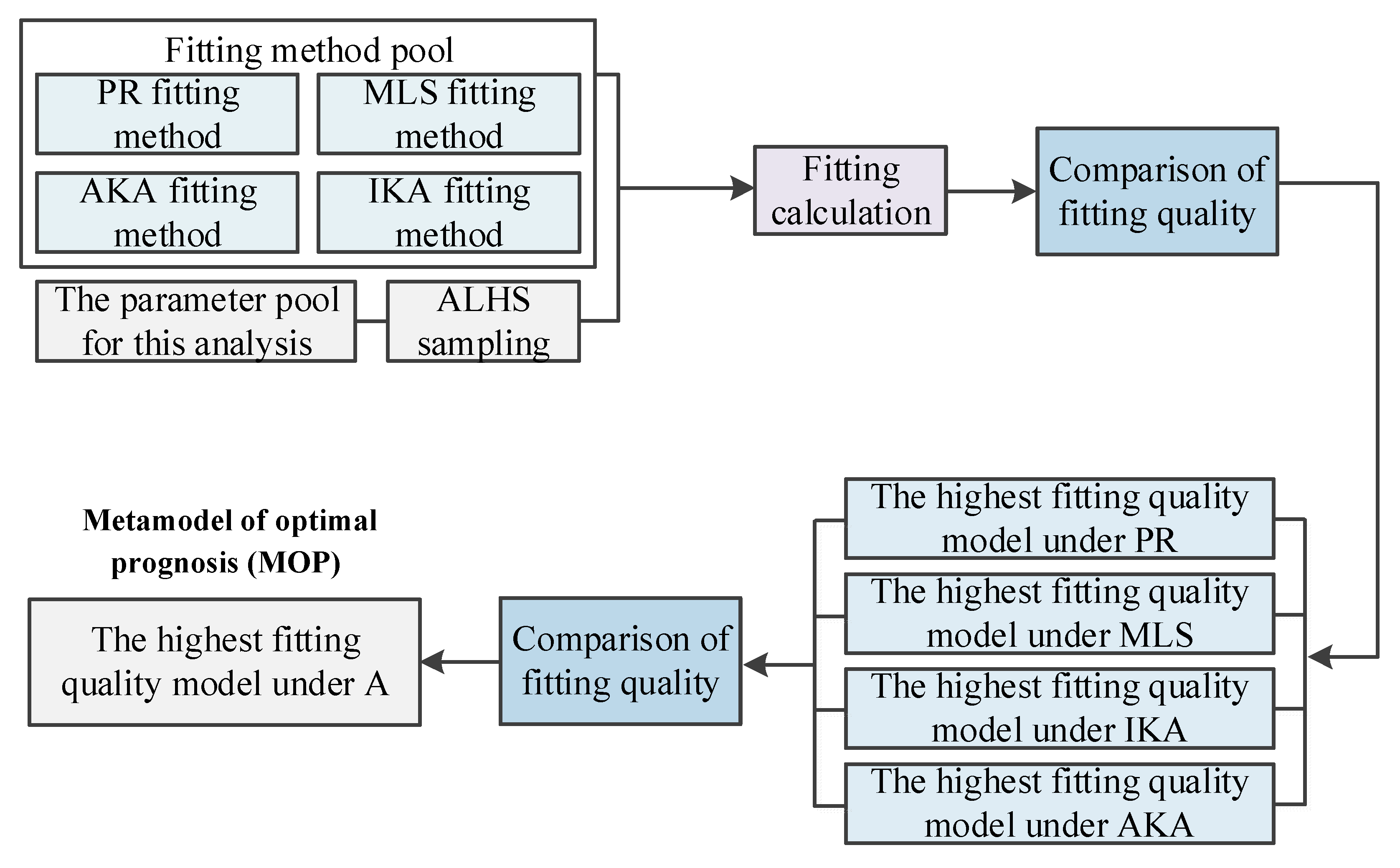

3.2. The First Layer Optimization Considering Sensitivity

3.2.1. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

3.2.2. Establishment of the MOPs

3.2.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Based on PSO

3.3. The Second Layer Optimization Based on MOPs

3.4. The Third Layer Optimization Based on Multi-Objective Taguchi Method

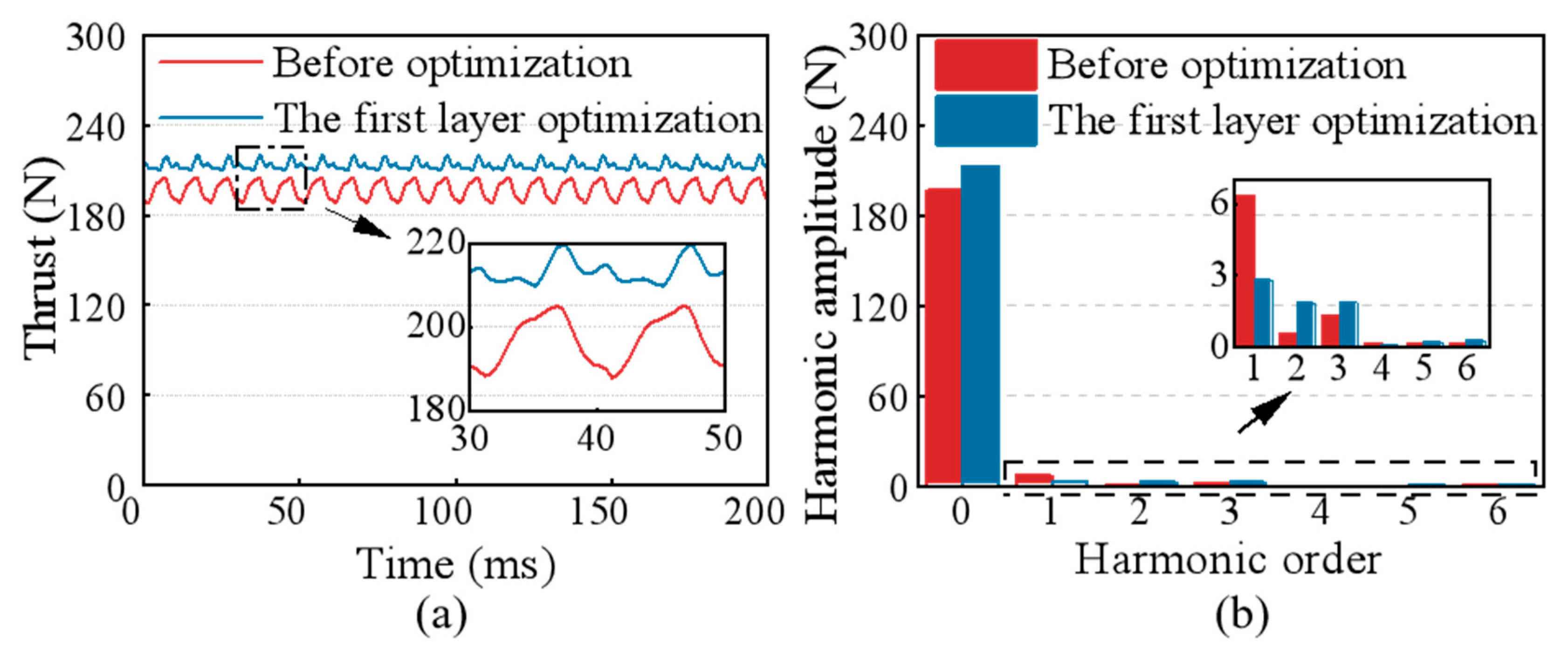

4. Performance Analysis of Optimization Design

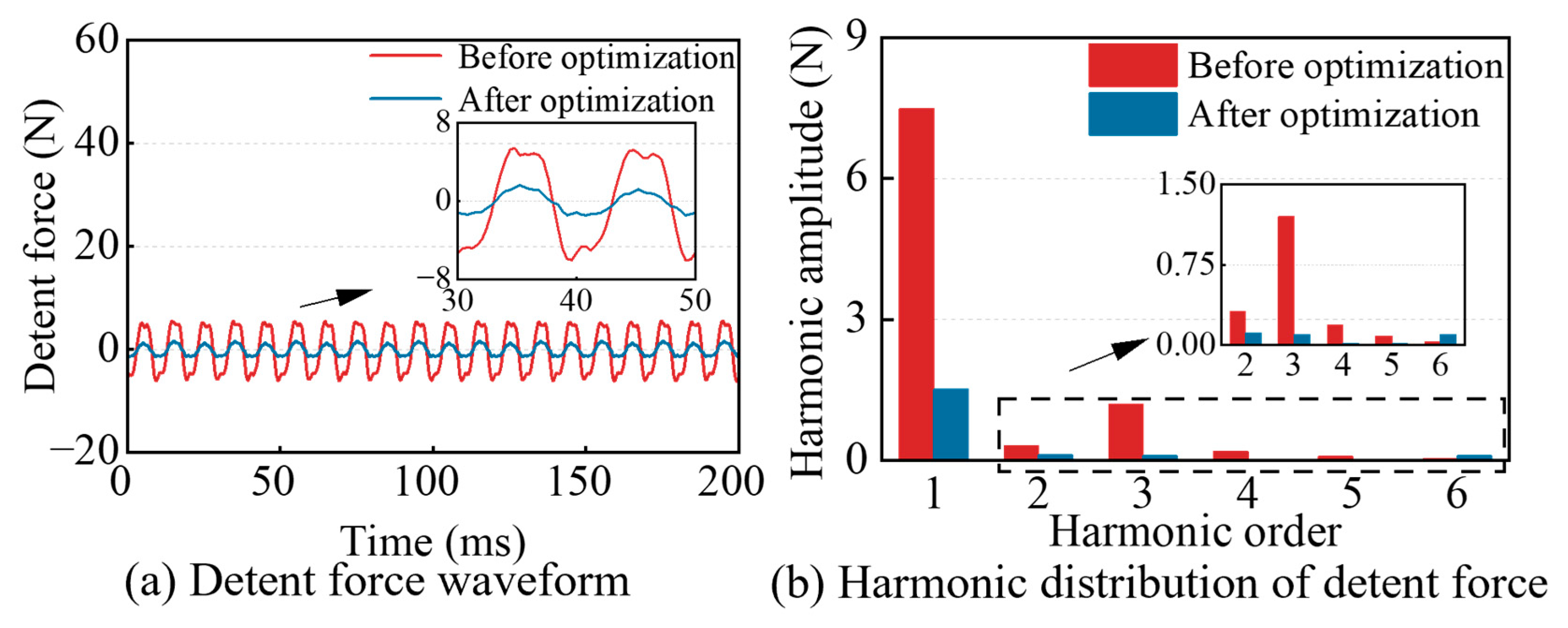

4.1. No-Load Performance

4.1.1. No-Load EMF

4.1.2. Detent Force

4.2. Load Performance

5. Experimental Verification

5.1. Prototype Motor and Experimental Platform

5.2. No-Load Experiment

5.3. Load Experiment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Konuhova, M. Induction motor dynamics regimes: A comprehensive study of mathematical models and validation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.; Sakkas, G.; Xintaropoulos, F.; Pechlivanidou, M.; Kefalas, T.; Tsili, M.; Kladas, A. Overview on permanent magnet motor trends and developments. Energies 2024, 17, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghina, I.; Bizon, N.; Iana, G.; Vasilică, B. Recent advances in fault detection and analysis of synchronous motors: A review. Machines 2025, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Dong, F.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Song, J.; Song, X. Thrust Ripple Reduction in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Based on Electromagnetic Damping-Spring System. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2018, 33, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Robust Design Optimization of a High-Temperature Superconducting Linear Synchronous Motor Based on Taguchi Method. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yu, H.; Guo, B. Analysis of a Tubular Linear Permanent Magnet Oscillator With Auxiliary Teeth Configuration for Energy Conversion System. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2020, 6, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. No-Load Magnetic Field and Cogging Force Calculation in Linear Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Machines with Semiclosed Slots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 5564–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Lu, Q.; Mei, W.; Li, Y. Improved Analytical Modeling of a Novel Ironless Linear Synchronous Machine with Asymmetrical Double-Layer Winding Topology. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisse, K.M.; Nasr, A.; Chareyron, B.; Abdelli, A.; Milosavljevic, M. Surrogate model-based optimization methodology for high torque and power density permanent magnet assisted synchronous reluctance motor. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), Valencia, Spain, 5–8 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Li, Q.; Fan, T.; Wen, X.; Li, Y. Multi-objective optimization design of external rotor permanent magnet machine for in-wheel applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 24th International Conference on the Computation of Electromagnetic Fields (COMPUMAG), Kyoto, Japan, 22–26 May 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Hu, C.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Huang, S. An Online Data-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization of a Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanien, H.M. Particle swarm design optimization of transverse flux linear motor for weight reduction and improvement of thrust force. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 4048–4056. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, G.; Xu, W.; Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Shao, K. Multilevel design optimization of a FSPMM drive system by using sequential subspace optimization method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, T.; Wang, H. Optimal designing of permanent magnet cavity to reduce iron loss of interior permanent magnet machine. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Zuo, Y.; Lee, C.H.T.; Kirtley, J.L. Modeling and optimizing method for axial flux induction motor of electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 12822–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Wang, T.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. System-level design optimization method for electrical drive systems—Robust approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 4702–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, W.; Quan, L.; Xiang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Xue, G. Multiharmonic-layered design and optimization of a flux-concentrated PM vernier motor considering harmonic sensitivity. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Optimization for the pole structure of slot-less tubular permanent magnet synchronous linear motor and segmented detent force compensation. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zheng, S.; Quan, L. Robust-Oriented Optimization Design for Permanent Magnet Motors Considering Parameter Fluctuation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Fan, D.; Xiang, Z.; Quan, L.; Hua, W.; Cheng, M. Systematic multi-level optimization design and dynamic control of less-rare-earth hybrid permanent magnet motor for all-climatic electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Lei, G.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C. Application-oriented robust design optimization method for batch production of permanent-magnet motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 1728–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shi, Z.; Lei, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Multi-objective design optimization of an IPMSM based on multilevel strategy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Quan, L.; Du, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fan, D. Multilevel design optimization and operation of a brushless double mechanical port flux-switching permanent-magnet motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 6042–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Blaabjerg, F.; Wang, H. An overview of artificial intelligence applications for power electronics. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 4633–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Hua, W.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Surrogate model-based multiobjective optimization of high-speed PM synchronous machine: Construction and comparison. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Chi, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ying, Z. Multi-objective optimization design of single side flat tooth unequal width permanent magnet synchronous linear motor based on layered strategy. J. Nanjing Univ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 47, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, P.; Yuan, Y.; Li, G. Optimized design of micro-joint motors using MPSO with embedded ELM indirect surrogate. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Silva, R.; Lowther, D.A. Application of surrogate models to the multiphysics sizing of permanent magnet synchronous motors. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Symbol |

|---|---|

| Permanent magnet width | τm |

| Permanent magnet height | hm |

| Slot width | ws |

| Slot height | hs |

| End width | we |

| Number of turns in phase A | tA |

| Number of turns in phase B | tB |

| Number of turns in phase C | tC |

| Number of skew pole segments | N |

| Skew pole angle | θ |

| Items | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ws (mm) | 5.3 | 5.55 | 5.8 | 6.05 | 6.3 |

| hs (mm) | 10.5 | 10.75 | 11 | 11.25 | 11.5 |

| hm (mm) | 1.5 | 1.75 | 2 | 2.25 | 2.5 |

| τm (mm) | 8.2 | 8.45 | 8.7 | 9.05 | 9.3 |

| we (mm) | 2.435 | 2.685 | 2.935 | 3.185 | 3.435 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Swarm size | 40 |

| Max iterations | 120 |

| Archive size | 150 |

| Grid divisions | 12 |

| Inertia weight | Adaptive |

| Acceleration coefficients | 2 |

| Items | Initial Value | Optimization Results |

|---|---|---|

| Primary core height (mm) | 14 | 14 |

| Primary core length (mm) | 150 | 145 |

| Tooth width (mm) | 5.87 | 6.37 |

| Slot width (mm) | 5.8 | 5.3 |

| Slot height (mm) | 11 | 11 |

| Air gap (mm) | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary core yoke thickness (mm) | 3 | 3 |

| Secondary core length (mm) | 140/modular | 140/modular |

| Pole pitch of permanent magnet (mm) | 10 | 10 |

| Permanent magnet width (mm) | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Pole height of permanent magnet (mm) | 2 | 2.5 |

| Effective length (mm) | 55 | 55 |

| Experimental Results | Simulation Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMF (V) | EMF Constant (V/m/s) | EMF (V) | EMF Constant (V/m/s) | |

| 70 mm/s | 1.11 | 15.86 | 1.18 | 16.86 |

| 85 mm/s | 1.35 | 15.88 | 1.41 | 16.59 |

| 100 mm/s | 1.56 | 15.60 | 1.67 | 16.70 |

| 115 mm/s | 1.79 | 15.57 | 1.92 | 16.70 |

| Average | / | 15.73 | / | 16.71 |

| Experimental Results | Simulation Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrust (N) | Thrust Constant (N/A) | Thrust (N) | Thrust Constant (N/A) | |

| 0.61 A | 29.78 | 48.82 | 31.32 | 51.19 |

| 0.80 A | 38.87 | 48.59 | 40.56 | 50.70 |

| 1.07 A | 52.97 | 49.50 | 55.15 | 51.54 |

| 1.52 A | 73.90 | 48.62 | 77.31 | 50.86 |

| Average | / | 48.88 | / | 51.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, S.; Du, J.; Zhang, J. Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Considering Thrust Ripple Suppression. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020969

Xu S, Du J, Zhang J. Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Considering Thrust Ripple Suppression. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020969

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Shiqi, Jinhua Du, and Jing Zhang. 2026. "Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Considering Thrust Ripple Suppression" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020969

APA StyleXu, S., Du, J., & Zhang, J. (2026). Layered Multi-Objective Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Considering Thrust Ripple Suppression. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020969